Policy Significance Statement

Providing the status of AI governance in the MENA region to policymakers is essential for creating a regulatory framework that balances innovation with ethical considerations, economic development, and the well-being of society. It enables proactive decision-making to harness the benefits of AI while addressing potential challenges.

1. Introduction

Governance is a major obstacle companies and governments face (Microsoft, 2018). Following advances in the benefit of integrating artificial intelligence (AI) models and realizing the challenges related to generating and managing large amounts of data in recent years, organizations are increasingly expanding their use of AI technologies. AI has become increasingly popular as organizations consider how they can use AI to improve customer experience, increase operational efficiency, or automate processes. Likewise, public health authorities have started to carefully consider the opportunities and challenges of using AI in improving health systems. Folding into these worldwide initiatives, the MENA region is conducting important debates on integrating AI approaches while considering their regional specificities. However, AI has evolved into a strategic, economic, and military issue, with power concentrated in a few American and Chinese multinationals, threatening state sovereignty (Miailhe, 2018). The North–South digital divide is widening, as many developing countries lag in AI adoption. Most nations with national AI strategies are in the Northern Hemisphere, while the MENA region, including Maghreb countries, lacks clear plans and investment in data governance. Challenges like limited data, infrastructure, national strategies, and human capital persist despite MENA’’s innovation potential, tech-savvy youth, and active startup ecosystems that offer promise for AI growth (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020).

The increasing use of AI has raised questions about the ethical, equitable, and accountable use of technology that aids or substitutes for human decisions. When implementing an AI system, it is essential to carefully manage the AI life cycle, data governance, and the machine learning model to avoid unintended consequences not only on an organization’’s brand reputation but, more importantly, on employees, individuals, and society as a whole. When adopting AI systems, it is necessary to have robust ethical and risk-management frameworks in place. AI governance captures the necessity to integrate these considerations into a framework to conduct responsible AI. We need governments to implement responsive regulatory frameworks that enforce AI governance.

In this commentary paper, we explore various aspects of AI governance, starting with an examination of AI governance as a framework for ensuring the responsible use and development of AI as a technology. We will highlight the gaps in AI governance implementation in the MENA region, addressing the challenges these countries face to align with global standards. The paper will also review current efforts in global AI governance within MENA countries, providing examples of AI strategy setups in nations such as Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Jordan. Additionally, we will delve into key initiatives aimed at launching AI ecosystems in three North African countries (Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria), as well as Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, showcasing the diverse approaches to fostering AI development across the region. This commentary paper mapping of the AI ecosystem and strategies was based primarily on the reports by Mejri (Reference Mejri2020) and Oxford Insights (2023), as well as the following sources: government bodies (ministries, public organizations for information technology, and innovation support structures like incubators and tech hubs), AI-focused startups websites, technology and innovation associations, and personal communication.

2. AI governance as a framework for responsible AI

A government ought to possess a strategic outlook for AI development and management, backed by suitable regulations and a focus on ethical concerns (governance and ethics). Additionally, it should cultivate robust internal digital capabilities, encompassing the skills and methodologies that enhance its ability to face the challenges of emerging technologies.

Governance and Ethics are critical dimensions for AI development in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (Oxford Insights, 2023). These areas are emerging as key challenges that need to be addressed for the region’’s advancement in AI. Despite their leading roles in AI adoption, the UAE and Saudi Arabia have not made as significant progress in establishing strong governance frameworks and ethical standards as might be anticipated. Both countries face substantial challenges in these areas and need to enhance their efforts to build effective and responsible AI systems (Oxford Insights, 2023).

