INTRODUCTION

In Italy, as well as in other Western countries, outbreaks of measles continue to occur [1–Reference Chiew4] and the objectives of the National Plan (2003–2007) for measles elimination have not been reached yet in our country [5]. Strategies of the plan include the achievement of more than 95% coverage with one dose of measles vaccine within 2 years of life and two doses within 12 years of life; promotion of measles vaccination to susceptible populations (i.e. adolescents, healthcare and educational workers, military, ‘fragile social groups’ such as immigrants and nomads), and to women of childbearing age (with the objective of reaching a proportion of <5% of susceptibles). In the present study, the incidence of measles in the paediatric and adult populations and its relevant changes over a 14-year period were evaluated to assess the status of measles in Tuscany in relation to the elimination target.

METHODS

Study design and case definition

A retrospective cohort study investigating children (aged <18 years) and adults (aged ⩾18 years) hospitalized for measles from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2014 in 31 Tuscan hospitals was performed.

The regional hospital discharge database was consulted to select the cases, coded according to the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) system [6]. The following ICD-9-CM codes were taken into account: 055·9 (uncomplicated measles), 055·8 (complicated measles), 055·79 (measles associated with specific complications), 055·0 (encephalitis in measles), 055·1 (pneumonia in measles), 055·2 (otitis in measles) and 055·71 (keratoconjunctivitis in measles).

Hospitalized children and adults, living in Tuscany and discharged from a Tuscan hospital with a diagnosis of measles were included in the study. A double-check using any data written up on the enrolled patients was also conducted to avoid possible bias due to the inpatients being transferred between hospitals.

The number of children and adults living in Tuscany, by age group, and surveillance data about vaccination coverage for measles at age 24 months during the study period were provided by the Italian National Statistical Institute database. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Anna Meyer Children's University Hospital in Florence, Italy.

Statistical analysis

The following characteristics of study population were analysed: age, gender, nationality, season of hospitalization of every patient, complications, median length of hospital stay and mode of discharge.

Patients were stratified by six age groups (<1, 1–4, 5–9, 10–17, 18–39, >40 years). Rates of hospitalization for measles were reported as cases/100 000 children and cases/100 000 adults living in Tuscany and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Continuous variables were expressed using median values and interquartile range (IQR) and difference were evaluated using non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test). Categorical variables were analysed using the χ 2 or the χ 2 for trend tests (Cochran–Armitage test for trend). Sensitivity analyses were performed by analysing differences by measles incidence rate associated with age, gender, season of hospitalization, and complications. All significant tests were two-sided. A value of P < 0·05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software package v. 11.5 (SPSS Inc., USA).

RESULTS

During the study period, 181 children and 413 adults were hospitalized for measles by the 31 Tuscan hospitals. Characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population (594 children and adults hospitalized for measles in 2000-2014, in Tuscany)

IQR, Interquartile range.

* Immigrant children's age groups: <1 year: 6/20 (30·0%); 1–4 years: 22/67 (32·8%); 5–9 years: 8/37 (21·6%); 10–17 years 5/57 (8·8%).

Median age in the children subset was 5 (IQR 1–12) years and median age in the adult subset was 29 (IQR 23–36 years). Median age of the entire population included in the study was 23 (IQR 14–32) years. The majority of cases occurred in the 18–39 years age group (57·91%). One quarter of the children cases were immigrants (23·76%), whereas 92·25% of the adult cases were Italian. Median length of hospital stay was 4 (IQR 3–6) days in both the children and adults group.

No death was reported. The most common complications in the children group were pneumonia (14·93%) and dehydration (8·29%), followed by neurological involvement (3·90%) consisting of seizures and encephalopathy (Table 1). Of note, 11/27 (40·7%) cases of pneumonia occurred in the 1–4 years group (6/11 Italians). Neurological complications occurred in the 1–4 and 10–17 years age group.

The most common complications in the adult group were pneumonia (12·35%) and hepatitis (9·44%). Rates of complications in the children and adult groups did not differ between immigrants and Italians.

