Policy Significance Statement

This study equips policymakers and industry leaders with evidence-based insights into the narratives that shape public perceptions of quantum technologies. An analysis of 2200+ documents reveals that while technical narratives dominate, geopolitical concerns are gaining ground, often at the expense of ethical considerations, especially in business and policy discourse. Unlike polarized debates on AI, quantum discourse remains cautiously optimistic but risks fostering innovation silos via “quantum race” framing. Our findings inform policy by (1) identifying governance gaps in current national quantum strategies, (2) demonstrating the need for inclusive innovation frameworks that address accessibility and equality, and (3) providing a replicable methodology for monitoring technology narratives across domains.

1. Introduction

Scientific advances in quantum physics and information theory have become the foundation for a range of emerging innovations collectively called quantum technologies (QTs). These generally fall into three categories: (1) quantum sensors capable of achieving extremely high measurement accuracy and precision of properties like time, gravity, or electric fields; (2) quantum communication systems capable of creating highly secure digital communication channels; and (3) quantum computers capable of solving computational problems beyond the capabilities of classical computers, including modeling chemical or physical systems at the subatomic level. The quantum mechanical phenomena of uncertainty, superposition, and entanglement (Hoofnagle and Garfinkel, Reference Hoofnagle and Garfinkel2022, p. 25) make these technologies possible.

QTs have the potential to outperform classical devices or create entirely new technological capabilities. For instance, quantum sensors could be used in medicine to improve precision in medical imaging and laser surgery (Kop et al., Reference Kop, Slijpen, Liu, Lee, Albrecht and Cohen2024) or in aerospace industries to enhance the detection sensitivity of radars (Mand and Uhlmann, Reference Mand and Uhlmann2020). Quantum communication offers fundamentally more secure methods to prevent eavesdropping and protect data transmission compared to existing cryptographic protocols (Travagnin and Lewis, Reference Travagnin and Lewis2019). Similarly, quantum computing shows promise in simulating complex systems, such as designing advanced batteries for efficient energy storage in material sciences (Quach et al., Reference Quach, Cerullo and Virgili2023) or tackling optimization challenges in climate modeling (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Di Paolo, Forrest, Hadfield, Sawaya, Stęchły and Thibault2021).

The above examples hint at the broad applicability of QTs to address key issues in information security, healthcare, and climate change, among others. However, it is unclear when (or if) these advantages are going to fully materialize because the technological readiness of QTs varies (de Jong, Reference de Jong2025). Quantum sensing technologies are comparatively mature; they have clear near-term use cases and are less complex than quantum computers (Hoofnagle and Garfinkel, Reference Hoofnagle and Garfinkel2022). Quantum communication technologies, such as quantum key distribution, are already being deployed, though large-scale quantum networks, like a quantum internet, remain a more distant goal (Travagnin and Lewis, Reference Travagnin and Lewis2019). Quantum computing, in contrast, poses the greatest challenge. No quantum computer with commercial or consumer utility currently exists, as most remain in experimental stages. Advances in basic research are needed before practical applications can be realized. As a result, the timeline and nature of innovation in QTs are uncertain.

As QTs move from laboratories and proof-of-concept to practical applications, governments and companies are recognizing their potential. Large technology businesses like Google (Vallance, Reference Vallance2024) and Microsoft (Bolgar, Reference Bolgar2025), alongside startups (Scheer, Reference Scheer2025) and national research programs (Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology, 2023), are investing heavily in research and development. This is often accompanied by media fanfare that emphasizes a global competition to turn prototypes into market-ready technologies. Public discourse also features gloomy narratives about QTs. One major concern, echoed in both academic literature and popular media, is that quantum computers could break current encryption standards, compromising sensitive banking and government data as well as private communications. While some scholars warn of long-term cryptographic vulnerabilities (Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, De Jong and Kop2024), media narratives often amplify these risks with apocalyptic framing, such as predictions of a ‘Quantum Apocalypse’ (Katwala, Reference Katwala2025). Another concern is that the first governments to master QTs could gain asymmetrical advantages in surveillance, espionage, and battlefield intelligence (Krelina, Reference Krelina2025), and might deny these capabilities to foreign nations or actors they deem hostile.

Although speculative, such visions can still shape public discourse and influence policymakers’ assumptions about QTs. The case of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies is instructive. In discussions about social media, AI algorithms are often blamed for pushing information that perpetuates false beliefs (Guess et al., Reference Guess, Lockett, Lyons, Montgomery, Nyhan and Reifler2020), increases social polarization (Nordbrandt, Reference Nordbrandt2021), and diminishes subjective well-being (Braghieri et al., Reference Braghieri, Levy and Makarin2022). These claims about the social impact of AI are based on legitimate concerns, yet regulatory and industry responses frequently rely on misperceptions about the true prevalence and mechanisms of harm associated with these technologies (Budak et al., Reference Budak, Nyhan, Rothschild, Thorson and Watts2024). As a consequence, policies may target the wrong issues, fail to address underlying causes, or misallocate resources. This example highlights why it is crucial to pay attention to popular narratives: they shape risk perceptions, funding priorities, and regulatory interventions, particularly when the actual capabilities and implications of a technology are not well understood.

In light of this, our study examines how QTs are portrayed in texts across three domains: media, business, and government. We analyze an extensive dataset of 2023 media articles, 163 business reports, and 36 government policy documents published over the past 23 years. We use a mixed-methods approach that combines BERTopic topic modeling, a natural language processing technique for identifying latent themes in text data, with qualitative thematic analysis to identify dominant narratives. We specifically address the following research questions:

-

• What thematic priorities dominate narratives about QTs in each domain?

-

• How does discourse about QTs compare across domains?

-

• How has discourse about QTs changed over time?

This study makes several contributions. First, we add to the growing body of scholarship about the ethical, legal, social, and policy implications of QTs (Kop, Reference Kop2023). Methodologically, we demonstrate how BERTopic modeling can be used to identify latent themes and systematically translate them into narratives. Empirically, we offer a rare quantitative and longitudinal view of discourse dynamics, in contrast to the largely qualitative focus of prior work on narratives and rhetoric. Additionally, our comparative approach fills a gap in the literature on QTs by moving beyond analyses of isolated domains to examine how narratives converge or diverge across different contexts. Lastly, the study’s findings lay the groundwork for further research into how different narratives shape the acceptance of QTs and how rhetoric about QTs is connected to actual policy implementation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, we discuss the concept of narratives and, to frame the analysis, review findings from prior literature on narratives about AI and QTs. Next, we outline the data collection and analytical approach, and finally, we present the findings and conclude with a discussion.

