1. Introduction

False beliefs affect us in many ways. Fricker’s work on epistemic injustice directs our attention to the effects of a specific case of falsehood (Fricker, Reference Fricker2007).Footnote 1 She examines false beliefs about other people’s credibility arising from negative prejudices concerning a social group to which they belong and which is part of their identity. She argues that such false beliefs give rise to “testimonial injustice.” Such false beliefs lead us to assign a lower degree of credibility to what these people say than what is objectively warranted or justified, and by so mistrusting them, we wrong them in their capacity as knowers. People suffering such wrongs, Fricker maintains, are dishonored.

But what if the beliefs concerning their lowered credibility are true?Footnote 2

To ask this may seem odd – or worse; for apart from the question of whether we should call a belief about a person’s credibility a “prejudice” if it is true, what wrong could be done by mistrusting or disbelieving people on the basis of accurate assessments of their credibility? Or also, might asking this question not reveal some skepticism concerning the reality and seriousness of testimonial injustice?

So, let me clarify. My aim in this paper is to show that if we restrict our attention to false beliefs, a significant type of injustice is all too likely to escape our attention, namely, testimonial injustice that arises “self-fulfillingly.” Fricker (Reference Fricker2007) gestures towards something like self-fulfilling testimonial injustice herself in her discussion of Marge Sherwood’s predicament in Minghella’s screenplay for The Talented Mr Ripley. Marge’s fiancé, Dickie Greenleaf, has vanished after spending considerable time traveling with Tom Ripley. Tom puts forth the idea that Dickie took his own life – a theory that gains traction with both the police and Dickie’s father. Marge, however, is unconvinced. She suspects Tom of murder. And, crucially, she is right. Fricker’s sharp analysis of this case shows how Marge’s account of Dickie’s disappearance is steadily dismissed – both by Dickie’s father and the police – on the assumption that, as a woman, she cannot be trusted to give a clear or reliable report. Over time, and quite possibly as a result of this steady mistrust, Marge begins to take on the very traits they expect of her, becoming what Fricker calls a “hysterical female,” a shift that lays bare the distorting power of being persistently disbelieved:

Here we see poor Marge in some measure actually becoming what she has been constructed as: a hysterical female, apparently expressing herself in semi-contradictions, sticking to intuitions in the face of others’ reasons, unable to keep a grip on her emotions. Thus the sinister mechanism of causal construction. Perversely, we catch a whiff here of how such causal construction might seem to supply an eleventh-hour justification for the original prejudiced credibility judgement – such is the power that some prejudices have for self-fulfilment. [Herbert] Greenleaf’s wrongful credibility judgement of Marge cannot itself be retrospectively justified, however, for when the judgement was made, the evidence did not support it; still, it must be acknowledged that the frustrated and semi-articulate expressive form that Marge’s suspicions come to take, creates a terrible justificatory loop so that, given Greenleaf’s point of view, there is no irrationality on his part if he views her behaviour as confirming his perception of her as non-trustworthy. (Fricker Reference Fricker2007, pp. 88–89)

My aim in this paper is to deepen our understanding of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. The idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy has been a focus of social science research since the late nineteenth century, often shaped by a concern with racial discrimination. This paper seeks to draw on that body of work to shed new light on the workings of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

The structure of the paper is as follows. I begin by examining the mechanisms that might explain why an epistemic subject (“hearer”) assigns less credibility than is warranted to the words of a given “speaker.” This inquiry is necessary because, at first glance, it may seem puzzling to suggest that prejudice might lead individuals to dismiss information that is plainly useful to them. Drawing on recent work in economics, I outline, in Section 2, a model of testimonial injustice informed by research on “motivated cognition” and “cognitive bias.” This work is not only of independent interest but also serves as a background for the next stage of the argument: developing the notion of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice through the lens of game theory and empirical research, a task undertaken in Section 3. Section 4 turns to the harms of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice, particularly its corrosive effects on epistemic self-confidence and epistemic self-esteem, the latter being a concept introduced in this paper. Section 5 concludes.

2. Testimonial injustice

2.1 Background

Testimonial injustice on Fricker’s (Reference Fricker2007) count arises out of false beliefs about the credibility of particular people, which stem from negative prejudices concerning their social identity. One of Fricker’s examples is from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, a novel set in the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930s. The novel tells the tale of a black man, Tom Robinson, who stands trial on charges of raping a white girl. Despite overwhelming evidence in his favor, his testimony is set aside by the all-white jury on the basis of a widespread prejudice against the general trustworthiness of black men. Consequently, he is found guilty.

In a detailed and illuminating analysis of this episode from the novel, Fricker shows that all defining elements of testimonial injustice are present: negative prejudices about the lack of credibility of members of a disadvantaged class, which are pervasive and structural, epistemically unwarranted and unjustified, and caused by and/or constitutive of widespread relations of social domination. Fricker also argues that these conditions are essential for testimonial injustice in the sense that where they do not hold no such injustice takes place. The jury’s judgment about Robinson’s trustworthiness is wrong, and it is wrong because of pervasive prejudices against members of a dominated group, and not, say, because they mistake Robinson for someone else. For Fricker, this case also shows that the prejudice has to be sufficiently widespread and systematic, by which she means that it has to be caused or accompanied by other, non-epistemic injustices that affect the victim’s life more generally. In other words, the effects of the injustice have to be more than only local in time and place, and the prejudices have to be sufficiently widely shared among members of a dominating social group.

One might, however, find it mildly surprising that people should engage in testimonial injustice, particularly if one is influenced by the idea – still prominent in economics and other fields – that people largely attempt to maximize their desire satisfaction (expected utility maximization). Confronted with utterances carrying potentially relevant information, of a given level of credibility, what could make a person downgrade their ascription of credibility in a way that is not supported by the available evidence? They would be throwing away what may be useful to them now or later and what can be retained without any costs. Or so it would seem.

Fricker’s (Reference Fricker2007) take here is that she is particularly interested in cases in which credibility is downgraded because of “negative identity-prejudicial stereotype,” a concept she defines as a “widely held disparaging association between a social group and one or more attributes, where this association embodies a generalization that displays some (typically, epistemically culpable) resistance to counter-evidence owing to an ethically bad affective investment” (Fricker Reference Fricker2007, p. 35). So, one might think that it is the ethically bad affective investment that drives people to discard valuable information. But then again: why would someone form a stereotypical and disparaging association between certain traits and a particular social group if doing so undermines their own ability to judge accurately, especially when there are many other ways to indulge an ethically objectionable affective investment that do not demand the same sacrifice of rationality, and may, in fact, better serve their interests?

