Introduction

In 1921, Kurt Woermann, head of the Hamburg-based trading company C. Woermann, travelled to Liberia. His ship had just dropped anchor when a boat of Kru mariners flying the Woermann flag approached.Footnote 1 The headman of the boat carried another Woermann flag slung around his hips. The Woermann family narrative includes the following words from the headman:

I am Chief Toby. I come to greet Chief Woermann and bring him ashore. […] We want to see your trading houses and steamships on this coast again. If you have no money, we will buy up products for you and ship them to Hamburg. Cocoa, coffee, piassava – whatever you want. You will sell it in Germany and send us goods in return. We trust you because we have known you for so long.Footnote 2

This apocryphal anecdote testifies to the Woermann family's self-conception in the post-First World War period.Footnote 3 Kurt Woermann was determined to start business relations with Africa anew. In telling this episode, he meant to underline the fact that C. Woermann had a long tradition of trade with Africa, which dated back to the time before the colonial partition of the continent. He wanted to demonstrate that the economic and personal relations established over decades had elevated his company to a particularly prominent position. This should have enabled Woermann to continue his business smoothly – had it not been for the political upheavals of the post-First World War period. The accusations made in the Versailles peace treaty that Germany was unfit to colonise deeply affected those Germans who felt a strong personal connection to the colonial project. They perceived this as an unjust affront. According to their narrative, Africans themselves wanted to start trading with German companies. German colonial rule could not, therefore, have been as bad as the allied powers pictured it.

What became evident in the Paris peace negotiations, however, was that the rigid chronological boundaries of the end of empire were beginning to blur. While German colonial rule ended, it did not end the colonial domination of the territories formerly ruled by Germany. The allied powers were not willing to return Germany's colonial possessions, and the justification that Germany had proven itself incapable of governing colonies outraged the German side across party lines. Attempts to at least credit the cession of the colonies against the demanded reparation payments failed. The Treaty of Versailles was finally signed on 28 June 1919, and Article 119 of the treaty stated that Germany ‘renounces in favour of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers all her rights and titles over her overseas possessions’.Footnote 4 The former German colonies were placed under the mandate rule of the League of Nations, who transferred them in turn to Great Britain (parts of Togo, Cameroon and German East Africa, today Tanzania), France (parts of Cameroon and Togo), South Africa (German South West Africa, today Namibia), Belgium (parts of German East Africa, today Rwanda and Burundi), Australia (German New Guinea), New Zealand (Samoa) and Japan (Jiaozhou, islands in the northern Pacific).Footnote 5 The German inhabitants of the mandated territories were expelled – with the exception of South West Africa. Moreover, the financial and economic provisions regulated the expropriation of German possessions and all property by the mandate powers without compensation. For many German colonial companies, this meant the total loss of investments, land and other assets.

In the historiography of German colonialism, the fate of German companies after the end of the First World War occupies a rather marginal position.Footnote 6 In older research, the framework of German formal colonial rule from 1884 to 1919 dominated the research agenda. Although research on German colonial history avant la lettre and on the afterlife of German colonialism has flourished in recent years, it has mainly been concerned with cultural phenomena and political agitation for the (re)acquisition of a German colonial empire.Footnote 7 In general, German colonial companies can be considered among the losers of the inter-war arrangement. Excluded from profitable markets in the former colonies, the new political order posed a serious threat to their existence. But some companies were able to successfully adapt to the new situation. The division into winners and losers in the (post-)imperial context was not as clear-cut as it seems at first glance.

I argue that an important ‘imperial afterlife’ was the continuing, concrete economic interest of German companies in African markets. Thus, transcending the formal end of colonial rule, the article follows Gallagher and Robinson's thesis that for ‘purposes of economic analysis it would clearly be unreal to define imperial history exclusively as the history of those colonies coloured red on the map’.Footnote 8 While Gallagher and Robinson's empirical analysis was primarily focused on the nineteenth century, their approach nonetheless provides significant avenues for considering imperialism beyond formal colonialism. Empires are not just shaped by political rule and formal boundaries. Economics is a vital part of imperialism. In the case of Woermann, the ‘life’ of a business operating in the framework of global capitalism took on colonial dimensions, too. Furthermore, delving into the evolution of C. Woermann after 1939, one can observe how the dissolution of colonial business prompted the firm's organisational reconfiguration in alignment with National Socialist policies in Eastern Europe, effectively merging one imperial project into another. This transformation, driven by both economic necessity and political ideology, sheds light on the adaptive nature of imperial enterprises in response to the shifting geopolitical landscape. Using the example of C. Woermann, I examine how a company that had grown into a multinational corporation in a symbiotic relationship with German colonial rule found its way in a new world order – from expansion to contraction. To this end, I reconstruct the company's attempts to re-establish itself in Africa after the loss of the German colonies, how it tried to regain a foothold in these former colonies and how, from 1933 onwards, National Socialist imperialism led to a reorientation of C. Woermann's colonial business.

