1. Introduction

Between 2000 and 2019, more than 7,000 disasters affected about 4.2 billion individuals worldwide. Remarkably, developing nations in the Asian region constitute about 40 per cent of the total global disaster-related damages and 90 per cent of the victims worldwide (Guha-Sapir et al., Reference Guha-Sapir, Hoyois, Wallemacq and Below2017; Mizutori and Guha-Sapir, Reference Mizutori and Guha-Sapir2020). The repercussions of these shocks range from short-term setbacks to long-term impediments to growth and development (Caruso and Miller, Reference Caruso and Miller2015). The affected populations often experience significant economic disruptions, resulting in infrastructural and property damage and loss of livelihoods (Zeleňáková et al., Reference Zeleňáková, Gaňová, Purcz, Horský, Satrapa, Blišt'an and Diaconu2017; Boustan et al., Reference Boustan, Kahn, Rhode and Yanguas2020).

In settings where natural disasters impede capital accumulation and day-to-day activities, the resilience of labor markets is critical for poor individuals who depend on labor to mitigate risks associated with environmental shocks (Mueller and Quisumbing, Reference Mueller and Quisumbing2011). Short-term economic losses from natural disasters may affect the ability to participate in the labor market and contribute to long-term poverty (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Dietz, Yang, Zhang and Liu2018). Disasters result in poverty-environment traps that further exacerbate the economic well-being of poor communities (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Little, Mogues and Negatu2007; Van den Berg, Reference Van den Berg2010; Haider et al., Reference Haider, Boonstra, Peterson and Schlüter2018). On the other hand, disasters can offer opportunities for growth in reinvestment and capital upgrades, helping communities replace destroyed capital with new technologies (Gignoux and Menéndez, Reference Gignoux and Menéndez2016) and reallocate labor supply (Deryugina et al., Reference Deryugina, Kawano and Levitt2018).

This article examines the impact of severe floods on agricultural labor wages paid in cash and in-kind. Nepal experienced the heaviest rainfall from August 11 to 14 in 2017, inundating about 80 per cent of the land in the southern part of the country. During this period, moderate to severe levels of flooding engulfed almost one-third of districts in the entire country. The 2017 floods affected more than 15,000 houses, causing damages to household assets and shortages of food, water, and non-food items (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Zhang, Koju, Zhang, Bai and Suwal2019). In an agricultural labor market setting, total wages comprise cash and in-kind wages. Because employers in several developing and least-developed economies offer cash wages, in-kind wages, or a mix of both types of wages (Tijdens and Van Klaveren, Reference Tijdens and Van Klaveren2011), we examine how the 2017 floods in Nepal affected cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers. We hypothesize that a resource crunch can cause cash wages to decline immediately after floods, and in-kind wages can serve as compensating mechanisms that help agricultural laborers mitigate the negative impact of floods on cash wages to maintain household utility.

Using a two-way fixed effects estimation setup, we exploit the incidence of the 2017 floods to evaluate the repercussions on cash and in-kind wages in flood-affected districts. Within our empirical framework, we utilize panel data on cash and in-kind wages from three rounds of household surveys conducted by the World Bank in 2016, 2017, and 2018. This allows us to examine wage changes between districts affected by the floods and those unaffected before and after the 2017 floods. Our empirical model incorporates fixed effects at the village and district levels to control for time-invariant unobservable factors influencing wage-related outcomes while addressing month-by-year specific unobservable shocks in agricultural labor markets. Additionally, we estimate dynamic treatment effects associated with the 2017 floods and present findings through an event study research design. We further delve into the underlying mechanisms, exploring potential channels through which the observed effects manifest. We investigate the impact of floods on labor supply at the extensive margin, alterations in financial assistance, loan-seeking behavior, and loan repayment schedules to examine possible channels that could have caused the effect on wages. Lastly, we explore heterogeneity in treatment effects across gender, religion, and caste categories.

Our findings reveal that the 2017 floods resulted in a reduction in cash wages for agricultural laborers. However, we also observe an increase in in-kind wages, serving as risk-mitigating mechanisms. Our two-way fixed effects estimates illustrate that the 2017 floods led to a 9–10 per cent decrease in daily cash wages for agricultural households. Additionally, our results indicate that the total income from in-kind compensation for agricultural laborers increased approximately 1.5 times a year after the floods. The event study specification suggests that the decline in cash wages and the rise in in-kind support persisted for about a year. We further note that the severity of flood damages led to a significant impact on labor market outcomes, while we find limited evidence of spillover effects to unaffected neighboring districts.

In relation to possible mechanisms, we begin with an exploration of a shift in labor supply through which floods can affect wages in our setting. However, we do not find statistically significant effects on labor supply following the flood event. We also examine changes in financial assistance to assess the impact of floods on economic recovery. While there is no significant effect on cash assistance, we find a notable reduction in in-kind assistance after the incidence of the floods. Additionally, we investigate whether cash-strapped households seek more loans, which leads us to document a significant increase in household debt. However, we do not find any significant effect on debt repayment. Concurrently, we show that the likelihood of households taking loans for house repair, home purchase, livestock purchase, health expenditure, and agricultural input purchase increased, strengthening our hypothesis of a cash crunch in the local economy in the aftermath of floods.