It is instructive to consider Robinson’s predicament again. In his case, the recipients of the testimony (the all-white jury) can hardly be seen as having a genuine interest in finding out the truth: they may not consider what Robinson says to be potentially relevant to their purposes as their actions may rather be driven by the mere desire to maximize the chances of Robinson’s incarceration. It is not unreasonable to read the novel as suggesting that they knew full well that Robinson was not involved in the rape and that they accepted – or perhaps even encouraged – his conviction, as they wanted to protect the real perpetrator. And, if we adopt this reading, it may not be necessary to assume the jury members genuinely believed the negative identity-prejudicial stereotype and compromised their epistemic rationality. Rather, they may not have believed the stereotype; but appealing to the stereotype helped them and others to advance their ethically bad affective investments, that is, their racism. Robinson’s case may, then, not be a typical case of testimonial injustice after all.

The Robinson case is the one in which (purported) testimonial injustice harms the person who is wronged by the injustice. Most of the cases figuring in the literature are of this kind, and understandably so. But that focus obscures the fact that discarding valuable information on epistemically irrational grounds may come at great personal risks. There are also cases in which testimonial injustice wrongs the victim, but where most of the harm accrues to the perpetrator. Here is an early example, due to Wanderer (Reference Wanderer2012). This is a scenario in which a (white) swimmer disregards a (black) lifeguard’s warning about the presence of dangerous sharks in the waters and dies in a subsequent shark attack. Here is what might have gone on, in Wanderer’s (Reference Wanderer2012, p. 150) words:

The lifeguard believed, truly as it turned out, that there was a shark in the water which posed a mortal danger to swimmers, and verbally conveyed this belief to the swimmer. In deciding whether to believe him, the swimmer ascribed some degree of credibility to his claim. This degree of credibility was a function of the plausibility of what he said in the light of what else she believed, and of the perceived trustworthiness of the lifeguard on this occasion. (Trustworthiness here included both an assessment of whether he was competent in making such judgements, and whether he was being sincere in his utterance.) The swimmer did not treat the claim as credible, and thus did not come to share the lifeguard’s belief.

Here the question of why a person would allow an ethically flawed affective investment to interfere with their epistemic rationality becomes all the more pressing. Why would the swimmer do exactly that? For this case to count as testimonial injustice, we must assume that the swimmer harbored a negative identity-prejudicial stereotype – that is, she maintained a stereotypical belief about a group to which the lifeguard belongs, resisted counterevidence that challenged it, and did so out of a morally objectionable affective commitment. So we have to assume that the swimmer had some evidence about the credibility of the guard’s warning, but instead of doing the epistemically rational thing, she assigned lower credibility to his warning, and because of that false credibility judgment she adopted her suboptimal belief about the risks of swimming. Rejecting the warning, then, led her to forgo to adopt a belief that would significantly increase her life expectancy.

What could explain such behavior?

Before proceeding, let me clarify why I am raising these questions here. For my argument about self-fulfilling testimonial injustice to succeed, it will turn out to be important to distinguish between the various factors at play when self-fulfilling testimonial injustice manifests itself.Footnote 3 My hope is that shedding new light here on cases familiar from the literature on testimonial injustice helps prepare the ground for introducing the concept of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice later, and in particular the use of research from economics. The point is essentially this. Assuming that people maximize expected utility, it is odd to explain certain types of behavior (the jury members, the swimmer) as resulting out of false beliefs that they could have corrected because the evidence was available. Persistently disregarding counterevidence diminishes expected utility by increasing the likelihood of acting on inaccurate beliefs, as the swimmer’s case exemplifies. This is not to deny the occurrence of epistemic irrationality but to underscore the need for inquiry beyond philosophy to assess its prevalence, intensity, and consequences. Testimonial injustice may, in fact, be less frequent than commonly assumed. Robinson may not have been a victim of testimonial injustice, and black lifeguards may rarely be wronged by white swimmers willing to endanger themselves through epistemic bias. What may occur more often – though less conspicuously – are instances in which credibility judgments, while ultimately accurate, acquire their accuracy through self-fulfilling mechanisms.

Philosophical inquiry into testimonial injustice has increasingly drawn upon interdisciplinary insights, with scholars finding valuable contributions in fields as diverse as history, anthropology, psychology, and the social sciences. The present paper engages primarily with economics, drawing in part on psychological research as well, and it is in this interdisciplinary engagement, I hope, that a key aspect of its novelty resides. A more detailed exposition of the specific strands of research informing my account will be provided when I introduce the concept of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. For now, my primary concern is with a body of recent empirical findings that demonstrate how individuals systematically ascribe less credibility than is warranted to others through two distinct cognitive mechanisms. The first, “cognitive bias,” arises from reliance on heuristics-driven belief formation, wherein simplifying assumptions are adopted to economize cognitive effort. The second, “motivated cognition” (also referred to as “motivated belief”) involves the strategic adoption of false beliefs in ways that yield non-epistemic utility to the agent. In what follows, I aim to examine how these mechanisms contribute to testimonial injustice, with particular attention to the structural and economic dimensions of their operation.Footnote 4

Motivated cognition occurs when people believe something because it fits or supports their (moral, political, religious, etc.) worldview. Influential work on fake news in the 2016 US presidential elections, for instance, showed that voters were much more likely to believe stories favoring their preferred candidate: people tend to believe things that they want to be true, or that support things they want to be true (Allcott and Gentzkow, Reference Allcott and Gentzkow2017). Motivated cognition affects beliefs about a large array of topics, and affects all worldviews, as is illustrated by the fact that even though Republicans/conservatives more frequently reject climate science research if it is at odds with certain values they hold dear, Democrats/liberals more frequently reject findings on gun control going against their respective fundamental ideals (Lewandowsky and Oberauer, Reference Lewandowsky and Oberauer2016; Washburn and Skitka, Reference Washburn and Skitka2017).Footnote 5

The second mode of non-evidential belief formation, cognitive bias, arises when individuals rely on heuristics-driven belief formation, that is, cognitive shortcuts that reduce cognitive effort while enhancing processing speed (Bénabou and Tirole, Reference Bénabou and Tirole2016). Unlike cases of motivated cognition, where the adoption of a false belief yields direct non-epistemic utility, cognitive bias does not confer benefits through the content of the belief itself. Rather, its utility derives from the economization of cognitive resources: heuristics-based reasoning facilitates rapid belief acquisition by bypassing the demands of more effortful, reflective cognition. While heuristics may often lead to epistemically reliable outcomes, they are also susceptible to systematic distortions, particularly in testimonial contexts where credibility judgments are at stake.Footnote 6

Motivated cognition and cognitive bias will generally operate simultaneously (Wyer and Albarracín, Reference Wyer, Albarracín, Albarracín, Johnson and Zanna2005), and hence it is a considerable challenge to tell apart their respective contributions to false beliefs empirically. An example of a study that takes up this challenge is Kahan (Reference Kahan2013).Footnote 7 Kahan found evidence that individuals with advanced cognitive skills display cognitive bias less because their advanced skills help them avoid (to some extent) the use of unjustifiably simplistic heuristics. Yet individuals with advanced cognitive skills are found to display motivated cognition more frequently (i.e., to believe things because of their worldview) since, the study suggests, their more advanced cognitive skills somehow facilitate “tweaking” the interpretation of purported evidence in ways that match their worldview.

