In the heart of upscale Santiago, Chile, there is a four-story building that lies in ruins (see image 1). Fenced off and largely hidden from view, the building is dwarfed by the executive headquarters, financial conglomerates, luxurious apartments, and opulent malls that surround it. The ruin has a caved in roof, gutted interiors, empty window frames, and a partially overgrown façade that is marked by graffiti. It is an anomaly in this part of the city, a seeming relic that is out-of-step with the newer, meticulously maintained, and constantly upgraded structures that surround it. The ruin’s isolation is reinforced by a legal prohibition: no one is supposed to enter it. But although the building lies empty and decaying, it is a vitally important site, since its memory and property status are highly contested. This has included a basic conflict about whether the structure will remain or if it will be razed and the site redeveloped.

Image 1: The last building from the Villa San Luis, 2019 (Photo credit: Patrick O’Grady).

The ruin is one of the last buildings standing from the Villa San Luis, a massive, state-developed housing complex partially completed during the socialist presidency of Dr. Salvador Allende from 1970 to 1973. Under Allende, the complex housed former squatters. Many of these past residents, in addition to a group of activists, have been attempting to make the ruin an officially sanctioned memory site. They hope to refurbish it so that it can house a museum that would tell a history of the Villa San Luis. The museum would call attention to how the former squatters who lived in the Villa were forcibly removed from their homes by the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990), who came to power in a bloody coup d’état against Allende. Those evictions made way for the development of Nueva Las Condes, the complex that surrounds the ruin. This process exemplifies the kind of accumulation through dispossession that analysts have emphasized as central to processes of neoliberal urban restructuring.Footnote 1 In Nueva Las Condes, as in cities throughout the globe, this restructuring has been volatile, if highly profitable. The real estate values of Nueva Las Condes today are among the highest in all of South America.

For its many celebrants, Nueva Las Condes is a sign of Chile’s successful capitalist transformation. It is the kind of place that has led figures such as Sebastián Piñera, Chile’s right-wing president, to argue in October 2019 that Chile remained “an oasis of prosperity and stability” in Latin America. Such a comment reaffirmed the more than forty-year-old myth of Chile as a pioneering, successful model for the pro-free market reforms of neoliberalism that the dictatorship (in)famously implemented in the mid-1970s. Piñera’s comment, however, touched a nerve, and it soon became a rallying cry in protests that engulfed the country. In signs and chants, demonstrators signaled that Chile “was never an oasis” and that the protests were not about merely 30 pesos—the increase in transportation fare that had touched off the riots—but rather about thirty years of an incomplete, unjust transition to democracy after the dictatorship. As an integral part of their platform, protestors denounced how Chile generally continued to follow the neoliberal model.

As in these protests, memories about the dictatorship and its aftermath remain a touchstone for conflict and mobilization. Piñera’s government has generally sought to “close the box” on memories of dictatorial abuses, an important element in conservative reactions to the memory question stretching back to the late 1980s.Footnote 2 This is evident in the Villa San Luis. In June of 2019, through the National Monuments Board (el Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales), the government overturned a decision from two years earlier that permitted the ruin both to be preserved and to house the museum of the Villa, an initiative initially undertaken during the second center-left government of Michelle Bachelet (2014–2018).Footnote 3 The reversal was heavily criticized by those who sought to preserve the site, for whom the last remnant of the old complex held a potent symbolism: a haunting reminder of both the violent remaking of Chilean society during the neoliberal era and the paths not taken in Chilean history.

In June 2020, those who wish to memorialize the Villa San Luis reached an agreement with the owners of the site, the Real Estate Company President Riesco, to permit a museum to be built there. This, however, was only a partial victory. The Piñera government has still not decided whether the last building from the Villa will house the museum, since this depends on determining if the building is structurally sound. If the building is razed, the museum for the Villa will be housed in a new skyscraper, undercutting much of the grounds upon which the memory site would unsettle the contemporary cityscape and pro-neoliberal sensibilities.

The controversy over the Villa San Luis underscores critical avenues through which neoliberalism and its violences in Chile can be understood, contested, and critiqued. Activists seeking the memorialization of the Villa point to troubling forms of violence and injury that mark the turn to neoliberalism, directly linking dictatorial abuses to interconnected forms of inequitable capitalist and spatial development. Yet as this essay also develops, there are some surprising dynamics in the evolution of the Villa San Luis that have not received attention in efforts to memorialize the site. These include the fact that several hundred of Villa San Luis’ original occupants remained in their apartments until after the dictatorship. This omission is itself the kind of silence that can complicate narratives of neoliberalism. As a growing number of commentators have argued, neoliberalism is itself a troubled, “rascal” concept that can be all encompassing and suffer from overuse, teleology, and imprecision.Footnote 4

To avoid these problems, while also reaffirming the critical need to confront neoliberalism’s violence and its ongoing force, this essay maps out a history of the Villa San Luis that contextualizes both the memory and property struggles over it, with an emphasis on the latter. The dramatic ideological shifts in Chile’s governments have led to significant changes in property relations, from the relatively brief, limited project of socialism to the much longer-lasting, enveloping project of neoliberalism. Still, as this article will also stress, property relations contain more enduring, subtle dimensions, including how they can be attached to the status of buildings and the worthiness and legitimacy of political subjects who wish to possess them. Liberal ideologies and relations of property have been part and parcel of these dynamics. Exposing these elements of property can help us to better put the epochal changes integral to neoliberalism in their time and place. The trajectory of the Villa San Luis reveals how urban restructuring under neoliberalism has included violent forms of spatial reorganization and an interrelated expansion of finance capital tied to a commodified real estate market. Yet, it also underscores the deep hold that property relations have on political subjects generally, including how those who have been opposed to the kinds of urban restructuring that has taken place in the neoliberal era have sought to denounce it and combat it. Such opposition has placed certain constraints on market-oriented forms of neoliberal urban restructuring, such as when squatters remained in the Villa San Luis site throughout the dictatorship. Ultimately, paying attention to property’s trajectory in an iconic site such as the Villa San Luis helps in mapping out key historical contours of neoliberal urban restructuring, including not only its dominant characteristics but also its limits and counterpublics.

In developing this argument, this paper tells a history of the Villa San Luis, analyzing first how those who wish to memorialize the Villa seek to remember it. I do so primarily through a museum exhibit they held, which will form the basis for the museum they will have in Nueva Las Condes. The exhibit gives testimony to the violent evictions these former squatters suffered. It develops crucial insights into histories that have been elided and submerged, yet it also contains its own silences. In revealing the latter, this essay looks more closely at how property dynamics evolved in the Villa, including how they were themselves embedded in broader histories that predate the neoliberal era, in which squatters claimed a right to housing. This right has been of great consequence, providing the basis for the establishment of hundreds of permanent neighborhoods in the city and allowing some of the original residents in the Villa to stay there. Given this, it is important to recognize that the neoliberal city has been shaped by violent forms of dispossession, in addition to liberal property relations more broadly and the rights that subjects have been able to claim within them. To frame the entire discussion, the essay begins by developing an understanding of property that calls attention to its embedded entanglements and its consequential myths, including links between property and propriety.

Before proceeding, a word of caution: it is important to emphasize that the varied silences that enshroud the destruction of the Villa are far from equivalent. The kinds of forgetting that elide the mass eviction of the Villa’s original residents whitewash state-supported acts of accumulation through violent acts of dispossession. They are on an entirely different order of magnitude than certain gaps in the memorialization of the Villa San Luis. Still, the multiple memories and silences involved in the Villa provide fertile ground for an understanding of how neoliberalism and its property relations have evolved in Chile, a pioneering, key, and emblematic location for neoliberalism’s rise and extension.

