The instability or flightiness of elephants is the characteristic that made them so unreliable and dangerous to their own troops during their early use in warfare. Historians cite frequently that the elephants, by stampeding, did more damage to the men of their own army than they did to the enemy.

———Francis G. Benedict, The Physiology of the Elephant. Footnote 1Many scholars hold a skeptical view of the war elephant of ancient India. I am not one of them.Footnote 2 I propose, and will give evidence to show, that the skepticism of present-day scholars derives from ancient Rome, at the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Empire, when the Romans, having defeated the elephant-using powers of the Hellenistic period, ceased using war elephants and in doing so eliminated their use in the Hellenistic world where it had flourished. Roman war elephant skepticism was not invented by Quintus Curtius Rufus but he embraced it and strengthened it rhetorically in speeches he devised and put into the mouth of Alexander of Macedon, in his history of Alexander, written centuries after Alexander’s death. In this way, Roman skepticism about the value of the Indian war elephant was attributed to Alexander, long previous to the formation of that Roman skepticism: it is an anachronism. Pier Damiano Armandi in the nineteenth century renewed and modernized Curtius’ skepticism, rendering it a fact of military science; and Francis G. Benedict in the twentieth century, referencing Curtius and Armandi, furthered its reach by making it into a fact of natural science, lodged in elephant physiology. Scholars of all kinds were persuaded, and skepticism of the war elephant became, and remains, a commonplace, needing no demonstration. (A shining exception is H. H. Scullard; another is A. B. Bosworth, who followed the war elephant closely, as do the many he taught or influenced.) To reopen the question we need to trace the itinerary along which the unreliability of the elephant was articulated and turned into a trope. The culmination of the process is the epigram with which this article begins.

Curtius is not supported on the matter by the other earliest surviving histories of Alexander (Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, Justin), and the judicious Scullard calls Curtius’ view nonsense. M. B. Charles, in an important study of Alexander’s battle against Poros in the upper Indus Valley of India, citing Scullard, gives reasons to consider Curtius’ rendering of Alexander’s supposed contempt of war elephants as an anachronism, reflecting later Roman views.Footnote 3 Expanding upon Scullard and Charles, and as an historian of ancient India, I offer here a study of the reception and influence of Curtius’ skeptical treatment of the Indian war elephant, not as a contribution to the history of Alexander himself (in which it is of small importance) but for its baleful effect upon the historical study of India, specifically the formation of the Mauryan Empire by Chandragupta, and its relations with states formed by the Diodochoi or Successors of Alexander after his sudden death, in which war elephants and the knowledge of how to manage and deploy them are central. I believe it is important to follow the elephant because it held these two worlds together in a new international dispensation. It is a dispensation, as Kosmin writes, of bounded, equivalent sovereign states that understood themselves to be peers and rivals, replacing the world empire the Persians had created, whose sovereignty was deemed singular and without limit.Footnote 4 I want especially to follow elephants of flesh and blood, and the practical knowledge of them, flowing from India to Alexander’s successors. In a very real sense Alexander’s death provoked the new formation, by the division of his elephants, and by the division of his territory and sovereignty. It was a new international order for which Alexander’s encounter with the Indian war elephant was the essential precondition.

Inevitably the argument developed here is a beginning, one that invites scholarly exchange among regional specialists.

The Roman Meme: Elephants Are More Dangerous to Their Own Side

Roman elephant-skepticism did not come about all at once. Romans first faced elephants in war at the Battle of Heraclea (280 BCE) to which Pyrrhus, king of Epirus in Greece, brought twenty elephants, defeating Rome and its allies. The Romans met elephants again in wars against Carthage, Macedonia, and the Macedonian Seleucids of Syria and the Ptolemies of Egypt, among others, in which Romans were obliged to find ways of defending against elephants. Romans eventually took up the use of war elephants on offense. But they came to believe that the elephant posed a greater risk to its own side and attributed that to a tendency to panic in battle when wounded, and for the panic of one to spread to the others. This became a settled belief of Romans, a meme, we could say. Armandi finds it expressed by Pliny the Elder, Livy, and Appian, as well as Curtius, among ancient texts that have survived.Footnote 5

Romans eventually ceased using war elephants themselves, when they put an end to the elephant-using Hellenistic states, following the Battle of Thapsus (46 BCE) in which Julius Caesar defeated his opponents in the Roman nobility, and the forces of their Numidian ally, Juba I, which included a sizeable number of elephants. The Republic came to an end in 27 BCE, with the assumption of extraordinary powers by Augustus. The Romans abandoned the war elephant for all time, on grounds of their posing a greater danger to their own side.Footnote 6 At Rome elephants continued to be imported from North Africa, now a part of the Roman Empire, but their use was confined to the spectacles of the circus and the triumph. Romans did not resume use of war elephants even when, centuries hence, they met the Sasanian Persians and the elephants they had imported from India, on their eastern frontier.