2. Narratives as interpretive tools

Seminal literature defines narratives as speech or text that organizes human experiences into meaningful patterns, transforming otherwise disconnected personal or historical events into coherent stories (Polkinghorne, Reference Polkinghorne1995). As cognitive tools, narratives enable individuals and collectives to construct interpretations of reality. Unlike scientific methods, which aim to produce objective, verifiable claims through observation or consistency in logical reasoning, narratives prioritize believability and plausibility over empirical truth (Bruner, Reference Bruner1991). Shaped by culture, tradition, and identity, narratives explain who we are and justify actions by articulating beliefs, desires, and intentions. Because narratives reflect culturally shared understandings, they are also contested; challenges to dominant narratives (such as those around national identity, gender roles, or historical memory) often signal social conflicts over values and power (Patterson and Monroe, Reference Patterson and Monroe1998).

Research on narratives about technologies has focused on how expectations about the future shape innovation. Beckert (Reference Beckert2016) argues that in the absence of predictable outcomes, decisions about innovation are guided by fictional expectations that make particular technological developments seem desirable or inevitable. These “little narratives” (Beckert, Reference Beckert2016, p. 174) about the future help justify investment and orient strategic decisions in uncertain environments. They are often animated by a combination of utopian hopes for progress and dystopian fears of harm or stagnation that shape how societies envision and pursue innovation.

Crucially, technology narratives do not emerge uniformly in all parts of society. The social construction of technology (SCOT) framework posits that different social groups construct divergent interpretations of technologies based on their institutional contexts, interests, and values (Pinch and Bijker, Reference Pinch and Bijker1984). What SCOT scholars call “interpretive flexibility” refers to the idea that a single technology can be understood and narrated in multiple, sometimes conflicting, ways (Pinch and Bijker, Reference Pinch and Bijker1984). For quantum technologies, this suggests that media, business, and policy actors may emphasize different aspects, problems, and opportunities, reflecting distinct organizational logics and stakeholder concerns. By examining narratives across these domains, we can identify divergent interpretations and assess their implications for governance and public understanding.

Building on this understanding of narratives, the following subsections offer a brief overview of key works and recent developments in the literature on what narratives have developed around AI and are beginning to emerge in relation to QTs.

2.1. Narratives about artificial intelligence

Prior studies examine fictional and non-fictional portrayals of AI, arguing that they serve as important sources for how people imagine technological futures (Vallor, Reference Vallor2021). A report by the Royal Society, which focuses on AI in the English-speaking West, finds that narratives often include utopian and dystopian extremes, emphasize humanoid embodiments, and exaggerate the capabilities of current AI technologies (The Royal Society, 2018). Building on this, Cave and Dihal (Reference Cave and Dihal2019) identify four fundamental dichotomies that structure public hopes and fears about AI: extending life versus losing humanity, freedom from work versus being replaced, fulfilling desires versus social disconnection, and control over others versus machines turning against humans.

Much of the recent work focuses on these extreme narratives. For example, Bory et al. (Reference Bory, Natale and Katzenbach2024), who refer to debates about large language models and public policy, distinguish between “strong AI narratives,” which envision human-like, futuristic intelligence, and “weak AI narratives” grounded in current and narrow applications. The authors conclude that popular discourse often prioritizes sci-fi-inspired AI futures over mundane, current applications. Based on interviews with AI researchers, Chubb et al. (Reference Chubb, Reed and Cowling2024) identify the same pattern, according to which AI is framed either as a universal good or an existential threat. To move beyond all-or-nothing stories and to better inform public understanding, scholars often advocate for more pragmatic narratives that emphasize context, human agency in technology design, and practical aspects of AI governance (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Mökander and Floridi2024).

AI policy and strategy papers are also a source of narrative research, perhaps a particularly important one, because they directly reflect intended governance priorities. A study of government AI strategies from Europe, North America, and Asia shows that the language used in these documents often accentuate grand narratives of innovation, global competition, or an “AI race,” positioning the technology either as a revolutionary break from the past or as part of the historical trajectory of technological progress (Bareis and Katzenbach, Reference Bareis and Katzenbach2021). Similar to these findings, an analysis of 221 AI strategy documents identifies general narratives around competitiveness, economic growth, technological sovereignty, and surveillance, while noting that governments adapt these elements to fit their local political and technological contexts (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Shehu, Dua and Wesson2025).

Another influential strand of narrative scholarship critically examines the ethical dimensions of AI. For instance, Crawford (Reference Crawford2021) criticizes portrayals of AI as an immaterial technology. Popular discourses often present AI as a purely cloud-based innovations, disconnected from physical infrastructures. This framing obscures AI’s reliance on mining rare earth minerals and on energy-hungry data infrastructures. By portraying AI as immaterial, Crawford argues, these narratives conceal the cost of computation and limit public scrutiny of environmental harm. Similarly, Munn (Reference Munn2022) examines automation narratives that present AI-driven automation as an inevitable force that will render human labor obsolete. He argues that narratives often downplay low-wage work conditions and the substantial human labor required to maintain supposedly autonomous systems, and gloss over the uneven distribution of technological benefits.

2.2. Narratives and governance in quantum technologies

Social science research on QTs is less developed than that on AI, reflecting the relatively early stage of QTs. As a result, few studies have directly focused on narratives. A notable exception is Grinbaum (Reference Grinbaum2017), who argues that narratives should be used deliberately to convey culturally familiar metaphors and historical analogies to build public trust and make QTs more relatable. Building on this, Possati (Reference Possati2024) suggests that science fiction and science journalism shape QTs’ social meaning and warns that depicting QTs as mysterious or enigmatic may hinder public understanding.

Empirical evidence on how language is used to represent QTs has been collected from different sources and contexts: interview and newspaper data on how new technology markets develop (Hilkamo and Granqvist, Reference Hilkamo and Granqvist2022), business-focused representations in YouTube videos (Godoy-Descazeaux et al., Reference Godoy-Descazeaux, Avital and Gleasure2023), and Dutch newspaper articles (Meinsma et al., Reference Meinsma, Rothe, Reijnierse, Smeets and Cramer2025). These studies highlight the usefulness of storytelling for managing complexity, the role of metaphors and analogies in sense-making, and the tension between promoting familiarity and the “strangeness” of quantum physics. Furthermore, in an experimental study with 637 participants in the Netherlands, Meinsma et al. (Reference Meinsma, Albers, Vermaas, Smeets and Cramer2024) find that communication about QTs is most effective at increasing engagement when it explains fundamental quantum physics concepts, emphasizes the benefits of the technology, and avoids simultaneously presenting both benefits and risks in a single message. Though these findings may not be broadly generalizable due to the study’s limited sample.