Property’s entanglements and a deep history of neoliberalism

Many have possessed parts of the area that was the Villa San Luis, from low-income citizens asserting a right to housing to Chile’s wealthiest business firms. To varying degrees, legal contracts and the sovereign power of the state have backed such forms of possession, often in highly controversial ways. Since the widely publicized plans were announced to build the Villa in 1965 under a reformist, Christian Democratic government, the site has held an iconic status, something which has tied it to national patrimony and made it an emblem of Chile’s starkly different presidencies. Ideological conflict has animated struggles over who legitimately owns the Villa and what should happen to it. Such struggles have been intertwined with the intense transformations that are part and parcel of Chile’s historical path through socialist revolution and neoliberal reaction.

These struggles, however, have always taken place within property’s entanglements, the elements of which, especially when it comes to residence and landed real estate, are manifold and can be resistant to historical change. Property is more than a mere legal contract or a set of rights—it brings people, land, and/or things into relationship, in which the values and meanings given to each are interrelated and interact.Footnote 5 From this perspective, property is embedded in institutions, legal arrangements, and everyday practices and expectations.Footnote 6 It attaches to personal status, buildings, the production of space, and governing relations. Property thus has an elemental, intersectional hold.Footnote 7

There are also certain myths attached to property and this essay pays particular attention to one that resonates in liberal settings: property relations should provide a foundation for order, and they should unfold in ways considered just and proper.Footnote 8 This formulation evokes the classic link between property and propriety that John Locke so famously articulated. In this, Locke and his neoliberal intellectual descendants today—such as the influential Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, who advocates property-titling programs for squatters—hold a celebratory view of property. They claim that a well-governed private property regime provides the foundation for a just and prosperous social order.

Such a view has been rightly criticized, especially in relationship to homeownership.Footnote 9 It fails to recognize how homeownership can produce intense inequities and segregation, at the same time that it can rely on dangerous and illusory forms of finance, as in the lead up to the 2008 Great Recession. (Neo)liberals, moreover, presume that the link between property and propriety is a normative one, in which the kind of proper order and behavior that they see in property relations holds constant across different contexts. They also do not account for ideological conflict, other than to dismiss critiques of private property’s overarching social value.

If the link between property and propriety is a myth, it should not be dismissed as merely an impoverished social theory that serves as a defense for liberal capitalism. It is that, but it is also a generative, animating construct in liberal settings. In urban planning paradigms, for example, the link is one that contains an organizing principle about how the city should be ordered. The city should have property relations that are legible to state institutions and regulated by them, in which citizens occupy legally sanctioned residences. These citizens, in turn, should be worthy and legitimate subjects. But if citizens are defined thus, there is then an expectation that they should live in minimally acceptable living conditions. This has been an issue of transnational and trans-imperial significance since the “housing question” became a persistent and relatively ubiquitous governing concern in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 10 A central reason why housing has been an area of public debate is that so many governing subjects and citizens have not lived in conditions considered just or appropriate to their status. Such situations have led to calls for government action and provided a grounding for citizen activism and the claiming of rights in the realm of housing.

In Chile during the mid-twentieth century, as happened throughout Latin America and much of the Global South, housing conflicts became particularly enflamed. Large numbers of Chileans migrated to Santiago and housing was expensive and often exploitative for low-income populations, even as the government invested in ambitious new modernist housing projects such as the Villa San Luis.Footnote 11 At this time, squatting became much more ubiquitous, a situation generally cast as a crisis. There was a particularly powerful disjuncture at the time between property relations in the city and expectations of a well-ordered and minimally just city. While variable in time and context, such a disjuncture invariably exists, a dynamic that makes the link between property and propriety a conflictive and tense one.

As squatters became more common, governments often harshly repressed them. Still, responses to squatters have also involved significant reforms, even when squatters have not always been a priority in government spending. This has included the extension of state-subsidized housing. It has also meant accepting squatting as a means for gaining access to de facto and de jure forms of property, something that tends to build on notions of adverse possession and eminent domain, often changing property relations overall in the process. Ironically, this even became a tenet of certain neoliberal urban reforms, as with Hernando de Soto’s exhortations to legalize squatter settlements.

In general terms, then, the link between property and propriety provides the possibility for opening property regimes to forms of property that serve social interests, including permitting property to be acquired in extra-legal and informal ways, as in squatting and the seizure of land. The link can also provide a foundation for redistribution, welfare, and heritage. As I develop below, these elements were at play in efforts to build the Villa San Luis in the first place and they animate the idea that its last building should be a memory site. Throughout, property relations have provided sources of conflict, repression, and reform, since there has invariably been a disconnect between capitalist property relations and what various publics find as a just and proper order.

The link between property and propriety, in addition to the wide ranging, interconnected, and conflict-laden power dynamics that go into the making of property more broadly, underscore how elements in property relations can have an enduring quality to them, troubling conventional periodizations. Even in a country such as Chile that has experienced such radical breaks in its recent political history, sources of continuity have had historical force, including the relationship between property and propriety. Property regimes can be mapped vis-à-vis specific political projects, yet attentiveness to their ongoing entanglements, powers, and mystifications is necessary. This can serve to reveal key characteristics of an era, including the contours of actually existing forms of neoliberalism. Even in the extreme, pioneering case of Chile this form is variegated in relationship to others and at times more hybrid than one might suppose.Footnote 12 Still, if there are subtle and surprising characteristics to neoliberalism in Chile, there are also characteristics that are anything but, something that is evident in contemporary Nueva Las Condes and memories of dispossession in the Villa San Luis.

The past of the Villa san luis in the present

In the present, Chileans refer to the area of Santiago in which Nueva Las Condes is located as Sanhattan. Obviously, the area is quite different from its namesake, but the general overlap with Manhattan is noticeable as are some of its quintessential neoliberal features. Both areas feature monumental, iconic architectural sites, including the tallest building in their respective continents (see image 2). Nueva Las Condes includes a concentration of offices explicitly dedicated to or largely derived from finance capital and real estate values that are the highest in their national setting, affordable to only a tiny minority. Low-income service and construction workers build and maintain the area, generally commuting long distances to do so. Sanhattan also has an extensive, public-private security apparatus that plays a critical role in maintaining exclusions and privileges.

Image 2: Panorama of “Sanhattan,” 2016 (author’s photo).

In general terms, Nueva Las Condes is dominated by not only securitized enclosures and a highly stratified service sector, but also the pleasures, debts, deals, distinctions, styles, and profits of high-end capitalism in contemporary Chile. It thrives, in no small measure, because of the neoliberal turn in Chile. And like the Parisian arcades and boulevards that Walter Benjamin so famously explored following the restructuring of Paris during Napoleon III’s reign under Baron von Haussman, the fast-moving capitalist development of the area has produced evocative dream worlds of voluminous activity and commoditized pleasure and desire.Footnote 13 Such dynamics have been widespread in the neoliberal era and they all too easily crowd out the dislocations and violence of the past, including how the poor were displaced to make way for urban restructuring.Footnote 14 Yet, as Benjamin also emphasized in Paris, places of sanitized privilege, segregated order, forced exclusion, and often intoxicating attraction invariably rest on ruins and exploitation. Such undercurrents haunt social memories and the ruins themselves, making them active and dynamic, even as the memories can be pushed to the side, overlooked in the onrush of the present or silenced by powerful actors and forces.Footnote 15

For its part, the last building of the Villa San Luis has held a particular power to disrupt cityscapes of forgetting, an “eruption of memory” in an otherwise seemingly placid landscape in the heart of wealthy Santiago.Footnote 16 It makes an absence more palpably present, laying bare what is for many an open social wound. Its symbolism also points directly to the overlapping class and ideological divides that are of such consequence in Chile. The Villa would be the only memory site in upscale Santiago that points to abuses committed by the dictatorship, even as these kinds of memory sites have proliferated in the city more generally since the 1990s. The memory sites that do exist in wealthy Santiago only commemorate left-wing political violence or celebrated figures and events from the colonial and national past.Footnote 17

