1. Introduction

Rock shelters and caves are protected environments in which clastic sediments can be deposited and where post-depositional erosional processes are generally limited. Therefore, depositional sequences within caves and rock shelters are exceptional archives of information of past and present times and they provide important information for geological, palaeoclimatic and archaeological reconstructions (Bosch & White, Reference Bosch, White, Sasowsky and Mylroie2004; Sasowsky & Mylroie, Reference Sasowsky and Mylroie2004; White, Reference White2007; Martini, Reference Martini2011). In prehistoric times caves and rock shelters were also protected environments in which humans often dwelled. In these cases the data coming from the analysis of clastic sediments could provide important additional information to understand human settlement dynamics, as well as the microclimate environments in which they lived (Brandy & Scott, Reference Brandy and Scott1997; Farrand, Reference Farrand2001; Woodward & Goldberg, Reference Woodward and Goldberg2001; Ghinassi et al. Reference Ghinassi, Colonese, Giuseppe, Govoni, Vetro, Malavasi, Martini, Ricciardi and Sala2009; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Davison, Inglis, Farr, Reynolds, Simpson, el-Rischi and Barker2010; Martini et al. Reference Martini, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Capecchi, Ricci, Scaramucci, Spagnolo, Gambassini and Moroni2018).

Several works have described the features of clastic successions in caves, the active depositional processes in these environments, as well as the information that clastic sediments could provide for archaeologically oriented studies (cf. Farrand, Reference Farrand2001; Woodward & Goldberg, Reference Woodward and Goldberg2001). However, the main part of these studies deals with cave successions in which the contribution of external factors is negligible or limited. With respect to caves, rock shelters are transitional environments in which depositional processes typical of the underground environment can merge with those active in the surrounding landscape (Woodward & Goldberg, Reference Woodward and Goldberg2001). The aim of this study is to contribute to understanding the infilling dynamics of rock shelters, as well as the depositional processes active inside them. For this purpose, a ~5.7 m thick siliciclastic succession exposed at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter has been investigated according to modern facies analysis and ichnology principles.

The Oscurusciuto rock shelter is one of the most important Middle Palaeolithic sites of Southern Italy. Its scientific relevance is mainly connected to the rich and well-preserved Mousterian sequence, allowing the performance of multiple interdisciplinary analyses concerning the lifestyle of late Neanderthals in Southern Europe. Studies performed and still ongoing allow an increasingly complex picture to be drawn of the social and economic structure of Neanderthal groups during Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3) (immediately before their disappearance and their related replacement by Modern Humans). The stratigraphic sequence of the Oscurusciuto rock shelter and the characteristics of recovered findings, indeed, are suitable to apply the time-perspectivism approach (with both high-temporal-resolution and diachronic perspectives; cf. Bailey, Reference Bailey2007). This approach yields significant clues to reconstruct the evolution of technical and economic behaviours, hunting strategies, diet, spatial organization of the campsites and mobility (Boscato et al. Reference Boscato, Gambassini, Ranaldo, Ronchitelli, Conard and Richter2011; Marciani et al. Reference Marciani, Spagnolo, Aureli, Ranaldo, Boscato and Ronchitelli2016, Reference Marciani, Arrighi, Aureli, Spagnolo, Boscato and Ronchitelli2018, Reference Marciani, Spagnolo, Martini, Casagli, Sulpizio, Aureli, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020; Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Boscato, Ranaldo and Ronchitelli2016, Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Toniello, Astudillo, Boschin, Boscato and Ronchitelli2019, Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Martini, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020a; Boscato & Ronchitelli Reference Boscato, Ronchitelli and Radina2017). Moreover, the site can be considered one of the last refugia of Neanderthals in Southern Italy, as the bottom of layer 1 was dated after 45 ka BP (see Marciani et al. Reference Marciani, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Badino, Bortolini, Boscato, Boschin, Crezzini, Delpiano, Falcucci, Figus, Lugli, Oxilia, Romandini, Riel-Salvatore, Negrino, Peresani, Spinapolice, Moroni and Benazzi2019 and references therein for a synthesis on the last Mousterian in Italy). Moreover, the archaeological findings made in the upper part of the succession document that some Neanderthal groups attended the shelter in a time interval in which anatomically modern humans had already replaced other Neanderthals in closely spaced areas of the Italian peninsula (i.e. the southernmost part of the Apulian peninsula) (Benazzi et al. Reference Benazzi, Douka, Fornai, Bauer, Kullmer, Svoboda, Pap, Mallegni, Bayle, Coquerelle, Condemi, Ronchitelli, Harvati and Weber2011; Higham et al. Reference Higham, Douka, Wood, Ramsey, Brock, Basell, Camps, Arrizabalaga, Baena, Barroso-Ruíz, Bergman, Boitard, Boscato, Caparrós, Conard, Draily, Froment, Galván, Gambassini, Garcia-Moreno, Grimaldi, Haesaerts, Holt, Iriarte-Chiapusso, Jelinek, Jordá Pardo, Maíllo-Fernández, Marom, Maroto, Menéndez, Metz, Morin, Moroni, Negrino, Panagopoulou, Peresani, Pirson, de la Rasilla, Riel-Salvatore, Ronchitelli, Santamaria, Semal, Slimak, Soler, Soler, Villaluenga, Pinhas and Jacobi2014; Moroni et al. Reference Moroni, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Aureli, Bailey, Boscato, Boschin, Capecchi, Crezzini, Douka, Marciani, Panetta, Ranaldo, Ricci, Scaramucci, Spagnolo, Benazzi and Gambassini2018; Marciani et al. Reference Marciani, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Badino, Bortolini, Boscato, Boschin, Crezzini, Delpiano, Falcucci, Figus, Lugli, Oxilia, Romandini, Riel-Salvatore, Negrino, Peresani, Spinapolice, Moroni and Benazzi2019).

2. Methods and terminology

The sedimentological/stratigraphic analysis has been carried out with bed-by-bed sedimentological logging and architecture line drawings of the sections exposed due to archaeological excavations. The descriptive sedimentological terminology used is from Harms et al. (Reference Harms, Southard, Spearing and Walker1975, Reference Harms, Southard and Walker1982), Walker & James (Reference Walker, James, Walker and James1992) and Collinson et al. (Reference Collinson, Mountney and Thompson2006).

Sedimentological and stratigraphic analysis have been integrated with the study of the traces of life–substrate interactions (ichnology) (Frey & Pemberton, Reference Frey and Pemberton1985; Bromley, Reference Bromley1996; Seilacher, Reference Seilacher2007; Buatois & Mángano, Reference Buatois and Mángano2011). Ichnology focuses on traces such as burrows, tracks, trails, among other structures (Bromley, Reference Bromley1996). Traces include (1) bioturbational structures, reflecting the disruption of soft sediment (e.g. tracks, trails, burrows); (2) bioerosional structures, reflecting the excavation of hard sediment (e.g. borings, gnawings, scrapings, bitings); (3) biostratification structures, reflecting stratification features imparted by biogenic activity (e.g. biogenic graded bedding, byssal mats, stromatolites); and (4) biodeposition structures, reflecting the biological production or concentration of sediment (biodeposition; e.g. faecal pellets, coprolites, pseudofaeces) (Frey & Pemberton, Reference Frey and Pemberton1985). The analysis was done in vertical sediment exposures, and for this reason the ‘ichnofabric approach’ was preferred because it is efficient in analysing cores and vertical outcrops (Taylor & Goldring, Reference Taylor and Goldring1993; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003; Crippa et al. Reference Crippa, Baucon, Felletti, Raineri and Scarponi2018). The ichnofabric approach is the study of the texture and internal structures of a sediment that result from biological activity at any scale (Martin & Pollard, Reference Martin and Pollard1996; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003; McIlroy, Reference McIlroy2008). In the data presentation and discussion, emphasis has been placed on archaeological layers SU 14-11, due to the relevance of bioturbation in understanding their depositional and post-depositional history.

