1 Introduction

This article investigates the rise of do-support during the Scots anglicisation process, which accelerated from the late sixteenth century, catalysed by shifts in the sociopolitical relationship between Scotland and England. Anglicisation possibly involved a form of language shift initially, reflecting the behaviour of writers rather than a change in Scots itself, as evidenced by its varied impact on different genres at different times (Devitt Reference Devitt1989; Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993, Reference Meurman-Solin1997) and the more rapid shifts in more salient linguistic features (e.g. van Eyndhoven & Clark Reference van Eyndhoven and Clark2019). While anglicisation research often centres on lexis, orthography and phonology (e.g. Devitt Reference Devitt1989; Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993, Reference Meurman-Solin1997; Kniezsa Reference Kniezsa1997; van Eyndhoven & Clark Reference van Eyndhoven and Clark2019), the effects on syntax are less known. The newly constructed Parsed Corpus of Scottish Correspondence (PCSC; Gotthard Reference Gotthard2024b) begins to allow scholars to address this gap.

Do-support is the mandatory insertion of the auxiliary do, which historically underwent semantic bleaching and today has a strictly morphosyntactic function: carrying tense and agreement features. In Present-Day English (PDE) and Scots, do-support occurs in clauses with NICE properties: Negation (‘I don’t eat cake’ / ‘Don’t eat cake!’), Inversion (‘Do/Don’t you eat cake?’ / ‘What do you eat?’), Code (constructions which signify, or ‘code’, another verb phrase, e.g. ellipsis or tag questions: ‘I eat cake, and Alex does too’ / ‘You eat cake don’t you?’) and Emphasis (‘I do eat cake!’). English do-support is extensively researched, and, ever since Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953), many have detailed the quantitative and qualitative process of the grammaticalisation of do, and why it became mandatory in English alone of the Germanic languages (e.g. Denison Reference Denison1985; Kroch Reference Kroch1989; Nurmi Reference Nurmi1999, Reference Nurmi, Taavitsainen, Melchers and Pahta2000, Reference Nurmi, Kastovsky and Mettinger2011; Poussa Reference Poussa1990; Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade1990; Garrett Reference Garrett1998; van der Auwera & Genee Reference van der Auwera and Genee2002; Warner Reference Warner, Kay, Horobin and Smith2002, Reference Warner2005; Ecay Reference Ecay2015). The feature in Scots has received less attention, though it has been suggested that Scots do-support is a transfer from English, emerging during the height of anglicisation (Gotthard Reference Gotthard2019; Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993).

Drawing on Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) observations, Ecay (Reference Ecay2015) identifies an ‘intermediate do’ auxiliary in English before c. 1575, which exhibits a set of behaviours which are then lost in modern do-support: it occurs more frequently with agent-selecting verbs, less frequently with pronoun subjects, and more frequently in post-adverbial position. These behaviours decline in favour of a modern-type do-support simultaneously with the decline of affirmative declarative do in the late sixteenth century. Crucially, Scots do-support emerges after the intermediate do auxiliary declines in English.

This prompts the question of whether early Scots do follows a comparable trajectory, i.e. exhibits intermediate do behaviours, or emerges with the same function as post-1575 English do. If Scots do exhibits an intermediate-do function, it may be because it is an independent development in Scots rather than a transfer from English, based on the shared grammaticalisation criterion for contact-induced change; a feature showing the same grammaticalisation stages in the receiving language is likely to be an inherited feature rather than a transferred one (Pa-Tel Reference Pa-Tel2013; Robbeets & Cuyckens Reference Robbeets and Cuyckens2013). However, if Scots do is like intermediate do, this would not rule out the possibility that the intermediate do grammar could have diffused from Northern English into Scots, meaning that it is still a contact outcome while not an outcome of anglicisation.

Therefore, this study investigates whether Scots do-support is a plausible outcome of anglicisation by (i) assessing whether the contact situation with Southern English in the sixteenth to eighteenth century, when Scots do emerges, lends itself to structural transfer, and (ii) examining proportions of affirmative and negative declarative do in the PCSC across syntactic contexts relevant for an intermediate do analysis, to assess whether early Scots do had a similar function to intermediate do in English (per Ecay Reference Ecay2015).

Section 2 summarises the sociohistorical context when Scots do emerged, focusing on the nature of Anglo-Scots contact at different stages in history. Section 3 outlines theoretical assumptions about do-support (3.1), and scholarly theories regarding the rise of do-support in English (2.3) and Scots (2.5), with Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) intermediate do analysis detailed in section 2.4. Sections 3 and 4 outline the research question and methodology, respectively. The results are presented in section 5, and then, in section 6, assessed against criteria for contact-induced change (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988; Thomason Reference Thomason2001; Pa-Tel Reference Pa-Tel2013; Robbeets & Cuyckens Reference Robbeets and Cuyckens2013; Poplack & Levey Reference Poplack, Levey, Auer and Schmidt2010), to evaluate the likelihood of Scots do-support being an anglicisation outcome.

2 Background: Anglo-Scots contact

2.1 Social context and language contact

An important diagnostic for whether a change is contact-induced is social context: Thomason & Kaufman state that ‘[i]t is the sociolinguistic history of the speakers, and not the structure of their language, that is the primary determinant of the linguistic outcomes of language contact’ (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 35). This is supported by the fact that for linguistic constraints on contact-induced change, proposed in the literature, frequently, counterexamples in data from languages in contact can be found. Hence, it is crucial to understand the social context in which syntactic changes in Scots took place in order to assess whether they possibly could be contact-induced. A social predictor of contact-induced language change is intensity of contact, measured by the length of contact, numerical advantage of one group of speakers over the other, sociopolitical dominance of one group over the other and the level of bilingualism in the contact community (Thomason & Kaufman Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 67; Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 66).

Regarding length of contact, Scots and English, both stemming from Old English, have maintained close contact since their divergence in the eleventh century. However, as will be seen, the intensity of this contact has varied due to sociopolitical changes, and there are two significant points of contact with English which may have led to contact-induced change: (i) continuous close contact with Northern English dialects, from their earliest history and onwards, and (ii) contact with Southern English as a result of a shifting relationship between Scotland and England from the late sixteenth century, which can be described as a top-down contact scenario wherein English exerts influence on Scots (i.e. anglicisation). The social contexts of these contact scenarios, and their potential linguistic outcomes, will now be described in turn.

2.2 Contact with Northern English

Scots developed from Northumbrian Old English dialects after the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, with later influence from Northern Middle English and Anglo-Scandinavian from the eleventh century, meaning that Scots and North-East English dialects share close ancestry (e.g. Murison Reference Murison1979; Aitken Reference Aitken1979, Reference Aitken and Robinson1985; Macafee & Aitken Reference Macafee and Aitken2002; Millar Reference Millar2023). Until the mid sixteenth century, Scots developed independently, gradually becoming available for various communicative functions alongside, or instead of, Latin, French and Gaelic, in lowland Scotland (e.g. Havinga Reference Havinga2021; Kopaczyk Reference Kopaczyk2021). In this period, Scots maintained its distinct identity through a combination of unique Scots features and commonalities with Northern English dialects (Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1997). Anglo-Scots contact until the late sixteenth century can be described as a convergence scenario, where the two varieties coexisted without significant language shift. Despite the usual description of convergence contact, it does not require languages to be typologically different; for instance, the loss of past tense distinctions in French, Romantsch, Northern Italian dialects and Southern German, likely originated from convergence contact in border regions (Hock & Joseph Reference Hock and Joseph1996: 397).

This analysis is, however, not the traditional view of the relationship between English and Scots pre-anglicisation; the situation from the fifteenth century onwards is described as ‘differentiation’, i.e. divergence rather than convergence, by Meurman-Solin (Reference Meurman-Solin1997), implying that Scots in the fifteenth to sixteenth century is growing to be more distinct from English. However, there is no evidence that Scots is becoming more divergent in that time period – rather, at the time of our earliest attested running prose, in the late fourteenth century, Scots is already distinct from English in the ways described by Meurman-Solin (Reference Meurman-Solin1997).Footnote 1 Indeed, the features investigated in her work are already present at 100 per cent frequencies in texts from 1400, and decline in favour of their English counterparts at the start of anglicisation, around 1540. Hence, differentiation, or divergence, could perhaps be argued to have already happened before 1400, meaning that the situation in the fifteenth to sixteenth century is such that an already differentiated variety is in some form of convergence contact with Northern English.

Before the mid sixteenth century, English does not appear to have been sociopolitically dominant, or perceived as more prestigious than Scots, in Scotland (e.g. McClure Reference McClure and Burchfield1994: 34; Görlach Reference Görlach2002: 16; Millar Reference Millar2020: 79–80). In fact, despite high levels of orthographic and lexical variation, there is plenty of indication that Scots was on a separate standardisation trajectory from English in the fifteenth to sixteenth century (Agutter Reference Agutter1990; Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1997; King Reference King1997: 157; Bugaj Reference Bugaj2004). Towards the end of this period, Scots writers show signs of ‘involuntary language shift’ (in the sense of Joseph Reference Joseph1987), as the linguistic similarity between the languages, and their similar status, meant that English was easily incorporated in Scots writing. The long duration of contact between Scots and English, the fact that there was no established Scots written norm, and that they did not appear to compete politically, facilitates precisely this type of language mixing; Muysken (Reference Muysken2012: 713–14) describes a type of code-switching, congruent lexicalisation, as a typical outcome of such contact scenarios between structurally similar languages, involving inserting words from either language into a shared structure (e.g. Catalan/Spanish ‘Això a él a ell no li i(m)porta’, from Muysken (Reference Muysken2012: 713)); this aptly describes the Scots–English form alternation in Scottish texts from before the mid sixteenth century.