Memories of the Villa San Luis put a stain on the most powerful corporate and political interests in Chile. The ruins sit in front of the executive headquarters for LATAM, the largest airline in Latin America and one that resulted from a merger between LAN Chile and TAM Airlines of Brazil in 2010. President Piñera, with an estimated personal fortune of US $2.8 billion, owned 27 percent of LAN Chile’s stock shares in the 1990s and 2000s. While successfully running for his first term as president in 2010, he sold his shares, yet he did so as these stocks soared in value as the merger with TAM Airlines came through. He profited, but he also sought to disentangle himself from the improprieties that such large personal business holdings could mean for the presidency. Property’s attachments, especially in a site with such freighted symbolism as the Villa San Luis, are not so easily cast aside, though, and when Piñera returned to the presidency in 2018 he initiated the review that sought to overturn making the last building of the Villa a memory site.

The decision to do so upset the momentum that those who sought the site’s memorialization had gained through protesting and public advocacy. For several years, they had demonstrated in front of the site itself, helping to generate media stories, often with images of the ruin surrounded by Nueva Las Condes. Activists also took their protests elsewhere, including in social media campaigns, a documentary film, and demonstrations in downtown Santiago. After activists had successfully lobbied Bachelet’s government to memorialize the site, they held an exhibit at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Chile’s most prominent museum and research center that covers the abuses of the dictatorship. Importantly, the museum was inaugurated in 2010, during Bachelet’s first term (2006–2010). This was part of an ongoing project on the part of the post-dictatorship governments of the center-left (1990–2010, 2014–2018) to expose the magnitude of dictatorial violence, ensure that it would never happen again, and undergo forms of redress and reparations.Footnote 18

The exhibit included the materials that activists hope to present if the last building of the Villa San Luis becomes a museum. It was designed and curated by the two most prominent leaders of efforts to memorialize the site. This included a documentary filmmaker and Miguel Lawner, an architect who had played a crucial role in developing the Villa San Luis site as a high-ranking urban planner in the Allende government. With the onset of the dictatorship, Lawner had been detained, tortured, and sent into exile until 1984. The memorialization of the Villa was the culmination of a forty-five-year effort on Lawner’s part to recover a history of the site.

In the museum exhibit, he and his fellow curator laid out a damning critique of the Villa’s trajectory. In doing so, the exhibit sought to expand the definition of how Chileans had generally defined the issue of human rights in the post-dictatorship. The exhibit, for example, moved well beyond the focus of Chile’s two officially sanctioned truth commissions in 1991 and 2003, the first of which had documented cases of those disappeared and killed by the dictatorship and the second of which had detailed the use of torture. Instead of focusing on these kinds of abuses, the exhibit put the issue of dispossession front and center. As such, the exhibit called attention to both specific acts of dictatorial violence and the neoliberal urban restructuring that occurred during and after the dictatorship. This pushed the boundaries upon which officially sanctioned memories of the dictatorship and its human rights abuses have been built, providing an opening to affirm a more capacious understanding of these abuses than the one that has been dominant in Chile and beyond since the 1980s.Footnote 19

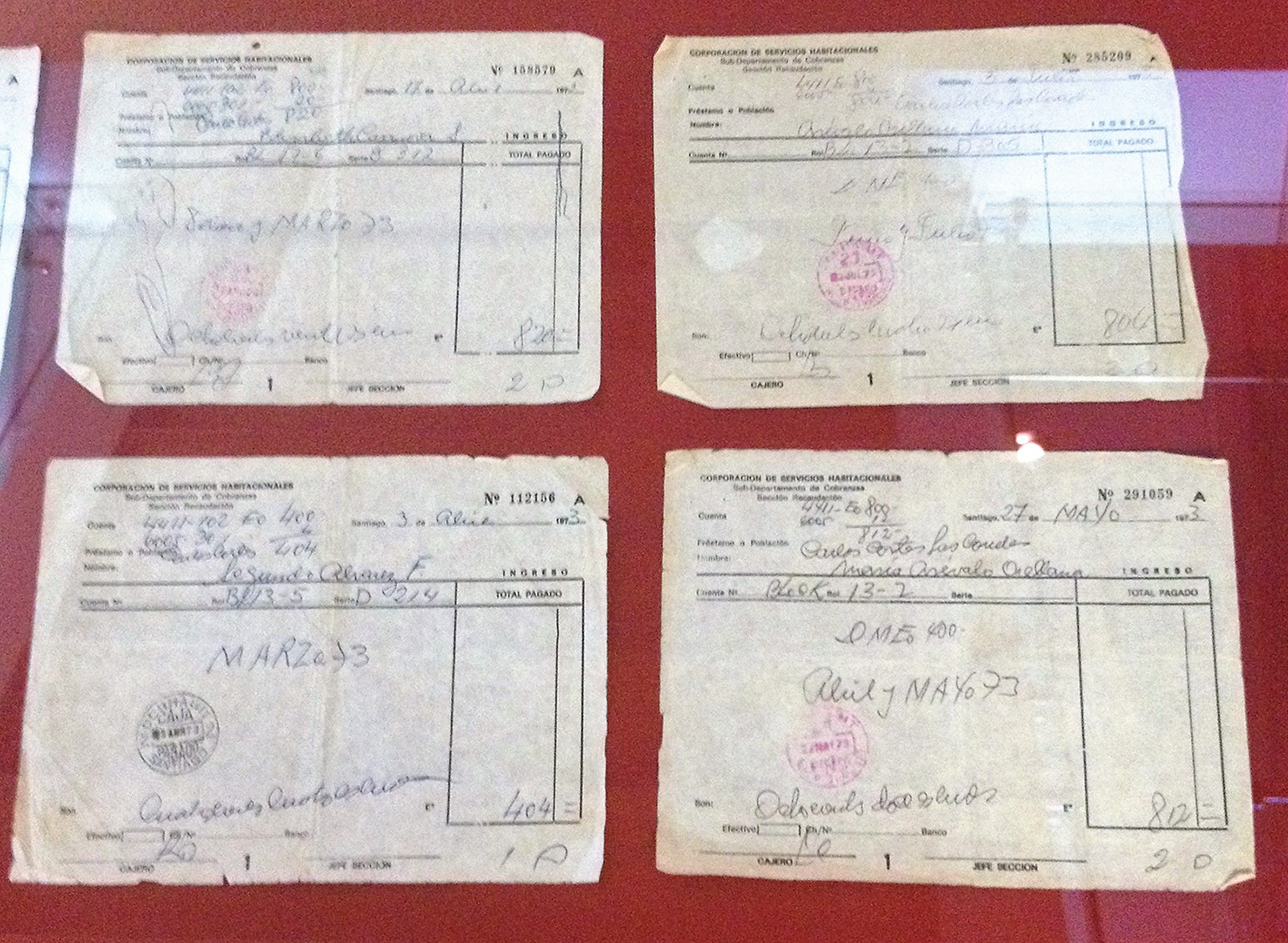

The exhibit began with a photograph of a woman who had been evicted from the Villa San Luis during the dictatorship taking part in a protest, holding a receipt of the dividend she had paid on her apartment. The accompanying text focused on the harshest moment of dispossession in the Villa San Luis, the period between 1975 and 1979 when soldiers evicted close to 5,000 residents from the complex. They often did so at gun point and, in humiliating fashion, they transported residents to low-income areas of the city in garbage trucks supplied by the Municipality of Las Condes.

