1. Introduction

Perceiving his death to be drawing near, fifteenth-century landowner Robert Pilkington was determined that his legal tribulations would outlive him. Like many other men of his status in late-medieval England, he had spent half of his life going to law. One particularly heated dispute over an estate in Derbyshire had produced suits in at least nine different jurisdictions, from the manor court to the king's council, over several decades. Not long after the last of these lawsuits Pilkington committed to paper an account of all his judicial wranglings, which he directed ‘to all such as shalbe of the preve counsayle with the said Robert & his ayrs in tyme comyng’.Footnote 1 Unfolding across the surviving thirty-seven-folio book is a tale of poison, imprisonment, and intimidation in the Peak District, interwoven with mounting legal challenges and – ultimately – failures.

The value of this narrative to our understandings of law and society in late-medieval England has been well appreciated by the period's historians. In the late nineteenth century the text's first editor, the manuscript scholar William Dunn Macray, recognised immediately that it ‘sheds a considerable amount of light on the legal proceedings of the time’.Footnote 2 That potential has been capitalised upon by John Bellamy, for whom Pilkington's candid narrative revealed ‘a great deal about fifteenth-century litigation which cannot be found elsewhere, certainly not in the records of the courts’, and by Eric Ives, who felt that its insights were ‘probably unique’.Footnote 3 It has certainly gifted us with a vivid case study for the localised impact of the Wars of the Roses, for the vertical relationships shaping the rural midlands, and for the disputatious character of the period's landed gentry – these being the principal, and only, areas of scholarship in which it has hitherto featured. Yet the format and construction of Pilkington's narrative have never been fully taken into account. Nor has it been analysed as a piece of autobiographical writing, readable against a private archive and alongside a broader genre of dispute narrative.

After all, as a story of late-medieval legal exploits Robert Pilkington's is not, in fact, entirely unique. It belonged to a broader culture in which those with lands and rights to protect were familiar not only with going to law but with documenting it. Original charters and deeds, copies of judicial records, and ephemeral papers were amassed in boxes, chests, and bundles at such a rate that some scholars have talked of a ‘documentary revolution’ by the late-medieval period.Footnote 4 After collection came curation. Throughout the Middle Ages religious foundations and civic institutions in particular are known to have collated their legal paperwork into single manuscripts – custumals, cartularies, and deed books – to keep track of ancient rights.Footnote 5 A number of surviving examples frame these documents with details of the dispute that necessitated bringing them together. In other words, they were glossed with interpretation, largely to illustrate a coherent line of property ownership.Footnote 6 This format was increasingly appealing to private landowners, and especially to those among the gentry. These social climbers were preoccupied with accumulating landed estates, through marriage, purchase, and – if it came to it – ‘aggressive and uncompromising’ legal action.Footnote 7 So too were they concerned with keeping a good record of such endeavours. Urban elites of the early sixteenth century like John Lawney and George Monoux kept ledgers into which they copied deeds, sectioned according to geography and estate. Lawney's even features a first-person preface describing his work as a ‘kalendar to alle our he[i]rs’ in future efforts to protect the family estates in London and King's Lynn.Footnote 8

Although sharing the same impetus, the near-contemporaneous Pilkington narrative plainly represents a later stage in the act of interpreting the family archive. It presents a story around its documents and about pursuing claims on their evidence, written in the aftermath of litigation. Pilkington's is neither the earliest nor the only text of this nature. The production of separate manuscripts for keeping track of pleas and rulings made in various courtrooms dates back at least to the early thirteenth century, and the roll maintained by or at the order of the nobleman Warin de Munchensy to record pleadings made at various common-law courts in his suits for lands in Shropshire, Herefordshire and elsewhere.Footnote 9 An even stronger precedent is offered by the ‘roll of evidences’ compiled by one John Catesby in the last few decades of the fourteenth century. This consists of a chronological series of deeds and charters stitched atop a narrative account, in Law French, which describes Catesby's long-running efforts to secure lands in Warwickshire and the numerous barriers he faced around the deposition of 1399. Far from a neutral series of transcripts, we find here a conscious interweaving of personal recollection with regional and national turmoil.Footnote 10

As civil war scaled up and justice scaled down, the need for coherent accounting of interpersonal disputes only deepened. Going by the number of surviving examples, standalone narratives of dispute and litigation – part ‘kalendar’ of rights, part autobiographical account of injustice – seem to have been a product particularly of the fifteenth century. Aside from Pilkington's book, they are to be found within the Armburgh family roll, in the form of an effusive tirade against the family's opponents at law probably dated to the late 1430s; in the carefully evidenced account compiled by Dame Eleanor Stafford for her right to Dodford Manor in the late 1470s; and in the lesser-known memoranda of the Brome family from the very end of the fifteenth century.Footnote 11 Shared by them all was a sense that the era's political turbulence had given rise to judicial instability and, in turn, to a need to make sense of any dispute pursued throughout. This article re-examines two of these narratives and explores their function as aide-memoires of plights to secure status and as legal aids for future generations. Pilkington's book will be the primary case study, considered in conjunction with another text much like it but lesser studied: the account of Nicholas Catesby, which details increasingly desperate attempts to recapture family estates in Warwickshire through the same late-medieval legal system.Footnote 12

In the first instance, these two narratives bring into clearer focus the picture captured by the surviving legal archive: that of an expanding judicial system on the cusp of early modernity.Footnote 13 Like any case of long-running disputes waged by otherwise well-recorded litigants (usually from among the rural gentry), of the kind often subjected to careful reconstruction by historians, they describe litigation in a huge range of jurisdictions, spanning decades and generations.Footnote 14 These case studies also happen to provide rare first-person vantagepoints on significant developments in the provision of justice; and, namely, on the increasing centralisation of judicial authority under the direct supervision of the Crown. A trend towards the royal supervision of justice has been observed all over Western Europe in the centuries from 1500 onwards, but it has been seen as having especial significance in England, where the resulting conciliar (later equity) courts were central to an intensification in litigation rates by 1600 and, consequently, in the growing ‘pretensions of the state’.Footnote 15 The narratives of Pilkington and Catesby demonstrate at length why that intensification might have mattered to litigants. Yet they also highlight the many potential barriers to acquiring justice, even in novel and authoritative tribunals. That litigation did not always represent a smooth channel between state and society will hardly be news to scholars of various early modern continental contexts, who have lately contended with the many financial and logistical challenges involved in finding legal aid, in accessing courts, and in making petitions.Footnote 16 Still, the critical light that these narratives shed has the potential to challenge the lingering positivity about the early modern litigation boom within English scholarship.

Quite aside from the potential legal and political implications of this study, there are literary questions to address: why these narratives were written at all, for what purpose, and for which audiences. These are stories as much as they are legal records. They contain consciously constructed tales with clear beginnings, middles, and ends and with a penchant for colourful, even salacious detail. At their most vivid, they feature their protagonists’ voices: Robert Pilkington's denouncement from the chancel at Mellor's parish church of all attempts to ‘sewe and trowbyll me by the law’, and the insistence of Nicholas Catesby's father, Robert, before gathered arbiters that his evidence ‘be gode & true and not forged’.Footnote 17 These particulars their authors put to work within explanatory and justificatory frameworks reminiscent of supplicatory genres already common by their lifetimes, positioning themselves as victims rather than vexers at law. Glimpsable here is a different view on the interaction between storytelling and legal documentation, a field pioneered by Natalie Zemon Davis's study of the ‘narrative abilities and styles’ on display in early modern French pardon tales.Footnote 18 It is now well recognised – albeit a little begrudgingly by historians – that many records made at law contain elements of rhetorical license and even fictitiousness, whether in terms of exaggerated contents or of scribal mediation that obscures true ‘voices’.Footnote 19 Much of the recent scholarship further acknowledges the influence that memory, tropes, and law-mindedness had on statements made before court clerks and captured in pleadings. Writing for judicial institutions was influenced consciously by the individual need to have particular versions of events recorded for posterity, and subconsciously by received forms of storytelling.Footnote 20

Crucially, however, the narratives of Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby were not judicial documents. Rather, they were produced in and for much more domestic contexts. Both were written in their authors’ dying days and at junctures when their respective families were out of favour and on the brink of losing all social standing. They look back on decades of legal action to prevent that slippage, drawing from a capacious range of documents produced for and during that legal action. Once completed these manuscripts were designed to remain alongside these same family repositories. Remarkably, the relevant papers belonging to the Catesbys and Pilkingtons still survive, in transcript and in separate archives. They offer a new perspective on the narratives, offering not only an opportunity for tallying up their untruths but also for discerning the choices made in their structuring and argument, too. Those choices mattered because both narratives looked to the immediate future, and specifically to adult heirs expected to take up their fathers’ struggles. What they received was a record of their forebears’ ‘continual claim’ to certain lands, executed through near-constant disputing and litigation. One implication is that the relationship between law and literature went both ways. It was not only that received rules for plot and structure shaped legal documents. The complex and exhausting process of litigation, and the documentary formulae it involved, engendered its own form of storytelling, too.