3. Gaps in AI governance implementation in the MENA region

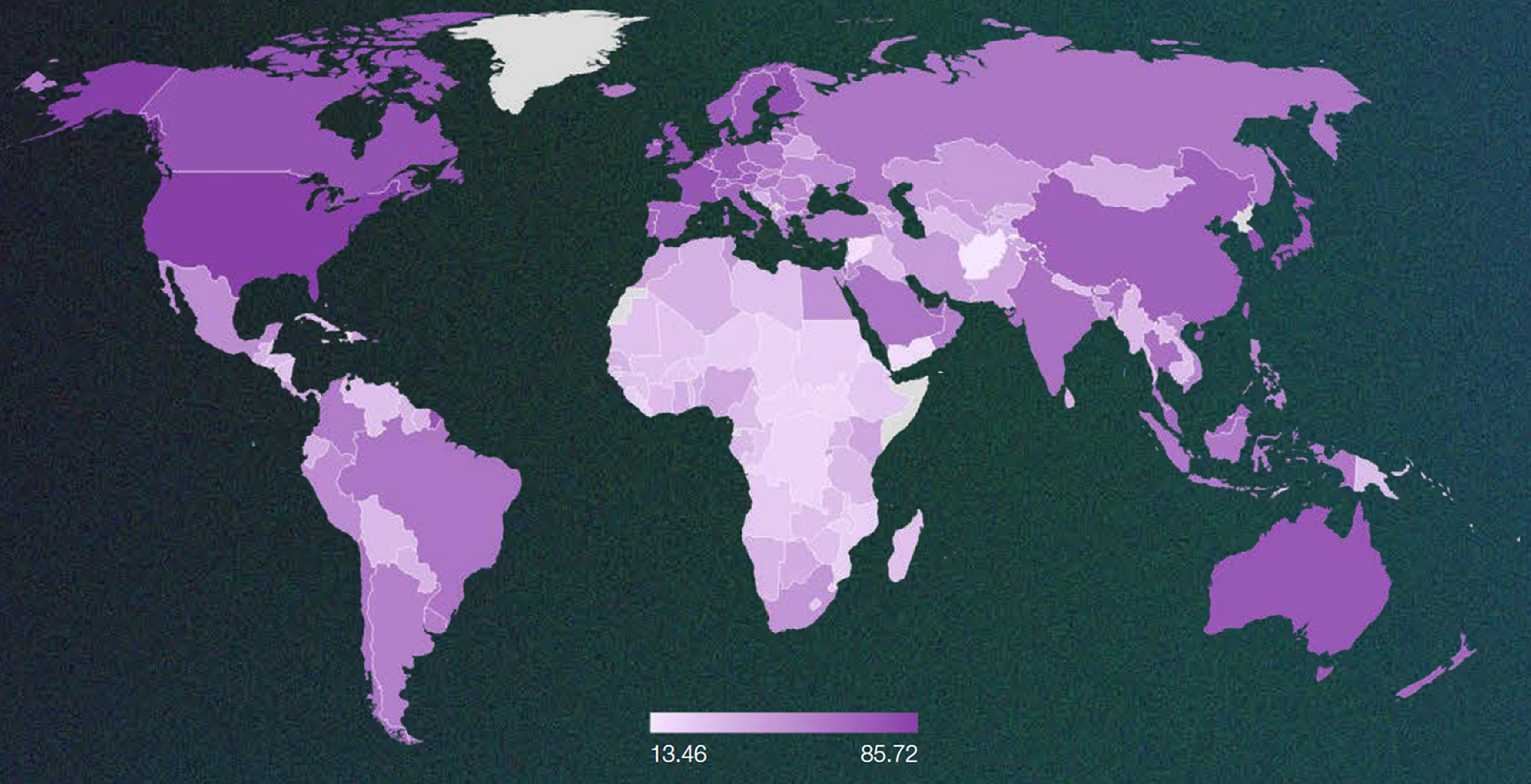

The efforts made in MENA countries fall short of the expectations and challenges associated with the AI revolution; the North-South divide and the digital gap persist. Looking at the map of countries with national AI strategies, the overwhelming majority are still highly concentrated in the North of the hemisphere (Figure 1). In addition, governments in the MENA region do not invest in the structuring and governance of data produced by state administrations, businesses, or society. Like most countries in the South, countries in the MENA region face many obstacles related to data availability, infrastructure, and human capital. However, (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020) mentioned that in the economies of the three MENA countries, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, the potential for overcoming these obstacles is there; owing to the presence of a strong capacity for innovation, a youth eager to learn and apply AI-driven approaches, a dynamic startup ecosystems open to new technological trends as well as a large community of diaspora, specialized in AI, ready to help.