In a documentary film, former residents affirmed just how unjust and injurious the process was, as losing possession of their homes marked a decisive, traumatic turn. “It was not a transfer (as they said), it was an eviction,” remarked one, while crying. “It’s sad, sad, they tore our lives apart.” “With the move,” said another, “everything that was yours and all that you had worked for was gone.”Footnote 20 The pain of this kind of dispossession is all the more acute for those who are barely able to gain a home in the first place. In interviews, former squatters narrate gaining access to legally sanctioned homes as a key turning point in their lives: “For me, receiving my home (in a subsidized housing program) was a truly beautiful dream. I’m the proudest, most pleased man about my home.” “I felt a great joy.… Human beings, when they feel that they possess something, they feel untouchable.” “It made me cry tears of blood (when I received the property title).… All of the sacrifice that I had undertaken was worth it in order to have the house. It was a house, as they say, to live decently.”Footnote 21 If squatters become homeowners and if they are dispossessed of their homes, they take part in life altering events, underscoring how crucial this form of property is for not only general well-being but also sociopolitical standing and understandings of the self.

The exhibit sought to make it clear that those evicted from the Villa were citizens who deserved their apartments. The eviction happened, the exhibit emphasized, “despite the fact that residents were paying dividends and were the legitimate owners of their homes.” To reinforce this point, a display in the exhibit showed four different receipts that residents had retained of their monthly payments on their apartments (see image 3). The dictatorship, meanwhile, had not only committed illegal evictions, but it also had military officers and their families move into the Villa, a clear, improper act of favoritism. Given these acts of violent dispossession and institutionalized corruption, the events in the Villa San Luis were, according to the exhibit, “a silenced history of human rights violations, in which there has neither been sanction for the guilty nor reparations for the victims.” What had occurred subsequently only made the situation worse. In 1991, a year into a new democratic government, the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism transferred the ownership of the site to the armed forces, of which Pinochet was still the head. This dubious legal maneuver possibly sought to placate Pinochet, just as the government released the first truth commission into the extra-judicial killings committed by the dictatorship.

Image 3: Receipts for monthly payments for apartments in the Villa San Luis, Exhibit at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, 2018 (Photo credit: Sigal Meirovich).

The armed forces subsequently sold most of the Villa to form the Nueva Las Condes site, profiting handsomely from the sale. The major initial investors in the Nueva Las Condes site would ultimately do so as well. These investors included, as the exhibit pointed out, Juan José Cueto, Sergio and Jorge Sarquis, Marcelo Zalaquett, and Alberto Kassis. Unlike in the case of the evictions, the exhibit did not directly accuse these investors of wrongdoing. Their names, however, are well known. Their investments underscored the central role that real estate development had played in Chile’s neoliberal urban restructuring, consolidating powerful business interests with significant links to the Pinochet government, the post-dictatorship democracy, and foreign investment. These investors were at the heads of businesses that had taken off during the neoliberal era: an export-oriented fishing company, a group that owned Chile’s largest casino chain, a family interest that (like President Piñera) held a significant share in LATAM airlines, a media empire, and a conglomerate that led the largest meat suppliers in Chile.Footnote 22 Such businesses had become more concentrated in the neoliberal era, benefitting from deregulation, the Pinochet regime’s attacks on organized labor, and the heightened financialization of capital, in which real estate development in places such as Nueva Las Condes has played such a prominent role.Footnote 23

Beyond its depiction of the evictions and their aftermath, the exhibit also provided a presentation of the Villa before the dictatorship. For the exhibit, this history started in 1972, during the second year of Allende’s presidency when residents moved in. Noting that the original plan had been to have a much larger housing complex, the exhibit underscored how only the first phase of the complex had been constructed and that more than five thousand residents had moved into 1,038 apartments. They had come from what the exhibit called “precarious settlements” in Las Condes itself. With the move, these low-income urban residents (known as pobladores in Chile) had finally achieved the “dream of having their own, dignified homes.”

The exhibit depicted a close relationship between the Allende government and residents. It featured an image of a meeting between pobladores who would move into the Villa and officials from Allende’s government, including Miguel Lawner. Furthermore, the exhibit noted, certain residents in the Villa had literally helped to build the site as construction workers. Pobladores, moreover, had decided to name the site the “Villa Ministro Carlos Cortés” after Allende’s first Minister of Housing and Urbanism, who had died in office in 1971. With the coup on 11 September 1973, the dictatorship renamed the site the Villa San Luis.

Overall, the exhibit developed a clear dividing line between the Villa San Luis and the Villa Ministro Carlos Cortés, between the dictatorship and the Allende government, between neoliberalism and socialism. Of course, there is good reason for doing so, but this kind of narrative structure can elide elements of what came before neoliberalism, a problem that often haunts the era’s periodization.Footnote 24 There is, in fact, a deeper, more entangled history of the Villa San Luis than the one depicted in the exhibit. Certain conflicts and unrealized dreams marked the Allende years. Popular mobilization, fueled by the notion that every Chilean had a right to housing, often conflicted with the Allende government’s plans. Ultimately, the issues of mass squatting and low-income housing have raised long-term tensions between the nature of justice, governance, property acquisition, sensibilities of order, and rights in the city. Squatter and low-income housing activism had been an issue of significant public scrutiny well before the Allende years, in no small measure because this kind of activism stood in contrast to the bold housing projects that modernist reformers had sought to implement. In Chile, no project was more ambitious than the Villa San Luis.

Modernist reform and the birth of the Villa San luis

In a widely covered ceremony, Eduardo Frei Montalva’s Christian Democratic government (1964–1970) announced plans for the construction of the Villa San Luis in 1965. In their public announcements, housing officials indicated that they planned to build a “model neighborhood,” creating a “new city center” of seventy thousand residents. Designed predominately for middle-and upper-middle-income residents, the project was also meant to include a limited amount of housing for lower-income groups. Residents would live in sixty-one towers of seventeen to twenty floors and forty buildings of four or five floors. The complex would include a civic and commercial center replete with a concert hall, post office, library, and hospital, in addition to several schools and parks (see image 4). As part of an effort to deepen forms of consumption and recreation, the project included stores for retail and groceries, in addition to a state-subsidized sports complex that the Universidad de Chile football club would develop. This would include a fifteen thousand-seat stadium, pools, soccer fields, and basketball and tennis courts. For planners, the initiative would provide public, healthy spaces and improve the city’s circulation.

Image 4: Architectural model for the Villa San Luis, 1968 (Auca 21 [1971]: 36).

The Villa San Luis project was ambitious and indicative of an effort to build a more integrated, accessible city. It was also firmly in line with the general, international embrace of modernist architecture and urban planning, initiatives that, at their headiest, promised to transcend a disordered and inequitable past.Footnote 25 For many modernist designers, these rational planning projects could also be put in practice in any national or ideological setting.Footnote 26 Yet, just as modernist plans generally gave inadequate attention to the complexities of city life (including their property dynamics), they also could not be free of specific ideological projects.Footnote 27 The Villa San Luis, in fact, was a part of Frei Montalva’s so-called “revolution in liberty,” a reform initiative that sought to expand state-led development projects and provide an alternative to the Cuban Revolution. This program received significant aid from the U.S.-led Alliance for Progress.Footnote 28