As Scots and English likely maintained mutual intelligibility, assessing the level of bilingualism, and, consequently, the numerical advantage of one group over the other in Scotland, is challenging – the situation between Scots and Northern English speakers in Scotland in the fourteenth to sixteenth century may be compared to that of Old English (OE) and Old Norse (ON) speakers in the Danelaw; at the time of the Viking settlement of England, OE and ON had only diverged for about 300 years, and, as demonstrated by Townend (Reference Townend2002), the Danelaw communities, but not individuals, were likely bilingual, as the languages were similar enough that mutual intelligibility is probable. Ultimately, however, ON speakers shifted to English, which is argued to have caused significant structural change in English (e.g. the loss of verb-second (Kroch et al. Reference Kroch, Taylor, Ringe, Herring, van Reenen and Schøsler2000)). Even in contact between mutually intelligible varieties, there tends to be speaker accommodation, leading to levelling and simplification (cf. Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986; although see Mufwene (Reference Mufwene2008: 255–6) on why levelling cannot be the only outcome, as is evident from rich dialectal variation). Thus, regardless of individual bilingualism, contact between very similar languages could lead to structural change – in fact, less intense contact is needed for structural transfer to take place between typologically similar languages than between those that are more typologically divergent (Thomason Reference Thomason2001: 71).

Due to the shared ancestry of Northern English and Scots, teasing apart what are internal developments and what is transfer in this contact situation is notoriously challenging – even more so because the syntactic variation of both varieties is not yet fully documented. However, investigating whether structural transfer took place between Southern English and Scots may prove less speculative, due to their higher level of linguistic distinctiveness; as will be seen in the next section, sociopolitical shifts in the sixteenth to eighteenth century are likely to have been conducive to such transfer.

2.3 Shifting relationships: contact with Southern English

From the late sixteenth and throughout the seventeenth century, there was a critical shift in the trajectory of Scots and its relationship with English. Scots saw its use limited in influential institutions in Scotland as Southern English emerged as the language associated with religion, the monarchy, legislation, administration and the majority of printed works, catalysed by events like the Reformation in 1560, the proliferation of print from the late sixteenth century, the Union of Crowns in 1603 and the Union of Parliaments in 1707 (Murison Reference Murison1979; Aitken Reference Aitken and Robinson1985; McClure Reference McClure and Burchfield1994; Macafee & Aitken Reference Macafee and Aitken2002; Millar Reference Millar2020, Reference Millar2023). Consequently, English became the language of high registers and written Scots had limited use after the eighteenth century, mainly employed in literary genres, or writings intended for local audiences, such as local popular press media in the eighteenth to twentieth century (Görlach Reference Görlach2002: 183–5; Filgueira et al. Reference Filgueira, Grover, Karaiskos, Alex, van Eyndhoven, Gotthard and Terras2021; van Eyndhoven et al. Reference van Eyndhoven, Gotthard, Filgueira, Laitiainen, Taipale and Rautionahoforthcoming). However, Scots features persisted in private correspondence in the eighteenth century (e.g. Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993; Gotthard Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a; van Eyndhoven Reference van Eyndhoven2021; Cruickshank Reference Cruickshank2012). This dramatic shift, wherein writers increasingly use English features instead of Scots ones, is traditionally called the anglicisation of Scots.

The present-day outcome of anglicisation in spoken Scots, as characterised by Stuart-Smith (Reference Stuart-Smith, Kortmann and Schneider2004), following Aitken (Reference Aitken1979, Reference Aitken and Trudgill1984), is a bipolar continuum, with traditional Scots dialects on one end and English varieties, including Scottish Standard English (SSE; see, e.g., Maguire Reference Maguire and Hickey2012; Millar Reference Millar2020: 107–9) on the other, where speakers typically mix features of both varieties, using more features from either end of the continuum depending on context. Scots has never been a homogeneous variety, and never had a codified standard to converge on, which has allowed regional and social variation to thrive in Scots speech, but has also rendered Scots vulnerable to dialect levelling toward English or SSE supralocal norms. The intra- and interspeaker variability resulting from this simultaneous divergence and convergence contributes to the difficulty in defining Present-Day Scots as a language distinct from English. Hence, the period between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries seems a ‘transition’ period for Scots (Kopaczyk Reference Kopaczyk, Millar and Cruickshank2013: 253), as it goes from being a standardising variety, to the diverse, socially and regionally conditioned, linguistic landscape we encounter in Scotland today.

Thus, the late sixteenth century marked a shift in Anglo-Scots contact, transitioning from convergence with, mainly Northern, English, to a substrate–superstrate relationship with Southern Standard(ising) English. Features borrowed before this shift suggest a lower ranking on Thomason & Kaufman’s (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 74–6) borrowing scale, possibly at level 2 (see table 1). Indeed, orthographic, phonological and morphological features described by, for example, Kniezsa (Reference Kniezsa1997) and King (Reference King1997), and investigated by Meurman-Solin (Reference Meurman-Solin1993, Reference Meurman-Solin1997), Devitt (Reference Devitt1989) and van Eyndhoven & Clark (Reference van Eyndhoven and Clark2019), all appear to resist Southern English influence before the mid sixteenth century; due to the overlap between Northern English and Scots features, resulting from their shared ancestry, it is more difficult to say whether borrowing is feasible here.

Table 1. The borrowing scale, adapted and abbreviated from Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 74–6)

Less is known about Scots syntactic change, but previous research indicates that fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Scots is unaffected by major syntactic changes happening concurrently in Southern English. These changes, which would fit at level 4 on the borrowing scale, instead take place in Scots during the anglicisation period; until the late sixteenth century, Scots does not develop a Standard English subject–verb agreement paradigm (Gotthard Reference Gotthard2022, Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a), the verbalisation of gerunds does not take place (Zehentner Reference Zehentner2014; Gotthard Reference Gotthard2022), verb-raising is retained and do-support is absent (Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993; Gotthard Reference Gotthard2019, 2024a; and the findings of the current article). While the timing of these changes alone does not confirm that they are anglicisation outcomes (see section 7), we can at least deduce that structural transfer from Southern English before anglicisation is not evident.

Hence, as high-intensity contact with Southern English, per Thomason & Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988), began with the increased sociopolitical dominance of English, particularly after the Union of Crowns in 1603, the social context in the sixteenth to eighteenth century appears conducive to contact-induced structural change, which means that a transfer of do-support from Southern English to Scots is possible.

3 Background: do-support

3.1 Do-support: theoretical assumptions

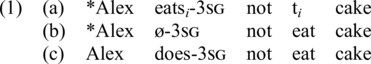

Do-support involves inserting the auxiliary do in a clause to express tense and agreement features when the transfer of these features between the subject and main verb is disrupted, and no other auxiliary is present. In the generative framework, do merges in a position analysed as the head of a functional projection below C but higher than VP in the syntactic structure (e.g. T(ense) or AGR(eement), typically called I(nflection) before Pollock’s (Reference Pollock1989) Split IP-Hypothesis), and is often considered a last-resort operation to establish subject–verb agreement, necessitated by the loss of verb-raising (main verb movement from VP to a higher position). Verb-raising is understood as motivated by the need to express the feature-content of a syntactic head (e.g. T) to agree with the subject in the specifier position (e.g. spec,TP). Following the loss of verb-raising, this operation became restricted to auxiliaries, which are in complementary distribution with do. Footnote 2 Consequently, lexical verbs could only achieve subject–verb agreement if there was no intervening material between T and V, necessitating the insertion of do in those clauses; (1a) illustrates what verb-raising would surface as in modern English (now ungrammatical), (1b) the failed agreement caused by the loss of verb-raising, where the negator is the intervening element, and (1c) the grammatical clause with do insertion.

In PDE, and supposedly in Scots, the auxiliary itself has no meaning, and no other function than to spell out features in the manner described – for this reason, do is often referred to as a ‘dummy’ auxiliary.

3.2 Do-support in English: its origin and development

The origins of do lie in Old English (OE), the ancestor of both English and Scots. OE do had other functions, as illustrated in (2); causative do (2a), anticipative do (2b), substitute do (2c). Anticipative and substitute do remain in PDE (code, under the NICE properties).

Causative do (2a) persists in other modern West-Germanic varieties, e.g. Dutch (van der Horst Reference van der Horst, van Leuvensteijn, van Ostade and van der Wal1998: 57), but is lost in PDE – this early function of do has commonly been identified as a probable source for the grammaticalisation of do, initially by Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953). While the presence of more semantically vacuous do auxiliaries with code properties may also have influenced the development of a dummy do auxiliary (see, e.g., Moretti Reference Moretti2024), the causative construction has the advantage of combining a do auxiliary with an infinitival verb, which is the same syntactic pattern of PDE clauses with do (except for in code contexts; e.g. Fischer & van der Wurff Reference Fischer, van der Wurff, Hogg and Denison2006: 154–5; Garrett Reference Garrett1998: 287–91). In Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) early proposal for the grammaticalisation of causative do, he posits that the meaning of do was susceptible to reanalysis in clauses with ambiguous agents. Eventually, do auxiliaries with unambiguously non-causative meaning emerged, with the earliest examples from the western Midlands in the Middle English (ME) period.