These results illustrate that the 2017 floods caused economic disruptions that, in turn, decreased cash wages and induced employers to compensate agricultural laborers with an alternative means of payment in the form of in-kind wages. Our findings conclude that rural households in agricultural economies rely on barter systems to maintain household utility when cash is not readily available. We also rule out the channel of a shift in labor supply that may cause changes in the equilibrium wages of laborers. While we focus on the short-term impact on wages, we leave the long-term effect of floods on the resilience of agricultural labor markets for future research.

Although prior literature has focused on changes in cash wages in response to environmental shocks (Mueller and Quisumbing, Reference Mueller and Quisumbing2011; Kirchberger, Reference Kirchberger2017; Branco and Féres, Reference Branco and Féres2021), we know relatively little about the mitigating mechanism farmers use in the form of in-kind wages to compensate for disaster-induced economic losses. As such, our study contributes to the literature in three specific ways. First, we estimate changes in cash wages and income from in-kind wages in response to large floods in a developing country setting. To the best of our knowledge, we provide the first evidence on whether agricultural laborers rely on in-kind wages to partially mitigate the adverse effects of floods on cash wages. Due to flood-induced shocks in the economy, both wages move in opposite directions as farmers use these wages as substitutes for each other. For the same amount of work, a reduction in cash wages is associated with an increase in in-kind wages to maintain their income levels. Second, we contribute to existing work on whether environmental shocks exacerbate disparities in labor market outcomes across categories related to gender, caste, and religion. For example, we find that male laborers in flood-affected districts experienced a 7.4 per cent decline in agricultural cash wages. In contrast, female workers saw a much more significant decline of 16.7 per cent in cash wages, implying that floods can worsen labor market disparities between male and female workers. Finally, we provide estimates of labor market spillovers associated with the incidence of floods in neighboring districts.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed background on the 2017 floods in the Terai region and section 3 briefly summarizes the literature on the economic effects of natural disasters. Section 4 outlines the data utilized in our study followed by a discussion on the research design in section 5. Section 6 reports our main findings on the estimated impact of floods on wages. Section 7 presents findings on flood-induced changes in labor supply on extensive margin, financial assistance, loan seeking behavior, and loan repayment schedules. Section 8 evaluates possible spillovers and heterogeneous treatment effects across categories related to gender, caste, and religion. Section 9 provides concluding remarks with a brief discussion on policy implications.

2. Background

Nepal is a land-locked country with a total area of 56,956 square miles, surrounded by India on three sides and China to the north. Figure 1 presents a geographical map of Nepal that comprises seven provinces and 77 districts with an average population density of about 540 people per square mile of land area in 2021.Footnote 1 Geographically, the country consists of three central ecological regions: the Mountains, Hills, and Terai. The Terai region, characterized by its lowlands, constitutes approximately 17 per cent of Nepal's total land area and spans 21 districts. Notably, over 53 per cent of the country's population resides in the Terai region, rendering it one of the most densely populated areas. The Terai region is heavily dependent on agriculture for livelihood and food security.

Figure 1. Geographical variation in the incidence of 2017 floods in Nepal.

The Terai region features exceptionally rich soil that significantly influences the agricultural sector. The region consists of dark brown topsoil over a light yellow or brown loamy subsoil most suitable for growing crops, vegetables, and other food items (Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Bhattarai and Aryal2016). Consequently, the agricultural-based economy in the Terai region has led to significant developments in irrigation facilities, roads, and market infrastructure (Biswas, Reference Biswas1989). The region is suitable for growing rice and other crops, including wheat, chickpeas, lentils, oil seeds, mustard, sugarcane, mangoes, and litchis. Farmers in the Terai region tend to be progressive and are invested in applying acquired knowledge and building effective strategies for improving annual yields, agricultural productivity, and income. Some of their strategies include adopting new technologies and production practices and improving access to input and output markets.

The Terai region is home to large rivers, such as the Koshi, Gandaki, and Karnali, which comprise 19 smaller tributaries. This confluence of water bodies contributes to the region's exceptional fertility and is pivotal in its agricultural prosperity. However, this very characteristic also renders the region highly susceptible to floods. Over the past few decades, Nepal has witnessed a series of catastrophic floods in the Terai region, especially during the monsoon season. Monsoons bring more than 80 per cent of Nepal's annual rainfall, leading to heightened river water levels and elevated risks of severe flooding.

The interplay between the major rivers and their tributaries in the Terai region is worth highlighting. On one hand, the soil around the rivers is highly fertile, providing a significant boost to the economy and livelihoods through agriculture. On the other hand, seasonal floods caused by heavy rainfall pose a significant challenge to the communities living along the river. This vulnerability underscores the need for effective flood management and disaster preparedness measures in the region.

