Article contents

Mechanism of malaria transmission in the province of North Holland

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 May 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1938

References

page 62 note 1 See our paper (June 1936) in Quarterly Bulletin Health Organisation, League of Nations, 5, 295–352.Google Scholar

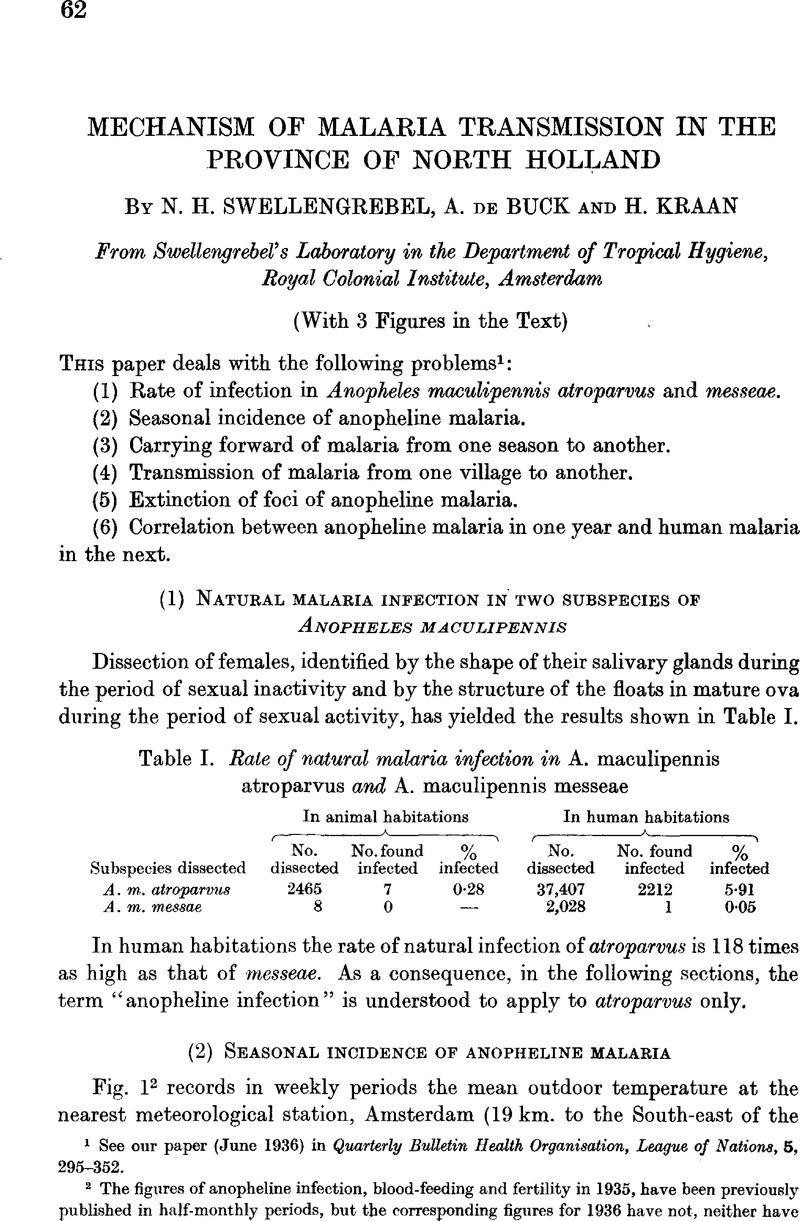

page 62 note 2 The figures of anopheline infection, blood-feeding and fertility in 1935, have been previously published in half-monthly periods, but the corresponding figures for 1936 have not, neither have those relating to temparature and human malaria. The data recorded in Fig. 1 are based on a large table which we omit. We can vouch for the reliability of the anopheline figures as they are based on weekly dissections which averaged 378 in Uitgeest and 198 in other villages. The other figures require no comment.

page 63 note 1 The reason why the infection of Anopheles in Uitgeest is so much lower in 1936 than in 1935, whereas it has decreased but slightly in the other villages, is that the houses were sprayed with insecticides, with the purpose of destroying infected Anopheles.

page 63 note 2 This does not apply to the records of 1935. They are too low in autumn because, in that year, we did not note down the percentage of engorged females on the day following their capture but on the day of dissection. This considerably reduced the number of engorged females, if the mosquitoes captured were too numerous to dissect them all on one day, as often happened in autumn.

page 63 note 3 Swellengrebel, (1929), Ann. Inst. Pasteur, 29, 1370.Google Scholar

page 63 note 4 In 1936 the decline of blood-feeding coincided with a fall in outdoor temperature below 10° C. in the beginning of November. But in 1935 its rise commenced by the end of February, when the outdoor temperature was well under 5° C,

page 67 note 1 Malaria disappeared from this hamlet in 1937, anopheline infection had done so already in 1936. Consequently, the coming and going of malaria entirely depended on family K.

page 68 note 1 It did become extinct in 1937.

page 69 note 1 Swellengrebel, de Buck & Kraan, Roy. Acad. of Science at Amsterdam. Session of 20 March 1937.

page 71 note 1 Two houses with 3 patients and 12 with one patient lying outside the central range of influence have been attributed to that area, because infected anopheles were found in them in 1935. These houses are omitted in Fig. 3.

page 74 note 1 As has also been suggested by van Thiel, (1934), Nederl. Tijdschr. v. Geneesk. 78, 997–1007 (English summary on p. 1007).Google Scholar

- 3

- Cited by