The hugely consequential Roman renunciation of the war elephant, then, began only in the first century BCE, at the end of the Republic and as the Roman Empire was coming into existence, long after the death of Alexander (323 BCE) and as a result of wars against Hellenistic and North African powers, who had been enthusiastic believers in the efficacy of war elephants.

To follow this evolution properly it is necessary to begin before the formation of the Roman meme, before, even, Romans encountered elephants in the army of Pyrrhus; one must start with the expedition of Alexander across the Persian Empire and into India, where he encountered elephants, and acquired many from his Indian allies, or as spoils from states that resisted him. He brought those elephants all the way back to Babylon.

Historians of India (among them myself) have reason to be interested in the histories of Alexander. The earliest surviving inscriptions in the Brahmi script belong to the third monarch of the Mauryan dynasty, Ashoka, in the third century BCE, while we have no contemporary inscriptions for his grandfather Chandragupta, who, following Alexander’s departure and death, established the Mauryan Empire that covered the greater part of India and reached into Afghanistan. It seems that the use of the new script begins with Ashoka, and if that is so, then it is to the Alexander historians and the fragments of Megasthenes that we must look for evidence on the formation of the Mauryan Empire.

It can be a shock to realize that the five surviving histories of Alexander, one of the most celebrated figures of ancient history, were all of them written three to five centuries after his death—that is, by writers whose lives followed Rome’s great renunciation of the Indian war elephant—and that all of their histories of Alexander are based upon earlier works that are now either entirely lost or survive only as fragments. This is material to the interpretation of the period in between, when the successors of Alexander fostered and spread the use of the war elephant of India by their rivalry, making the India connection a founding dimension of the Hellenistic period, and a continuing feature as it spread to indigenous powers of North Africa. Equally disturbing for historians of India is that the memoir of India by Megasthenes, ambassador to the Mauryan king Chandragupta shortly after Alexander’s withdrawal, also survives only marginally in the form of fragments. Megasthenes’ account goes straight to the heart of the India connection by his contemporary account of the capture and training of war elephants.Footnote 7

But again, for contemporary sources all we have is fragments. The word “fragment” can convey the idea of a piece of a written book, but in this context a fragment is rarely an exact copy; more often it is a paraphrase found in the work of a writer belonging to a later time and using the idiom then current. Anachronism would tend to increase with time. In respect of what we have concerning Alexander and Megasthenes, those who register these fragments are writers in Greek and Latin who come from after the era of the great Roman renunciation of the war elephant. Their manner of purveying fragments of earlier writers has to have been influenced, to some extent, by the massive fact that the Romans had by then put an end to this fighting arm, and never restored it.

The underlying historical phenomenon that makes the period between the life of Alexander and the time of the great Roman repudiation of the war elephant so difficult to assess, then, is the largely unconscious tendency to alter earlier testimony in the retelling. Consider, as an example, the siege of Megalopolis described in Diodorus.Footnote 8 It was attacked by Polyperchon, one of Alexander’s former officers, who had many elephants with him; but he was foiled by Damis, another of Alexander’s former officers, who was leading the defenders and had experience of elephants in Asia. He devised upright spikes (hela) attached to wooden frames (thura) buried in the path of advance for the enemy elephants. Some of the drivers (called indoi, or “Indians,” in its specialized, perhaps later and Ptolemaic, meaning) were killed. In the end, some of the elephants were immobilized, while “others brought death to many of their own side” (ta de pollois ton idion thanaton epenegken). We must consider the possibility that the phrase “own side” may be coloration from the Roman meme, imparted anachronistically by Diodorus to his retelling of a source of the Hellenistic period—who, if that were so, would in all likelihood be Hieronymus of Cardia.