Relevant literature extends beyond narratives or public communication to address issues of democratization and governance. Several authors (Coenen et al., Reference Coenen, Grinbaum, Grunwald, Milburn and Vermaas2022; Seskir et al., Reference Seskir, Umbrello, Coenen and Vermaas2023) argue that while companies promote access to QTs, true openness requires broader public involvement. They highlight major barriers to this: geopolitical and military interests, portrayals of quantum mechanics as incomprehensible to non-experts, and framing quantum computing as a security threat, all of which limit transparency and justify ringfencing and restrictive development. Similarly, Ten Holter et al. (Reference Ten Holter, Inglesant and Jirotka2022) argue that if development follows the same patterns seen with classical computing, dominated by rich nations and big tech, quantum computing will exacerbate digital divides between wealthy and poor nations because access to infrastructure, expertise, and resources is unevenly distributed globally. In response to such concerns, responsible innovation frameworks have sprung up to guide the development of QTs in more inclusive and socially responsive directions (Coenen and Grunwald, Reference Coenen and Grunwald2017; Inglesant et al., Reference Inglesant, Ten Holter, Jirotka and Williams2021; Gasser et al., Reference Gasser, De Jong and Kop2024). This includes calls for soft law governance tools such as codes of conduct and voluntary regulatory programs to balance innovation with societal benefits (Johnson, Reference Johnson2019).

3. Methods and data

Our methodological approach combines computational text analysis with qualitative content analysis. First, we apply BERTopic, an advanced unsupervised machine learning technique (Grootendorst, Reference Grootendorst2022), to identify topics within the text corpus. Based on these extracted topics, we develop a codebook following thematic content analysis procedures (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008), which allows us to manually classify each topic into one of five categories: Business & Market Development, National Tech Strategies, People & Society, Politics & Global Conflict, and Technical Aspects & Applications. This categorization scheme is validated by assessing intercoder reliability among three independent coders. We then identify common narratives associated with each thematic category. This mixed-methods approach leverages the scalability and efficiency of machine learning to detect patterns in large text corpora, while retaining some of the more interpretive features of qualitative analysis. The following sections detail the data collection and pre-processing steps, describe the topic modeling process, and explain the procedures for qualitative coding and validation.

3.1. Data collection and pre-processing

We collected data from three main sources: business reports, media articles, and policy documents. For the business component, we obtained publicly available reports from the world’s 15 largest consulting firms by revenue (McCain, Reference McCain2023) and consulted the Swisscovery database (https://swisscovery.slsp.ch) for relevant articles published between January 2002 and January 2023.

For the media component, we collected English-language articles from eight national newspapers in the United States, United Kingdom, China, and India. These included The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Times of India, The Economic Times, China Daily, and South China Morning Post. We used the ProQuest TDM Studio database (https://tdmstudio.proquest.com) to search for the keywords “quantum technology,” “quantum computing,” “quantum communication,” and “quantum sensing.” The data collection covered articles published between January 2000 and August 2023.

To collect policy documents, we searched relevant government websites that publish official policy documents. These included sources from Canada (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2022), Germany (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, 2018), India (Department of Science and Technology, 2023), and the United States (National Quantum Initiative, 2025). We also consulted technology blogs such as The Quantum Insider (https://thequantuminsider.com) to track new policy publications.