Woermann's Colonial Business

On the eve of the First World War, the company management was in an optimistic mood. In November 1912, C. Woermann celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary.Footnote 9 Around 350 people gathered at the prestigious restaurant ‘Uhlenhorster Fährhaus’. Senior director Eduard Woermann gave a speech in which he praised the history and future of the company and commemorated the work of the forefathers Carl Woermann, Eduard Bohlen and Adolph Woermann, who had ‘earned an irreplaceable merit’ for the ‘flourishing’ of the company.Footnote 10 Adolph Drücker, who had been appointed by Eduard Woermann as vice-director of both the Woermann Line and German East Africa Line, noted how much the common mourning for former owners and managing directors such as Adolph Woermann had created a ‘feeling of togetherness’ among the company's employees. He concluded his speech with the hope that this celebration should provide a fitting occasion to ‘swear allegiance to the men who stood at the head of the C. Woermann company’.Footnote 11

Woermann's ‘life’ as a trading firm is a prime example of the importance of economic analyses to interpreting imperialism. The Woermann Group's roots lie in a time before Germany had formal colonies. The company grew in a close relationship with the German colonial empire, and then outlived it. There is hardly any other economic enterprise that has been so closely associated with German colonial rule in West and South West Africa over such a long period of time as the Woermann Group, which emerged from the trading house C. Woermann, founded by Carl Woermann in 1837.Footnote 12 In addition to the parent company C. Woermann, the business group comprised, among others, the shipping line Woermann Line (founded in 1885), the plantation company Kamerun Land- und Plantagengesellschaft (1885), the shipping line German East Africa Line (1890) and the trading company Woermann, Brock & Co. (established in 1893 as Damara & Namaqua Handelsgesellschaft). At the heart of the group was the Woermann family, whose relationships, intergenerational and trans-regional networks, personal commitments, and capital ownership and management, united the otherwise legally independent companies under a single roof. C. Woermann was the nucleus of a colonial business network that was connected by contractual cooperation, personal relationships, shareholdings and capital flows. The trading house, which had been operating in West Africa since the middle of the nineteenth century, was one of the most important German companies in Africa before the founding of the colonial empire in 1884. It exported European consumer and industrial goods such as cotton fabrics, kitchenware, weapons and alcohol to South America, Southeast Asia and West Africa, and imported tropical raw materials and agricultural products such as rattan, rice, coffee, palm oil and rubber to Hamburg. The company was thus an important actor in the nineteenth-century process of globalisation that rapidly accelerated due to technical innovations and political transformations. After establishing a trading post in Liberia in 1850, further permanent branches followed in Gabon and Cameroon as early as 1862 and 1868 respectively. Although C. Woermann maintained trade relations with North and South America and Southeast Asia until the 1880s, the company increasingly concentrated on business in West Africa, a region that not only experienced the gradual transition from slave to ‘legitimate trade’ in the nineteenth century, but also the colonial division among the imperial powers of Europe, in which the company directly participated.Footnote 13

Following the death of the founder Carl Woermann, his son Adolph Woermann (1847–1911) headed the company between 1880 and 1909 and became its defining figure. Within a few years, he became one of the best-known and most influential political merchants of his time. He systematically expanded the family's colonial business and, through a network of social and capital entanglements, created the Woermann Group. Adolph Woermann was followed by his half-brother Eduard Woermann (1863–1920), who ran the company from 1909–1920. For over thirty years after Eduard Woermann's death, Adolph Woermann's son Kurt Woermann (1888–1951) managed the parent company C. Woermann.

The Woermann Group's symbiotic relationship with German colonial rule continued for several decades. A key factor in this was the founding of the shipping line Woermann Line in 1885, which over time came to play a prominent role in the family group. The Woermann Line rose to become the largest German shipping company in West Africa and an important cornerstone of the German colonial economy in Africa. Its significance as a central transoceanic link between the German Empire and the colonies in West Africa was magnified by the fact that it remained the only German shipping company to offer permanent liner services in the region until 1906. Significantly, the Woermann Group had a virtual monopoly on shipping troops and supplies during the genocidal war against the Herero and Nama in German South West Africa (now Namibia) in 1904–1907.