Motivated cognition and cognitive bias not only affect individual but also collective belief formation, as it happens in work teams, business units, or Facebook groups (Derks et al., Reference Derks, van Laar and Ellemers2009). This includes phenomena such as the negative stereotyping of outsiders (“you are either with us, or against us”), self-censorship (group members keeping silent to avoid expressing disagreement) (Bénabou, Reference Bénabou2013), and self-stereotyping (individuals are less willing to contribute ideas to team discussions in areas that are stereotypically outside of their gender’s domain) (Bordalo et al., Reference Bordalo, Coffman, Gennaioli and Shleifer2016).

2.2 Motivated cognition

Motivated cognition and cognitive bias, I will now argue, provide critical insight into the mechanisms underlying testimonial injustice. While my project aligns in certain respects with those of Fricker (Reference Fricker2007) and Origgi (Reference Origgi2012), the body of research on motivated cognition has developed more recently, and my aim here is to contribute new input to this discussion (Munroe, Reference Munroe2016). Specifically, I propose that distinguishing between two “ideal types” of testimonial injustice – one rooted in motivated cognition and the other in cognitive bias – yields explanatory advantages.

Consider a case in which a hearer attributes less credibility to a speaker than is warranted by the available evidence. What advantage might this confer upon the hearer? Research on motivated cognition suggests an answer: beliefs possess not only epistemic but also non-epistemic value or utility. This means that, in some cases, it may be instrumentally rational for an individual to avoid adopting beliefs for which they possess evidence, or to embrace beliefs for which they do not. It is this mechanism that explains why Republicans systematically lower the credibility they assign to climate scientists (and Democrats to experts on gun control). Moreover, nothing precludes the possibility that members of a dominant social group might derive analogous non-epistemic utility from discrediting members of a subordinated group. In Fricker’s (Reference Fricker2007) terms, this non-epistemic utility would be proportional to the extent to which the deflation of credibility serves to reinforce the ethically bad investment at the core of a negative identity-prejudicial stereotype.

It is important to note that research on motivated cognition does not imply that individuals who engage in it are always fully aware of all the reasons underlying their beliefs. While in some cases, people may recognize that they are engaging in motivated cognition, they may also develop a tendency to disbelieve speakers from certain social groups in a way that operates outside their conscious awareness. The activation of such credibility judgments may bypass deliberate reflection, functioning instead as an ingrained cognitive response.Footnote 8 Indeed, it is plausible that these deflated credibility judgments develop gradually over time, alongside other behavioral and attitudinal manifestations of racism or other forms of prejudice in which the individual is already invested.

Motivated cognition, in my view, represents the most archetypical form of testimonial injustice, as the fact that a hearer derives non-epistemic utility from assigning less credibility to a speaker than is warranted may be taken to indicate a genuine injustice rather than a mere epistemic error. I take Wanderer’s (Reference Voigt2012) case of the swimmer to be best understood as an instance of motivated cognition. While it is unlikely that the swimmer was consciously aware of downgrading the lifeguard’s credibility in an epistemically irrational manner at the moment she dismissed the warning, she may well have developed a broader tendency to hold a false belief about the credibility of people of color, a belief that provides her with non-epistemic utility by aligning with her racism.

Motivated cognition-based testimonial injustice constitutes the central case of testimonial injustice and may indeed be the only genuine instance of it. It operates through a negative identity-prejudicial stereotype that the individual resists revising due to ethically bad investments. The persistence of these deflated credibility judgments, along with a broader set of incorrect generalizations about the social group in question, provides non-epistemic utility to the individual, reinforcing the underlying prejudice and sustaining a systematically distorted epistemic landscape.

Empirical research on non-evidential belief suggests that motivated cognition-based forms of testimonial injustice are likely to be relatively rare, though. Most incorrect credibility judgments contributing to testimonial injustice appear to be better explained by cognitive bias. The empirical literature strongly supports the view that the fact that certain beliefs misrepresent disadvantaged social groups does not necessarily imply that these beliefs are rooted in negative attitudes toward those groups. They need not be the result of ethically bad investments. Rather, these beliefs – false as they are – seem to stem from a fundamental aspect of human psychology: the tendency to prioritize speed and efficiency in reasoning, favoring cognitive shortcuts that reduce effort. Studies indicate that people frequently rely on evidence or information containing a “kernel of truth,” but fail to interrogate that kernel further (Bordalo et al., Reference Bordalo, Coffman, Gennaioli and Shleifer2016). The consequence is an insufficient appreciation of the fact that this limited evidence does not support fully reliable, epistemically sound beliefs. As a result, individuals may fail to recognize the extent to which their beliefs are significantly inaccurate. These beliefs distort perceptions of particular social groups, yet they do not stem from an ethically bad investment, and, consequently, would not qualify as testimonial injustice in the strict sense.

2.3 Cognitive bias

My aim so far has been to clarify the type and extent of testimonial injustice that one should expect to encounter in practice, and a central point has been that what may initially appear to involve incorrect deflated credibility judgments may require different explanatory frameworks. In this context, I have suggested that the Robinson case need not necessarily be construed as an instance of testimonial injustice. While the jury members undoubtedly exhibited an ethically bad affective investment, the advancement of this investment could have been achieved more efficiently through means and methods that do not entail epistemic irrationality. This raises the possibility that not all cases of prejudicial credibility deficits qualify as testimonial injustice in the strict sense, particularly when alternative, non-epistemic mechanisms account for the underlying injustice.

If the Robinson case does not constitute testimonial injustice – or at least need not be seen as such – then what exactly is the phenomenon at stake when we speak of testimonial injustice? This question is central to my argument, as I ultimately seek to show that the most pernicious credibility-related phenomenon affecting members of socially disadvantaged groups with a history of ethically bad affective investments does not necessarily involve false credibility judgments but rather true ones. While I do not deny the reality of testimonial injustice in the strict sense, my project calls for an expansion of the conceptual framework, which may lead to the conclusion that the actual incidence of testimonial injustice in its strictest form is smaller than commonly assumed. In particular, self-fulfilling testimonial injustice may come out as a more prevalent form after all. However, due to the methodological constraints of empirical research in this area – particularly its reliance on samples that are not nationally representative – precise estimates of its prevalence remain, to my knowledge, unavailable. This suggests that the focus should not merely be on identifying testimonial injustice as traditionally conceived but also on recognizing and addressing broader credibility-related injustices that may be equally, if not more, damaging.