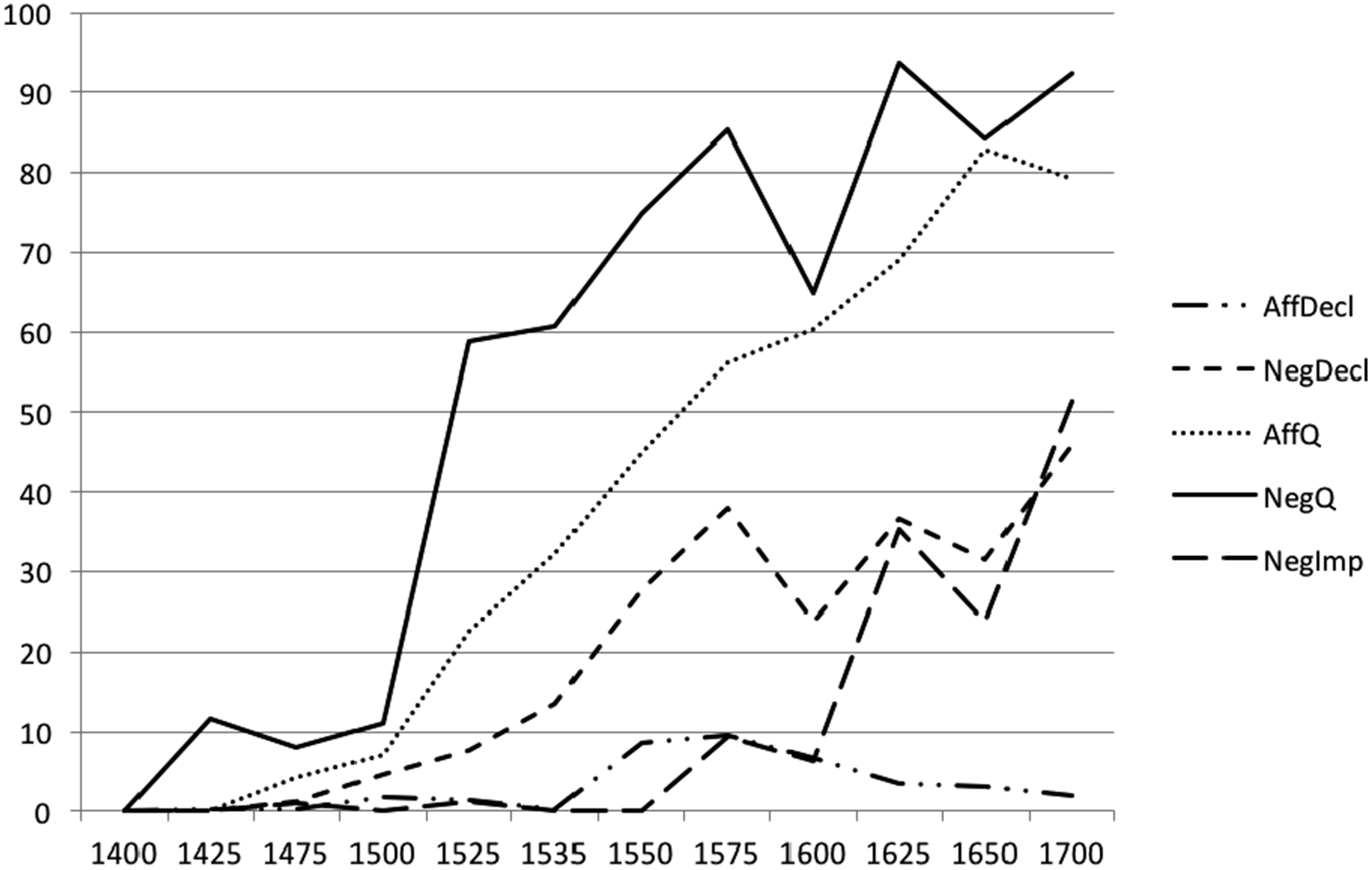

Extensive data collection on English do-support has facilitated a quantitative mapping of its spread in different clause types, from the emergence of non-causative do constructions, as illustrated in figure 1 (adapted from Los Reference Los2015). Notably, it was for a period possible to apply do-support in affirmative declarative clauses – this is a non-emphatic, semantically vacuous do, and not the emphatic function of PDE do – which declined while do-support increased in other contexts.

Figure 1. The spread of do-support in Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) corpus

AffDecl=Affirmative Declarative; NegDecl = Negative declarative; AffQ = Affirmative Question; NegQ = Negative Question; NegImp = Negative Imperative

Kroch (Reference Kroch1989: 219) finds that do-support was introduced into all appropriate contexts in English at the same time, but at different frequencies, i.e. a simultaneous unequal actuation, but that the rate of change is consistent across all contexts, thus providing key evidence for Kroch’s (Reference Kroch1989) Constant Rate Hypothesis. Differences in frequencies at a given time may be affected by stylistic or functional factors; indeed, during its regulation, before being integrated into English grammar as a syntactic rule, do was conditioned by extra-syntactic factors, such as narrative styles and social constraints (see, e.g., Nurmi Reference Nurmi1999, Reference Nurmi, Taavitsainen, Melchers and Pahta2000, Reference Nurmi, Kastovsky and Mettinger2011; Stein Reference Stein1985: 292–6; Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade1990: 26–7; Warner Reference Warner, Kay, Horobin and Smith2002, Reference Warner2005).

The emergence of do-support in the West Midlands has prompted theories of Celtic substratum effects, through contact with a Brythonic ancestor of Welsh in the OE period, notably argued by Poussa (Reference Poussa1990), supported by the presence of periphrastic do constructions in Celtic languages. Scepticism towards such theories arises due to their reliance on an assumed unattested form of do-support used in the West Midlands before the ME period (e.g. Garrett Reference Garrett1998: 286). An alternative perspective suggests that the do constructions in early Celtic and English dialects are an areal feature (Hickey Reference Hickey, Nevalainen and Traugott2012: 501–3), as do constructions exist in other Germanic languages despite little Celtic contact. The strength of Poussa’s (Reference Poussa1990) account lies in her theory that language contact prompts more frequent use of dummy auxiliaries. Do may have been used as a facilitator verb, letting speakers avoid the challenge of fitting new verbs into their inflectional system by instead pronouncing features on do; Fischer & van der Wurff (Reference Fischer, van der Wurff, Hogg and Denison2006: 155) note that do initially occurred more frequently with verbs borrowed from French (cf. Shaw & De Smet Reference Shaw and De Smet2022). Indeed, do-support is more frequent in data from English pidgins, creoles, L2 varieties, code-mixing and children’s speech, than in standard varieties (see also Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade1990: 19–24; van der Auwera & Genee Reference van der Auwera and Genee2002: 287; Hickey Reference Hickey, Nevalainen and Traugott2012: 502; this facilitator verb function is often the function of do periphrasis in other Germanic languages).

Thus, the origins of the dummy auxiliary do may be neither solely language-internal nor external: the presence of a do auxiliary in OE and its occurrence in other Germanic languages suggest a common Germanic origin (cf. Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade1990; Langer Reference Langer2001). This auxiliary expanded its use and underwent semantic bleaching in varieties spoken only in Britain, a process which apparently began in areas where there was contact with Celtic languages which had verbal periphrasis with do, i.e. the West and South-West of England.Footnote 3 Without tracing the origin of auxiliary do structures to direct transfers or calques into English, it remains plausible that this unique contact situation could accelerate or catalyse a distinct development of do compared to other Germanic languages,Footnote 4 even if the origin of the auxiliary is language-internal.

3.3 Intermediate do

The syntactic function of English do varied before settling into its present-day usage, and much scholarship, e.g. seminal work by Denison (Reference Denison1985) and Garrett (Reference Garrett1998), aims to capture what may have conditioned do after the causative use declined and before it became a dummy auxiliary (see also recent work by Moretti (Reference Moretti2024)). Ecay (Reference Ecay2015) explores this further through comprehensive quantitative study of factors affecting the rise of do, replicating results by Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953) and Warner (Reference Warner2005), using data from the Penn Parsed Corpora of Historical English (PPCHE; Kroch Reference Kroch2020) and the Early English Books Online (EEBO) corpus. Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) findings shed light on a reanalysis of do before and after the frequency ‘dip’ around 1575 in Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) data (see figure 1) – this is roughly when Nurmi (Reference Nurmi, Kastovsky and Mettinger2011) observes a rapid adoption of do by female writers, but in her data, from the Corpus of Early English Correspondence (CEEC; Nevalainen et al. Reference Nevalainen, Raumolin-Brunberg, Keränen, Nevala, Nurmi and Palander-Collin1998), this dip is slightly later, around 1600. Warner (Reference Warner2005) suggests that the dip marks a stylistic reanalysis of the don’t contraction, finding more negative do in higher-complexity texts pre-1575, and the opposite correlation post-1575. In replicating Warner’s results, Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 66–73) identifies a complexity effect on affirmative do as well, which suggests that it is do-support itself that undergoes a re-evaluation. This re-evaluation, or reanalysis, is thus reflected by a dip in do frequencies before it rapidly increases again and eventually becomes mandatory.

Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) analysis reveals an ‘intermediate do’ auxiliary pre-1575, displaying distinct syntactic behaviours from the version of do that sees increased usage after 1575. Specifically, he proposes that intermediate do functions as an agentive marker, merging in a lower syntactic position than post-1575 do. This analysis follows observations by Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953) that do-support is initially more frequent in post-adverbial positions and with pronoun subjects, and is resisted by a specific class of verbs (know, doubt, care, fear, boot, list, mistake, skill, trow; henceforth, Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) know class). The timing of this intermediate do is particularly relevant for this study, as do-support emerges in Scots (at relevant frequencies) after the proposed intermediate-do stage, i.e. after 1575 (see section 3.4). Therefore, a closer look at Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) findings is warranted.

3.3.1 Position relative to adverbs

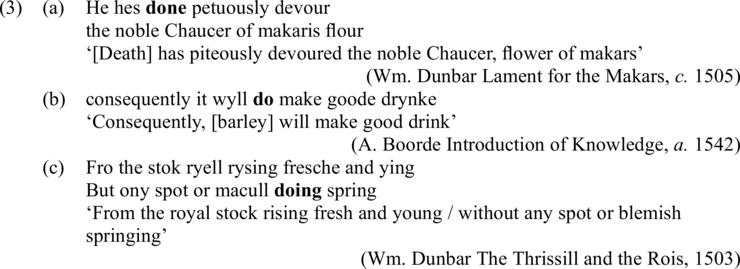

Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) observation that do is initially more frequent in post-adverbial positions gives rise to the hypothesis that do initially held a low position in the clause (i.e. lower than the present-day I/T position, but higher than VP). Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 76) highlights the examples in (3) as further evidence for this hypothesis.

