INTRODUCTION

Racial residential segregation has been the linchpin for racial stratification in the United States (Bobo Reference Bobo1989; Massey Reference Massey1995). Segregating African Americans effectively denied them equal educational opportunities, minimized their employment opportunities, diminished their political clout, and constrained their ability to accumulate wealth. No metropolitan area displayed how segregation led to racial stratification more clearly than Detroit. The spatial mismatch hypothesis was developed from observations of Detroit’s segregation: expanding job opportunities in the suburbs after 1950 while Blacks were confined to the city (Kain Reference Kain1968). The litigation that overturned Brown v. Board of Education (1954) by ruling that the principal of neighborhood schools trumped the principal of integrated schools came from Detroit (Milliken v. Bradley 1974). Metropolitan Detroit came to be the epitome of American Apartheid in 1990 when African Americans made up 77% of the city’s residents while 93% of the suburban residents were White.

Those who study segregation may be surprised by changes happening in Detroit since 1990, namely a peaceful exodus of African Americans from the city to the formerly White suburban ring. By 2019, 45% of the metropolitan African American population lived in the not-so-segregated suburban ring. And, since the end of the city’s bankruptcy in 2014, which is described later, substantial investments have been made in improving the quality of life in the city. The exodus of Blacks has slowed and the city’s White population has grown.Footnote 1

This essay explains how metropolitan Detroit gave rise to the song played on soul music stations fifty years ago, “Chocolate City; Vanilla Suburbs” (1975) and why there was a Black exodus to the suburban ring. Decreases in racial segregation in neighborhoods and schools are documented and information is provided about the post-bankruptcy efforts to turn Detroit into a city that offers employment and residential opportunities to a diverse population.

THE EMERGENCE OF RACIAL RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION

Racial residential segregation emerged slowly in the cities of the Midwest. A few Black migrants arrived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For the most part, they shared neighborhoods with European immigrants. The African American population grew rapidly when southern Blacks moved to industrial centers to fill the demand for labor during World War I. A thorough system of racial segregation in neighborhoods and schools was quickly established, abated in part by the Supreme Court’s Corrigan v. Buckley (1926) decision. This upheld an owner’s right to add a covenant to a property deed specifying that it might never be owned or occupied by a person of “Black race or blood.” As Olivier Zunz (Reference Zunz1982) summarized in his history of Detroit, Blacks lived urban history in reverse. European immigrants were highly segregated upon arrival but gradually were assimilated into native White neighborhoods. Blacks, au contraire, as their numbers grew, were increasingly and thoroughly segregated from Whites.

Enforcing residential segregation became easier in the Depression decade. The federal government-initiated programs to insure home mortgages, allowing people to stay in their homes or buy a new one. The Federal Housing Agency encouraged local officials to draw color-coded maps indicating the credit worthiness of neighborhoods (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017). Neighborhoods with Black residents or near Black residential areas were coded red, meaning they were excluded from federal mortgage guarantees. Detroit’s economy improved in 1940 as the city’s factories began producing munitions for World War II. Real estate promoters saw an opportunity and a developer began constructing modest homes in northwest Detroit. However, there was a one-square-mile enclave of Blacks living nearby making the developer’s homes ineligible for federally insured mortgages. To satisfy the Federal Housing Administration, the developer constructed a half-mile long, six-foot-high wall south from Eight Mile Road to clearly delineate his White neighborhood from the Black neighborhood across the street (Van Dusen Reference Van Dusen2019). This satisfied the Federal Housing Agency (Faber and Sucsy, Reference Faber and Sucsy2021). In the following decades, dozens of strategies and policies were developed to ensure that Whites and Blacks would not share neighborhoods in metropolitan Detroit.

The African American population of metropolitan Detroit (Macomb, Oakland, and Wayne counties) more than doubled from 170,000 in 1940 to 350,000 a decade later. Realizing that defense employment was booming but Blacks were often excluded, A. Philip Randolph, in early 1941, began organizing a July 4th march of 100,000 on Washington to demand equal opportunities for African Americans. Fearing violence that would thwart his efforts to gain support for a European war, President Roosevelt responded with Executive Order #8802 in June 1941. The Order mandated there be no racial discrimination in defense industries or government employment, no racial differences in pay for workers who performed identical jobs, and equal opportunities for promotions. Detroit’s active civil rights organization insisted that be carried out. In the 1940s, there was a great need to house Detroit’s rapidly growing Black population. Thanks to booming defense industry employment and equal pay rates, an increasingly large share of African Americans could afford homes outside the inner-city neighborhoods where they were confined.

After World War II, Whites in Detroit and suburban leaders realized that many African Americans had the resources to purchase better quality homes in neighborhoods with amenities and strongly desired to do so. It took a great deal of planning and effort to maintain the Detroit suburban ring for Whites only.

STRATEGIES TO KEEP THE SUBURBS WHITE

Orville Hubbard served as mayor of Detroit’s prosperous Dearborn suburb from 1941 to 1973. He became the nationally known symbol of unalterable suburban resistance to integration. During World War II, he thwarted efforts of the government to build housing for defense workers in Dearborn, although upward of 25,000 African Americans produced armaments at Ford’s factories there (Galster Reference Galster2012). After World War II, the John Hancock Life Insurance Company sought to invest in a residential-commercial development providing upscale new homes for as many as 45,000 in Dearborn (Baugh Reference Baugh2011). Hubbard blocked that fearing the firm would be “weak” about preserving the racial purity of his suburb (Freund Reference Freund2007; Good Reference Good1989). All of the suburb’s vehicles displayed the slogan, “Keep Dearborn Clean” which was interpreted by almost everyone as “Keep Dearborn White” (Hinton Reference Hinton2021). In 1948, Hubbard’s administration financed the building of a 600-acre park for residents thirty-five miles northwest of the suburb so his constituents would not have to go to Detroit’s beautiful Belle Isle park where they might rub shoulders with African Americans. As he explained to a reporter for the Montgomery (Alabama) Advertiser, who interviewed him to see how Dearborn could remain all-White fifteen years after World War II, Hubbard said: “I am for complete segregation, one million percent on all levels,” (Good Reference Good1989, p. 263).

In 1945, recognizing the threat economically secure African Americans posed, officials in the five Grosse Pointe suburbs adjoining Detroit agreed to an innovative and explicit policy to make sure only Christian Whites resided there. Anyone seeking to buy a home in the Pointes had to be interviewed by three local brokers. Then a private detective was hired to prepare a dossier about the candidate. These materials were then given to an unnamed group of three local brokers. They assigned a numerical score to the prospective homeowner. Eastern and southern Europeans had to have higher scores than northern Europeans to purchase a home. Asians, Jews, and African American applicants were automatically assigned a score of zero, preventing them from purchasing a home (Fine Reference Fine1997; Thomas Reference Thomas1966). In 1958, Michigan’s governor Mennen Williams sought to end the Grosse Pointe strategy by denying real estate licenses to brokers who participated in discriminatory practices. The Grosse Pointes successfully challenged that in the courts but in 1966 two African Americans were finally allowed to purchase homes in Grosse Pointe.

After World War II, many African Americans sought homes commensurate with their economic status. Thomas Sugrue (Reference Sugrue1996) explains why high levels of segregation persisted in the city of Detroit after World War II. Blacks sought to move into White neighborhoods and an active Civil Rights Movement defended their efforts. Indeed, one of the African American plaintiffs whose litigation led the Supreme Court to overturn restrictive covenants in 1948 (Shelley v. Kraemer 1948) was the McGhee family who lived in a home with a restrictive covenant on Seebalt Street in Detroit. With the disappearance of restrictive covenants, the active Civil Rights Movement in Detroit pushed for housing opportunities. At the time, the largest and most active chapters of the Urban League and the NAACP were in Detroit. At one point after World War II, the Detroit chapter of the NAACP had 18,000 members. As Sugrue (Reference Sugrue1996) explains, the push for better housing on the part of Blacks went hand-in-hand with real estate brokers who engaged in block busting. Brokers would tell local Whites that Blacks were soon to move into their neighborhood. Then the brokers could purchase homes from Whites at a discount and profitably resell them to African Americans.

Many Whites quickly found a way to avoid the conflicts over neighborhoods that raged in Detroit neighborhoods. The federal government’s housing programs after World War II supported the construction of millions of new homes. In metropolitan Detroit, most were built in the suburbs since vacant land within the city was scarce.

Perhaps there was no metropolitan area in the county where suburban opposition to integration was as massive and consistent as in metropolitan Detroit. As a result, when data were analyzed from censuses 1950 through 1980, Detroit ranked with Chicago, Cleveland, and Milwaukee as the nation’s most segregated metropolises (Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1993; Taeuber and Taeuber, Reference Taeuber and Taeuber1965).

The three-county Detroit suburban ring includes 114 distinct municipalities, each with the authority to tax and the obligation to provide city services. After World War II, they competed with one another to attract manufacturing plants, shopping centers, and residential developments. Because its land was already occupied, the city could hardly enter this competition. While the suburbs competed with each other, there was consensus that Blacks should be excluded. Rose Helper (Reference Helper1969), in the 1950s, sought to determine why African Americans were not moving into the rapidly growing suburbs where government-financed homes were readily available. After interviewing brokers in the New York and Chicago suburbs, she reported that brokers firmly believed that White suburbanites opposed integration because they associated Black neighborhoods with squalor, dirt, vice, and stealing. Even more importantly, the brokers contended White suburbanites wanted no Blacks in their neighborhoods since they assumed school integration inevitably meant a sharp decline in the quality of education.

From the end of World War II until well after passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, suburban leaders in the Detroit suburban ring, consistently stressed that Blacks were not welcome to live in their communities. Detroit’s racial violence in the summer of 1967 that left forty-three dead may have confirmed stereotypes that suburbanites held about African Americans (Fine Reference Fine2007). After that violence, Dearborn Mayor Hubbard encouraged his constituents to “learn to shoot, shoot straight and be a dead shot,” and funded a course to teach housewives how to use shotguns, handguns, and rifles (Serrin Reference Serrin1969).

Some African Americans dared to move to the White suburbs. In 1957, a Black man moved into Dearborn. Mayor Hubbard promptly had his gas line turned off and refused to pick up trash at his house. He left. In 1964, an African American family pioneered in Sterling Heights and purchased a home in that now-integrated suburb. Arsonists torched their home before they could move in (Baugh Reference Baugh2011). Just a month before the 1967 violence, Carado Bailey, an African American Vietnam veteran with a White wife, became the first Black homeowner in Warren. For three nights, angry mobs pelted the home. The police prevented mayhem but arrested none of the perpetrators (Fine Reference Fine2007; Killeen Reference Killeen2018). The Bailey family moved away but returned several weeks later and kept to themselves. Quite likely such incidents were few in number because African Americans understood the extreme hostility they would face in Detroit suburbs. A 1968 report of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission concluded “…that nearly all attempts by Black families to move to Detroit’s suburbs have been met by violence” (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017, p. 147).

