Harold Amateau could fit lots of things into a box neatly and efficiently. According to his daughter, everyone in the family turned to him when they needed help packing.Footnote 1 Amateau cultivated this talent as the owner of Caribbean Botanical Garden, a narrow, densely packed botánica, or religious goods store, that he opened in East Harlem at 80 East 115th Street in the 1930s. The tiny shop was stuffed with merchandise: medicinal herbs, candles, amulets, crucifixes, oils, incense, divination cards, statues of saints, and more (see image 1).

Image 1: Harold Amateau in front of Caribbean Botanical Garden, East Harlem, ca. 1930s. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

The size and meticulous organization of Caribbean Botanical Garden suited its owner, who was blind; it was also a prudent investment for an immigrant of modest means. But Amateau’s store was also stuffed with historical meaning. The botánica existed at the intersection of Eastern Mediterranean and Atlantic traditions and histories, and at the productive juncture of myriad religious, commercial, cultural, and healing practices.

Botánicas tend to be understood as local manifestations of an intricate, transatlantic Black, Caribbean, and Latinx religious, spiritual, and healing worlds.Footnote 2 Their shelves hold the herbal products, sacramental goods, ritual implements, and counseling that allow patrons of Italian, African, and Latin American Indigenous ancestries to practice folk Catholicism, herbalism, Hoodoo (also called “conjure”), Vodou, Santería, Espiritismo, Curanderismo, Òrìṣà worship, and other ethnomedical and spiritual systems.Footnote 3 Yet Amateau himself was an Eastern Mediterranean Jew from the Italian—and, in Amateau’s lifetime, Ottoman—island of Rhodes (today a part of Greece), and his botánica integrated, in addition to these varied practices, Sephardic and Eastern Mediterranean sources of inspiration. Caribbean Botanical Garden and other such shops run by Amateau and his relatives from the 1930s to the present day, including Nidia Botanical Garden, M. & A. Amateau Inc., and Original Products Botanica—all of New York City—and Rondo’s Luck Shop of Atlanta, introduce an unexpected Jewish and Eastern Mediterranean history to the botánica, and a multifarious spiritual, mercantile, and racial dimension to Jewish history.

Those who study Jews might be taken aback that a young Sephardic émigré would devote his professional life to serving as a healer and supplier to non-Jewish practitioners of alternative spirituality. Yet, my intention is not to frame Amateau’s story as a startling one, nor did Amateau, his clients, or his family view the family businesses as a study in contradictions. Indeed, to uncover the Jewish, Sephardic, and Mediterranean roots of Caribbean Botanical Garden serves to extend and reinforce the logic of botánicas, which “express an extraordinary layering of cultural experience.” It also complicates what we know of the complex racial terrain of early to mid-century East Harlem and modern Sephardic history.Footnote 4

Amateau’s story invites three insights, one into the history of the botánica, one into Jewish history, and the third into their intersection. The botánica has for the most part been represented as a product of transatlantic flows, but it also has an Eastern Mediterranean history, rooted in the soil of southeastern Europe and the island of Rhodes. Scholars of botánicas, already invested in the complex cultural and spiritual fusions that take shape within and through these institutions, will likely be amenable to this point, and it finds echo in histories of medicine and botany and the Atlantic world. Yet the specific argument needs a case study, which Amateau provides.Footnote 5

The second insight is that Jews, and not only Sephardic Jews, were prominent pioneering “spiritual merchants” of the United States, even if their cultural and material contribution to botánica history remains to be critically appraised.Footnote 6 Amateau’s history as a spiritual merchant compliments that of other Mediterranean and Middle Eastern (Muslim and Christian) émigré purveyors of spiritual goods like crucifixes and commodities like beli [Arab dance] and Oriental rugs, for which they served as “authenticators.”Footnote 7 An exploration of Jews’ movements into the spiritual wares trade builds upon scholarship that traces Jews’ (sometimes outsized) role in certain economic niches, including those like the botánica trade that catered to Black and other minority and immigrant consumers.Footnote 8 Though this case study finds echoes in other case studies, it is distinctive. It offers the first glimpse of Jews’ forgotten place within a fascinating entrepreneurial realm, it magnifies Sephardi stories in a conversation about Jews and commerce in the Americas that has been overwhelmingly Ashkenazi in its orientation, and it complicates a narrative of American ethnic dialogues conditioned by commerce that has privileged the Black-Jewish encounter over all others.

Finally, and relatedly, this article suggests that to explore the forgotten Jewish history of the botánica is to push at the boundaries of Jewish history, offering the field new spiritual, commercial, and racial contours. To explain this point, let us consider a lacerating review of Ilan Stavans’ compendium of Latin American Jewish literature, The Scroll and the Cross: 1,000 Years of Jewish-Hispanic Writing, written by Amateau’s nephew Richard Kostelanetz.Footnote 9 To highlight absences in Stavans’ collection, Kostelanetz invokes the world of his New York Sephardic family, whose messy branches included Amateau’s botánica, a place which sold “potent herbs appreciated mostly, if not only, by Latinos”; another relative’s olive-oil import operation; and yet another family member, a doctor, who catered predominantly to Puerto-Rican patients “because his English was insecure.”Footnote 10 These figures, so intimate to Kostelanetz’s orbit, he calls the “invisible Sephardim” of Stavans’ compendium, which skips from medieval Spain to modern Latin America, privileges the writing of Cryptro-Jews (though is also inclusive of Ashkenazi writers based in or from Latin America who write in Spanish), and altogether ellipsizes Sephardi and Mizrahi writers. “This Latin-American bias” writes Kostelanetz, “accounts for [Stavans’] failure to connect some critical dots about Jewish-Hispanic relations within the USA, especially in my home town.” Kostelanetz’s critique brings us back to the third ambition of this article, which is to focus not on Sephardic Jews’ invisibility in the history of the Americas (which has been ably explored by others) but on their very visibility in a series of racial and cultural and religious entanglements—particularly Jewish/Black/Latinx/Caribbean—that Caribbean Botanical Garden brings to the fore.Footnote 11

Harold Amateau’s personal and commercial peregrinations invite reflection on Sephardic Jews’ historic intimacy with spiritual healing and herbalism in southeastern Europe; émigré Sephardic Jews’ uneven dialogue with Black African men and women in Central and Southern Africa, which was informed by the violence and power imbalances wrought by colonialism; and, finally, the commercial, spiritual, racial, and cultural interplay furthered by Jewish-owned pharmacies and botánicas in New York City, Baltimore, Atlanta, Memphis, Charleston, Chicago, and Los Angeles and by Jewish spiritual merchants and their Caribbean, Latinx, and Black patrons. To unpack Amateau’s tightly packed shop in this fashion, we must first voyage through Sephardic history and to early twentieth-century Rhodes, and Central and Southern Africa, pausing to reflect upon the prevalence of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews as pharmacists and herbalists in the early to mid-twentieth-century United States, before finally returning to East Harlem, home of Caribbean Botanical Garden.