However that may be, anachronism seeping into the retelling of a fragment is clearly revealed by another fragment on the siege of Megalopolis, later still than Diodorus, by comparing how it departs from what Diodorus describes. Called Fragmentum Sabbaiticum, it was written on papyrus by an unknown author and found in a monastery of the Sinai. It adds at least one anachronism, and probably two, to the narrative as we have it from Diodorus. It speaks of wooden towers (purgoi xulinoi) on the backs of the elephants, but such towers, according to Goukowsky’s classic article about King Porus and his elephants, are a Greek invention of a later time. It also asserts the use, not of the spikes in wooden frames that Diodorus describes, but caltrops (triboloi).Footnote 9 The name indicates the three metal spikes upon which the “jacks” rest, but the three support a fourth, upright spike, which does the ugly work. This is entirely different from what Diodorus gives us, and what we find repeatedly and consistently in the other contemporary battles of the successors of Alexander in Diodorus, as Wheatley and Dunn have shown.Footnote 10

In the matter of fragments, historical evaluation has two sides: identifying the author of the text of which it is a fragment, and determining the changes that have been introduced in its retelling by the text of a later time in which it is embedded. For as Brunt has said, “‘Fragments’ and even epitomes reflect the interests of the authors who cite or summarize lost works as much as or more than the characteristics of the works concerned.”Footnote 11 While study of fragments has undoubtedly brought about a great increase of knowledge, very often evaluation focuses on the first prong alone, or the analysis cannot be carried to completion on both prongs of the evaluation on available evidence. This leaves a quantum of uncertainty that blurs the sharp difference we expect to find, in the case at hand, between the Roman meme and the elephant-enthusiasm of the Hellenistic states.

Curtius’ claim that Alexander was tepid about the Indian war elephant is controverted by the latter’s actions and does not accord with the enthusiasm for war elephants of his successors, especially such officers as Seleucus and Ptolemy, dynasts of the large Hellenistic states of Syria and Egypt. The history of the Hellenistic period is distorted by this misplaced conviction of modern scholars, traceable to the Romans, and especially to Curtius. There is also a distortion of Indian history regarding the foundational moment of the Mauryan Dynasty, in the person of Chandragupta Maurya, and its huge empire that embraced most of the Indian subcontinent and stretched westward to Afghanistan. Although Chandragupta is well-remembered in Indian traditions, for the traces of contemporary accounts of India at this formational time we must look to the Greek and Latin records of Alexander, and of the embassy to Chandragupta of Megasthenes in the time of the successors. The two centuries of consequential and continuing interactions between the two histories, Mauryan and Hellenistic, is dimmed, dulled, and downplayed by continuing skepticism about the Indian war elephant. To find a better course, one must start in the time of Alexander, before the Roman meme was formed.

Alexander and Elephants

Alexander of Macedon overthrew the Persian Empire of Darius III, of the Achaemenid dynasty. In preparation for his expedition he would have sought information about the Persian military. The sources available to him, and to his father Philip who had projected the conquest of Persia but did not live to carry it out, would have been vastly superior to those that are available to us, and Macedonia had connections with Persia and felt its influence so that it would have been informed about its military.Footnote 12 Alexander’s first encounter with live elephants at Gaugamela is often rendered as if it were a surprise, but it cannot have been. Engels, in an article on the intelligence system of Alexander, has a good discussion of the strategic information about the Persian Empire that would have been available to Philip and Alexander long before they planned an expedition against it: literary works by Herodotus, Ctesias, and Xenophon, and information from merchants, travelers, artisans, and diplomats, and also high-ranking exiles from the Persian Empire to Philip’s court.Footnote 13

Ctesias is one source on Persia of which we have knowledge through the fragments in surviving texts. Alexander and Philip would have known about the Indian war elephant through the writings of Ctesias, who had been physician to the Persian king and had written a Persica and an Indica. Ctesias’ conception of India was that it was wealthy because of a large population and favorable geography; its wealth attracted invaders, but because of war elephants, which only India possessed, it had never been conquered by outsiders—at least before the Achaemenids, who had Indian satrapies on the Persian side of the Indus River. Alexander would have been aware that the Achaemenids had some elephants from India: Ctesias had seen one topple a palm tree at the command of its driver, in Babylon.Footnote 14 Alexander knew about Indian elephants long before he saw them with his own eyes.

According to Arrian, whose information came from Aristobulus, Alexander first confronted Indian elephants at Gaugamela, in 331 BCE, near Arabela (modern Erbil in what is now northern Iraq). However, as Briant says, neither Curtius nor Diodorus nor Plutarch breathe a word about their presence on that occasion.Footnote 15 Thus, in the surviving histories other than Arrian, the first encounter would have been at the Battle of the Jhelum (Hydaspes) in India, against King Porus.