After introducing the two narratives under consideration this article situates them in the lifecycles of the litigation they recount and the men who wrote them. Initially, analysis attends to the trajectories of disputing laid out here, with cases waged all the way from the manor to the monarch. Scrutiny then turns to how, when, and why these manuscripts were created. The two case-study texts are recontextualised within a proposed oeuvre of first-person litigation narratives among members of the late-medieval English gentry, which share impulses. Together they suggest that even for the greatest beneficiaries of the early modern ‘legal revolution’ litigation was not a reflexive or dispassionate exercise. Our protagonists were emotionally invested, enough to envisage reckoning with law beyond their own lifetimes. That they did so has consequences for the ongoing scrutiny of the very concept of ‘lawmindedness’, particularly in terms of where it might have manifested itself – both within and outside of the courtroom.

2. The narratives of Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby

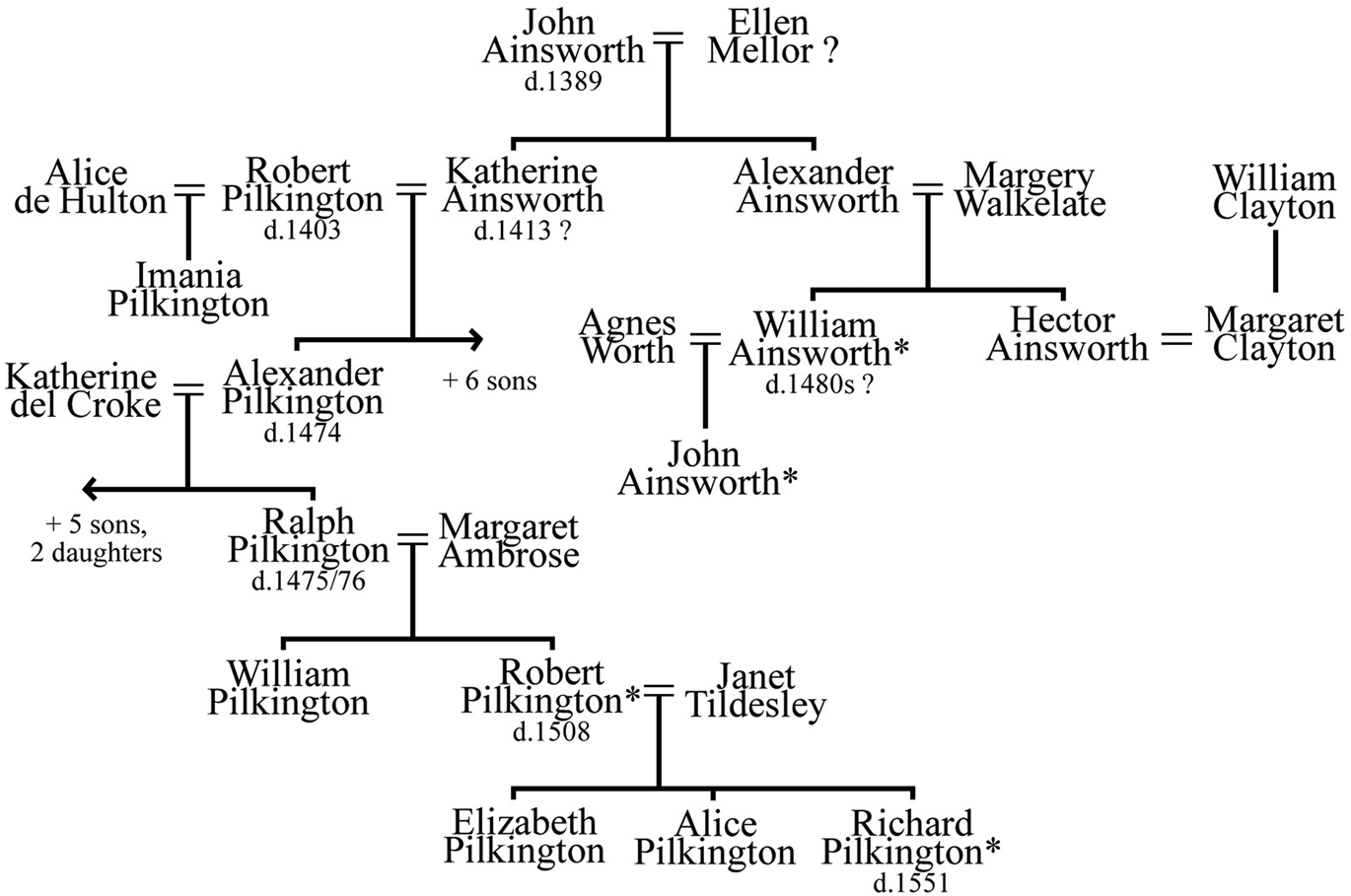

Of the two manuscripts examined here, the better known is ‘The Narrative of Robert Pilkington’, otherwise called ‘The tytll of Pylkynton to Ainesworth landes’. The Pilkingtons were an ancient Lancashire dynasty whose main line had risen to knighthood through military service and parliamentary membership under the Plantagenet kings.Footnote 21 The author of the ‘Narrative’ belonged to a junior branch settled in the moorland manor of Rivington, near Bolton. While his autobiographical account was a product of the very early sixteenth century the dispute at its centre reached all the way back to 1383, when this Robert's great-grandfather, another Robert Pilkington, married Katherine Ainsworth, a daughter of John and Ellen Ainsworth. The Ainsworths hailed from a patronymic town just five miles or so north-west of the township of Pilkington, in Lancashire. Through an earlier marriage they had acquired lands in Mellor in Derbyshire (now Cheshire), too.Footnote 22 The union between Robert Pilkington and Katherine Ainsworth had brought the Mellor estate to their heirs, including their great-grandson, the Robert Pilkington of the ‘Narrative’. Unfortunately, he was not the only interested party. Peace in Mellor was soon disrupted by the emergence of William Ainsworth, an illegitimate son of Alexander Ainsworth, who was the brother of the aforementioned Katherine (see Figure 1). This William and his son, John Ainsworth, would vex the Pilkingtons and their tenants in Mellor for decades thereafter.

Figure 1. Family tree of the Pilkingtons and Ainsworths, fourteenth – sixteenth centuries (asterisked names are protagonists of Robert Pilkington's ‘Narrative’: North Yorkshire Record Office ZDV X 1).

A small town in the remote Dark Peak, Mellor hardly seems a likely subject for such a feud. While southern Derbyshire was dominated by lucrative lead mining, battles in the northern parts were waged through the to-and-fro of cattle between rural pounds.Footnote 23 Such affrays affected not only the lives of the Peak's tenantry but also the smooth running of royal governance. The manor to which Mellor's townsfolk owed fealty, the High Peak, was part of the Crown's Duchy of Lancaster, from whom the Pilkingtons claimed to hold their estate.Footnote 24 The disputed properties encompassed some eight messuages with sixty acres of land, twelve acres of meadow, six acres of pasture, and a dozen acres of lucrative woodland, sustaining at least seven tenants and their mill.Footnote 25 This represented enough of a regional foothold to attract the attention of the influential Savage family, who could count among their number various officials of the Duchy as well as one of Henry VII's most senior councillors and who threw their weight behind the Ainsworths at every turn.Footnote 26

Notwithstanding this significant disadvantage, Robert Pilkington doggedly pursued litigation from at least the late 1470s, when in his twenties and newly lord of the family estates, through to c.1501. The narrative, produced between that terminal case and Robert's death in 1508, offered ‘a substanchall recorde’ of the ‘mone grete chargys and costes’ lost through these suits. It is written largely in a single erratic hand – probably Robert Pilkington's own – excepting a few passages at the very end added by his son, Richard, which summarised plans for further suits at the central common-law courts in 1511.Footnote 27 The complete quarto-sized booklet is held now at the North Yorkshire Archives, having come there by way of Newburgh Abbey and the collections of the Belasyse and Wombwell families – descendants of the Pilkingtons in Yorkshire.Footnote 28

The second, lesser-known text examined here is the ‘Account of a Catesby Lawsuit’, which takes the form of a roll of parchment membranes stitched together in Chancery style containing a narrative of some 13,000 words.Footnote 29 Although different in format, much like the Pilkington book this manuscript has been taken to epitomise the efforts of the fifteenth-century rural gentry to accumulate and protect landed estates through marriage and service to the region's magnates, against the backdrop of the tumult and opportunism generated by the Wars of the Roses.Footnote 30 Among late medieval English historians it is best known for its incidental identification of one John Eborall as the priest who conducted the secret marriage between Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville.Footnote 31 The text is long overdue a fuller analysis.