Island living, i

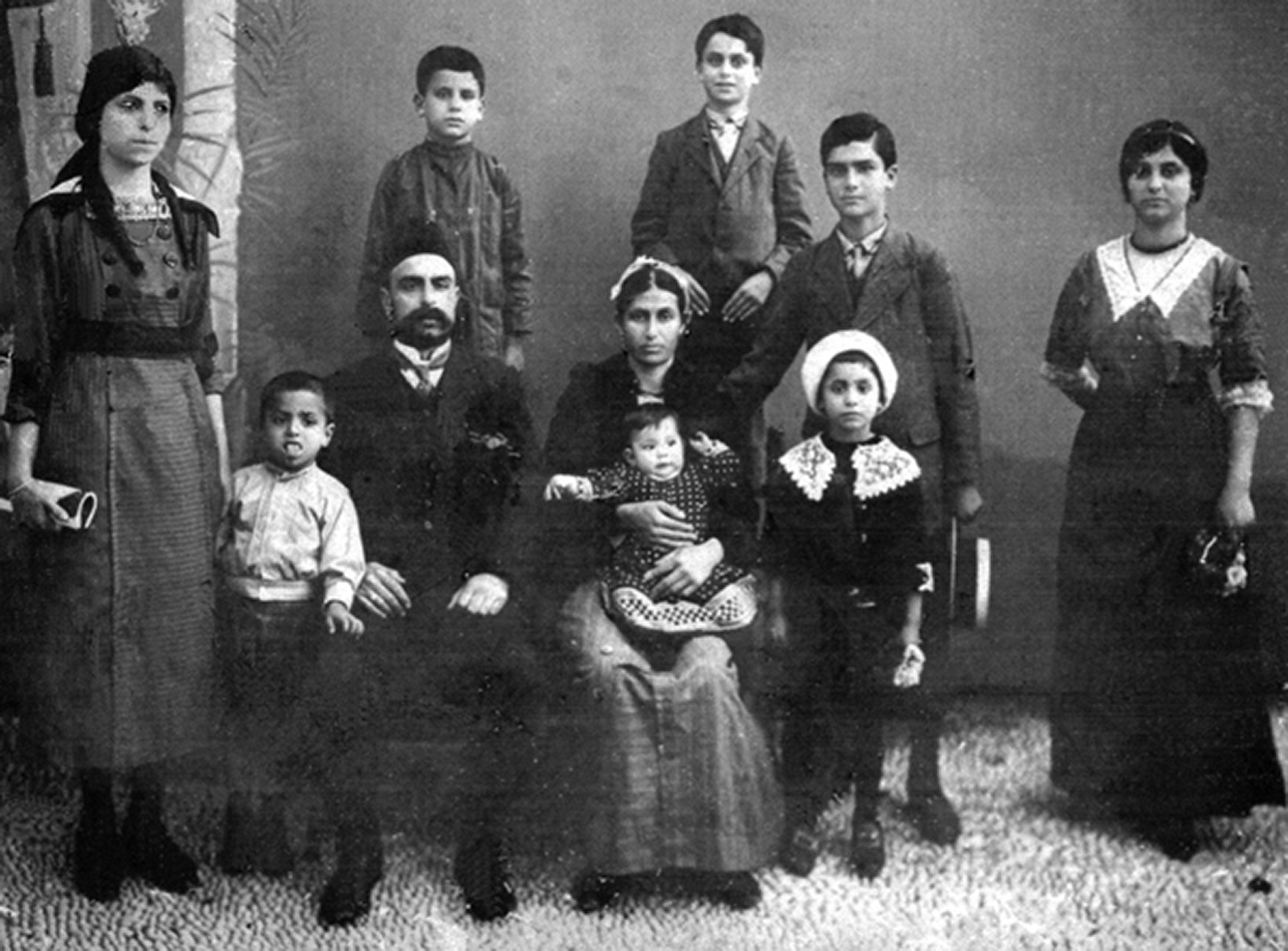

Harold Amateau was born Aron Amato, the second of nine children, on the largest of the Dodecanese islands, Rhodes (see image 2). Mountainous and encircled by ocean cliffs, just 18 kilometers south of the Turkish mainland, Rhodes had been under Italian control for but one year when Amato was born in 1913. For the prior four centuries, the island was Ottoman, and its Jews integrated into the Judeo-Spanish cultural world of Ottoman southeastern Europe.Footnote 12 Today, the island is Greek.

Image 2: Amato family, Rhodes, ca. 1917. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

Historically, Rhodes’ Jewish community was concentrated in the city of Rhodes, on the island’s northern tip. When Amato was born this community numbered 4,300 souls, most of them Judeo-Spanish (or Ladino) speakers and Sephardic—which is to say, descendants of the Jews exiled from Iberia in the late fifteenth century. One could tell the history of this community in political, legal, or economic terms, but these frames do not suit Amato’s story. To understand his trajectory, and the birth of Caribbean Botanical Garden, one must pin one’s sights on the natural and spiritual environment of his home island.

There was a lot of nature close at hand, and this is perhaps the most important point with which to begin. Rhodes during Amato’s youth was a fairly small town easily traversable by foot. The family lived in a two-story building made of local stone, with a capacious roof-top courtyard on which the family could gather. A second courtyard marked the entry to the home. In the Sephardic and Rhodesli tradition, these spaces were lined with flowerpots planted with roses, basil, rue, carnations, jasmine, and honeysuckle.Footnote 13

The rural edges of Rhodes were close at hand. Laura Varon (1926–?) remembers strolling from the town’s center to a small café on its outskirts on Shabbat afternoons during her adolescence. There, she would lose herself in the café’s smells, relish its lush garden, and “gaze for hours” at the magnificent pet peacocks that wandered about.Footnote 14 Further outside the town, the island was dense with flora and fauna. One could take a day trip to Villanova (today’s Paradeisi), home to the ruins of a castle built when the island was occupied by the Saint John Knights (1310–1522). The Amato family spent leisurely afternoons in outdoor cafes at Villanova, a camera capturing their frivolity. The Mediterranean offered refreshing waters, and swimming, too, was an intimate routine for the clan, as for so many other Jewish and non-Jewish residents of the island (see image 3).Footnote 15

Image 3: Swimming in the Mediterranean Sea, Rhodes; page from Harold Amateau/Aron Amato’s photo album. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