Despite the history of extreme racial hostility, African Americans after 1990 moved from the city of Detroit into the suburban ring in substantial numbers without conflict. Rather than replicating the segregation patterns of the city, segregation scores for the entire suburban ring and for the larger suburbs are moderate. For the most part, Black and White students in the suburbs attend the same public schools. Residential segregation has slowly but steadily declined in recent decades (Glaeser and Vigdor, Reference Glaeser and Vigdor2012). This essay describes what happened and why in what was formerly the nation’s quintessential American Apartheid metropolis (Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1993).

OVERARCHING DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS AND THEIR LINKS TO SEGREGATION

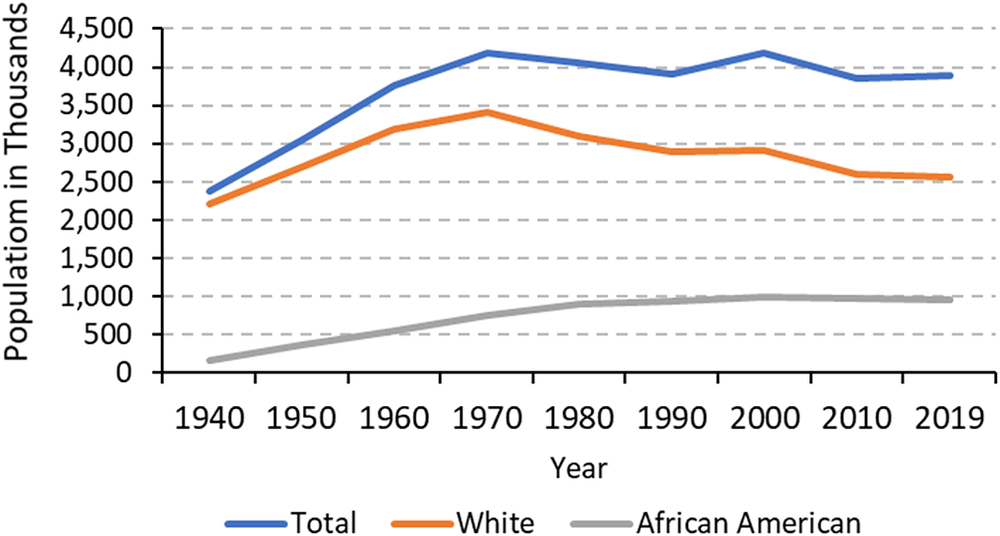

Metropolitan Detroit, as defined for this essay, includes Macomb, Oakland, and Wayne counties. The suburban ring includes the large fraction of Wayne County outside the city of Detroit and the two suburban counties. Figure 1 describes the rapid growth of the metropolis.

Fig. 1. Population of Metropolitan Detroit by Race: 1940 to 2019 (in Thousands)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1940, initiated a “lend-lease” program to supply the British with the arms they needed to hold off German attacks. In his “fireside chat” on December 29, 1940, Roosevelt labeled Detroit the “Arsenal of Democracy” since he knew that tanks, trucks, planes, jeeps, and engines for ships requisite for saving democracy would be built in Detroit (Baime Reference Baime2014). As a result, the area’s population grew rapidly during World War II and for a quarter century after V-J Day. Industrial output boomed. Indeed, by 1950, almost one-half of the world’s production of cars and trucks occurred in the greater Detroit area. The metropolitan population peaked at 4.2 million in 1970 but then stagnated. The metropolitan White population, due to substantial out-migration and low birth rates, was almost one million lower in 2019 than forty-nine years earlier. The African American population peaked in 2000 but is now also declining, losing about five percent since the turn of the millennium. To a large degree, the population decline is attributable to changes in the vehicle industry. The producers in Detroit not only lost market share but also cut production costs by a steady increase in labor productivity. For a quarter century, labor productivity in the vehicle industry has steadily increased at about four percent annually (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2021). The number of production workers has steadily declined.

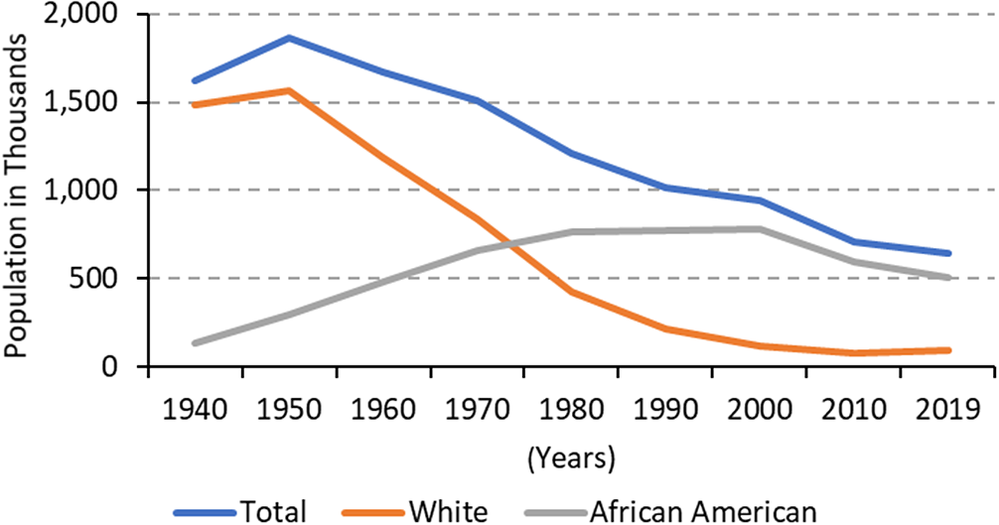

The city of Detroit annexed no land since the 1920s. Figure 2 reveals population trends in the city. Thanks to serving as the “Arsenal of Democracy”, the population peaked at just under two million in 1950 when Detroit was the nation’s fourth largest city. Decline has been the norm since then. In 2019, Detroit’s population was just thirty-five percent of what it was in 1950. The White population fell rapidly and, in 2010, the number of White residents in the city was only five percent what it was in 1950. The African American population grew until 1990 but has steadily decreased since then. The city lost a spectacular share of population in the first decade of this century: one-quarter of its residents in just one decade.

Fig. 2. Population of the City of Detroit by Race: 1940 to 2019 (In Thousands)

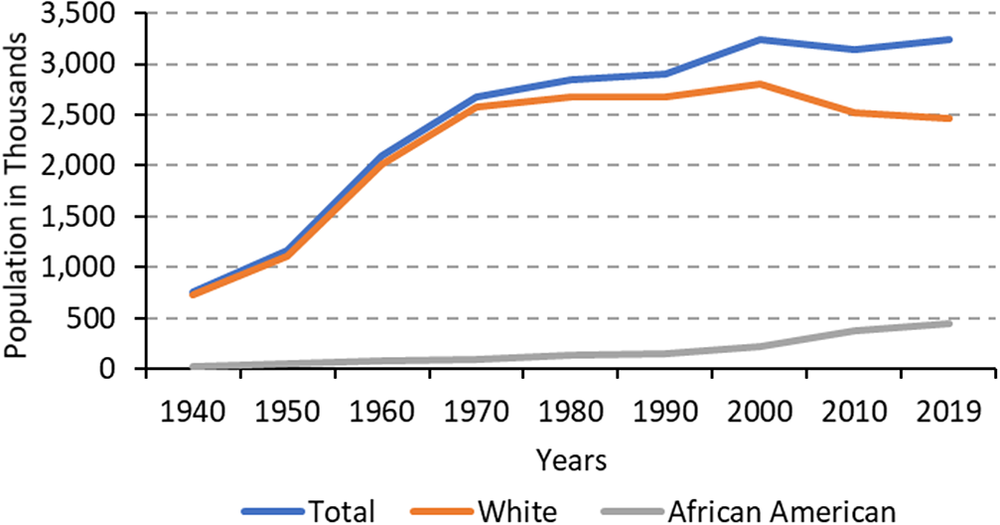

Figure 3 reports demographic trends in the suburbs. This suburban ring includes a few older industrial cities that emerged in the nineteenth century and some places contiguous to the city that grew in the 1920s. As a consequence, there were about three quarters of a million suburban residents in 1940. The federal government’s post-World War II housing policies and the funding of expressways in the Eisenhower era explain why the suburban population ascended to two and one-half million by 1960 (Jackson Reference Jackson1985; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017). The suburbs have grown slowly since the 1980s. But there has been a major racial change. The White suburban population has been declining for almost a half century but the African American population began to increase after 1990 as the barriers that once preserved suburban racial purity gradually fell. Were it not for an influx of Black residents, suburban governments would now be facing the huge challenges resulting from rapid population decline.

Fig. 3. Population of the Detroit Suburban Ring by Race: 1940 to 2019 (In Thousands)

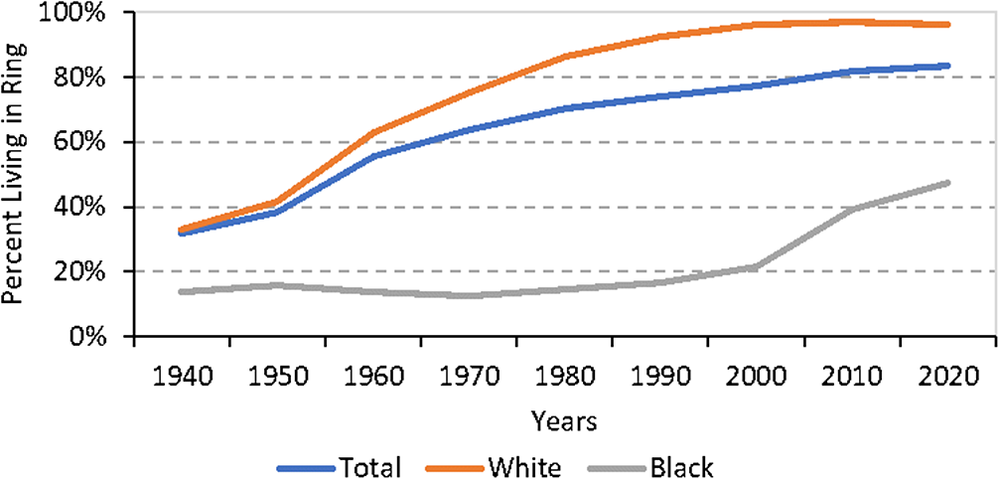

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, about one-third of the metropolitan White population had suburban addresses, as shown in Figure 4. This increased sharply during and after World War II, reaching a peak of ninety-eight percent living in the ring in 2010. But the important story concerns the changing representation of African Americans. There were modest numbers of Blacks living in the suburban ring since World War I. Several locations now in the suburban ring were once independent manufacturing centers, including Pontiac and Mount Clemens and downriver suburbs where factories were built in the late nineteenth century. During World War I, these suburbs attracted African American defense workers. In most, strict segregation was the rule. In Ecorse and River Rogue, for example, railroad tracks separated the Black side of town from the White. There were a few other suburban enclaves of African Americans. In Ecorse, Inkster, River Rouge, Royal Oak Township, and Westland the federal government hastily constructed housing for defense workers in World War II on a racially segregated basis so their Black populations grew (Wiese Reference Wiese2005). And the small community of Romulus has had Black residents since the 1850s when it provided safe houses for the Underground Railroad. Almost 100,000 African Americans lived in the suburbs in 1970 but they lived in segregated enclaves.

