Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial period for the development of emotional and social functioning (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Bittencourt-Hewitt and Sebastian2015; Blakemore, Reference Blakemore2008; Theurel & Gentaz, Reference Theurel and Gentaz2018) and a sensitive time for emergence of depressive and anxiety disorders in response to stressful events (Barrocas & Hankin, Reference Barrocas and Hankin2011; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Davis, Palma, Sandman and Glynn2022). Polish adolescents have experienced many stressors since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Firstly, they were faced with challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: long periods of remote learning, the need to adapt to ongoing changes, and interruption of daily routine, reduced opportunities for interactions with peers, the uncertainty about the course of the pandemic, and health concerns. After 2 years of dealing with these pandemic-related challenges, after February 24, 2022 the war in Ukraine, a country bordering Poland, introduced new stressors and concerns such as fear that the war will spread to Poland, distress associated with facing humanitarian crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and challenges associated with providing support for the influx of Ukrainian refugees in Poland (Brągiel & Gambin, Reference Brągiel and Gambin2023; Shevlin et al., Reference Shevlin, Hyland, Karatzias, Makhashvili, Javakhishvili and Roberts2022). Finally, both the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine contributed to a burgeoning financial, economic, and energy crisis in Poland which also raised concerns and fears for many individuals, including adolescents.

Adolescent’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have examined the mental health of children and adolescents from various countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies have consistently shown higher rates of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic estimates (Kauhanen et al., Reference Kauhanen, Wan Mohd Yunus, Lempinen, Peltonen, Gyllenberg, Mishina, Gilbert, Bastola, Brown and Sourander2023; Meherali et al, Reference Meherali, Punjani, Louie-Poon, Abdul Rahim, Das, Salam and Lassi2021; Panchal et al., Reference Panchal, Salazar de Pablo, Franco, Moreno, Parellada, Arango and Fusar-Poli2023; Racine et al., Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan2021; Samji et al., Reference Samji, Wu, Ladak, Vossen, Stewart and Dove2022). In addition, girls, older adolescents, and individuals with previous mental health difficulties, neurodiversities, and/or chronic physical conditions were characterized by higher severity of symptoms. Racine and collaborators (Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan2021) demonstrated that the pooled prevalence estimates of clinically elevated depression and anxiety were 25.2% and 20.5%, respectively, in their meta-analysis of studies of children and adolescents from East Asia, Europe, North America, Central America, South America, and Middle East.

Trajectories of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic in adolescents

It is now well-established that human responses to stressful life events typically evidence considerable heterogeneity (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini2011; Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004), and can be captured by a small number of prototypical trajectories. Resilience, characterized by a stable trajectory of mental health in the aftermath of a highly aversive or potentially traumatic life event, is the most common outcome trajectory and almost always observed in a majority of children, adolescents, and adults (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004, Lai et al., Reference Lai, La Greca, Brincks, Colgan, D’Amico, Lowe and Kelley2021). Other prototypical longitudinal outcome patterns include: chronically elevated distress; a recovery pattern – acute elevations in distress that gradually abate over time; and a delayed/worsening pattern – initially moderate or subclinical distress that worsens over time (for review, see Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018). These prototypical trajectories of mental health have also been observed among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Oleksy, Sękowski, Wnuk, Woźniak-Prus, Kmita, Holas, Pisula, Łojek, Hansen, Gorgol, Kubicka, Huflejt-Łukasik, Cudo, Łyś, Szczepaniak and Bonanno2022) and across the globe (for review, see Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Kunzler, Kalisch, Tüscher and Lieb2022).