If the Jews of Rhodes lived close to nature, nature also provided them the tools for spiritual practices which fused Sephardic, Ottoman, Mediterranean, and Dodecanese traditions. Herbalism was common among Jews as well as non-Jews on the island, as throughout the region, and indeed herbalism had been important for centuries in the Ottoman realm. Most drugs dispensed by Ottoman medical practitioners in the early modern era were derived from plants, and Sephardic healing practices adhered to that general rule.Footnote 16 And though scientific medicine and synthetic drugs had gained legitimacy both in late Ottoman society and Italy by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, plants continued to be respected for their medicinal properties by healers and those in search of cures.Footnote 17 Basil, garlic, marjoram, mint mallow, chamomile, fennel, anise, parsley, cinnamon, cloves, coffee, and ruda; early twentieth-century Rhodeslis treasured all of these melezinas di kaza (or “medicines of the house” in Ladino) for their curative and magical powers.Footnote 18

Plants could not cure on their own. Their application adhered to a spiritual system, and within the Sephardic realm, mastery of this system tended to be the domain of women, especially older women, and also male healers (including rabbis), who were known as aprecantadores. Footnote 19 These traditions, which had roots in the early modern era, endured into the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when they attracted the interest of authors of ethnography, folklore, and memoirs, Rhodesli émigrés disproportionate among them.Footnote 20 These writers rightly understood that certain Sephardic folkways were becoming endangered at this time, threatened by the centrifugal pulls of emigration, politicization, and acculturation, as well as by the rise of scientific medicine, a field in which Jews were represented. Rebecca Amato Levy was among these chroniclers. In her memoir, Amato Levy recalls the work of her grandmother, La Prima Sara de Bohor Notrica, a noted healer born in Rhodes around 1850. “I remember as a child following her to the homes she was requested to visit, and being fascinated by what I heard and saw. With an air of confidence, she would enter the home of the sick as if she were a doctor. Her carriage was regal. She wore a long gown and robe (sayo and antari), a small hat (tokado) with the brooch in the center of her hat, and a gold belt and necklace.”Footnote 21 La Prima Sara de Bohor Notrica could cure all measure of ailments using mumia (a powder used by Muslim and Jewish healers, made from dried skin, including that of ostensible Egyptian mummies or the circumcised foreskin), water, sugar, special foods, and a wide repertoire of chants, rituals, and herbs.

These rituals, and the practice of herbalism, constituted one component of an elaborate system of popular medicine and spirituality that was not limited to Rhodes but typical of the Sephardic Mediterranean. This system blended Talmudic and Kabbalistic teachings, regional and local traditions, and included respect for the power of fortune tellers, magicians, healers, angels, demons, and interpreters of dreams, as well as spells, prayers, amulets, magical remedies, and powerful herbs. These “domains of innovation” existed (in the modern period as in earlier times) in tandem and dialogue with Jewish and non-Jewish religion and scientific medicine, such that the lines demarcating them were blurry.Footnote 22 In the Sephardic realm as elsewhere, there was endless interaction between organized religion, scientific medicine, popular religion, and folk medicine, with rabbis serving in all these domains as mystics, healers, and creators of kemeá (magical amulets).Footnote 23 Strikingly, while the lure of herbalism was strong across the Judeo-Spanish cultural zone of southeastern Europe and Anatolia, Rhodes was revered as the place where Sephardic “home medicine” reached its apex.Footnote 24

The Amato children—girls as well as boys—were educated in the local schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU), which were among hundreds of such schools established through the Mediterranean and Middle East by the Franco-Jewish philanthropy of the same name. The AIU aimed to “uplift” Middle Eastern Jewish girls and boys with the tools of a secular, French education and a thorough training in French. (By the time of Amato’s adolescence, Rhodes’ Jews had Italianized, too, and most of his generation became fluent in Italian.) An AIU education instilled in many Sephardic youth a sense—partly polemical, partly canny—that opportunity was linked to being connected beyond one’s community, whether through emigration or a connection to French culture or society.

Indeed, by the 1920s the Amatos were feeling the global economic downturn locally, with the small size of their island ever more constrictive of financial opportunities for the young.Footnote 25 Like so many families on Rhodes, the Amato children began to emigrate in various directions—to France, the United States, Egypt, the Belgian Congo, British-controlled Southern Rhodesia, and beyond. Aron Amato’s turn came in 1928 when, at the age of fifteen, he followed his eldest sister Rebecca to Central Africa, a destination that had absorbed a steady stream of young Jewish, Rhodesli men and women since the early years of the century. Amato had recently graduated from the AIU lycée, and his departure was marked in a flurry of photographs taken, one speculates, with a new camera purchased for the occasion.

A Colonial Sojourn

Amato’s sister Rebecca (née Amato) Piha had made her way to Southern Africa via Egypt, where she married. Once in the region, she lived among an émigré community of Rhodesli Jews who established themselves in Southern and Central Africa. In the Belgian Congo (later Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), these Jews settled in towns along the Port Francqui-Elizabethville (now Ilebo-Lubumbashi) rail line, including Luluabourg (now Kananga), Kamina, Luputa, Matadi, and in the cities of Elizabethville and Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). Other Rhodesli Jewish émigrés settled in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in small settlements such as Que Que, Gatooma, Selukwe, and especially Salisbury (now Harare).Footnote 26

Members of this community occupied a complex place within the colonial racial and economic hierarchy. On one hand, they joined a class of white settler colonialists whose skin color, class, and legal status gave them extraordinary and unfair advantage within the colonial system they helped impose over local, Black African women, men, and families.Footnote 27 This is immediately apparent in photographs Amato took of and with his family. The extended family, immaculately dressed in the European vogue (meticulously cleaned, starched, ironed, and blindingly white), are represented vacationing in their Buick touring car and luxuriating over meals in homes equipped with imported furniture and household objects such as decorative lace, elaborate glassware, and a piano. Occasionally Black African men, women, and children who appear to be domestic workers, drivers, and shop assistants are featured, as in one photograph Amato took of two of his nephews, pinning to it an infelicitous caption identifying “Simon, Isaac, and their Blacks [Simon, Isaac, et ses nègres].”Footnote 28

Yet Amato, like other young Rhodesli Jews who moved to Central and Southern Africa, did not (and was not entirely allowed) to emulate white, non-Jewish Europeans in his professional choices, for certain doors were closed even to the Jewish colonial elite.Footnote 29 Without access to the professions or colonial bureaucracy, many young Sephardim in these regions staffed or opened trading shops situated along rail lines and near mines that catered to a Black African buying public. Lebanese merchants occupied the same niche, and were the main competitors of Sephardic shop owners in the region.Footnote 30 Amato helped run his brother-in-law’s store and bakery in Gatoona and seems to have had something to do with a family-run store in Norton and another near the Turkois gold mines. He subsequently opened a store of his own in Jenkinstown, a location in southern Rhodesia which acquired a postal address in 1923 (see images 4a and 4b).Footnote 31 These shops tended to be simple, one-story, brick, and without signage, with an outhouse behind and a small temporary bedroom for their owner next door.