Fig. 4. Percent of Total, White and Black Residents Living in the Suburban Ring: 1940 to 2019

The major change revealed in Figure 4 is the growth of the Black suburban population. Between 1990 and 2019, the city’s African American population declined by 269,000. The suburban African American population increased by nearly the same number: 297,000. As a consequence, by 2019 just under one half of African Americans in metropolitan Detroit were suburbanites. The Black population in the suburban ring in 2019 approached one-half million. In that year, only ten cities across the nation had larger African American populations than the Detroit suburban ring.

This demographic shift raises several questions. First, why did the suburban ring become open to African Americans late in the last century? Second, why was there a rapid movement of African Americans from the city to the suburbs? Third, did the migration of Blacks to the suburbs lead to residential integration?

HOW AND WHY DID THE SUBURBS BECOME OPEN TO AFRICAN AMERICANS?

No matter how highly motivated, until recently an African American in Detroit would have paused before renting or buying in the ring with the exception of the Black enclaves. Five changes contributed to the waning of American Apartheid in metropolitan Detroit. First, the racial attitudes of Whites liberalized. My colleagues and I conducted studies of the racial views of Detroit area residents three times. Though the last study was conducted in 2004, nevertheless the percent of a random sample of metropolitan area Whites who said they would move away if just one Black family moved into their neighborhood declined from 24% in 1976 to 8% in 2004. The percent of Whites who said that, if they were searching for a new home and found an attractive, affordable home, they would consider purchasing it even if one-third of their future neighbors were African Americans, increased from 50% in 1976 to 70% in the most recent survey (Farley Reference Farley2011). Data from the General Social Survey corroborate Detroit findings (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Davern, Freese and Morgan1972–2018). When a national sample of Whites was first asked, in 1973, if Whites had a right to keep Blacks out of their neighborhood and that Blacks should recognize that right, 37% agreed (Schuman et al., Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997). When that question was last asked in 1993, only 15% agreed. White respondents were asked how they would vote on a proposed local ordinance. One choice would be to support a measure that would give a homeowner complete authority to sell to whomever he or she wished. The other option would prevent discrimination in home sales on the basis of race or ethnicity. In 1973, only 34% of Whites said they would vote for the “no discrimination” ordinance; in 2018; 77% said they would vote for “no discrimination” (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Davern, Freese and Morgan1972–2018).

Second, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 had an impact by changing the practices of real estate brokers. Presumably, real estate brokers became aware of their duty to treat all prospective customers similarly and that they might be punished for blatant discrimination. Fair housing organizations in south east Michigan have been active in making sure open housing laws are enforced. When Governor Williams established a Michigan Committee on Civil Rights in 1949, he stressed that segregated housing was a civil rights issue (Fine Reference Fine1997). It is challenging to quantify declines in racial discrimination in the sale or rental of housing, but studies suggest a decrease in metropolitan Detroit. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has tested for racial discrimination in metropolitan Detroit’s housing market four times since 1968. They confirm a substantial decline—but certainly not an elimination—in racial discrimination by brokers. The most recent survey, 2012, used paired testers to assess thirty-nine types of discrimination against African Americans who sought to rent advertised units in metropolitan Detroit. There was no significant racial difference on thirty-three of the thirty-nine dimensions (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Levy, Wissoker, Pitingolo and Santos2013).

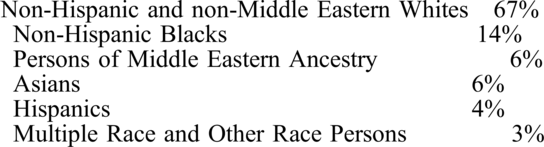

Third, the suburban ring is now much more diverse than in the past. James Loewen (Reference Loewen2005), in his study of Sundown Cities, argues that when Blacks are the only minority group it is straightforward to keep them out of a neighborhood. But it is more challenging to segregate one race when they are one of several non-European groups competing for housing, an observation corroborated by Richard Alba (Reference Alba2020). Once Hispanics, Asians, and Middle Easterners entered the Detroit housing market in substantial numbers, it became more challenging to maintain White racial purity. In 1970, 99.6% of the Detroit suburban population identified themselves as either White or Black. It is different now. The composition in 2019 is shown below.

It may be difficult to maintain a color line when a third of the population is not from the European groups that demographically dominated Detroit for three centuries.

Finally, market forces abetted the integration of the suburbs. After the 1970s, the demand for housing in the suburbs fell sharply. The White population of the ring declined by nearly a quarter million from 1970 to 2019. Forty-five of the 114 Detroit suburbs lost population in that interval. This likely motivated suburban officials and real estate brokers to appreciate an influx of middle- and upper-income residents from the city who had the funds to purchase or rent suburban residences. That in-migration helped to stave off the numerous problems resulting from declining populations and plummeting tax bases. In several suburbs, younger African American are replacing older Whites which not only reduces segregation but keeps the suburbs’ population and tax base stable and also maintains enrollment in suburban schools. The operation of local public schools in Michigan is no longer primarily financed by local property taxes. Local school districts obtain operating funds from the state which allocates $8,100 per student enrolled (Michigan 2021b). School officials are highly motivated to make sure their districts attract students, giving suburbs another incentive to welcome newcomers from the city of Detroit and elsewhere.

WHAT PROMPTED DETROIT’S AFRICAN AMERICANS TO MOVE TO THE SUBURBS?

Bill Frey (Reference Frey2015), in his popular Diversity Explosion book, brought attention to the recent substantial increase in Black suburbanization. He observed that the Black populations of most of the nation’s largest cities declined after 2000 but that there was a corresponding rise in African American populations in the suburbs. Frey showed that this suburban migration was led by prosperous Blacks and by married-couple households.Footnote 2 His findings well describe demographic trends in Detroit; that is, Black out-migration from the city resembles the White out-migration of previous decades.

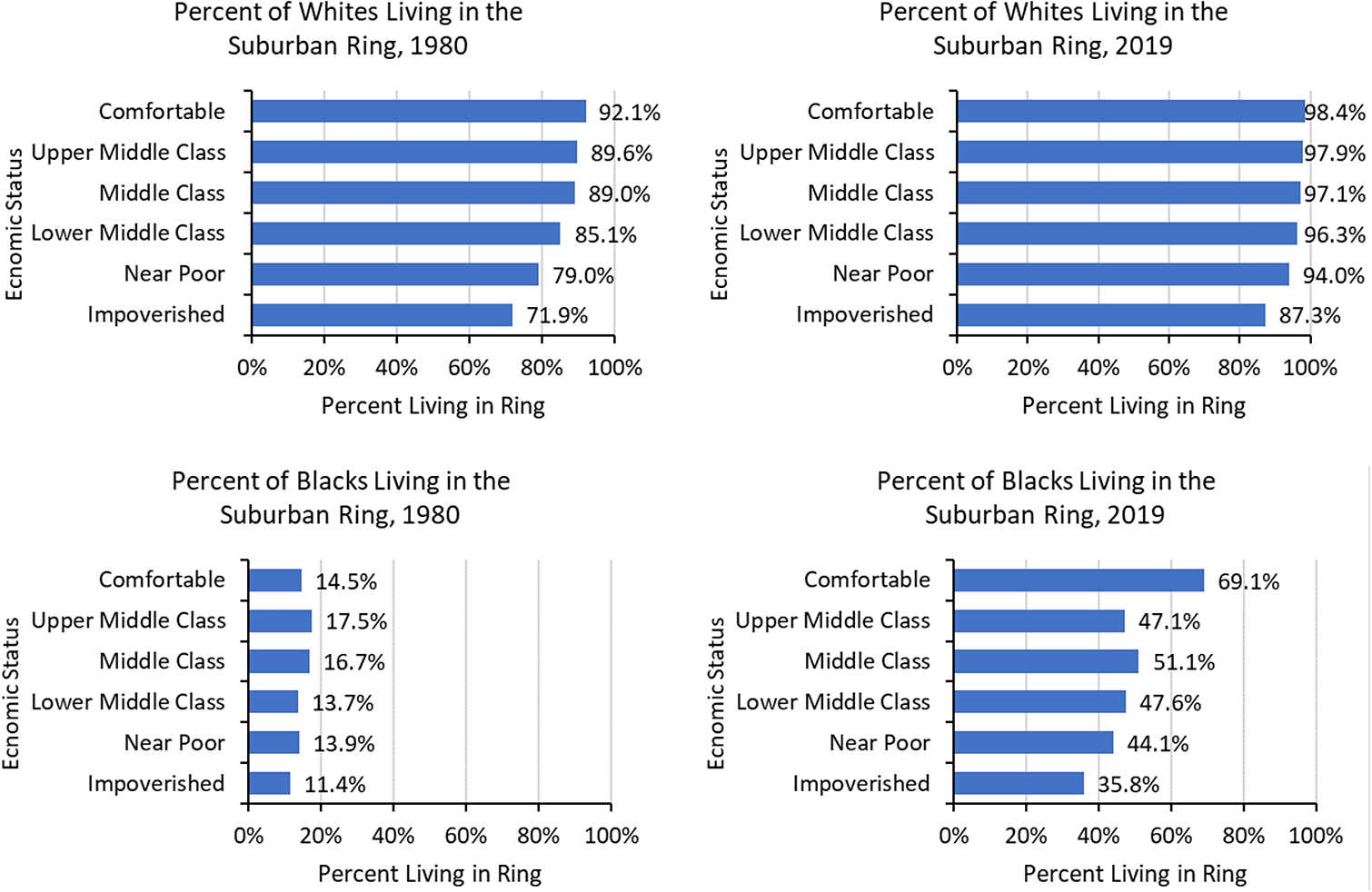

Figure 5 describes what has happened. Whites and African Americans were classified by their economic status as reported in Census 1980 and the 2019 American Community Survey. The Impoverished are those in households with pretax incomes below the poverty line, which was $26,000 for a household of four in 2019. The Near Poor are those in households with incomes 100% to 199% of the poverty line. And the Comfortable are those whose household incomes were five or more times the poverty line or more than $131,000 for a household of four in 2019. Figure 5 shows the percent of each economic group residing in the suburbs, not in the city of Detroit.