Figure 1. National AI strategies in the 2022 AI Index Rankings. The ranking is based on 39 indicators across 10 dimensions, constituting three pillars: the Government pillar, the Technology Sector pillar, and the Data & Infrastructure pillar (Oxford Insights, 2023).

Another facet of responsible AI, regarded as essential within the MENA region, pertains to the localization of AI development. Kais Mejri, former Director General for Innovation and Technological Development at the Ministry of Industry and SMEs in Tunisia, and Golestan Radwan, advisor to the Minister for AI at the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology in Egypt, said that this is a common concern among the neighboring North African countries (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020; Oxford Insights, 2023). As AI continues to gain broader acceptance throughout the MENA region, both experts suggest that these countries collectively emphasize the preservation of their cultures, the importance of Indigenous languages and religion, and safeguarding users from AI products that lack local data training (Arab Barometer, 2023; Pew Research Center, 2018). Sara Zaaimi, Deputy director for communications at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East programs, highlighted her concern about MENA citizens’ perception and behavior towards AI: “The unavoidable debate is how compatible AI can be with Arab societies?” (Zaaimi, Reference Zaaimi2023 ). She suggested that it would be valuable to investigate how these cultures interpret transhumanism and justify the possible transition from human dominance to the era of all-knowing machines. However, it would be an oversimplification to underestimate the resourcefulness and adaptability of Arab youth, considering their adept utilization of social media for political activism. These mutual priorities, alongside other common challenges the region faces, underscore Golestan Radwan and Mejri’s belief in the untapped potential of cross-border collaboration to develop shared solutions for MENA countries. Progress in this context, such as establishing a common AI Strategy for Arab countries, has the potential to significantly advance AI readiness in the near future (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020; Oxford Insights, 2023).

Digital economy (or payment) is key to successful AI implementation due to its role in providing real-time transactional data, which aids in training AI for pattern recognition and prediction. Companies like Visa and Mastercard leverage this data for fraud detection and personalization. Additionally, digital payments integrating AI technologies enhance payment processes, as seen with PayPal’s fraud detection and Square’s insights. AI also boosts security by detecting fraud, exemplified by Stripe’s monitoring for example. Moreover, AI-driven analysis of consumer behavior enables personalized services, and the growth of digital payments supports scalable innovations like mobile banking and blockchain. Overall, digital payments are crucial for advancing AI through data, security, personalization, and scalability.

The World Bank (2022) highlighted a digital paradox, unique to the MENA region: “While MENA countries’ populations have embraced social media use – more than expected given their levels of GDP per capita – the populations’ usage of the Internet and digital tools like mobile money to pay for services is lower than expected given country income levels.” Efforts are required to boost the supportive regulatory structure for e-commerce dealings, encompassing electronic signatures, safeguards for data privacy, and cybersecurity. Addressing the digital paradox by giving precedence to necessary reforms aimed at boosting the adoption of digital payments is vital for expediting the transformation of the digital economy (The World Bank, 2022). It has been speculated that reluctance to employ digital technology for financial transactions often stems from a deficiency in societal trust in low and middle-income MENA countries towards government and corporate entities, along with regulatory obstacles that impede the digital transformation process.

4. Current efforts in global AI Governance in MENA countries

The government’’s readiness index for AI ranks governments worldwide based on their willingness to implement AI in providing public services to their citizens (Oxford Insights, 2023). Since the initiation of the Government AI Readiness Index in 2017, the British firm Oxford Insights has observed an expansion of AI strategies on a global scale, signifying the acknowledgment of AI as a pivotal technology by governments. Annually releasing the Government AI Readiness Index provides an overview of global progress. The globe is divided into nine regions, utilizing a combination of UN and World Bank regional groupings. Each region undergoes a thorough analysis, incorporating insights from interviews held with regional experts, index scores, and desk research. The ranking is based on 39 indicators across 10 dimensions, constituting 3 pillars: the Government pillar, the Technology Sector pillar, and the Data & Infrastructure pillar.