Image 4a: Aron Amato’s shop in Jenkinstown, Southern Rhodesia, ca. 1928, with unidentified man. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

Image 4b: Family-owned store in Norton (Chivero), Southern Rhodesia, ca. 1928. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

The commercial relationship fostered by these shops did not alter the racial status of Amato or Rhodesli Jews writ large. Undoubtedly, Rhodesli Jews in Central and Southern Africa reaped the distressing advantages of settler colonialism. And yet, running a shop that catered to Black customers also rendered diasporic merchants like Amato intermediaries in the colonial marketplace—what Andrew Arsen has called (in reference to the Lebanese mercantile community) “interlopers of empire.”Footnote 32 Certainly it placed them in closer proximity to Black African men and women than was experienced by many white Europeans, notwithstanding the fact that this proximity was contingent on the colonial marketplace.Footnote 33 Amato’s daughter remembers that when her father eventually left southern Africa, first for Turkey and then the United States, his knowledge of “Swahili” stayed with him. Whether Amato in fact communicated with his patrons in pigeon Swahili or Kituba or Lingala (in the Belgian Congo) or in Chewa, Chibarwe, Kalanga, Koisan, or any of the many other languages spoken in Rhodesia, the point is that he does appear to have had a linguistic and commercial relationship with the Black African women and men who patronized his store.

These relationships bore themselves out on the shop floor. Like any budding, entrepreneurial merchant, Amato stocked his store with merchandise he knew his consumers would buy: fabric, zippers, buttons, suits and hats; cooking pots, canned goods, biscuits, and grains; small suitcases and tires; cooking and motor oil. Did this stock include spiritual, herbal, or medicinal wares such as Amato would come to peddle in New York City, or even objects like minkisi [fetishes], which might have appealed to clients in or from the KiKongo cultural area?Footnote 34 While we do not know the answer, we can conclude that Amato’s experience in Central and Southern Africa lent him transferrable skills as a merchant and cross-cultural broker.Footnote 35 He would subsequently transfer these skills, and possibly knowledge of spiritual wares as well, to East Harlem. With him voyaged the mystique of having lived and worked in Africa, birthplace of religious and healing practices revered by many of his future African American, Caribbean, and Latinx patrons.

island living, ii

Aron Amato made his way to New York City under the newly adopted name Harold Amateau (by which I will refer to him from this point onwards) in 1933 after spending roughly eight months recovering from malaria with family in Istanbul. This trajectory allowed Amateau to join a substantial wave of Sephardic migration to North America.Footnote 36 New York was a logical choice from a familial standpoint, for by now all of Amateau’s siblings—save for Rebecca, the sister he left behind in Salisbury—were living in the city, as were Amateau’s parents.

Amateau joined his extended family in Queens. Had the family wished to join a dense Ottoman Jewish émigré community, Harlem or the Lower East Side would have been a more obvious choice. When the initial members of the Amateau family moved to New York City sometime in the first two decades of the century, the Sephardic kolonia [colony] of Harlem, then concentrated between 110th and 125th and Park and Lenox Avenues, was home to upwards of twenty thousand Sephardic Jews, roughly half of the city’s Sephardic population.Footnote 37 At least some of these Jews chose Harlem as a place of business or their neighborhood of choice because, being native speakers of Judeo-Spanish, they felt at ease with Spanish-speaking neighbors. This is one reason that Harlem was by 1925 as much of a magnet for the city’s Sephardim as was the immigrant-dense Lower East Side.Footnote 38 Caribbean Botanical Garden would open squarely in the midst of the kolonia, though at a time when most Sephardic Jews were abandoning Harlem for the Bronx.Footnote 39 The Amateaus, too, initially settled in the Bronx, but soon gravitated towards Queens’ whiter (indeed, racially restrictive), spacious North Shore, where they could purchase the borough’s affordable homes with gardens designed for lower middle- and working-class families, many Italians among them.Footnote 40

The Amateau home in the Bayside neighborhood of Queens boasted a garden dense with medicinal herbs and flowers raised by Amateau’s mother Rachel Amateau (née Capeluto). Under her green thumb, roses grew to 6 feet, and when they flowered Rachel Amateau candied their petals; she also preserved the rinds of the oranges and lemons that flourished in her verdant yard. There were grapes, mint, thyme, gardenias, and ruda. Remembers Micaela Amateau Amato, Amateau’s daughter, the garden was the family’s medicine cabinet, as well as its grocery store and refrigerator.Footnote 41 This space also provided the raw ingredients for Caribbean Botanical Gardens’ unique concoctions, a portion of which were prepared by Amateau’s mother.

Here, in this verdant garden in Bayside, the chapters of our story converge. The Rhodesli Jews’ historic embrace of plants and herbalism fused with Amateau’s experience as a cross-cultural trader in Central and Southern Africa and transplanted them to the multi-cultural environment of New York City, the nursery for Caribbean Botanical Garden. The store opened in the predominantly Black/Latinx/Caribbean East Harlem in the early to mid-1930s.

Whether Amateau was aware of it or not, there were a good number of Jews in or on the edges of the spiritual wares business at the time, most of them working and living in the American south and catering to Black consumers. Many early botánicas were little more than repurposed drugstores or pharmacies that came to stock spiritual cures or the “materia médica” of Hoodoo at the behest of Black patrons. Given the prominence of immigrant Jews as pharmacists and drugstore owners in Europe, the United States, and Southern Africa, and the related barrier that at that time kept American Jewish students from entering medical school (and other professional schools), it is no surprise that such shops were frequently Jewish owned.Footnote 42 This was true of Harry’s Occult Shop, founded in Philadelphia in 1917 by Russian Jewish immigrant Harry Seligman. As Philadelphia’s Black community swelled during the Great Migration, Seligman encountered customers requesting powders and oils unfamiliar to him. He began to research, sell, and produce spiritual products under his own label, eventually transforming his modest pharmacy into an occult institution.Footnote 43

Joseph Meyer was the main supplier of bulk herbs in early to mid-twentieth-century America, through his company Indiana Botanic Gardens, founded in 1910 and located in Hamond, Indiana. He was also Jewish, an immigrant from Germany, and responsible for publishing The Herbalist, a volume which has since seen at least seventeen reprintings.Footnote 44 Meyer’s chatty, informative catalogue featured detailed instructions on the uses of medicinal and magical herbs, leaves, seeds, roots, and flowers such as High John the Conqueror Root, Adam and Eve Root, Dragons Blood, Grains of Paradise, and Stumbul Root. In both catalogues and book, Meyer cannily hedged his bets, catering to an audience of white consumers of herbs and herbal derivatives and spiritual practitioners of color at the selfsame time.Footnote 45 Like so many of the businesses described here, Meyer’s passed through the generations: after his death in 1950, his grandson Clarence Meyer gathered his grandfather’s unpublished work for posthumous publication. By his own death at ninety-four, in 1997, Clarence himself had written nine books on folk medicine and herbalism.Footnote 46

Seligman and Meyer were joined in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s by other Jewish merchants who operated squarely within or on the fluid edges of the spiritual wares trade, catering primarily to Black, Latinx, and Caribbean clients.Footnote 47 The immigrant Hungarian Jewish chemist Morton Neumann of Chicago would prove the most powerful of the lot. Neumann’s Lucky Brown Cosmetics, created in 1926, became among the most important purveyors of Black beauty products in the country.Footnote 48 Working with his wife Rose, Neumann developed an expansive mail-order catalog that included lotions, creams, incense, skin lighteners that commodified colorism, and magical cures like “Follow Me Boy” sachet powder and “Kiss me Now” perfume. Sales were buoyed when Neumann began collaborating with the immensely talented Black graphic artist Charles C. Dawson (image 5).Footnote 49

Image 5: Advertisement for Sweet Georgia Brown Face Powder by Valmor, 1946. Advertisement courtesy of Made in Chicago Museum.

