Introduction

There is surprisingly little research on understanding and improving attitudes to autism. Further, in the limited body of existing research, there are several issues with current understanding of the individual differences underlying attitudes towards autistic people. First, there is inconsistent evidence for and against participants’ age (e.g., Kuzminski et al., Reference Kuzminski, Netto, Wilson, Falkmer, Chamberlain and Falkmer2019), sex (e.g., Cage et al., Reference Cage, Di Monaco and Newell2019), and autism knowledge and autistic traits (e.g., Mac Cárthaigh & López, Reference Mac Cárthaigh and López2020) being related to their attitudes to autism. Second, there have been longstanding concerns with the measurement of autism knowledge and attitudes to autistic people (Hanel & Shah, Reference Hanel and Shah2020; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Harris, Schwartz, Benallie, Golson and Benney2019). Third, there is a paucity of multivariate designs/analyses examining the unique contributions of potential factors to attitudes whilst accounting for others. For example, whilst there is relatively clear evidence for greater contact with autistic people being predictive of more favourable attitudes and prosocial behaviours towards these individuals (e.g., Payne & Wood, Reference Payne and Wood2016), this is not always accounted for when investigating other predictors of attitudes to autism.

Objective

Overall, our examination of this (limited) body of research indicates that it is currently unclear which, if any, of these factors are associated with public attitudes to autism. To help address this gap in the literature—drawing on recent advancements in measuring knowledge of and attitudes towards autism (e.g., McClain et al., Reference McClain, Harris, Schwartz, Benallie, Golson and Benney2019)—we sought to investigate the relative contributions of participant age, sex, autism knowledge, level of contact, and autistic traits to attitudes towards autistic people. Identifying predictors of attitudes towards autistic people is an important step towards understanding and changing potentially negative attitudes.

Methods

Participants formed a convenience sample of 229 individuals (72.93% female, 25.76% male; 1.31% other) recruited using social media platforms, aged 16 to 78 years (M = 28.62, SD = 15.45). No compensation was offered for this study, which was completed online. Participants gave informed consent and all procedures complied with the ethical standards of national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Two participants were excluded as multivariate outliers, with standardised residuals >3SDs from the mean. The pattern of results was unchanged if they were included.

After reporting their age and sex, participants completed up-to-date measures quantifying their autism knowledge (between 0–31; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Harris, Schwartz, Benallie, Golson and Benney2019), level of contact with autistic people (between 1–12; Gardiner & Iarocci, Reference Gardiner and Iarocci2014), autistic traits (between 0–10; Allison et al., Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen2012), and their overall attitude towards autistic people (between 0–100; Hanel & Shah, Reference Hanel and Shah2020). Higher scores represented more autism knowledge, contact with autistic people, autistic traits, and favourable attitudes to autism, respectively. See Supplementary Material for more details about the measures.