Fig. 5. Percent of Metropolitan Area Whites and Blacks, Classified by Economic Status, Living in the Suburban Ring: 1980 and 2019

By 1980, virtually all economically successful Whites in the metropolis had migrated to the ring. However, among metropolitan Whites below the poverty line, one in four remained in the city. A generation later, almost all Whites—98%—were suburban residents. Through the 1980s, Detroit’s version of the Maginot line kept the suburbs White except for a few enclaves. At least since the 1920s, there has been a substantial Black middle and upper class in Detroit (Davis Reference Davis2019; Randall Reference Randall2020; Thomas Reference Thomas1992). They did not have the option of living in the ring before the Fair Housing Act. As Figure 5 shows, African Americans in 1980, regardless of their income, lived in the city. But that changed. By 2019, the majority of middle income and economically comfortable African Americans lived in the suburbs.

Whites moved from the city to the suburbs for a variety of reasons. The government’s housing program that made quality suburban homes available at reasonable cost was a major reason, but as our Detroit surveys and Thomas Sugrue (Reference Sugrue1996) report, a desire to avoid living with Black neighbors was another important reason. The reasons for the current suburbanization of African Americans are similar in some regards but different in others. In brief, Detroit’s suburbs typically offer a higher quality of life with substantially lower taxes and expenses.

There is the issue of taxes. As the city’s tax base declined after 1950, the city raised taxes to maintain services. Detroit is the only city in Michigan with a five percent tax on all utilities. The city also raised property tax to a very high level. Tax rates are, generally, much lower in the suburbs than in Detroit. For example, in 2020, a homeowner in Detroit paid seventy mills per $1,000 of assessed value for his or her home. In Warren the rate was fifty-six mills: in Farmington Hills, forty-one mills and in Sterling Heights and Troy, thirty-seven mills. A few of the suburban Black enclaves, including Highland Park, Ecorse, and River Rouge, impose even higher property taxes than Detroit but they are the exceptions. In Michigan, property tax rates are inversely related to the poverty rate of those who live in the municipality (Michigan Department of Treasury 2021).

During its decades of travail, the city imposed an income tax on residents of 2.4%. Only three of the 114 suburbs impose an income tax, and they are suburbs with a long history of African American neighborhoods: Hamtramck, Highland Park, and Pontiac.

In addition, homeowners in Detroit in recent years paid excessive property taxes. In 2002, in an effort to cut costs, Mayor Dennis Archer laid off the city’s property assessors. The recession that began in 2008, the continued out-migration from the city, and the subprime lending crisis contributed to drastic reductions in the value of homes in Detroit. Michigan law specifies that the assessed value of a home must be fifty percent of its actual sales value but, since there were no assessors, Detroit homeowners from the early 2000s to 2016 paid taxes as if their homes’ value had never dropped. Shortly after becoming mayor, Michael Duggan ordered a reappraisal of property values in Detroit. It was completed several years later and tax bills were reduced by an average of about twenty percent, but residents were never reimbursed for their overpayments which were estimated to be $600 million (Atuahene and Berry, Reference Atuahene and Berry2019).

In addition to high taxes, home and auto insurance rates are much higher in Detroit than in the suburban ring. Indeed, Detroit has the highest car insurance rates in the nation. The average insurance premium for auto owners in Detroit in 2020 was $5,100 while across the state the average cost was only $2,500 (Gibbons Reference Gibbons2021.) An owner of an ordinary car with a good driving record living in Detroit may save about 22% on car insurance by moving to Warren, 29% by moving to Sterling Heights, 32% by moving to Utica, and 41% with a change of address to Canton Township. (ValuePenguin.com 2021).

In addition to the high cost of living in Detroit, suburban public schools are generally seen as more effective than the schools in Detroit. There has been a great awareness of the deficient educational system in the city and numerous reforms have been attempted. Twice the state has taken over the failing Detroit public school system but there were few signs of improvement. In 2017 a new state-funded Detroit Community Schools district replaced the old district. Its leader, Nicholas Vitti, is attempting to thoroughly reform the city’s public schools, but the district faces many challenges. Detroit students, in 2015, had lower average test scores on standardized achievement tests than any other large city (Einhorn Reference Einhorn2018; Lewis Reference Lewis2017). The Great Schools (2021) compilation of data for Michigan districts reported a high school graduation rate of 76% for the city’s schools. Many suburban districts had graduation rates exceeding ninety percent. In the Dearborn, Warren, and Grosse Pointe districts, 95% graduated, 94% in Utica, and 88% in Southfield and Troy. Michigan State professors Joseph T. Darden and Richard W. Thomas (Reference Darden and Thomas2013) argued that Detroit parents who hoped their children would matriculate at the state’s universities should strongly consider a move to the suburban ring. Indeed, only ten percent of the eleventh-grade students in the city’s public high school tested as “college ready” in 2020 (Great Schools 2021).

Crime is another crucial issue. The crime rate has been falling in Detroit and homicides declined to a fifty-year low in 2017 (Dickson Reference Dickson2018). But the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report shows that rates of both property and violent crime are, typically, much lower in the suburbs than in the city. For 2019, the FBI published a violent crime rate of 1967 per 100,000 for Detroit residents. In Warren, the rate was 482 per 100,000; in Dearborn, 325; in Southfield, 266; and 128 per 100,000 in Canton Township (U.S. Department of Justice 2019).

Finally, there is the issue of commuting. After World War II, employment in Detroit plunged as the vehicle firms closed their aging multi-story factories in the city and built new ones on the spacious green fields of suburbia. Later, wholesale trade and then retail trade departed the city for the ring. As a result, most employed people who live in the city of Detroit work in the ring. The Census Bureau (2021) estimated, in 2018, that 72% of employed Detroit residents went to work in the ring. A move to the suburbs would reduce commuting distance for many who live in the city.

DOES SUBURBANIZATION LEAD TO RESIDENTIAL INTEGRATION?

Fifty years ago, Harold Rose (Reference Rose1976), in his definitive book, portrayed Black suburbanization as an expansion of central city ghettos across a city line. Is it appropriate to draw the same conclusion today in metropolitan Detroit with its large Black suburban population?

Since 1950, the index of dissimilarity has been the “work horse” measure of racial residential segregation. The racial composition of component parts of a large geographic area are obtained from a census or the Census Bureau’s annual estimates of racial composition. If the ratio of Black to White residents were identical in each and every component part, there would be no segregation and the index for the large geographic area would approach its minimum value of zero. Were apartheid so thorough that every component part of the large area were exclusively White or exclusively Black, segregation would be complete and the index takes on its maximum value of 100 (Duncan and Duncan, Reference Duncan and Duncan1955; Taeuber and Taeuber, Reference Taeuber and Taeuber1965).

If you use the 114 municipal suburban governments as units of analyses, you find that the Black-White index of dissimilarity measuring racial residential segregation for the suburban ring in 1970 was 87. This is a high level of segregation, suggesting that many suburbs were almost all White while a few others were almost all Black, or highly segregated. Ninety-five percent of the suburban African American population in 1970 was concentrated in suburbs that had African American enclaves. By 2019, the similar index of dissimilarity using the identical 114 suburbs had fallen to 55. There is still segregation, but less than there was fifty years ago. In 1970, ninety-five of the 114 suburbs had populations less than one percent African American. In 2019, fifty-nine of them had Black populations exceeding four percent. The suburbanization of African Americans was not a pattern of municipalities “flipping” from one race to the other or the Detroit ghetto crossing the city line.Footnote 3 Rather, by 2019 there is a widespread dispersion of African Americans throughout the ring along with the persistence of a few African Americans suburban enclaves.

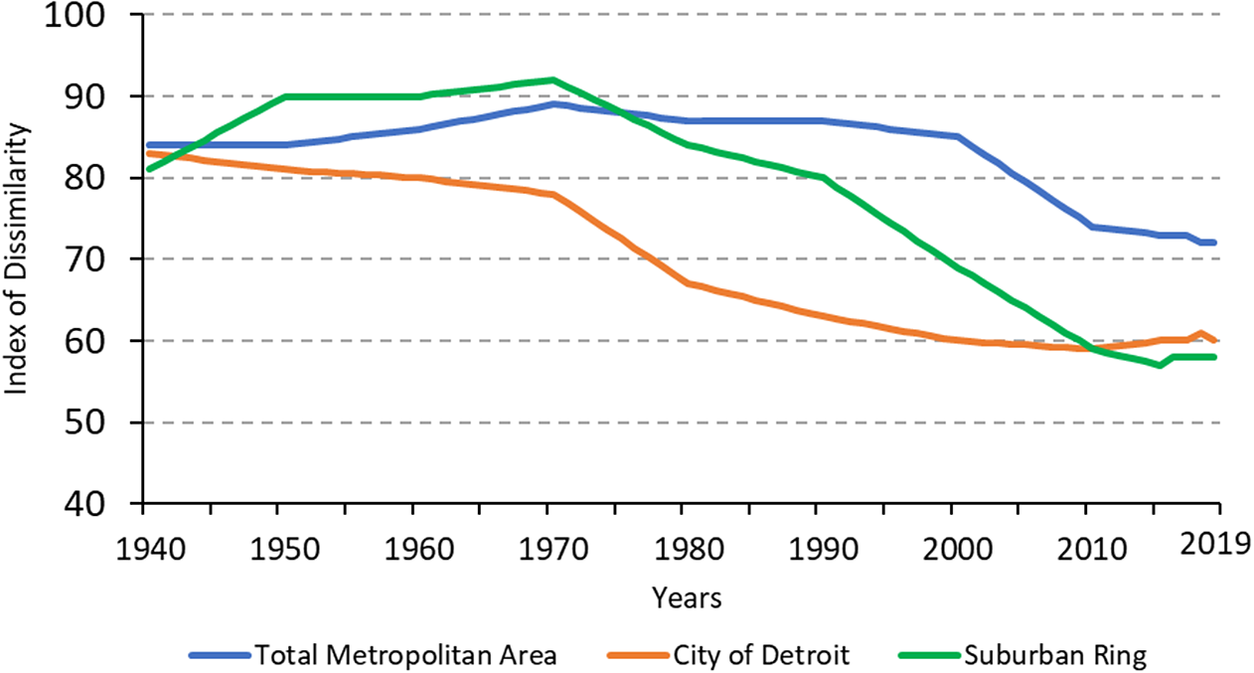

Figure 6 displays indexes of dissimilarity measuring the segregation of Whites from African Americans from Censuses 1940 to 2019. Rather than municipalities, these indexes use neighborhood data. The Census Bureau, since 1940, has reported racial composition for census tracts. These are described as neighborhoods by urban analysts. The most recent tract data are from the concatenated file of the 2015–2019 American Community Survey. In that survey, census tracts in metropolitan Detroit were home to an average of 1300 households and 3300 residents. Segregation trends are shown for the entire metropolitan area, for the suburban ring, and for the city of Detroit. These scores measure whether Blacks and Whites reside in close proximity, but they do not measure social interaction between neighbors.