During 11–14 August in 2017, 24 out of 77 districts in Nepal observed one of the most severe floods in recent times. Of the 24 affected districts, 18 were severely affected, while six were moderately affected. The districts that were severely affected include Kailali, Banke, Dang, Nawalparasi, Chitwan, Makwanpur, Parsa, Bara, Sarlahi, Mahottari, Dhanusha, Saptari, Sunsari, Jhapa, Morang, Rautahat, Bardiya, and Siraha. The moderately-affected districts include Surkhet, Kapilavastu, Palpa, Rupandehi, Udayapur, and Sindhuli. The 2017 floods displaced more than 1.7 million people, with about 130 deaths reported in severely affected districts.Footnote 2

3. Review of relevant literature

This article contributes to three streams of literature. First, it adds to the growing literature on the effects of natural disasters on agricultural productivity and labor markets. Second, it contributes to an influx of studies that discuss mitigating strategies in the agricultural sector. Third, it contributes to the research on the significance of in-kind wages as one of the key risk-hedging strategies in unorganized labor markets in the agricultural sector.

Extreme climatic changes are more frequent than ever, causing an increase in the incidence of floods, droughts, hurricanes, rising sea levels, heat waves, cold waves, and earthquakes. The effects of natural disasters on human capital and labor market outcomes have been studied extensively (Caruso and Miller, Reference Caruso and Miller2015; Groppo and Kraehnert, Reference Groppo and Kraehnert2017; Pajaron and Vasquez, Reference Pajaron and Vasquez2020; Shakya et al., Reference Shakya, Basnet and Paudel2022; Andrabi et al., Reference Andrabi, Daniels and Das2023; Khanna and Kochhar, Reference Khanna and Kochhar2023; Paudel, Reference Paudel2023). Floods can have short-term and long-term effects on agricultural productivity depending on the severity of the flood intensity and the type of crops (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2010). A recent study using high-quality geographic information system (GIS) data on vegetation finds that severe drought and extreme floods cause a significant decline in agricultural productivity (Blanc and Noy, Reference Blanc and Noy2023). Such a negative impact on agricultural productivity can cause severe concerns for household food security (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Anderson, Kruczkiewicz, Nakamura, Gallo, Seager and McDermid2022).

An influx of studies suggests that floods cause wages in the agricultural sector to decline both in the short and long term (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2007; Mueller and Quisumbing, Reference Mueller and Quisumbing2011). For example, Jayachandran (Reference Jayachandran2006) finds that agricultural productivity shocks in India adversely affect wages among poorer individuals, hindering their ability to migrate and further constraining credit from inelastic labor supply. The reduction in agricultural productivity drives these adverse effects. Other studies in emerging nations conclude that wages could have a positive effect due to an increase in non-agricultural employment after the incidence of floods (Parida and Chowdhury, Reference Parida and Chowdhury2021).

It is well-documented that farmers employ several mitigating strategies in the aftermath of climatic shocks such as floods. For example, traditional methods of farmers’ adaptation to climate change and extreme weather include using different crop varieties, planting trees, soil conservation, early and late planting, adopting new technologies, and improved irrigation methods (Deressa et al., Reference Deressa, Hassan, Ringler, Alemu and Yesuf2009). Farmers adjust their operational land size through rental mechanisms to compensate for partial losses from flood damage (Eskander and Barbier, Reference Eskander and Barbier2023). In a different study, Deressa et al. (Reference Deressa, Hassan, Ringler, Alemu and Yesuf2009) shows that rainfall shocks in Brazil result in a lower share of agricultural employment and induce farming households to increase labor supply in non-agricultural sectors. Overall, changes in labor decisions could help agricultural households mitigate the impact of weather shocks.

Post-flood economic development and governance may have an important role in mitigating flood-induced damages (Parida, Reference Parida2020). Many countries have implemented food-for-work programs that offer wages in food grains to ensure food security (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Holden and Clay2002; Bezu and Holden, Reference Bezu and Holden2008). With increased agricultural production over the last few decades, economies have slowly moved from barter systems to cash payments for products and services. Still, in-kind wages are prevalent in developing nations, given that food security is a prime consideration in settings characterized by poverty and uncertain food markets (Kurosaki, Reference Kurosaki2008). These in-kind wages can take different forms, such as grains, clothes, meals, and other types of goods that rural households can substitute for cash. Research indicates that markets reach an optimum mix between cash and in-kind wages that can act as risk-hedging instruments and improve overall welfare. The optimum mix varies based on the price conversion of in-kind wages to match cash wages (Datta et al., Reference Datta, Nugent and Tishler2004). Policymakers consider in-kind transfers efficient alternatives to cash transfers, sometimes resulting in additional consumer benefits (Currie and Gahvari, Reference Currie and Gahvari2008; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, De Giorgi and Jayachandran2019). We are, therefore, interested in examining whether farmers use these in-kind wages to partially mitigate undesirable environmental shocks and continue to maintain their initial utility levels.