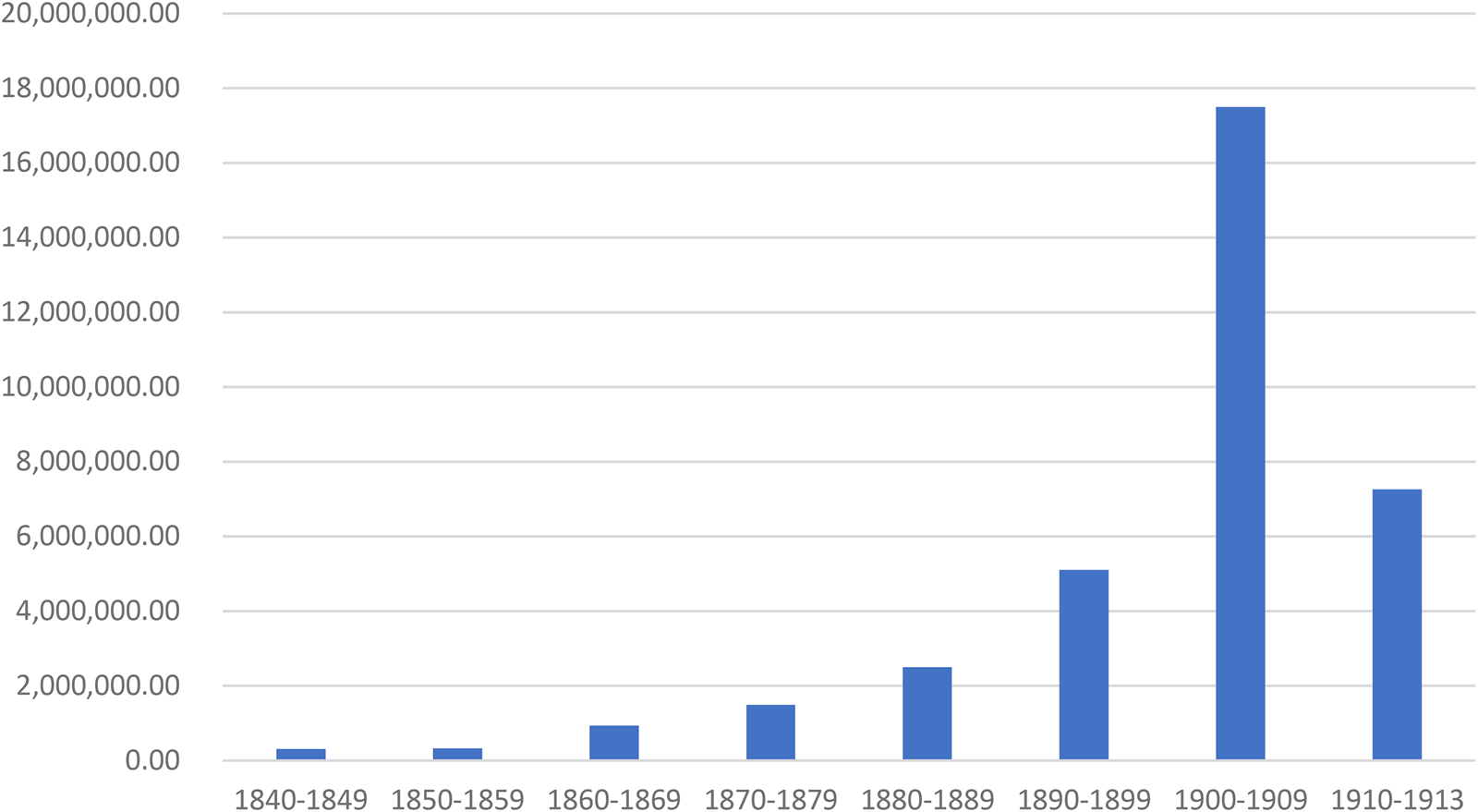

At the time of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the parent company in 1912, the Woermann Group had reached its economic peak. C. Woermann and the Woermann Line were generating record profits. From a business perspective, the decade before the start of the First World War was the most successful in C. Woermann's company history, with absolute peaks in 1905 and 1909. This trend had already been emerging since the end of the 1890s, driven primarily by income from the shipping business, the rubber and palm kernel trade, and profits from shared assets. In the three years before the start of the First World War alone, the group generated a total of 7.2 million marks, almost exactly as much profit as in the two decades before the turn of the century combined (a total of 7.6 million marks) (Figure 1).Footnote 14

Figure 1. Profits of C. Woermann (1840–1913) in marks (sums).

Source: C. Woermann company archives, balance sheets.

Despite this prosperity, the close connection of the family business with German colonial rule had already begun to dissolve. Before the Woermann Group folded in the First World War, the trading company in particular was losing importance for the German colonial economy. In the overall economic structure of Cameroon, C. Woermann had been one company among many since the end of the 1890s, losing its status as the largest company in the region. Financially powerful joint-stock companies, such as plantation companies and concessionary companies, absorbed a large part of the export turnover and reduced the importance of C. Woermann. In addition, competition from younger and more agile companies intensified. The Woermann Line, for its part, had lost its unique position in West Africa shipping and had been forced into an alliance with its fiercest competitors in the German Empire, Hamburg's HAPAG [Hamburg America Line] and Bremen's Norddeutscher Lloyd. Its former importance as the only German shipping line in West Africa was thus greatly weakened.Footnote 15 Despite this symbolic decline, however, the Woermann Group continued to thrive economically, achieving the highest profits in its history in the pre-war years.

Navigating Crisis: From Expansionist Fantasies to Dissolution

The First World War was the most profound turning point in the history of the Woermann Group. The onset of the war affected the shipping, trading and plantation businesses in equal measure. The company headquarters in Hamburg was cut off from all communication with its branches early on. Most of the ships of the Woermann Line and German East Africa Line were confiscated by the Entente powers – especially Brazil and Portugal – in the course of the war.Footnote 16