Before turning to self-fulfilling testimonial injustice, in which, as noted, the hearer forms true beliefs about the speaker, I want to consider a different type of case – one in which the hearer holds false beliefs about the speaker, yet where these beliefs need not be characterized as testimonial injustice, as they do not necessarily stem from an ethically bad affective investment. This type of false judgment arises due to cognitive bias. To illustrate this, I draw on an approach that has been particularly influential in economics, developed by Bordalo et al. (Reference Bordalo, Coffman, Gennaioli and Shleifer2016). The authors present a model of what they term “stereotypical” beliefs, which sheds light on how cognitive simplifications give rise to distorted credibility judgments.Footnote 9 Their starting point is a toy example involving the stereotype that “Florida residents are elderly.” While this example is relatively neutral compared to the types of false beliefs that characterize standard cases of testimonial injustice, it provides a useful illustration of how simplified reasoning can lead to cognitive bias, and, consequently, to systematically false beliefs.

So why would one believe that Florida residents are elderly?

If we consider the percentage of elderly people in Florida, it is hard to see how anyone could hold this belief: only 17% are 65+. The biggest age bracket is 20–44 years, which represents about 32% of Floridians. However, the authors of the study provide evidence that when we form this type of belief, we do not select the most likely age bracket (which would result in our believing that “Florida residents are between 20 and 44 years of age”), as this would require more detailed categorizations than what people normally engage in. So, rather, the cognitive bias we are prone to is that we select the age bracket that happens to have the highest relative frequency across a set of salient “comparables.” We should focus here on the percentage of 65+, which is indeed much higher than the nationwide average. Floridians are considered elderly in the sense that Florida has the highest proportion of elderly residents among the states included in the comparison. As Bordalo and colleagues describe it, elderly individuals are “representative” of Florida. They formalize this “logic of representativeness” by way of a variant of a “likelihood ratio.”Footnote 10 The idea is that one computes the probability of a random Florida resident being 65+ and compares it with the probability that a random US resident is 65+ and divides the former by the latter, which in the present example would be 17 divided by 13. Continuing this for other states (so comparing Florida with other states), one would then observe that Florida comes out highest. And it is that fact that according to Bordalo et al. (Reference Bordalo, Coffman, Gennaioli and Shleifer2016) explains the stereotype.

Using this logic of representativeness, let us turn our attention to a set of false beliefs that underlie one of the most paradigmatic cases of stereotype and prejudice: racist credibility judgments. To carry out this exercise, we need actual statistical data, just as in the case of the Florida example, to compute likelihood ratios. Ideally, of course, we would have precise data about the actual credibility of white people and people of color with respect to a certain domain of knowledge, but such data are not generally available. So we need to take a proxy for what counts as a person’s “general” knowledge, and the most widely used and available such proxy is educational achievement, as captured by the US census. Taking education as a proxy for a person’s general knowledge or credibility is surely not perfect, but where statistics are course-grained, we have to use approximations.

The 2020 US census gives the following figures: 21% of Hispanics have a bachelor’s degree (or higher), 28% of Blacks, 42% of non-hispanic Whites, and 61% of Asians, with a national average of 38%. Applying these figures, the logic of representativeness suggests that, if there are any stereotypes concerning educational achievement, then it is likely that Hispanics and Blacks will be stereotyped as having low education, and Asians as having high education.

The logic of representativeness is a model developed by economists to explain stereotypes. The suggestion is not that people explicitly engage in this type of calculation before forming a judgment. Nor is the idea that individuals consciously go through this type of reasoning process. In line with the tradition of economics from which this body of research is drawn, the claim is rather that the logic of representativeness explains the rationale behind this particular cognitive bias, while the bias itself operates more automatically in the background. As with other false beliefs, judgments of this kind may be adopted and transmitted through various mechanisms, to be identified and analyzed through empirical research. For my purposes here, what is important is that this research suggests that such false beliefs need not be grounded in ethically bad affective investments. There is no need to postulate negative attitudes toward Florida or the elderly to explain why people may come to believe that Florida residents are elderly. Likewise, racism does not need to be invoked to account for the belief that people of color are uneducated. The belief is false. It is potentially harmful. But while it will undoubtedly be held by most racists, racism itself need not be what explains why people come to hold it.

If what I have said so far is plausible, then it may seem that false deflated credibility judgments about people of color no longer necessarily count as testimonial injustice. That is indeed the position defended here. One may want to allow this type of deflated credibility judgment to be covered by a loosened notion of testimonial injustice, contrasting with testimonial injustice sensu stricto. But the upshot remains the same: not all deflated credibility judgments constitute testimonial injustice. This is not a new insight per se. It is, in fact, something that Fricker (Reference Fricker2007) already acknowledges. What I aim to do here, however, is to provide an empirically informed account that, I hope, will contribute to answering questions about the prevalence of testimonial injustice. My view is that there exists a broad spectrum of phenomena involving credibility judgments that negatively impact members of disadvantaged social groups. Some of these credibility judgments are false and rooted in ethically bad attitudes toward these groups. Others are false but not grounded in such attitudes. And some, indeed, are true, but self-fulfillingly so. One might choose to reserve the term testimonial injustice for the first category. However, the argument put forward in this paper is that doing so risks overlooking the fact that other forms may be more prevalent, more harmful, less easily detected – and in many cases ultimately caused by injustices nonetheless.

To support this last claim, consider the case of mistaken beliefs about the lower credibility of people of color. While it may be understandable that such beliefs arise, the logic of representativeness makes it painfully clear that the key causal factor generating them is the underrepresentation of people of color in higher education. It goes without saying that access to higher education has historically been, and continues to be, severely limited for people of color, and to the extent that these limitations are unjust or result from injustice, the mistaken credibility judgment has its causal origin in historical injustices. This should not be a contentious claim. My point here is that an empirical study of mistaken credibility judgments may reveal the ways in which they are linked to broader patterns of injustice, ideally providing input for social reform. This is also the motivation behind introducing the concept of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. Let me now turn to that topic.

3. Self-fulfilling testimonial injustice

Motivated cognition-based and cognitive bias-based testimonial injustice both involve false credibility judgments. As my exposition of the logic of representativeness demonstrates, cognitive bias-based testimonial injustice is not rooted in ethically bad affective investments on the part of the hearer. Moreover, while cognitive-biased based judgments are false, they contain a kernel of truth. They are, if one wishes, less false than the credibility judgments produced by motivated cognition. Self-fulfilling testimonial injustice extends this pattern further. Like cognitive bias-based testimonial injustice, it is not grounded in ethically bad affective investments on the part of the hearer. However, in this case, the credibility judgments are no longer false. Self-fulfilling testimonial injustice consists of credibility judgments that do not merely contain a kernel of truth but are, in fact, fully accurate: the hearer’s belief concerning the lowered credibility of the speaker is, as a matter of fact, true.