4. Data

This research uses wage data from the nationally representative Household Risk and Vulnerability Survey in Nepal by the World Bank. This survey was conducted in three rounds in consecutive years: 2016, 2017, and 2018. It covers 6,000 households and 400 communities in non-metropolitan areas of Nepal in 50 out of 75 districts.Footnote 3 The survey covers a range of topics including education, health, access to facilities, food security, labor supply, agricultural activities, migration, financial security, and public assistance.

These surveys were conducted in June-July-August of 2016, June-July-August-October of 2017, and June-July-August-September of 2018. Using this information, we create a monthly panel with 11 periods. Since the flood happened in August 2017, we have had access to six post-treatment periods and five pre-treatment periods. Individual households were interviewed only once a year, causing our monthly panel data to be unbalanced in our empirical analysis.

Our primary outcome variables include the log of cash wages and in-kind wages. The unit of cash wages is Nepalese Rupees (NPR) per day. We also note that the unit of in-kind wages is NPR, which means that the in-kind wages are observed as total income in the form of in-kind. Table 1 shows the summary statistics in the pre-treatment period. Columns (1) and (2) present a summary of observable characteristics in flood-affected districts and control districts, respectively. Column (3) presents the differences in means of these characteristics between these two types of districts. The average cash and in-kind wages are slightly higher in the control group. The sample proportion of males is about 48 per cent in flood-affected districts, which is 1 percentage point higher than in the control districts. The age distribution in the control and treatment groups is almost similar. Since the economy of the Terai region is agriculturally intensive, more individuals depend on agriculture for employment in this region compared to control districts. Hence, the proportion of laborers among the total employed is higher in the flood-affected Terai region compared with the Hills and Mountains. We further plot trends in cash and in-kind wages in figures 2a,b. To account for the possibility that our parallel trend graphs may suffer from non-continuous periods before the incidence of the floods, we perform additional robustness checks in section 6 to discuss the comparability of our control and treated units.

Table 1. Summary statistics of flood-affected and flood-free districts before August 2017

Figure 2. Trends in cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers with vertical lines denoting the flood shock. (a) Cash wages, (b) In-kind wages.

5. Empirical strategy

In this section, we outline our empirical approach to determine the impact of floods on both cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers in Nepal. We focus on comparing wages between flood-affected districts and their unaffected counterparts before and after the incidence of the floods.

Let $Y_{i,d,t}$![]() be the outcome variable for an individual $i \in \lbrace 1,\ldots,N\rbrace$

be the outcome variable for an individual $i \in \lbrace 1,\ldots,N\rbrace$![]() in district $d \in \lbrace 1,\ldots,k\rbrace$

in district $d \in \lbrace 1,\ldots,k\rbrace$![]() during period $t \in \lbrace Jun'2016,\ldots, Sep'2018 \rbrace$

during period $t \in \lbrace Jun'2016,\ldots, Sep'2018 \rbrace$![]() . The 2017 floods affected nearly half of the districts in the Terai region in August 2017, which we consider the starting point of our treatment definition. To estimate the average treatment effect of the flood on wages, we employ a two-way fixed effects regression model,

. The 2017 floods affected nearly half of the districts in the Terai region in August 2017, which we consider the starting point of our treatment definition. To estimate the average treatment effect of the flood on wages, we employ a two-way fixed effects regression model,

where $flood_{d,t}$![]() is a binary treatment variable that takes a value of 1 for a district $d$

is a binary treatment variable that takes a value of 1 for a district $d$![]() affected by the flood in August 2017 and thereafter. This setup allows us to estimate the difference-in-differences research design where districts unaffected by the 2017 floods serve as controls for the flood-affected districts. We conduct separate estimations using equation (1) for cash wages and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers. If the flood impacted wages, we expect a statistically significant value for $\beta ^{flood}$

affected by the flood in August 2017 and thereafter. This setup allows us to estimate the difference-in-differences research design where districts unaffected by the 2017 floods serve as controls for the flood-affected districts. We conduct separate estimations using equation (1) for cash wages and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers. If the flood impacted wages, we expect a statistically significant value for $\beta ^{flood}$![]() . Our hypothesis is that cash wages may have been negatively affected, but laborers might have been compensated for this loss through in-kind wages. Given that the treatment allocation occurs within districts, we report the heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors using (Conley, Reference Conley1999) with a spatial distance cutoff of 50 km.

. Our hypothesis is that cash wages may have been negatively affected, but laborers might have been compensated for this loss through in-kind wages. Given that the treatment allocation occurs within districts, we report the heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors using (Conley, Reference Conley1999) with a spatial distance cutoff of 50 km.