Nevertheless, the management of the Woermann Group initially saw the First World War as an opportunity to expand its colonial business. When the discussion of war aims gained momentum in the German Empire at the beginning of 1915, the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce asked Hamburg overseas companies about their wishes.Footnote 17 Among the eighteen companies approached were C. Woermann, the Woermann Line, the German East Africa Line and Woermann, Brock & Co. from the Woermann Group. In his statement for C. Woermann, Eduard Woermann emphasised the difficulty of making predictions given the uncertainty surrounding the war.Footnote 18 But despite this caveat, he outlined an extensive colonial programme. An important aspect of the post-war order, he wrote, was to ensure free market access for German firms by concluding free trade agreements with other colonial powers. An ‘open door principle’ was to be established, combined with most-favoured-nation treaties, but, he added, ‘of more certain use than all such most-favoured nation and equal opportunity treaties, however, are always our own colonies, and so we hope that Germany will succeed in acquiring new colonies in Africa in addition to the old ones, and here our wish can generally only be: “as much as possible”’.Footnote 19 Eduard Woermann also proposed annexing the Congo state to create a ‘Central African Empire’ and establish a territorial connection between Cameroon and German East Africa.Footnote 20 He declared that it would be desirable to annex the independent state of Liberia as well as the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique.Footnote 21

The Woermann Line struck the same chord of colonial expansionist fantasies: ‘As a West Africa Line, we are striving to enlarge our West African colonial possessions’.Footnote 22 Like C. Woermann, the Woermann Line called for a contiguous Central African colonial empire, but one that would include French West Africa as well as Angola and the Congo State. Both C. Woermann and the Woermann Line also urged that Togo should remain a German colony, as the wishes to create a contiguous Central African Empire would have been expressed by other companies partly by ‘sacrificing Togo’.Footnote 23 However, both companies insisted on the importance of Togo as one of the main markets for palm kernels, ‘whose European market was and must remain Hamburg’.Footnote 24

Already evident in the wishes expressed for the colonial post-war order were the different objectives of the companies belonging to the Woermann Group. While C. Woermann and the Woermann Line were in agreement on this issue, Woermann, Brock & Co. advocated giving up Togo in favour of a huge Central African colonial empire, which, in addition to the German colonies, was to include not only Angola and the Belgian Congo state, but also the French and Portuguese Congo (Gabon and Cabinda) as well as parts of Mozambique.Footnote 25 In contrast to the other two Woermann firms, however, Woermann, Brock & Co. also urged that, in the event that it was not possible to secure the German colonies militarily, they should consider completely renouncing their own German colonies in favour of an open-door policy in the colonies of other European powers.Footnote 26 If colonies could not be defended ‘at all times and against any enemy’, it would be better to renounce all colonial possessions altogether.Footnote 27 Woermann, Brock & Co. was obviously influenced by the rapid military defeat in the German colonies and the realistic possibility of the permanent loss of German South West Africa.

The open-door principle for German companies was a basis on which all companies of the Woermann Group could agree and which shaped the companies’ position in the post-war period. Eduard Woermann summed up this principle programmatically: ‘The ultimate goal of German colonial policy will have to be that German merchants find that degree of freedom of movement in every region of the world which enables them to fulfil their economic intentions and which they may reasonably expect their fatherland to secure.’Footnote 28 Eduard Woermann advocated this principle even against protectionist demands from German merchants. He opposed demands to use differential tariffs in the German colonies as a means of political pressure because these would endanger the open-door principle.Footnote 29

With the looming threat of losing the colonies, this principle became even more important. At the end of 1915, the Woermann companies jointly sent a memorandum to the Reichskolonialamt (Imperial Colonial Office) in which they once again pointed out the importance of the open-door principle in light of ‘the reality of the seizure of German South-West Africa by the South African Union’ and the possibility that the colony could be ‘permanently annexed to the British South African colonial empire’.Footnote 30 In the case of German South West Africa, however, it would not only be a matter of classic most-favoured-nation treaties, but also of politically ensuring that people of German descent all over South Africa were put on a fully equal footing with the British colonisers, also with regard to appointments to civil servant positions and public offices. This was the only way to prevent ‘Germanness’ from being ‘systematically eradicated’.Footnote 31

While the Woermann Group had joined in the chorus of colonial expansionist fantasies at the beginning of 1915, annexationism soon gave way to the pragmatic realisation that once peace was concluded, it would be difficult to resume the family group's business. The group was dissolved during the war. The owners had realised that the simultaneous reconstruction of both the shipping company and the trading company would overstretch the resources of the family. In 1916, the Woermann family members sold their remaining shares in the Woermann Line and German East Africa Line to a consortium consisting of HAPAG, Norddeutscher Lloyd and Hugo Stinnes. The contractually stipulated personal union between the management of C. Woermann and the executive and supervisory boards of Woermann-Linie was completely dissolved.Footnote 32 Lothar Bohlen and Arnold Amsinck, who were both part of C. Woermann's management and the Woermann Line, gave up their partnership in C. Woermann and became board members of Woermann-Linie, and Amsinck took over as chairman of the board. This constituted the complete separation of the trading company C. Woermann from the Woermann Line and the German East Africa Line and reversed the development from a trading company to a family-owned group.