Measles hospitalization rate in the study population

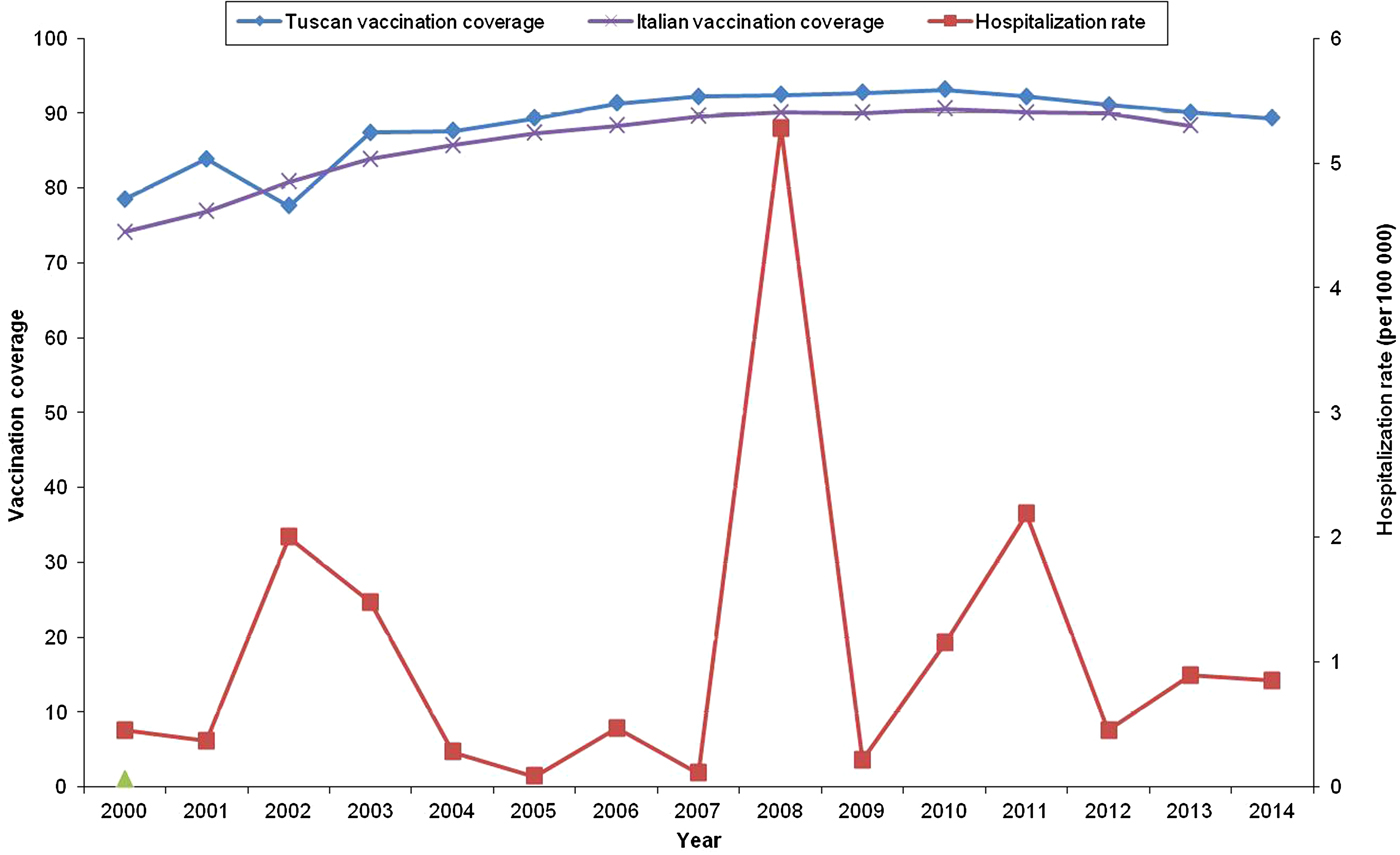

Children aged <1 year presented the highest hospitalization rate (4·38/100 000, 95% CI 2·46–6·30), followed by preschool children (3·67/100 000, 95% CI 2·79–4·55) (Fig. 1). The overall measles hospitalization rates for children and adults living in Tuscany increased over the study period, from 0·45/100 000 in 2000 to 0·85/100 000 in 2014 (χ 2 for trend P = 0·001). Moreover, fluctuations due to periodic measles outbreaks occurred in 2002, 2008 and 2011 (Fig. 2). During the same period, the average vaccination coverage for measles at age 24 months in Tuscany gradually increased from 78·5% in 2000 to a maximum value of 93·1% in 2010 (χ 2 for trend P<0·001), then decreased to 89·3% in 2014 (χ 2 for trend P < 0·001) (Fig. 2). Data stratified by age showed that over the study period the hospitalization rate significantly increased in the 18–39 years age group (χ 2 for trend P < 0·001). Conversely, no statistically significant difference was observed in the hospitalization rate in the other age groups.

Fig. 1. Hospitalization rate (per 100 000) for measles in Tuscany over the study period (2000–2014), stratified by age group.

Fig. 2. Hospitalization rate (per 100 000) and vaccination coverage (%) for measles in Tuscany and in Italy over the study period (2000–2014).

DISCUSSION

The present report analyses changes in measles hospitalization rates in the paediatric and adult populations in Tuscany over a 14-year period, using regional discharge data.

Despite all the efforts towards regional measles elimination [5], we observed that the overall measles hospitalization rates for children and adults living in Tuscany globally increased from 0·45 to 0·85/100 000 during the study period, showing fluctuations due to periodic measles outbreaks. These findings are not completely unexpected since an optimal vaccination coverage has not yet been achieved: average vaccination coverage for measles at age 24 months in Tuscany was 89·3% in 2014, not reaching the measles control goal of >90–95%. Moreover, this value which is an expression of a progressive decrease in vaccination coverage was noted in the last years, leading to silent increasing of susceptible subjects [Reference Del Fava7]. This phenomenon could be partly related to growing concerns regarding the safety of vaccines, encouraged by anti-vaccination movements that are spreading in European countries, and underlines the importance of strongly reinforcing public awareness on the safety and efficacy of measles vaccine [Reference Zahn8]. In a recent cross-sectional study conducted in Italy, the role played by the internet [odds ratio (OR) 19·8, P = 0·001] and the large number of children in a family (OR 7·3, P⩽0·001) were the factors more associated with being unvaccinated [Reference Restivo9]. Some authors have suggested a suboptimal vaccination coverage in migrant populations may be related to language, information and administrative barriers in accessing routine immunization and health services for these vulnerable subjects [Reference