While the increased severity of adolescent mental health problems during the pandemic has been widely documented (e.g. Kauhanen et al., Reference Kauhanen, Wan Mohd Yunus, Lempinen, Peltonen, Gyllenberg, Mishina, Gilbert, Bastola, Brown and Sourander2023; Meherali et al, Reference Meherali, Punjani, Louie-Poon, Abdul Rahim, Das, Salam and Lassi2021), to date, just a couple of studies have investigated longitudinal patterns of changes in mental health outcomes during the pandemic in youth – two such studies were conducted in China in the first months of the pandemic in 2020 (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Ross, Ma, Zhang, Fan and Liu2022a, Reference Wang, Zhao, Zhai, Chen, Liu and Fan2022b), and one was carried out in the Netherlands from February/March 2020 before the COVID-19 outbreak up to 15 months after the start of the pandemic (van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Creemers, Vogelaar, Saab, Miers, Westenberg and Asscher2022). Consistent with the previous trajectory research, the majority of the adolescents in these studies (55.8%–93.3%) responded with the resilient pattern of consistently low intensity of depressive/anxiety symptoms. In addition to the resilient group, Wang and colleagues (2022a) identified several other patterns for anxiety and depression, diverging slightly from the prototypical trajectories. These included chronic distress, recovery, worsening distress, and a relapsing/remitting trajectory. Furthermore, both Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhao, Ross, Ma, Zhang, Fan and Liu2022b) and van Loon et al. (Reference van Loon, Creemers, Vogelaar, Saab, Miers, Westenberg and Asscher2022) in addition to resilient groups, found chronic-like trajectories among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. These trajectories were marked by stable depression and anxiety levels, showing minor improvements (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Ross, Ma, Zhang, Fan and Liu2022b; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Creemers, Vogelaar, Saab, Miers, Westenberg and Asscher2022) or a moderate-stable pattern (van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Creemers, Vogelaar, Saab, Miers, Westenberg and Asscher2022). However, they did not identify worsening and recovering patterns. Further studies are needed to investigate patterns of changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents from various countries at different stages of the pandemic and other overlapping social crises. This research will help identify groups at risk of chronic or worsening mental health outcomes.

Role of family functioning in adaptation to social crises

Previous studies have highlighted poor social support and family functioning among the important predictors of non-resilient trajectories, as well as higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ayuso et al., Reference Ayuso, Requena, Jiménez-Rodriguez and Khamis2020; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Dumas and Forbes2020; Panchal et al., Reference Panchal, Salazar de Pablo, Franco, Moreno, Parellada, Arango and Fusar-Poli2023; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Hernandez and Sharp2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Ross, Ma, Zhang, Fan and Liu2022a, Reference Wang, Zhao, Zhai, Chen, Liu and Fan2022b; van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Creemers, Vogelaar, Saab, Miers, Westenberg and Asscher2022). Physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with spending more time with the closest family members and limited contacts with people outside one’s home. This situation could be especially stressful for adolescents who not only faced developmental challenges of increased separation, individuation, and consolidation of psychosocial identity, but also dealing with negative family relationships (Li et al., Reference Li, Beames, Newby, Maston, Christensen and Werner-Seidler2022; Martin-Storey et al., Reference Martin-Storey, Dirks, Holfeld, Dryburgh and Craig2021; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Hernandez and Sharp2021).

The time of the outbreak of war in Ukraine was also challenging for many Polish families who struggled with stressful war-related information and threats (Brągiel & Gambin, Reference Brągiel and Gambin2023). Many of these families were also involved in providing various forms of support to Ukrainian refugees. This engagement could have affected family dynamics, potentially contributing to the exacerbation or persistence of depression and anxiety symptoms.

It is reasonable to argue that times characterized by social crises may be particularly difficult for youth who experience high levels of filial responsibility which refers to children’s instrumental and emotional caregiving behaviors within a family system (Barnett & Parker, Reference Barnett and Parker1998; Boszormenyi-Nagy & Sparks, Reference Boszormenyi-Nagy and Sparks1973). During periods of heightened stress and emotional distress experienced by family members, as well as difficulties in balancing work and family duties by parents, some adolescents may face greater expectations to meet the needs of their family members. They may also take on “adult roles” in the family by getting involved in instrumental and emotional caregiving.

Jurkovic and colleagues (Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005), following previous research and theoretical assumptions (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Krasner, Reference Boszormenyi-Nagy and Krasner1986; Jurkovic, Reference Jurkovic1997), proposed that perceived “familial fairness” plays a crucial role in determining if high levels of caregiving duties taken by an adolescent will be associated with positive or adverse psychological outcomes. Family fairness relates to: (i) a sense that adolescent’s caregiving is acknowledged, reciprocated, supported, and shared by family members; (ii) the family environment is supportive, validating, and responsive; and (iii) the balance of giving and taking in the family is fair (Jurkovic et al., Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005; Kuperminc et al., Reference Kuperminc, Jurkovic and Casey2009). Previous research confirmed that perceived familial unfairness is associated with adverse outcomes, in particular with higher levels of emotional distress (e.g. Cho & Lee, Reference Cho and Lee2019; Jankowski et al, Reference Jankowski, Hooper, Sandage and Hannah2013; Jurkovic et al., Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005). Additionally, it is suggested that a sense of familial unfairness gains more importance during stressful times and in the face of social injustice which may contribute to familial injustice (Jurkovic et al., Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005). Thus, it seems that experiences of both the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in neighboring Ukraine could be associated with risk of increased stress in the families, challenges for parents in balancing work and family duties, and lower responsivity toward the needs of their adolescent children. These changes in turn may result in adolescents’ experiencing lower levels of support, reciprocity, and equity in the family system that could contribute to development and maintenance of depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Current study