The analysis does not address the origin of examples (3a) and (3c), from Scottish writer William Dunbar; Görlach (Reference Görlach2002: 108) mentions (3a) as a type of do used in Older Scots but not in English. Gotthard (Reference Gotthard2019: 6) does not see these constructions as a form of do-support, due to do being non-finite and primarily functioning to mark tense in verse (Macafee & Aitken Reference Macafee and Aitken2002: 7.8.15). Both examples from Dunbar appear to fall into this category – the example from (the Englishman) Boorde (3b) may offer more reliable evidence of a low do analysis. However, rather than looking further at co-occurrence with other auxiliaries or modals, Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 77–8) tested the hypothesis of intermediate do’s lower position by comparing its placement relative to clause-medial adverbs, contrasted with the position of modal auxiliaries and the auxiliary have. He observed that, while other auxiliaries occurred pre-adverbially from the early fifteenth century, do initially appeared post-adverbially (e.g. he often did see it) until it became more established in the early sixteenth century, then increasingly shifting into pre-adverbial position (e.g. he did often see it) and aligned with other auxiliaries by the late seventeenth century.

3.3.2 Argument selection

Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) observation that know-class verbs resist do-support led Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 78–82) to investigate the behaviour of do across different verb classes: he extracts 12 high-frequency verbs (including orthographic variants) from the PPCHE, categorised into two broad semantic classes, unaccusative and experiencer-subject, with 6 verbs each. Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) unaccusative class, including verbs that do not select an agentive external argument, includes arise, come, die, go, rise, stand, and his experiencer-subject class, corresponding to Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) know class, contains care, doubt, dread, fear, know, like. He categorises the remaining verbs as unergative (verbs without a direct object) and transitive (verbs with a direct object). Ecay’s experiencer-subject class is so called due to the generalisation that Ellegård’s know-class verbs take experiencer subjects, but he acknowledges that this might not be the most fitting generalisation (Ecay Reference Ecay2015: 78). Indeed, these types of verbs are typically used as hedging devices and in parenthetical commentary clauses (cf. Bolinger Reference Bolinger1977: 127; Chan & Tan Reference Chan and Tan2009: 102), making them more likely to appear with first-person subjects in their active form.

Ecay’s findings support a do reanalysis around 1575: before 1575, there is a clear preference for negative declarative do with the unergative and transitive verbs, i.e. verbs selecting agentive subjects, while the unaccusative and experiencer-subject classes ‘catch up’ in the early seventeenth century. Affirmative declaratives present a slightly different scenario, with the unaccusative class of verbs as the sole outlier, occurring less frequently with do-support than other verb classes (including experiencer-subject). This leads to the interim conclusion that intermediate do functioned as an agentivity marker. However, when applying this analysis to the EEBO data, the semantic classification effect is less clear, revealing lexically specific effects, particularly with verbs like regard and know. Consequently, Ecay tentatively suggests that ‘certain unaccusatives, as a group, are delayed in their progress along this trajectory [and] other specific lexical items may also show oddities’ (Reference Ecay2015: 125).

3.3.3 Subject type

The final observation from Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953) investigated by Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 86–8) is the preference for do-support with non-pronominal subjects. Throughout the period of affirmative declarative do-support usage, a robust subject-type effect is identified; do-support appears with pronominal subjects at significantly lower frequencies than with other subjects, and negative declaratives and affirmative interrogatives lose this effect after the dip in 1575.Footnote 5 Differences between pronominal and nominal subjects in historical data are not unexpected, given their different information-structural status and historical structural positions in the clause (e.g. Haeberli Reference Haeberli2002; Biberauer & van Kemenade Reference Biberauer and van Kemenade2011). The crucial finding is that there is a similar behaviour of affirmative declarative do and pre-1575 do in imperative, interrogative and negative declarative clauses, and that this apparent constraint on do-support is lost post-1575, when affirmative declarative do also declines. In Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) analysis, this suggests two underlying do-support grammars in Early Modern English, with one surpassing the other around the 1575–1620 reanalysis when lexical verbs stopped raising above adverbs completely. While Ecay (Reference Ecay2015) terms this an ‘intermediate’ do grammar, it could represent a distinct grammar; then, the intermediate do grammar would not be a stage in the grammticalisation of do, but rather be a failed system which became reanalysed into the dummy do grammar. This analysis may give rise to the implication that the ‘failed change’, which affirmative declarative do has often been deemed to be, is in fact the failed change of the whole intermediate do system. Accounting for the mechanics of these grammars goes beyond the scope of this study, but the syntactic behaviour of English do-support pre- and post-1575 is pertinent to the investigation into whether do-support was transferred from English to Scots in the late sixteenth century.

3.4 The development of Scots do-support

Scots do-support is far less researched than English do, with only three quantitative studies to date: Meurman-Solin (Reference Meurman-Solin1993), Gotthard (Reference Gotthard2019, 2024a). Jonas (Reference Jonas and Lighfoot2002) provides a more qualitative account of verb-raising in Older Scots, focusing on Shetland. Otherwise, Older Scots do-support is accounted for briefly in more descriptive works (such as Aitken Reference Aitken1979; Beal Reference Beal and Jones1997; Görlach Reference Görlach2002), or not at all, either because the focus of description is on pre-anglicisation Scots features, or because it is assumed to operate identically to English.

Previous studies on the rise of Scots do have not definitively identified the origin of Scots do-support. The descriptive literature offers speculative options: Scots might have independently developed do-support, as Scots, like English, inherited the OE causative do auxiliary, and utilised a special do in verse (as seen in (3), in section 3.3.1). Early usage of Scots do as a tense marker in verse or as a narrative device also shows parallels with early English do: Meurman-Solin’s (Reference Meurman-Solin1993) study on do-support in the Helsinki Corpus of Older Scots (HCOS; Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1995) finds higher frequencies of do-support in the past tense – which is expected if do has a narrative function (cf. Brinton Reference Brinton1996) – and in trial transcriptions, pamphlets and diaries, where this kind of narrative function is expected.

However, a language-internal theory insufficiently explains why Scots do-support emerges almost 200 years later than in English, beginning in the mid sixteenth century (Meurman-Solin Reference Meurman-Solin1993; Gotthard Reference Gotthard2019). Gotthard’s (Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a) study, using PCSC data, is the first to measure do proportions in Scots comparably to English do-support studies: measuring proportions only within present tense clauses, affirmative declarative do remained consistently below 1.3 per cent, and negative declarative do maintained stable but low frequencies throughout the seventeenth century, peaking at 12 per cent, before rising to an average of 34 per cent in the 1720–47 period.

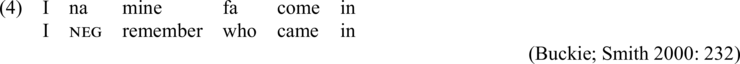

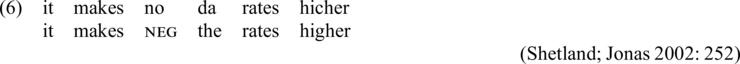

In the present day, do-support is variable in some dialects, as seen in negative declaratives in Buckie (4; North-East) and Shetland (6), and questions (5) in Shetland.

Jamieson (Reference Jamieson2015) and Jonas (Reference Jonas and Lighfoot2002) attribute these outcomes to language contact, both early contact between Norn and Scots, and contact with anglicised Scots from the sixteenth century; Jonas (Reference Jonas and Lighfoot2002: 270) suggests that the loss of verb-raising in Scots is an anglicisation outcome. Hence, variable do-support in Shetland may have resulted from the unique contact situations there.

The structure in (4) might represent a different phenomenon, which, according to the Scots Syntax Atlas (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Adger, Aitken, Caroline Heycock and Thoms2019) is widely accepted by both young and old speakers in the North-East of Scotland.Footnote 6 In Buckie, variable do-support only occurs with subjects that historically had ø-inflection on the verb under the Northern Subject Rule (NSR; plural and first-person singular (1sg) pronouns), and is obligatory, as in Standard English, elsewhere (Smith Reference Smith2000). Gotthard’s (Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a) investigation into whether NSR subject types influenced do-support’s development found no convincing effect, suggesting that other conditioning factors drove the historical variation.

The North-East and Shetland dialects are often considered representative of ‘broad Scots’, implying less anglicisation compared to, for example, central Scottish dialects. Variable do-support in these varieties is, thus, potential evidence of residual Older Scots grammar – i.e. do-support may be an anglicisation feature rather than a language-internal development. However, Scots exhibits rich regional variation, and this variability could also result from internal developments in these dialects.

Thus, earlier studies pinpoint the emergence of Scots do-support in the mid to late sixteenth century, measure do at low frequencies throughout the seventeenth century and report variability in some present-day dialects. Nonetheless, the exact nature of this development remains unclear, and past research has not determined whether Scots do-support is an outcome of anglicisation.

4 Research question and predictions

In order to gain more clarity of the origin and development of Scots do-support, the following research question (RQ) will be investigated:

RQ: Does Scots do-support exhibit similar features to English ‘intermediate do’?

If early Scots do lacks intermediate do features, it would align with an analysis of do-support as a transferred structure from Southern English, with post-1575 English do qualities. However, if early Scots do-support shares similarities with intermediate do, the origin of Scots do becomes more obscure: this scenario could be interpreted as (i) indicative of an ‘intermediate do grammar’ diffusing northwards from English to Scots – i.e. a result of contact with Northern English – or (ii) evidence of English and Scots do-support undergoing parallel developments, following a similar grammaticalisation pattern.