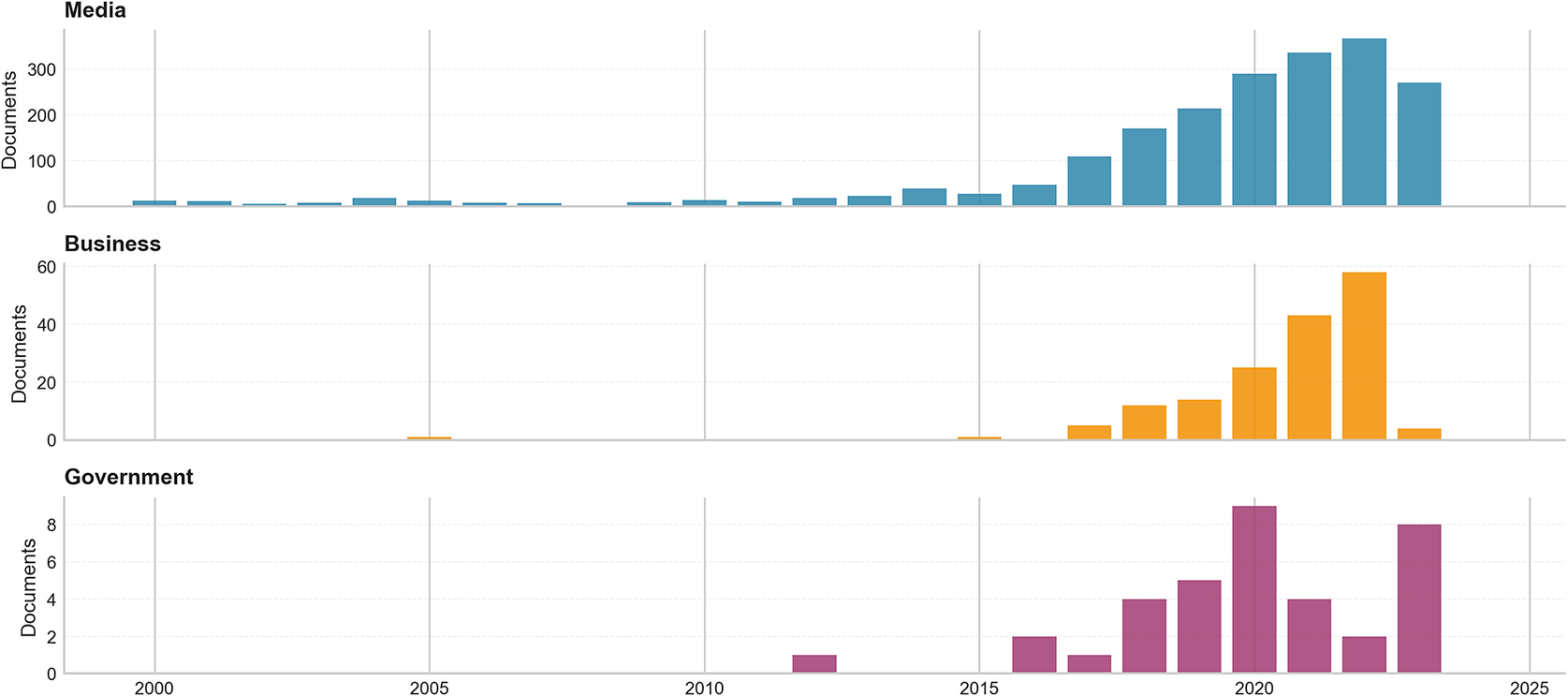

Business reports and policy documents were collected as PDF files. We converted them to TXT format and cleaned them by removing non-content elements such as headers, footers, front/back matter, and references. After cleaning, we obtained 163 business documents and 36 government policy documents. For the media articles, we initially retrieved 2754 entries. We ensured relevance through keyword searches and excluded articles unrelated to QTs. We also excluded media articles longer than 10,000 words to filter out atypical content; this length threshold was not applied to business or policy documents. We removed duplicates and highly similar articles using a Levenshtein distance cutoff of 0.3 (van der Loo, Reference van der Loo2014). The final media dataset comprised 2023 articles. Figure 1 illustrates the temporal distribution of documents across the three domains. All sectors show growth over time, with media coverage increasing substantially in recent years.

Figure 1. Temporal distribution of the document sample across media (n = 2023), business (n = 163), and government (n = 36) domains from 2000 to 2024, showing the composition and time coverage of data sources used in the analysis.

3.2. Topic Modeling

To identify topics in the documents, we applied BERTopic to the cleaned dataset. BERTopic uses clustering algorithms and class-based term frequency-inverse document frequency (c-TF-IDF) scores to generate coherent topics, producing more coherent and interpretable topics than traditional methods like LDA or STM (Grootendorst, Reference Grootendorst2022). We split each document into individual sentences and fed them into BERTopic, resulting in 22,005 sentences from 163 business-focused documents, 67,012 sentences from 2023 media articles, and 14,806 sentences from 36 government policy documents. We used the all-distilroberta-v1 sentence embedding model (Hugging Face, 2021), UMAP for dimensionality reduction, and HDBSCAN for clustering. We tuned the HDBSCAN parameters using TopicTuner (Drob-Xx, 2023) and manual inspection (Grootendorst, Reference Grootendorst2021) to balance coherence and topic diversity. After parameter tuning and post-processing, BERTopic returned 51 topics for business documents, 55 for media articles, and 51 for government policy documents.

There are several reasons why we chose to conduct the analysis at the sentence level. First, this approach offers greater detail and allows the topic model to capture fine-grained themes that might be overlooked in longer text segments. Long documents, such as business reports or policy statements, often contain multiple themes within a single document. In such cases, sentence-level analysis enables more granular topic discovery than document-level approaches do. Second, because the documents in our corpus vary in length, they benefit from the standardized analytical units that sentence-level processing offers. This prevents bias in topic assignment due to document length. Although this approach risks fragmenting a document’s broader context, our mixed-methods design mitigates this issue by employing qualitative analysis in the final stage to re-contextualize the topics and identify overarching narratives.

3.3. Thematic classification and narrative identification

The topics generated by the topic modeling procedure formed the basis of a manual classification task. Each topic was assigned to one of the following five thematic categories: Business & Market Development, National Tech Strategies, People & Society, Politics & Global Conflict, and Technical Aspects & Applications. These categories were developed using a hybrid deductive-inductive approach. Guided by previous research (see Section 2), we created an initial classification scheme that we iteratively refined through the manual review and collaborative discussion of the identified topics.

To ensure the reliability of this thematic framework, three coders performed multiple rounds of classification. Each coder was given the topic label, the 15 most representative keywords, and 3 representative sentences for each topic. The coders then independently assigned each topic to one of the five themes. The final inter-coder reliability assessment showed strong agreement, with Krippendorff’s alpha values of at least 0.8 for each category, meeting the standard for high reliability (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorff2019).

The identification of narratives within each theme followed a collaborative process. First, we reviewed all topics assigned to each theme, examining their keywords and representative sentences for recurring patterns and storylines. Second, we identified conceptual links between related topics and grouped them into narrative clusters. Third, we validated these narratives by returning to the original documents to ensure that our interpretations accurately reflected the source material. This iterative process was conducted collaboratively by all three coders to ensure that narrative identification was grounded in empirical patterns rather than individual interpretation. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and reference back to the data until consensus was reached.

3.4. Data and sampling limitations

Several methodological limitations of this study should be noted. First, our sampling strategy reflects specific geographic perspectives that may not capture the full global landscape of quantum technology discourse. For instance, the media corpus is composed entirely of English-language newspapers from the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and India. While these countries are leading players in quantum technology development, this focus may omit regional perspectives particular to the European Union, Japan, Australia, or other nations with substantial quantum research programs. Future research could expand the geographic scope to provide a more comprehensive comparison.

Second, the business corpus is limited to reports from the 15 largest consulting firms by revenue. Although this approach captures popular and influential business discourse that is likely to shape corporate decision-making, it may not reflect the perspectives of hardware and software companies, startups, or smaller industry actors who are often at the forefront of innovation. These entities may have different views on commercialization strategies, technical priorities, and ethical considerations that are not represented in our sample.

Third, the policy document sample (n = 36) includes documents from over 20 countries across multiple regions, including Western nations, Asian economies (China, Japan, Singapore), and representation from the Middle East (Saudi Arabia), Africa (South Africa), and Russia. However, it is heavily weighted toward Western countries and is substantially smaller than the media corpus. The findings for the policy domain are therefore more illustrative than exhaustive and should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

Finally, our sentence-level approach to topic modeling, while enabling granular thematic discovery across documents of varying length, carries the risk of fragmenting broader contextual meaning. Although our mixed-methods design mitigates this through qualitative validation, some subtle distinctions in how arguments unfold within individual documents may be lost. Document-level research could therefore provide additional insight into how narratives are constructed across entire texts.

4. Results

As outlined above, we identify five recurring themes that structure the discourse on QTs: Technical Aspects and Applications, Politics and Global Conflict, People & Society, National Technology Strategies, and Business and Market Development. In the following sections, we present the findings in line with our research questions and show how each theme is articulated across media, business, and policy domains.