After the war, the companies were mere shadows of their former greatness. The entire fleet of the Woermann Line and the German East Africa Line were either confiscated during the war or had to be handed over to the victorious powers. Even after their merger with the Hamburg-Bremen Afrika-Linie to form the Deutsche Afrika Linie (DAL), the fleets of the Woermann Line and the German East Africa Line did not reach the size they had before 1914. In terms of tonnage, the DAL did not return to its pre-First World War volume until 1977.Footnote 33

The trading company C. Woermann lost its factory system in Africa, and its properties in the French, British and former German colonies were expropriated. In the French mandate territory of Cameroon alone, sixty-three C. Woermann properties with a total value estimated by the French authorities at 887,183 francs were expropriated.Footnote 34 The Bimbia plantation in the British mandate territory was also confiscated. In total, C. Woermann's expropriated assets in Africa, based on the values of the respective branches in the internal balance sheets, amounted to about 1.8 million marks, an amount that was significantly higher than the annual turnover in the first post-war years, yet was only a small fraction (7%) of the company's total assets.Footnote 35

In the Slipstream of Empire

In a classical historiographical narrative, our story would end at this point. But as the German Empire dissolved, the Woermann businesses decoupled from the colonial empires and took on an imperial (after)life of their own. Over time, German companies found business opportunities in the colonies of other imperial powers. Crucial to this reintegration was the racist order of the colonial world with its binary distinction between colonisers and colonised.

Before this economic reintegration could be completed, however, political hurdles had to be overcome. After their expropriation, German companies were effectively excluded from both trade with and direct presence (ownership, investment) in the former German colonies and from establishing themselves in British and French colonies. Following their collapse as a result of the First World War, the reconstruction of most German trading companies in Africa was geared towards re-establishing traditional ways of doing business overseas. This required the restoration of freedom of establishment for German companies in the colonies and mandate territories. In British West Africa (Sierra Leone, Gold Coast, Nigeria), the ban was lifted in 1923.Footnote 36 In 1925, the restrictions were also lifted in the British Mandate territories.Footnote 37 Corresponding preconditions for business with the French colonies and mandate territories were only created by the trade treaty between Germany and France of 1927.Footnote 38 This chronological difference partly contributed to the fact that British West Africa and Liberia became focal points of Hamburg's African business in the interwar period.

Before settling in the British colonies and mandate territories, however, C. Woermann's branches were reactivated in Liberia and in Eloby, Spanish Guinea. The long-standing relationships of the family business, in particular, and the economic networks that developed from them, supported these re-establishments. In Eloby, apart from coffee, cocoa and rubber, it was above all the high-quality okoumé wood that C. Woermann exported, and which soon dominated the export statistics of the region.Footnote 39 Besides Spanish Guinea, it was in the independent state of Liberia that the company re-established direct trade relations for the first time after the war. This was no coincidence: C. Woermann's entire West African trade began in Liberia in the middle of the nineteenth century. After the First World War, Liberia's formal independence appeared to offer favourable conditions again. The decades-long relationship between C. Woermann and Liberian traders, merchants and seamen was a further advantage. Beyond its function as self-affirmation and exoneration, the aforementioned episode with Kurt Woermann and Chief Toby points to the role of trust in long-distance trade, formed by personal relationships that condensed into economic networks.Footnote 40 The First World War had caused a serious setback in business relations, not only for German companies, but also for many African merchants who traded with them. Hoping to revive former business relations was thus also in the interest of Liberian traders and migrant workers who had long-established relations with the Woermann company. Most German companies active in colonial trade – even those, like Woermann, so closely associated with the colonial project – neither commenced their existence with the establishment of the German Colonial Empire nor ended it with the loss of the colonies. The transnational networks and histories that transcended the chronology of the German Empire were starting points for reviving their business activities after the war.

The British colony of the Gold Coast became the most important region for the company economically. Here, C. Woermann profited from a rapidly growing export economy supplied by commodities such as the huge cocoa plantations run by African entrepreneurs.Footnote 41 By 1938, all of C. Woermann's overseas assets were located in West Africa, half of them on the Gold Coast.Footnote 42 Within a few years, the company had built up a factory network from Accra with up to fifty branch offices and stores mainly operated by African shopkeepers.Footnote 43 But this decentralised system proved to be costly and was soon abolished. The trading shops were concentrated in the most profitable places and German employees replaced African shopkeepers.

Neither in economic nor in social and cultural terms did the end of formal colonial rule mark the end of colonial racist practices. Racism was a formative aspect in the ‘rule of colonial difference’,Footnote 44 and it is especially in the racist practices on the ground that colonial continuities within imperial afterlives of German companies can be found. German employees of C. Woermann in the Gold Coast formed a community of the colonisers’ diaspora with their white British colleagues, which developed norms, values and culture that echoed those of the pre-war years.Footnote 45 This white diaspora's sense of belonging was fostered by the development of joint activities and mutual visits. These were welcome interruptions to the boredom that was a defining feature of everyday colonial life everywhere, but especially in the remote trading stations.Footnote 46 At the same time, the ubiquitous hospitality underlined the unity of Europeans against Africans and ‘bound Europeans together in an order of generalised reciprocity’.Footnote 47 It served communal integration and the recognition of belonging to the colonisers.