As there will be statistical differences between such things as educational achievement in any given population, it is quite likely that in given circumstances there will be a social group that has, on average, lower educational qualifications than the national average. As we saw, the logic of representativeness will then explain why people would adopt the belief that members of this group are lowly educated. Adopting this belief is epistemically irrational, but it happens owing to the general efficiency factors that explain cognitive bias. Now suppose, for the sake of argument, that someone is among the first individuals to adopt this belief. How does such an early adopter contribute to the spread of the belief? There are two possible scenarios, the second of which leads directly to the topic of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

In the first scenario, early adopters speak about members of the respective social group in disparaging ways, thereby propagating the belief, at least insofar as they are believed by those they communicate with. Here, the false credibility judgment spreads through communication. If this is the only mechanism at play, and the communication is sufficiently intense to ensure broad dissemination, then we arrive at a situation in which a significant portion of the population comes to hold the false credibility judgment. The second scenario arises when early adopters of the epistemically irrational false credibility judgment adjust their behavior toward members of the respective social group. As a consequence of this altered behavior – and through a further concatenation of events – the belief ultimately becomes true in a self-fulfilling manner. The aim of the remainder of this section is to explain how all this unfolds.

3.1 The Thomas theorem

That certain beliefs can become true by believing them is not a new insight. It is the content of the Thomas theorem, due to the American sociologists William and Dorothy Thomas (Reference Thomas and Thomas1928). It is to the effect that if people “define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (p. 572). This theorem was popularized by Merton (Reference Merton1948), a sociologist whose article on the self-fulfilling prophecy is a locus classicus in the literature. He described a self-fulfilling prophecy as “in the beginning, a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false conception come true” (Merton Reference Merton1948, p. 175).

To explain the phenomenon, Merton considers the example of a rumor about a particular bank being insolvent. Rumor has it that the bank will not be able to repay all of the savers’ deposits. This rumor, Merton shows, soon gives rise to a particular form of behavior that makes the rumor self-fulfillingly true. The wider the rumor spreads – leading more people to believe the bank is insolvent – the greater the number of withdrawals, until eventually, the bank can no longer meet its obligations to the next client in line. With no remaining funds, the bank collapses, and the initially false rumor becomes true.

If the influence of self-fulfilling beliefs were restricted to bank runs, there would perhaps not be much reason to study the concept in much detail. A large body of research in the social sciences shows, however, that self-fulfilling beliefs are implicated in a wide variety of contexts. To understand the mechanism underlying self-fulfilling beliefs, let us look at the rumor again. When depositors hear the rumor that their bank lacks cash, this gives them a reason to attempt to rescue their deposits by withdrawing them. Their belief in the bank’s insolvency, coupled with their desire to protect their savings, motivates them to withdraw their deposits. As more depositors do so, the cumulative effect leads to the bank’s eventual collapse.

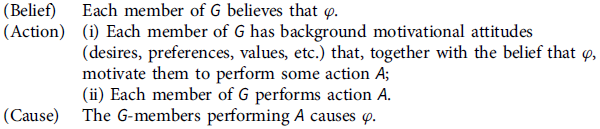

Three conditions have to be satisfied for the rumor to become self-fulfillingly true, involving belief (to the effect that the rumor is true), action (withdrawing money), and causation (withdrawals cause the bank’s collapse). More generally, for a group of people G to believe a proposition φ self-fulfillingly, the following three conditions have to hold (Biggs, Reference Biggs, Bearman and Hedström2011):

While these conditions capture the core of self-fulfilling beliefs, adjustments will have to be made to accommodate temporal and interpersonal variations. For instance, a more precise analysis of a bank run would start with only one person believing that the bank is in trouble, and therefore withdrawing money. A second person might obtain information about this, and therefore adopt the same belief and carry out the same action, and so forth. The necessary adjustments to incorporate this are straightforward.

It is important to emphasize that the bank run example should not obscure the core motivation behind Merton’s work – achieving a more precise understanding of the causes of racial discrimination. Merton examines in detail how self-fulfilling prophecies operate within prejudices held by unionists in the 1930s, specifically the belief that people of color were strikebreakers. This belief led unions to exclude them, which in turn pushed them into strikebreaking roles, thereby reinforcing the original prejudice. Similarly, he discusses the assumption that people of color lacked marketable skills, which resulted in limited investment in their education – an underinvestment that ultimately contributed to the very skills gap the prejudice presumed to exist.

Merton’s claims have been challenged on the grounds that, for racial discrimination to be genuinely self-fulfilling, a specific counterfactual must hold – namely, that in the absence of prejudice, discriminators would behave differently, that is, in a non-racist manner. Authors such as Biggs (Reference Biggs, Bearman and Hedström2011) question whether, in the 1930s, unions would have admitted people of color, and whether governments would have invested more in their education had such prejudices not been present. In my analysis of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice, I will provide evidence supporting the relevant counterfactuals while acknowledging that modifications may be required to the general framework of self-fulfilling prophecies. My argument draws on two strands of economic research on self-fulfilling beliefs. The first employs a game-theoretical model, which I will present in a largely non-formalized manner. The second is a field experiment that offers empirical validation of the mechanisms underlying self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

Before proceeding, it is important to consider the differences between these economic methods (Neumark Reference Neumark2018). Game theory is a branch of economics that develops mathematical models of strategic interactions between economic agents (de Bruin, Reference de Bruin2005). Field experiments, by contrast, involve gathering empirical data on real economic behavior – that is, behavior observed outside of controlled laboratory settings – and analyzing these data using econometric statistical tools. The role of models is to lay bare the precise assumptions under which particular economic outcomes should be expected, as well as the factors that contribute to such outcomes. Field experiments, in turn, provide insight into these phenomena as they unfold in concrete circumstances. Economists and policymakers value both methods, along with a range of other experimental, empirical, simulation, and theoretical approaches that I set aside for the purposes of this paper, as they serve complementary roles. It is standard practice to base policy recommendations on research that employs a variety of methodological approaches, and I will follow the same principle here. The value of using game theory in this context lies in its capacity to make explicit the structure of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice within a rigorously specified model. The value of using a field experiment is that it provides empirical evidence of how self-fulfilling testimonial injustice manifests in practice. The two approaches discussed below pertain to labor market discrimination. This focus is partly due to the extensive body of economic research on this particular form of discrimination and partly because labor market discrimination is arguably among the contexts where its effects are most pernicious (Darity, Mullen, and Slaughter, Reference Darity, Mullen and Slaughter2022).

3.2 Theoretical model

To position the model introduced here, it is useful to briefly summarize the main insights from economic approaches to discrimination. The standard view distinguishes between two forms of discrimination: “taste-based” discrimination and “statistical” discrimination. Taste-based discrimination in the labor market arises from the negative attitudes of employers, employees, or customers toward members of particular social groups. In the terminology of the testimonial injustice literature, these “tastes” reflect negative identity-prejudicial stereotypes that reveal ethically bad affective investments. The negative attitudes in question concern a range of social categories, including race, ethnicity, physical appearance, obesity, gender, sexual orientation, age, and disabilities, among others (Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2018; Klumpp and Su, Reference Klumpp and Su2013; Neumark, Reference Neumark2018).