5 Method

5.1 Corpus, data retrieval and analysis

The data source for this study is the Parsed Corpus of Scottish Correspondence (PCSC; Gotthard Reference Gotthard2024b; described in Gotthard (Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a) and more extensively in Gotthard (Reference Gotthard2022: 27–46)). The corpus consists of 270,553 words of correspondence data, which is assumed to reflect a more oral style than other genres (e.g. van der Wal & Rutten Reference van der Wal and Rutten2013; Dossena Reference Dossena and Anderson2013), and has been found to resist anglicisation for longer; Meurman-Solin (Reference Meurman-Solin1997: 8) reports a sustained use of distinctively Scots variants in ego-documents (e.g. correspondence and journals) and legal writings, even after a significant decline in the use of such features in other genres after 1650. The PCSC, parsed in the PPCHE format (Kroch Reference Kroch2020), can be queried automatically using the CorpusSearch2 (CS) tool (Randall 2000/Reference Randall2013), tailored for PPCHE-style corpora.

To investigate whether the do type emerging in late sixteenth-century Scots exhibits behaviour similar to Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) intermediate do, or aligns more with post-1575 English do, a CS coding query was written to identify clauses coded for subject type (pronominal, non-pronominal or nullFootnote 7), finite verb type (be, have, do or a lexical verb), polarity (affirmative or negative) and adverb position – whether adverbs occurred between the subject and finite verb or after the finite verb.Footnote 8 A comparable method to Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 78–9) was used in retrieving representative samples of lexical classes of verbs, using the following steps:

-

1. All finite verbs, and all infinitival verbs that are sisters to finite do (i.e. main verbs in do-support clauses), were extracted with CS queries and sorted into a list with the frequency of occurrences given for each verb (a feature of the CS make_lexicon function).

-

2. High-frequency verbs from the list were manually sorted into 3 semantic classes, with 7 representative high-frequency verbs per class: agentive, unaccusative and k-class (from know class, in line with Ellegård’s original label). Thus, the main difference from Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) classification is that the unergative and transitive classes were collapsed into one agentive class. This initial selection essentially determined 7 semantic lemmasFootnote 9 per class.

-

3. The 7 lemmas were added as variables in a CS .def file and the verb lists were manually checked to add all variants belonging to a lemma to the relevant variable.

-

4. Two more columns were added to the coding query to find the particular lemmas and to categorise them according to their semantic class. This made it possible to correlate lemmas and semantic classes of verbs with the other clause features.

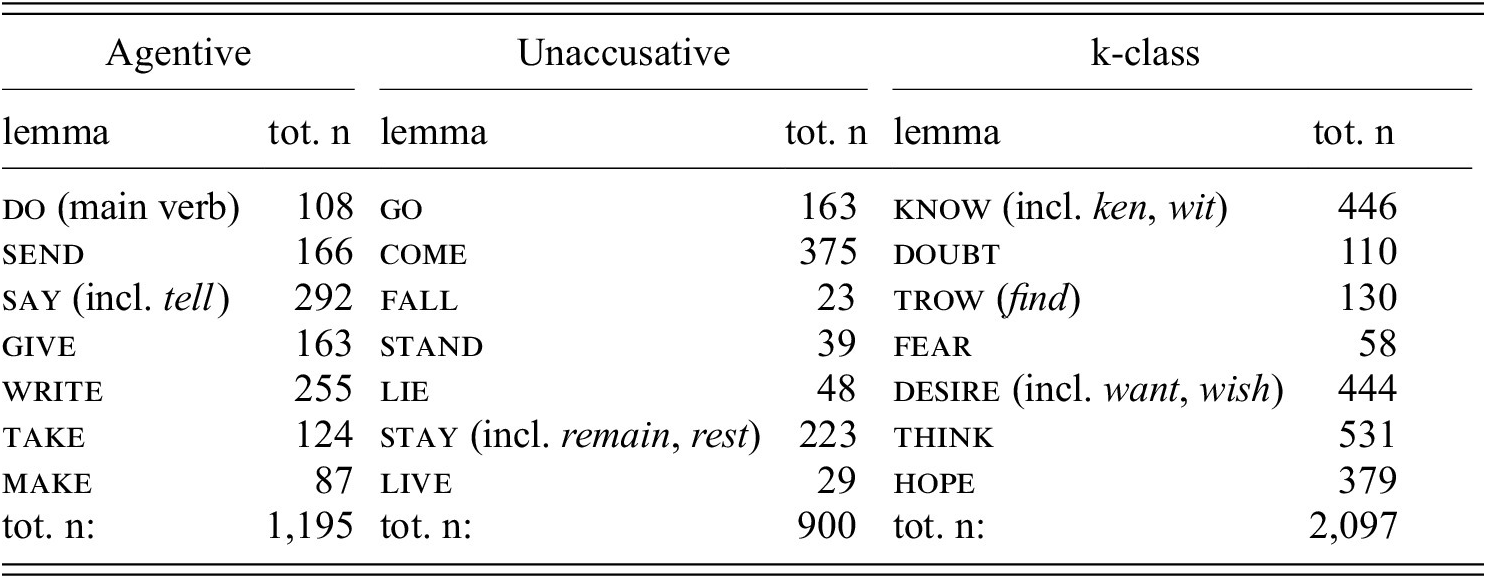

Table 2 presents the semantic lemmas, with the lexical items they denote and their absolute frequencies (including both finite verbs and infinitive verbs in do-supported clauses).

Table 2. Semantic classes and their representative lemmas, with absolute frequencies

The CS query output was then imported into R (R Core Team Reference Team2021) for statistical analysis. With the presence of the finite auxiliary do as the dependent variable, frequencies of do-support were calculated separately for affirmative and negative declarative clauses, as well as for each of the features relevant for intermediate do (i.e. by verb class, clause position relative to clause-medial adverbs, and subject type). For the argument-selection investigation in section 6.2.1, only clauses which had semantically lemmatised verbs were counted. In Gotthard (Reference Gotthard, Caon, Gordon and Porck2024a), proportions of do were calculated by taking frequencies per twenty-year time intervals, which provides a sense of the overall proportions of present tense do in the PCSC without any parametric assumptions. In this study, to reduce some of the noise, the data has been fitted to a loess curve, with year as a continuous rather than binned variable. The loess method fits a smooth but flexible curve to the data, and helps to visualise general trends, although it adds a level of abstraction from the raw data.

5.2 Note on interrogatives and imperatives

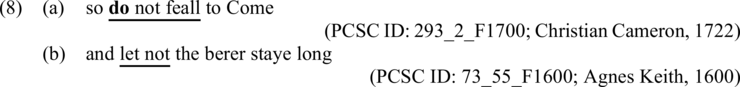

Though interrogative and imperative do were initially part of the study, the analysis yielded inconclusive results due to the low number of such clauses. Among 25 matrix questions (21 affirmative, 4 negative), only 3 met the criteria for do-support (i.e. Wh-object or polar question with no other auxiliary present). Of these, 2 instances had do-support, as illustrated in (7), with the relevant part of the clause underlined and do in bold font.

Negative imperative do occurs first in 1660, occurring 9 times out of a total 49 negative imperative clauses which did not use another auxiliary or a modal. The difference between pre-1660 and post-1660 is coarse-grained but significant with respect to imperative do (p < 0.001, according to a two-strand t-test). Examples in (8) show negative imperatives with (8a) and without (8b) do.

The rarity of such constructions in the corpus may stem from the formality of these letters. Recent research on eighteenth-century correspondence data indicates that writers employ various discourse strategies for requests, instead of using matrix questions (Elsweiler Reference Elsweiler2022, Reference Elsweiler2023). It is reasonable to infer that, for politeness, imperatives, expressing commands, are likewise avoided.