Fig. 6. Index of Dissimilarity Measuring the Residential Segregation of Whites from Blacks; 1940 to 2019

At the outset of World War II, the segregation score for the ring was 80 but this increased to 90 by 1950. This is explained by growth of the Black population in a few industrial suburbs and the location of segregated Lanham Act housing for Black defense workers in six suburbs. Suburban segregation has been declining since the 1980s and the current index, 58 in 2019, is much lower than 90—what it was in 1960. Segregation has certainly not disappeared, but it has fallen substantially.

The city was most segregated in 1940 and has slowly become more integrated. The biggest declines in segregation within Detroit were in the years when Blacks replaced Whites in numerous neighborhoods. That change occurred rapidly but not instantly, so segregation declines in the city largely reflect the White to Black neighborhood transition. Chicago alderman Francis X. Lawler became famous for his definition of residential integration: the interval between the arrival of the first African American and the departure of the last White. By 2019, the index for city of Detroit had declined to 60 from its maximum of 85 in 1940.

The segregation score for the entire metropolis slowly declined after 1990 but is much greater than for either the city or the ring because of the difference in racial composition of the two areas: 79% African American in the city in 2019; 14% African American in the suburbs.

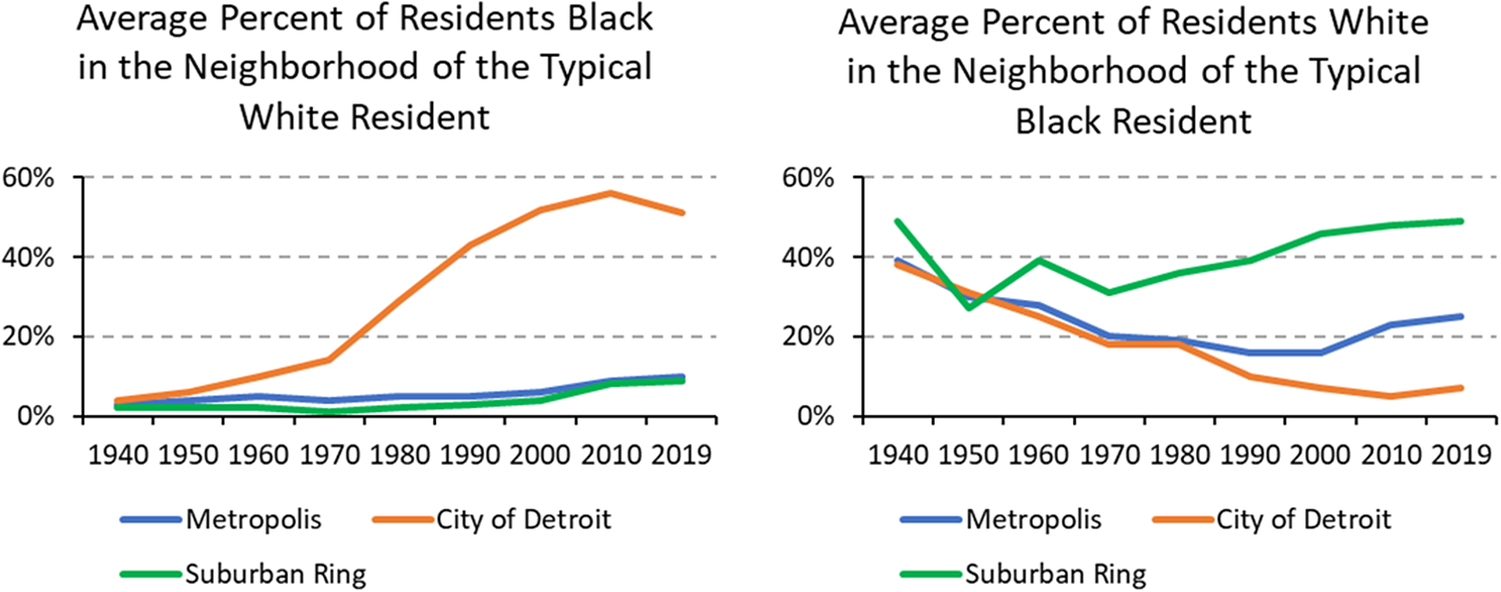

Decreases in segregation can also be monitored by examining changes in the composition of neighborhoods. The left panel in Figure 7 shows the percentage of residents who are Black in the neighborhood of the typical White resident of the metropolis, the city of Detroit and the suburban ring. These were calculated from census tract data from the decennial enumerations and recent American Community Surveys. Since 1970, Blacks have made up about 24% of the metropolis. For the most part, Whites are isolated from Blacks but that is changing. In 1970, metropolitan Whites typically lived in neighborhoods where only 4% of the residents were Black. In the city, it was a higher 14% since many neighborhoods were undergoing rapid racial change. Increasingly, those Whites who remained in the city shared their neighborhoods with African Americans. A similar change occurred for Whites who lived in the suburban ring, especially after 1990. By 2019, suburban Whites typically lived in neighborhoods where 9% of their neighbors were African Americans. Having African American neighbors on your block is no longer rare in Detroit suburbs.

Fig. 7. Average Percent of Residents Black and White in the Neighborhood of the Typical Opposite Race Resident

The right panel shows the percentage of residents who are White in the neighborhood of the typical African American resident of the metropolis, the city, and the suburbs. The percent of White neighbors for central city African Americans steadily went down reaching a minimum—just 5% in 2010—but rose in the most recent decade as Whites returned to the city. In the suburbs, the percent of residents who are White in the neighborhood of the typical Black increased steadily after 1990. By 2019, suburban Blacks lived, on average, in neighborhoods where just about one-half of their neighbors were White.

INTEGRATION IN INDIVIDUAL SUBURBS

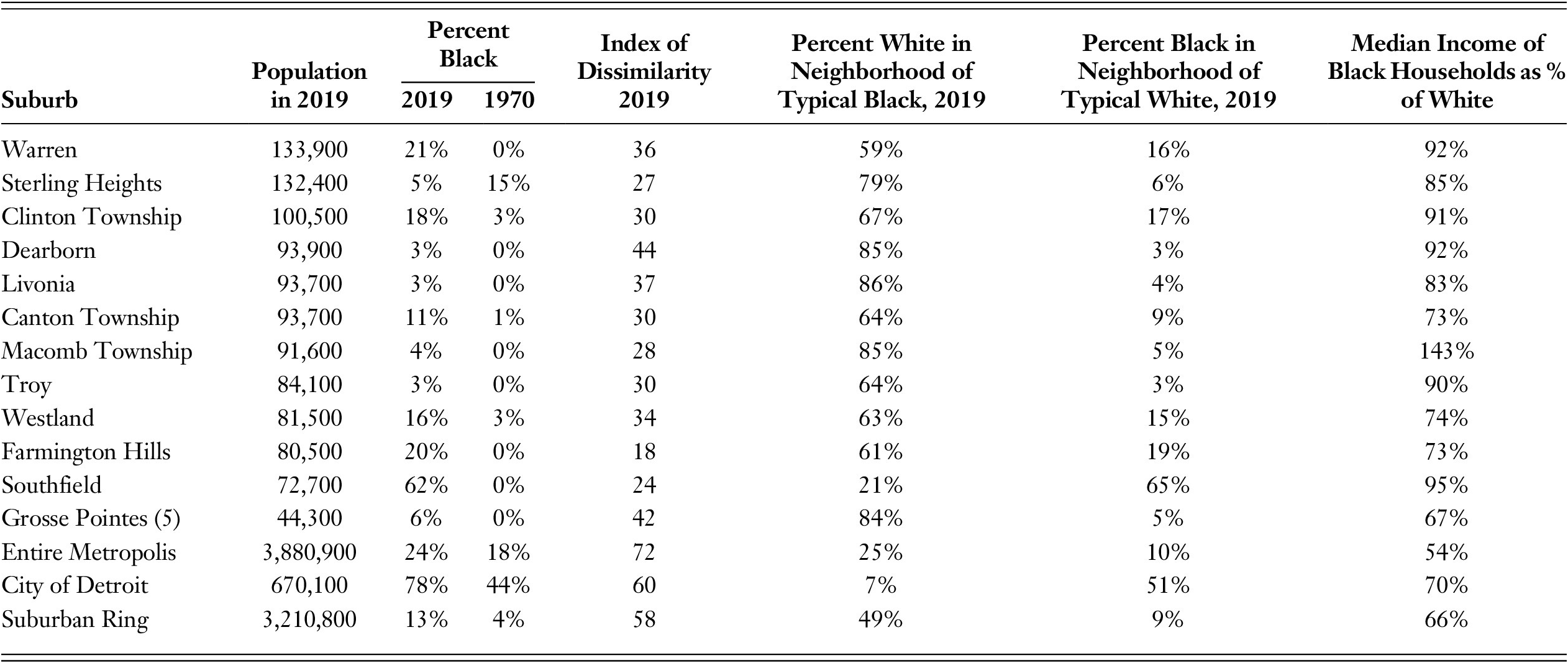

Given historic suburban hostility to integration, I wished to make certain that segregation indexes for the ring were not misleading. To do so, I examined racial composition and neighborhood segregation in the ten largest suburbs of Detroit. I added two additional locations: the five Grosse Pointes, because of their unusual way they enforced segregation, and Southfield—a large and prosperous suburb that recently became majority African American. Table 1 lists each suburb and shows the population as estimated for 2019, the percent African American in 1970 and 2019, and the index of residential segregation within that suburb computed from census tract data. The suburbs ranged in size, in 2019, from 134,000 in Warren to 44,000 in the five Grosse Pointes.

Table 1. Measures of Racial Residential Segregation in a Dozen Largest Detroit Suburbs in 2019 and the Grosse Pointes

In 1970, only two of the thirteen suburbs had Black populations exceeding one percent: Westland and outlying Clinton Township. By 2019, the dozen suburbs had populations that were between 3% and 21%. Southfield stands out as the suburb that went through a substantial transition: only 102 African American residents in 1970 but 51,000 in 2019.

Racial residential segregation scores using census tract data for each suburb are notably low in all of these suburbs. To be sure, the places well known for their efforts to keep African Americans out—the Grosse Pointes and Dearborn—had segregation scores just over 40. Most demographers consider that a moderate score. Five of the thirteen suburbs had low segregation scores; that is, 30 or lower. Prosperous Farmington Hills, where one in five of the 80,000 residents identified as African American, had a segregation score of just 18. Whether African Americans made up a large share of the population as in Southfield or a small percentage as in Sterling Heights and Dearborn, the segregation scores were moderate. Southfield merits comments. The Census has never asked a religious question but those who analyzed Detroit area trends commented that, by 1970, Southfield was the demographic heartland of Detroit’s large Jewish population. Many of them moved across Eight Mile Road from northwest Detroit to Southfield in the White flight era (Fine Reference Fine1997). Although six of ten Southfield residents are now African Americans, Blacks and Whites living there share the same neighborhoods since the neighborhood segregation score is a low 24.