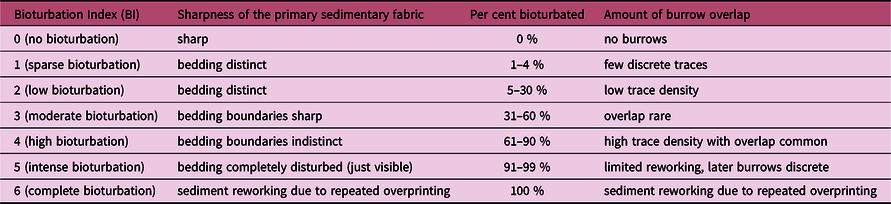

Ichnofabric analysis considers the overall texture of a biologically reworked substrate, being the ichnological equivalent of facies analysis (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003; McIlroy, Reference McIlroy2008). The recorded ichnofabric attributes have been: (i) primary sedimentology; (ii) degree of bioturbation, quantified by the bioturbation index (BI) (Taylor & Goldring, Reference Taylor and Goldring1993); and (iii) components of the ichnofabric. In addition, based on standard ichnological practice (Bromley, Reference Bromley1996; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003; Gingras et al. Reference Gingras, MacEachern and Dashtgard2011), the following ichnological aspects have been observed: relative abundance, burrow size, tiering (vertical distribution of traces; Ausich & Bottjer, Reference Ausich and Bottjer1982; Bottjer & Ausich, Reference Bottjer and Ausich1986; McIlroy, Reference McIlroy and McIlroy2004; Minter et al. Reference Minter, Buatois and Mángano2016), trace frequency, toponomy (position on or within a stratum, or relative to the casting medium; Frey & Pemberton, Reference Frey and Pemberton1985) and distribution.

Table 1. Bioturbation scale used in this study. Modified from Taylor & Goldring (Reference Taylor and Goldring1993), according to which each grade of the bioturbation index is described in terms of the sharpness of the primary sedimentary fabric, burrow abundance and amount of burrow overlap

3. Geologic and geomorphologic settings

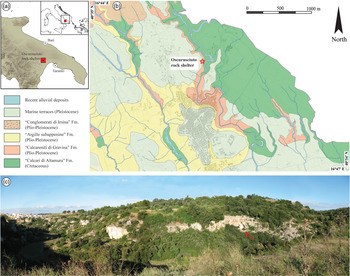

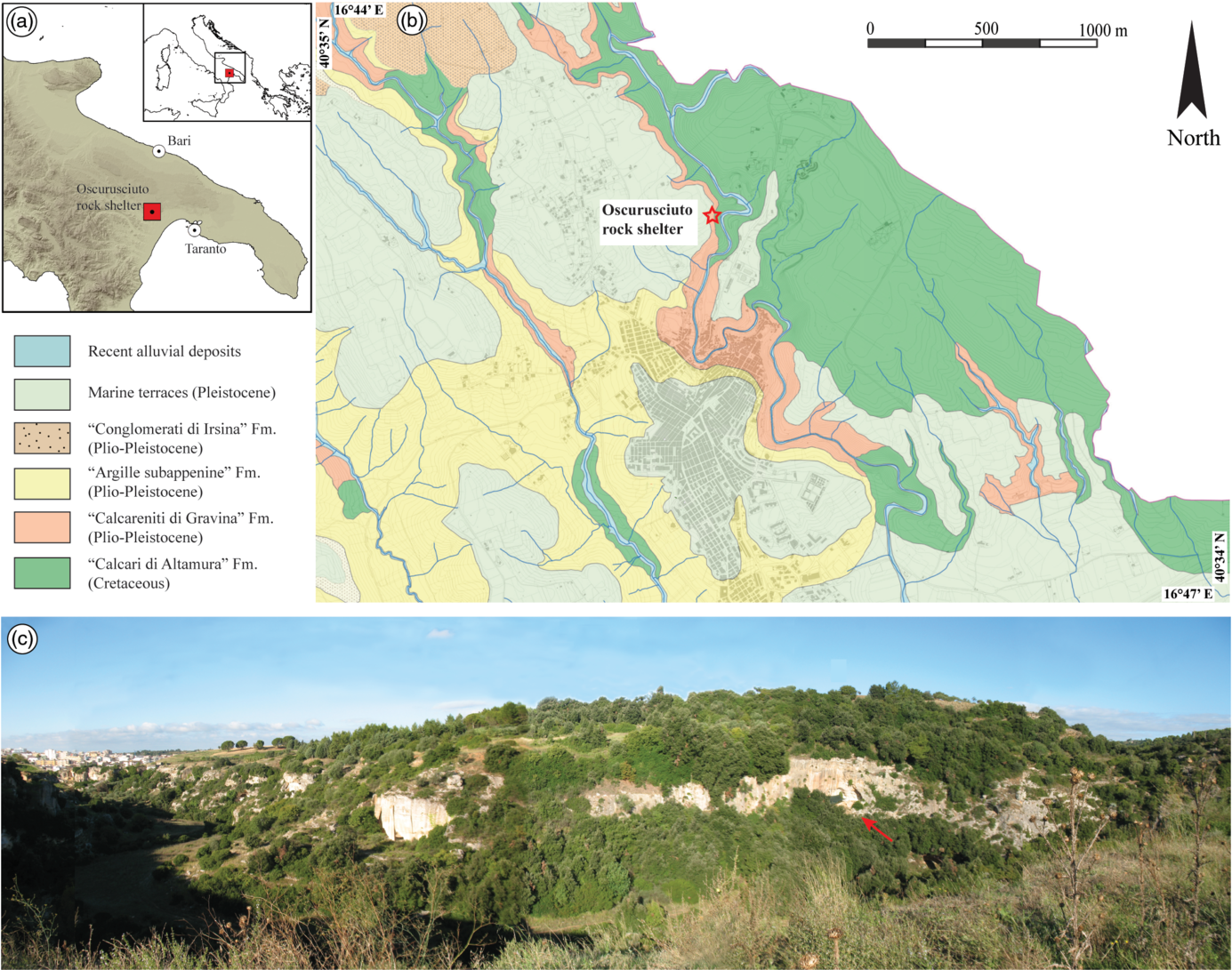

The Oscurusciuto rock shelter is located in the ravine of Ginosa (Apulia, Southern Italy; Fig. 1a, b, c), a narrow ravine incised into Pleistocene calcarenites (Fig. 1c) known in the literature as ‘Calcarenite di Gravina’ (cf. Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Martini, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020a). This formation is also the bedrock of the rock shelter and consists of a bioclastic calcarenite at a place showing a powdery aspect due to the weathering that affected this porous limestone. In this area, the ‘Calcarenite di Gravina’ Fm overlies the ‘Calcari di Altamura’ Fm (Cretaceous limestone) and is in turn overlaid by the ‘Conglomerati di Irsina’ Fm (i.e. Pleistocene conglomerates and sandstones). The origin and geological meaning of this formation is still debated, and the reader is addressed to Sabato et al. (Reference Sabato, Tropeano and Pieri2004) for more information. Reddish soils and siliciclastic Pleistocene sediments interpreted as marine terraces occur in the overall area, covering both calcarenites and siliciclastic formations. The rock shelter is situated ~15 m from the present-day bottom of the ravine and at an elevation of ~235 m a.s.l.

Fig. 1. (a) Location of the investigated site. (b) Simplified geological map of the surroundings of Ginosa village, with the location of the Oscurusciuto rock shelter indicated. (c) Panoramic view of the Ravine of Ginosa, with the location of the Oscurusciuto rock shelter (red arrow) indicated.