Williams10], but in our study only one quarter of paediatric cases was in immigrant children and the complication rate did not differ between Italians and immigrants. This confirms what we expected, as vaccinations in Tuscany (as in Italy) are offered for free to all residents. However, considering that our study is based on a regional electronic database, we do not have sufficient and detailed information regarding the nationality of the parents to evaluate differences between Italians and ‘second-generation’ immigrant children.

Our data confirm that large measles epidemics continue to occur in Italy, although differences between regions have been described [Reference Filia11, Reference Filia12]. These discrepancies can be explained not only by differences in current regional measles-mumps-rubella vaccination coverage levels [13], but also by underreporting, especially in southern regions [Reference Filia11, Reference Filia12]. Recently measles has re-emerged in other European countries which experienced large outbreaks in the same years as observed in Tuscany [1]. In the United States a record number of 668 measles cases from 27 states was reported to CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) in 2014, which was the greatest number of cases since measles elimination was documented in the United States in 2000 [2].

Our data, described in Table 2, show that the hospitalization rate significantly increased in young adults over the study period, confirming an increase in susceptibility to measles [Reference Chiew4, Reference Bechini14–Reference Pezzotti17]. Considering that globally measles incidence is usually expressed as cases per million population (with a goal of <5 cases/million by 2015), rates of hospitalized measles cases (2·19/100 000 = 22/million) are quite high and suggest high rates of transmission in the community, indicating that this is just the tip of the iceberg. In fact the current immunization programme has left a window of vulnerability for young adults who have never been exposed to measles, have never been vaccinated or were vaccinated but did not respond. Moreover, it must be considered that vaccine-induced immunity may decline over time. It has been described that subjects who received their last dose of measles vaccine more than 10 years previously have a small but significantly increased risk of becoming infected compared to people recently vaccinated, suggesting that measles vaccination does not guarantee a lifelong immunity [1, Reference Jones18]. Additionally, it should be taken into account that the role of ‘natural boosting’ is declining [Reference Del Fava7, Reference Bechini19]. Del Fava and colleagues, in their study conducted with the aim of analysing the effects of a large vaccination campaign in Tuscany, accurately identified a large pocket of susceptible individuals aged about 13–14 years in 2005–2006, and a larger group of weakly immune individuals aged ~20 years in 2005–2006. These authors concluded that these cohorts represent possible targets for further interventions towards measles elimination [Reference Del Fava7].