The idea is best introduced through a standard example from the literature: taste-based discrimination by a racist employer. Consider first an employer without negative attitudes. The utility the employer derives from running their business is simply equal to the profits π they generate, such that U(π) = π. In this case, the employer’s utility is unaffected by whether these profits are generated through the employment of members of particular social groups. For a racist employer, however, utility depends not only on the profits π realized but also on a disutility term associated with hiring employees of color. This can be expressed as U(π, C) = π – d · C, where d > 0 is a constant, and C is the number of workers of color employed in the business.

One might expect this to result in a labor market where no people of color are hired, but this is not necessarily the case. Standard economic reasoning shows that an equilibrium may arise in which the wage paid to white workers, wW, equals the wage paid to workers of color, wC, plus the discrimination cost, such that wW = wC + d. This occurs because if workers of color accept a wage differential of d, the employer’s disutility from hiring them is offset by the reduced wage costs.Footnote 11 If d varies across employers – which is a plausible assumption – then some employers may exhibit stronger preferences for hiring only white workers, while others may be willing to hire workers of color at a wage discount. The degree to which this discrimination manifests in actual hiring decisions thus depends on the distribution of d across firms in the labor market.

The model assumes that white workers and workers of color are perfect substitutes, meaning that they are equally productive. This assumption is crucial because, if productivity differences existed, what appears to be discriminatory hiring decisions could instead be interpreted as rational business behavior: workers with lower productivity generally earn lower wages or are less likely to be hired. By assuming perfect substitutability, the model isolates discrimination as the explanatory factor for wage disparities and hiring preferences, preventing productivity-based justifications from obscuring the role of bias. This assumption also leads to the conclusion that, in a competitive labor market, employers with racist attitudes would eventually be driven out. Non-racist employers would hire workers of color at wages lower than wW, allowing these employers to secure a cost advantage and earn higher profits than their racist competitors. Over time, the economic pressure to maximize profits would incentivize firms to hire workers based on productivity rather than prejudice, leading to the gradual displacement of discriminatory employers by those prioritizing economic efficiency. Yet, while competition does reduce discrimination in some markets, markets are often not fully competitive. Moreover, other mechanisms contribute to persistent disparities, particularly because workers generally differ in productivity. This brings us to the second economic approach to discrimination, known as statistical discrimination.

Statistical discrimination in the labor market arises when employers lack complete information about the variation in productivity, skills, or other relevant characteristics within social groups and instead rely on the information they do have. One of the earliest models illustrating this phenomenon was developed by Phelps (Reference Phelps1972). His model examined a situation in which, due to historical disadvantages, people of color were on average slightly less productive than white workers. While there are certain individual workers of color who are more productive than some white workers, employers – lacking precise information about individual productivity – make hiring and wage decisions based on group averages. As a result, they systematically offer higher wages to white employees, reinforcing disparities even when explicit bias is not at play.

Building on the foundational contributions of Phelps and others, Coate and Loury (Reference Coate and Loury1993) developed a formal model illustrating how negative stereotypes about productivity can become self-fulfilling within labor markets.Footnote 12 Their framework demonstrates how an equilibrium can emerge in which employers’ initial beliefs about productivity disparities between racial groups, though not necessarily grounded in objective differences, become reinforced through the very mechanisms those beliefs set in motion.

The structure of such models follows a systematic sequence.Footnote 13 The first element is that employers, lacking precise individual-level information, face comparable uncertainty when evaluating the productivity of both white workers and workers of color. Yet second, rather than withholding judgment, they assume – without sufficient warrant – that workers of color are less likely to invest in skill acquisition and professional development. Acting upon this belief, they, third, impose stricter evidentiary demands, requiring more extensive proof of qualifications and training from workers of color than from their white counterparts. Finally, confronted with these heightened barriers and anticipating lower returns on investment, workers of color rationally invest less in education and training, thereby reinforcing the very stereotype that constrained their opportunities in the first place.

Thus, the employer’s initial belief – that workers of color invest less in their human capital – comes to appear validated, not because it was accurate from the outset, but because it has shaped the very conditions under which it is confirmed. The model illustrates how labor market inequalities can persist even in the absence of explicit racial animus. A mistaken presumption, once acted upon, ultimately manifests as self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

3.3 Field experiment

This dynamic is not merely theoretical but has been observed in empirical studies examining the ways in which biased expectations shape real-world economic and workplace outcomes. One such study, conducted by Glover et al. (Reference Glover, Pallais and Pariente2017), offers a detailed examination of how managerial bias influences employee performance. In a painstakingly detailed and pioneering study, these scholars investigated the impact of racist managers on the performance of cashiers in a French grocery chain. Initially motivated by the idea that they might demonstrate the effect of so-called “stereotype threat” outside the psychology laboratory, they hypothesized that minority cashiers (with a North African or Sub-Saharan origin) who have racially prejudiced supervisors/managers will show decreased performance as compared to minority cashiers who have non-prejudiced managers, on the grounds of the demonstratively salient stereotype that minority cashiers are “lazy.” Stereotype threat refers to the purported phenomenon that when a member of a particular group is confronted with a negative stereotype concerning their group (for instance, minority cashiers are lazy), they will perform less on tasks related to the stereotype as compared to a situation in which the stereotype is not salient. And indeed, minority cashiers who have a prejudiced supervisor (and as a result are more likely to be exposed to the stereotype that minority cashiers are lazy) are found to scan products more slowly and to take more time between customers, as compared to cashiers supervised by non-prejudiced managers.

This pattern closely resembles what might be expected under a stereotype threat effect: it is plausible to assume that minority cashiers recognize their manager’s racial prejudice and the perception that they are “lazy,” which could, in turn, trigger the disabling mechanism associated with stereotype threat. However, through careful empirical and statistical analysis, Glover and colleagues demonstrate that while stereotype threat cannot be entirely ruled out, a far more likely explanation for the underperformance of minority cashiers is the reduced interaction they receive from prejudiced managers. These managers tend to supervise minority cashiers less, either due to discomfort in engaging with them or out of a desire to avoid appearing overtly biased. This pattern aligns with what the authors describe as “aversive racism.” Since reduced interaction results in less oversight from supervisors, and since monitoring is positively correlated with job performance, it follows that the relative lack of engagement leads to lower productivity among minority cashiers.Footnote 14

This study reveals a self-fulfilling mechanism at work. Three key observations illustrate this process. First, and unsurprisingly, prejudiced managers hold negative views about the competence and work ethic of minority cashiers. Second, as a manifestation of aversive racism, these managers avoid interacting with minority cashiers, supervising and monitoring them less frequently than their non-minority counterparts. Third, this reduced supervision leads to lower productivity among minority cashiers, reinforcing the initial bias of the managers.