We modify our equation (1) to calculate the dynamic treatment effect of the floods and plot event study estimates as

where $flood_d$![]() is a binary variable equal to 1 for flood-affected districts. We include individual fixed effects $\alpha _i$

is a binary variable equal to 1 for flood-affected districts. We include individual fixed effects $\alpha _i$![]() and district fixed effects $\delta _d$

and district fixed effects $\delta _d$![]() to control for time-invariant unobservables and month-year indicators $\lambda _t$

to control for time-invariant unobservables and month-year indicators $\lambda _t$![]() to control for common time shocks. This specification estimates pre-trends for the periods before the intervention and the dynamic treatment effects $\beta _{\ell }$

to control for common time shocks. This specification estimates pre-trends for the periods before the intervention and the dynamic treatment effects $\beta _{\ell }$![]() . Following Borusyak and Jaravel (Reference Borusyak and Jaravel2018), we omit the indicator for July 2017 which is the final pre-treatment period as the base period. We note that estimating equation (2) via ordinary least squares with high dimensional fixed effects such as month-by-year fixed effects, household fixed effects, village fixed effects, and district fixed effects yields an unbiased estimate of the dynamic average treatment effect on the treated under standard parallel trends, no spillovers, and strict exogeneity assumptions.

. Following Borusyak and Jaravel (Reference Borusyak and Jaravel2018), we omit the indicator for July 2017 which is the final pre-treatment period as the base period. We note that estimating equation (2) via ordinary least squares with high dimensional fixed effects such as month-by-year fixed effects, household fixed effects, village fixed effects, and district fixed effects yields an unbiased estimate of the dynamic average treatment effect on the treated under standard parallel trends, no spillovers, and strict exogeneity assumptions.

6. Impact of floods on wages

6.1 Main specification

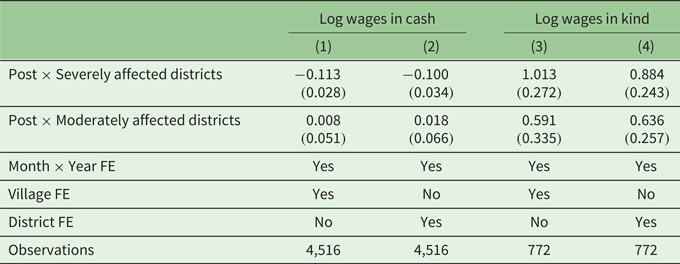

Table 2 shows that the 2017 floods led to a strong and significant impact on cash wages (NPR per day) and in-kind wages (NPR) of agricultural laborers in Nepal. In columns (1) and (2), we show that the floods caused a 9–10 per cent decline in cash wages in flood-affected districts. On the other hand, columns (3) and (4) indicate that compensation in the form of in-kind wages of laborers increased significantly in the aftermath of the floods, with slope coefficient estimates ranging between 0.8–0.9. These findings align with anecdotal evidence that rural economies in least-developed countries still practice a barter system in the agricultural labor market when cash is not readily available. This hedging mechanism incentivizes laborers to be more productive, which, in turn, helps them get paid through grains and other means.

Table 2. Impact of 2017 floods on cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers in Nepal

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1). Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

We also evaluate the dynamic impact of the 2017 floods on cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers using an event study specification outlined in equation (2). Figures 3a,b plot the coefficients and the corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals estimated from the event study regression on two variables of interest: cash wages and in-kind wages. We note three observations from the event study approach. First, it is reassuring to see that the majority of the pre-treatment estimates in relation to both cash and in-kind wages do not display statistical significance before July 2017. This indicates that we do not observe any pre-trends before the incidence of the 2017 floods. Second, we observe a consistent decline in cash wages after the floods throughout the entire post-treatment period in figure 3a. Finally, we note that although floods led to a positive increase in in-kind wages in figure 3b, the statistically significant effects appear to be prominent during a year after the floods.

Figure 3. This figure presents two-way fixed effects event-study estimates from equation (2) with 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered at the district level.

A closer examination of the trends in the aftermath of the flood event allows us to discern clear patterns in cash and in-kind wages. Specifically, we find a noticeable decline in cash wages after August 2017, which serves as evidence of the dynamic impact of the flood event on the local economy. In contrast, we observe an uptick in in-kind wages during this period. These findings support the hypothesis that the incidence of floods can significantly influence the earnings of agricultural laborers.

We attribute the reduction in cash wages to the economic disruptions caused by the floods. This disruption, in turn, hindered cash circulation within the system, ultimately affecting the compensation provided in the form of cash. This decrease reflects the challenges of accessing and utilizing physical currency faced by both employers and employees during the post-flood period in Nepal.

Conversely, we believe that the increase in in-kind wages is a response to the disruptions in the supply chain and the limited availability of cash in the system. Employers, confronted with difficulties in obtaining and disbursing cash, chose to compensate their workers with goods and services instead of traditional currencies. This shift in compensation methods demonstrates how employers adapt with a pragmatic approach to ensure timely remuneration for employees in the face of economic challenges.