4.1. What thematic priorities dominate narratives about QTs?

The “Technical Aspects & Applications” theme covers the fundamental technical details, mechanics, and practical implications of emerging QTs across application domains and industries, including qubits, cryptography, AI, drug development, and logistics. Texts within this theme often portray QT as overcoming the limitations of classical computing by exploiting quantum mechanical principles. The theme also captures how discussions about technical foundations are closely connected to and mentioned alongside practical uses of QTs.

A characteristic narrative associated with this theme is that of “revolutionary technological advancement.” Here, QTs are described as a radical force that will transform the technological landscape and enable substantial progress across businesses and industries. The following excerpt provides an example:

Quantum technology, which enables the manipulation of atoms and sub-atomic particles, will allow for a new class of ultra-sensitive devices with key potential to profoundly impact and disrupt significant applications in areas such as defense, aerospace, industrial, commercial, infrastructure, transportation and logistics markets. (Business & Industry Report, 2020)

Another popular narrative is “challenges to traditional cybersecurity.” This narrative references, among other things, Shor’s algorithm, an quantum algorithm that can potentially break any existing classical cryptographic method used to secure digital communications. It posits that as QTs are increasingly integrated into practical applications, traditional data security, privacy, and overall cybersecurity frameworks are at risk. Consequently, this narrative includes calls for the development of post-quantum cryptographic techniques that are immune to quantum-based intrusions. The following representative sentences illustrate this point:

Quantum computers have the potential to break existing encryption security algorithms; governments and organizations alike must therefore ensure encryption is quantum-ready. (Business & Industry Report, 2021)

A third common narrative is “Quantum Mysteries and Magical Phenomena.” This narrative emphasizes the puzzling aspects of QTs that contradict everyday intuition about the behavior of physical objects. It refers to concepts such as entanglement, which Einstein famously described as “spooky action at a distance” and the paradoxical nature of Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment in order to frame QTs as mysterious and reality-altering. This kind of narrative often invites readers to rethink the nature of reality itself or the future of communication technology. It is noteworthy that technical terminology, such as the term “magic states” in quantum computing, can contribute to this perception, even when the name has a precise scientific meaning unrelated to mysticism. Consider this representative excerpt:

Another property, called entanglement, links two or more particles into a cooperative amalgam that Einstein dubbed spooky action-at-a-distance. (News Coverage, 2022)

The “Politics & Global Conflicts” theme encompasses geopolitical dynamics, and international relations. It addresses the interactions and tensions between different nation-states and world regions and examines how QTs intersect with the challenges and opportunities that arise in these relationships. The theme discusses QTs not only as an advancement in computational capabilities, but also, and chiefly, as a central element in power relations between nations.

A common narrative is that of Sino-US rivalry, which reflects the geopolitical competition between the United States and China for technological dominance. This narrative often highlights the U.S. government’s imposition of export controls and investment restrictions, typically framed as efforts to curb China’s technological development and safeguard U.S. national security interests. It also frequently addresses the decoupling of research and development ecosystems between major political and economic blocs.

President Joe Biden signed an executive order on Wednesday to block US dollars from flowing to Chinese semiconductors and microelectronics, quantum information tech and certain artificial intelligence systems — the latest move to blunt China’s access to such technologies. (News Coverage, 2023)

A more general but related narrative is “Quantum Diplomacy.” It addresses the role of QTs in international conflicts and alliances beyond the Sino-American rivalry. QT is depicted as a bargaining chip in geopolitical strategies: imposing economic sanctions and enforcing technology embargoes to restrict access as well as promoting cooperative efforts to share innovations with allies. The narrative illustrates how QTs are deployed as part of an international relations playbook that focuses on gaining high-tech advantage and political influence.

The growing realisation of the emerging opportunities has already kick-started an international race to turn the recent excellent achievements of quantum science into a national competitive advantage in Quantum Technologies. (Government Policy Document, 2019)

The “People & Society” theme explores how QTs may impact societal issues, contribute to sustainable development, and benefit society as a whole. This includes addressing challenges such as gender inequality and ensuring responsible technology development. A primary narrative within this theme is “Education Reform and Workforce Development.” This narrative presents QTs as necessitating extensive changes in education and training approaches. It emphasizes creating learning environments capable of producing a quantum-ready workforce and advocates for integrating quantum technologies into curricula at all levels. As stated in this policy document:

The creation of a learning ecosystem embracing the concepts of quantum physics at all levels ranging from school up to the working environment is required, not just for a quantum-ready workforce to emerge, but for a well-informed society with knowledge and attitudes towards the acceptance of quantum technologies. (Government Policy Document, 2020)

Another prominent narrative within this theme is “Promoting Gender Equality,” which draws attention to gender balance issues in research and development activities. The narrative highlights how female researchers are often marginalized in research and technology development. Various documents, including those from the European Quantum Flagship initiative, explicitly advocate for adopting norms and policies to address disparities in gender visibility and representation.

Gender equity in conferences: through the implementation of the conference charter and the promotion of the visibility of women in quantum, Quantum Flagship related conferences will reach full gender equality in their speaker, moderators and panels (similar number of male and female participants, about 50-50%). (Government Policy Document, 2020)

The “Responsible Technology Development” narrative calls for ethical development practices and highlights QTs’ ability to address global challenges. It often references QTs’ role in achieving sustainable development goals, such as increasing renewable energy production. Imagined applications include optimizing wind turbine designs, improving solar panel efficiency, and increasing overall energy efficiency across power systems. However, it also points to potentially harmful societal consequences, some of which are extrapolated from past experiences with AI—such as misinformation or discrimination caused by biased algorithms.

To meet the increasing societal demands for trustworthy technology, the future of quantum technologies should be informed by lessons learned from previous digital ethics failures (for example, from instances where individuals’ data was misappropriated or misused, where algorithms were employed to amplify misinformation and hateful content online, and where marginalized groups faced added discrimination through the use of unrepresentative data sets and unfair models). (Business & Industry Report, 2022)

The “National Tech Strategies” theme focuses on initiatives and policies adopted by governments to advance and establish local QTs industry and related fields such as semiconductor manufacturing. It features discussions on national research funding, government-sponsored quantum strategies and partnerships. In contrast to the “Politics & Global Conflict” theme, it spotlights the more domestic aspirations of governments.