6 Results

6.1 The rise of do in the PCSC

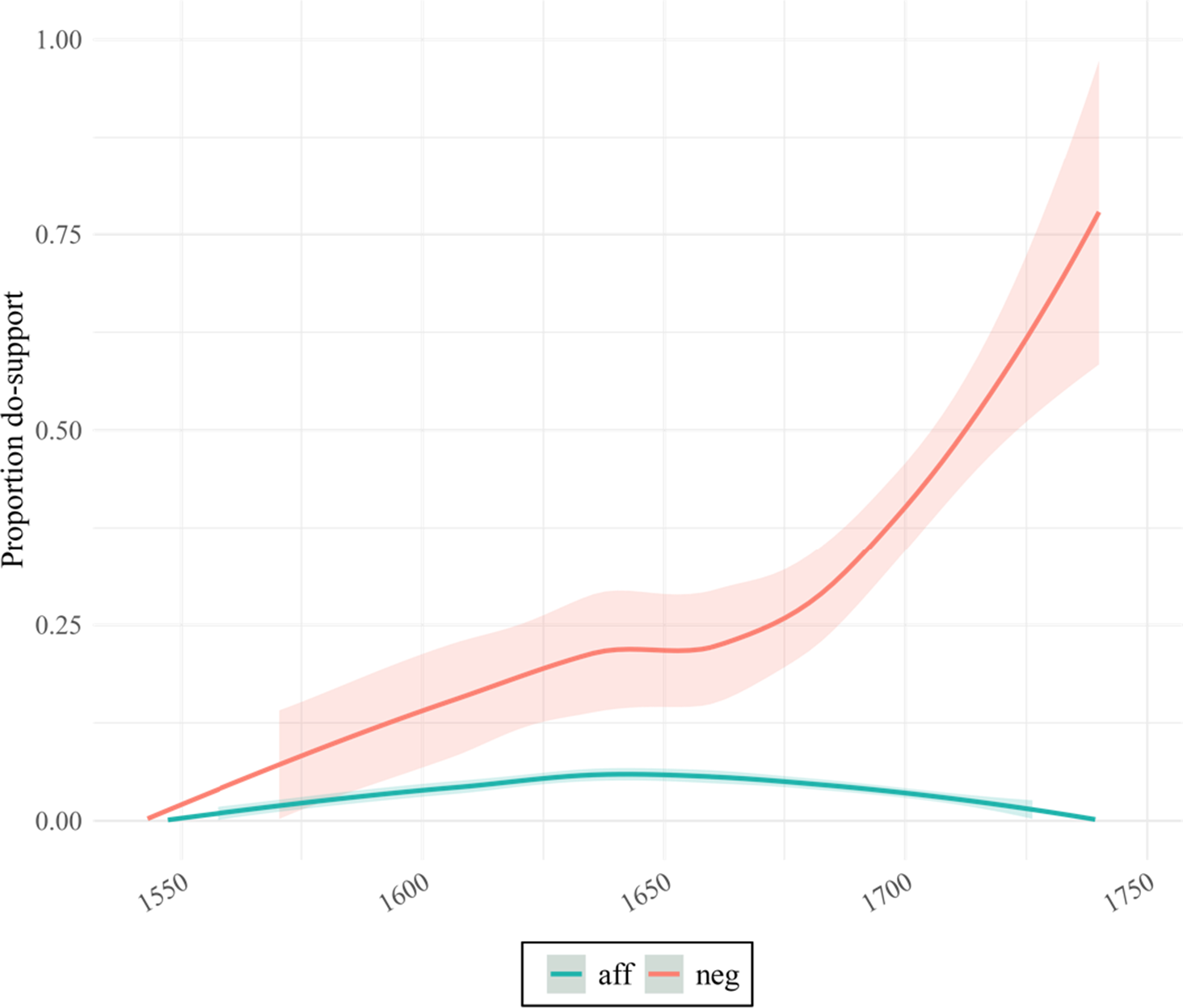

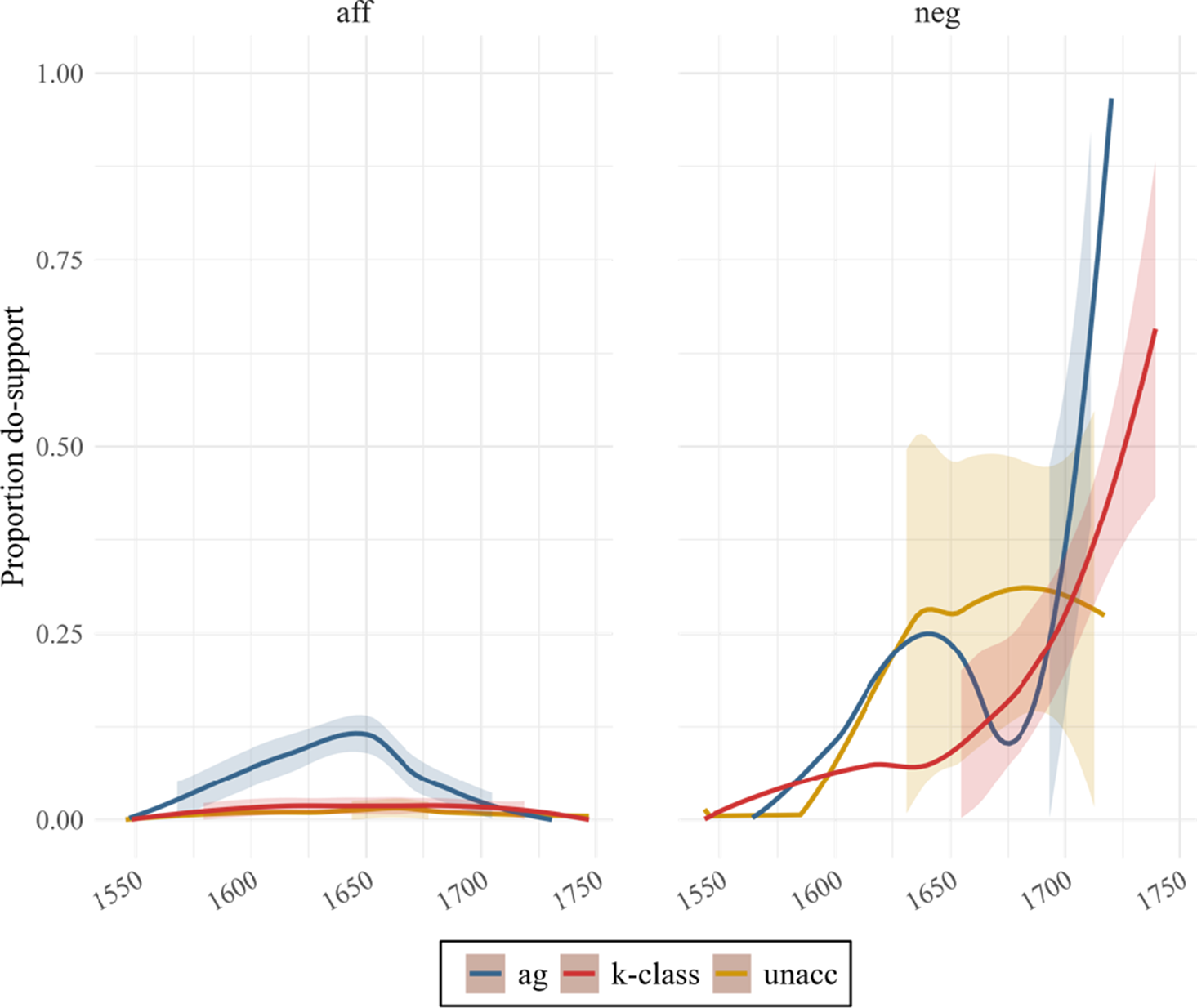

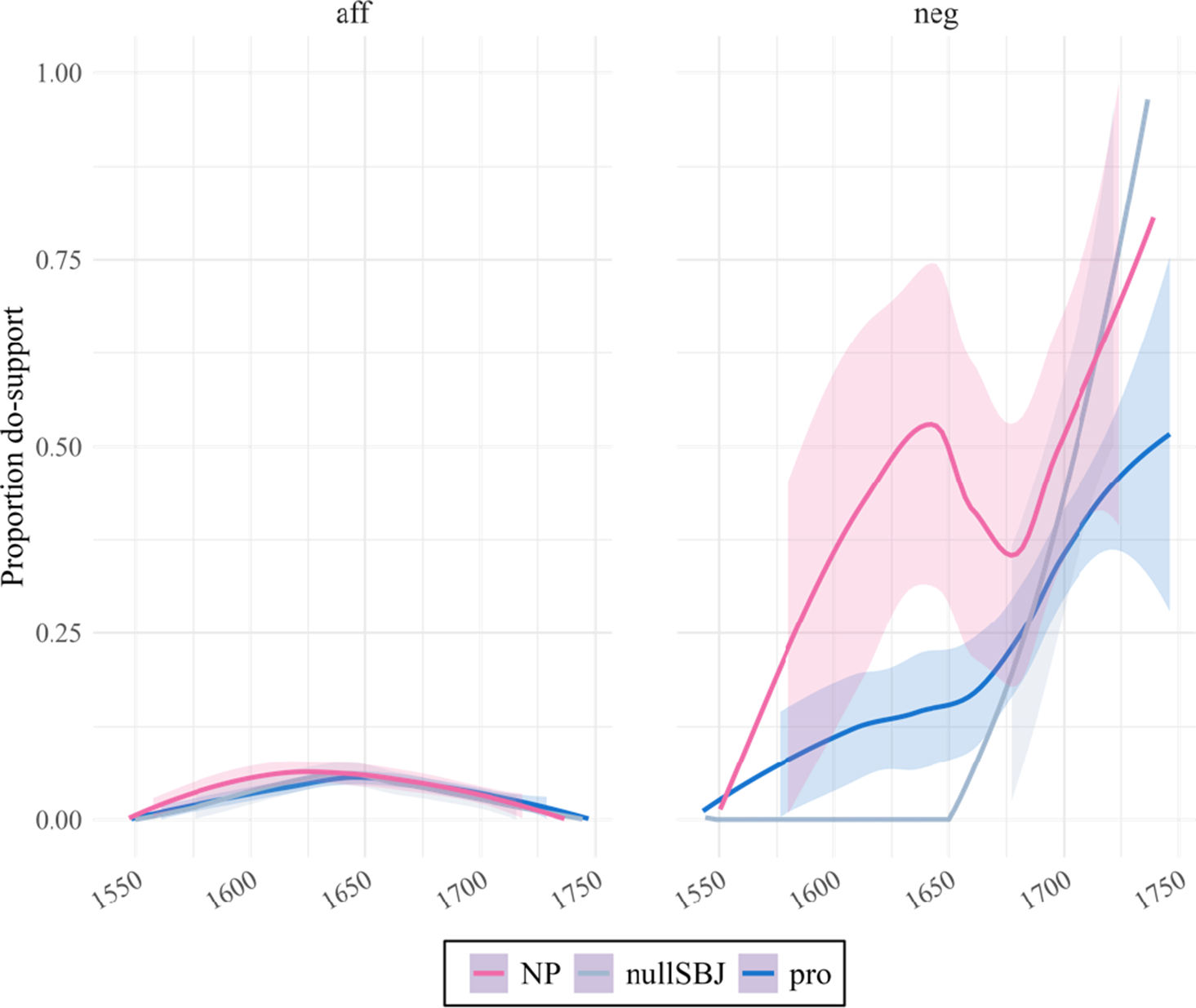

The overall proportions of affirmative and negative declarative do were taken as a starting point before breaking down the results further. The results are in figure 2. Affirmative declarative do is rare, at 3.6 per cent overall proportions (292/16,092). Negative declarative do occurs 140 times out of 522 possible occurrences (26.8 per cent), and remains at approximately 20 per cent during the seventeenth century before a more pronounced increase after 1700, reaching a 60–75 per cent average in the 1720–47 period.