Table 2. Yearly absolute number of cases and hospitalization rate/100 000 for measles (95% CI) by age group in Tuscan children and adults, 2000–2014

CI, Confidence interval.

Low vaccination coverage in healthcare workers (HCWs) may have contributed to the spread of measles in healthcare settings during the outbreaks, as previously reported in Italy [Reference Campagna20, Reference Porru21]. Interestingly, in a recent cross-sectional survey performed in six Florentine hospitals, among those HCWs reporting no history of disease, 52·8% declared having been immunized against measles, and when considering potentially susceptible HCWs (without history of disease or vaccination and without serological confirmation), less than half of them felt at risk for the concerned diseases and only <30% would undergo immunization. Lack of an active offer of vaccines was considered to be one of the main reasons of the relatively low coverage [Reference Taddei22]. Unfortunately, no data about nosocomial transmission cases were available in our database to allow us to analyse this mode of transmission.

As in other Western countries [1, Reference Chiew4, Reference Pezzotti17], children aged <1 year presented the highest hospitalization rate. This is possibly related to the actual vaccination policy (the first measles vaccine dose is administered at age 12 months), but also to the high susceptibility of adult contacts which may constitute an important reservoir for transmission. Moreover, the weaning immunity in women of childbearing age does not allow the indirect protection of infants through maternal antibodies transferred across the placenta. Although immunization programmes have led to a marked reduction in measles complication rates, still pneumonia represents the main complication in both children and adults, as reported above [23–Reference Hamborsky, Kroger and Wolfe25].

Our study may have some limitations. Although the ICD-9 discharge diagnosis code is an accurate method to monitor the occurrence of some diseases [Reference Meregaglia26–Reference Bonsignori30], some diagnoses may have been inadvertently excluded or misattributed. However, it is unlikely that this possible bias changed our final results.

Another limitation of our study is represented by the challenge to estimate the actual incidence rates of the disease, as we could only analyse hospitalization data. Excluding cases of mild measles that did not require hospital care may have led to a slight overestimation of complication incidence, and to an underestimation of measles incidence rates. The Italian National Surveillance System does not register the vaccination coverage after the second dose of vaccination (which is recommended at 5–6 years), so we were unable to analyse the actual adherence to the vaccination schedule over time. Additionally, in our analysis we could not consider the vaccination status of each case included, as these data were not available. These kind of information would have been helpful to evaluate the waning immunity in adolescents and young adults, and to compare the risk of complicated disease in unvaccinated and vaccinated subjects. Moreover, we considered anyone born in Italy as ‘Italian’, regardless of immigration status of parents. It would have been interesting to evaluate hypothetical differences between Italian and ‘second-generation’ immigrant children but we did not have sufficient and detailed information regarding the nationality of the parents of the cases reported in our regional database.

CONCLUSIONS

Measles still represents a serious public health problem worldwide [1–Reference Chiew4], highlighting that the current approach is not effective in interrupting the circulation of the virus. Although the Tuscan region has always represented excellence in the field of prevention in Italy, in our analysis we evidenced a marked decline in immunization coverage rates in the last years, leading to new outbreaks of measles in this area, as in the rest of Italy and Europe. High vaccination coverage (⩾95%) with two doses of measles vaccine in all population groups is crucial to elimination. Vaccination coverage, even for a second dose, should be improved with tailored strategies, especially with respect to young adults and adolescents, with special consideration for women of childbearing age. Every opportunity should be used to reach children with routine vaccination and to present adolescents and adults with the option of checking their vaccination status and receiving vaccinations that they may have missed.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.