Labour conditions, too, reflected pre-existing colonial structures. The recruitment and employment of African workers was done in a collective way and followed the desire of the European colonisers to form ethnically uniform teams as far as possible. Ewe and Ga-Adangbe people were recruited to work in the shops; Mfantsefo people worked as ‘boys’ in the household; and Liberian Krumen were recruited to work in the stores of the ports.Footnote 48 In some cases, these professions may have reflected the preferences of African communities. Some, like the Krumen, exploited opportunities that allowed them not only to earn comparably higher wages but also increased their agency. This concentration of ethnic groups in some cases also led to greater solidarity within labour groups.Footnote 49 Even so, attempts to form ethnically homogeneous groups of workers clearly followed the notion of racist hierarchisation and colonial segregation. On the one hand, they strengthened the dichotomy between colonisers and colonised. On the other hand, they created internal differentiations within the category of the colonised, which made it easier to incorporate them into a racist labour regime. On a practical level, German merchants were (re)integrated into a colonial hierarchy without being part of a formal colonial power themselves. Occupying a liminal space within the colonial hierarchy, neither fully integrated nor completely excluded from British social circles, they were nonetheless (re)integrated into the colonial system. This (re)integration was facilitated by their inclusion in a racist scheme as white Europeans that granted them privileges beyond being part of the imperial state. Despite the loss of the colonies, German companies were – once again – conducting colonial business without colonies.

C. Woermann wanted not only to participate in the global colonial economy as a trading company again, but to return to the significant expansion of its role as a producer. In the mid-1920s, it tried to re-enter the plantation business in the former German colony of Cameroon.Footnote 50 After the Allied victory, Cameroon was partitioned between the United Kingdom and France, with France taking over the larger geographical share and the British ruling a strip bordering Nigeria, containing the large plantation area on Mount Cameroon. Cameroon had long been the centre of C. Woermann's business activities, at least since the colonial annexation in 1884. After the founding of the colonial empire, senior director Adolph Woermann had systematically expanded his business in the newly annexed colonies. In 1885 he had founded the plantation company Kamerun Land- und Plantagengesellschaft (KLPG), which became the nucleus of the colonial plantation economy in Cameroon.Footnote 51

One of the primary concerns of the KLPG was the so called ‘labour question’.Footnote 52 This referred to the difficulty colonial enterprises had in mobilising labour. The KLPG relied heavily on forced labourers, recruited by the colonial government to cultivate the plantations. While Liberian workers performed crucial tasks in loading and unloading the ships, they were considered far too expensive in the plantation economy. Forced labourers, who were captured as prisoners of war during violent ‘punitive expeditions’, suffered on the plantations not only from surveillance, harassment, and brutal corporal punishment by their employers, but also from lack of care and diseases due to inadequate hygienic facilities. This sometimes led to terrible mortality rates. In 1895, under Governor Jesko von Puttkamer, the systematic ‘Inwertsetzung’ (valorisation) of the colony had begun: by 1900, all the fertile land on Mount Cameroon had been given to plantation companies, while the Bakweri living there had been expelled. In 1906, C. Woermann had bought out the KLPG and renamed it ‘C. Woermann – Bimbia Pflanzung’, which was confiscated and expropriated in the course of the First World War.

The British colonial authorities, who administered the plantations on Mount Cameroon on an interim basis after the First World War, planned to privatise the plantations.Footnote 53 A first attempt in October 1922 to sell the plantations in an auction failed due to a lack of interest on the part of British bidders (German investors were excluded from this auction). The plantation manager Frank Evans, appointed by the British mandate administration, contacted the boards of the German plantation companies and developed a strategy for the buyback of the plantations. Under the umbrella of the German company ‘Fako-Pflanzungen GmbH’, founded for this purpose, German companies agreed to acquire the plantations as a whole and committed themselves not to bid independently at the auction. The German government supported the plan. The Foreign Office provided a loan of 7.5 million marks for the purchase and reconstruction of the plantations.Footnote 54

The plan was successful. In November 1924, the German plantation companies acquired the majority of the plantations at an auction in London for the extremely low price of 4.2 million marks. C. Woermann acquired two trading posts on Mount Cameroon and the Bimbia plantation for 103,000 marks.Footnote 55 The decision to re-engage with the plantation economy reflects a calculated effort to capitalise on the region's abundant natural resources, particularly in the face of growing market demand. It was driven by a ‘considerable interest’ in relaunching involvement in African agriculture, particularly in the palm oil sector, with the anticipation of its future expansion and the prospect of numerous business opportunities for those well-versed in the industry.Footnote 56

However, despite initial optimism, this venture ultimately faltered, standing in stark contrast to the resounding success of (re)established trade relations in the same region. As before the war, labour was the biggest problem of the plantation economy on Mount Cameroon. The British Mandate administration had officially abolished forced labour for private enterprises, creating a significant labour market for plantation workers. In this context, pre-war networks were important, and Africans who had previously been in the service of the plantation companies played significant roles in the recruitment of labour.Footnote 57 The British laissez-faire policy towards the plantation companies ensured that the social policy requirements of the League of Nations were simply ignored. By the end of the 1930s, when the British insisted on mandatory health and social policy standards in British Cameroon, C. Woermann had already given up the plantation business.