In the current study, we tracked trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms among Polish adolescents during the second year of the pandemic and after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, specifically between November 2021 and May 2022. We expected to find evidence of the four prototypical trajectories (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini2011; Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2004) observed in previous studies: resilient, recovering/improving, chronic, and worsening. However, because the stress of this period would likely be heightened due to the outbreak of war in neighboring Ukraine, we anticipated that the frequencies of the trajectories might vary relative to previous studies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the recovering group would likely be smaller, while the worsening or chronic groups, particularly for anxiety symptoms, would likely be larger due to the sustained uncertainty and threats posed by the overlapping social crises. We also examined likely risk/protective factors (predictors from the first wave of our study) of the trajectories related to family functioning, COVID-19 pandemic difficulties and threats, as well demographic variables.

Additionally, we anticipated that various longitudinal patterns of depressive and anxiety symptoms could contribute to emotional reactions and affect adaptation to new stressors experienced later in life. Individuals experiencing chronically elevated levels of emotional distress (anxiety and depression) could be more vulnerable to react with greater concerns to new life events in comparison to individuals experiencing resilient, stable trajectories of emotional functioning (Daley et al., Reference Daley, Hammen, Burge, Davila, Paley, Lindberg and Herzberg1997; Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Bäckström and Johanson2008; Mandavia & Bonanno, Reference Mandavia and Bonanno2019; Morin et al., Reference Morin, Galatzer-Levy, Maccallum and Bonanno2017; Silver et al., Reference Silver, Holman, McIntosh, Poulin and Gil-Rivas2002). Thus, in our study we investigated associations between longitudinal trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms and concerns related to the war in Ukraine experienced by adolescents in the third wave of our study.

Situation in Poland during data collection

First wave (8–17 November 2021)

In September 2021, Polish adolescents returned to in-person education after an extended period of continuous remote learning. The shift to online education was a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, introduced in March 2020, mirroring measures taken in many countries worldwide (Schleicher, Reference Schleicher2020; UNICEF, 2021). However, unlike numerous other countries (e.g. France, Belgium) where remote learning was implemented for relatively short durations (Schleicher, Reference Schleicher2020; UNICEF, 2021), Polish adolescents experienced a significantly longer period of online education. Polish youth participated in remote learning between March 2020 and September 2021, with only one break between 1st September and 24th of October 2020 and breaks for summer and winter holidays. At the time of the first wave of our study in November 2021 adolescents took part in in-person education, however due to an increase in the number of COVID-19 infections in Poland, there was uncertainty concerning the potential return to remote learning. Due to many outbreaks of infections in schools, several classes had to temporarily switch to remote learning. Students were required to wear masks during lessons and breaks, unless the principal decided otherwise. However, such decisions were rare in Polish schools. People were also required to wear masks and keep 0.5 m of distance from other people in public places. Some restrictions were still in place in cultural institutions.

Second wave (2–13 February 2022)

Students returned to school (in-person education) after winter break in the middle of January 2022. However, the government decided to implement remote learning again at the end of January because of the new variant of COVID-19 (Omicron) and the increase in infection numbers. Poles were also informed that the virus became more benign and thus the time of quarantine was reduced from 14 to 7 days. However, there were many restrictions at this time in Poland, i.e., only 30% occupancy was allowed in cultural institutions, restaurants, and churches. Hotels and clubs were closed. COVID-19 tests were obligated to roommates of individuals infected with COVID-19. At this time, there was also speculation in the press and media about a potential Russian attack on Ukraine and information about Ukraine’s preparations for defensive measures.

Third wave (18–30 May 2022)

At this time COVID-19 cases decreased and many restrictions were lifted. Adolescents went back to school (in-person education) at the end of February 2022 and they did not have to wear masks. The government reduced restrictions in shops and restaurants, and clubs were opened. The outbreak of war in Ukraine took place on February 24, 2022 followed by a refugee influx. In the period of 2 months between the outbreak of war and the end of May 2022 over 3 million Ukrainian refugees crossed the border into Poland. At the end of May 1.2–1.5 million Ukrainian refugees stayed in Poland. Poles were actively engaged in supporting the refugees in various ways. Information about the war, including war crimes committed by Russia in Ukraine, constantly appeared in the Polish media.