While this aligns with the structure of self-fulfillingness outlined earlier, it does not capture the full extent of the phenomenon, though. The study also allows us to evaluate the counterfactual introduced before: what would happen if the prejudiced manager was absent? The findings reveal that, in the firm as a whole, the actual productivity of minority cashiers matches that of non-minority cashiers. How can this be the case when minority cashiers underperform under prejudiced supervisors? Glover and colleagues argue that the firm’s hiring standards for minority cashiers are systematically higher. Minority cashiers, when placed under the supervision of non-prejudiced managers, actually outperform majority cashiers hired by the firm; but in the presence of prejudiced managers, their performance is reduced to match that of their non-minority peers. From the perspective of hiring managers, however, this reinforces the belief that equal productivity between groups can only be achieved by imposing higher qualification thresholds on minority applicants. The consequence is clear: when a hiring manager is faced with two equally qualified candidates – one minority, one majority – they are more likely to select the majority candidate, assuming the minority candidate to be less competent.

This cycle exemplifies self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. Prejudiced managers systematically undervalue the expertise and productivity of minority cashiers, and through their behavior, they generate the very evidence that appears to confirm their biases. The underperformance of minority cashiers does not reflect an inherent lack of competence but rather the structural effects of prejudiced managerial behavior. Crucially, this is not a case of straightforward labor market discrimination alone; it is a case in which credibility judgments – about competence, work ethic, and productivity – play a central role in shaping professional outcomes.

One might object that this should not be considered a case of testimonial injustice on the grounds that a cashier’s work is not inherently epistemic. However, this line of reasoning risks adopting an unduly narrow and elitist conception of what counts as epistemic labor. There is no principled reason why the performance of manual or service-based tasks should not be affected by testimonial injustice in ways similar to those observed in more conventionally epistemic fields. While, to my knowledge, no empirical study to date has examined testimonial injustice in archetypically epistemic professions through a similar experimental framework, the mechanisms at play here could plausibly extend to such contexts. Moreover, there are strong grounds for including non-propositional knowledge – particularly skill-based know-how – within the broader category of testimonial injustice.Footnote 15 A woman dismissed as a plasterer because of the belief that only men can do such work suffers the same epistemic injustice as a woman whose mathematical ability is doubted for gendered reasons. The distinction between knowing how and knowing that should not obscure the broader mechanisms of exclusion and credibility misattribution that underpin self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

4. Harms and wrongs

Testimonial injustice occurs when a hearer unjustifiably downgrades a speaker’s credibility due to a negative prejudice about the speaker’s social group. I began this paper by asking how such a phenomenon can arise. If a hearer knows their credibility assessment is erroneous, correcting it is in their interest to avoid losing valuable information. If they do not know and could not have known they are in error, no injustice seems to occur. And if the credibility assessment is accurate, the hearer is epistemically justified. Testimonial injustice may, then, seem puzzling. This paper has sought to resolve the puzzle using insights from economics.

To conclude, I consider one final question: what is wrong about testimonial injustice (Congdon, Reference Congdon, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017)? Fricker (Reference Fricker2007) argues it wrongs people in their capacity as knowers, dishonoring them. She describes this as the “primary harm” of testimonial injustice or an “intrinsic” injustice (p. 44). Beyond this, testimonial injustice also produces “follow-on disadvantages” (p. 46), or secondary harms. A “practical” harm occurs in cases such as wrongful convictions in court. An “epistemic” harm arises when repeated instances of testimonial injustice erode confidence in one’s beliefs or knowledge-generating abilities. The remainder of this paper focuses on the epistemic secondary harm of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. This is not to downplay its practical harms, which earlier sections have shown to be significant. Rather, incorporating economic insights provides new ways to understand what is wrong with testimonial injustice. Given space constraints, this discussion will remain a “charcoal sketch.”Footnote 16

Before proceeding, it is necessary to consider whether self-fulfilling testimonial injustice constitutes a primary harm. Does it wrong subjects in their capacity as knowers? I argue it does not, though little hinges on this for my broader argument. The reason is that in cases of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice, credibility assessments are accurate. This does not lessen its damage – on the contrary, its subtlety makes it potentially more harmful. However, it is essential to distinguish these wrongful beliefs from the accurate credibility judgments made under conditions of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice.

I begin with epistemic self-confidence or epistemic self-trust.Footnote 17 Confidence or trust in a person depends, among other things, on perceptions of their capacity to perform certain tasks. I trust someone in a given domain when I have good reasons to believe they possess relevant expertise. Epistemic self-confidence, in this view, is a sense of possessing sufficient expertise in particular domains of knowledge – an awareness of oneself as a capable knower. It is crucial to functioning as an epistemic agent. If essential domains of one’s life become epistemically inaccessible due to a lack of self-confidence, one will hesitate to seek knowledge, maintain expertise, or share skills. This suggests that epistemic self-confidence is a precondition for trustworthiness. People lacking self-confidence will see no incentive to develop the knowledge necessary to extend their credibility. Just as mountaineers need self-trust to be trusted by their team, it would be unreasonable to trust someone’s testimony if they lacked trust in their own capacities. This suggests that self-fulfilling testimonial injustice systematically undermines epistemic self-confidence in affected social groups.

The harm is exacerbated by the difficulty individuals face in detecting its effects. Self-trust can be excessive or deficient, making it necessary to clarify that reducing an overblown sense of ability is not necessarily objectionable – it may even be required. However, when we speak of diminished self-confidence, we typically refer to cases where it falls below warranted levels. This is particularly relevant to self-fulfilling testimonial injustice, which lowers epistemic self-trust in ways that ensure its alignment with reduced credibility. One could say that it diminishes both a person’s self-confidence and their actual credibility without creating a mismatch between what they trust themselves to be capable of and what they are actually capable of. In the case of aversive racism, for instance, the manager’s beliefs reflect a lower level of performance and education. Because there is no apparent mismatch between belief and actual ability, self-fulfilling testimonial injustice is difficult to detect. Without careful scrutiny, as in the case of the French grocery chain, such injustice would likely go unnoticed. Moreover, its consequences are equally elusive, as perceived and actual credibility levels appear to align, reinforcing the illusion of an impartial assessment.

This does not bode well for those who want to rectify self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. It makes instances of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice hard to detect. It makes their negative consequences difficult to recognize, as there is no mismatch between the perceived credibility and actual credibility of the affected people.