The Bimbia plantation did not remain in C. Woermann's possession for long. From the beginning, the plantation faced substantial economic challenges. As the plantation company had become a separate limited entity, it relied heavily on support from the German Reich to stay afloat. Despite receiving multiple loans, the company struggled due to generally weak profitability. A key factor contributing to this failure was that the harvests fell far short of pre-purchase expectations. This was because of structural changes in the plantation's output. Before the First World War, cocoa was the main product of the plantation, but a significant portion of these cocoa plants perished prior to the war. Consequently, the plantation opted to diversify its crops by introducing oil palm and rubber trees. The yields from these harvests fell far short of the estimates made before the plantation was purchased.Footnote 58 Furthermore, the income generated was substantially offset by the high expenses incurred for the care and maintenance of the new crops and wages for plantation workers.Footnote 59 Since 1928, the plantation had deteriorated to such an extent that Kurt Woermann engaged in negotiations with other companies regarding its acquisition. Initially, the Bimbia plantation ceased its own operations and leased its planting grounds to the West African Planting Society of Victoria (WAPV). In 1930 Woermann sold the entire company to the WAPV.Footnote 60 The failure of the plantation enterprise suggests that production, particularly in the form of raw resource extraction, is more susceptible to challenges stemming from state intervention and the complexities of labour management. Unlike trade, which may enjoy greater flexibility and autonomy from formal colonial rule, the plantation economy's heavy reliance on cheap labour and long-term investment made it more vulnerable to the constraints imposed by state policies and regulations. This illuminates the complex relationship between trade and production in the context of post-colonial conditions and emphasises the intricate interplay between economic activities and state intervention in shaping their respective trajectories.

Postcolonial Zombies: Eastern Europe as a New Space for Colonial Businesses

What C. Woermann had built up in the years following the First World War was wiped out by the world economic crisis that began in 1929. This had an immense impact on the European colonies and mandate territories in Africa due to the drop in prices, especially for tropical products.Footnote 61 Moreover, one of the political consequences of the Great Depression was the strengthening of colonial revisionism in Germany in general and in Hamburg in particular. This exacerbated economic struggles in Germany, fostering widespread frustration and fuelling nationalist sentiments seeking to restore Germany's imperial power. Amidst economic hardship, policymakers and the public saw colonial revisionism and imperial expansion as a means to (re)access resources and markets, while movements like the Nazi Party capitalised on discontent, using colonial revisionism to rally support for territorial expansion and racial supremacy. Following this movement, Kurt Woermann attempted to follow in his father's footsteps as a political merchant. In May 1929 he was appointed to the board of the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft (DKG or ‘German Colonial Society’), but he resigned in January 1931 because he apparently doubted that he would be able to advance his colonial agenda with the help of the DKG.Footnote 62

Woermann was an advocate of an expansive colonial ideology blended with elements of National Socialist ideology. He supported Germany's re-acquisition of colonies with a social-imperialist justification: German ‘colonisation in Africa’ would ‘alleviate the two most burning needs of the present, unemployment and the crisis of agriculture’.Footnote 63 Woermann, who had probably been a member of the NSDAP since 1929, advocated an imperialist policy that combined overseas colonial expansion with National Socialist settlement policy. Woermann emphasised not just the need for active German settlement in Africa but also endorsed Eastern settlement and the implementation of compulsory labour service. According to his vision, labour service represented the ‘urgent major national task’ that should temporarily overshadow African colonial policy until the Eastern settlement, or Ostsiedlung, gained momentum. But his ideas were rejected by the majority of Hamburg's merchants and colonial movement. Neither the DKG nor the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce considered it appropriate to join his calls. The leadership of the DKG around Theodor Seitz was hesitant about his demands and had reservations about an overly close alliance with the National Socialists. This ultimately led to Woermann's resignation from the board in 1931. Furthermore, in March of that year, the Chamber of Commerce informed him that further discussion of his ideas did not promise success.Footnote 64 While colonial revisionism was a central goal for Hamburg's economic circles in the early 1920s, it waned in influence from the mid-1920s onward. Although the Chamber of Commerce theoretically supported the idea of reclaiming the colonies, it appeared imprudent for those in charge to vigorously advocate for this demand in light of the geopolitical balance of power.

Instead, Woermann formed new alliances. He was part of a group of young Hamburg entrepreneurs, including figures like Emil Helfferich and Franz Heinrich Witthoefft, who, having backgrounds as colonial merchants, attempted to establish a partnership with National Socialism during the Weimar Republic, something that many older Wilhelminian-minded Hanseatic merchants rejected until 1933.Footnote 65 It became apparent that there was an increased willingness to collaborate with National Socialists, particularly evident among colonial entrepreneurs. Woermann, together with other Hamburg merchants such as Helfferich, Witthoefft and Karl Krogmann, signed the ‘Industrielleneingabe’ in which nineteen representatives of the German economy petitioned German president Paul von Hindenburg to make Adolf Hitler the German Chancellor on 19 November 1932.Footnote 66 The National Socialists’ seizure of power further nourished the hopes of colonial revisionists. Encouraged by opportunities arising from this new political configuration, Woermann now systematically sought to advance his combination of National Socialist settlement ideology and colonial expansionism through the colonial revisionist movement. Colonial revisionism, however, was not a central element of politics under National Socialism.Footnote 67 Instead, the locus of German colonial ambitions shifted to Eastern Europe.