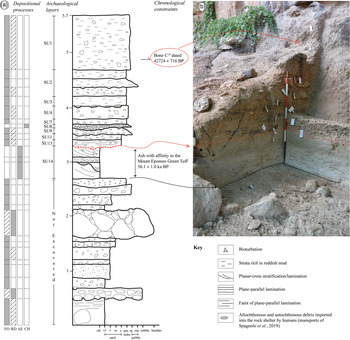

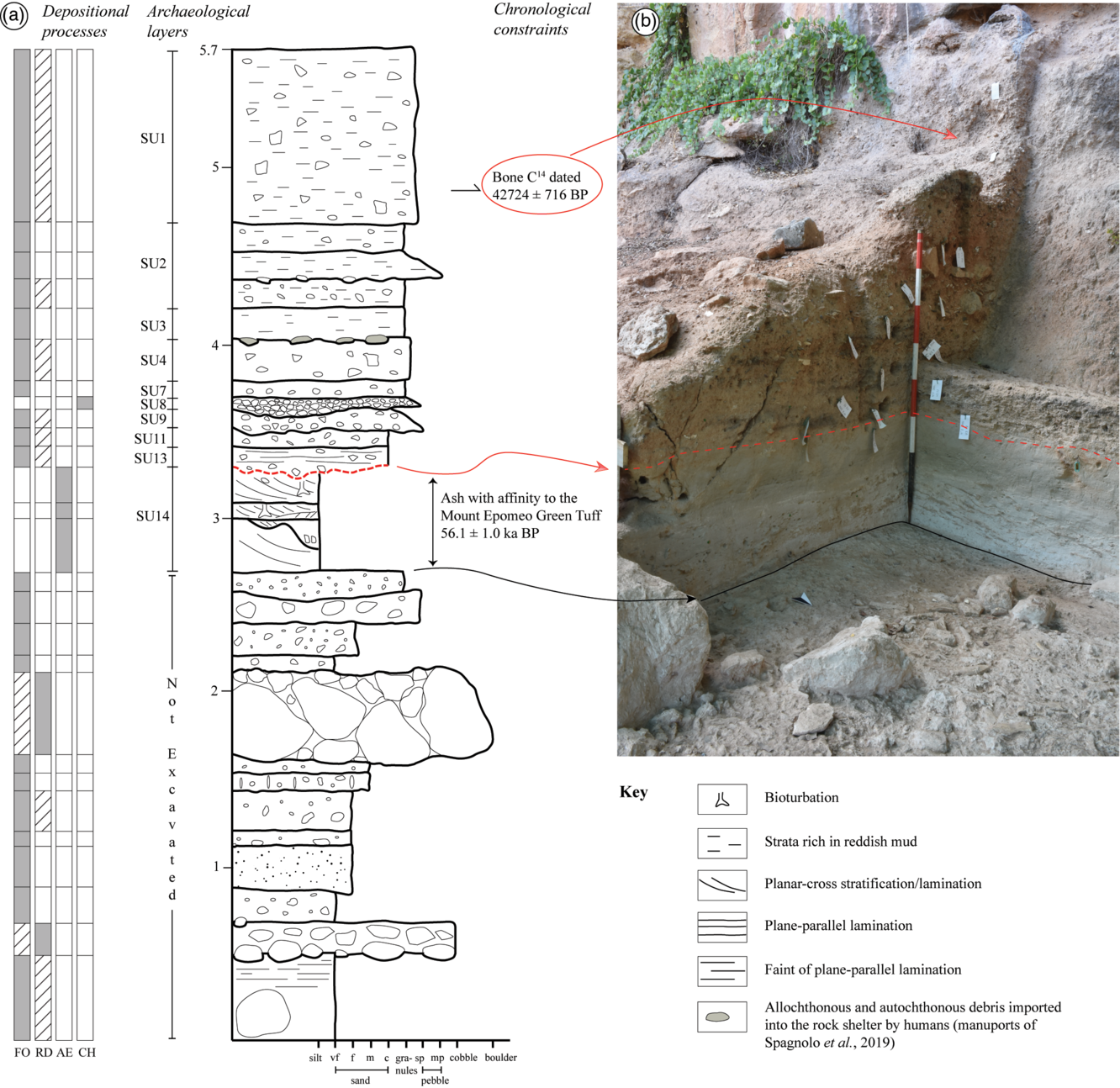

The sedimentary succession is ~5.7 m thick (Fig. 2a, b) and contains Middle Palaeolithic manufacts distributed in several archaeological layers (among which layers 1 to 14 have been extensively excavated; see Fig. 2a) with a sub-horizontal attitude. Archaeological investigations at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter started in 1998 and are still in progress. Currently the first upper 3 m of the sequence have been investigated from an archaeological point of view, while investigation in the lower 3 m will be performed in the future. The sedimentological and stratigraphic analysis present in this study includes the entire succession.

Fig. 2. (a) Sedimentary log of the Oscurusciuto clastic succession, with the depositional processes recognized for each bed, the correlation to archaeological stratigraphy and the available chronological constraints highlighted. (b) View of the upper part of the succession (the part excavated up to now), reporting the main correlation to the sedimentary log.

Two dates are available for the succession: the younger one is a 14C dating from a charred bone coming from the base of the uppermost archaeological layer (SU 1; Fig. 2a, b) and returned a date of 38,500 ± 900 BP (Sample Beta 181165, cal. 42,724 ± 716 BP; cf. Bronk Ramsey & Lee, Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013). The second one is an indirect date derived from the mineralogical and geochemical identification of the tephra layer SU 14 (Fig. 2a), as the Mount Epomeo Green Tuff (dated at ~55,000 years BP) (Marciani et al. Reference Marciani, Spagnolo, Martini, Casagli, Sulpizio, Aureli, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020).

4. Data

4.a. Sedimentary facies

The recognition of sedimentary facies and their depositional processes in archaeological sheltered sites is commonly complicated by the past severe human presence that sometimes deeply altered the original sedimentary features (Karkanas et al. Reference Karkanas, Shahack-Gross, Ayalon, Bar-Matthews, Barkai, Frumkin, Gopher and Stiner2007; Martini et al. Reference Martini, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Capecchi, Ricci, Scaramucci, Spagnolo, Gambassini and Moroni2018). In other cases, the phenomena of human accumulation of archaeological remains (e.g. bones and lithics) and other materials can produce strata not accumulated by natural processes and that do not present evidence of sedimentary structures (i.e. ‘anthropogenic deposits’ sensu Lafferty et al. Reference Lafferty, Quinn and Breen2006).

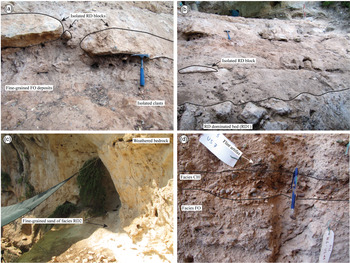

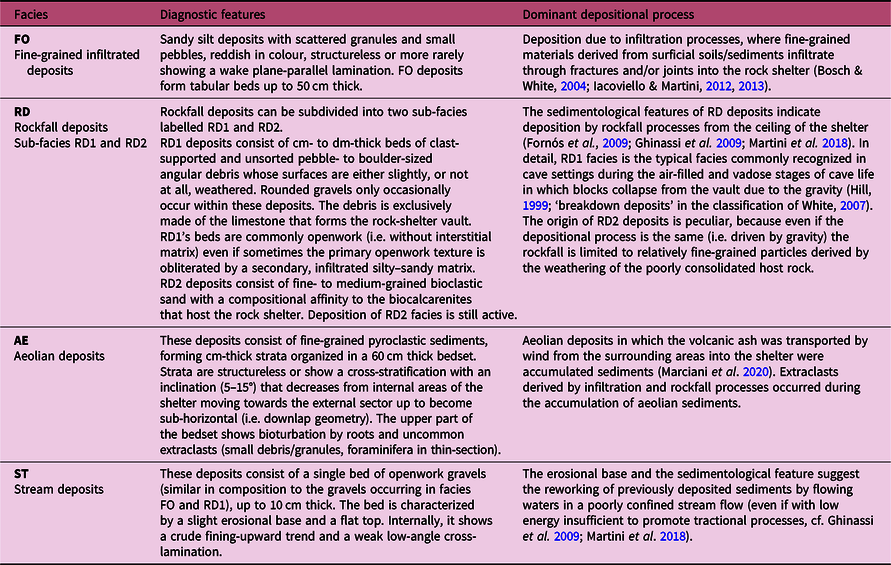

The deposits of the Oscurusciuto rock shelter seem to be free of these complications and four main sedimentary facies have been recognized. Their main diagnostic features are listed in Table 2 and shown in Figures 3 and 4. Two of these facies are characteristic of cave/rock-shelter environments (i.e. FO – fine-grained infiltrated deposits and RD – rockfall deposits; Fig. 3a, b, c), one facies is deposited due to a process typical of the surrounding landscape (i.e. AE – aeolian deposits; Fig. 4), while the other occurs in both environments (ST– stream deposits; Fig. 3d). Stream deposits identified within the Oscurusciuto clastic succession are peculiar: they are made by small gravel and debris similar in size to clasts of underlying and overlying beds, with the difference that ST deposits show an open framework texture (i.e. matrix is absent).