Results

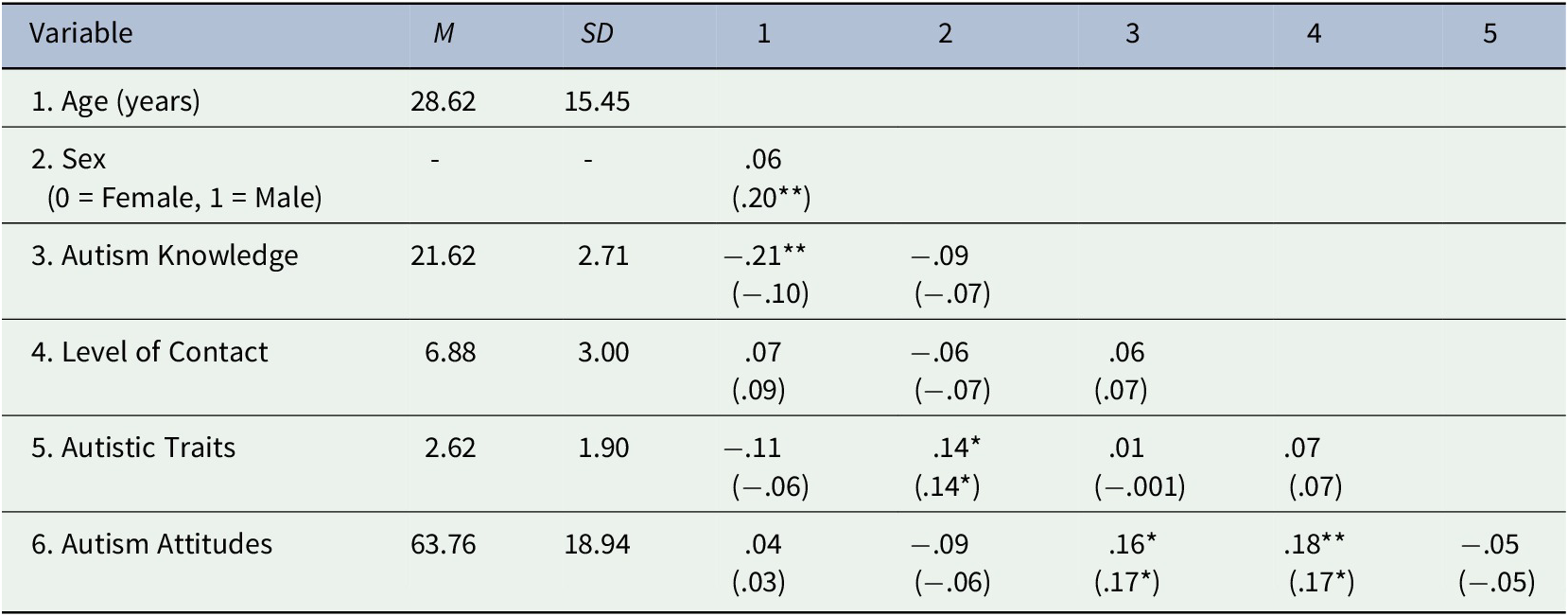

Inspection of the data (Supplementary Material) indicated that, despite expected deviations from a normal distribution (all Shapiro–Wilk p < .05), we had appropriate variance to explore interrelationships between variables (Table 1). Notably, autism knowledge and level of contact were not significantly correlated, yet both variables were positively associated with attitudes towards autistic people.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

Note. Given the distribution of our data, which deviates from a normal distribution, both Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho (in parentheses) are reported for readers with a preference for one type of analysis over the other. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Three participants reporting their sex as ‘other’ are not included in analyses involving this variable.