As a part of its efforts, the Frei Montalva government placed a great deal of emphasis on urban reform, forming the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (MINVU) in 1965 and granting nearly 25 percent of the national budget to related issues by the late 1960s.Footnote 29 Officials promised an attractive, rational, orderly, and hygienic city, in which Chileans could live with “dignity.”Footnote 30 Through significant government expenditures and proper planning, they sought to create a city of regulated, legally sanctioned homes, with clear property titles. Projects such as the Villa San Luis had this vision embedded within them: a well-ordered city would have a well-ordered property regime. If this was a taken-for-granted element of what a modern city should be, it was also a response to the fact that urban squatting and informal housing had rapidly increased at mid-century. Frei Montalva’s government promised to support the construction of 360,000 new housing units in the country from 1964–1970, including 120,000 low-income units, each of which would be well above previous highs.Footnote 31

In developing housing and new city spaces, officials made significant interventions in property relations, as the case of the Villa San Luis demonstrates. In 1965, the Corporation for Urban Improvement (CORMU), a body formed in 1952 and later subsumed into MINVU, expropriated the 10 square kilometer site that would become the Villa. The area had previously been an agricultural estate, but it now sat largely unoccupied and unused. This had been the case since the 1930s, when the estate’s owner had donated the land to a semi-private health charity organization. The owner’s children contested the donation in court, a long process that held the land in legal limbo until the 1960s.Footnote 32

The national government subsequently expropriated the site for three basic reasons: the land was contested, it was not under cultivation, and it could serve the general welfare. In doing so, the government drew on established legal precedents that became more robust over time.Footnote 33 In this, the Christian Democratic government, as an extension of the state-led development projects of mid-century, forged a property regime based primarily on private property, yet with significant exceptions and elements of redistribution. The government would change property relations by increasing the number of homeowners, granting the state direct control of more properties, and growing the housing stock.

The Villa San Luis project would have had a major impact on the development of Las Condes, one of Chile’s wealthiest municipalities. Since the turn of the century, Santiago’s elite had been abandoning the city’s downtown core as it became more congested and less exclusive, and Las Condes became a desirable location for them. As the wealthy moved in, the municipality established zoning laws and neighborhood covenant restrictions, fortifying rights to property that created spacious single-family homes in segregated environments and, increasingly at mid-century, high rise apartment complexes.Footnote 34 Still, the expansion of Las Condes came in fits and starts. There were both real estate booms and busts, while development could only happen with the extension of infrastructure services, a process that was not always forthcoming.

As elsewhere, Las Condes developed in ways that deviated radically from state plans and regulations, indicative of a common breach between a desired, proper order and property relations. Squatters, in fact, made major inroads in Las Condes, even if their residences remained effectively walled off from the municipality’s wealthy. Squatters established a series of neighborhoods in the area, especially in areas prone to flooding along the banks of the Mapocho River. Both the wealthy residents and officials in the municipal and national governments expressed deep concern about this process. For these Chileans, squatters were a dangerous, marginal group that threatened property laws and the value of real estate in Las Condes.

Reactions to squatters also broke down on ideological lines. Conservatives emphasized the importance of policing them, typically saying such things that if squatting and land seizures continued, this would return Chile to the “chaotic forces of the jungle.”Footnote 35 Centrist reformers, meanwhile, also viewed squatters as a major problem, but they sought their “development” through housing initiatives and support for neighborhood-based organizations. Housing activists and leftist groups, especially the Communist Party, often mobilized squatters, focusing on inadequate housing as a sign of capitalist failure and on squatter activism as a crucial location within which popular mobilization could be broadened. In their activism, however, leftists generally supported making squatters homeowners.Footnote 36 Yet from whatever perspective, the existence of mass squatting was indicative of an urban crisis, a sign that life was fundamentally out of order, an improper mismatch between what the city’s property relations ought to be and what they were. In this sense, links between property and propriety provided a crucial footing upon which ideological conflict, urban policing, and social mobilization unfolded.

Squatters clashed with police and suffered arrests, particularly when they began to take part in organized land seizures, a process that began in 1947 and increased throughout the 1960s. This included a number of well-publicized events in which squatters, including infants, died during police crackdowns. This culminated in a 1969 massacre in which police forces killed ten squatters in the Southern city of Puerto Montt, an event that resulted in a national scandal and a split among the Christian Democrats. It also ultimately forced the government to stop repressing urban land seizures, subsequently leading to a significant increase in their numbers.Footnote 37

Whether through land seizures or less dramatic, accretive forms of squatting in already established settlements, squatters increasingly gained a foothold in the city. They generally settled in areas on the outskirts of the city, in lands set aside for public development, or in precarious spaces that were not authorized for settlement. In spite of the risks, squatters were nonetheless increasingly successful at mobilizing sympathy for their cause and making the claim that they had a right to housing. In doing so, they drew on the same kinds of constitutional and legal precedent that had made the Villa San Luis possible. This included the ideas that property should serve the public interest and individuals who put land to productive use could continue to occupy it. If citizens—even disempowered, marginalized ones—made proper uses of property, they could often have it.

Coming into the Allende years, the government became even more accepting of squatter settlements, further transforming Chile’s property regime. Still, under both Frei Montalva and Allende, the government demanded that squatters fulfill the requirements of subsidized housing programs. The vast majority of squatters, in fact, and especially those involved in organized land seizures, had already been signed up in these programs, yet they had not received housing. The requirements included forms of savings, being part of a family, and acting as well-behaved neighbors who kept their houses clean and generally abstained from alcoholism, drug addiction, and domestic abuse.Footnote 38 Government appointed social workers and surveyors sought to verify these requirements, often in conjunction with the local leaders of squatter neighborhoods.Footnote 39 Following land seizures, squatters directly took part in the “autoconstruction” of their homes, neighborhoods, and infrastructure, a crucial action that literally turned squatters into city builders in Chile and elsewhere.Footnote 40 In Chile, squatters famously worked in teams through local democratic councils. Such processes could be fraught and open to transgression, yet they carried a particular force in how squatters claimed they had a right to housing and how they could establish their homes. In oral histories, former squatters emphasized how their neighborhoods had been well-organized and that residents lived according to moral standards and codes.Footnote 41 Here, appropriate kinds of behavior formed an integral part of claims to the rights of homeownership.

In seizing land and mobilizing, squatters ultimately ensured that housing would be a right of citizenship. They made it possible to become a homeowner through collective action and organized squatting. Many squatters developed forms of autonomy and governance at the grassroots, expanding the contours of citizen participation and democracy.Footnote 42 Squatters, though, were far from being a uniformly radical group, at the same time that they operated within certain liberal, governing relations. Certain attachments between property and propriety, for example, remained of importance, as squatters having savings, being part of families, and behaving in certain ways considered appropriate remained paramount in gaining a home.

At the level of the national government, the ambitious plans for housing and urban reform sought to make squatting unnecessary, instead creating cities of ordered and regulated property relations. Reform fell far short of this, however, in no small measure because it also had dark undersides, dynamics on display in the Villa San Luis. The vision of development in the Villa focused on a normative, middle class urban ideal, defined by high-rise living and modernist design. Special interests, meanwhile, weighed heavily. The powerful Chilean Chamber of Construction, a consortium of construction and real estate companies, lobbied for the Villa’s development. Mass projects such as the Villa, with limited amounts of low-income housing, were more lucrative than building housing complexes dedicated only to low-income recipients.Footnote 43 Indeed, the Frei Montalva government, fitting into a long-term pattern, promised to construct far more subsidized, low-income units than they actually built, instead providing more subsidies and state support to modernist and middle-income housing projects.

Ultimately, the redistributive benefits of this era primarily went to the Chilean middle classes and a more privileged sector of the working classes, but this did not include the poorest, a common tendency in Latin America at the time.Footnote 44 Low-income residents signed up in record numbers for housing subsidies, yet many did not receive them after years of waiting. This provided both motivation and justification for seizing land. Modernist projects such as the Villa San Luis, meanwhile, would not provide a solution to the housing problems faced by the urban poor, let alone the kinds of socio-political and spatial exclusions they suffered from.