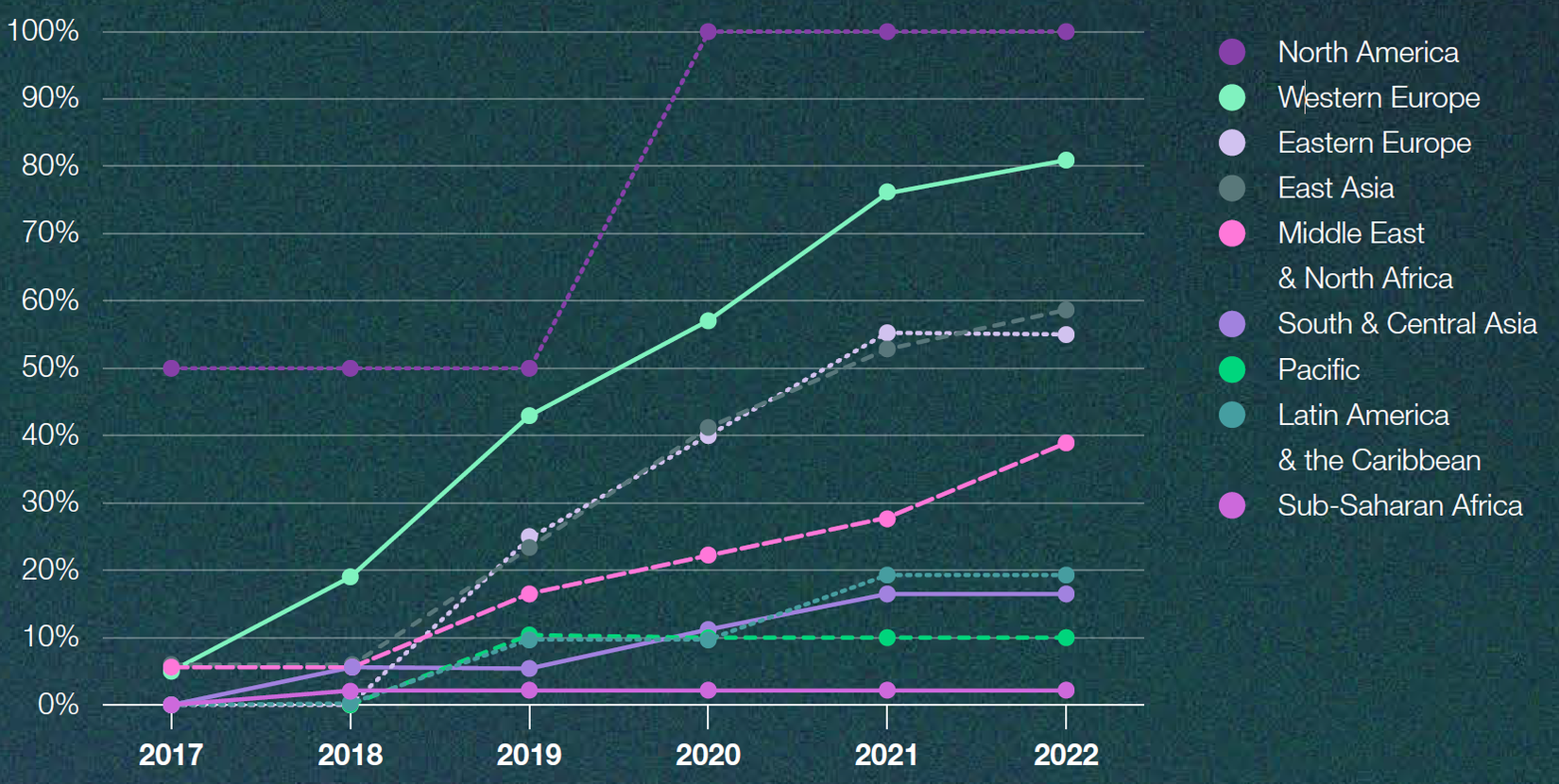

According to the 2022 Index Rankings, since 2020, the regions of MENA and East Asia have experienced the most significant growth in the number of countries adopting national AI strategies (Figure 2) (Oxford Insights, 2023).