Method

Participants

The sample of the first wave included 281 participants (60.1% females and 38.4% males, 1.4% indicated other gender identity), in the age range from 16 to 18 years (age in months: M = 208.56, SD = 10.72) that were followed-up for approximately 7 months: Wave 2 (N = 188), Wave 3 (N = 164). The detailed description of the participants in three waves is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the participants in three waves

Measures

Based on the research mentioned above, we included sociodemographic, pandemic-related, and relational factors from the first wave of the study. These factors are potentially involved in the process of adaptation to the pandemic’s challenges and hardships. They include gender, age, parent’s education level, family structure, financial situation, pandemic-related difficulties, perceived COVID-19 risk, and familial unfairness, all of which we explored as possible predictors of depressive and anxiety trajectories.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) is a nine-item self-report tool for measuring the occurrence of depressive symptoms in the last 2 weeks. The participants give answers on a scale from 0 – not at all to 3 – nearly every day (sample item: Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties (e.g. Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Levis et al., Reference Levis, Benedetti and Thombs2019). A Polish translation was developed by the MAPI Research Institute (www.phqscreeners.com). The Cronbach’s alpha was α = .95 in our study.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) is a self-report measure for investigating the risk of generalized anxiety disorder. The scale consists of seven items about the frequency of symptoms during the last 2 weeks. Participants give answers on a scale from 0 – not at all to 3 – nearly every day (sample item: Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties (e.g. Rutter & Brown, Reference Rutter and Brown2017; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). A Polish translation was developed also by the MAPI Research Institute (www.phqscreeners.com). The Cronbach’s alpha was α = .96 in our study.

Filial Responsibility Scale for Youth (Jurkovic et al., Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005; Kuperminc et al., Reference Kuperminc, Jurkovic and Casey2009) is a self-report questionnaire that consists of 34 items and three subscales: instrumental caregiving, emotional caregiving, and unfairness. Participants responded on a Likert scale from 1 – not at all true to 4 – very true. The scale was translated into Polish using the back-translation method. Two of the items related to language brokering, that were used to study experiences of children from immigrant families, were not included in this study. In our statistical analysis we have included the unfairness subscale consisting of 11 items related to the perceptions of fairness, including equity and reciprocity (e.g., In my family, I am often asked to do more than my share). The unfairness subscale was characterized by very good reliability in both our study (α = .92) and previous research (e.g. Żarczyńska-Hyla et al., Reference Żarczyńska-Hyla, Zdaniuk, Piechnik-Borusowska and Kromolicka2019; Kuperminc et al., Reference Kuperminc, Jurkovic and Casey2009).

Scale of Pandemic-Related Difficulties for Adolescents. The scale was based on the Scale of Pandemic-Related Difficulties for Adults (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Sękowski, Woźniak-Prus, Wnuk, Oleksy, Cudo, Hansen, Huflejt-Łukasik, Kubicka, Łyś, Gorgol, Holas, Kmita, Łojek and Maison2021b) and adjusted to the situation of adolescents during the pandemic. Participants were asked 16 questions about possible difficulties during the pandemic. They were asked to “indicate to what extent each of the following was a problem for them during the last six months of the pandemic” and answered on a scale from 1 – it was not a problem at all to 5 – it was definitely a problem for me. Based on an exploratory factor analysis (for details and wording of all items see Supplementary Material 1, Tables S1 and S2), we created three subscales: household and school relationship difficulties that covers being overloaded by everyday duties, problematic relationships at home and at school, and difficulties in coming back to in-person education (4 items, α = .73, sample item: Difficult relationships with loved ones at home (feeling that we are getting on each other’s nerves); difficulties related to limited social connections, extracurricular and recreational activities due to COVID-19 restrictions (6 items, α = .84, sample item: Limited or no real meetings with friends/acquaintances/loved ones); and fear and uncertainty related to pandemic course and the COVID-19 infection (3 items, α = .79, sample item: Fear of infection of a family member /other close person with coronavirus).

Questions assessing war-related concerns . For the purposes of our study, we created four questions assessing war-related concerns. Participants were asked to indicate whether and to what extent they feel the following fears and anxieties related to the war in Ukraine: (i) concern about the spread of the war conflict on the territory of Poland, (ii) concern about economic difficulties caused by the war in Ukraine, (iii) concern about the challenges related to the presence of a large number of refugees from Ukraine in Poland, and (iv) anxiety and sadness at witnessing the suffering of people from Ukraine caused by the war. Adolescents answered on a Likert scale from 1 – I have no such concerns at all to 5 – I definitely experience such concerns.