A commonplace narrative related to this theme is the “Quantum Sovereignty” narrative. Here, the debate focuses on the active management of capabilities to establish national leadership roles. The overriding priorities for building capabilities articulated are primarily twofold: economic interests and national security. In the narrative, speakers often assert the need for collaboration across academia, industry, and government to foster an ecosystem for innovation. However, it also frequently links the pursuit of broader societal values, such as fairness and social inclusion, to QTs.

Finally, it is imperative that while developing the QIS (quantum information science) enterprise in the United States, the Government also protects intellectual property and economic interests, seeks to understand dual-use capabilities, and supports national-security-relevant applications. (Government Policy Document, 2018)

The “Business & Market Development” theme covers topics related to corporate strategies, private investment, and commercialization of QTs. It also captures aspects of companies’ recent technological breakthroughs and the challenges of bringing new technologies to market.

A key narrative is the “Quantum Gold Rush.” It presents QTs as an investment opportunity, highlighting the large-scale investments being made to disrupt industries and create new markets. This narrative encompasses not only the research and development efforts of established technology corporations like Microsoft and Google and a growing ecosystem of quantum-focused startups, but also massive government initiatives aimed at building the underlying industrial capacity. These policies, while sometimes focused on adjacent industries like semiconductors, are framed as essential for securing a future quantum advantage. For instance:

No less ambitious but more controversial is the bill’s provision of dollar 52 billion in aid to the semiconductor industry, most of which would go to subsidize new factories in the United States. (News Coverage, 2022)

Building on these investment trends, another recurring narrative emphasizes the importance and urgency of actively engaging with QTs today to realize its full potential tomorrow. We call this the “Getting Quantum Ready” narrative. It acknowledges current immaturity and uncertainty but presents the technology as a promising frontier. It specifically prompts business stakeholders to prepare for the eventual maturation of QTs to avoid being caught off guard by innovation in QTs and to capitalize on the opportunities it presents. These complementary narratives, “Quantum Gold Rush” and “Getting Quantum Ready,” frame the commercial landscape of QTs as both lucrative and strategically crucial for long-term business viability.