Figure 2. Percentage of countries in each region with published national AI strategy (Oxford Insights, 2023).

The MENA region exhibits the second-widest spectrum of scores among all global regions. A significant divergence in scores is apparent between Middle Eastern nations, with an average of 51.14, and North African countries, with an average of 38.59. Nevertheless, Egypt and Tunisia surpass their North African neighbors, securing positions within the top ten in the region. Egypt’’s success is attributed to its performance in the Government pillar (Vision, Governance and Ethics, Digital Capacity and Adaptability). At the same time, Tunisia excels in the Data & Infrastructure pillar (Maturity, Innovation Capacity, and Human Capital) (Oxford Insights, 2023).

4.1 Successful examples of AI strategy setup

Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia were among the early adopters of AI strategies, all expressing their aspirations to attain global leadership in AI. Saudi Arabia has released a preliminary edition of its forthcoming AI Ethics Principles and initiated a public consultation to gather feedback, signifying a significant step forward (Saudi Data and AI Authority, 2022). Nevertheless, in addition to focusing on ethical principles, the country’’s comparatively low rating in Data representativeness, compared to countries with similar scores suggests that the country should prioritize expanding its inclusion efforts to ensure that AI initiatives meet the needs of all service users. In the broader regional context, additional indications of progress are evident, with Jordan as an upper-middle income country from MENA having released its National AI Code of Ethics in 2022, published in English and Arabic (Government of Jordan, 2022), and ongoing efforts to develop the Egyptian Charter for Responsible AI.

Similar to Jordan, Oman has published its strategy in 2021 (MSC, 2023; Prabhu, Reference Prabhu2021). Both countries are considered as a new wave of countries where AI is not merely treated as an independent sector but is viewed as an opportunity to expedite digital development and innovation within other key sectors. In 2019, the Egyptian government established the National Council for AI to craft Egypt’’s AI strategy (The National Council of Artificial Intelligence, 2019), which has helped improve its ranking in relevant global indicators. Egypt has even introduced its National Artificial Intelligence Strategy, which includes some basic mentions of ethical considerations. Nevertheless, significant inquiries persist regarding the degree of involvement of local citizens and their subsequent implementation of these ambitious international and national regulations and strategies in real-world scenarios.

In Palestine (a war-torn MENA country), the applications address several sectors including energy (Salah et al., Reference Salah, Alsamamra and Shoqeir2022), health (Almansi et al., Reference Almansi, Shariff, Abdullah and Syed Ismail2021; Malaysha et al., Reference Malaysha, Awad and Hadrob2022), and business (Hamdan et al., Reference Hamdan, Aziguli, Zhang, Sumarliah and Usmanova2022), to cite a few. Despite the war conditions, the country succeeded in releasing its strategy in the governmental Artificial Intelligence Platform (Palestinian Government, 2021). This strategy does not appear in international reports mapping and analyzing national strategies in the region.

Across these countries, common ethical considerations include ensuring fairness, avoiding bias, protecting privacy, and establishing transparent and accountable AI systems. Each nation may tailor its approach based on cultural, legal, and societal norms. However, common challenges include the need for skilled workforce development, infrastructure enhancement, and navigating ethical considerations. Each country tailors its AI strategy to its unique economic and social context. Overall, these strategies signal a broad commitment to leveraging AI for transformative impacts on national development and technological advancement. Saudi Arabia aims to become a global leader in AI and technology by 2030, alongside Qatar and the UAE. It has opened a public consultation for feedback on its strategy draft. This is important progress. Oman and Jordan have joined a new wave of countries prioritizing AI not as an isolated sector but as a catalyst for accelerating digital development and innovation across other key areas. While the outcomes of AI strategies in the other countries, cited above, are still evolving, the establishment of these strategies represents a significant step toward their success. Table 1 illustrates a comparison between these different released strategies in the region. Only MENA countries that have established their AI strategies are included in Table 1.