Procedure

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw. The study was conducted on the Ariadna online research panel. Participants got points for filling in surveys on the research panel, which they can exchange for gifts. The studies were executed in three waves: (i) first wave between 8 and 17 November 2021, (ii) second wave between 2 and 13 February 2022, and (iii) third wave between 18 and 30 May 2022.

Analytical strategy

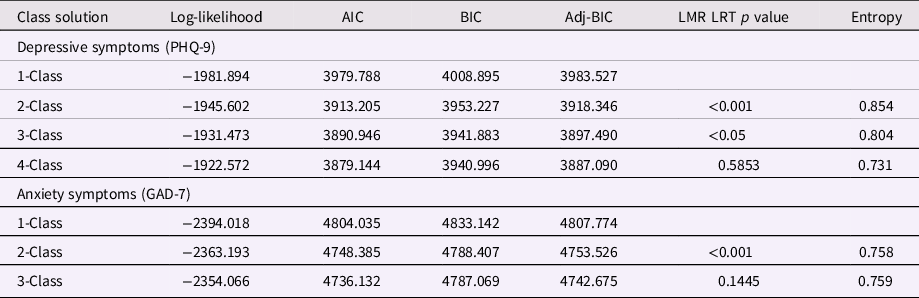

Analyses were conducted in Mplus (version 7; Muthén & Muthén, 2017) and R package (Rossell, Reference Rosseel2012). We used the maximum likelihood procedure (FIML) to impute missing values and MLR to account for non-normally distributed data. We employed a two-step approach. First, we identified the best fitting GMM for depressive and anxiety symptoms (without any predictors and distal outcomes). We ran models with an increasing number of trajectories until non-convergence was reached or sample sizes (proportion) per trajectory were below 5%. The relative fit of the GMM models was compared using the following criteria: the Akaike information criterion, the Bayesian information criterion, and entropy. Finally, we used the Lo–Mendell–Rubin (LMR) Likelihood test (see Jung & Wickrama, Reference Jung and Wickrama2008; Nylund et al., Reference Nylund, Asparouhov and Muthén2007 for a discussion on fit indices) to compare models with increasing numbers of trajectories. A nonsignificant value (p > .05) of the LMR LRT test means that the model with one fewer class is better. When negative residual variances appeared, the variances of the item were constrained to zero. Next, we used (multinomial) logistic regression to examine T1 predictors of membership in each latent class vs. the other classes, and to examine the relationship of those identified classes to war-related concerns (T3 distal outcomes). We refer to “distal outcome”– an observed variable that is treated as a dependent variable in the analysis in which the latent categorical variable is treated as a predictor.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

We compared two- to three-class models and based on the fit indices we chose a two-class model as the optimal solution for anxiety symptoms and a three-class model for depressive symptoms (see Table 2). For anxiety symptoms, we identified a resilient trajectory characterized by low, stable symptoms in 75% of participants, and a chronic group with consistently elevated symptoms in 25% of participants. In terms of depressive symptoms, we identified a resilient trajectory (accounting for 71% of participants) demonstrating stable mental health, a chronic group with elevated symptoms (11%), and a recovering group (18%) that showed acute symptoms followed by a decrease in depressive symptoms over subsequent waves, even after the onset of the war in Ukraine (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2. Model fit statistics for GMMs of depressive and anxiety symptoms

LMR LRT = Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood test.

Figure 1. Depressive symptoms trajectories.

Figure 2. Anxiety symptoms trajectories.

The depression and anxiety trajectory solutions were asymmetrical, i.e., had different numbers of classes, and thus could not overlap perfectly. Nonetheless, a comparison of trajectory membership (using Chi-square test and analyzing adjusted standardized residuals) showed a significant overlap between resilient trajectories for depressive and anxiety symptoms, between chronic anxiety and chronic depressive trajectories, as well as between chronic anxiety and recovering depressive trajectories (χ2(2) = 95.30, p < .001). Specifically, individuals within the resilient trajectory for anxiety symptoms were more likely to also be in the resilient trajectory for depressive symptoms (89.7% of participants) and less likely to be in non-resilient trajectories for depressive symptoms. Similarly, those within the chronic depressive trajectory and recovering depressive trajectory were more likely to be in the chronic anxiety trajectory (91% and 51% respectively) and less likely to be in the resilient trajectory (9.1% and 49% respectively) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Overview of class membership

The results of logistic regression analysis, examining T1 predictors of membership in each latent class vs. the other classes, revealed that individuals in the chronic anxiety group compared to the resilient group were significantly older, and reported a more detrimental financial situation. They also displayed higher levels of perceived unfairness than individuals in the resilient group. Additionally, father’s primary/vocational education compared to higher and secondary education was significantly related to membership in the chronic group (see Table 4).