This narrative has two identifiable protagonists: Nicholas Catesby (died c.1502), its author, and his father, Robert Catesby (d. 1467), whose recollections come to us second-hand. They belonged to an ancient affinity which had spent the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries acquiring estates in Warwickshire and Northamptonshire, establishing themselves within the guilds of Warwick and Coventry, and entering the ranks of parliament and the inns of court.Footnote 32 Robert and Nicholas were direct descendants of the aforementioned ‘man of law’ John Catesby, known to historians for his own prolonged efforts in the fourteenth century to obtain estates in Ladbroke, close to the Northamptonshire border, through suits at assize sessions, private arbitrations, and petitions to the Crown – all accounted for in his narrative roll.Footnote 33 By Robert Catesby's day, in the fifteenth century, this line of the family retained links to ‘peripheral’ Warwickshire manors of Hopsford and Bubbenhall while also building a new base in Newnham, Northamptonshire.Footnote 34 His son Nicholas Catesby is also recorded as having been admitted to the Inner Temple by 1490, for training in the common law, and appears to have resided in London when not in the midlands.Footnote 35 Both men benefitted from close connections to their more prominent paternal cousins, Sir William Catesby (III) and his son, William Catesby (IV), the notorious ‘cat’ of Richard III's inner circle.

The dispute covered in Nicholas Catesby's narrative hinged upon the dying wishes of another substantial Warwickshire landowner and lawyer, Nicholas Metley, who had died without male heirs at the ‘New Temple’ in 1437.Footnote 36 On his deathbed, this Nicholas Metley had named as executors his mother Margaret, his wife Joan, and Robert Catesby. While Metley's manors of Wolston and Merston were to be left to his daughter, another Margaret, his home manor of Baddesley Clinton and moieties in Wappenbury and in ‘Ulsthorpe’ (probably Ullesthorpe, Leicestershire) were to be sold to purchase prayers for his soul.Footnote 37 It was these last two parcels that came to issue between the families.

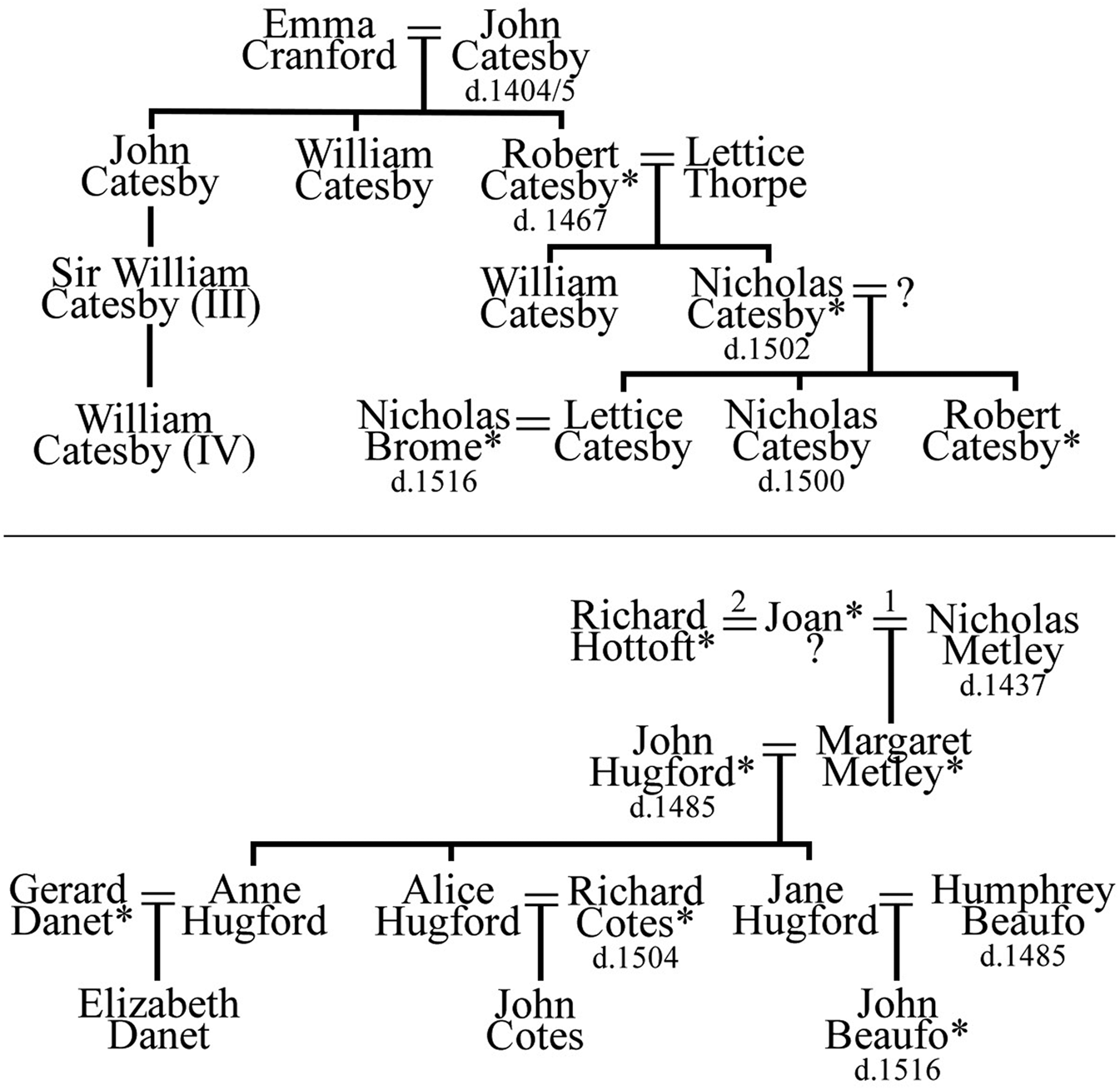

Catesby claimed to have purchased the estates from the Metley women after their ‘frendes and wellwillers’ had ‘avysed and counselled them to make … hasty sale’ in order to avoid any forfeits and obligations.Footnote 38 Yet uncertainty over whether he had the right to do so as an executor meant that within just a few years a challenge to Ullesthorpe was posed by Metley's widow, Joan. She had by then re-married, to Richard Hottoft – a ‘grette doer’ in Leicestershire and servant to ‘the mighty Duke of Bukks’ (Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham).Footnote 39 A generation further on, the claim to Wappenbury was taken up by the daughter of Joan and Nicholas Metley, Margaret, and her husband, John Hugford. The Hugfords possessed lands in Warwickshire, and they too were said to ‘bare gret rule in the[ir] shire’.Footnote 40 Later, in the 1490s, further suits for the entire estate pitted Nicholas Catesby against the sons-in-law of John and Margaret Hugford: namely Gerard Danet, husband of Anne Hugford, and Richard Cotes, married to Alice Hugford. These men were joined in litigation by Nicholas Brome of Baddesley Clinton, guardian to John Beaufo, the infant son of Jane Hugford and great-grandson of Nicholas Metley (see Figure 2).Footnote 41 Christine Carpenter's study of the Warwickshire gentry identified the Catesbys, Metleys, Hugfords, and Bromes as astute land managers and significant social climbers – little wonder, then, that they rubbed shoulders here.Footnote 42

Figure 2. Family trees of the Catesby and Metley families, fifteenth – sixteenth centuries (asterisked names are principal disputants in Nicholas Catesby's ‘Account’: The National Archives E 163/29/11).

The result was feuding and litigation beginning in the 1440s and continuing to the very end of the fifteenth century. At the tail end of these lawsuits and on the eve of his death in c.1503, Nicholas Catesby filled seventeen membranes with his own remembrances and copies of the relevant legal documents from those past sixty years.Footnote 43 This included the full text of certain petitions and even of orders taken from ‘the boke of entrie of ples … kept in the … Sterre Chambre’, presumably meaning the now long-lost registers of the court of Star Chamber.Footnote 44 In between, Catesby provided a narrative account of how the dispute had unfolded and escalated since Metley's death, in his own and his father's lifetimes. This appears a more piecemeal production than Pilkington's book; some membranes are sewn over the bottom of others, replacing and editing the text beneath. The complete roll now survives in The National Archives, within an artificial subseries of the Exchequer collection known as the ‘Catesby papers’. It is difficult to pin down with any certainty the roll's route to the central archive, aside from speculating that it was once among the material confiscated by the Crown from the broader family's Northamptonshire base when one of its descendants was attainted as a Gunpowder Plot conspirator in 1605.Footnote 45

There is scarcely enough space here to reconstruct the trajectories of both disputes and their many renderings into litigation, carried by several generations through at least thirteen jurisdictions. Nor is such re-telling the purpose of the analysis that follows. Rather, the aim is to identify the impulses shaping this form of life-writing (or law-writing), and to reflect on how this might deepen our understanding of law-mindedness in this period and beyond. An immediate influence was the broader archival contexts to which both narratives once belonged. Robert Pilkington's book must have originally resided among the collection of deeds and charters for his family's estates which remained in situ at their manor house in Rivington long after it had passed to new owners. In 1661, extracts from those documents were copied by the antiquarian Christopher Towneley, thus preserving material against which Robert Pilkington's version of events can be compared for the first time.Footnote 46 Likewise, supplementary paperwork survives to corroborate (or not) the account of Nicholas Catesby, including further litigation records within The National Archives and various deeds and memoranda in repositories closer to his family's homelands – in Birmingham, Northamptonshire, and Warwickshire – having been passed down through descendants.Footnote 47 These documents shed light on the larger extent of the Catesbys’ property wranglings, of which the row over the Metley estates formed just one strand. Drawing links between the evidence of the narratives and their authors’ other archival traces reveals both to have involved more complex disputes than such first-person, one-sided remembrances let on. We are therefore forced to examine how and why such carefully framed versions of events could emerge – not for the audience of the courtroom, where we have come to expect such creative and rhetorical expression, but in the more intimate space of the family archive. Before that, we must unpick the nature of these retellings.