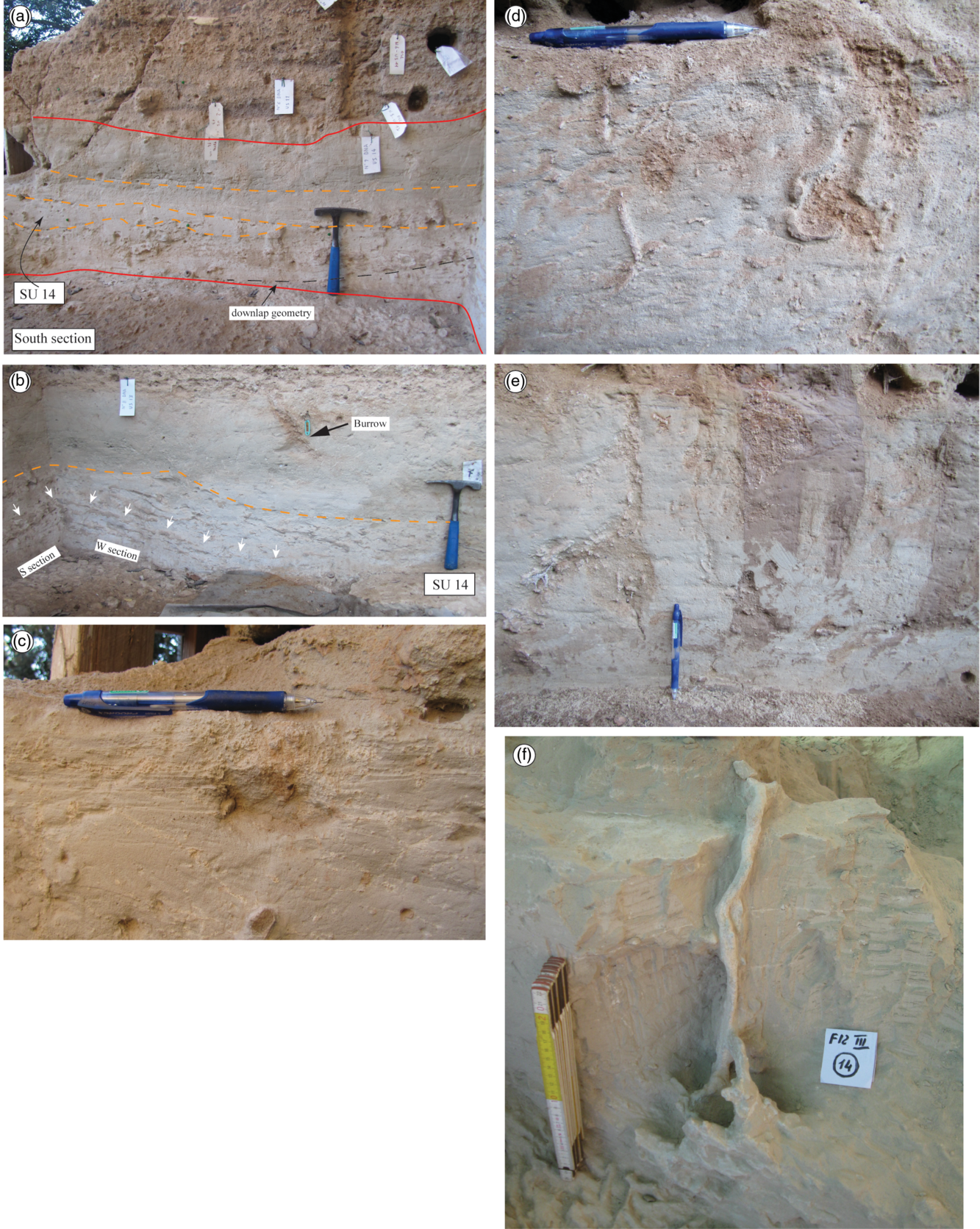

Table 2. Main features of the sedimentary facies recognized at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter

Fig. 3. Sedimentary facies recognized in the Oscurusciuto succession. (a) Fine-grained FO infiltrated deposits (reddish in colour) with occasional rockfall debris and scattered clasts. Hammer for scale is ~28.5 cm long. (b) Bed dominated by rockfall processes (facies RD1) with fine-grained matrix infiltrated by overlying beds, which in turn contain isolated RD blocks. (c) Fine-grained sand that still accumulates in the shelter due to rockfall processes affecting the weathered calcarenites of the host rock. (d) Facies CH deposits interbedded within FO sediments. Note the scarce matrix compared to FO beds. Pencil for scale is ~15 cm long.

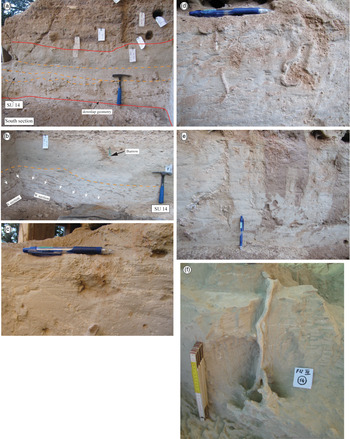

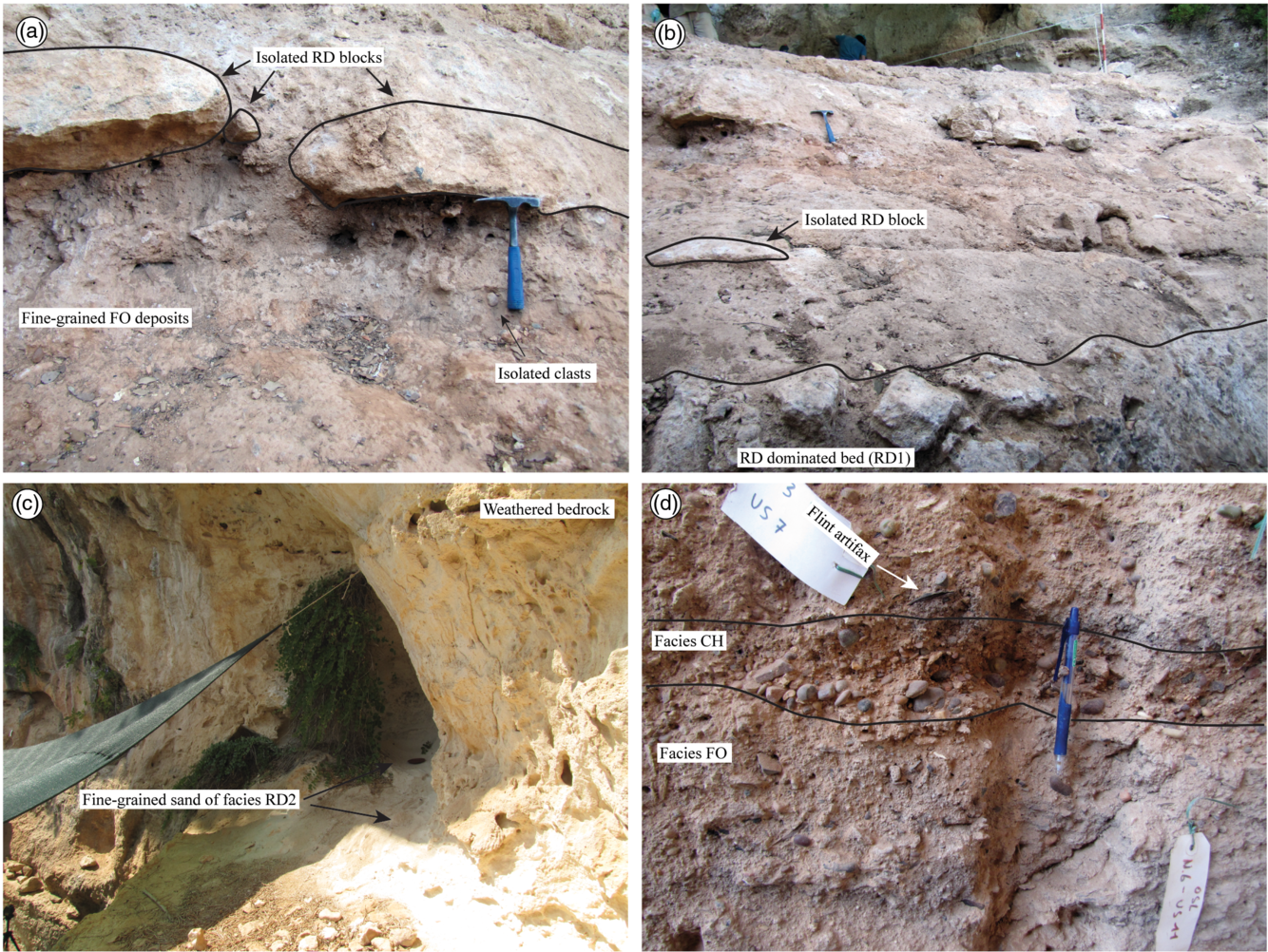

Fig. 4. Aeolian deposits (AE) recognized in the Oscurusciuto succession. (a) View of archaeological bed SU 14 (bounded by solid red lines) with the subtle boundaries of sedimentological beds (dashed orange lines) highlighted. Note the cross-stratification with downlap geometry in the lower bed. Hammer for scale is ~28.5 cm long. (b) Close-up view of the cross-stratification with downlap geometry (highlighted by small white arrows) in the lower bed. Note also a bioturbation in the upper part of the strata (c) Close-up view of plane-parallel lamination occurring at the top of archaeological bed SU 14 (pencil for scale is ~15 cm long). (d, e) Close-up view of bioturbation that mainly occurs in the upper part of archaeological bed SU 14. (f) Close-up view of a rhizolites trace (‘vertical branched trace S’).