Eastern Europe became a new colonial space for companies that had previously been active in overseas trade. With the beginning of the Second World War, German shipping was cut off from trade routes to Africa by the Allied blockade. The war brought uncertainty for many colonial companies. Goods that were to be exported overseas had been piling up in the warehouses of Hamburg since the beginning of the war. Kurt Woermann examined several strategies for the future operation of his business, including relocating the company to Spain in order to manage operations in Spanish Guinea from there.Footnote 68 Gradually, a strategic shift occurred, wherein companies like Woermann transitioned away from seeking opportunities to establish a presence in overseas markets during the war. Instead, they began to realign themselves within the framework of the National Socialist imperial agenda. In September 1939, Woermann recommended that goods that were to be exported overseas but had been piling up in the warehouses should be sold in Poland. He also noted that only ‘cheap, low-value “Negro articles”’ were suitable for this purpose, which could not be sold in ‘highly civilised’ countries.Footnote 69 By the spring of 1940, Kurt Woermann saw the establishment of branches of his company in the Generalgouvernement (General Government), the zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, as a commercial opportunity. In March 1940, he sought to obtain loans for the establishment of permanent branches in Poland.Footnote 70 After the destruction and expulsion of Jewish businesses and tradesmen, C. Woermann established a trading post in Krasnystaw in the district of Lublin as part of the ‘suffering overseas firms’.Footnote 71 As early as September 1940, thirty-two such overseas companies were operating in the Generalgouvernement as so-called ‘Kreisgroßhändler’ (district wholesalers) or as ‘Einsatzfirmen’ (operational firms).Footnote 72 Companies like C. Woermann or G. L. Gaiser were supposed to build up factory networks in Eastern Europe ‘analogous to their African factory business’.Footnote 73

The reorientation of geographical focus strategically aligned with the synthesis of National Socialist settlement policy in the East and pre-existing colonial ideologies advocated by Woermann prior to 1933. Initially, the ‘Osteinsatz’ (Eastern deployment) was supposed to serve as an interim solution until companies could reactivate their business in the overseas colonies. But the shift in the geographical focus of commercial activities fitted into the National Socialist strategy of conquering ‘Lebensraum im Osten’ (living space in the East) and was strategically pushed by Hamburg's economic politicians and National Socialists.Footnote 74 Consequently, Woermann and other colonial companies seamlessly integrated into the overarching Nazi imperial agenda.

The activities of Kurt Woermann, C. Woermann and other colonial enterprises from 1939 onwards are in this respect less an example of an imperial afterlife than of an updating and readjustment of a colonial practice and an imperial mindset under the aegis of National Socialist imperialism. This connection between colonialism and National Socialism is particularly significant when considering the war and occupation in Eastern Europe. It underscores that the ideology and practices of German colonialism did not simply vanish but rather persisted and were reconfigured within the Nazi regime. As such, the example of C. Woermann confirms a position advanced by Jürgen Zimmerer and others that there were indeed direct personal and organisational continuities and connections between the German colonial empire in Africa and National Socialist rule in Eastern Europe.Footnote 75

Conclusion

The study of a colonial business during and after a period of formal colonial rule demonstrates that economic entanglements need to be studied in a longer and more global perspective. This is the only way to understand imperial afterlives, not only as aftermaths, but as constitutive parts of German imperialism in their own right. The case of C. Woermann after 1919 reveals the diversity of colonial encounters in the economic as well as the political, social and cultural spheres, even without a formal German colonial empire.

After the First World War, C. Woermann initially concentrated on the reconstruction of the lost business empire. Besides Liberia and Spanish Guinea, the British colonies of the Gold Coast and Sierra Leone were the main focus. The Gold Coast in particular became the most important trading point for C. Woermann. Almost half of the company's total assets were invested in the British colony. At the same time, the company also tried to restart its plantation business in British Cameroon. But, after C. Woermann had bought back its Bimbia plantation in 1924, these plans failed and the plantation was sold in 1930. In the following years, senior director Kurt Woermann was a vocal advocate of the colonial revisionist movement and tried to combine colonial revisionism and National Socialism. Yet colonial revisionism was not an element of practical politics under National Socialism. Instead, from 1939 onwards, C. Woermann, together with other Hamburg overseas companies, concentrated on establishing trading posts in the occupied territories of Eastern Europe – a fact that suggests that there were not only imperial afterlives but also organisational continuities between colonialism and National Socialism, which were tied to a geographical reorientation of the imperial agenda.

C. Woermann's development between 1919 and 1945 exemplifies how important it was for transnationally operating companies to adapt to different political systems. Colonial legacies, concrete economic interests in African markets and the continued existence of a colonial world order thus had lasting impacts on the company's business policy and formed an important imperial afterlife of the German colonial empire beyond its formal end. A critical (post-)colonial business history approach contributes to a more nuanced understanding of these colonial and postcolonial entanglements and their economic, political, social and cultural implications. Furthermore, studying companies such as C. Woermann as entities that transcend political caesuras and how they reacted and adapted to the changing political landscape in Germany and the world – from their activities in the German colonial empire to conducting their business in the Nazi-occupied territories of Eastern Europe – highlights the historical continuum between colonialism and National Socialism. In conclusion, a critical (post-)colonial business history perspective enables a more comprehensive understanding of the interdependencies between economic and political systems and their social and cultural embeddedness.