Table 1. A comparative analysis of national AI strategies in the MENA

4.2 Key initiatives in launching AI ecosystem in North African countries, Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine

The North African countries within the Maghreb region, namely Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco—currently lack national AI strategies. However, each is seeing the emergence of an AI ecosystem at varying stages of development. In the absence of formal strategies, these countries are making efforts to prepare for the AI revolution. To advance common solutions across MENA and provide insights into the region’’s AI landscape in the region, the Science for Africa Foundation organized a North African convening in Cairo in September 2023 (CPHIA, 2023). This event brought together experts, policymakers, and stakeholders from Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and Libya to discuss their countries’’ readiness to implement and leverage responsible and sustainable AI, with a particular focus on health and medical applications. The discussions identified key steps needed at the national level to ensure the effective implementation of AI strategies, where they exist (CPHIA, 2023). Experts highlighted that without ethical and responsible use, data strategies and AI solutions may technically function but fail to deliver the desired outcomes. Data governance remains essential for a successful AI strategy across all applications, as it is fundamental to building trustworthy and responsible AI.

The following section will map the key players in the AI ecosystem of the Maghreb countries (Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria), as well as Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine. This will include government bodies, research institutions, startups, and civil society organizations, and will highlight the major ongoing initiatives (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020; Oxford Insights, 2020). Indeed, Libya (a war-torn MENA country) and Mauritania as Maghreb countries, as of now, do not exhibit a critical mass of actors or a sufficiently significant dynamic in the field of AI to form a viable ecosystem.

4.2.1. Tunisia

Tunisia leads in Maghreb’’s AI readiness, ranking 69th globally, 2nd in Africa, and 7th in the Arab world (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020; Oxford Insights, 2023). Since 2018, Tunisia has taken significant steps to establish an AI ecosystem. Notable initiatives include the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research’’s TASK FORCE IA in April 2018, aiming to develop a national strategy (Leaders, 2019), but facing challenges due to political instability. In April 2019, the Ministry of Industry and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises launched the AI Roadmap as part of the “Industry 4.0” strategy (GIZ, 2020), leading to impactful actions such as the Smart Industry Forum 2019 and the annual hackathon and competition AI Hack Tunisia (InstaDeep, 2019). The ministry’’s collaborations with the National School of Administration of Tunis resulted in an AI chair and a training campaign for 5000 public officials in December 2020 (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020). Several universities introduced AI in their curricula, with plans for a new engineering school focusing solely on AI. Pristini School of AI (https://www.pristiniaiuniversity.tn/fr) is the first university to specialize in AI in Tunisia and Africa. TUNBERT initiatives (https://github.com/instadeepai/tunbert) by Tunisian startups focused on natural language processing developed for the Arabic dialect spoken in Tunisia and for underrepresented languages (InstaDeep, 2021). Looking ahead, the National Council of the Order of Veterinarians is finalizing the AGRIVET SMART standards framework for AI in Agrifood and animal husbandry, providing guidelines and a structured approach for evaluation. Moreover, Tunisia has a dynamic AI startup ecosystem (Startup Tunisia, 2020), with InstaDeep as a standout success (https://www.instadeep.com/). In 2018, the Tunisian government took a significant step to foster innovation by introducing the “Startup Act” (n°2018–20), a legal framework specifically designed to benefit innovators, startups, entrepreneurs, and investors. “Startup Act” not only provides entrepreneurs with creation leave and grants but also offers startups essential tax exemptions and salary coverage, while investors enjoy tax relief (Startup Tunisia, 2020). These measures have collectively created a supportive environment that has significantly boosted AI innovation and growth in Tunisia.