The features of rockfall deposits occurring in the shelter are interesting and these deposits can be subdivided into two sub-facies (RD1 and RD2). RD1 consists of clast-supported and unsorted pebble- to boulder-sized angular debris (Fig. 3a, b) whose surfaces are either slightly, or not at all, weathered. The debris are exclusively made of the calcarenite that forms the rock shelter vault. RD1 deposits are the typical facies recognized in caves and originated by blocks collapsing from the vault (Hill, Reference Hill1999; ‘breakdown deposits’ in the classification of White, Reference White2007). RD2 deposits consist of fine- to medium-grained bioclastic sand with a compositional affinity to the biocalcarenites of the host rock (Fig. 3c). The deposition of RD2 deposits is still active: at the end of any archaeological excavation (occurring annually) the site is covered with a protective sheet over which a thin layer of RD2 deposits accumulates during the rest of the year. Deposition of RD2 deposits is driven by gravity similar to RD1 but it is limited to relatively fine-grained particles derived by the weathering of the poorly consolidated host rock.

4.b. Stratigraphy

The stratigraphic sequence exposed at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter is ~5.7 m thick and the whole sequence contains Mousterian artefacts (Fig. 2a, b). The two available chronostratigraphic constraints indicate that the ~1.4 m of sediments deposited between the constraints deposited in a timespan of ~14 ka, thus indicating an average deposition rate of 1 mm a−1. Obviously, this rate does not consider breaks in deposition and erosional events.

Archaeological layer SU 14 (aeolian sediments of facies AE; Figs. 2a, b and 4) allows subdivision of the sequence into two parts. The lower one is dominated by facies settled by infiltration processes (facies FO) that commonly contain debris and rock fragments emplaced due to rockfall processes. Beds dominated by rockfall debris (facies RD) occur and they also show large blocks up to 1 m derived from the collapse of part of the ceiling of the shelter. By contrast, the upper part of the sequence generally lacks beds dominated by rockfall processes. Some large debris have been found during excavation in archaeological layer SU 4 (Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Toniello, Astudillo, Boschin, Boscato and Ronchitelli2019), but some of these show an allochtonous composition (limestone) not related to the ceiling of the cave (calcarenite) even if blocks of calcarenite occur. Consequently, the emplacement of such debris is not compatible with rockfall processes, suggesting that these may have been brought into the shelter by humans (i.e. manuoports; cf. Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Toniello, Astudillo, Boschin, Boscato and Ronchitelli2019). In this scenario, considering also the similar shape and size of limestone and calcarenite debris, it cannot be excluded that the calcarenite debris on layer SU 4 could also be transported into the shelter by humans instead of by classical rockfall processes. Debris surely derived by rockfall processes in the upper part of the succession occurs in deposits of facies FO, but is generally less common and smaller in size than that observable in the lower part of the succession.

4.c. Ichnology

The Oscurusciuto succession contains a diverse association of traces of life–substrate interaction, including bioturbation, bioerosion and biodeposition traces. Open nomenclature has been used to name trace morphotypes (Table 3) based on the practice followed in previous works (Baucon & Felletti, Reference Baucon and Felletti2013a, b). A more specific ichnotaxonomic attribution is precluded by the vertical nature of the exposures, according to which traces are observed in cross-section only. For the same reason, we applied ichnofabric analysis, that is the study of the texture and internal structures of a sediment that result from bioturbation and bioerosion at any scale (Martin & Pollard, Reference Martin and Pollard1996; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003; McIlroy, Reference McIlroy2008). At the study site, two ichnofabric classes have been recognized based on the degree of bioturbation, bioturbation distribution and trace morphology:

-

1. The vertical traces (VT) ichnofabric consists of branched and unbranched tunnels disturbing planar-cross and plane-parallel laminated aeolian deposits (facies AE; Fig. 4d, e, f). Ichnofabric-forming traces comprise four morphotypes (Table 3), which are predominantly passively filled and present a millimetric carbonate lining. Galleries initiate at lithological interfaces, e.g. ichnofabric VT is documented from layer SU 14 at the boundary with the overlying unbioturbated layer SU 13.

-

2. The laminated (LA) ichnofabric consists of plane-parallel deposits (facies FO) with no macroscopic evidence of bioturbation. Microscopic bioturbation structures have been described by Spagnolo et al. (Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Boscato, Ranaldo and Ronchitelli2016). Ichnofabric LA is documented from layer SU 13.

-

3. The bored (BO) ichnofabric is associated to facies FO and consists of Neanderthal-produced bioerosional traces (i.e. butchering marks) on bone. Ichnofabric BO occurs in all layers where in-depth taphonomy was carried out on faunal remains (i.e. SU 4, 5, 6, 7 and 11). It is worth noting that no bioerosional traces due to carnivore activities (gnawing marks on bone surfaces and digested bone specimens) have been detected so far (Boscato & Crezzini, Reference Boscato, Crezzini, De Grossi Mazzorin, Saccà and Tozzi2012; Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Martini, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020a).

Table 3. Ichnofabric-forming traces of the Oscurusciuto site. Open nomenclature has been used to name traces. The abbreviations S and L refer to the size of the structures, ‘small’ and ‘large’, respectively

5. Discussion

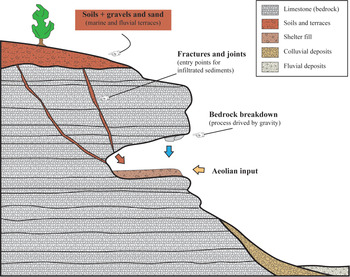

5.a. Facies in rock shelters: dominant and subordinated depositional processes

In siliciclastic successions, each bed/stratum can typically be attributed to a well-defined depositional process. This is not the case of the succession exposed at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter, where the main part of recognized beds derives from a combination of different depositional processes, of which one is dominant and one or more are subordinates (Fig. 2a). For example, beds of facies RD1 emplaced due to rockfall processes but the reddish and fine-grained interstitial matrix is surely derived by infiltration processes (Fig. 3a, b). Likewise, beds originated by infiltration processes (facies FO) commonly contain isolated rockfall debris (Fig. 3a). Only the bed of facies ST (stream deposits; Fig. 3d) and the strata of facies AE (aeolian deposits; Fig. 4) can be considered as deposited by a well-defined depositional process. However, the case of stream deposits (ST) is peculiar because these sediments show a great affinity in terms of clast-size and sorting with underlying and overlying beds (Fig. 3d) and they also show a marked decrease in intraclast matrix. This suggests that the localized flowing waters did not have enough energy to transport large clasts but had sufficient to remove fine particles such as those of intraclast matrix, as can be expected in a shelter environment in which the availability of running water is less than in caves and in the surrounding landscape. As a consequence, it appears realistic to think that flowing waters into the shelter reworked sediments previously deposited by other processes (FO and RD1 deposits).

Indeed, only some beds of facies AE (i.e. the stratigraphic lower) do not show evidence of mixing processes, while as reported by Marciani et al. (Reference Marciani, Spagnolo, Martini, Casagli, Sulpizio, Aureli, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020) the upper few centimetres of these deposits contains occasional siliciclastic clasts derived by infiltration processes, as well as foraminifera fragments observable in thin-sections whose origin is related to rockfall of weathered materials from the ceiling of the shelter.