Yet, self-fulfilling testimonial injustice does not only shape epistemic self-confidence; it also affects epistemic self-esteem. People derive esteem from their epistemic contributions within social contexts – whether through the knowledge they share, the skills they demonstrate, the insights they provide, or the wisdom they cultivate. Esteem, by its nature, is socially mediated, tied to the acknowledgment of one’s contributions to shared goals. Epistemic self-esteem, in turn, is the awareness of one’s capacity to make meaningful epistemic contributions within a given community.

Esteem and trust are closely intertwined; one cannot genuinely value another’s epistemic contributions without also placing trust in their capacities. A decline in epistemic self-confidence, then, necessarily undermines epistemic self-esteem. Aversive racism and similar forms of testimonial injustice may systematically erode epistemic self-confidence, yet not all cases lead to this outcome. Some individuals retain confidence in their epistemic abilities despite being subjected to systemic credibility deficits. Even so, epistemic self-esteem may still be affected.

Someone who recognizes that their own credibility remains intact may not lose trust in their abilities, yet they remain acutely aware of the persistent negative evaluation of the epistemic contributions associated with their social group. The awareness that one’s contributions are devalued or ignored by members of a dominant group can weaken epistemic self-esteem. It is difficult to maintain esteem for one’s epistemic contributions when they are systematically disregarded or dismissed. If those in positions of power fail to recognize or acknowledge one’s epistemic labor, then those contributions may seem to lack meaning or hold only marginal significance. Even where epistemic self-confidence remains intact, the broader epistemic environment shaped by testimonial injustice can still exert a corrosive effect on epistemic self-esteem.

5. Conclusion

Let me summarize the central claims of this paper. I have introduced a distinction between motivated cognition-based and cognitive bias-based testimonial injustice, drawing on recent research in economics and psychology, particularly work on the logic of representativeness. I then incorporated theoretical and field experimental work to develop the concept of self-fulfilling testimonial injustice. I examined the harms and wrongs associated with testimonial injustice, arguing that it erodes epistemic self-confidence, and diminishes epistemic self-esteem. I conclude by addressing a number of objections that might be marshaled against my argument.

First: one might object to the use of statistical reasoning in credibility assessments of individuals. I assume that if it can be shown that members of a specific social group generally suffer from decreased credibility, then, ceteris paribus, it is justified to ascribe decreased credibility to a particular member of that group, given the right conditions. Applying statistical generalities to individual cases is not necessarily problematic. We use similar reasoning when evaluating medical advice from a random person, assuming they are unlikely to be a physician. Even if they are, no testimonial injustice is done by assigning only moderate credibility to their advice. The belief may be false in that case, but it is not culpably false.

Second: one might object that as empirical research progresses, the assumptions on which this argument rests may, in time, require revision. This concern is well taken. As noted in a footnote, since the first draft of this paper, research on stereotype threat has come under increasing scrutiny. In light of this, I have ensured that the present argument does not rely on it, making the case for self-fulfilling testimonial injustice independent of findings whose robustness has been called into question. However, it cannot be excluded that further revisions may prove necessary as the empirical landscape continues to shift.

Third: one may challenge the scope of the theoretical and empirical findings discussed. One might argue that while these mechanisms can be demonstrated in specific domains of knowledge and expertise, they are not widespread. This objection requires caution. While ongoing research on discrimination and self-fulfilling prophecies (see Bertrand and Duflo, Reference Bertrand and Duflo2017) will provide further insights, the studies referenced here mark the beginning of a broader inquiry.

Fourth: one may be worried about the scale of these mechanisms. Even if self-fulfilling testimonial injustice occurs across various domains, it might be argued that aversive racism is only activated in limited contexts. While this remains an open question, it seems unlikely that self-fulfilling effects would be restricted to a single French grocery store.

Fifth: some may argue that calling self-fulfilling beliefs “true” is a stretch and that they are more akin to false beliefs. However, this view is not necessary. True self-fulfilling beliefs can be supported by evidence, and as the discussed examples illustrate, it can be difficult to recognize that the truth of some credibility assessments is self-fulfilling rather than independent. The supermarket managers, for instance, did not realize this until the economists conducted their research. As long as the underlying mechanism remains unnoticed, what is in fact a self-fulfilling truth appears to be an independent truth.

Sixth: a final objection may question whether the cases discussed actually constitute injustice. It might be argued that, in some cases, the individuals affected bear some responsibility for their underperformance. According to this view, individuals confronted with negative stereotypes should be expected to resist their effects. However, this conclusion is not supported by empirical evidence. The “blame-the-victim” strategy is even more clearly untenable for the other mechanisms discussed. In cases of aversive racism, the minority cashier was entirely unaware of the manager’s bias. In the unemployment case, affected individuals were fully aware of the discrimination they faced – if they were not, it would be difficult to argue that it was rational for them to invest less in knowledge and skills acquisition.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been a long time in the making. Its earliest version was presented over a decade ago, and I have continued to revise it in response to developments in both philosophy and the empirical sciences. My deepest thanks go to Miranda Fricker. The paper grew out of a conversation with her, which, among other things, led to a joint research project on epistemic injustice, funded by the Dutch Research Council (grant 360-20-380) and co-directed by Miranda and myself. That collaboration has remained a lasting source of intellectual stimulation and joy. Over the years, I have had the opportunity to present this paper at a wide range of venues: Aarhus, Cambridge, Groningen, Lugano, Odense, Ottawa, Pamplona, Paris, Princeton, Rotterdam, Sheffield, Tilburg, the Institut für Sozialforschung (Frankfurt), the Joint Session (Warwick), the Society of Applied Philosophy (Copenhagen), the Society of Business Ethics (Atlanta), the OZSW (Utrecht), and a workshop on Political Epistemology (London). I am grateful to the audiences at these events for their thoughtful engagement. For more specific comments and suggestions, I would like to thank Kristoffer Ahlstrom-Vij, Constanze Binder, Anthony Booth, Lisa Bortolotti, Kayleigh Doherty, Elianna Fetterolf, Sanjana Govindarajan, Paul Faulkner, Michael Hannon, Conrad Heilmann (my commentator in Rotterdam), Lisa Herzog, Frank Hindriks, Axel Honneth, Anneli Jefferson, Ian Kidd, Rae Langton, Michele Loi, Nikolaj Nottelmann, Alex Oliver, Barend de Rooij, Jennifer Saul, Tom Simpson, Sophie Strammers, Thomas Teufel, Chris Thompson, Peter Timmerman, Herman Veluwenkamp, Lisa Warenski, Thomas Wells, and Han van Wietmarschen (my commentator in London). I am also indebted to Jennifer Lackey and two anonymous reviewers for Episteme for their incisive comments on an earlier version of the paper. My thanks go as well to Castor Comploj for outstanding research assistance. Some aspects of the language editing were supported by the use of AI-based tools, including DeepL and ChatGPT. Any remaining errors are entirely my own. Research for this paper was supported in part by the Dutch Research Council under grants 360-20-380 and 406.21.FHR.020.