Other Jewish purveyors of spiritual wares include Eleanor and Theodore Blum, who operated Hy-Test Drugstore on Chicago’s South Side. The Charleston Cut-Rate Drugstore, opened in 1936 by David Epstein, served Charleston for almost fifty years. In Memphis, Tennessee, Joseph Menke and Morris Shapiro co-owned Lucky Heart Cosmetics and Spiritual Supplies. LeRue Marx, also of Memphis, produced Hoyt’s cologne. Marcus Menke founded and ran Clover Horn Company in Baltimore. Occult publisher Joseph W. Kay (also known as Joseph Spitalnik) founded Empire Publishing and Dorene Publishing, while “Mikhail Strabo” (Sydney J. Rosenfeld Steiner) owned Guidance House, a publisher of books on Hoodoo and Spiritualism.Footnote 50 Jews did not have a corner on the spiritual wares market—Caribbean Botanical Garden, for example, clutched the commercial coattails of Guatemalan-born Alberto Rendon’s West Indies Botanical Garden—but their prominence is noteworthy, nonetheless.

In time, the world of Jewish spiritual merchants came to be crosscut by collaboration and competition. But there is little reason to believe that Amateau was aware of or connected to this early network of peers, even if he relied on Meyer’s influential guides to herbalism. Relative to some of the aforementioned commercial powerhouses, Amateau’s Caribbean Botanical Garden was a tiny shop, and a neighborhood shop. According to family lore, the small size of the operation resonated with customers, who found it private and inviting. Caribbean Botanical Garden’s bilingual Spanish/English signage tempted shoppers with the promise of “books, herbs, oils, and roots.” Candles, saintly statues and portraits, and Tarot of Òrìṣà cards were visible in the window, along with miscellaneous bottles of oils. Inside, one could find supplies for the practice of folk Catholicism, Espiritismo, African American Hoodoo, and, in time, Santería/Ocha. In the store’s far back, Amateau had a station for private consultations; for, like most botánicas, Caribbean Botanical Garden had two sections, each with its own spiritual and commercial quality. The more spacious front of the store foregrounded merchandise for sale and the spiritual traditions catered to within. The back, by contrast, provided an intimate space for the owner to prepare remedies and advise clients.Footnote 51

Though it has proven impossible to obtain testimonials of Amateau’s patrons, we can learn about them and their view of Amateau through a variety of sources and perspectives. According to Amateau’s daughter Micaela Amateau Amato (also known as Michele Amateau), her father’s diverse patrons shared their “miseries, griefs, and joys” with her father, and accepted him as a powerful healer in his own right. “I remember during the 1950s,” she has recalled, “I would go with him during the summer, spent hours in the store…. He would sit for hours (it seemed) in his office, in the back of store, talking very intimately with different clients—Catholic, I don’t know what else. He was talking about their personal lives and giving them herbs and powders that would help them heal. I think it wasn’t just physical healing.…”Footnote 52 Amateau’s relationship with his clients was not merely commercial—he was, at least per his daughter’s account, accepted as a healer, a confidant, and an authority.Footnote 53 Like so many other botánicas, Amateau’s filled a niche for patrons who might not have trusted or been able to afford or access a licensed physician.Footnote 54

It is likely that Amateau’s blindness was considered a mark of promise, as the myth of the blind prophet or healer whose lack of sight only sharpens his vision is an ancient and potent one in folk Catholicism, and for followers of the Gullah religion and practitioners of Hoodoo and Vodou. It is also possible that Amateau’s Jewishness contributed to his success. Elizabeth McAlister has ably explored the long history of Afro-Haitian practitioners of Vodou (and their iconic musical parades, Raras) enacting “the Jew” either as a subject of demonization or a mystical ancestor.Footnote 55 Nor can we exclude the possibility that as a Jew and an “Oriental” Amateau commanded authority as a “money maker.”Footnote 56 In these ways, Amateau’s Jewishness may well have bolstered his authoritative and spiritual air, much like other Muslim, Christian, and Jewish migrant merchants from the Mediterranean served as “authenticators” of the products they sold.Footnote 57

Location was (also) everything. Caribbean Botanical Garden was far from Amateau’s Bayside home, but its location allowed the business cannily to weather demographic changes underway in East Harlem. The neighborhood, once the land of the Lenape indigenous peoples, was by the turn of the century predominately white (Italian, German, Irish, and East European Jewish), and in the years after the First World War,rapidly became an African-American and Afro-Caribbean mecca. The shop’s address, 80 East 115th Street, was two doors from Alberto Rendón’s enormously popular West Indies Botanical Garden, the first botánica of New York City.Footnote 58 Amateau’s must have hoped for a spill-over of clients, or that the address itself lent his store credibility. Equally as important, Caribbean Botanical Garden was a mere seven blocks from Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Church at 115th St and Pleasant Avenue, then the epicenter of New York City’s largest Italian neighborhood.Footnote 59 The heart of the community was the church, which housed a revered statute of the Virgin Mary that is one of only three in the United States to have been blessed and venerated by the Pope. Since 1884, the church has held an annual feast on 16 July in honor of the Virgin Mary during which the Madonna is paraded through the neighborhood followed by those whom she has healed. When the Italian community of East Harlem was at its height, in the decade that Amateau opened Caribbean Botanical Garden, half a million revelers joined the Festa each year.Footnote 60 This was a community hungry for the goods Amateau sold, and he could communicate with them easily in native Italian.

Black consumers, too, would have been crucial to the business, not only those who lived in or near East Harlem, but those who lived elsewhere in New York City—many botánica patrons prefer the discretion ensured by an establishment at a distance from home. The Harlem Renaissance gave Hoodoo a boost, drawing the interest of pioneering intellectuals like Zora Neale Hurston. Famously, in the late 1920s Hurston conducted anthropological field work throughout the American South among Hoodoo doctors (including the legendary priestess Marie Laveau), undergoing initiations to become a practitioner as well.Footnote 61 Beyond the intellectual milieu, the popularity of Hoodoo remained robust. By at least 1940 Amateau was targeting African American buyers in need of mail order supplies for the practice of Hoodoo, promoting Caribbean Botanical Garden (as Caribbean Products) in Black newspapers in the Northeast and Midwest. One of his first advertisements, published in the Baltimore-based Afro-American, enticed customers with “Spiritualist’s Supplies.” The small advertisement offered loadstones, oils, incense, and candles.Footnote 62 Amateau would maintain this advertising strategy for some years.