6.2 Effect on wages due to intensity of flood

We further test whether flood-induced changes in wages are driven mostly by the severity of floods. As such, we construct binary indicators of districts that were severely and moderately affected by the floods. These categories are defined by the National Planning Commission of Nepal in its flood assessment report based on the number of deaths and injuries.Footnote 4 Our modified equation (1) is

where $Severe Flood_{d,t}$![]() and $Moderate Flood_{d,t}$

and $Moderate Flood_{d,t}$![]() are binary indicators of flood intensity: districts severely affected by the floods and those moderately affected by the floods, respectively. The rest of the variables are the same as in equation (1). To the extent that the severity of floods causes economic disruptions, we expect $\beta ^{severe}$

are binary indicators of flood intensity: districts severely affected by the floods and those moderately affected by the floods, respectively. The rest of the variables are the same as in equation (1). To the extent that the severity of floods causes economic disruptions, we expect $\beta ^{severe}$![]() to be negative and statistically significant.

to be negative and statistically significant.

Table 3 shows that flood-induced wage changes are statistically significant in severely affected districts. In columns (1) and (2), we observe that cash wages declined by 10–11 per cent, while in columns (3) and (4), we find that in-kind wages increased between 1.4–1.7 times in severely affected districts in the aftermath of the floods. In moderately affected districts, the effect on cash wages was not statistically significant, but in-kind wages increased by about 0.8 times. These findings conclude that most of the effects of flooding on wages are driven by severely affected districts. From a policy perspective, our results illustrate that policymakers need to prioritize severely affected districts for interventions designed to mitigate the effects of flooding on the labor market outcomes of agricultural laborers.

Table 3. Impact of 2017 floods on cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers in severely affected and moderately affected districts

This table presents DID estimates from equation (3) in which we construct binary indicators of districts that are severely and moderately affected by floods. These categories are defined by the National Planning Commission of Nepal in their flood assessment report based on the number of deaths and injuries. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

7. Mechanisms

7.1 Effect on financial assistance

It is well-known that when natural disasters occur, many governments, as well as non-government organizations, provide financial assistance to help the victims get back on their feet quickly. There exists an influx of studies that explore the degree to which aid can mitigate disaster-induced changes in economic outcomes in the South Asian setting (Andrabi and Das, Reference Andrabi and Das2017; Eichenauer et al., Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs, Kunze and Strobl2020). Based on prior literature, we hypothesize that aid in cash (in-kind) form can help boost the labor market quickly through payment in the form of cash (in-kind) wages. This allows us to test whether the incidence of the 2017 floods led to any changes in financial assistance.

Because the World Bank Household Risk and Vulnerability Survey collects information on cash and in-kind assistance received by households, we further analyze if there were any significant changes in the assistance inflows after the incidence of the floods. Estimates from table 4 illustrate that the assistance in kind decreased by about 53,000 NPR, while the coefficient for in-cash assistance is negative and statistically insignificant. This finding is not entirely surprising given that a large portion of disaster aid commitments in Nepal goes to areas dominated by high castes while depriving individuals in need who live farther away from urban areas (Eichenauer et al., Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs, Kunze and Strobl2020; Paudel, Reference Paudel2021).

Table 4. Impact of 2017 floods on cash and in-kind assistance

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1). Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

7.2 Effect on loan-seeking behavior

We believe that if floods result in a reduction in household utility and financial assistance, the natural mechanism for households to rely on involves the possibility of loans from commercial banks. This led us to further analyze the information on household debt. In table 5, we present the estimated impact of the 2017 floods on the amount of household debt and the likelihood of a loan for house repair, house purchase, livestock purchase, healthcare expense, and input purchase. In column 1, we find that, on average, households affected by the flood took about Rs. 16,000 loans post-shock compared to the households in the control group. In column 2, we find that the log-likelihood of taking a loan for home repairs increased by 0.28. Similarly, the log-likelihood of a loan for a home purchase increased by 0.8, the purchase of livestock increased by 0.53, health expenses increased by 0.28, and the purchase of inputs increased by 0.28. These results indicate that flood-affected districts were severely cash-strapped after the incidence of the 2017 floods.

Table 5. Impact of 2017 floods on loan-seeking behavior

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1). Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

7.3 Effect on loan repayment and collection

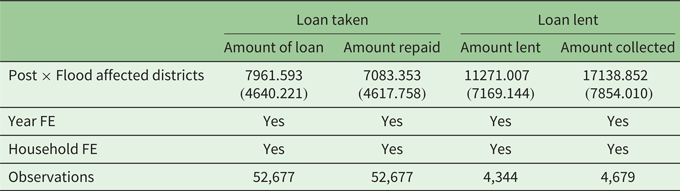

In the preceding section, we observed a surge in the propensity to seek loans in the aftermath of the 2017 floods. This motivated us to delve deeper into analyzing loan repayment and collection behavior. Our investigation reveals that, despite a rise in the number of loans acquired by individuals, there was no corresponding alteration in the lending activities of individuals. Contrarily, we do not identify any noteworthy impact on the repayment of loans. This implies that the financial system in a flood-affected region, grappling with a shortage of cash, has led to an escalated demand for cash and an increased dependence on debt instruments (table 6).