3. Telling tales of litigation

In the fifteenth century as today, a good story required certain elements: a comprehendible narrative structure, recognisable plot points, and a persuasive message. The challenge for both Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby was to give meaning to a series of events which were properly set in motion long before their own lifetimes. Pilkington looked all the way back to the 1380s, and Catesby to the more recent past, in the 1430s. In the broadest sense, explaining what happened in the years up to the early sixteenth century involved recourse to shared ‘historical time’.Footnote 48 The period's frequent turnover in monarchs, and particularly the arrival first of Richard III and then Henry VII in quick succession, offered the clearest tidemarks against which both authors marked their ebbing fortunes. For example, Nicholas Catesby stressed that his family's prospects had plummeted in the aftermath of the Battle of Towton in 1461, where they had supported Henry VI while their opponents had backed the Earl of Warwick. When ‘kynge Herry lost the feld’, the Catesbys were forced into exile in Scotland, and the victorious Hugfords took advantage of the chaos to seize the Wappenbury and Ullesthorpe estates.Footnote 49 Robert Pilkington's plight was similarly aligned with moments of ‘grete trowbull in ye land’, for example when the ‘comyns in Deyneshyr & Cornewall arose in grete ostes agaynys ye kyng’ in 1497 and halted all legal processes.Footnote 50 These references aside, however, both disputes gained greater momentum from much more intimate circumstances. It was the cycle of marriages, births, and deaths within their respective networks which muddled affairs, raised new emotions, and elicited fresh lawsuits. The personal and the political offered parallel points of reference against which these writers framed their stories.

Of course, part of the personal framework for both narratives were the real legal issues in dispute. As Nicholas Catesby described it, the claims against his hold on Wappenbury and its associated estates had to do with technicalities around testamentary executions. Early on, it was doubted that Robert Catesby really had been named an executor to Nicholas Metley at all, and witnesses at Metley's deathbed were asked to confirm that his dying wishes had been written down as a formal will and testament.Footnote 51 There was also the conundrum of whether co-executors could sell lands to one another, or whether an individual executor could ‘be both seller & byer’.Footnote 52 This had even greater significance by the end of the fifteenth century, with questions surrounding the proper remit of testamentary executors only recently hashed out by canon-law theorists.Footnote 53 The question was still being posed to Nicholas Catesby before Star Chamber in the late 1490s. Robert Pilkington's dispute, meanwhile, stemmed from the persistent problem of competing documentary proofs. The Ainsworth claim to Mellor allegedly rested on an old deed by which Alexander Ainsworth had enfeoffed lands there in fee to his neighbour, the vicar of Glossop. They were to be released to the Pilkington line only in the event that Alexander's illegitimate sons, William and Hector, produced no heirs. Incidentally, an indenture with very similar terms can be found among those documents copied out of the Pilkington family archive at Rivington. Although its date is unknown, it duly records an agreement between the same Alexander Ainsworth and one William Clayton – no vicar, but the father of Hector Ainsworth's wife, Margaret – to grant the reversion of Mellor first to Hector and then to William Ainsworth (see Figure 1).Footnote 54 Regardless, the Pilkingtons spent the fifteenth century claiming this deed to be a forgery, with the added subtext that bastard heirs had no official right to inherit land anyway. The various arbiters and judges before whom this matter was presented over the years were asked to determine the validity of the original document and how far it might override gifts of the estate made to the Pilkington line in the 1380s.

Both narratives returned to determined legal parameters, especially when describing courtroom scenes down the years. Yet these technicalities were otherwise subsumed within emotive stories of inter- and intra-familial relationships – and their eventual breakdowns. Hence Robert Pilkington appealed as much to the conventions of natural kinship as to any documentary foibles by insisting that the late Ainsworths would never have preferred the line begotten by Alexander Ainsworth and his ‘lemmon’ (paramour), a woman called Margery Walkelate, over their ‘doȝter & … right heyr’, Katherine.Footnote 55 Likewise, while Nicholas Catesby's narrative opens with a detailed description of the discussions around Nicholas Metley's deathbed in 1437, it proceeds rapidly into a description of numerous violent dispossessions that unsettled the Catesbys’ social networks in Warwickshire. Documents in local archives tell us that Robert Catesby and Joan Metley, Nicholas Metley's widow, had initially cooperated in managing her remaining lands in the region, for example in jointly receiving rents from Baddesley in the year after her late husband's death.Footnote 56 Yet by the time that Nicholas Catesby wrote his account, just over sixty years later, Joan was remembered as a ‘styborn and a gret herted woman’ who, along with her second husband, had ‘manassed & thret’ various feoffees against making any estate to Robert Catesby before entering the properties at Ullesthorpe herself. The general bad faith of all identified opponents was a key device of both stories, as it was (unsurprisingly) in most accusations made at law. Robert Pilkington was effusive about the ‘yll wyll’, ‘malise’, and ‘vengefull dealing’ of his Derbyshire enemies. This was in contrast to his own good faith: for example, in agreeing to pay an Ainsworth widow a mark in dower purely ‘of Þi free wyll … [though] narther lond nor howse [was] assyngnyd [to her] in Mellur’.Footnote 57 Nicholas Catesby similarly insisted that he had always ‘lovyngly’ offered his opponents numerous opportunities to resolve their dispute through judicial intervention.Footnote 58

So all-consuming were these enmities that it sometimes appears as though it was their course that these narratives were designed to track. The explanation of the Pilkington-Ainsworth history forming a brief preamble, Robert Pilkington's story properly opens on an episode in 1478 when he had been arrested at the behest of Sir John Savage (III) and imprisoned at Macclesfield gaol, an action for which he did not perceive (or, at least, report) any just cause. While languishing there, the troublesome William Ainsworth delivered him ‘a mes[s] of grene pottage … which hade poison put in’, and he was saved from death only by Sir John's offer of ‘grete curys’, at a cost. Like Nicholas Catesby, Pilkington opted for drama over detail. The deftness in using this as the establishing vignette is made all the more clear in light of evidence that this was not, in reality, the beginning of the Mellor dispute. A surviving indenture in the Rivington archive made at the time of his marriage to Janet Tildesley in 1476 – two years before Pilkington's alleged arrest – explicitly excluded from the couple's inheritance those lands ‘now in debate between Robert [Pilkington] and William Aynesworth in Mellor’.Footnote 59 The dispute was possibly live a generation earlier, when Alexander Pilkington (Robert's father) had been questioned on his deathbed as to whether he had ‘ever made any bargaine annuete [or] gift of any lands and tenements … in Mellur’, to which he answered that he had done so only ‘onto the right heires of his body’.Footnote 60 In his retelling Robert Pilkington makes no reference to any such pre-existing conflict, legal or otherwise, between himself and William Ainsworth.

That is because the Ainsworths appear, ultimately, as side characters in the retelling. It is no coincidence that the first attempt at dispute-resolution described in Robert Pilkington's account is a hearing at Macclesfield undertaken immediately upon his release from imprisonment, where Sir John Savage (III) ‘calde ye lond & all the mater his & not [William] Aynesworthes’. Although Pilkington himself claims that his book was written ‘To avoid the title of John Aynesworth son of William Aynesworth bastard’ and to be a ‘substanchall forbarr agaynys John Aynesworth’, we hear very little from either of these opponents in the course of the text.Footnote 61 They rarely seem to have attended on suits advanced in their names, and their interests were apparently subsumed under those of the Savages at every turn. Pilkington's choice of chronological framing, beginning with the formal entry of the Savages into the dispute (and ending with an extensive confrontation with the royal councillor Thomas Savage), served to emphasise this greater contest. Pilkington was at pains to stress where it ended up: by the 1490s, after years of forcible entries, riots, and denouncements in the parish church, Pilkington reportedly lived under threat that he ‘schuld have such a breykefast in Mellur as he nor non that durst take his part schuld be abull to escape away [a]lyve’.Footnote 62 As both of these narrators implied, legal ambiguities could be easily exploited by people with stronger connections and greater resources.