Figure 2. Frequencies of declarative do-support (LOESS curves)

aff = affirmative declarative, neg = negative declarative

6.2 Intermediate do

6.2.1 Argument selection

If early Scots do resembles intermediate do, a higher occurrence with agent-selecting verbs is expected. The results, in figure 3, affirm this prediction for affirmative declarative clauses, where do-support is most frequent with agentive verbs (such as (9a,b)) compared to the other verb classes; there are 53 examples of do-support with agentive verbs, out of 1,110 possible occurrences (constituting c. 18 per cent of the overall frequency of affirmative declarative do-support). Unaccusative verbs only appear with affirmative declarative do-support 8/848 times in total, and the know class 29/1,856 times.

Figure 3. Frequencies of do-support by verb class (loess curves)

ag = agentive, unacc = unaccusative

The findings for negative declarative do are less easily interpretable. Results for agentive and know-class verbs, as in (10a,b), are more robust from the later seventeenth century, when do-support frequencies sharply increase with both verb types and agentive verbs have an apparent advantage. Before this point, there is insufficient data to draw reliable conclusions about the difference between the verb types; the curve for unaccusative verbs is based on 44 clause tokens, and only 8 of these have do-support: come (2), go (2), stay (2), live (1), stand (1).

The unaccusative verbs with affirmative declarative do-support, as in (11a,b), are come (3), stay (3), go (1), lie (1). These verbs are mid-high on Sorace’s (Reference Sorace2000) Unaccusativity Hierarchy, and thus not expected to show agentive qualities. However, as Ecay (Reference Ecay2015: 80) notes, the function of do could be to coerce agentivity on non-agentive verbs in these cases, i.e. do is used to indicate an external argument.

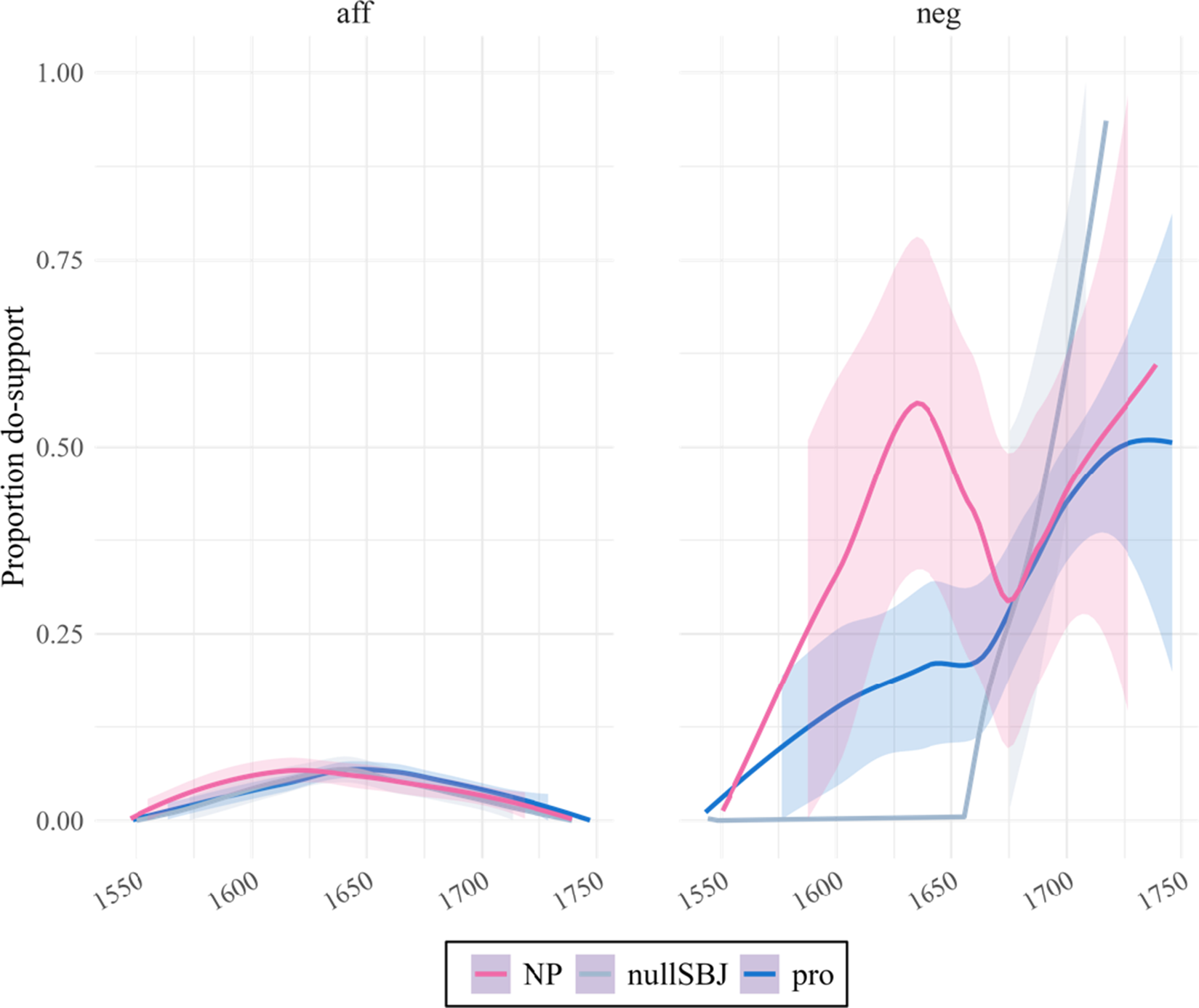

6.2.2 Subject type

Measuring do-support frequencies between pronominal and non-pronominal subjects, no preference is evident in affirmative declarative clauses (see figure 4). In negative declaratives, non-pronominal subjects consistently show higher do-support rates throughout the period, though caution is needed due to their small sample size: 75, of which 30 have do-support.

Figure 4. Frequency of declarative do-support by pronominal or nominal subject (loess curves)

‘NP’ = non-pronominal subject, ‘pro’ = pronominal subject, ‘nullSBJ’ = null subject

Considering the special status of the know-class verbs as hedging devices, their association with first-person subjects, as in (12), might skew the results; pronoun subjects with know-class verbs amounted to 39.4 per cent of the total negative declaratives with pronoun subjects (n=99), and the overall majority of know-class subjects are 1sg, the most likely subject to be used in a hedging function (79 per cent; 1,337/1,689).

The subject type effect was tested again without the know class, seen in figure 5.

Figure 5. Frequency of declarative do-support by pronominal or nominal subject, excluding know-class verbs (loess curves)

‘NP’ = non-pronominal subject, ‘pro’ = pronominal subject, ‘nullSBJ’ = null subject

Excluding the know-class verbs indeed yielded higher proportions of negative declarative do with pronoun subjects, particularly noticeable from the late sixteenth century. These results appear more similar to Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) findings regarding subject type; the effect is there, but fades after a critical point in time – around 1675 in the PCSC data.