Darius had an Indian contingent with fifteen elephants at Gaugamela. They were to be stationed in the center, spaced out in a line in front of the king together with as many as fifty chariots with long knives, like scythes, on the hubs of the wheels. This is according to the written battle order, which the Macedonians recovered afterwards.Footnote 16 This disposition conforms to ways in which we know that war elephants were stationed in battle arrays (Sanskrit vyūha) in India. But the elephants may not have arrived in time for the battle, since they are not mentioned in surviving accounts of it and were captured after in the vicinity of the camp. These cannot have been baggage elephants, in my opinion, given the immense cost of elephants this far away from India.

Later, at Susa, the satrap Abulites gave Alexander twelve more elephants, which Darius had acquired from India, according to Curtius, who alone records this deed.Footnote 17 This corps of elephants would have been of great value to Alexander in preparing himself for battle within India. He eagerly acquired more of them, as we shall soon see, from the Assacenians, who lived on the hither side of the Indus River, which is to say, again within the territory of the Persian Empire. Briant rightly notes in this connection Arrian’s remark about Indian kings bringing elephants to Alexander as gifts of the kind most prized by them.Footnote 18

Thus the Achaemenids undertook the expensive and complex task of acquiring elephants in India and marching them long distances, probably along the network of royal routes, which had storehouses of provisions for those having authority to draw upon them along the way. They must also have learned practices to manage and care for them, which could only have come from Indians. In these ways the Achaemenids anticipated Alexander and his successors in the Hellenistic period, if only in small, providing an example that was emulated at scale by those successors in their wars among themselves following his death. The Achaemenids showed that the Indian war elephant could be adopted beyond India, a lesson of which the evidence is contained in Aristotle, when both Persian and Macedonian measures appear in his discussion of the daily ration of captive elephants.Footnote 19 Alexander set about immediately acquiring Indian war elephants, while in Persia.

Alexander spent three years in India (327–324 BCE). Even before crossing the Indus River he encountered Indian peoples, among them the Assacenians (Assakenoi), whose name has as its first element the word for horse in an Indian rather than an Iranian form (Sanskrit aśva-, Prakrit assa-, Median and Persian aspa-). Some fled on Alexander’s approach, leaving their elephants to graze on the banks of the Indus. He sent officers ahead to spy out the territory and interrogate anyone they might find, for “he was especially anxious to find out about the elephants,” in Arrian’s account. “Now many of the Indians are elephant hunters, and men of this class found favor with him and were kept in his retinue, and on this occasion he went with them in pursuit of the elephants.” Two of the elephants were killed when they threw themselves over a cliff; the others were caught, mounted by drivers, and added to the army.Footnote 20

The Assacenians were said to have had thirty elephants, minus the two that died, so that Alexander more than doubled the number of his elephants, to fifty-five, and as we see, he also took on Indian experts to care for them. He acquired more elephants in India. The total at the time he left India was about two hundred,Footnote 21 and we must assume that Indian staff to care for them were added to the army in proportion, starting with drivers and grasscutters.

Alexander had his elephants with him when his crossing of the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) was prevented by the Indian king Porus (Puru or Paurava) on the other side, with his elephants. After making several seeming attempts to cross in daytime, Alexander made a night crossing far upstream with a force of cavalry and infantry, leaving his elephants in camp. A great storm arose—it was the beginning of the rainy season, at mid-summer—and it covered the sight and sound of the crossing so that the surprise was complete; made more complete perhaps because the rainy season generally brought a full halt to long-distance trade for three months, and armies would not usually march forth during the rains either, which would have made the crossing at such a time unexpected.Footnote 22 Porus sent chariots commanded by his son, possibly because it was the fastest thing available in this emergency, but they got stuck in the mud. Porus would have known this might happen; it shows his desperation to meet the crisis. The chariots took the worst of it, and his son was killed.

The elephants, much the best for the wet conditions, arrived and formed a spaced-out line with the other forces, as in the battle plan the Persians had for Gaugamela. Alexander’s cavalry on the left circled around behind the army of Porus and engaged with his cavalry, pushing it back into the elephants, creating crowding which threw their formation into confusion, without the Macedonian cavalry having to confront the elephants directly. To the fore, the Macedonian infantry also did their damage at a distance with their spears, at least at first. This is the gist of the action, as we find it in Arrian. Alexander’s army got the victory, but the fighting was hard and long, and it left his men with reason to wish not to face the Indian elephant again.