As they proceed to describe efforts to relieve their respective conflicts, the two narratives emphasise the ‘inseparability of private power and public influence’ within dispute-resolution in this period.Footnote 63 Initial attempts to find a peaceful solution typically involved the informal mediation of nominated third parties – usually friends and neighbours – and so the need for trustworthy advisors started early.Footnote 64 An episode in Nicholas Catesby's account neatly captures the ethos of such private negotiations. In 1485, presumably exhausted from twenty-five years of litigation against the Catesbys, an ailing John Hugford invoked the assistance of one John Spenser, of the rising wool-trading family based at Hodnell, who just so happened to have ‘ben acqueynted with the seid Nich Catesby of Chyldehode’. Like other mediators before him, Spenser's job was to convince Nicholas ‘with many gode & kynde wordes’ to ‘be agreable to a tretys and a lovyng ende’, and to agree to an exchange of lands – Ullesthorpe for the rich woodlands of Wappenbury. This might have worked, had Hugford not died before negotiations could be concluded.Footnote 65

While both narratives tell of regular recourse to the opinions of friends (even once formal litigation had commenced, importantly), they are perhaps most striking for their evocation of ‘vertical ties’ as an ordering force.Footnote 66 To even his odds against the Ainsworths and Savages, Robert Pilkington called on the support of Thomas Stanley, Earl of Derby, and his son George, Baron Strange. The Stanleys were granted lands forfeited by the senior line of Pilkingtons in 1489, including the manor of Pilkington, so it made sense to stay in their good books; by 1495, Robert was a servant of the Earl, who was by then stepfather to Henry VII.Footnote 67 Earlier in the century, Robert Catesby had moved much more quickly to seek out regional magnates. His own affinity with the Ferrers of Groby having apparently made little impact on his prospects, he turned instead to the Duke of Buckingham, whom he petitioned with the request to rein in the activities of his servant, Richard Hottoft.Footnote 68 The duke proved amenable to Catesby's claims, agreeing that he had been ‘mysentreted in the premisses’ and commanding the appointment of arbiters for hearings to be held in Lutterworth, Rugby, and Leicester. When that failed to stick, the duke licensed Robert Catesby to arraign an assize of novel disseisin (an action to recover lands of which a plaintiff had been recently dispossessed).Footnote 69 Here as elsewhere, the influence of the magnate proved to be a feature of, rather than an alternative to, suits at law. Crucial to both stories was the implication that even this kind of public regional power had not been enough to overawe their opponents.

This meant entering into formal litigation – suing out a writ, entering information, or submitting a petition to legal authorities – and hoping to disprove the contemporary proverb that ‘better is a friend in court than a peny [in the] purse’.Footnote 70 Since land disputes were so often waged on the ground, through forcible entries and distraint of goods, they typically required recourse in the first instance to local and regional courts, at the manorial or the county level. Reflecting on these efforts later, Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby certainly felt they had been subject to the whims of local officials, who had their own vertical relationships to maintain. In April 1494, Robert Pilkington and his Mellor tenants turned to the sheriff of Derbyshire (possibly Nicholas Kniveton) to execute a writ for the release of cattle lately impounded by John Ainsworth at the castle of the High Peak. Yet the sheriff was so ‘grevyd towardes the said Robert [Pilkington]’, especially for calling on higher authorities when he had failed to process the writ quickly enough, that he demanded ‘larg[e] money’ for his compliance in the matter.Footnote 71 Later that same year, the efforts of two tenants to enter writs of replevin (commencing procedure to recover seized chattels) at the county court in Derby against John Ainsworth for the return of cattle kept at Chapel-en-le-Frith were stymied when the court's bailiff simply failed to show up. They were saved their time and money only when another official, Robert Bradshaw, received them and admitted their attorneys ‘of his awne mynde & kyndnes’.Footnote 72 The presence of other Bradshaws in the Pilkington ‘Narrative’ suggests that Robert might have had more favour with this family.Footnote 73 It also indicates that he was better connected in Derbyshire than he was otherwise willing to let on. For Pilkington as for Catesby, stories of misfortune and injustice were heightened by lending credence to the notion that local judicial processes were unsurpassable.

By emphasising corruption in localised law courts these two narrators were likely drawing not just from age-old aphorisms but also from political discourses of their own day. Both identified oppression in one setting in particular: special assize sessions, sued out of the royal common-law courts but convened at nearby administrative centres, with juries appointed from the area and therefore notoriously susceptible to overlapping influences of kin and patrons. Nicholas Catesby claimed that his father had suffered from sinister machinations at a novel disseisin assize at Leicester in the early 1440s. The jury there initially defaulted for fear of Richard Hottoft and his master, the Duke of Buckingham, and eventually quibbled that Robert Catesby might have recovery of Ullesthorpe only against Nicholas Metley's daughter, Margaret, and not against her mother and stepfather. This judgment would later be questioned by subsequent Metley descendants on the grounds that Margaret had been ‘within age’ at the time.Footnote 74 Elsewhere, the entire back half of Pilkington's ‘Narrative’ is dominated by the events and the fallout of what he called a ‘partial panel’ held at Derby in July 1498, supposedly ‘knawen and provyd for the most parchall whest [inquest] that eyver passyd at Derby that ane mon couth thynke or herde tell’. There, Thomas Savage – the royal councillor and Bishop of London, son of one Sir John Savage (III) and brother to another (IV) – was alleged to have packed the jury with ‘boundmen to the Savages … olde househad servaundes [and] free tenaundes retaynyd by fee or lyverey’. Meanwhile one of his brothers, James Savage, stood at the bar for Ainsworth. Acquiring Mellor had clearly become a family affair.

The subtext here is that such behaviour was not only immoral but also, potentially, illegal. Pilkington's references to the influence of retained supporters was likely no accident, since by the 1490s the abuse of livery-wearing – of sizeable bands of ‘retainers’ wearing a lord's badge – was under scrutiny by both Crown and Commons, particularly in the context of the judicial system.Footnote 75 Hence Pilkington's story deliberately underlined just how easily a packed jury could overturn what should (he claimed) have been a straightforward decision in his favour. The jury at the 1498 assize was called ‘owte of ye counsayle house’ several times by the judges, he claimed, to be reminded that John Ainsworth's evidence for an alleged recovery of the Mellor estates ‘stode to non affeckyt’ and that Pilkington had long received an annuity from the same lands. They were ordered that they should ‘fynde authere all or non dew’ to either party. In other words, Robert Pilkington's title was good. Yet, in the end, the jurymen ‘wer all aggreyet that ye said Robert hade disceysyd [disseised] ye said John’ and they formally allowed John Ainsworth to recover all the lands in Mellor. This was a ruling so flagrant that it apparently caused ‘a grete clamor … amonges all ye courte all ye town of Derby & all ye countre’.Footnote 76 Complaints from the countryside about the problems plaguing assize juries had already reached Westminster by the time of Pilkington's tribulations. Although not targeting liveries specifically (which was not, and arguably could not be, made illegal), the parliament of 1495 passed two acts offering aggrieved defendants a formal channel to try partial panels at the central courts, and potentially to nullify their judgment.Footnote 77 It was on the basis of one such ‘newe acte’ that Pilkington pursued a suit in King's Bench towards the end of that decade.Footnote 78 Just as Nicholas Catesby touched upon the latest canon-law thinking on executorships, Pilkington was plainly up to date with common law provisions.

It was not only the latest legislation that served both men's causes and shaped their subsequent stories. They also benefitted from the Crown's increasing willingness across the later fifteenth century to be drawn into interpersonal disputes, especially in cases where lower courts and legal authorities had failed to offer resolution. The means for doing so were, at first, relatively informal. So, in the mid-1460s Robert Catesby fortuitously met John Eborall, parson of Paulerspury, who happened to have recently married Edward IV to Elizabeth Woodville. Having heard ‘mone of the great iniurie don’ to Robert, Eborall agreed to convey a petition to Queen Elizabeth, her mother the Duchess of Bedford, and her brother Lord Rivers. Their support would have outweighed the authority of John Hugford's master, the Earl of Warwick, had the queen not ‘answerd … that if hir grace enterprised that mater hit myght cause a gruge bytwen hir & the seid Erle’.Footnote 79 Robert's son Nicholas duly copied this unsuccessful bill into his narrative roll, followed by several petitions that he had later submitted to successive kings who offered their own, ostensibly impartial, routes to redress. When the newly crowned Richard III ‘made a p[ro]clamacion gen[er]all that ev[er]y man wronged that wolde co[m]pleyn shuld have hasty remedye and gode no man except[ed]’, Nicholas quickly presented a bill against Hugford during that king's progress to Warwick, in August 1483.Footnote 80 That he took the time to expound in his account upon the virtues of the first Tudor king, whose arrival was ‘blessed b[y] godde’ and ‘to the gret comfort … of many other whech long hadde suffred gret wronge’ suggests that Nicholas Catesby, at least, bought into contemporary expectations about the king as the ultimate justice-giver.Footnote 81

He and Robert Pilkington acted on that belief too, by taking advantage of institutional developments under the early Tudors that provided more routine access to the king's remedies. In 1485, Nicholas Catesby petitioned the recently crowned Henry VII to complain of the ‘p[ar]cialitie of yor Shyreve of yor seid shires [of Warwickshire and Leicestershire]’ which had barred him from justice up to that point. A note entered beneath this copied bill in Catesby's roll indicates that Henry VII duly issued a writ under his privy seal summoning Nicholas Brome, Gerard Danet, and Richard Cotes – who had, allegedly, seized lands from Nicholas Catesby – to appear before ‘oure counsell … whersoev[er] it shall nowe happen us to be’. A series of pleadings then followed, conducted with the oversight of the Lord Chancellor in the court of Star Chamber.Footnote 82 This was the branch of the council administering justice in situ at Westminster; another branch, later known as the court of Requests, remained with the king and his entourage as they travelled around the realm. It was this latter, itinerant tribunal that Robert Pilkington encountered as a defendant in 1493, having been summoned to answer to the case brought against him by John Ainsworth at Kenilworth and Collyweston.Footnote 83 Both narratives therefore chart the crystallisation of royal justice by the dawn of the sixteenth century, and the linear movement of their respective cases into these upper jurisdictions. Indeed, this shared terminus for both cases might also explain why their subsequent narrative retellings bear so much resemblance in language and form to the English supplications of this conciliar (later ‘equity’) jurisdiction – to the emotive bills submitted to the court of Chancery, for example.Footnote 84