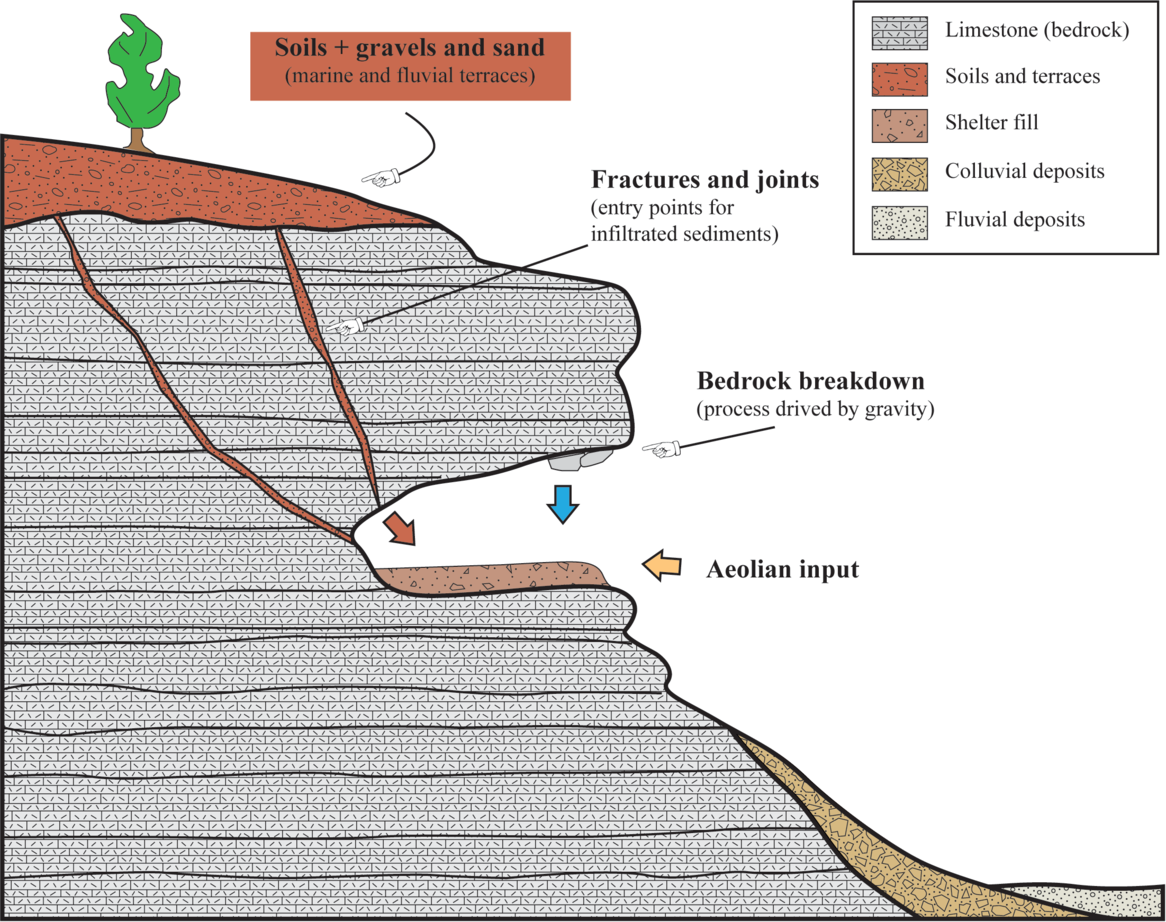

This evidence suggests that what we see in a rock shelter’s facies is not the expression of a single depositional process, but the result of mixed processes in which one of these can be considered dominant according to the observable sedimentary features (see Fig. 5). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that aeolian sediments occur only in the middle of the successions and are composed exclusively of volcanoclastic ash. This indicates that winds are able to accumulate sediments within the shelter only when there is extremely high availability of fine-grained sediments, i.e. immediately after the fallout connected with the Mount Epomeo volcanic event. As a consequence, the efforts of aeolian depositional processes are negligible during ‘normal conditions’, maybe due to lack of fine-grained materials easily transportable by winds or due to the low energetic setting of winds in this geographic area. In this regard also the orographic background of the site plays a fundamental role because the rock shelter opens on the right wall of the ravine (N–S oriented in this sector), implying that the site is protected from winds except for those coming from NE–E–SE quadrants.

5.b. Ichnofabric analysis

The studied ichnofabrics show a marked correlation with sedimentary facies and stratigraphy. Specifically, ichnofabric VT occurs in layer SU 14 and facies AE (Fig. 4d, e, f); ichnofabric LA occurs in layer SU 13 and facies FO; ichnofabric BO occurs in layer SU 11 and facies FO. This correlation suggests that ichnofabrics reflect a time-dependent ecological succession in the context of changing environmental and depositional conditions. This subsection aims to decipher these conditions based on the characteristics of each ichnofabric.

5.b.1. Interpretation of the vertical traces (VT) ichnofabric

The most evident features of ichnofabric VT are (1) simple tiering structure, (2) moderate–low bioturbation intensity and (3) a peculiar toponomy of its traces, that is, tunnels are found close to the boundary with the stratigraphically overlying ichnofabric (Fig. 4d, e, f). For instance, numerous tunnels penetrate layer SU 14 from the boundary with the overlying layer SU 13, which is virtually unbioturbated. On the whole, these features are interpreted to reflect the activity of a single community that opportunistically colonized a stressful environment after a break in sedimentation. In fact, incomplete bioturbation indicates that some stress factor prevented total reworking of the substrate (Bromley, Reference Bromley1996; Buatois & Mángano, Reference Buatois and Mángano2011; Gingras et al. Reference Gingras, MacEachern and Dashtgard2011; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018). Among the suite of possible stress factors for bioturbators (cf. Gingras et al. Reference Gingras, MacEachern and Dashtgard2011; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018), the high deposition rates recorded by aeolian sediments of bed SU 14 seem the most likely to explain such a situation.

This interpretation is supported by toponomy, which is incompatible with a composite ichnofabric, i.e. an ichnofabric formed by either the upward replacement of successive communities or the upward movement of a single tiered community (Buatois & Mángano, Reference Buatois and Mángano2011; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018). Rather, traces of ichnofabric VT are found only near the boundary with overlying layers. As such it is a simple ichnofabric, i.e. it reflects the activity of a single community at a single time (Buatois & Mángano, Reference Buatois and Mángano2011; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018). This implies a short colonization window, that is the period of time which is available for successful colonization of the substrate (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003).

This also indicates the post-depositional nature of the colonization, i.e. traces of ichnofabric VT have been emplaced after the deposition of the sediment in which they are preserved. Simple ichnofabrics are often the result of colonization events by opportunistic organisms (Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018). Paraphrasing the words of Taylor et al. (Reference Taylor, Goldring and Gowland2003), ichnofabric VT represents a ‘one-off’ colonization. Accordingly, ichnofabric VT resulted from the rapid colonization of a vacant ecological niche that opened after a short break in sedimentation.

Another prominent feature of ichnofabric VT is the virtually identical sediment with which traces are passively filled (Fig. 4d, e, f). Passive filling of a tunnel requires an opening through which the filling sediment can pass. Hence, the tunnels were open structures at the depositional interface. The fact that each tunnel is filled by the same sediment implies that the filling event was geologically instantaneous.

Most traces also present the same type of carbonate lining (Fig. 4d, f). Lining is typically interpreted as a product of tracemaking activities (for example, in marine settings many crustaceans line their burrows to cope with shifting substrates; cf. Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Ronchi, Felletti and Neto de Carvalho2014). However, most traces of the ichnofabric VT display the same kind of lining even if they are morphologically different from each other. This suggests that lining is not exclusively related to the tracemaking activities, but that it is somehow related to physico-chemical processes that acted within the Oscurusciuto rock shelter. In continental environments, precipitation of carbonate is common around roots because exuded organic acids aid in the acquisition of mineral nutrients, favouring root calcification (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Xue, Zamanian, Colin, Duchamp-Alphonse and Pei2019). If the tunnels of ichnofabric VT are all related to ancient roots, this process may explain the carbonate lining. Such an explanation holds well for the morphotype ‘vertical branched trace S’, which is characterized by branches of variable width (see Table 3). Variable width is a typical feature of root traces (Klappa, Reference Klappa1980). Alternatively, it is well known that deposition of CaCO3 onto natural surfaces can derive from thin films of supersaturated solutions occurring in natural waters (Dreybrodt, Reference Dreybrodt1980). It is therefore plausible that a thin film of supersaturated fluid may have deposited carbonates onto the surface of an animal burrow. Post-depositional carbonate precipitation has been indicated as a key factor in the preservation of invertebrate burrows in cave settings (Frank, Reference Frank, Mulvaney and Golson1968). Further studies on the taphonomy of continental traces are required to understand the origin of the lining of ichnofabric VT.

Deciphering the identity of the tracemaker is a challenging task because the ichnofabric VT traces display features shared between animal and plant traces. The presence of a passive fill is apparently more consistent with open burrows produced by animals, rather than traces produced by roots (rhizolites). However, it should be noted that rhizoliths can be preserved as root tubules, which are cemented cylinders around root moulds (Klappa, Reference Klappa1980). Carbonate lining, which is observed in ichnofabric VT traces, is commonly documented from rhizolites. Carbonate lining can derive from precipitation processes around roots, favoured by exuded organic acids aiding the acquisition of mineral nutrients in living roots (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Xue, Zamanian, Colin, Duchamp-Alphonse and Pei2019). Root traces are usually (but not exclusively) characterized by an irregular diameter and tapering (Klappa, Reference Klappa1980). Except for the ‘vertical branched trace S’ (Fig. 4f), these features are not observed in the traces of ichnofabric VT, possibly suggesting an animal origin. A rock shelter such as the Oscurusciuto site may appear an unsuitable environment for burrowing animals, but it should be noted that many infaunal animals inhabit cave and cave-like environments. To cite just some examples, many troglobitic amphipods (i.e. obligatory cavernicoles) are burrowing (Holsinger & Dickson, Reference Holsinger and Dickson1977); different spider species burrow inside or in the close vicinity of caves (Sedgwick & Schwendinger, Reference Sedgwick and Schwendinger1990; Rasalan et al. Reference Rasalan, Barrion-Dupo, Bicaldo and Sotto2015); burrowing rodents have been observed in the Oscurusciuto shelter during the development of this study. Nevertheless, it is challenging to compare modern burrows with the traces of ichnofabric VT because there is a lack of neoichnological studies in cave environments. In addition, the traces of ichnofabric VT mainly occur as 2D cross-sections, hence it is difficult to understand their 3D shape.