The period of reform before Allende came to power consisted of significant, even insurgent openings in property relations, in which both the state and citizens could seize land in the name of the public good. Yet, if state-led, massive housing developments promised to transform cities and fully regulate property relations, they generally failed to do so. Squatters underscored these failures as they seized lands, further transforming property dynamics. They did so, however, based on the logic that they were proper, legitimate citizens who deserved homes of their own.

Socialist revolution

When Salvador Allende became president in 1970, construction of the Villa San Luis had just begun. With the Villa, as elsewhere, urban planners under Allende promised to go and, in a number of critical ways, went in radical new directions. They claimed that the city would “no longer be an expression of class.”Footnote 45 Adopting the motto “we’re going to move on up” (“vamos pa’ arriba”), they planned for the lower classes to live in apartment buildings. Planners undertook ambitious new architectural projects that included elements of “total” and “integrated” planning, while they also sought to complete projects already in place, if in altered form.Footnote 46 With unprecedented levels of spending in housing and urban reform, the Allende government initiated nearly eighty thousand new housing units in its first year, a record nearly two times over.Footnote 47

The Villa San Luis fit perfectly into this new direction, as the Allende government transformed the project into one that would exclusively house squatters from the surrounding area. The Socialist government sought to ensure that low-income residents could live in a wealthy municipality, in an area they had long lived in, closer to their jobs and social networks. The government also wanted to provide fully completed buildings that were integrated into existing city services.

At the same time, as the museum exhibit underscored, the government hoped to govern by building forms of solidarity between officials and popular groups. Many in the government had long been part of an activist left, including being sponsors of the land seizures. Carlos Cortés, the new Minister of Housing and Urbanism, was himself a former labor organizer. Nonetheless, the Minister now sought, in line with the government, a controlled, revolutionary process “from above,” in which planners would implement policies for the sake of the overall trajectory of the revolution and for the benefit of the lower classes. But peaceful cooperation between the socialist government and squatters was not altogether possible. Squatters, in addition to labor unions and agricultural workers, did not necessarily wait for the revolution that Allende and his planners had in mind. Instead, they seized factories, rural estates, and urban land at an unprecedented rate.Footnote 48 In Santiago, this included urban land seizures, the number of which had exploded in the months leading up to Allende’s inauguration and in the following year, in no small measure because the police stopped repressing them. Indeed, from 1967 to 1973, while precise numbers are difficult to gather, some four hundred thousand people in Santiago, about 14 percent of the population at the time, established homes through land seizures.Footnote 49

There were a number of seizures in Las Condes, precisely the kind that made officials worry. These seizures were generally sponsored by the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (the MIR), an activist, leftist group led by militant students not in Allende’s government coalition. While the MIR ostensibly sought revolution through any means possible, it ultimately found its footing working on causes that had long been a part of social organizing around everyday living conditions, including in housing.Footnote 50 In Las Condes, the MIR led land seizures as a means for organizing squatters and granting them a place to live in one of Chile’s most privileged areas. The seizures and the squatter settlements were highly controversial and received press coverage disproportionate to their numbers. Right-wing vigilante groups threatened the new settlements, leading to high-profile confrontations with residents.Footnote 51

The Allende government viewed these circumstances with increasing alarm, yet they refused to use force to break up the land seizures. In their new positions of authority in the Allende government, Carlos Cortés and Miguel Lawner urged pobladores to be patient and not seize land. The seizures, they argued, would galvanize the opposition, upset the government’s plans, cut into lands set aside for agriculture, and force the government to extend services beyond the existing city limits. The seizures could also be, as in Las Condes, a flashpoint for polarizing conflict.Footnote 52 Squatters and housing activists, however, were often unwilling to be patient. This was their moment, when they could realize the promises of “popular power,” seize possession of their own lands and ensure that they would have a right to housing.

The conflicts and tensions surrounding housing and squatting were present in the Villa San Luis. The museum exhibit made an oblique reference to this when it noted that the move into the Villa was part of a process that would help to prevent land seizures in Las Condes. The exhibit failed to mention that the squatters who were in line to occupy apartments came to the Villa’s grounds before it had been completed. These soon-to-be residents set up makeshift encampments to guard their apartments from other squatters who would occupy the buildings illegally, a situation that also played out in other new housing developments. In the Villa San Luis, this put pressure on the government to open many of the buildings in the development before they were fully completed, something that the Allende government ultimately agreed to do.Footnote 53 The new residents of the Villa forced the government to move faster than it wanted, a process that was relatively common with grassroots mobilization at the time.

On the day that the residents went into their new apartments, the government held a ceremony that Allende himself attended, celebrating the event as an indication of the government’s commitment to work in solidarity with pobladores. Unmentioned was that most of the new residents came to live in apartments that were not up to code. Given this, these residents could not gain legally sanctioned property titles, even as everyone occupied their apartments and paid monthly dividends.

Ultimately, as happened in the Villa San Luis, the Allende government’s policies of redistribution did not fit cleanly with mass democratic politics and popular action. Instead, pressure from below bedeviled Allende’s government, in which informal and extralegal forms of mobilization had long been an integral, if tense way of doing politics and settling the city.Footnote 54 The push for housing remained an unresolved issue. This was especially the case when major shortages began to occur in building materials, something which happened due to coordinated acts of sabotage between the CIA and domestic opponents of the government, the U.S. government’s economic sanctions, and the government’s own policies of increased spending.

Without question, the socialist revolution undertook a radical effort to remake the city, based on principals of equality, redistribution, and democratic participation. Both the Allende government and mobilized urban squatters did more than had ever been done to realize a right to housing for all. Yet the era of the socialist government was full of conflict and tension, while the revolution was itself limited and incomplete. As in the Villa San Luis, numerous housing developments and squatter settlements became physical instantiations of the unfinished project of socialism at the time of the coup. Many did not have titles to their properties. There were plans to make housing recipients and squatters property owners, but in many cases the socialist government had not yet been able to make this happen, especially since titles could only be granted if the property fit with the regulations of what a fully “urbanized” neighborhood was supposed to be.

Dictatorial reaction and the limits of neoliberal urbanization

The lack of clear and full property titles in the Villa San Luis was indicative of a time-encrusted, bureaucratic link between property and propriety, but under Allende, Villa San Luis residents had achieved a de facto status as property holders. From the perspective of the dictatorship, these residents were illegitimate squatters, a status that justified their expulsion.

The dictatorship undertook the evictions in a vicious, vindictive way: residents received less than a day’s notice they would have to leave, they were removed in the middle of the night, and they were relocated in garbage trucks. This formed a part of the reactionary politics of the dictatorship, including a demonization of the opposition and the reassertion of class distinctions and segregation in the city. A disproportionate number of the regime’s victims were pobladores and they were the only urban group to suffer whole-scale raids of their neighborhoods.Footnote 55 In fact, the removal of the residents from the Villa San Luis was part of a much larger process. The dictatorship evicted more than two hundred thousand pobladores living in squatter settlements or former squatter settlements from wealthier areas of Santiago to the urban periphery. This included twenty-one settlements in Las Condes.Footnote 56

Officially, the dictatorship did this for a number of reasons. It was part of policies designed to “eradicate extreme poverty” in the country, a poverty that was directly linked to the existence of squatter settlements.Footnote 57 Removing squatter settlements and other residents who lived in housing not fully sanctioned by the state was a way to more fully regulate property relations in the city, as those evicted were placed in housing that they had to pay for with the aid of subsidies on the outskirts of the city. This would overcome what officials termed the “chaotic,” “barbaric,” and “lawless” circumstances of the past. The regime sought to restore its sensibility of a proper order through the violence of evictions and heightened segregation.