Where these narratives break from the deferential convention of petitions is in depicting the shortfalls of this most powerful of jurisdictions. In Star Chamber, Nicholas Catesby's opponents raised an exception to his bill of complaint, griping that it ‘comprehended not a sufficient title’ and requiring him to submit another, more detailed petition for the Michaelmas law term in autumn 1497. By that time, Nicholas was so ‘weried & empoverysshed … that he is not nowe hable to pursue the comen lawe nor els wher for his forseid enheritaunce’, claiming to be ‘a pore gentilman & the porer for beyng out of possession of the seid landes and ten[emen]tes’.Footnote 85 His roll ends on a series of Latin entries, seemingly copied from Star Chamber's order books, recording the appointment of commissions to hear the matter through to the Trinity term in summer 1499. No conclusion is recorded in the roll – the procedural notes simply tail off – and with the original registers now lost it is impossible to know if a decree was ever passed before Nicholas Catesby's death a few years later. We might glean the outcome from other sources, however. Appraisals made of Catesby's landholdings in an unrelated debt suit in 1500 reported nothing of Wappenbury alongside his other lands in Knightlow Hundred.Footnote 86 Later on, a grant made in 1512 by John Beaufo, great-grandson of Nicholas Metley, gave a third part of Wappenbury manor and the moiety of Ullesthorpe to his cousin, John Cotes, son of Alice Hugford and the aforementioned Richard Cotes (see Figure 2).Footnote 87 In short, the Warwickshire estates were at some stage carved up precisely as the Catesbys’ opponents had demanded: equally between the descendants of Nicholas Metley.

Elsewhere, Robert Pilkington's defence before Henry VII's itinerant council quickly foundered. At one hearing in 1493, the councillors accepted that Pilkington had the right to Mellor by ‘lyne of blode and discent’ and that Ainsworth's deeds ‘were enturlyned’ and so not lawful evidence.Footnote 88 Yet, despite Thomas Savage's promise that he ‘schuld not mayntene ye said John Aynesworth nerther be awe nor law’, he continued to do so throughout the rest of the decade. After trying and failing to submit a counter-petition to this council, which was by that time headed by Savage as president, Pilkington turned to King's Bench. There his error case against the 1498 panel continued through several terms and into Hillary 1501, when business abruptly stopped. As the original record has it, ‘the court … [was] not here yet’; Pilkington's narrative reports that it was unoccupied for a year or so following a plague outbreak.Footnote 89 The case lapsed, and Pilkington died in 1508 seemingly having never reclaimed the estate in Mellor. Neither of the two inquisitions post mortem on his possessions, the first at Lancaster in March 1509 and the second at Preston in April 1511, record any lands aside from those in Rivington, and one returned that Robert Pilkington held no other estates from the Duchy.Footnote 90

Mellor was presumably left out of these inquisitions because it had remained unreclaimed on Pilkington's death. After all, around the time of the second inquest his son Richard Pilkington took up suit against John Ainsworth, by then said to be ‘sore diseassett’ and likely to die, under a writ of scire facias – a process which demanded clarification (literally, for it to be ‘made known’) why an existing matter of record ought not to be overturned. This was designed to open up the assize of 1498 for scrutiny once again, but the matter was pleaded without resolution in King's Bench until spring 1516.Footnote 91 He may have achieved more success outside of the courtroom, however. Among the surviving Rivington deed transcripts there is one recording that Hector Ainsworth, the elder of Alexander Ainsworth's illegitimate sons, had granted all the lands and tenements in Mellor settled upon him by his late father to this same Richard Pilkington.Footnote 92 When, exactly, this agreement was made is unclear. Hector must have lived a very long life for it to have occurred in the early sixteenth century. Still, whatever validity this transaction might have had, neither the Pilkingtons nor the Ainsworths can be connected directly with Mellor again after the early sixteenth century.Footnote 93

All of this was to come later, however. Within their own lifetimes all Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby had within their power was to provide snapshots of how they had left their affairs. Their manuscripts are carefully constructed stories rather than neutral evidences. Both men structured the retellings of their own and their ancestors’ disputing around identified enemies and mounting episodes of injustice, from the initial fall-out (whenever that was said to have occurred) to final failed lawsuits. It is ultimately no coincidence they tell of disappointment in all facets of dispute-resolution – formal and informal, local and central, old and new. They drew much of their exposition from medieval commonplaces about the challenges of going to law, and from more contemporary discourses about how those imbalances ought to be mitigated. The result in both cases is tales which are at once timely and timeless, retrospective and of their moment.

4. Making records of ‘continual claim’

We move now from the general to the personal; to the place of Pilkington and Catesby's narrative-writing within their lifespans, to their impulses for writing, and to afterlives and audiences of their texts. Primarily, these texts must be explored as interpretive tools for broader family archives. Undertaking a comparison between the narratives and their evidences in fuller detail further demonstrates how these writers intended to provide coherence to complex events, by simplifying the course of litigation and even by omitting information that would undermine their tales of injustice. Secondly, these two examples will now be examined in the same frame as other contemporaneous dispute narratives: those by the Armburghs, Staffords, Bromes, and even by other Catesbys. Taken together, these manuscripts capture the accumulation of lawsuits, documents, and grudges, in an emerging form of autobiographical writing about law. Through borrowed supplicatory rhetoric they also turned long-held quarrels into something useful. The continuity of disputing and litigating, no matter the changing players, the political chaos, and the shifting judicial landscape, was their key message. They looked to influence the future as much as to recount the past.

Part of the influence these writers hoped to impart was the extent of their personal investments in their respective claims. So emotionally committed were they to their pursuits that both their narratives ultimately substantiate characterisations of the late-medieval gentry as unwilling to lose out in any dispute with their equals, even from beyond the grave. Nicholas Catesby himself reportedly declared at one arbitration meeting that ‘[ei]ther he hadde right to alle or to no thing’ and so ‘he wolde never rel[ease] his right or any parte yerof for in space commeth grace’ – in other words, he would never give up any part of his right.Footnote 94 Both he and Robert Pilkington also routed substantial financial resources into their suits – spending, it seems, far more on litigation than their disputed lands were actually worth. At the war-time aid assessments of 1497, Pilkington's estate in Mellor was estimated to yield a handsome 40 shillings a year, twice the liability threshold, seeing him pay a substantial 9 shillings and 6 pence in tax.Footnote 95 Yet just within the next few years he recorded having spent £25 at the central common law courts to sue out a writ against the partial assize jury.Footnote 96 The Catesby roll likewise tells us in the preamble that the rich woodlands of Wappenbury had set Robert Catesby back £106 13 shillings and 4 pence, while the estate in Ullesthorpe cost 140 marks (£93 6 shillings 8 pence). A running cost in the margins of the first few membranes reveals that he had almost equalled his spending on Ullesthorpe at law in just the following few years, spending some £84 at the assize sessions in the early 1440s.Footnote 97 That the various suits of the elapsing years had impoverished Nicholas Catesby by the end of the century is corroborated by suits for debt worth £100 brought against him around the same time, and by the seizure of his lands in Northamptonshire after his death to repay his creditors.Footnote 98 Little wonder, then, that neither man was willing to let all of this be forgotten on their deaths; these narratives were, in a sense, emotional outlets.