Columns to the right in Table 1 report the average percentage of residents who are White in the neighborhood of the typical Black resident and the average percentage of residents who are Black in the neighborhood of the typical White. Overall, Whites in these suburbs lived in neighborhoods where 8% of their neighbors were African American but in a number of the larger suburbs there was a higher representation of Blacks. Warren, the largest city in Macomb County whose “blue-collar Democrats” propelled Ronald Reagan to the White House in 1980 (Greenberg Reference Greenberg1985), now has a population that is 21% African American. Current White residents of that suburb live in neighborhoods where one resident in six is African American.

The one-half million African American residents of Detroit city in 2019 lived in neighborhoods where there are few Whites; on average, 7% White. It is different in the suburbs. In most of the larger suburbs, Blacks live in neighborhoods where two-thirds or more of the neighbors are Whites. The moderate or low segregation scores may persist in many Detroit suburbs because African Americans migrating to the suburbs are almost as prosperous as Whites who live there. The final column to the right in Table 1, based on data from the 2015–2019 American Community Survey, shows the median income of Black households in a suburb as a percentage of the median income of White households living in the same suburb. In eight of the dozen suburbs, median Black household income was at least 83% that of Whites. In her essay “Home” in The House that Race Built, Toni Morrison (Reference Morrison and Lubiano1998) described her need to live in a race-specific home but also a nonracist home and the challenges that conundrum presents. Her observation is congruent with comments Detroit area Black respondents gave in our surveys; namely, they desired to live in an integrated neighborhood but a neighborhood where they will have Black neighbors. Recent suburbanization trends in metropolitan Detroit give African Americans the option to live in neighborhoods commensurate with economic status but with quite a few neighbors of both races. There are 864 census tracts in the suburban ring. In 2019, 51% of them had populations that were 6% Black or more. The in-migration of Blacks to Detroit suburbs is a boom for suburban real estate markets. The White suburban population is rapidly dwindling because of aging, but they are being replaced by younger, almost equally prosperous African Americans. In Warren, in 2019, the median age of Whites was forty-seven but only thirty for Blacks; in Clinton Township: forty-five for Whites but twenty-eight for Blacks.

SUBURBAN SCHOOLS: INTEGRATED OR SEGREGATED?

Much of the suburban ring is now residentially integrated. Does that mean that schools are also integrated? Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) was the most important Supreme Court decision about the nation’s Jim Crow school system. Arguably, the second most important decision involved Detroit and effectively slowed down the integration of schools. After Brown, the NAACP and African American activists in dozens of northern cities—including Ann Arbor, Jackson, Kalamazoo, and Lansing Michigan—filed suit charging that school districts unconstitutionally maintained segregated schools. Federal judges typically found for the plaintiffs and ordered integration, frequently by closing Jim Crow schools and busing students. Needless to say, parents and school officials were not pleased with these rulings. The district federal court mandated that children in the Pontiac district be bused beginning in the 1971–1972 school year (Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac 1970). On August 30, 1971, just before the opening of the school year, ten Pontiac school buses were blown up. Six members of the local Ku Klux Klan, including Michigan’s Grand Dragon, were arrested (Baugh Reference Baugh2011).

By the end of the 1960s, NAACP lawyers knew that, in many metropolises, White parents could avoid integration by moving from a central city to the suburbs. They sought a remedy and filed suit against the school system that served Charlotte, NC and its suburban ring. The litigation reached the Supreme Court and, in April 1971, a unanimous court ruled that a massive reorganization must be implemented quickly to end the racial segregation of schools in Charlotte and its suburbs. The court specifically mentioned busing, the need for immediate action, and legitimized the use of racial ratios to accomplish integration. Arguably, this was the most encompassing school integration ruling issued by the highest court (Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg 1971).

After schools in metropolitan Charlotte were integrated by busing, NAACP lawyers sought a ruling in the North where there was de facto but not de jure segregation. They chose metropolitan Detroit, perhaps because of the prosperity of the city’s African American residents. That is, Detroit Blacks in Census 1970 reported higher average family incomes than did the nation’s White families. District federal judge Stephen Roth heard the Detroit litigation. Presumably influenced by the unambiguous Swann ruling, Judge Roth concluded that changes were needed to fulfill the promise of Brown (Adams Reference Adamsforthcoming) The school age population of the city was overwhelmingly African American, while the suburban public schools overwhelmingly enrolled Whites. After consulting with experts and examining proposed remedies, Judge Roth ruled that city students should be bused to largely White suburban schools for eight of their twelve years of schooling, while suburban students would be bused to large city schools for four years. Vibrant opposition came from parents of both races and political officials. The Circuit Court of appeals approved Judge Roth’s plan, but the Supreme Court overturned it (Milliken v. Bradley 1974). There were eighty-six suburban school districts in the Detroit suburban ring at that time and fifty-four of them were involved in the proposed busing. The Supreme Court ruled that the plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate that the suburban districts were responsible for the segregation of White children from Black within the city of Detroit so the suburban districts could not be included in the remedy. In his dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall cogently predicted the future:

School district lines, however innocently drawn, will surely be perceived as fences to separate the races when, under a Detroit-only decree, White parents withdraw their children from the Detroit city schools and move to the suburbs in order to continue them in all-White schools

(Milliken v. Bradley 1974).The city’s schools quickly became almost exclusively African American (Bassett Reference Bassett and Tegeler2019; Baugh Reference Baugh2011). Brown marked one turning point in the efforts to integrate schools. Milliken v. Bradley marked another, since numerous subsequent Supreme Court decisions tampered efforts to integrate public schools in places including Charlotte (Walsh Reference Walsh2002), Louisville (Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education 2007), and Seattle (Parents Involved v. Seattle 2007). Milliken v. Bradley established the principle that if school segregation results because White and Black children live in different school districts, there is no constitutional mandate to integrate the schools.

Describing what happened to schools in recent decades in the Detroit area is complicated, but there are indications of substantial suburban school integration. There are now eighty-three suburban districts in the ring. For the most part, their boundaries do not correspond to municipal boundaries. There have been tremendous changes in school organization and funding since the Milliken decision. In 1994, state voters approved Proposal A. Traditionally, Michigan school districts were supported by local property taxes, but Proposal A ended that. State sales and tobacco taxes were raised, and a new tax was imposed on property sales in an effort to equalize school funding. The state now sends every public-school district $8,100 annually for each student enrolled (Summer Reference Summer2019). School districts may ask local property owners to tax themselves for capital improvements in the schools but there is a cap on that rate.

In 1994, Michigan adopted a freedom of choice enrollment policy. If a district were willing to enroll students from outside their catchment area, they could do so. They would get the state funded appropriation attached to each student. Most suburban districts now have great overcapacity because of their aging White populations and the persistent out-migration from Michigan. Many suburban districts, but not Grosse Pointe, not only welcome students from out of the district but actively recruit them. In the 2019 academic year, about 30,000 students residing in Detroit attended suburban schools while the city’s schools—public and charter —attracted about 5000 suburban students (Einhorn Reference Einhorn2018; Gerstein Reference Gerstein2019).

In 2011, Michigan’s legislature approved the nation’s most flexible law concerning charter schools. Entrepreneurs, non-profits, traditional public-school districts, and others—but not religious groups—can readily establish state funded charter schools with few regulations (Benelli Reference Benelli2017). The charter school receives $8,100 from the state for each student they enroll, money that would have gone to the public-school district where the student lived. Numerous charter schools were quickly established but quite a few did not survive for long. By 2019, there were seventy charter schools and fifty-one public schools operating in the city of Detroit. The charter schools enrolled about 51,000 Detroit youngsters and the public schools about 49,000 (Einhorn Reference Einhorn2018).

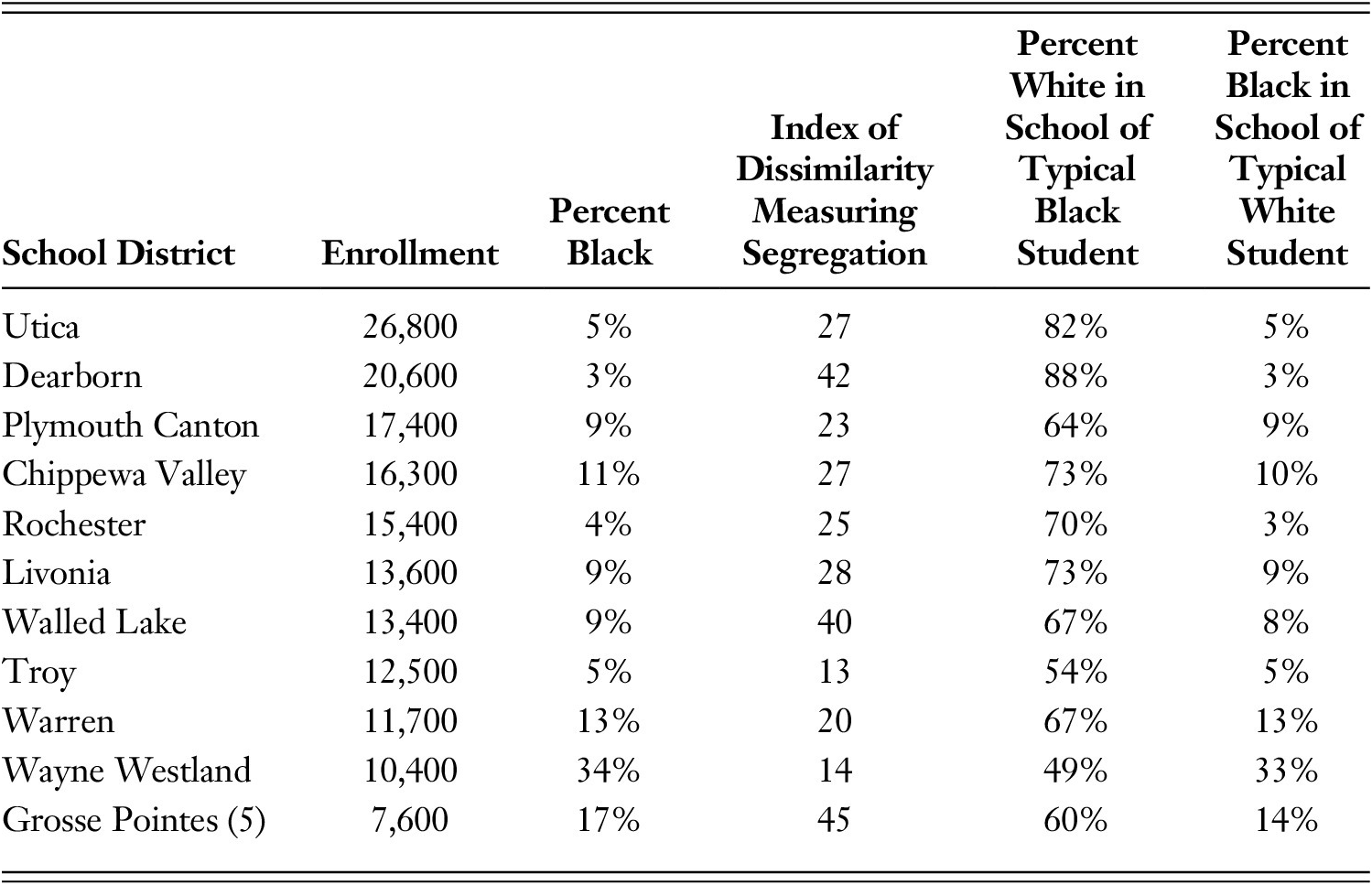

To determine whether suburban public schools were racially integrated, I considered the ten largest suburban school districts and the Grosse Pointe district with data for the 2019–2020 academic year. Data about these districts are shown in Table 2. Their enrollments range from a high of 28,000 students in the Utica district to 8000 in Grosse Pointe. The percentage of African American students ranged from 35% in Wayne-Westland to just 3% in Dearborn. In most of the districts, about one in ten of the students were African American. In the Detroit public school district, 82% of the students were African American (Michigan 2021a).