Advancing further east along the main route across India—the Uttarapatha (Northern Route), or what the British came to call the Grand Trunk Road—the Macedonian army reached the Beas River (Hyphasis) on the eastern edge of the Indus Valley, where it met the Valley of the Ganga. Ahead lay the consolidated power of the Nanda dynasty, kings of Magadha whose kingdom had been expanded by ambitious rulers till it engrossed most of the region, making it the largest army in India. The intelligence was that the fourfold army of the Nanda had two hundred thousand foot, twenty thousand horse, two thousand chariots, and three or four thousand elephants.Footnote 23 This was greater, by an order of magnitude, than the army of Porus, said to have totaled thirty thousand foot, four thousand horse, three hundred chariots, and two hundred elephants.Footnote 24

These numbers, however approximate, are very telling, for they confirm the general truth that the richness of the Ganga Valley could sustain an army of immense size. More especially, numbers and quality of elephants increased across northern India as one moved along the Northern Route from Gandhara, in the grassy horse country of the northwest, to Magadha and Anga in the monsoon forests of the east, with its abundant wild elephants. The army of Alexander was entirely correct in its expectation that the Nanda, who had subdued most of the Valley of the Ganga with a large army, including a vastly superior elephant force, would be a more formidable foe than Porus had been.

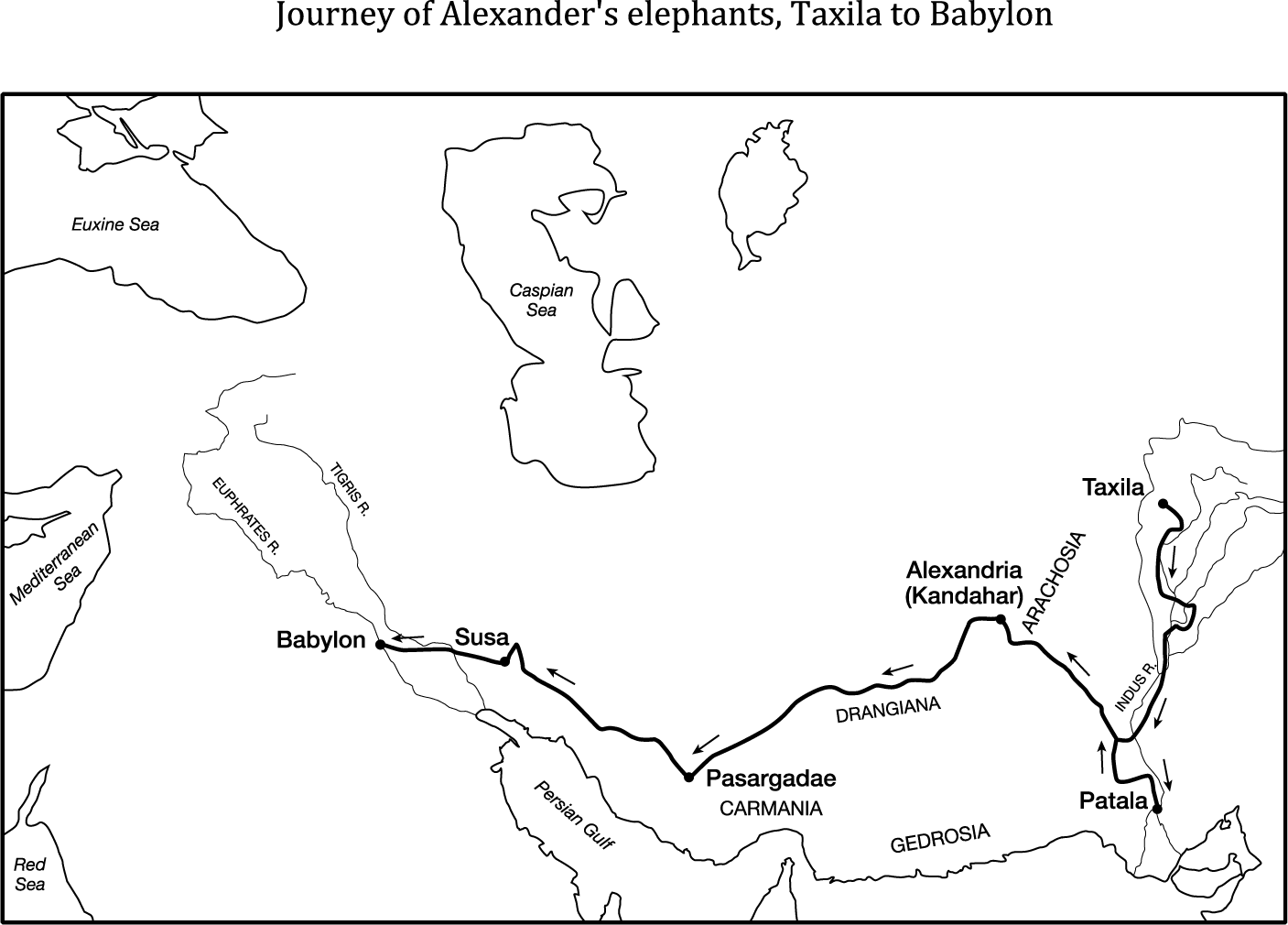

The army refused to advance. Alexander sulked in his tent for a time, before he acquiesced, and set in motion the return to Babylon. The return journey was not a retracing of steps, but rather a continuation of the conquest of India. They moved down the Indus River to its mouths, after constructing a fleet to transport some of the army, while other branches under Craterus and Hephaistion marched down either side of the river. Along the way it received the submission of some states, and the resistance of others, which were put to a fight. It is notable that Alexander received some further elephants as gifts and as spoils, but his army did not face elephants again in battle. This was likely due, it seems to me, to the speed with which the attack force was able to move, a specialty of the Macedonian army from the time of Alexander’s father, Philip. Possibly elephants were left behind because they would have compromised that speed.Footnote 25

Once at the mouths of the Indus, Alexander formed a smaller force to explore the coast, which was little-known. The flotilla he had formed to descend the Indus was now to proceed by sea in parallel with the land force along the coastline. However, men who had aged out of the service were, along with elephants, put under a separate command, led by Craterus. They planned to return inland along the Achaemenid system of routes, through Arachosia, along which, perhaps, there were still-functioning Achaemenid state store-houses for fodder. They were the fortunate ones. The exploratory expedition, under Alexander, suffered terrible deprivations in the arid, unpopulated regions along the Makran coast, and at one point they had to eat their baggage animals; it is said that only a quarter of that army returned. Because the monsoon winds blew directly against it, the navy was stuck in port and could not relieve the army. It was a disaster, from which the elephants were spared by the decision to divide the forces so that their numbers were not too large as they crossed a poor and underpopulated region.Footnote 26