5.b.2. Interpretation of the laminated (LA) ichnofabric

Ichnofabric LA is characterized by the absence of distinct macroscopic burrows and the preservation of lamination. Complete absence of macroscopic bioturbation is here interpreted as the lack of burrowing activity, although taphonomical processes can also obliterate traces (Bromley, Reference Bromley1996; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018). As such, ichnofabric LA reflects a stressful environment that prevented colonization of the substrate. The presence of microscopic bioturbation structures, which are described by Spagnolo et al. (Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Boscato, Ranaldo and Ronchitelli2016), supports this interpretation. In fact, small burrow sizes are usually a proxy for stressful conditions (Gingras et al. Reference Gingras, MacEachern and Dashtgard2011).

5.b.3. Interpretation of the bored (BO) ichnofabric

Ichnofabric BO comprises distinct bioerosional and bioturbational structures. However, these trace groups do not represent the activity of a single community. In the context of ichnofabric BO, bioerosional and bioturbational structures represent two different suites of traces, each of which reflects a distinct time of emplacement (Buatois & Mángano, Reference Buatois and Mángano2011). Bioerosional traces reflect hominin activity during Middle Palaeolithic times. It should be noted that ichnofabric BO derives not only from bioerosional processes, but also biostratification ones, i.e. the concentration of modified bones is clearly a product of the Neanderthal activity.

By contrast, bioturbational traces indicate the activity of modern fauna and flora since they are associated with their living tracemakers (rodents and plants). As such, ichnofabric BO is a composite ichnofabric resulting from the succession of different communities, i.e. a Musterian and a modern one.

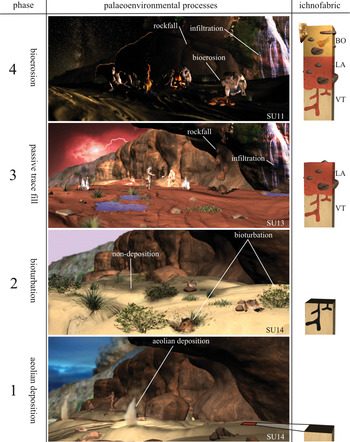

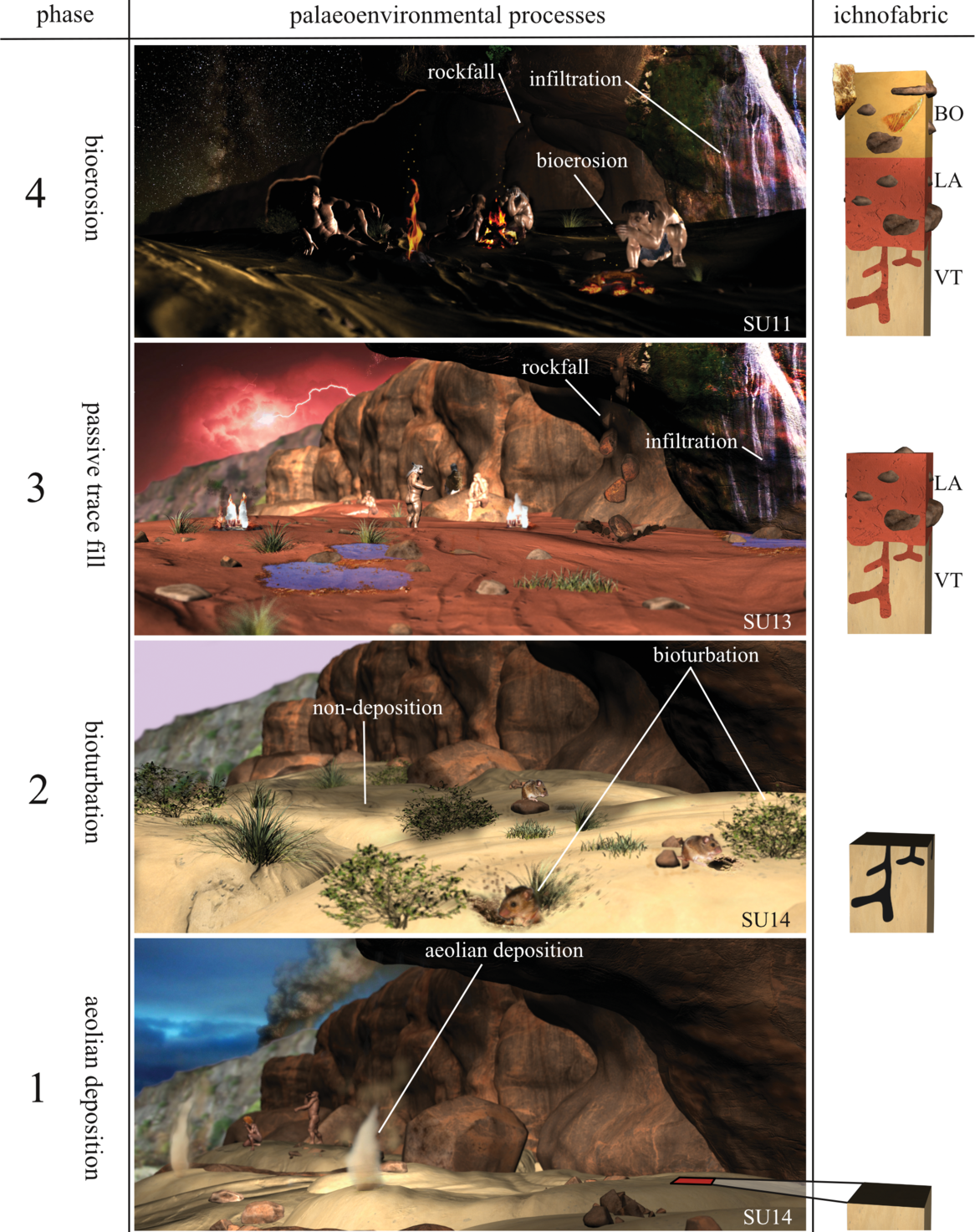

5.c. Bioturbation and preservation of primary structures

Ichnoarchaeology, the application of ichnological methods and themes in archaeology, has been recognized as an important source of information that is often unobtainable using other methods (Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Privitera and Bonacossi2008). Since then, few case studies have explicitly mentioned ichnology as a tool in archaeology (Rodríguez-Tovar et al. Reference Rodríguez-Tovar, Morgado and Lozano2010; Cáceres et al. Reference Cáceres, Muñiz, Rodríguez-Vidal, Vargas and Donaire2014; Hembree, Reference Hembree, Croft, Su and Simpson2018; Neto de Carvalho et al. Reference Neto de Carvalho, Figueiredo, Muniz, Belo, Cunha, Baucon, Cáceres and Rodriguez-Vidal2020). Research on the Oscurusciuto rock shelter supports the idea that the integration of ichnology and sedimentology is important for understanding the palaeoenvironmental evolution of archaeological sites. Specifically, sedimentary structures provide information on the conditions at the time of deposition, and ichnology provides information on the time of non-deposition in which organisms colonize the substrate (McIlroy, Reference McIlroy and McIlroy2004). In fact, the stacking pattern of ichnofabrics and sedimentary structures reveals a four-phase history for the Oscurusciuto shelter (Fig. 6). The first phase consisted of the rapid sedimentation of SU 14. Although SU 14 is bioturbated, its bioturbational traces reflect post-depositional colonization since they have been initiated at the interface with the overlying layers. Therefore, phase 1 is interpreted to represent a phase of high sedimentation rate which prevented infaunal colonization. A significant decrease in sedimentation rate followed phase 1. During this second phase, organisms colonized SU 14, producing several open tunnels. These tunnels have been passively filled in the third phase by the deposition of SU 13. Sedimentary evidence indicates rockfall and infiltration as the major depositional processes of the third phase. The fourth phase reflects the increase in Neanderthal activities (e.g. accumulation of artefacts and modified bones). Sedimentary evidence suggests that infiltration and rockfall were active during this phase. This interpretation exemplifies the fact that ichnofabrics can yield information about the palaeoenvironment during and after the deposition of a bed.

Fig. 5. Synthesis of the main depositional processes active in the Oscurusciuto rock shelter.