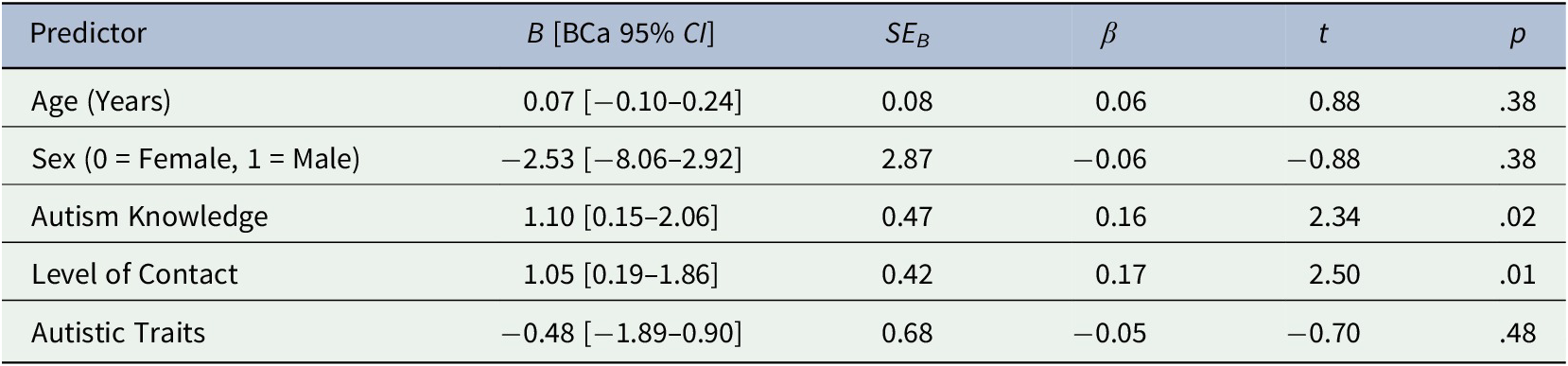

We had 80% power to detect small-to-medium unique associations in our regression (f 2 = .06, α = .05), that is, the primary analysis. Neither multicollinearity nor heteroscedasticity was a concern. The standardised residuals broadly followed a normal distribution and were not autocorrelated (Durbin-Watson statistic = 1.97, p = .81). Overall, data were suitable for and submitted to multiple linear regression analysis, F(5, 220) = 3.01, R 2 = .06, p = .01, revealing that greater autism knowledge and higher levels of contact, but no other variables, were significant predictors of favourable attitudes towards autistic people (Table 2).

Table 2. Multiple Regression Predicting Attitudes Towards Autistic People

Discussions

Neither age nor sex was uniquely associated with attitudes towards autistic people. The high percentage of young female participants reduces the generalisability of this finding, but equally, it is generally consistent with recent research in larger samples (e.g., Kuzminski et al., Reference Kuzminski, Netto, Wilson, Falkmer, Chamberlain and Falkmer2019). Therefore, it is unlikely that such socio-demographic factors are particularly important predictors of attitudes to autism but could practicably be accounted for in future research. Similarly, autistic traits were not significantly associated with attitudes to autism (see also, Gardiner & Iarocci, Reference Gardiner and Iarocci2014). There are ongoing concerns with measuring autistic traits in the general population (e.g., Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Livingston, Clutterbuck and Shah2020), which is a potential limitation of the study and many others in our field. Nonetheless, our finding is of interest as it is often assumed that people with many autistic traits have favourable attitudes towards autistic people and would therefore be good advocates for them (e.g., Komeda, Reference Komeda2015). This may not be the case and warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

The main conclusion from our study is that greater autism knowledge and higher levels of contact with autistic people are independently associated with favourable attitudes towards autistic people. It is notable that effect sizes were small and the study requires replication. Nevertheless, we tentatively suggest that increasing public knowledge of autism has the potential to improve attitudes towards autistic people. Equally, we suggest that increasing contact between autistic and non-autistic people may have an independent influence on attitudes towards autistic people, potentially via a different mechanism. Better understanding of their (separable) contributions to attitudes towards autistic people will be an interesting avenue in future research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Celyn Gabe-Jones and Katarzyna Konczewska for assistance with data collection, and Lucy A. Livingston for comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

PS, AS, and SC conceived the study. AS and SC collected the data. PS, AS, and SC analysed the data and wrote the article. AS and SC contributed equally to this work.

Funding Information

PS is supported by the GW4 Generator Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available as Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/exp.2020.46.

Comments

Comments to the Author: Congratulations on a good and important study. Minor edits to improve:

Introduction: I realise you are limited by word count, but if you can, I recommend being more explicit about HOW variables like age and sex affect attitudes towards autistic people (i.e. attitudes more positive if a person is older or younger, male or female?); and why this is important (e.g. negative impact of stigma).

Methods: Are participants university students? Was the study completed online?

Results: Table 1 hard to see where means and SD end and correlations begin. Even a dotted line or something to separate out these two parts of the table would help.

-Please specify the type of MLR - enter method, presumably?

- Not clear why you use both Spearman’s Rho and Pearson’s r - can you explain this?

Discussion: small thing, but the last sentence does not sit quite right with me I recommend “…assumed that people with many autistic traits have putatively favourable attitudes towards autism and would thus be good advocates for autistic people”.

Conclusion: I would remove “and additive” as to me it implies a statistical change that you don’t report (e.g. a change in R squared).