After the reunion of the two land-forces in Carmania, the elephants were assigned to Hephaistion, who took them the rest of the way. Alexander returned to Babylon, as did his two hundred Indian elephants. He died suddenly, in midsummer of 323, at the age of thirty-two.

The aftereffects of Alexander, upon his army and the territories they held, were enormous. The effect most pertinent here was that the large number of the would-be successors of Alexander made for a complicated rivalry among them, increasing manyfold the demand for the Indian war elephants. The original herd of two hundred was partitioned among the successors, but more could be gotten from India. Eumenes, in about 318 BCE, brought back a large contingent from India, such that he came to be called elephantarchos, ruler of elephants, as if he ruled more elephants than humans. Somewhat later it was Seleucus who had the greatest success in doing so, since he was positioned to command Syria and the eastern portions of Alexander’s empire, abutting India. Ptolemy, another officer of Alexander, ruled Egypt, and was cut off from the landward routes to India by Seleucus, who was at first an ally but became a rival. The Ptolemies created a great machinery to capture and train African elephants for war, using Indian techniques and Indian personnel, which have left distinct traces. We can grasp the scale and difficulty of the undertaking from excellent studies by Burstein of Ptolemaic elephant hunts in Nubia and Sidebotham on the excavation of the Red Sea port of Berenike.Footnote 27 African states—Carthage, Numidia, Mauretania—followed the example of the Ptolemies and took up the capture, training, and use of the war elephant.

As Reuss observed long ago, the word Indoi (Indians) acquired the specialized meaning of elephant drivers in the Hellenistic period. This term is not attested in Alexander’s lifetime, and in Diodorus, it appears not in the seventeenth Book on Alexander but only in the eighteenth, on the successors. Goossens has shown that the dictionary of Hesychius at Egyptian Alexandria has several reflexes in Greek corresponding to Sanskrit words of military import: aṅkuśa (the distinctive two-pointed Indian elephant hook), kandara (goad), niveśa (army camp), and mahāmātra (“a general among the Indoi”). This last is especially intriguing, for in five words Hesychius brings together two words for elephant driver in different languages: Mamatrai: strategos para tois Indois. For in Sanskrit mahāmātra is a word for elephant driver, whence mahout in English, via mahāvat (Hindi). (There are however other words in Sanskrit, notably hastipaka, “elephant keeper.”) We could take Indoi in its special meaning here; Hesychius, I suggest, is saying that mahāmātra is a special kind of elephant driver, or a rank among elephant drivers, namely their general or military leader, or their superior: the officer commanding the elephant drivers in battle.Footnote 28