4.2.2. Algeria

Mejri (Reference Mejri2020) highlighted the limited AI initiatives in Algeria. In 2019, the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research attempted to establish a “National Strategic Plan for Artificial Intelligence 2020–2030” through a workshop (CERIST, 2019). The workshop aimed to create a roadmap involving education, research, and the societal impact of AI. The Center for Advanced Technologies Development participated, presenting Algeria’’s AI research status (Centre de Développement des Technologies Avancées, 2019). Despite recommendations for a white paper to boost economic intelligence, no strategy or document has been developed. Notably, Algeria is absent from the 2020 “AI Readiness Index” global ranking (Oxford Insights, 2020). Recently, Algeria enacted Law 18–07 in 2023 to regulate personal data use and set up the National Authority for the Protection of Personal Data to ensure compliance across public and private entities (Africa Business Intelligence, 2024).

4.2.3. Morocco

The mapping of initiatives in Morocco was also mentioned in Mejri’s (Reference Mejri2020) report. Several initiatives have been undertaken in Morocco with the aim of placing AI at the forefront of public discourse and enhancing the role of research structures in the development of intelligent solutions. Morocco has undertaken impactful initiatives in AI and technology development. The UNESCO & UMP6 Initiative, originating from the Forum on Artificial Intelligence in Africa 2018, resulted in the adoption of the Benguérir Declaration, emphasizing the promotion of AI for human-centered development aligned with human rights principles (UMP6, 2018). The AL-KHAWARIZMI R&D Program launched by the government allocates a substantial budget of 50 million dirhams to encourage applied scientific research in AI and its applications (Agence de développement digital 2020). Additionally, universities and engineering schools in Morocco have launched various initiatives for human capital training in AI. The School of AI in Fes (EIDIA), established in 2019, and the “AI Movement” at UM6P in 2021 aim to position Morocco as a regional hub for impactful AI strategically, educationally, and industrially (Jeune Afrique, Reference Afrique2019). Further, the UM6P Data Center and Supercomputer Initiative in 2021, certified Tier III and Tier IV, houses the most powerful Supercomputer in Africa, solidifying Morocco’’s standing in the global Top 100 smart centers (Femmes du Maroc, 2021). The Cities of Trades and Skills Program forms the backbone of a new roadmap for vocational training, hosting an annual cohort of 34,000 trainees across multisectoral vocational platforms (Mejri, Reference Mejri2020).

4.2.4. Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine

Artificial intelligence and machine learning research are increasingly used in Lebanon in varied domains such as banks, health education (Doumat et al., Reference Doumat, Daher, Ghanem and Khater2022) and clinical applications (Mahalingam, Reference Mahalingam, Jammal, Hoteit, Ayna, Romani, Hijazi, Bou-Hamad and El Morr2023; Saab et al., Reference Saab, Saikali and Lamy2020; Azoury et al., Reference Chadi, Arz, Claude and Rob2021), sentiment analysis (Al Omari et al., Reference Al Omari, Al-Hajj, Hammami and Sabra2019), conflict (Mhanna et al., Reference Mhanna, Halloran, Zwahlen, Asaad and Brunner2023), smart cities (Natafgi et al., Reference Natafgi, Osman, Haidar and Hamandi2018) and agriculture (Htitiou et al., Reference Htitiou, Boudhar, Chehbouni and Benabdelouahab2021). Research and projects in AI governance are virtually non-existent. In Lebanon, most universities offer machine learning and AI applications courses. Besides, two universities have implemented a master’’s program in AI including an MS in Applied Artificial Intelligence (online) at the Lebanese American University (Lebanese American University, 2023) and Université Saint Joseph (Université Saint Joseph, 2023).

In Syria (a war-torn MENA country), the absence of an AI governance strategy is similar. The AI applications encompass a variety of fields including the environmental sector (Htitiou et al., Reference Htitiou, Boudhar, Chehbouni and Benabdelouahab2021), food security in war zones (Weiffen et al., Reference Weiffen, Baliki and Brück2022), and medicine (Abood, Reference Abood2022; Weiffen et al., Reference Weiffen, Baliki and Brück2022).