Fig. 6. Palaeoenvironmental and ichnological evolution of the Oscurusciuto rock shelter. The square in phase 1 indicates the location of the ideal ichnofabric log. SU refers to the stratigraphic units described in the text. VT stands for vertical traces ichnofabric, LA for laminated ichnofabric, BO for bored ichnofabric.

Structureless strata are characterized by the absence of primary sedimentary structures. In cave and sheltered sites structureless strata are related to three main factors: (i) deposition by mass-transport processes; (ii) human trampling and digging (Karkanas et al. Reference Karkanas, Shahack-Gross, Ayalon, Bar-Matthews, Barkai, Frumkin, Gopher and Stiner2007; Martini et al. Reference Martini, Ronchitelli, Arrighi, Capecchi, Ricci, Scaramucci, Spagnolo, Gambassini and Moroni2018); and (iii) bioturbation due to animals or roots. While mass-transport processes deposited strata that lack structures, the other two factors act after the deposition and lead to the destruction/obliteration of primary structures. Nevertheless, there is a tendency in archaeology to relate the poor preservation of sedimentary structures to human activities. The scarce preservation of sedimentary structures in strata containing abundant artefacts is typically attributed to human trampling and digging and used as an indirect index of human-residing time within the shelter. In this framework, the ichnofabric VT strongly supports that structureless archaeological deposits are not necessarily the result of human trampling, but they can reflect the activity of plant roots and/or burrowing animals.

In studies dealing with archaeological successions in caves and shelters, the role of root bioturbation (rhizoturbation) is often underestimated, mainly because of historical phenomena involving either Life or Earth Sciences. In fact, despite scientists’ long fascination with caves, their plant diversity remains poorly documented (Monro et al. Reference Monro, Bystriakova, Fu, Wen and Wei2018). As a result, the poorly lit environment of caves does not conjure up images of rooted plants. Although rhizolites are clearly recognized as trace fossils, root bioturbation still remains an under-studied field of ichnology (Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Bordy, Brustur, Buatois, De, Duffin, Felletti, Lockley, Lowe, Mayor, Mayoral, Muttoni, Carvalho, De Santos, Seike, Song, Turner, Cunningham, De Duffin, Felletti, Gaillard, Hu, Hu, Jensen, Knaust, Lockley, Lowe, Mayor, Mayoral, Mikuláš, Muttoni, Neto de Carvalho, Pemberton, Pollard, Rindsberg, Santos, Seike, Song, Turner, Uchman, Wang, Yi-Ming, Zhang and Zhang2012). Plant trace fossils offer significant interpretative challenges, while most of the active ichnologists are zoologically trained (Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Martin and Campbell2004; Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Bordy, Brustur, Buatois, De, Duffin, Felletti, Lockley, Lowe, Mayor, Mayoral, Muttoni, Carvalho, De Santos, Seike, Song, Turner, Cunningham, De Duffin, Felletti, Gaillard, Hu, Hu, Jensen, Knaust, Lockley, Lowe, Mayor, Mayoral, Mikuláš, Muttoni, Neto de Carvalho, Pemberton, Pollard, Rindsberg, Santos, Seike, Song, Turner, Uchman, Wang, Yi-Ming, Zhang and Zhang2012).

However, the ecology of modern caves and shelters demonstrates that rooted plants can survive not only at a cave entrance, but also in the twilight zone. For instance, the one leaf plant (Monophyllea) is endemic to the twilight zone of caves in Borneo (Gunn, Reference Gunn2004, p. 748). A diverse angiosperm is reported from SW China caves, one of which is the type locality for eight species of vascular plants (Monro et al. Reference Monro, Bystriakova, Fu, Wen and Wei2018).

Ichnofabric VT, preserved in the SU 14 layer (made exclusively by aeolian sediments, AE) of the Oscurusciuto succession, allows some considerations on the possible role of vegetation in the bioturbation of clastic deposits settled in sheltered sites. Ichnofabric VT includes abundant examples of rhizoliths (‘vertical branched burrows’ in Table 3), showing that plants colonized the shelter sediment after a short aeolian depositional event. In fact, as demonstrated by Marciani et al. (Reference Marciani, Spagnolo, Martini, Casagli, Sulpizio, Aureli, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020), aeolian sediments were accumulated over a short time interval, in the order of days/seasons or at the maximum some years.

Consequently, plants colonized the interior sectors of the Oscurusciuto shelter and contributed significantly to the bioturbation of sediments. The Oscurusciuto case study encourages caution in the interpretation of structureless deposits as they are not necessarily related to human bioturbation as is commonly assumed. In fact, bioturbation tends to obliterate previously emplaced traces (Bromley, Reference Bromley1996), therefore structureless layers can result from intense rhizoturbation coupled with low sedimentation rates. Fast burrowers such as insects and rodents can produce similar results.

Unfortunately, there are no available criteria to distinguish among human and non-human bioturbation in intensely bioturbated deposits. Achieving this challenging task is much needed to avoid overestimation of human impact in archaeological deposits.

However, it is clear that an integrated sedimentological/ichnological approach can significantly improve the recognition of depositional processes and possible syn-/post-depositional disturbances acting in caves and rock shelters. These issues play a decisive role in the wider branch of site taphonomy, the centrality of which is increasingly evident in the pre-/protohistoric archaeology debate (e.g. Lenoble et al. Reference Lenoble, Bertran and Lacrampe2008; Bertran et al. Reference Bertran, Lenoble, Todisco, Desrosiers and Sørensen2012; Spagnolo et al. Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Berna, Boscato, Ranaldo and Ronchitelli2016, Reference Spagnolo, Marciani, Aureli, Martini, Boscato, Boschin and Ronchitelli2020a, b, c; Martínez-Moreno et al. Reference Martínez-Moreno, Mora Tocal, Benito Calvo, Roy Sunyer and Sánchez-Martínez2019).

6. Conclusions

The study of the clastic succession exposed at the Oscurusciuto rock shelter archaeological site allows us to better understand the depositional and post-depositional processes that can typify these peculiar environments. Rock shelter successions record a mixing of depositional processes, some of these typical of caves and underground environments (i.e. infiltration of fine-grained material from fractures and joints, rockfall from the ceiling of the shelter), and others that typify the surrounding landscape (i.e. aeolian processes). Only occasionally are beds deposited by a unique and well-defined process, while commonly their features are attributable to a mixing of different processes in which one is dominant and one or more are subordinated.

While the sedimentological study of the succession can provide information about the environmental settings at the time of deposition, the ichnologic study can provide information concerning the environmental settings during breaks in the sedimentation. Therefore, this multidisciplinary approach can better refine the evolutionary history of siliciclastic succession in rock shelters.

In this regard, aeolian fine-grained sediments (whose origin is related to the Mount Epomeo Green Tuff pyroclastic event) accumulated within the shelter in a short time interval. Despite the short duration of the depositional event, these beds record a marked bioturbation. This indicates a post-depositional colonization by opportunistic communities that lived within the rock shelter during a phase of no or reduced sediment accumulation. This evidence suggests that bioturbation at a sheltered site can be underestimated, with a contemporary overestimation of the responsibility of human trampling and digging for the lack of primary sedimentary structures in these peculiar depositional and human-influenced environments.

The sedimentological and stratigraphic study of rock shelter successions, over their pure scientific geological meaning, can provide helpful information to resolve the most recent archaeological studies in which trying to understand the human settlement dynamics is one of the main issues. In this view, the facies analysis and ichnology analysis, integrated with other approaches (such as, for example, the innovative spatial analysis, micromorphometry of sediments and, more generally, the taphonomic analysis of Palaeolithic contexts from a global perspective), will help not only to estimate the integrity state of the sites, but also to distinguish the human and non-human components, in particular in the structureless layers.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The research projects, still ongoing, began in 1998 and were carried on by the Dipartimento di Scienze Fisiche, della Terra e dell’Ambiente, U.R. Preistoria e Antropologia of the University of Siena (Italy) with the partnership of Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le province di Brindisi, Lecce e Taranto (MIBACT permissions: DDG rep. N° 935, 30.08.2019), the local Section of Legambiente and the Municipality of Ginosa. The authors are grateful to Prof. Annamaria Ronchitelli and Prof. Paolo Boscato (University of Siena) for their great work at the site and for their direction and coordination of excavation and research. The authors are indebted to the Municipality of Ginosa, Mr Piero di Canio (and his family), Onlus CESQ and to all the participants in the excavations. Prof. Mehmet Cihat Alçiçek, an anonymous reviewer and the Editor Prof. Stephen Hubbard are thanked for their constructive comments, which helped to improve the manuscript. The study was funded by the National Geographic Society/Exploration Grant Program (grant NGS-61617R-19 to I Martini).