Much of the scholarship on the Hellenistic period minimizes elephants, which are so central to the rivalries among the successors, and I incline to blame the continuing influence of Curtius for scholarly soft-pedalling of this dramatic development. Some show a feeling that elephants are a burden rather than an asset. Thus Bigwood says that the elephants Alexander gained at Gaugamela were presumably taken to Babylon and probably left there. But this hardly accords with Arrian’s testimony, which shows Alexander eager to acquire elephants before crossing the Indus, or the abundant testimony that he took elephants on the army, all through India and back to Babylon. Similarly, Kosmin suggests the reason that Chandragupta readily gave Seleucus five hundred of his elephants was to spare himself the cost and trouble of returning them to the capital (at modern Patna, in Bihar).Footnote 29

Turning to India, Alexander had an effect that was tremendously disruptive, but brief, and scarcely any trace of it remains in surviving Indian sources. But the unintended aftereffects were huge and lasting. For with his departure his Indian possessions fell into chaos, and were overtaken by the growing power, expanding westward from the Valley of the Ganga, of Chandragupta Maurya. He created the first all-India empire starting in 321 BCE. He had overtaken the Nanda Empire of the Ganga Valley and then expanded his growing power into the power vacuum of the Indus Valley.Footnote 30 He clashed with Seleucus, former officer of Alexander and aspiring heir to the latter’s eastern territories, and the two formed a peace, which further extended Chandragupta’s empire, across Afghanistan. I believe the Mauryas continued to supply elephants of war to the Seleucids.

Although we have little contemporary evidence from India for the reign of Chandragupta, the measure of his impact may be judged from the formation, six centuries after, of the empire of the Guptas (320–550 CE), for it presented itself to the Indian world as Magadha re-ascending, and the Mauryan Empire come back to life. It is no accident that its founder took the name Chandragupta, as did his grandson. Most of the surviving Indian sources of the life of Chandragupta Maurya come from the time of the Gupta Age (320–550 CE) or later. The life is an historical enigma, but the person has never been forgotten.

Curtius on Alexander

Grant Parker’s intriguing and fertile notion of “the making of Roman India” is a useful frame in which to examine Curtius’ history of Alexander on the matter of the Indian war elephant.Footnote 31

There is, of course, no such thing as Roman India, and for that matter, the Romans did not conquer Persia either, as Alexander had. The Romans never gained imperial rule of India as a province. Alexander literally had done so, however partially and briefly, as had the Persian Empire before him, while Roman India is a cluster of attitudes and evaluations and themes about India that, however vivid, never come to earth.

Of the Alexander-historians, Curtius has a large role in Parker’s book, being of special interest “because of the highly wrought rhetorical style of his work,” reflecting the influence of the schools of rhetoric at that time.Footnote 32 Curtius is opinionated and expresses himself loudly, on India, in ways far from flattering. Like Arrian and Diodorus, Curtius also knew the book on India written by Megasthenes, the ambassador sent by Seleucus to Chandragupta, the Indian king who overtook the holdings of Alexander in the Indus Valley.Footnote 33 He used Megasthenes when writing an overview of India as background to the narrative of Alexander’s conquests. From Megasthenes, Curtius took matter from which to formulate a reproving passage on the excessive luxury of the king of India,Footnote 34 who was in fact Chandragupta Maurya. Accordingly, Curtius will be the main focus of the analysis that follows here.

Curtius’ identity and date are unknown; we would perhaps know more were it not that the preface to his book is lost. Moreover, no surviving work of antiquity cites his history of Alexander by name. To be sure, we have only a very small fraction of all the writings of antiquity, but even so it is a cause for scholarly anxiety, not entirely allayed by the fact that the work itself has survived to the present.

A. B. Bosworth has given an elegant proof that Tacitus borrowed many passages from Curtius without naming him.Footnote 35 The analysis is convincing and has the bonus of showing that Curtius’ history of Alexander was so widely read that Tacitus did not have to name it for readers to grasp the allusion. The recent collections of Wulfram and of Mahé-Simon and Trinquier further map the European use of Curtius in the Middle Ages and through the nineteenth century, when he came to be considered a master of Latin prose.Footnote 36 From internal evidence his date belongs to the first century BCE, according to Baynham.Footnote 37

As I have said, Curtius did not originate, but he fully embraced, the Roman belief that elephants were a greater danger to their own side, and he gave it great rhetorical power by putting it into the direct speech of Alexander. It occurs in the speech to his men at the Beas (Hyphasis), where they are unwilling to advance further into the Valley of the Ganga and face the massive army of the Nanda, with its many elephants. Curtius coordinates this aspect of the speech with words he attributed to Alexander at the prior battle with Porus, across the Jhelum (Hydaspes).