Given the occupation in Palestine, the war in Syria the precarious economic situation in Lebanon, and a well-known corruption background in Lebanon (Barroso Cortés and Kéchichian, Reference Barroso Cortés and Kéchichian2020; Cortés and Kairouz, Reference Cortés and Kairouz2023) and Syria (Valter, Reference Valter2018), the absence of such a strategy is understandable. Despite Palestine having published its AI strategy, the catastrophic impact and cost of Israeli occupation in Palestine led to de-development (Shikaki, Reference Shikaki2023, ESCWA, 2022, UNCTAD, 2017), making the implementation of the strategy very challenging.

5. Conclusion

The dimension of Governance and Ethics emerges as a critical aspect of AI readiness for the MENA region. Gulf states are investing heavily in technology and are the front-runner in the AI race in the region. However, most MENA middle and low-income countries do not currently have national AI strategies for several reasons including wars/conflicts issues and socio-economic and political instability. Nevertheless, an embryonic AI ecosystem is emerging, especially in the three Maghreb countries, with varying degrees of maturity. While awaiting the development of such strategies, governments have already begun launching various initiatives to prepare their countries for this new technological revolution. A key challenge for the MENA region is transitioning from academic AI concepts to practical, innovative-driven applications. To address this, fostering collaborative solutions among MENA countries could accelerate progress, with the possibility of establishing a unified AI strategy for Arab nations. This would not only enhance AI readiness but also help preserve cultural heritage, protect indigenous languages, and ensure that AI systems are trained on local data towards customized and accurate outcomes. Additionally, with the region’’s slow digitalization and adoption of AI, early investment in robust regulations and digital literacy could shape the sector’s long-term growth. Balancing these efforts with the push for technological advancement is crucial for successful AI integration.

Preparing future generations for digital skills is also critical. Governments must invest in training and reskilling programs, ensuring that both the current workforce and younger generations are equipped with the necessary digital competencies to thrive in an AI-driven world. Developing professional retraining plans will allow individuals to transition into AI and technology roles, further strengthening the region’’s capabilities.

However, a major obstacle in achieving these goals is the intense competitiveness in the AI field, which has driven high demand for skilled professionals and led to significantly higher salaries for those with the necessary expertise. This demand has contributed to a brain drain, with many AI experts in the MENA region seeking opportunities abroad. To overcome this, governments must not only focus on infrastructure and strategy but also implement policies to develop, attract, and retain AI talents. By addressing both AI adoption and the retention of skilled professionals, along with providing education and reskilling opportunities, the region can ensure sustainable progress in its AI landscape.

Furthermore, the absence of a data culture and the need to secure high-quality data by both governments and private entities across all levels in major low-income MENA countries is essential. This must be accompanied by the necessary measures for data protection through responsible and ethical use. Establishing these data practices will be a key foundation for AI development in the region, ensuring trust and promoting innovation while safeguarding privacy and integrity.

Data availability

This work is based on a report we originally submitted to the United Nations Call for Papers on Global AI Governance (https://www.un.org/techenvoy/ai-advisory-body). The insights and research contained herein are drawn from that report, and we are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the ongoing discourse on global AI governance through this extended work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amine Sghaier (Novation City, Sousse (Tunisia)) for providing resources about the recent initiatives in Tunisia and Amine Mosbeh (National Council of the Order of Veterinarians, Tunis (Tunisia)) for providing the draft of the AGRIVET SMART standards framework. Emna Harigua-Souiai acknowledges being a recipient of an ARISE grant with the financial assistance of the European Union (Grant no. DCI-PANAF/2020/ 420-028), through the African Research Initiative for Scientific Excellence (ARISE), pilot programme. ARISE is implemented by the African Academy of Sciences with support from the European Commission and the African Union Commission.

Author contribution

H. Trigui and F. Guerfali contributed to the conceptualization of the presented structure. H. Trigui wrote the original draft and collected resources with support from C. El Morr, R. Qasrawi, Jean Jacques Rousseau, E. Harigua-Souiai, E.S. Sokhn, J. Dzevela Kong and S. Znaidi. J. Dzevela Kong contributed to project administration and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing.

Funding statement

This work is funded by Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) (Grant No. 109981).

Competing interest

All authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.