They were also documentary testimonies. Their remembrance of so much detail – in Nicholas Catesby's case, back into his father's lifetime – relied on the accumulation of legal and personal paperwork, a process to which both narratives refer. Pilkington's story routinely describes his diligence in acquiring copies of documentation produced during litigation for and against him. In 1493, while trailing after the itinerant royal council, he ensured that each of his appearances was ‘indo[r]syd on ye backes of ye suplycacions … put up to ye said lordes’, to ‘remain in ye kynges counsayle chamber’.Footnote 99 The original records no longer survive but Robert's copies must have been conveyed safely back to Rivington, where they were viewed and copied in the mid seventeenth century.Footnote 100 Likewise, in the wake of the assize of 1498, Robert ‘[r]ode to ye jugges … & ye privatore of ye courte’ at Derby Abbey and there ‘toke owte copes of ye juggement’. At one point his narrative appears to have been copied verbatim from one such document: an answer that Robert had been asked to compile for Thomas Savage so that he ‘myght be syght of ye said wrytyng be fresch in his remembraunce’ of the Mellor case upon his return from an overseas trip with the King in 1500.Footnote 101 The rest of Pilkington's book is less explicitly cited but reflective of his fastidious record-keeping. Just before his death in 1508 two of his ‘boxes with old evidences in’ were passed to William Orrell, a lawyer and family acquaintance, presumably including documents relevant to the Mellor dispute – as well as the narrative that framed them.Footnote 102

The direct utility of existing papers is more obvious still in Nicholas Catesby's manuscript. Alongside the English petitions and Latin memoranda copied from his own suits, notes in the margins of his first few membranes make reference to external documents from which particular details were derived. Some of that material was legal paperwork: the 1440s assize of novel disseisin recounted early in the roll was summarised ‘Ut per Recordum assisae’ (‘as per the record of the assize’), while his father's recovery of the lands comes ‘Ut per deposiciones Roberti Miriell [de] Newenham & aliorum’ (‘as per the depositions of Robert Miriel of Newenham and others’). The account of the union between Margaret Metley and John Hugford and its consequences is taken from more personal sources, appearing ‘Ut per dictum Roberti Catesby [de] Newenham’ (‘according to the saying of Robert Catesby of Newenham’), meaning Nicholas Catesby's father, and ‘per litteram Thom[e] Huggeford’ (‘by the letters of Thomas Hugford’), John Hugford's father.Footnote 103 Although these annotations are in the same hand as the main text they appear in a different, slightly lighter brown ink; one that also appears in interlineations throughout the roll. These additions seemingly represent a secondary phase of writing and another round of consulting original documents, after the narrative was first drafted. One extra detail plucked out on further examination of the assize record and added between existing lines of text, for example, was that John and Margaret Hugford had ‘promysed feithfully to fynde a prest to synge ij yere for [Nicholas Metley's] soule’, using funds from the sale of Metley's estates. These amendments illustrate in black and white how Nicholas Catesby was engaged in crafting an account from, rather than simply a compilation of, his family's records of this dispute.

Amongst those records was preserved a model for this interpretive format of record-keeping: the ‘roll of evidences’ produced by John Catesby, Nicholas's grandfather, a century earlier. This much longer manuscript comprises original grants and leases pertaining to lands that John claimed in Ladbroke, Warwickshire, as well as pleas of assize and King's Bench presentments that he actively pursued in the 1380s and 1390s, bound together in roughly chronological order. Some of these documents are stitched on top of an ‘extensive piecemeal narrative’, in Law French and sometimes in the first person, which outlines the dispute and places it against the backdrop of the period's political events. So, much like Nicholas Catesby's plotting of his family's fates alongside those of the Yorkist kings, John Catesby pinpointed a downturn in his fortunes to the fall of a principal supporter, another Earl of Warwick, and to a lapse in litigation around the time of Richard II's deposition in 1399. It is not implausible that Nicholas had sight of this document, and that it influenced the tone of his own tale, its format as a Chancery-style roll, and its construction around transcribed records.Footnote 104 In addition to a rapidly growing archive on which to build cases, writers of this ilk appear to have benefitted from intergenerational familiarity with glossing that archive, too.

There is, in fact, a noticeable trend towards such narrative-writing among the gentry peers of Pilkington and Catesby in the fifteenth century. Another example connected to the wider Catesby affinity is a first-person account written by Warwickshire gentleman John Brome, which describes various trespasses committed against his properties in Warwick and Baddesley in 1450. This John Brome was not only the father of Nicholas Brome, later Nicholas Catesby's opponent at law, but also had his own, separate disputes with William Catesby in the 1460s.Footnote 105 Very similar texts were produced elsewhere in the fifteenth-century English midlands, as discussed above; Eleanor Stafford's roll concerns lands in Northamptonshire, while the slightly earlier manuscripts of the Armburgh family and John Catesby are from Warwickshire.Footnote 106 No two bear exactly the same form or structure, but they share a preference for colourful story-telling above the solid ground of transcribed deeds. Indeed, Nicholas Catesby's roll is the only example under discussion here that gives so much space to verbatim copies rather than summaries. Some, like the account probably written in the later 1430s by Joan Armburgh, stand out much more for their ‘lively idiosyncratic vituperation’. Joan's central conceit was that every official who stood in the way of the Armburgh family at assize sessions and at the chancery offices had been instantly smote by God: one justice was reportedly stricken ‘with sykenesses with inne a day or two arte most and was dede [and] beryed with inne [a] fourtenyght’.Footnote 107 John Brome likewise emphasised the terrible ‘enbaldisshing of all other suche riotto[r]s in other countreys about … in that tyme and seasen of rebellion’ should the raid on his home, committed right under the noses of the king and the earl of Warwick, go unpunished.Footnote 108 Unsurprisingly each surviving example bears the hallmarks of the social disorder of their age, and the consequent difficulty in getting anything resolved.

Moreover, each of these narratives was created at the same, very specific moment in their authors’ lives: towards their very end. As we have seen already, Pilkington's ‘Narrative’ reports that he had ‘lay a quart[er] of a yere in perell of deth’, by which time he could ‘doo no more but dayly pray to all mighty Jh[esus] to bryng the said byschope [Thomas Savage] to amendement’ – another reference to the real target of his grievances.Footnote 109 Nicholas Catesby died not long after the production of his roll and its terminal events in c.1500, by which time his eldest son, another Nicholas, had predeceased him.Footnote 110 His grandfather, the elder John Catesby, lived only a few years beyond the latest events chronicled in his substantial roll, while Joan Armburgh's narrative may have been an ‘aide-memoire’ produced just before her own death in 1443.Footnote 111 Shorter summations of lingering disputes sometimes feature in that more common end-of-life documentation, the last will and testament, where some chose to air grievances rather than forgive them.Footnote 112 Without surviving examples for Robert Pilkington or for Nicholas Catesby we cannot know if they used their wills in this manner. Yet their narratives likely had the same audience and the same intended effect: the next generation, and the claims and contests they inherited.

The death of principal landowners threatened their remaining family members with downward mobility, through means including (but not limited to) legal proceedings to snap up any dubious estates.Footnote 113 An episode recounted in Nicholas Catesby's roll provides a glimpse into the anxieties such uncertainty created. In the winter of 1485, the ailing John Hugford was apparently willing to show Nicholas Catesby ‘gode love & favor’ by trying finally to resolve their property dispute. Hugford was perhaps moved towards this sudden clemency by the need to tidy up his affairs, since his three heirs (including the two-year-old John Beaufo) were within age and set to inherit a rather confused group of estates. He died before any arbitration could take place.Footnote 114 By contrast, both Robert Pilkington and Nicholas Catesby had adult sons to whom they could bequeath their disputes, lessening the need to give up on any claims. We know that both Nicholas's second son, the younger Robert Catesby, and Richard Pilkington dutifully took up their fathers’ mantles by initiating their own lawsuits in the early sixteenth century.Footnote 115 Much like the cartularies and deed books kept by property owning families of this time, these documents were produced in anticipation of further encounters with the law, then.

The version of events being passed down therefore required a certain rhetorical flair and persuasiveness. Comparing the two principal examples here with external evidence suggests that, in these cases at least, the goal was to simplify the details of the disputes and litigation therein described. Beyond Robert Pilkington's book, the long entry in the relevant plea roll for his error case at King's Bench in 1498 helpfully contains copied records from the contested Derby assize, which confirm that the Mellor issue had many more moving parts than Pilkington himself seemed willing to admit. It concerned not the whole manor of Mellor but a specific set of messuages, meadows, pastures, and woods there – which, the assize jury contended, Pilkington had failed to properly enumerate before them. Each had descended to Pilkington by way of different ‘gifts’ made by John and Ellen Ainsworth to their daughter, Katherine, explicitly in the absence of any legitimate male heirs. Pilkington's narrative does not deny these realities, but it does smooth them over in favour of a tale of natural inheritance interrupted by unnatural heirs, of oppression at the hands of a noble family, and of justice diverted by intimidation.Footnote 116 He, like Nicholas Catesby, sought to offset the changeability of landholding and litigation with a narrative emphasising continuity.

There were practical reasons for such editorialising, beyond sheer partiality. In the first instance, it was necessary to straighten out the shifting terms of legal arguments waged over such a long period of time.Footnote 117 What started as a straightforward attempt by Pilkington to confirm his lineal title, as established above, eventually became an endeavour to wield the power of the central common law courts in overturning the ruling of the 1498 assize, for example. Likewise, while the suits brought in the lifetime of Robert Catesby had consistently revolved around the legality of his purchase of Metley's estates as an executor, by the 1490s the dispute's parameters as presented before the law had become more flexible. Initially Nicholas Brome, Gerard Danet, and Ricard Cotes claimed before Star Chamber that they had rights to Wappenbury and Ullesthorpe as husbands to the Metley heiresses (or, in Brome's case, as guardian to their offspring), inherited upon the death of John Hugford.Footnote 118 Yet later on, having forced Catesby to submit a more detailed second bill, the three defendants deployed a different tactic. They alleged in a further round of pleading that, since the orphaned John Beaufo was within age and ‘in the kynges warde’, Catesby ‘can not ne ought by any lawe to put the enh[er]itaunce & right of the seid enfaunt to trial with due serch of the kynges title’.Footnote 119 The matter had morphed into one concerning wardship and Catesby's capacity to interrupt it, presumably in order to delay the suit. Producing a neat chronological account of litigation over a single estate must have assisted in keeping track of such changing terms, especially as litigants hopped between courts and jurisdictions.