As with neoliberals elsewhere, the regime revered homeownership: Pinochet often said that he wanted a country of “proprietors, not proletarians.” Though such a slogan seemed to extoll the virtues of a laissez-faire market based on fully regulated property relations, it elided just how actively the dictatorship shaped housing and segregation. The regime explicitly undertook the squatter removal programs in order to create municipalities in greater Santiago that would uniformly govern citizens of the same class.Footnote 58 The expulsion of the residents from the Villa San Luis was thus part and parcel of a process that (re)developed class segregation and a hierarchical order. It was a productive process that lay the foundation for real estate expansion and capitalist development in Las Condes and other wealthy areas.

Still, however, there were some limits to this, even in the Villa San Luis, including the five hundred pobladores who remained in their apartments (something that was, it is important to underscore, unmentioned in the museum exhibit). In a truly surreal turn of events, these residents became neighbors to the military officers and their families who moved into the Villa. Those who remained did not have full and clear titles, yet they did live in complexes that were now up to code and they continued to make payments on their apartments. At the same time, the last of the evictions took place in 1979 just as the dictatorship was undergoing a constricted, if important, democratic opening. The Vicariate of Solidarity, the human rights organization connected to the Catholic Church, documented and denounced the evictions. There were even national press reports that condemned the evictions as “exceptional,” “harsh,” “dehumanizing,” and “brutal.”Footnote 59 In the end, the dictatorship did not complete the evictions, representing a limit to its reactionary project.

Such a limit was part of a broader process, something which is important to develop in analyses of neoliberalism.Footnote 60 In Chile, the dictatorship even ultimately responded to the claims that pobladores made to housing as a right of citizenship, even if this happened slowly, reluctantly, and in piecemeal and conflictive fashion. Initially, the dictatorship significantly decreased spending on housing and made land seizures impossible. These policies, in addition to two major recessions and the creation of a more precarious, indebted, and insecure workforce, led to major housing shortages. Many pobladores quietly continued to arrive in existing squatter settlements, while others moved in with relatives and fictive kin, leading to packed, overcrowded housing. By the late 1970s, though, as the housing crisis worsened and thousands of squatter settlements still existed without formalization and property titles, the dictatorship began to make exceptions to its orthodox neoliberal policies. It both increased subsidies for residents to occupy low-income housing and underwent a massive property-titling program. These policies received significant support from institutions such as the World Bank and the Interamerican Development Bank and became models throughout the global South.Footnote 61

Neoliberals celebrated these programs for turning squatters into homeowners and for targeting government expenditures in poverty reduction. Yet in looking at Chile as a free-market model in housing they failed to recognize how much in these policies was not neoliberal at all. In implementing them, the dictatorship was responding to the long-term demand for housing, in addition to the ongoing activism of squatters. Despite years of intense repression against leftists and squatter activists, from 1982 to 1986 squatters once again took part in well-publicized, organized land seizures during the national protests. The dictatorship responded harshly, most infamously by attacking the largest squatter settlement established in Santiago during this period and torturing several of its leaders.Footnote 62 Nonetheless, the government did substantially increase spending on low-income housing, and they also permitted some squatters to remain and moved others to subsidized housing. In Santiago, more than fifty thousand squatters established their homes in this way.Footnote 63 This ultimately validated the notion that housing was a right of citizenship, something that the dictatorship had not made a part of its 1980 Constitution.Footnote 64

The villa san luis and housing in the post-dictatorship

In the period since the dictatorship, the response to the long-term demand for housing has been astonishing. Post-dictatorship governments spent more per capita on subsidized housing between 1990 and 2010 than any other nation on earth.Footnote 65 They also continued to pursue land titling programs for neighborhoods established by squatters. These policies certainly had neoliberal elements. They fulfilled, for example, “targeted” spending priorities, they were not set within an overall framework of wealth redistribution, and, as in Nueva Las Condes, they made real estate investments a central pillar of the financial and spatial expansion of capitalism. Yet these policies have also radically remade Santiago’s periphery, and the city has few remaining squatter settlements. (There has, however, been a recent increase in their numbers). This kind of spending on housing represents both a limit to an unfettered version of neoliberalism at the same time that it responds, at least in part, to squatters’ long-term demands. Claims to property and a right to housing played roles, however constricted, in shaping the urban environment in the neoliberal era.

Such claims have also mattered in the evolution of the Villa San Luis, making the process through which former squatters would be fully removed from the site slow and convoluted. Following the transfer of the Villa’s ownership to the Armed Forces in 1991 and the sale of the site to investors, many residents sold their apartments for approximately US$1,000.Footnote 66 The vast majority of the military officers did so, although they moved into some of the most highly valued subsidized housing elsewhere in the city. Several buildings in the Villa became abandoned, as the residents who remained were clustered in specific areas. These residents, in addition to many who had been evicted, increasingly took part in public demonstrations to assert their claims to the Villa and to seek forms of recognition and justice. Journalists increasingly came to report on the site as an emblem of how the dictatorship and neoliberalism had destroyed socialism and its projects.

Many of these observers made use of the site to criticize Chile’s urban direction. Critics had a particularly strong platform to do so when the Villa received national media attention in 1997, during the inauguration of the Nueva Las Condes Real Estate Development Project. The host of the ceremony was Joaquín Lavín, the Mayor of Las Condes who would be the right-wing presidential candidate in 1999. At the inauguration, Lavín celebrated the “strength and vitality of Chilean businesses” that had invested in Nueva Las Condes. The project would, he asserted, create a world-class residential, retail and office space development, providing a significant source of jobs. It would underscore Chile’s position as the so-called “Latin America Tiger,” a free market model. For Lavín, Chile in 1997 stood at the center of the millennial transcendence that neoliberalism appeared to offer, at its moment of greatest prestige and widest influence.Footnote 67

Lavín’s comments focused on the present and the future: vestiges from the past were to be left behind. The ceremony culminated in a climactic moment in which the past would be literally destroyed, as buildings from the Villa San Luis would be demolished. In the end, though, the buildings did not fall as planned; they had to be dynamited at a later date. This embarrassed Lavín and provided an opportunity for many to criticize the trajectory of housing in Santiago, especially those who sought to call attention to the dispossession of the Villa’s residents. In an interview, one displaced resident said, “The world is crazy. People destroy what is just fine and the new buildings that are made from plastic and cardboard fall on their own.”Footnote 68

This criticism referred to a series of scandals involving subsidized housing units, the number of which, as I have explained, had proliferated since the late 1980s. Several of these units had structural issues that led to flooding, and in one well-publicized case involving the Casas Copeva Company, the apartments could no longer be occupied. The government had not followed regulations in overseeing the site’s construction, while the owner of the company that built this housing was the brother of the Minister of Defense. This particular relationship underscored how housing developers generally had close connections to the government, since every Minister of Housing and Urbanism since after the Allende years had moved back and forth between the government and significant roles in the Chilean Chamber of Construction.Footnote 69

Social housing is often of a poor quality and is concentrated in poorer areas of the city. In the neoliberal era, low-income housing has generally been built ever further on the outskirts of Santiago, where land is cheaper and private contractors can better turn a profit on such housing (this latter feature is an important difference from the period before the coup). This housing is largely located in neighborhoods marked by poor urban services, violence, criminality, and poor relations with police. At the same time, pobladores have gained access to this housing while experiencing a harsh, neoliberal restructuring of the economy that led to deindustrialization and the making of a low-end wage market that is more flexible and precarious.Footnote 70 As such, pobladores have become more atomized and indebted.Footnote 71 As a foil to the Villa San Luis, the Casas Copeva housing development underscored how contemporary subsidized housing created impoverished living conditions and corruption was a part of its making. As such, urban property relations were unjust and improper—fundamentally out of order.