4.2. How does discourse about QTs compare across domains?

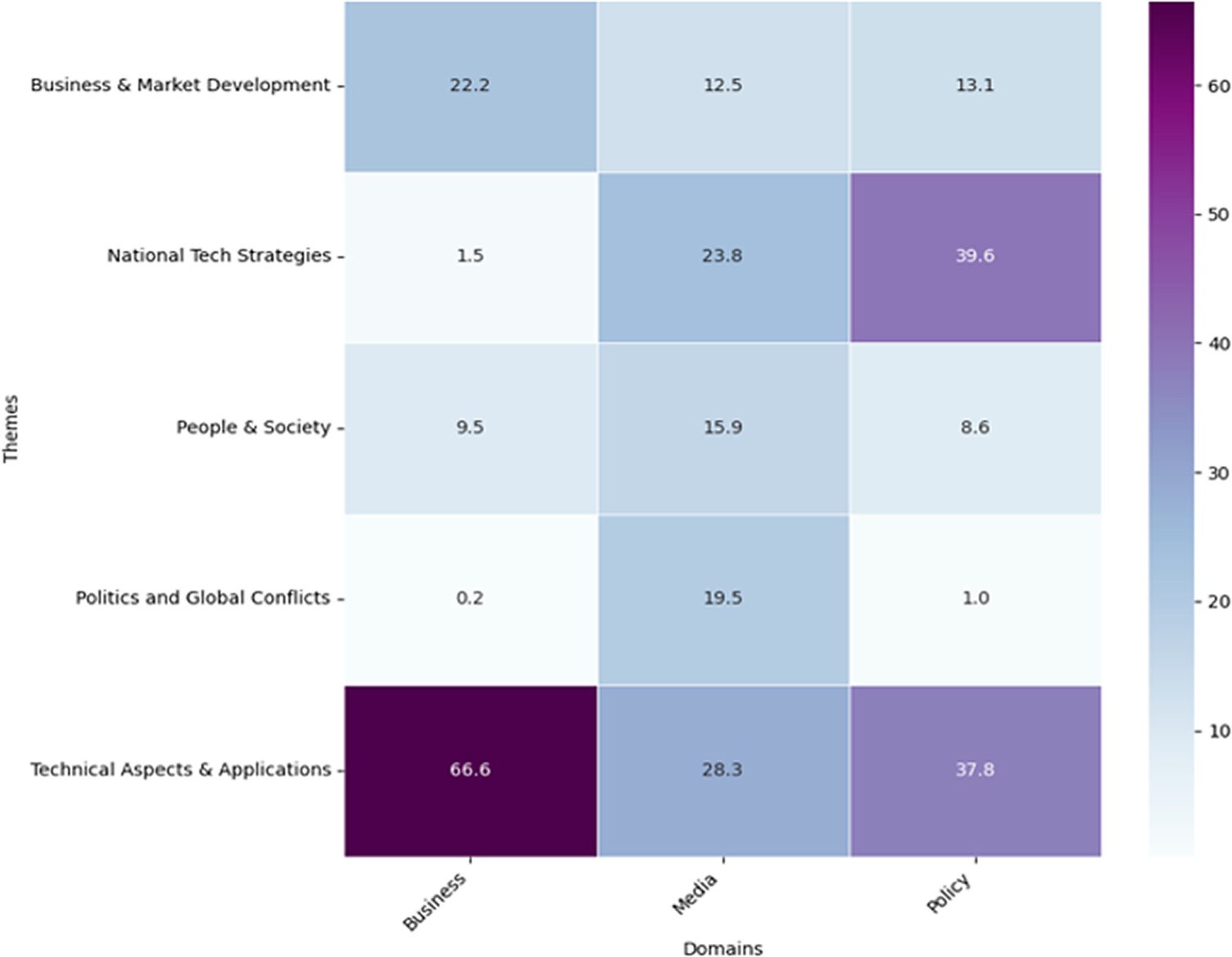

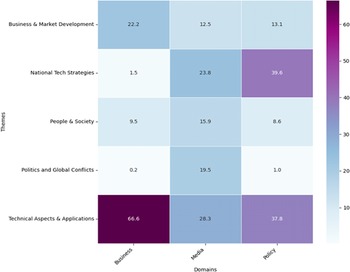

To quantify our observations, Figure 2 presents a heat map showing the percentage distribution of themes across the data sources. The percentages shown represent the proportion of sentences within each domain that were classified under a given theme. For example, the 28.3% value for “Technical Aspects & Application” in media documents means that 28.3% (or roughly 18,964) of the 67,012 sentences analyzed from media documents were part of topics that our thematic analysis categorized under “Technical Aspects & Application.” The figure shows that Media sources cover a diverse set of themes, though certain topics receive somewhat greater focus. The main focus is on “Technical Aspects & Applications” (28.3%), “National Technology Strategies” (23.8%), and “Politics & Global Conflicts” (19.5%). “People & Society” (15.9%) and “Business & Market Development” (12.5%) are also present, but to a lesser extent. Business reports primarily concentrate on “Technical Aspects & Applications” (66.6%), followed by “Business & Market Development” (22.2%). Other themes are scarcely covered. In stark contrast to the technical aspects, business reports barely touch on themes and narratives about “National Tech Strategies” (1.5%) or “Politics & Global Conflicts” (0.2%). Government texts give overwhelming attention to “National Tech Strategies” (39.6%) and “Technical Aspects & Applications” (37.8%). Other themes, such as “Business & Market Development” (13.1%), “People & Society” (8.6%), and “Politics & Global Conflicts” (1.0%), receive less emphasis.

Figure 2. Thematic focus across media, business, and government text corpora, shown as percentage distribution. The values shown represent the percentage of sentences within each domain that were assigned to a given theme.

4.3. How has discourse about QTs changed over time?

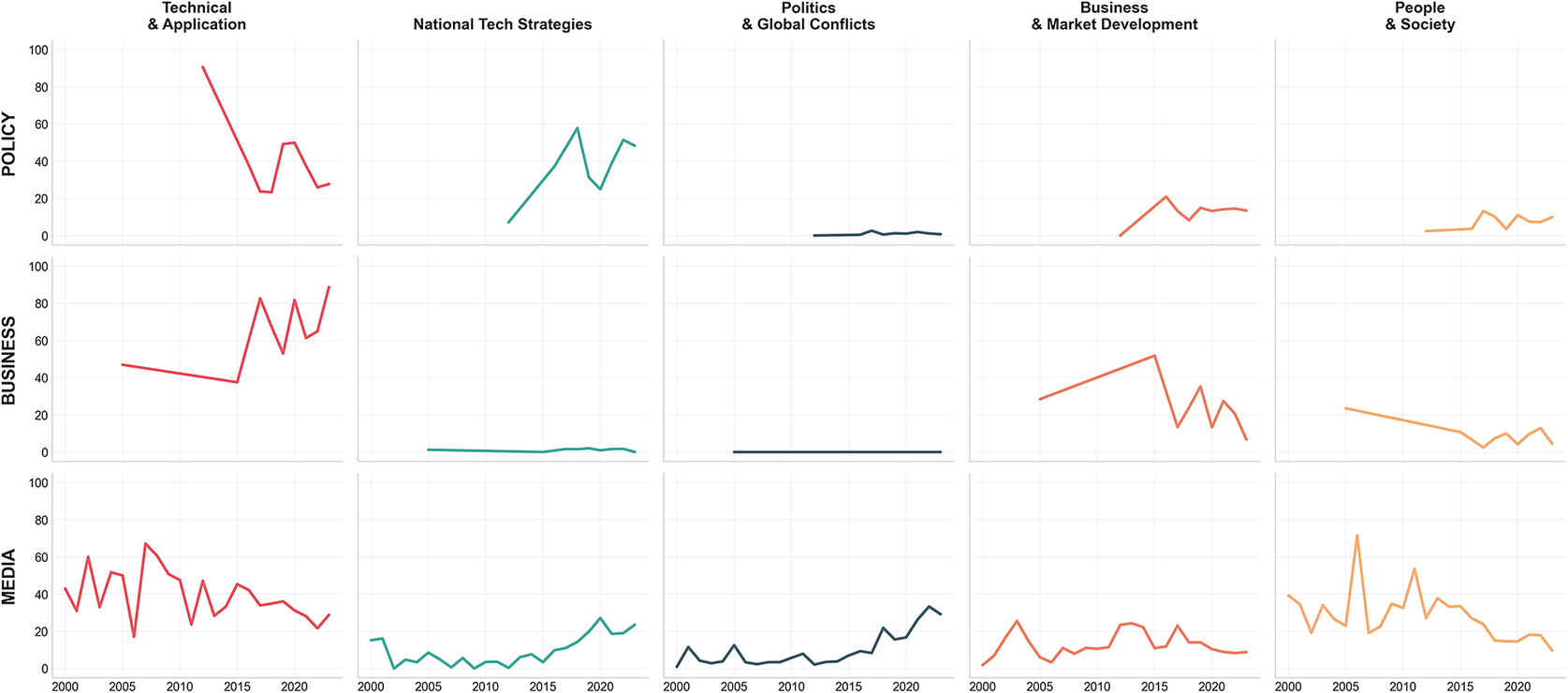

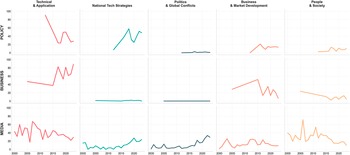

Figure 3 illustrates how the thematic focus has evolved across the policy, business, and media sectors. A notable trend is the growing emphasis on strategic and national planning, particularly through increasing references to “National Tech Strategies” in both policy and media discussions. In the policy domain, “Technical Aspects & Applications” and “National Tech Strategies” dominate throughout the period. Other themes remain consistently low.

Figure 3. Temporal trends in thematic focus across policy, business, and media domains. Each panel displays the percentage share of a specific theme over time within each domain. Rows correspond to the three domains analyzed, columns represent the five identified themes. Notable patterns include the dominance of Technical Aspects in business discourse, the rise of National Tech Strategies in policy documents, and greater thematic diversity in media coverage compared to business and policy documents.

In the business domain, “Technical Aspects & Applications” maintains a strong and increasing presence, underscoring businesses’ enduring interest in technical innovation. “Business & Market Development” increases steadily until around 2015 before declining in recent years. Other themes, including “People & Society” appear sporadically but remain marginal.

Media coverage shows the most dynamic change over time. While technical issues remain important, there is a gradual increase in attention to “National Tech Strategies” and “Politics & Global Conflicts,” suggesting an increased awareness of the strategic and geopolitical dimensions of QTs. In contrast, coverage of “People & Society” shows a downward trend in recent years, which may indicate a shift away from social considerations towards geopolitical perspectives.