Table 6. Impact of 2017 floods on loan repayment

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1). Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

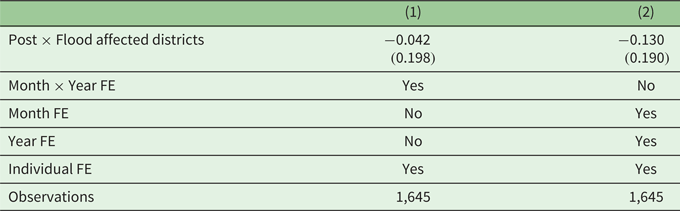

7.4 Effect on agricultural labor supply on extensive margin

We also delve into possible changes in labor supply on extensive margins in the agricultural sector after the incidence of the floods. To the extent that floods cause a major shift in labor supply, it is possible that equilibrium wages will change as well. In fact, we find that the likelihood of being involved with agricultural labor is not statistically different between flood-affected districts and unaffected counterparts while accounting for individual, month-by-year, year, and month-fixed effects as presented in table 7. This provides strong evidence that a shift in labor supply post-flood shock is unlikely to affect equilibrium wages in our setting. This finding is also consistent with our main hypothesis that labor wages may not have changed but the composition of wages likely altered after the incidence of the floods.

Table 7. Log odds of being agricultural labor

Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

8. Heterogeneity and spillover effect

8.1 Spillover effect of flood on neighboring districts

Finally, we test for geographical treatment spillovers induced by the incidence of the floods. We modify equation (1) to include binary indicators of both flood-affected districts and their contiguous districts, as shown below:

where $neighbor_{d,t}$![]() is a binary indicator for neighboring districts of flood-affected ones. The rest of the variables are the same as in equation (1). If floods led to geographical spillovers, we would expect $\beta ^{neighbor}$

is a binary indicator for neighboring districts of flood-affected ones. The rest of the variables are the same as in equation (1). If floods led to geographical spillovers, we would expect $\beta ^{neighbor}$![]() to be negative and statistically significant.

to be negative and statistically significant.

Table 8 shows that the negative effects of floods on wages persist even with the inclusion of neighboring districts. These findings reveal no significant spillover effects of flood-induced shocks on wages of agricultural laborers in neighboring districts, strengthening our stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA) necessary for the validity of our empirical model.

Table 8. Impact of 2017 floods on cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers with the inclusion of neighboring districts

This table presents DID estimates from equation (4) that includes neighboring districts in the specification. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

8.2 Effect on wages across gender, caste, and religion categories

Nepal has heterogeneous population demographics that are geographically, socially, and economically different from each other. Hence, we perform our analysis on homogeneous sub-samples to assess the effects of floods on cash and in-kind wages. It helps us evaluate if the above estimates are consistent under a range of heterogeneous populations in Nepal. We focus on three primary categories related to gender, religion, and caste.

First, we evaluate the effects of severe flooding on the gender parity of agricultural laborers. Table 9 shows that the 2017 floods led to a strong, statistically significant effect on male laborers’ cash and in-kind wages. In contrast, table 10 shows that female laborers’ cash wages decreased significantly, but the estimates on in-kind wages are inconclusive.

Table 9. Difference in differences estimates for cash and in-kind wages for male laborers

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1) for a restricted sample of male agricultural laborers. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

Table 10. Difference in differences estimates for cash and in-kind wages for female laborers

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1) for a restricted sample of female agricultural laborers. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

As we find significantly different effects of flooding on the wages of male and female laborers, we further analyze if the 2017 floods exacerbated the gender wage gap in the region. Table 11 shows that the wage gap between male and female laborers increased significantly after the floods. Although natural disasters, in theory, affect both males and females equally, their impact on the labor market varies significantly for both genders and reinforces gender inequality in wages (Erman et al., Reference Erman, De Vries Robbe, Fabian Thies, Kabir and Maruo2021).

Table 11. Difference in differences estimates for cash and in-kind wages gap between male and female laborers

DID estimates from equation (1) for gap between male and female laborers. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

Second, we break down the overall effects of the 2017 floods on the wages of agricultural laborers across different religions. This is important because the 2021 Census of Nepal shows that 81 per cent of the country's population practices Hinduism while 8 per cent follows Buddhism (Dahal, Reference Dahal2003). Hindus are considered more affluent than their counterparts, with adequate resources and risk management strategies (Wagle, Reference Wagle2010). Table 12 shows that adverse effects of floods on cash wages exist for both Hindus and non-Hindus. However, the magnitude of the estimated impact is much more prominent among non-Hindu agricultural laborers. For example, although the floods caused about an 8 per cent decline in cash wages among Hindu laborers in the flood-affected districts, the corresponding effect is a 17 per cent decline among non-Hindu laborers. Strikingly, in-kind wages in the aftermath of the floods increased for Hindu and non-Hindu agricultural laborers significantly. However, the magnitude of the effect is marginally higher among Hindu laborers in flood-affected districts.