Former residents of the Villa San Luis and those resisting leaving it in the 1990s sought to call attention to these issues and the history of evictions in the Villa in public street demonstrations, with the support of a sympathetic congressional deputy. By 2000, these activists achieved an important victory: the original occupants who had stayed in the Villa received legal title to their apartments. In a decision granting the titles under the “Program for the Normalization of Irregular Tenancy,” the Ministry of National Properties indicated that the remaining residents in the Villa were people “of scarce economic resources, they have long occupied their buildings, (and) they have introduced improvements” to their residences.Footnote 72 These residents received rights to their properties based on principals of adverse possession, notions of the public good, and the fact the Villa now had been developed according to regulations. Similar logics were at play in the concurrent mass titling programs in place for squatter settlements. These programs sought to “normalize” property relations (the verb is revealing) and recognize residents’ need and their moral worth, the latter based largely on the care that they had shown in building their homes. When these conditions were in place, residents should be legally sanctioned homeowners, thus assuring a link between property and propriety.

While some residents received property titles in the Villa, the San Luis Real Estate Company also agreed to pay the former residents of the Villa reparations in response to the controversy over the site and the threat of lawsuits. The amount, however, was only around US$1,500 per claimant, much less than the booming value of the properties of Nueva Las Condes. For their part, the Municipality of Las Condes and the national government publicly declared that the indemnity was an agreement between private parties. They thus claimed that the issue was neither one of public concern nor was it relevant to how MINVU or the Armed Forces had acted as the owners of the site.Footnote 73 It certainly was not a part of the human rights violations committed by the dictatorship.

Even as claimants on the Villa gained some victories, the residents who remained faced intense harassment and pressure to leave. Real estate interests and developers, the military, the municipality of Las Condes, and MINVU all wanted to redevelop the buildings. Many became increasingly abandoned and fell into disuse and disrepair, including cut-offs of electricity and water. Meanwhile, the real estate companies began to offer more money to the remaining residents for their apartments, a process that led to conflicts as more agreed to sell. As time went on, the offering price rose dramatically. When the last of the original holdouts left in 2014, she did so not by being forcibly evicted, but by selling a two-bedroom, 450 square foot apartment for approximately US$750,000.Footnote 74

The end of the Villa had apparently, finally, arrived, the kind of complete reworking of the landscape that Marshall Berman, in his influential interpretation of Goethe’s Faust, argues is a prominent feature of modernity, capitalist or otherwise.Footnote 75 Yet just as the ghosts of the dead haunted Faust, so too the surface of the city could not be completely remade and wiped clean. Memory struggles about the injustices committed on the site, and the illegitimacy of its property status, live on.

Conclusion

In fundamental, unsettling ways, dictatorial violence and market forces tied to real estate and finance remade the site of the Villa San Luis along neoliberal lines. The thousands of individual pieces of commercial and residential real estate in Nueva Las Condes are now secure property sites, backed by the legal and sovereign powers of the state. The violent and legally dubious acts that made Nueva Las Condes possible do not upset the area’s contemporary property relations. The forces at play underscore not only how accumulation through dispossession and a “Haussmanization” of urban spatial relations have had historical force, but also how state-led repression and market-centered reforms undercut the political left. This was a crucial dynamic at play in Latin America, as reactionary violence overwhelmed revolutionary and reformist movements.Footnote 76 If neoliberalism generally has diverse origins and trajectories, it also gained force through state-directed acts of violence, as in Chile.Footnote 77

As the museum exhibit of the Villa San Luis stresses, any understanding of neoliberal restructuring should grapple with these forces and seek to come to grips with their haunted legacies. The squatters who became the residents of the Villa have made the dispossession and victimization they suffered a part of officially recognized national heritage, a significant achievement that broadens constricted understandings of human rights. These former residents are also part of a much larger history of squatting, in which squatters have gained access to homes and ensured that housing is a right, helping to transform settlement and property relations in the city. Historically, squatters gained access to property through extra-legal and non-market mechanisms. This has left a profound legacy on how Santiago has evolved, impacting its neoliberal trajectory. Even in the pioneering, emblematic case of Chile, neoliberalism did not unfold in a singular, inexorable way. Actually existing neoliberalism is diverse and variegated, far from operating in its ideal form.Footnote 78 In Chile, popular pressures forced a response that limited neoliberalism’s course, especially in ensuring that housing would remain, in practice, a right of citizenship.

As in the Villa San Luis, however, this outcome has had profound limits. Former squatters have generally come to live in segregated, insecure areas, where residents suffer from burdensome debt loads and high levels of unemployment and underemployment. Such dynamics have fueled both the discontent that led to a resurgent housing movement since 2011Footnote 79 and the social uprising that gained such force in October 2019. These overlapping protest movements have drawn a key source of support in low-income Santiago. For residents in these areas, housing and property titling has been far from being a panacea to impoverished living conditions and social exclusions.

This dynamic is especially important to point to in Chile, since the country has relatively few informal settlements, putting it on one end of a spectrum in countries in the Global South, part of the reason it became a neoliberal model in the first place. Still, this Chilean trajectory is emblematic of a larger pattern: there has also been a widespread process of property titling across much of the Global South in the neoliberal era. In Latin America, this has often included the formalization of land tenancy as a response to mass squatting.Footnote 80 Yet if Chile was once a model for these programs, the country’s current mass discontent offers a more cautionary tale.

At the same time, as this article has demonstrated, the Chilean case should never have been understood as singularly neoliberal in the first place. The settlement of the urban periphery in Santiago has been a more curious hybrid, the result of both neoliberal restructuring and combative forms of squatting and collective mobilization and claims to housing and property as rights of citizenship have been central. These claims have themselves been embedded in long-term, liberal dynamics in which notions of justice tied to propriety, personhood, subjectivity, and property holding have carried force.

In tracing property’s trajectory in the iconic site of the Villa San Luis, I have sought to map out key historical contours of neoliberalism in Chile itself, from its dominant characteristics to its limits and less-discussed features. If the Villa’s trajectory is a clear example of neoliberal urban restructuring, it is also a more complex palimpsest, underscoring how the city and its property relations are woven from multiple, interconnected, and often submerged strands.Footnote 81 Attention to these relations, including the power of their ongoing myths, can help to reveal this complexity. It can also help to put neoliberalism, with all of its haunted undersides and troubled effects, in its time and place.

For certain commentators on neoliberalism, its periodization should not even be attempted, since the category itself is all-encompassing, teleological, and loses specificity.Footnote 82 Some have countered that not using the category would rob contemporary publics of a powerful category through which to denounce and mobilize. This would certainly be the case in Chile, where neoliberalism and its forms of ruination remain of particular everyday significance. But holding on to neoliberalism as an analytical category is about more than simply supporting contemporary progressive forces. It is also about recognizing that the category has been alive and vital, a part of its own epoch, especially in countries such as Chile.Footnote 83 Transcending this epoch is paramount, yet such transcendence needs to be achieved through a recognition of neoliberalism’s dense entanglements and its occasionally surprising turns.

A focus on property provides a more embedded perspective and can thus be used in the service of a longue durée approach. In this, it is possible to analyze the specific terrain of neoliberalism, in which its unfolding force should not be underestimated, but in which its limits, contradictions, and counterpublics can better be revealed. Because such counterpublics are today ascendent, they will need to learn from the past, as questions about property’s acquisition and distribution, in addition to its myths, powerful interests, violent reworkings, and subjectivities, will invariably need to be confronted if a more just and equitable society is to be achieved. The unsettled memories of the Villa San Luis and its multiple forms of ruination, in addition to its contested property relations and varied silences, demand nothing less.