5. Discussion

Our analysis reveals three key findings that warrant closer attention. First, public discourse about QTs primarily focuses on explaining their fundamental principles and technical capabilities. Narratives from business, media, and policy sources often emphasize the technologies’ potential to outperform traditional computing or their applicability to sectors such as healthcare, cybersecurity, and energy. This is reflected in the dominance of the “Technical Aspects & Applications” theme across all domains.

From a social construction perspective, this convergence on technical narratives reflects a shared need among diverse stakeholders to establish what quantum technologies are before debating what they should become. Because QTs remain largely pre-commercial and their quantum mechanical foundations defy everyday intuition, different groups (journalists explaining to publics, businesses pitching to investors, and governments justifying research funding) must first engage in interpretive work to make these technologies understandable and credible. The dominance of technical narratives thus represents an early stage of social construction, where establishing basic legitimacy and feasibility takes precedence.

Second, although technical narratives are prevalent across domains, we observe divergences in thematic emphasis that reflect what SCOT scholars call “interpretive flexibility” (Pinch and Bijker, Reference Pinch and Bijker1984). Business discourse is almost entirely devoid of political considerations, while both business and government texts pay comparatively little attention to societal concerns. These patterns unlikely to be arbitrary; they reflect the organizational logics and institutional imperatives of different social groups. Business actors construct QTs primarily through a commercial lens, emphasizing market opportunities, competitive advantage, and return on investment. Similarly, government actors construct QTs through a strategic lens focused on national security and economic competitiveness, which downplays social considerations such as equity and accessibility that do not directly serve these priorities. In contrast, media narratives, which aggregate and translate across multiple stakeholder perspectives, display greater thematic diversity.

These interpretive differences have practical consequences. The absence of political considerations in consulting firm reports, whether due to a genuine blind spot or deliberate avoidance, is noteworthy. By presenting QTs exclusively as commercial opportunities in public-facing materials, these firms overlook regulatory dynamics, policy developments, and geopolitical tensions that will likely shape market conditions. Firms may avoid politically sensitive topics to maintain client relationships or their commercial perspective may simply filter out non-market dynamics. Regardless of intent, this absence from business discourse limits the range of perspectives available to organizations on quantum innovation, potentially leaving them unprepared to consider the political dimensions of QTs.

Similarly, the neglect of social issues in business and government discussions could undermine public legitimacy, though testing this hypothesis would necessitate a direct examination of public perceptions. Because the infrastructure for QTs is likely to remain highly specialized and concentrated among a few actors, concerns about accessibility, equity, and ethical governance may influence how the public perceives fairness and trustworthiness. If the public perceives that these considerations are being overlooked, as our analysis of business and policy documents suggests, this could increase risk perceptions and resistance to QTs. From a SCOT perspective, this would represent a failure to engage with the interpretive concerns of the general public, who may view QTs primarily through social and ethical lenses rather than technical or strategic ones. Addressing these gaps in current discourse could align quantum innovation with socially desirable outcomes and strengthen its public legitimacy.

Our third finding concerns the contrast between QT and AI narratives. Public narratives about AI often swing between utopian and dystopian extremes. This influences both policy and public understanding, sometimes leading to unrealistic expectations. In contrast, discourse about QTs is more measured. Although there is enthusiasm about potential applications and increasing media attention, we do not observe the same polarization or exaggerated speculation.

This difference may reflect the early developmental stage of QTs and the absence of consumer-facing applications, which has prevented widespread public speculation. However, the growing emphasis on geopolitical competition, particularly the framing of QTs as a zero-sum “quantum race” between nations, deserves scrutiny. From a social construction perspective, narratives shape the trajectories of technological development (Beckert, Reference Beckert2016). In fact, conflict-driven narratives about QTs are already producing tangible effects. For example, policymakers have enacted export controls and investment restrictions, researchers face growing limitations on international collaboration, and the quantum innovation ecosystem is fragmenting along geopolitical lines. These developments illustrate how dominant narratives can become self-fulfilling prophecies. From an SCOT perspective, this represents a narrowing of interpretive flexibility, where one particular construction of QTs, as instruments of national power and security, increasingly crowds out alternatives that would emphasize open science, international cooperation, or shared responses to global challenges.

6. Conclusion and outlook

Our analysis shows that public conversations about QTs emphasize different issues depending on the institutional context. Overall, the conversation is characterized by technical narratives that highlight the transformative potential of QTs for businesses and society. However, certain issues receive limited emphasis: business discourse rarely addresses geopolitical or regulatory dimensions, and both business and government narratives tend to devote little attention to concerns such as accessibility, equity, and ethical governance. Drawing on the social construction of technology framework, we show that these patterns reflect how different institutional contexts shape interpretive frames, with practical implications for governance and public legitimacy.

The good news is that compared to discussions around AI, narratives about QTs are more restrained. They tend to avoid the speculative extremes (either dystopian or utopian) that often characterize AI discourse. This moderation may foster more grounded expectations about QTs. In contrast, the growing emphasis on geopolitical competition raises concerns about the potential fragmentation and retrenchment of research and innovation activities.

Methodologically, this study combines computational topic modeling with thematic coding to provide a broad, cross-sectoral perspective on public discourse. While this approach captures dominant themes and long-term trends, it necessarily abstracts from the in-depth, context-specific insights of purely qualitative research. Future work could build on these findings by focusing more closely on individual narratives, using methods such as interviews or case studies to examine how they are constructed, contested, and interpreted within specific institutional, professional, or cultural settings.

Data availability statement

Due to licensing restrictions, the data are not publicly available but may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers and participants of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) for their feedback and suggestions provided for an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author contribution

Conceptualization-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Conceptualization-Supporting: M.M.; Data Curation-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Formal Analysis-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Funding Acquisition-Lead: M.M.; Investigation-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Methodology-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Project Administration-Equal: V.S., Resources-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Software-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Supervision-Equal: G-M.P.; Supervision-Lead: M.M.; Validation-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Visualization-Equal: V.S., C.M., G-M.P.; Writing – Original Draft-Equal: V.S., Writing – Review & Editing-Equal: V.S.

Funding statement

This research was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (205695).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The research meets all ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the study country.

AI statement

AI tools were used at certain points in the research process. Claude Sonnet 4.5 was used to improve the clarity of some written sections, brainstorm analytical approaches, and draft Python code for the BERTopic analysis. All LLM-generated outputs were reviewed, revised, and verified by the authors. The core research design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and conclusions are entirely the work of the listed authors.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.