By the time of Caribbean Botanical Garden’s opening, Amateau had lived on the island of Rhodes in its Ottoman and Italian incarnation, dwelt and worked in Central and Southern Africa, sojourned with family in Istanbul, and transplanted himself to New York City. One place with which he seemed to have no personal tie was the Caribbean.Footnote 63 It is true, Jews and New Christians of Iberian descent who moved to Brazil, Surinam, Curaçao, Santo Domingo, Jamaica, and Barbados beginning in the fifteenth century experienced extensive interplay with Black Atlantic and Afro-Caribbean spiritual practices, and these forms of cultural fusion persisted into the modern period.Footnote 64 Yet, these communities had little to no overlap with the world of the Amateaus and Ottoman, Judeo-Spanish-speaking Jewry. The name Amateau pinned upon his shop (Caribbean Botanical Garden) and that which he used to advertise it in the African American press (Caribbean Products) asserted an association with the religion, herbal medicine, and traditions of divination of the Black Atlantic. The name emphatically bridged Amateau’s Mediterranean roots and Atlantic world engagements, claiming an affiliation with Black culture while positioning Caribbean Botanical Garden at a distance from predominant American racial hierarchies.Footnote 65 It was surely also designed to appeal to Harlem’s rapidly growing Caribbean community, which the young entrepreneur would have wanted as patrons.

As ever more Puerto Ricans, Haitians, and eventually Cubans moved to East Harlem in the 1930s and after the Second World War, these communities became central to Caribbean Botanical Garden’s patron base.Footnote 66 Within this broad frame, the Sephardic and Puerto Rican communities in East Harlem had particularly intertwined histories. They not only lived alongside one another and spoke the same language (or mutually intelligible forms of the same language), they also worked together, engaged in labor organizing together, patronized one another’s businesses, and sometimes their members fell in love and/or married.Footnote 67 The second wife of Amateau’s brother Morris/Musani Amato was a Puerto Rican professional flamenco dancer named Anna Anduze. After meeting in New York, the pair moved to Puerto Rico to raise a family and their descendants live there still.Footnote 68

Despite the fact of such Sephardic-Puerto Rican intimacies, when it came to the realm of spiritual knowledge, Amateau would have needed a cultural go-between in tune with the needs of his burgeoning Caribbean neighbors. He found assistance in an employee named Juba, about whom his daughter remembers little aside from the fact that he was “Black, and from the [Caribbean] islands.” About Juba we have woefully little to work with aside from his name. This so-called “day name” is commonly used by the Akan Caribbean descendants of enslaved men and women from West Africa (what is currently Ghana), though non-Akan-descended children carry the name as well.Footnote 69 Juba and Amateau were “very close,” and Juba was involved in the daily running of the business.Footnote 70 Intermediaries like Juba were instrumental to the botánica industry as a whole, and were particularly necessary for immigrant healers like Amateau; in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese doctors in the United States similarly sought out business partners with native English and Spanish speakers.Footnote 71 To this day, Jewish-owned spiritual wares businesses rely on a largely non-Jewish, Latinx, Caribbean, and Black employee base. Anthony Lopez, the longest-serving employee of Original Products Botanica (a Jewish-owned botánica in the Bronx and a descendent of Caribbean Botanical Garden) calls himself “an underpaid therapist.” The notion that Lopez serves as a “therapist” to his clients references the medical services botánicas provide their customers, who are for various reasons unable or unwilling to consult a practicing physician. The suggestion that he is “underpaid” points also to the complexity of class and race relations that have conditioned Jewish-owned and Latinx, Caribbean, and Black-staffed botánicas for nearly a century.Footnote 72

Frictions around these issues did not only surface on the botánica floor. According to Amateau’s daughter Micaela Amateau Amato, when her father came home at night, “he smelled very strongly. He didn’t smell like the fathers of other friends. They thought my father was odd and exotic and strange.” Amateau Amato’s sister Judy Hazary also clings to the potent memory of her father’s aroma. “Inside the dimly lit store [of Caribbean Botanical Garden] were the exotic fragrances of incense and soaps which we [daughters] recognized on our father each night he returned from work.” The odors, she has written, “were unique to us. Mysterious and foreign to everyone [else]. We understood without his explanation that we were different from our friends and neighbors, as American as everyone else yet not the same.”Footnote 73 Upon his skin, Amateau bore the imprint of the products he sold to an Italian, Black, and Brown working class clientele, in a neighborhood less white and middle-class than the one in which his daughters were raised. Still and all, Micaela Amateau Amato perceived the Sephardic and Mediterranean legacy in her father’s work. Her own grandmother frequently wore homegrown, medicinal herbs on her forehead, tucked inside a swath of fabric. “We wore hamsas, touched the mezuzah on the door: this was no different. My father was extremely respectful of other religions. I grew up very comfortable with Catholic people, Black people, people who had religions like Santeria.” While her sister cried foul, Amato felt her father’s shop repurposed Jewish spiritual practices. This act of repurposing carried a bit of Rhodes into Harlem and then Queens, utilizing “foreign signs” in a fashion that was entirely in keeping with Caribbean mystical practices.Footnote 74

Hazary’s discomfort with her father’s aroma alerts us to something crucial in Amateau’s and Caribbean Botanical Garden’s history. For all the cultural melding that went on within Amateau’s botánica, the Amateaus drew a boundary between the urban, multi-ethnic, commercialized encounters essential to Caribbean Botanical Garden and the whiter, suburban, domestic environment they claimed as home. Amateau’s business was in Harlem, but the family’s social capital was invested in Bayside, Queens. Their commitment to Sephardic tradition inevitably shifted by and within this environment. Bayside was not home to many Sephardic Jews aside from the Amateaus, and so the next generation was raised in a majority-Ashkenazi community and affiliated with the majority-Ashkenazi Temple Beth Shalom, which might have felt especially comfortable to Amateau’s wife, Ann (née Resnick) Amateau, who was of Ashkenazi background.Footnote 75 Still, the family as a whole were strong in their Sephardic, Italian, and Mediterranean identifications.Footnote 76

Amateau also channeled Jewish tradition within the walls of Caribbean Botanical Garden, though arguably not the biblical or Kabbalistic influences that his clients might have expected. According to one of his daughters, menorahs, stars of David, and Jewish ceremonial objects were among the goods Amateau stocked in the store, notwithstanding the fact that his clientele was overwhelmingly (if not entirely) non-Jewish.Footnote 77 What’s more, his botánica commodified—but also transformed—Eastern Mediterranean Jewish and, even more specifically, Rhodesli Sephardic folkways. Harold’s mother Rachel grew the herbs and plants her son distilled into oils or sold as cuttings or seedlings, much like her grandmother might have done. She also personally distilled the oils he sold and oversaw the making of curative powders. A particularly precious photograph of Rachel Amateau shows her in front of her roses in her Bayside garden holding what appears to be challah in one hand and a bowl of food in the other. Balanced expertly in her mouth is a lit Pall Mall, her cigarette of choice (image 6). Her garden provided the Rhodesli-inspired raw goods that her son could transform into herbal and herb-derived treatments for a diverse, non-Jewish clientele. Rachel Amateau also helped Caribbean Botanical Garden fuse cultures concretely and chemically, through the mixing and sale of herbal and herbal-derived products.