Table 2. Indicators of Racial Segregation in the Ten Largest Suburban Public-School Systems and the Grosse Pointes. Data for the 2019-2020 School Year

In this analysis, schools are the units used for calculating the index of dissimilarity. The indexes of racial segregation are low, suggesting that Blacks and Whites generally attend the same schools in these suburban districts. Dearborn and Grosse Pointe had scores of about 40, meaning that four in ten students in each district would have to change from one school to another to eliminate segregation. This is a moderate score. Other districts were even less segregated: 28 in Livonia; 20 in Warren Consolidated, and 14 in Wayne Westland. As the number in the right-hand columns reveal, both White and Black children in these districts attend schools that enroll considerable numbers of the other race. In 2019, 48%of the metropolitan area’s African American school age population of the metropolis lived in the ring. The Opportunity Atlas (2021) Project at Princeton classified neighborhoods with regard to whether or not their characteristics seemingly promote upward social mobility using modeling developed by Raj Chetty and colleagues (Reference Chetty, Hendren, Cline and Saez2014). The migration of African American children from Detroit to the ring is also a shift from living in census tracts linked to low rates of upward mobility to neighborhoods more favorable to mobility. The NAACP’s efforts in the 1970s to ensure that Black children attended integrated schools came to naught but the migration of African Americans from the city to the suburbs means that about one-half of the area’s Black students attend integrated schools.

Warren is an example of the racial change that occurred in the last half century. George Romney was Michigan’s governor when Detroit was riven by racial violence in 1967. He recognized that industrial cities such as Detroit and Flint were rapidly losing both employment and their financial base. He concluded that isolating White, Black, and Brown families in deteriorating cities was a recipe for revolution (Taylor Reference Taylor2019). President Nixon appointed Romney to head Housing and Urban Development. Once in office, Secretary Romney developed a “carrot and stick” approach. Suburbs that were particularly adamant about preserving race and class residential segregation were warned they could lose federal grants. Two suburbs—Warren, Michigan and Blackjack, Missouri—challenged Romney’s approach and sought to thwart his efforts to terminate federal funding in suburbs that excluded low-income people and minorities. Romney came to Warren to hold a public meeting to promote equal housing opportunities. Shortly after it began, his security detail had to whisk him out of the meeting and speed him away, lest he be physically attacked (Flint Reference Flint1970). Fifty years later, Warren is a prosperous suburb where one-fifth of the residents are African American and there is relatively little racial segregation in its neighborhoods or its schools.

ARE THERE PROSPECTS FOR REVITALIZATION AND RACIAL INTEGRATION IN THE CITY OF DETROIT?

In the sixty years following 1950, the city of Detroit lost 62% of its population and much of its tax base. The recession that began in 2008 accelerated that already sharp decline as employment fell, tax revenues disappeared, state revenue sharing was drastically cut, and the city approached insolvency. The governor appointed Kevyn Orr, an experienced bankruptcy attorney, as the Emergency Financial Manager who would administer the city’s finances. He quickly recognized that the city did not have the funds to pay its obligations and maintain services, so he recommended bankruptcy.

Detroit received approval from the state to enter bankruptcy in 2013. Federal bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes quickly found that the city had total debts approaching $17 billion and unsecured debts of $9 billion. Federal Judge Gerald Rosen was appointed to mediate the debt claims and, using the power of federal courts, most creditors settled for partial payment. In the 1920s, the prosperous city of Detroit erected the magnificent Detroit Institute of Art and dispatched the curator to Europe to purchase an extensive array of masterpieces. About one-half of the city’s unsecured debt involved obligations to retired city employees. Their spokespersons called for selling the Art Institute—the sixth largest in the nation— and its collection to fund pensions. The bankruptcy judge had the art assessed. Various estimates placed the value of the collection in the one to four-billion-dollar range. At this point, Judge Gerald Rosen worked out “The Grand Bargain.” The Ford, Kellogg, Kresge, Mott, and Skillman foundations agreed to put up $366 million, the State of Michigan $350 million and the Detroit Institute of Art agreed raise $100 million from its benefactors. The art gallery and its collection were transferred to a private non-profit and the $816 million funded the pensions. Retirees got a substantial fraction but certainly not all of what they were owed. The firms that insured the bonds of debtors negotiated at length but settled when they were given the option to purchase valuable city owned property near downtown and the waterfront. The city exited from bankruptcy in 2014 (Bomey Reference Bomey2016).

Developments in the ensuing years offer hope the city may be revitalized as a prosperous location offering employment and residential opportunities to a diverse population. Coming out of bankruptcy, the city needed capital to provide services that had been neglected for decades, needed an increase in jobs for its residents, and needed major investments to improve the quality of life. After bankruptcy, for the first time in decades, the city’s government gained access to funding that would support capital improvements and revitalization, which came from diverse sources. First, federal bankruptcy law assumes that municipalities will continue to operate after bankruptcy. Judge Steven Rosen made sure that the city would have approximately $1.5 billion in capital at the end of proceedings. Thus, the city had some discretionary capital to rebuild the city.

Michael Duggan, who was elected in 2013, became the first White man to serve in that office since 1973. The new mayor used those funds to strengthen the police department, to upgrade the city’s information technology and communication system, and to raze abandoned homes. When Duggan took office, fewer than half of the city’s streetlights worked but they were restored by 2015 (Kinzey Reference Kinzey2015). With assistance from the federal government, the mayor was able to improve bus service and later restored street cleaning in Detroit. Street cleaning and other city services, such as park maintenance, had been terminated in the lean years (Kinder Reference Kinder2016).

Second, largely because of the availability of funds from new sources, the city government developed and implemented programs to simultaneously upgrade the Woodward corridor, the downtown area, the Detroit River waterfront, and invest in neighborhoods. A light rail line was built along Woodward from the riverfront to the now booming New Center area. It was primarily financed by private firms and foundations. Within six years of announcing that project, about $13 billion was spent on new construction and the renovation of old office buildings, hotels, residences, and other structures within walking distance of the line. Mayor Duggan recruited an innovative city planner, Maurice Cox, who devoted himself to a Strategic Neighborhood Program. This involved identifying ten residential neighborhoods far from downtown where there were numerous abandoned homes but also many occupied ones and others that could be rehabbed. Using city funds and substantial investments from local banks, resources were devoted to these neighborhoods and to the financing of local businesses on nearby commercial streets. Numerous Detroit neighborhoods that were at risk of rapid decline during bankruptcy are on the road to stabilization after these investments.

Third, it is difficult to quantify but conflict between the city’s government and state government and between the city and suburban officials abated after the city’s bankruptcy. As major investments were made in the city, it becomes clear to Michigan and suburban residents that a prosperous Detroit is beneficial. The state funded its first urban park along the waterfront in downtown Detroit. During bankruptcy, the state leased Detroit’s Belle Isle park and invested more than $20 million in a renovation that produced, arguably, the most appealing urban park in the nation. In 2021, USA Today named the Detroit Waterfront as the most attractive in the country (Welch Reference Welch2021).

The state of Michigan twice took over the city’s schools because of the low-test scores of students and financial mismanagement. Alas, conditions did not improve with state management and city residents kept pushing for local control (Kang Reference Kang2020). Finally, in 2017, the state returned Detroit’s schools to local control. But when they administered them, the state had added about $500 million to the school district’s indebtedness. Rather than burdening city residents with that huge obligation, the state paid those debts when they created a new Detroit Public School District in 2017.

There is a long tradition of racial “dog whistling” by political candidates in the metropolis. City candidates assured their constituents that they would protect the city when prosperous suburbanites returned to take over the assets of Detroit. Suburban candidates emphasized the high crime rates in Detroit and their dedication to keeping “those people” out of the suburbs (Williams Reference Williams2014). This appears to have decreased after bankruptcy, perhaps because of the migration of African Americans to the suburbs and increasing diversity within the city. Mayor Duggan ran for reelection in 2017 against Coleman Young, II—son of the famous mayor. Duggan won with 72% of the vote (Stafford Reference Stafford2017).

Fourth, and extremely important for the revitalization of the city, large firms are now making multi-billion-dollar investments that will bring employment and neighborhood stabilization to Detroit. Thanks to the bailouts of the failing Chrysler and GM firms initiated by President Bush’s Administration and extended by President Obama (Murray and Schwartz, Reference Murray and Schwartz2019), Detroit remains axis mundi for the nation’s vehicle industry and is now becoming a major fiscal center, thanks to the presence of Ally Financial and Quicken Loans at Campus Martius. Quicken now employs 15,000 in the city (Crain’s Detroit Business 2021). Chemical Bank, formerly headquartered in New York, merged with TCF Financial and then Huntington to create one of the fifty largest banks in the country. In 2021, they completed construction of a new twenty-story headquarters building on Woodward Ave., meaning one of the nation’s largest banks is now headquartered in downtown Detroit (Reindl Reference Reindl2019). After setting up their headquarters in downtown Detroit in 2021, Huntington announced they allocated one billion dollars for loans to small businesses, underserved areas, and minorities in Detroit and Wayne County (Manes Reference Manes2021). Ford Motor Company, in 2018, purchased the long vacant but elegant Michigan Central Railroad Station, designed by the architects who designed Grand Central Station in New York. Ford and is now completing a $750 million investment to turn that building into a research center for the design of automated electric vehicles. This will bring at least 5000 new jobs to the city. Stellantis (nee Chrysler) is investing more than $3.3 billion in the renovation of their massive assembly plant on the east side of Detroit and the construction of a new assembly plant at the same location. In June 2021, Stellantis began assembling their new three bench Jeep Cherokee at new plant employing 4900 workers, 2100 of them city residents (Noble Reference Noble2021). This has already led to major investments by parts suppliers in new facilities in Detroit (Thibodeau Reference Thibodeau2019).