Table 12. Difference in differences estimates for cash and in-kind wages for laborers by religion

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1) for agricultural laborers by religion. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

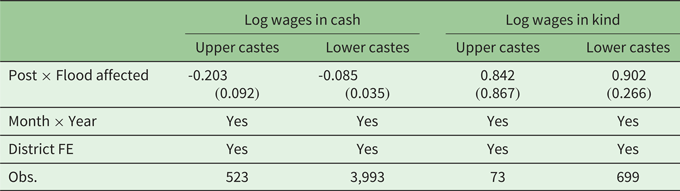

Finally, we explore the effects of floods on the wages of agricultural laborers among different caste categories. According to Nepal's 2011 census, 125 different caste groups reside in the country. We define binary indicators of the upper-caste (which includes Brahmins, Kshatriya (Chhetris), and Thakuris) and the lower-caste (which includes the rest of the caste groups) categories. Because laborers from lower-caste categories fulfill most agricultural field demand, a detailed exploration of whether flood-related shock affected their livelihoods is necessary. Table 13 reveals that cash wages of lower-caste laborers decreased as expected, but this effect appears to be more prominent among upper-caste laborers. It probably exists for two primary reasons. First, we believe this could be because of the base effect since the wages for upper-caste laborers are relatively higher than those for lower castes. Second, upper-caste laborers are not primary labor suppliers in the agricultural sector, implying that they can be easily substituted with lower-caste laborers, who are available in abundance. Regarding in-kind wages, the positive gains are driven mainly by agricultural laborers belonging to low-caste categories. However, we suffer from an inadequate sample size for upper-caste individuals.

Table 13. Difference in differences estimates for cash and in-kind wages for laborers by castes structure

This table presents DID estimates from equation (1) for agricultural laborers by caste categories. The upper castes category includes Brahmin (Hill), Brahmin (Terai), Kshatriya (Chhetri), and Thakuri castes only. Conley (Reference Conley1999) heteroskedastic and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors are reported in parentheses. The distance cutoff of 50 km is used for Conley standard errors.

9. Concluding remarks

This article explored the impact of disastrous floods on the cash and in-kind wages of agricultural laborers in Nepal. We tested the hypothesis that the floods would reduce the availability of money in the system, causing a reduction in wages in cash. Farmers mitigated these flood-induced economic losses through an increase in in-kind wages. Consistent with the hypothesis, we found empirical evidence that cash wages decreased by about 9–10 per cent in the aftermath of the floods. In contrast, income from in-kind wages increased by about 1.4–1.5 times. Event study estimates confirm that the effects of flood shock on wages and earnings persisted even after a year of flood events. Our analysis concludes that the most significant effect on reduced wages is driven mainly by districts severely affected by the floods. We also showed that female wages decreased significantly compared to male wages, implying that floods exacerbated gender disparities in cash wages. In addition, Hindus and non-Hindus saw reduced cash wages, but the effect was more substantial for non-Hindu groups. Finally, workers belonging to lower castes, who are primary suppliers of the workforce in the agricultural sector, appear to have been affected the most by the 2017 floods. Lower caste workers observed a reduction in cash wages and an increase in in-kind wages.

Our findings suggest that in-kind wages need to be considered, in addition to cash wages, to fully understand factors that determine household utility levels. This is especially relevant in the case of emerging economies heavily dependent on the agricultural sector. Our results have major policy imperatives. Policymakers could recognize in-kind wages as one of the critical risk-mitigating strategies in their post-shock recovery needs. Financial institutions could consider in-kind compensation a legitimate expense for the farmers and a critical factor in the agricultural loan application process. Based on household consumption patterns, disaster management institutions could procure buffer stocks of items that could be used as in-kind wages to partially mitigate the adverse effects of natural disasters.

The nature of our data, however, does not allow us to compute the combined income from cash and in-kind wages for laborers. We also do not have information on hours worked by individuals throughout the survey duration for calculating labor supply on intensive margins. As a result, we cannot accurately determine what share of the income from in-kind wages offsets the reduction in income from cash wages. Additionally, we note that in-kind wages are reported as a total sum, while cash wages are presented as a daily rate in NPR. To gain a deeper understanding of the enduring impact of the flood-induced shock on labor-related outcomes, comprehensive access to richer longitudinal data spanning an extended time frame would be ideal. Such data would enable us to better understand how labor dynamics evolve after the incidence of floods in the long run.

Further research is warranted on whether cash and in-kind wages can perfectly substitute each other during the incidence of environmental shocks. The degree to which wages reach a pre-shock equilibrium or we observe a status quo, in the long run, is an open empirical question. Researchers can also delve into which type of wages the laborers prefer and how such preferences influence their household consumption patterns.

Data

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.