Table 4. Predictors of anxiety trajectories

***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.

In the case of depressive symptom trajectories, individuals in chronic and recovering groups reported higher levels of perceived household, school and emotional difficulties, and greater perceived sense of unfairness compared to the resilient group. Other predictors were nonsignificant (see Table 5).

Table 5. Predictors of depression trajectories

***p < 0.001. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.

The results of GMM analysis with distal outcomes revealed significant differences among anxiety trajectory groups with higher concerns about economic difficulties caused by the war in Ukraine in the chronic group vs resilient group. Differences in other war-related concerns were nonsignificant (see Table 6). Membership in the chronic trajectory of depressive symptoms, compared to membership in the resilient group, was associated with higher concerns about the challenges related to the presence of a large number of refugees from Ukraine in Poland. Differences in other distal outcomes were insignificant (see Tables 7 and 8).

Table 6. Distal outcomes of anxiety trajectories (chi2 differences; means and standard errors)

Table 7. Distal outcomes of depression trajectories - chi2 differences

Table 8. Distal outcomes of depression trajectories – means and standard errors

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents during the times of overlapping crises – the COVID-19 pandemic and war-related social crises. We identified three depressive symptom trajectories: resilient (71%), chronic (11%), and recovering (18%). We also found two anxiety symptom trajectories: resilient (75%) and chronic (25%). There was a significant overlap between the trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Individuals within the resilient trajectory for anxiety symptoms were more likely to also be in the resilient trajectory for depressive symptoms. Similarly, those within the chronic anxiety trajectory were more likely to belong to the non-resilient trajectories for depressive symptoms.

Most of the chronic depressive individuals and over half of the depressive-recovering participants also experienced chronic anxiety. The strongest predictor of membership to all non-resilient trajectories (both chronic and recovery trajectories) was perceived unfairness. Adolescents in the non-resilient trajectories of depression reported higher levels of relationship difficulties at school and at home compared to the resilient group. In addition, older age, and poor socioeconomic status were predictors of chronic-anxiety trajectory. Finally, chronic trajectories of depressive and anxiety symptoms were positively associated with some of the war-related concerns.

Consistent with previous research on emotional responses to stressful and potentially traumatic events (Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018) the majority of participants were in the resilient trajectory with stable, low symptom levels for both depression (71%) and anxiety (75%) throughout the period considered. It seems that in this community sample, the majority of adolescents have found enough protective resources and promotive factors to successfully adapt to various challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent social crises (war in Ukraine, financial crises).

Interestingly, our study revealed somewhat different frequencies and patterns of trajectories relative to the prototypical trajectories (e.g. Galatzer-Levy et al., Reference Galatzer-Levy, Huang and Bonanno2018) and to our previous trajectory findings on adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Oleksy, Sękowski, Wnuk, Woźniak-Prus, Kmita, Holas, Pisula, Łojek, Hansen, Gorgol, Kubicka, Huflejt-Łukasik, Cudo, Łyś, Szczepaniak and Bonanno2022). We did not identify trajectories characterized by gradual worsening of depressive and anxiety symptoms over time, despite the fact that the war in Ukraine (a new crisis overlapping with the pandemic) started between the second and third waves of our study. In contrast to the study of Polish adults, which took place during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Oleksy, Sękowski, Wnuk, Woźniak-Prus, Kmita, Holas, Pisula, Łojek, Hansen, Gorgol, Kubicka, Huflejt-Łukasik, Cudo, Łyś, Szczepaniak and Bonanno2022), the current study was conducted during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. It took place over a long period (one and a half years) in which adolescents faced pandemic-related hardships and challenges. Since we did not measure the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms before the pandemic and throughout the initial one and a half years of the pandemic in the current study we cannot know how depressive and anxiety symptoms changed in youth at the earlier stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. It could be that some adolescents experienced a gradual worsening of symptoms during the initial months of the pandemic, but then found ways to adapt to social crises, resulting in either the absence of further deterioration in their mental health or a potential recovery.