Importantly, the city of Detroit requires that when firms such as Ford and Stellantis obtain tax abatements as they typically do, they must sign Community Benefits Agreements. Ford and Stellantis have done so and upwards of $50 million will be available to establish training programs for new workers in their facilities, to strengthen local small businesses, and to provide loans to homeowners who live near the new or renovated plants. General Motors is investing more than $2 billion in the renovation of their huge assembly plant on the Detroit-Hamtramck border. It will be renamed Plant Zero since it will be the production center for GM’s electric trucks. Daimler continues to operate a large plant on the west side of Detroit assembling diesel motors for vehicles and Amazon is now constructing a major warehouse facility in northwest Detroit. The Detroit Medical Center and Henry Ford Hospital recently completed major expansions of their facilities. Medical sector jobs will increase as the state’s population rapidly ages. It is foreseeable that employment will increase in Detroit for both skilled blue-collar workers and professionals.

There was another source of capital for Detroit’s renewal: the deep pockets of philanthropic organizations that are linked to Detroit, including Ford, Kresge, Kellogg, Skillman, and Ralph C. Wilson. Traditionally foundations invested in art galleries, symphonies, and university buildings. As Detroit approached and then came out of bankruptcy, local foundations altered their spending and began devoting substantial funds to projects that would have been supported by tax dollars in a financially secure city. The Skillman Foundation devoted $100 million over ten years in six low-income and under-served Detroit neighborhoods to improve life outcomes for children and their families with an emphasis on educational attainment (Allen-Mears et al., Reference Allen-Meares, Shanks, Gant, Hollingsworth and Miller2017, Burns et al., Reference Burns, Brown, Colombo and O’Laoire2017). The Ralph C. Wilson Foundation, in 2018, announced plans to devote $100 million to improving parks in the city of Detroit, including the funding of an innovative riverfront park to be designed by the knighted architect David Adjaye. The Kresge Foundation funded about 20% of the cost of the Woodward streetcar line, appropriated $50 million for the renovation of Detroit’s waterfront, and recently announced major funding for a racial justice initiative in Detroit. In addition, the Kresge Foundation purchased the sylvan campus of the former Marygrove College in northwest Detroit and turned it over to the new Detroit school district. An innovative K–12 school is being created there in cooperation with the colleges of education at Michigan and Michigan State. The Erb Family Foundation and the John S. Knight Foundation support a variety of arts organizations in the city. The Kresge Foundation also provides funds for the Detroit Regional Partnership which seeks to promote economic opportunities for all in the area. The Ford Foundation now devotes about $13 million annually to support non-profits focused upon improving the quality of life in the city. The Davidson, Fisher, Hudson-Webber, Kellogg, Knight, Kresge, Mott, Skillman, and Wilson foundations collaborated to commit $159 million to create a New Economic Initiative for southeast Michigan. This organization emphasizes entrepreneurial activity, start-up financing for new businesses, and the training of workers for those firms.

In 2021, Dan Gilbert of Quicken Loans announced that his philanthropic organizations would spend $500 million over ten years for the redevelopment of Detroit neighborhoods (Pinho Reference Pinho2021). Importantly, $15 million was made available immediately to assist people who were in arrears on their property taxes; many of them in arrears because of the city’s failure to reassess. Foreclosures were postponed at the start of the pandemic but are to resume in 2021. The state of Michigan frees homeowners from paying property taxes if their income is below the federal poverty line, but it is a complicated and seldom used bureaucratic process. Presumably, the Gilbert funds will allow several thousand low-income Detroit residents to remain in the homes they own. Philanthropic support for infrastructure and for human capital development may increase if equity markets continue to prosper since federal law mandates that foundations spend about 5% of their endowments annually or pay substantial income taxes. The post-bankruptcy capital investments may explain why Fortune magazine published an essay entitled: “How Detroit Became a Model for Urban Renewal” (Scher Reference Scher2019).

The American Recovery Act, enacted in March 2021, is another source of funds for revitalizing the city and its public-school system. These monies were allocated to local governments on the basis of population size and need. The city of Detroit was earmarked to receive $880 million or about $1,300 per person (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2021). These American Recovery Act dollars are equivalent to about 42% of the city’s annual budget. Funds were allocated to public school districts on the basis of their enrollments and the economic status of children in the area they served. The public schools of Detroit are scheduled to receive $808 million from the American Recovery Act or about $16,500 per student. There is another substantial source of funding on the horizon for the city’s public schools. After years of mismanagement by the state, six students from Detroit public schools sued in federal court contending that the state ran the schools so incompetently that they had attended them for years but remained illiterate. They asserted that Michigan had a constitutional duty to provide schools that actually taught students to read and write. A judge on the Sixth Circuit Court of appeals ruled for the plaintiffs and concluded that the state had unconstitutionally “deprived them of access to literacy.” The state government opted for a settlement. Each of the plaintiffs obtained $40,000 and the governor promised to annually seek substantial funds to improve literacy in Detroit schools (Strauss Reference Strauss2020). Governor Whitmer is requesting $94 million in additional funds in 2021 which is about $1,300 per student (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2020).

Many of the most visible accomplishments in the renovation of Detroit are located downtown, along the Woodward corridor or near the spectacular riverfront. It is not rare to read comments asserting that the revitalization of Detroit will primarily or exclusively benefit wealthy investors, and the extremely skilled individuals who will come to Detroit to accept high paying jobs in technology and finance, while doing little to benefit those who have lived in Detroit’s low-income neighborhoods for decades (Williams Reference Williams2020; for an opposing view, see Dimon Reference Dimon2015). Before endorsing that pessimistic view, it is appropriate to observe that changes are occurring to improve the quality of life for all. Jobs at many skills levels are increasing, training programs have been initiated, property taxes (Berry Reference Berry2020) and car insurance rates have been reduced somewhat (Oosting and Wilkinson, Reference Oosting and Wilkinson2020), and a serious effort is underway to make the schools effective. Renewal efforts are underway in many of the city’s neighborhoods.

For the first time in many decades there are substantial investments being made throughout the city of Detroit. Does this mean that racial residential segregation will decrease? Detroit encompasses a large geographic area. You could fit Boston, Manhattan, and San Francisco within Detroit and have a great deal of land to spare. It is also a city of well over a hundred identifiable neighborhoods, each with a unique history. There is an untold story of residential integration in the city. In the late nineteenth century, when Detroit became the nation’s leading manufacturing center, and in the 1920s when the vehicle industry created great wealth, successful individuals commissioned famous architects to design mansions and magnificent homes. As a result, some of the most attractive neighborhoods in the nation’s older cities are found in Detroit. They account for a small share of the city but neighborhoods including Palmer Woods, Boston Edison, Indian Village, and Sherwood Forest have been integrated for twenty-five years or more (Rodwan Reference Rodwan2017). As Alan Mallach (Reference Mallach2018) argues convincingly, in the last three decades economic polarization has greatly increased in older cities and they are now populated by the rich and the poor while their economic middle class shrinks. Detroit illustrates his observation.

In numerous Detroit neighborhoods, substantial and architecturally appealing residences were constructed during the decades when the city boomed, often near the most elegant neighborhoods. These areas were once at risk of falling into decline but appear to be prospering in these years of revitalization. Data from recent Census Bureau surveys suggest they are attracting a diverse population. Indeed, there are more than a few people coming to Detroit with the aim of restoring a once glorious home to its original grandeur (Haimerl Reference Haimerl2016; Philips Reference Philip2017).

In downtown Detroit, in the New Center area, along the riverfront, and in the area within walking distance of the Michigan Central Station, there is now extensive construction of new residences and the conversion of classical older buildings into apartments and condos. This likely will be where many of the younger people coming to Detroit for jobs will reside, presumably a diverse population. Much of this new construction and renovation is eligible for benefits from the Low-Income Tax Credit program or the city’s community benefits requirement when tax abatements are involved. This means that a developer obtains a tax credit if a fraction of the new units are affordable by households with incomes below 60% of the area’s median income.

Private investors, speculators, and urban pioneers are active in the outlying neighborhoods of Detroit. Many of them are innovative. There is a dynamic urban farming movement in Detroit’s North End and other neighborhoods. In the Core City neighborhood, Los Angeles architect Philip Kafka created a residential-work community demonstrating that a modern version of Quonset huts provides attractive, moderate priced housing and workspaces (Runyan Reference Runyan2017). In several other neighborhoods, efforts are underway to demonstrate that shipping containers may be reconstructed and adapted for use as homes. And the tiny house movement has come to Detroit (Fowler Reference Fowler2018). Finally, the Warrendale and Bangla Village neighborhoods are being renewed by immigrants arriving from Bangladesh and Yemen.

Are these efforts having the desired consequences? It is too early to write a definitive report about whether the city of Detroit has turned a corner, but there are some positive indicators. According to the Census Bureau’s estimates, the city of Detroit lost 17,900 Black residents each year from 2000 to 2013 when the city entered bankruptcy. From 2013 to 2019, the annual loss declined to 5900, suggesting that African American out-migration to the suburbs slowed. From 2000 to 2013, the city lost an average of 3400 White residents each year. In the following six years, the city gained an annual average of 1400 White residents. Between 2000 and 2013, the number of Detroit residents who were employed fell by an average of 13,300 each year. From 2013 to 2019, that number increased by 8300 annually. From 2013 to 2019, per capita income, in constant dollars, rose 24% and median household income by 19%. Bankruptcy, perhaps, marked a turning point in Detroit’s demographic and economic trajectory.

CONCLUSION

In the mid-1970s, I collaborated with a team to conduct a survey in metropolitan Detroit about the reasons for the persistently extreme levels of racial residential segregation. Our study gave us little reason to hope for a reduction in the Jim Crow pattern. For years after that, surveys reported strong White opposition to government programs promoting residential integration (Schuman and Bobo, Reference Schuman and Bobo1988). To title our Detroit paper (Farley et al., Reference Farley, Schuman, Bianchi, Colasanto and Hatchett1978), we selected the title of a song that was then frequently played on soul music stations: “Chocolate City, Vanilla Suburbs” (1975)—a very apt description of metropolitan Detroit in that era. There is still substantial residential segregation in the metropolis but “Chocolate City, Vanilla Suburbs” is no longer an apt description.