Image 6: Rachel Amateau in Bayside garden, ca. 1940s. Photograph courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

While Amateau’s mother generated the essential botanical ingredients and know-how to craft products for Caribbean Botanical Garden, his daughter Micaela Amateau Amato sewed amulets into which her father placed personalized blessings. Amateau Amato also illustrated the labels Amateau glued on candles and other products.Footnote 78 Rhodes was a source of inspiration for the Amateaus, but together they were embarking on what Raquel Romberg calls “ritual piracy”—the ingenious and fluid melding of competing social, cultural, and aesthetic regimes. This set of regimes included the Rhodesli, Sephardic, Mediterranean, residual Ottoman, early Italian, and Central African, as well as that complex cultural world that took shape in early and mid-century East Harlem.Footnote 79

The spectacle of the invisible

Caribbean Botanical Garden spawned a small empire of Sephardic-run, family-owned botánicas in New York and Atlanta, some of which are today operated by a third generation. As this article draws to a close, I will briefly trace Caribbean Botanical Garden’s legacy forward in time, and outward from Harlem to other boroughs of New York City as well as Atlanta, Georgia, highlighting the enduring inheritance of this business.

Amateau’s brother Morris/Musani was the second in the family to move into spiritual wares. In 1942, he opened Nidia Botanical Gardens at 70 East 114th, a mere block from Caribbean Botanical Garden. Sal Volpe, an Italian Catholic competitor in the botánica business and one-time partner of Morris/Musani Amateau, has recalled that “Spanish” perfumes made with real floral essences (such as “Jabon de Patchuli” and “Locion Sándalo”) were among Nidia’s draw. Morris/Musani Amateau imported rose petals in bulk from overseas suppliers to meet demand for the product, and it was said that “the motion of the ship helped extract the scent.”Footnote 80 The trade route and context were of the new world, but the commodity was of the old: rose oil had long been produced and treasured by Ottoman Jews.Footnote 81 Early on Nidia Botanical Gardens, like Caribbean Botanical Garden, placed advertisements in the African American press, and at times the neighboring shops were promoted in advertisements published side by side (image 7). Yet it was Nidia Botanical Gardens that would prove the enduring business and stake a claim, accurately or not, to be the family’s foundational and most significant venture into the botánica industry.

Image 7: Selection of advertisements, including advertisements for Caribbean Products Co. and Nidia Botanical Gardens,, African American 14 July 1945.

The Amateau family extended its reach in the spiritual wares industry outside of New York City in 1944, when two cousins, Jack and Morris Amato, opened a botánica in Atlanta at 171 Mitchell Street, in the historically Black neighborhood of Southwest Atlanta.Footnote 82 The cousins referred to themselves as the “Brothers Reverend Jack Rondo and Reverend Morris Rondo” in promotional materials, and though they positioned themselves as spiritual authorities of Hoodoo, they were Sephardic Jews from the extended Amato/Amateau clan of Rhodes. (Jack and Morris Amato were both born in Georgia, but their parents, Menashe/Manashe and Luna Amato, were children of Rhodes.Footnote 83) The multi-pronged business they created in 1944 continues to operate under the names Rondo’s Luck Shop, Rondo’s Temple Sales Co., The Lucky Candle, and Rondo Distributing Co. Rondo’s Luck Shop is today managed by a third generation of the family, still actively Jewish, nonetheless represented by the “Reverend Michael Rondo and Reverend Darren Rondo,” also known as Michael and Darren Amato. According to its website, Rondo’s Luck Shop’s “areas of expertise include reuniting loved ones, spell and hex removal and casting, helping out with money and financial situations, employment issues and more.”Footnote 84

Back in East Harlem, as Harold Amateau’s eyesight failed in the 1960s, he closed Caribbean Botanical Garden and joined his brother Morris/Musani Amateau as a partner in Nidia. Fraternal relations were fraught. At some point the brothers came to distrust each other, with each pointing to the other as untrustworthy.Footnote 85 When Amateau entered retirement in roughly 1969, Morris/Musani Amateau was joined in the business by his son Albert, and these two generations of Amateaus relocated the family operation to 73 East 115th Street, renaming it Nidia/M. & A. Amateau Incorporated. This same year M. & A. Amateau had a number of patent requests approved by the government, including a trademark request for the name “Nidia” itself.Footnote 86 Albert’s son Robert joined the company in 1971, and Robert’s brother Steve joined him as an equal partner after the death of their father and grandfather in 1984. So the business endured in third-generation family hands as a storefront, retail, and mail order operation selling an enormous array of goods—“roots and herbs, books, talismans, religious pictures, fortune telling cards, sheepskin parchment, copper bracelets, saltpeter, lodestone and magnetic sand, camphor tablets, powdered sulfur, mercury, turpentine, ammonia, benzine, and coal tar” as well as baths, floor wash, waters, perfumes, soaps, aerosol sprays, salts, rubbing alcohols, incense, oils, and candles”—much of which were manufactured in the back and upstairs of the building.Footnote 87 Alas, M. & A. Amateau Incorporated succumbed to fire (as do so many botánicas, bursting as they often are with burning candles) in about 2000, forcing the family to reinvent yet again.

Still the legacy persisted, with the arc of time bending back on itself. The fire reunited branches of the family that had once split apart. It happened like this. Amateau’s brother-in-law Milton Benezra, who cut his teeth as a spiritual merchant working for M. & A. Amateau Incorporated, had broken away in 1959 to create his own store, Magi Botanical Garden on Bathgate Avenue in the Bronx. There he began to formulate powders, baths, and oils. When the Bathgate store, too, burned in 1969, Benezra and his friend Jack Mizrahi partnered to open a business that would become Original Products Botanica, today located at 2468 Webster Avenue, just down the road from Fordham University.Footnote 88 According to Mizrahi’s son Jason, Benezra was a bit more visible in the front of the store where he oversaw its commercial workings, while his father Jack excelled in its private corners and was embraced by patrons as a healer.Footnote 89 After the founding generation of Original Products Botanica retired, Jason Mizrahi partnered with Albert Amateau’s sons Robert and Steve, erstwhile inheritors of Nidia/M & A Amateau Incorporated. Robert passed away prematurely, but Jason Mizrahi and Steve Amateau continue to run Original Products Botanica to this day, and have kindly opened their doors, memories, and paperwork to me in the course of my research (images 8a and 8b).