Changing social networks and geographical loci could also alter the sway of later recollections, and had to be smoothed over in the writing up. Nowhere is this more apparent than in a small, unassuming document in the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust archive which, remarkably, supplies another version of the Catesby disputes in Warwickshire.Footnote 120 A much shorter memorandum, given the later title ‘A case touching Baddesly’, it essentially corroborates the basic facts of Nicholas Catesby's story so far as the Metley bequest of 1437 and the decisions of its executors were concerned. Its anonymous author relates that Robert Catesby purchased the manor of Baddesley Clinton from the Metleys too, and that he ‘made alwey suyt yerfor’ in the decades that followed. That manor was up for sale at Nicholas Metley's death, and local historians have associated both Robert and Nicholas Catesby with spells at Baddesley Hall.Footnote 121 Yet it is never mentioned in the Catesby narrative and nor do Wappenbury and Ullesthorpe appear in this shorter text. The centring of Baddesley suggests that this memorandum was made by and for its owners: the same Brome family that Nicholas Catesby grappled with over other Warwickshire estates. Notwithstanding their enmity elsewhere, however, the Brome memorandum accepts that the Catesbys ‘entered pesibly’ into Baddesley and held it ‘without interuption’ until John Hugford seized it ‘with stronge hande’. Thereafter, it was ‘John Beaufo Gerard Danet & Ric Cotes … pretending as in right of their seid wiffes’ who had ‘forcibly of late entered in to ye said lands & disseised the seid Nich Catesby’ – so, the Catesbys are the victims in this story, too. Noticeably omitted here is Nicholas Brome, then lord of Baddesley, and his role in the disseisin of the Catesby estates and the guardianship of young John Beaufo, as described in Nicholas Catesby's suit against Brome, Danet, and Cotes in Star Chamber in the 1490s.

All of these contradictions exist between the Catesby narrative and the Brome memorandum despite the evidence that they were written around the same time. The latter also ends on the lingering Star Chamber suit of the 1490s, and recites the claim made there that any ‘sale made by the seid ij executors [of Metley's will] un to the iijde [was] voide in the law’.Footnote 122 The apparent conflation of the Brome and Catesby perspectives by the beginning of the sixteenth century might be explained by the marriage of Nicholas Brome to Lettice Catesby, daughter of Nicholas Catesby (see Figure 2).Footnote 123 The production of such distinct accounts may also reflect the tendency among landed families to divide records and accounts into specific estates. That would explain why Nicholas Catesby likewise omitted from his narrative the contemporaneous litigation between his paternal cousins Sir William Catesby (IV) and George Catesby and the Bromes over various properties in Warwickshire, as is revealed in other documents filed alongside it in the ‘Catesby Papers’.Footnote 124 Although this information might have alluded to general vexatious behaviour on the part of the Bromes, Nicholas Catesby opted for a more linear account of his own pursuit of Wappenbury and Ullesthorpe.

Much harder to explain is Nicholas Catesby's omission of an apparent success in that very pursuit. Other documents within the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust archive reveal that in June of 1462 the Chancery had been called upon to investigate the terms of Nicholas Metley's dying wishes. While the instigating complaint or information is not known, the resulting process produced testimonies from two of the men who had gathered around Metley's deathbed some twenty-five years earlier. Crucially, both confirmed that Metley had allowed the purchase of Baddesley, Wappenbury and its appurtenances, and Ullesthorpe for the health of his soul, and that Robert Catesby had been named an executor. They also stressed that instructions had been conveyed to a clerk to have the testament written down. A later hand appearing on the surviving documents (probably that of Edward Ferrers, from the seventeenth century) suggests that on the basis of these depositions ‘[the will] had been prepared and taken to be engrossed – and was so proved in Chancery’.Footnote 125 That would have been a considerable victory for the Catesby cause, and yet the resulting narrative makes no mention of these hearings or any proving of the will that might have resulted (nor does the proven will itself survive).

As it happens, the case falls into a gap in the narrative's chronology between the Battle of Towton in March 1461, which drove the Catesbys into Scotland, and the pardon granted to Sir William Catesby (III) in December 1462, which elicited a new wave of arbitration.Footnote 126 The only suggestion that anything had changed in the time being comes in the description of arbitration hearings held shortly thereafter, at Warwick and Coventry in the early 1460s. There, John Hugford reportedly argued that ‘Nich Metley died intestate’, presumably on the basis that verbal wishes did not have the strength of a written testament. Yet in response Robert Catesby was then able to show ‘the testam[en]t with the p[ro]bate of the same under waxe’.Footnote 127 Assuming that this proving really did take place in 1462, allowing Robert Catesby the chance to finally confront the argument made by his opponents up to this point, why exclude such a moment of victory in the retelling? One possibility is that it simply suited Nicholas Catesby to eliminate any impression that legitimate doubts had ever surrounded the arrangements made at Metley's death. Another, equally compelling reading is that it was more powerful to claim that a dispute had never been well handled at law; that it had proven entirely unresolvable, despite best efforts, in the face of an unjust system.

This begs the question, finally, of what benefit such a constructed account could have had even for heirs, who presumably might have needed all the relevant information to hand if they did not know it already. It is not impossible, given their noted similarity to supplications, that these narratives were intended for the eyes of clerks and judges in law courts, to serve both as collections of proofs and as first-hand testimonies from beyond the grave. We have seen already that Robert Pilkington had been asked to summarise his case to date for the busy Thomas Savage, a judge in the king's council.Footnote 128 Dame Eleanor Stafford likewise directed the articles in her deed roll for Dodford to ‘your lordships’, implying that she expected a courtroom audience; on this basis Simon Payling proposed that the roll was part of the evidences presented to Edward IV and his council in c.1481.Footnote 129 John Brome's short narrative was similarly described as matters which ‘the same John Brome wole evidently prove, as it shall seme and bethought to every man of wyse discression’, implying an expectation for further proceedings.Footnote 130 All of this being said, that the narrative creations of the Catesbys, Pilkingtons, Armburghs, Bromes, and Staffords would have been acceptable legal evidence in most jurisdictions seems unlikely. To begin with, they did not have the required status of original documents with evidential value at common law. Moreover, they have largely come down to us through the family rather than the judicial archive, suggesting that if they were ever submitted to courts they ended up, ultimately, with an audience back home.

This lack of overt legal purpose does not mean that such narratives had no utility in the pursuit of future suits. The sheer force of will in the face of failure they portrayed would itself have had some force before the law, as legally trained writers like Nicholas Catesby must surely have known. By the late fifteenth century the duration of a person's occupation of certain lands could be enough to confer lawful possession of those lands, the exact length of time required depending on jurisdiction.Footnote 131 So too, it seems, could the persistence with which a dispossessed party had made ‘continual claim’ or ‘clamour’ for their title play a role in judgment. If due ‘clamour’ had not been made, a claim might be deemed relinquished. Anxiety about proving continuity of clamour appears in the aforementioned Brome memorandum, which mentions pointedly that Robert Catesby had maintained ‘his possession in ye same xxti yeres and more without interupcion’ and also that he made ‘contynuell clayme’ to Baddesley.Footnote 132 Examples of the same rhetoric appear elsewhere, too. Another is furnished by Humphrey Newton's history of his family and lands, written into his commonplace book in the early sixteenth century, which also paused to note that ‘the seid heires of Neuton have nat had ye seid londe yet they have ever made contynell clayme wherby they may entre by the lawe’. The link between protested and real right is especially plain here.Footnote 133 Conversely, as both Robert Pilkington's King's Bench plea and his narrative reveal, his plight for Mellor had failed at the 1498 assize partly because it was felt that Robert had not ‘contenually claymed’ his estate.Footnote 134 It is not implausible that it was with the aim of illustrating continual claim that this form of narrative-writing emerged, a product of the age's ‘documentary revolution’ but also of a particular confluence of status anxieties, selective memories, and fluid interfamilial relations.Footnote 135

Contrary to any lingering suspicion that civil litigation was somehow second nature by the early modern period, these lengthy diatribes reveal a considerable depth of feeling about land and about the legal challenges to getting it back. This was true even for members of the English gentry, the age's most prolific and therefore (it might be assumed) habitual litigants. As landowners they had the benefit of curated archives of deeds and documents, of course, and in producing narrative accounts to frame them they acted on a growing impulse for autobiographical expression and ‘commemorations of the self’.Footnote 136 Remaining traces of those archives for both the Pilkingtons and Catesbys have made it possible to tease out what kind of commemoration they aimed to construct. They sought to capture salient accounts of complex and changeable disputes, even omitting seemingly crucial information, to exonerate themselves from accusations of not having done enough themselves and to bolster future generations’ efforts to sway legal authorities. Returned to the family archive, their manuscripts had a longer-lasting utility still; primarily, as a means to continue their claims into the next generation.

5. Conclusions