Adolescents from the depressive-recovering group experienced a gradual decrease in depressive symptoms between November 2021 and May 2022. During this period, they primarily took part in in-person learning. However, prior to that, they endured a lengthy period of over a year dealing with remote education and other pandemic-related stressors. They may have also faced challenges in readjusting to the return to in-person education in September 2021. The improved mood in the recovering trajectory may have resulted from a decrease of pandemic-related stressors, return to in-person learning, increased social connections, and regular-daily routines. The recovering group did not display increased levels of war-related concerns, similar to the resilient group, which may have contributed to the reduced depressive symptoms this group experienced by the third wave. In addition, about half of participants in the depressive-recovering group experienced chronic anxiety symptoms and nearly all of the individuals in the chronic depressive group were also members of chronic-anxiety trajectory. In effect, the group of adolescents characterized by chronic anxiety symptoms was larger than the group displaying chronic depressive symptoms in our study. These findings suggest that the pandemic and war in the neighboring country, along with their perceived consequences, might have predominantly triggered and sustained either anxiety combined with depressive symptoms or only anxiety symptoms in Polish vulnerable adolescents. Depressive symptoms alone, not combined with anxiety, seem to be less prevalent in this context. The unique stressors arising from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine seem to differentially impact depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Depressive symptoms could be more prevalent at the time of heightened restrictions, remote learning, and limited social interactions that preceded our study. In contrast, chronic anxiety symptoms seem to be more prevalent at the time of our study due to the ongoing uncertainty, unpredictability, and potential threats related to the pandemic and the war.

It is possible that various war-related concerns could be in mutual relationship with chronic anxiety and depressive symptoms and lead to maintenance of high levels of emotional distress in Polish adolescents. In the context of the war in Ukraine, symptoms of anxiety could contribute to experiencing concerns about anticipated financial and life difficulties arising from the war. Meanwhile, symptoms of depression in Polish youth contributed to experiencing concern about the actual situation of the growing number of refugees from Ukraine and the demands and responsibilities associated with their stay in Poland. These war-related concerns and internalizing symptoms may perpetuate each other in a vicious cycle.

Perceived unfairness, which refers to the subjective sense of adolescents that their caregiving in the family is not acknowledged and reciprocated and that the family members are not supportive and responsive, was the strongest predictor of membership to all non-resilient trajectories (both chronic and recovery trajectories). Our findings are consistent with previous research indicating associations between perceived unfairness and negative mental health outcomes in adolescents and adults (Jankowski et al., Reference Jankowski, Hooper, Sandage and Hannah2013; Jurkovic et al., Reference Jurkovic, Kuperminc, Sarac and Weisshaar2005). It seems that a sense of unfairness could play a particularly important role in the emotional well-being of adolescents, including times of the COVID-19 pandemic and other social crises when whole families were struggling with many stressors and challenges. It is plausible that especially in times of social crises, adolescents could be objectively burdened with many “adult” responsibilities exceeding their normative developmental capacities. Moreover, some of them could also experience difficulties in acknowledging and understanding the struggles of their parents during the pandemic and time of outbreak of war in Ukraine who could be less available and responsive to their children’s needs due to their own emotional distress, as well as difficulties in balancing work and family duties. For non-resilient adolescents dealing with the combination of various challenges associated with both social and normative developmental crises (building autonomy, independence, self-identity, setting personal goals, and making plans for the future) could be too overwhelming and exceed their resources and coping abilities.

Finally, out of all pandemic-related difficulties at baseline, only household and school relationship difficulties were found to be significant predictors of non-resilient trajectories of depressive symptoms. Difficulties with relations with family members, teachers, and return to in-person education turned out to be more important predictors of elevated levels of depressive symptoms than concerns directly related to the pandemic (COVID-19 threat, uncertainty concerning the course of the pandemic or difficulties related to limited social connections, extracurricular and recreational activities due to COVID-19 restrictions). Consistent with cross-sectional findings of the effects of COVID-19 (Cortés-García et al., Reference Cortés-García, Hernández Ortiz, Asim, Sales, Villareal, Penner and Sharp2021; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Hernandez and Sharp2021), it seems that negative relational experiences could have more adverse effects on youth than limited relationships. Similarly, household relationship difficulties were a stronger predictor than other pandemic-related difficulties of depression and anxiety in various age groups of Polish adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Sękowski, Woźniak-Prus, Wnuk, Oleksy, Cudo, Hansen, Huflejt-Łukasik, Kubicka, Łyś, Gorgol, Holas, Kmita, Łojek and Maison2021b). Positive relationships within the family and school systems are crucial resources for promoting adaptation and positive emotional functioning among children and adolescents, especially during times of transition and change (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has presented unique challenges for young people who may already be struggling with negative family relationships. As lockdowns and social distancing measures were enforced, these adolescents had to spend more time at home, often in difficult relational contexts, and had limited access to social support from sources outside the family (Li et al., Reference Li, Beames, Newby, Maston, Christensen and Werner-Seidler2022; Martin-Storey et al., Reference Martin-Storey, Dirks, Holfeld, Dryburgh and Craig2021). For those who also experienced negative relationships with teachers, the readjustment to in-person education and the stressful school environment posed additional challenges.