Image 8a: Original Products Botanica, 2486-88 Webster Avenue, New York City. Author’s photo.

Image 8b: Original Products Botanica, 2486-88 Webster Avenue, New York City. Author’s photo.

Original Products Botanica describes itself as the largest botánica on the east coast, and because of its scale and longevity, the shop has been the subject of various popular articles, including one by the New York Times that refers to the business as “a veritable Home Depot of spirituality.”Footnote 90 Indeed, the operation is of daunting size, and a far cry from the modest footprint of Caribbean Botanical Garden. Original Products Botanica boasts a capacious wholesale division on the ground floor, an upper floor devoted to spiritual consulting and candle burning, and an extensive basement dedicated to manufacturing, storing, and packing the shop’s expansive mail order stock, which is shipped all over the world. A parallel, family-run enterprise (Original Publications) is devoted to publishing original and reissued books on the Yoruba, Santería, numerology, Wicca, astrology, the kabbalah, dreams and numerology, Hoodoo, and Spiritism. These books, too, may be bought on the ground floor of Original Products Botanica.

Scholarly and journalistic coverage of these various, intersecting forays into the spiritual goods industry tells the history of this ambitious Sephardic family and their business ventures variously. Interviews with family members (by myself and, earlier, by Carolyn Long) seem only to confound the effort to pin down a precise chronology or familial or commercial family tree. The jagged picture may well suit the nature of the industry. Record-keeping has been kept impressionistically or chaotically by the family and businesses involved, much has been lost to fire, and competitiveness undergirds the business, resulting in the cagey guarding of proprietary secrets and commercial genealogies.

Putting aside the debate over which family botánica was the first, biggest, or most successful, one thing is clear: Sephardic Jews, and Rhodesli émigrés in particular, exerted an exceptional influence over the botánica industry in New York and across the familial, commercial diaspora that extended from it. One could do worse than track this influence in a 2006 trade book by Wiccan expert Lady Maeve Rhea (writing with Eve Lefay) called The Enchanted Formulary: Blending Magickal Oils for Love, Prosperity, and Healing. This foundational guide to the practice of Wicca is dedicated to Jack Mizrahi, Jason Mizrahi, Milton Benezra, and no less than four Amateaus (Morris, Albert, Steve, and Robert). The list of surnames reads like a Who’s Who of Jewish Rhodes, yet there is no acknowledgement in the book, or for that matter anywhere else, that botánica history is so thoroughly crosscut with Sephardic culture.Footnote 91

If the industry’s own literature erases its Sephardic history, for the families involved, botánica history is immensely present. This is not just true for the third and fourth generations who continue to operate family businesses in New York and Atlanta. Though Aron Amateau/Harold Amato’s descendants have no foot in the spiritual goods trade, the fact of the family botánica casts ripples across the generations. Amateau’s daughter Micaela Amateau Amato, who once hand-drew labels and prayers for her father’s modest shop, is now an artist and Emerita Professor of Art at Pennsylvania State University, producing art that self-consciously reflects the influence of her father’s commitment to alternative healing and her Sephardic past, including multi-media work that features repurposed photographs of Caribbean Botanical Garden (image 9).Footnote 92 Amateau Amato has also created neon-lighted Ladino and English-language texts that are (in the artist’s words) “private lamentations or cries for social justice”—one of these, “I am the Spectacle of the Invisible,” a phrase drawn from her daughter Cara Judea Alhadeff’s writing, provides this sub-section its evocative title.Footnote 93

Image 9: Micaela Amateau Amato, “115th Street.” Multi-media art courtesy of Micaela Amato Amateau.

This article is not intended, as I hinted at its outset, to be a story of the Jewish strange. For those in the extended Amateau/Amato family, for those who patronized (or still patronize) Caribbean Botanical Garden, Nidia Botanical Garden, M. & A. Amateau Inc, Original Products Botanica, or Rondo’s Luck Shop, the family’s past merges seamlessly with a spiritual and commercial present—so much so that some of the founding generation of Sephardic botánica owners positioned themselves, and by some accounts were embraced by clients, as healers, seers, mystics, conjurors, or Hoodoo Reverends in their own right.

This exploration has infused the botánica with a Jewish and Eastern Mediterranean dimension that deepens what we know of the complexity of these commercial, spiritual, racialized, and cultural spaces. Jewish family trees loom large in this account of the early spiritual wares trade in the United States, with roots deeply impacted in Europe, the Ottoman Empire, Italy, Mediterranean, and Central Africa, as in urban American neighborhoods such as East Harlem, Southwest Atlanta, and Chicago’s South Side. So too this study—much like Micaela Amateau Amato’s neon art and Richard Kostelanetz’s ruminations—has cast light on invisible chapters of Sephardic history. It illuminates a meandering and intriguingly non-linear tale of racial encounters and reinventions, through which a Rhodesli, Ottoman, Italian, Jewish émigré became a white merchant in southern and Central Africa before reinventing himself as a purveyor of Italo-Afro-Latinx-Caribbean spiritual goods and something of a mystic, too, in East Harlem.Footnote 94 Building upon literature on Jews’ gravitation towards certain ethnic, mercantile niches, I have pointed to a hidden domain of such activity—the spiritual wares trade—and leveraged it to explore Sephardic émigré merchants’ commercial relationships with the Black, Caribbean, Latinx, and Italian consumers who patronized their shops.

Some Jewish-owned botánicas operating today bear little resemblance to Caribbean Botanical Garden: they have become empires, “Home Depots,” carrying everything from statues of Jesús Malverde, patron saint of drug dealers, to vape pens. Yet even as product lines expand, certain trusted, essential items that Amato might have sold in the 1930s remain in stock—the statuary, the Tarot cards, the essential oils and herbs, the candles. This is true even of highly “sanitized” places like Marty Mayer’s expansive Indio Products, “The World’s Most Complete Manufacturer and Distributor of Spiritual, Religious, and New Age Items,” which Marty kindly toured me through in its most recent, East Los Angeles location adjacent the L. A. River, in an industrial district near where the 710 crosses Highway 5.

Telling a story of “botánicas Sephardicas” allows us to grapple with the nuanced Eastern Mediterranean dimension of botánica history and to render visible Jews who were always perceptible in their own commercial, familial, spiritual, and racial orbits, but who have been rendered invisible to a wider public and scholarly eye. To do so is to shed light on a variety of entanglements (of race, class, religion, and neighborhoods) that take shape at the meeting of multiple diasporas and trans-oceanic flows. Aron Amato/Harold Amateau would surely have packed the box more neatly. Hopefully with his intuitive vision, he would also see some truth in this account.