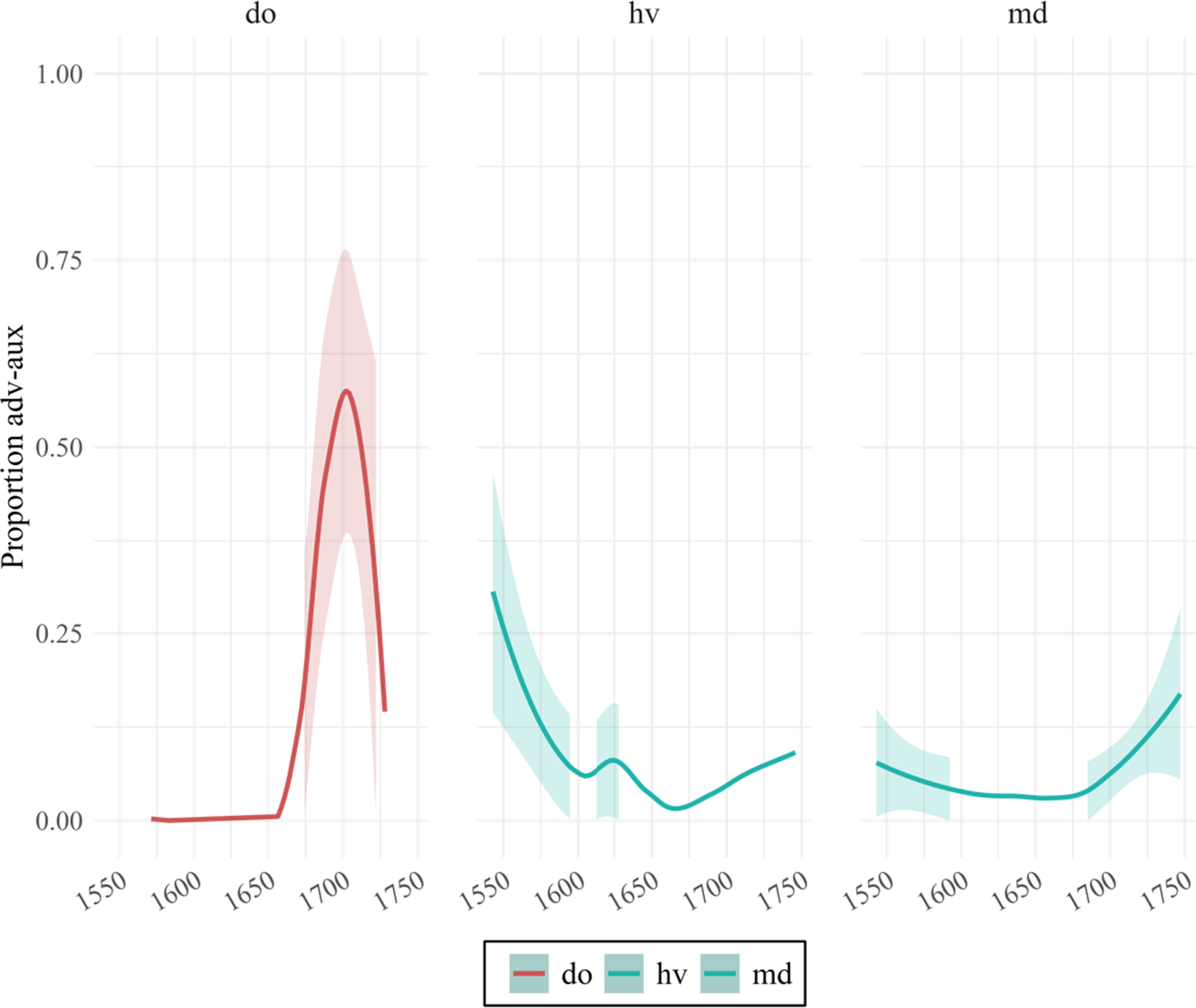

6.2.3 Clause position

Figure 6 shows results for the position of do in relation to mid-clausal adverbs, compared with the position of auxiliary have (‘hv’) and modals (‘md’; e.g. will, shall). The proportions represent instances where adverbs occur between the subject and finite auxiliary/modal (13) compared to when adverbs appear after the verbal item (14); higher proportions suggest that the verbal item occupies the lower clausal position.

Figure 6. Proportions of post-adverbial (vs pre-adverbial) verbs (loess curves)

Results for all modal and auxiliary verbs show inconclusive patterns; on average, modals appear in post-adverbial position 54/544 times, have 19/179 times and do 7/48 times. Have seems to maintain a low position initially, then shifting to a higher position, but data after 1600 is insufficient for definitive conclusions. Modals exhibit low frequencies in post-adverbial position at the start and end of the seventeenth century, with a data gap in the seventeenth century. Despite some noise, the curve for do suggests that it frequently takes a lower position compared to the modals and have.

6.2.4 Summary

In testing whether do-support in the PCSC behaves like intermediate do, the following pattern was found:

-

1. Do-support occurs more with verbs taking agentive subjects than with know-class or unaccusative verbs. This difference is most striking in affirmative declarative clauses, but can be seen after 1675 in negative declarative clauses.

-

2. Do-support occurs more with non-pronominal subjects in negative declarative clauses. When know-class verbs are excluded, this effect is lost after 1675.

-

3. There is no subject type effect on affirmative declarative do-support.

-

4. In the late seventeenth century, do-support occurs post-adverbially more often than other auxiliaries and modals.

Findings 1, 2 and 4 are consistent with Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) observations for intermediate do in English, but 3 is not. Additionally, as Ecay (Reference Ecay2015) observes for English do-support around 1575, some reanalysis seems to take place in negative declarative do around the time when affirmative declarative do-support declines, i.e. around 1675, indicated by findings 2 and 4 for subject type effect and clausal position, but not for the argument-selectional features (finding 1).

7 Discussion: assessing the origin of Scots do

Thomason, broadly defining what kinds of linguistic changes count as contact-induced, states:

Applying this criterion alone to closely related languages like Scots and Southern English is challenging; discerning changes independent of contact after their split from a shared ancestor – namely, independent change towards similar outcomes (i.e. parallel developments) – is notoriously difficult. It is therefore necessary to consider a combination of diagnostic criteria to determine the likelihood of Scots do-support being a transfer from Southern English during anglicisation.

A key diagnostic for contact-induced change was discussed in section 2.1, social context, where it was established that the social environment in the period between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries is conducive to contact-induced syntactic change. Poplack & Levey elaborate on Thomason’s (Reference Thomason2001) criterion in (15), providing more specifications on how a particular feature can be identified as contact-induced (16).

From 1), a timing criterion is established: if a candidate feature is present in Southern English (as the source variety) but not in Scots before the contact event (in this case, anglicisation), it is more likely to be contact-induced. We have observed that do-support emerged in Scots after intense contact with Southern English begins. Moreover, Germanic varieties with less intense contact with English, i.e. Dutch, German and Scandinavian languages, have not developed do-support in the same way as English and Scots (see, e.g., Gotthard (Reference Gotthard2019: 19–20) for a summary) – i.e. the candidate feature is not present in ‘non-contact varieties’. Hence, based on the timing criterion alone, we can identify Scots do-support as a likely contact-induced change as a result of anglicisation.

The second and third criteria in (16), if my interpretation is accurate, may be better understood as related to shared grammaticalisation, as described by Robbeets & Cuyckens (Reference Robbeets and Cuyckens2013): if a candidate feature for contact-induced change is identical to the source language feature in terms of distribution and function, it is likely to be inherited. If the feature differs between the languages in contact, it provides evidence for contact-induced change. This diagnostic has been applied by Colleran (Reference Colleran2017) to assess contact-induced transfer or shared inheritance in common features of Old Frisian and Old English, namely the grammaticalisation of lexical verb aga(n) ‘have’ to deontic auxiliary aga(n) ‘have to’, and the development of having the present participle as verb complement. In Colleran’s (Reference Colleran2017) study, and much of the research that has given rise to these criteria, it is unknown whether the proposed source language (e.g. Old Frisian) originated the candidate feature or if it was inherited from a shared ancestor of both languages. The situation is different for English and Scots in the Early Modern period, as we have a reasonably good idea of which features were common to both languages before the investigated contact scenario. Pa-Tel provides a related diagnostic, useful for establishing the origin of Scots do:

That is, if a candidate feature emerges in the receiving language in its fully grammaticalised form, it is more likely to be a transferred feature. Thus, if the shared grammaticalisation criterion applies, it may indicate that parallel developments, rather than contact, have caused the change. Then, interpreting Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) intermediate do as a true grammaticalisation stage suggests that the change in Scots is most likely internal, as early Scots do exhibits similar behaviour to this English intermediate do stage; while there are some differences between Scots and English (although sample sizes are too small for wholly conclusive results), it is not post-1575 English do which emerges in Scots post-1575.

However, this conclusion comes with some caveats. Firstly, determining if Scots do-support fits the criterion relies on our interpretation of intermediate do – whether it is genuinely ‘intermediate’, a grammaticalisation stage in the development of modern do-support, or whether it is a distinct grammar yielding to the dummy-do grammar, a grammatical system which became reanalysed into the modern system. If the latter, the PCSC data might indicate the earlier grammar being introduced to Scots from English through contact or geographical diffusion. Therefore, caution is needed when assessing the overall timing of the change in English, compared with the PCSC data. Crucially, Ellegård (Reference Ellegård1953) does not use correspondence data, and Nurmi’s (Reference Nurmi1999, Reference Nurmi, Taavitsainen, Melchers and Pahta2000, Reference Nurmi, Kastovsky and Mettinger2011) findings from the CEEC suggest a later reanalysis of do in English compared to Ellegård’s (Reference Ellegård1953) corpus. Nurmi’s results may also indicate a northward diffusion of the intermediate do grammar, as affirmative declarative do declined later in the North than in Southern dialects – in Ecay’s (Reference Ecay2015) analysis, the existence of affirmative declarative do is diagnostic of the intermediate do grammar. As has been established, in analysing contact between Scots and English, regional variation matters: pre-1560, Scots was in convergence contact with Northern dialects, post-1560 Scots was in substrate-superstrate contact with Southern English. Further insight into do-support in Northern English dialects may elucidate what we observe in the Scots data. Finally, the difference in Southern English and Scots writing observed in these results could also reflect variations in spoken versus written styles, impacting our interpretation of do’s emergence in Scots – whether a transfer between speakers, or an adaptation of a written norm.

8 Conclusions

The findings of this study corroborate previous research in dating the rise and regulation of Scots do-support as starting from the late sixteenth century. In investigating the research question, the analysis reveals that seventeenth-century Scots do-support in the PCSC is akin to ‘intermediate do’ in English, as investigated by Ecay (Reference Ecay2015). Notably, similarities include do occurring more frequently with verbs selecting agentive subjects, compared to know-class and unaccusative verbs, and with non-pronominal subjects compared to pronoun subjects. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, a similar upward trend in do usage, observed a century earlier in English, is evident in the PCSC data. This is noticeable only in contexts favouring do-support; for instance, it is present for pronoun subjects when excluding the know-class, which tends to discourage do-support with these subjects. After the c.1675 bump, do-support rapidly increases in all contexts.

When evaluating the emergence of Scots do-support, much of the evidence presented in sections 2 and 7 supports it being an anglicisation outcome: the theory of an independent development of Scots do does not adequately explain why this development, along with the loss of verb-raising facilitating the regulation of do, occurs almost 200 years later in Scots than in English, during a period of intense contact between Scots and Southern English, which already exhibited a modern type of do grammar. However, the presence of intermediate do qualities in the early Scots do-support auxiliary complicates such an analysis, assuming it truly represents an intermediate stage in the grammaticalisation of do. Instead, the findings here may suggest a northward diffusion of intermediate do, which would account for the reported time lag between the emergence of do-support in English and Scots. Future research should explore dialectal or genre differences in the development of English and Scots do, to shed more light on the emergence of Scots do-support. For now, it can be concluded that do-support is a feature which we should be hesitant to call an anglicisation-induced change in Scots.