Adolescents’ father’s lower level of education (vocational and primary education in contrast to secondary and higher education) was associated with membership to a chronic trajectory for anxiety symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that father’s level of education is positively associated with positive and emotionally supportive relationships with their children and partners, as well as with various positive child outcomes (better cognitive, relational, and emotional functioning) (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Woźniak-Prus, Konecka and Sharp2021a; Tamis-Lemonda et al., Reference Tamis‐LeMonda, Shannon, Cabrera and Lamb2004; Teufl et al., Reference Teufl, Deichmann, Supper and Ahnert2020). Therefore, a father’s higher education may provide various resources, such as positive parent–child relationships and better opportunities for child development, potentially protecting from uncertainty and anxiety stemming from late adolescence and social crises. Furthermore, a more detrimental financial situation was related to membership of a chronic trajectory of anxiety symptoms which is in line with our previous pandemic-trajectory study conducted in Polish adults (Gambin et al., Reference Gambin, Oleksy, Sękowski, Wnuk, Woźniak-Prus, Kmita, Holas, Pisula, Łojek, Hansen, Gorgol, Kubicka, Huflejt-Łukasik, Cudo, Łyś, Szczepaniak and Bonanno2022). Greater financial strain limits the possibility to access various resources, including access to private health care, educational, and recreational services, and contributes to elevated stress, especially during times of financial and economic crisis. Finally, older age was also related to membership to the chronic trajectory of anxiety symptoms in our study. Older age in adolescents could be associated with greater awareness of social crises (energetic, financial, and war-related crises) and fear of an uncertain future as well as greater pressure and uncertainty associated with entering adulthood roles.

There are several limitations of the current study. The study included only individuals who were members of the online panel. Thus, it limits the generalization of our findings to other populations. Moreover, variables included in the study were measured only with self-report scales that are subjective and vulnerable to biases (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). Finally, our study did not include the measurement of depressive/anxiety symptoms at the time points at the beginning of the pandemic and before the pandemic. Since prospective studies conducted prior to the pandemic identified a trajectory characterized by chronically elevated symptoms beginning well before the stressful event and continuing after the event (Bonanno et al., Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini2011), it is difficult to assess what part of Polish adolescents from chronic groups experienced higher levels of symptoms before the pandemic, and how large a percentage of them developed higher levels of symptoms during the pandemic or war in Ukraine.

On the basis of our results, and consistent with other studies (Cortés-García et al., Reference Cortés-García, Hernández Ortiz, Asim, Sales, Villareal, Penner and Sharp2021; Penner et al., Reference Penner, Hernandez and Sharp2021) we conclude that interventions focused on family relationships especially resolving subjective and/or objective familial unfairness in adolescents could be helpful in increasing resilience and preventing potential negative long-term outcomes of the stressful events as pandemic and other social crises. It seems that perceived unfairness could be resolved through different interventions by building communication, responsiveness of family members (during family therapy, parent training, adolescents or parents individual therapy) (Jankowski et al., Reference Jankowski, Hooper, Sandage and Hannah2013), as well as by supporting families and adolescents in overcoming challenges during the current social crises. It is plausible that various positive relational experiences (not only provided by the family but also by school and community networks) could be beneficial in decreasing adolescents’ perceived relational injustice, however further research is needed on this topic. Our study indicates the great need for investigating the effectiveness of preventive and therapeutic interventions aimed at increasing a sense of fairness in the family, which seems to be a robust factor protecting against the negative psychological effects of overlapping health, economic, and social crises. Further research should explore the role of various other vulnerability, risk, and protective or promotive factors (such as emotion regulation and mentalizing abilities, quality of attachment relationships, and social support) that could play a role in adolescents’ adjustment to these crises.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942300130X.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the adolescents who participated in the study.

Funding statement

The research and the publication is financed by the funds from the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw awarded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the form of a subvention for maintaining and developing research potential in 2021 and 2022.

Competing interests

None.