At the Beas, Alexander is made to say to his men,Footnote 38 “For my part, I so despised [contempsi] those animals that after I had them, I did not make use of them against the enemy, knowing well enough that they inflicted more damage on their own side than on the enemy.” This knowledge of the elephant’s supposed weakness, if from direct experience, could have been gotten at the battle with Porus at the Jhelum. And yet Alexander had elephants with him there, on the hither side of the river, but left them under the command of Craterus, while making a night crossing upriver with infantry and cavalry to surprise the enemy. The project of a secret crossing is sufficient to account for having left the bulky, noisy elephants in camp. His alleged contempt for elephants is not needed to account for his not taking them with him on this occasion, and indeed, taking them would have notified the enemy, even under cover of darkness, that a river-crossing was afoot.

The speech at the Beas, then, has been coordinated with the recent prior action at the Jhelum, in which Curtius appears to have constructed direct speech for Alexander to support the former. I draw attention to two passages.

At first sight of the full body of the army and its elephants, which at a distance looked like towers, and of Porus, a man of exceptional height seated upon the tallest of the elephants, Alexander exclaims stoutly,Footnote 39 “At last I behold a danger worthy of my spirit; I am dealing at the same time with beasts and with remarkable men.” Alexander issues orders for the cavalry, which includes Ptolemy, and then addresses his officers assigned to the infantry:Footnote 40

You, Antigenes, and you, Leonnatus, and Tauron, will at the same time advance against the center and attack their front. Our spears, which are very long and strong, will never serve us better than against these beasts and their drivers; bring down those who are mounted on them and stab the brutes. It is a doubtful kind of strength, and rages more violently against its own men; for it is driven against the enemy by command, against its own men by fear.

Here the “greater danger to its own side” meme is invoked, but in this case its instantiation is yet to come, leaving unexplained from what earlier experience Alexander had acquired this conviction. Nevertheless, in the sequel of his command the elephants of the enemy act as he predicted:Footnote 41 “The elephants, at last worn out by wounds, rushed upon and overthrew their own men, and those who had guided them were hurled to the ground and trampled to death by them. And now like cattle, more frightened than dangerous, they were being driven off the field of battle….”

There is nothing like this in Diodorus and Arrian. Both confirm that Alexander addressed the reluctance of the army at the Beas, but without the argument from contempt of war elephants. Comparison with Arrian on the battle with Porus, in my judgment, gives no clear reference to the “greater harm to one’s own side” theme, but rather, it emphasizes how the action of the Macedonian cavalry wing, going around to the rear and pressing Porus’ cavalry backward, into the ranks of the elephants, created crowding. This would have been of help to the Macedonian infantry. In Arrian, the battle of Porus’ elephants with Alexander’s infantry is depicted as a long and drawn-out back-and-forth, not the greater harm to Porus’ own side that the Roman meme requires.

Comparison yields some confirmation. Arrian names three officers told off to lead the Macedonian infantry: two of them, Antigenes and Tauron, are the same as in Curtius, but for the third of Curtius (Leonnatus), Arrian gives Seleucus. Both are drawing upon a common source here, but their readings differ on this one name. It makes good sense that Seleucus would have commanded the infantry against the enemy elephants at this singular battlefield encounter, which could have motivated the very high estimation of the elephant he shows after Alexander’s death. His enthusiasm for the elephant of war is displayed, and was rewarded, throughout his reign, and he bequeathed it to his successors.

One other item from Curtius’ account of this battle is worth considering, and this is that Alexander used the elephants he had previously acquired to prepare the infantry to attack the feet and trunks:Footnote 42

As a result, the shifting battle, as they now pursued and now fled from the elephants, prolonged the undecided contest until late in the day, when with axes—for that kind of help had been prepared beforehand—they began to cut off their feet. With slightly curved swords called copides, they attacked the brutes’ trunks. And their fear left nothing untried, not only in dealing death, but also in new ways of making death itself painful.

This is plausible on the face of it, but it is uncorroborated and sounds very like a Roman approach to elephants of the enemy. Its rhetorical effect is to give a reason for Alexander’s elephant-collecting propensities that does not presume his intent to use them in battle.

Ancient historians writing in Greek and Latin felt themselves free to render speeches according to the canons of rhetoric rather than submit slavishly to the very words of the speaker. In that way they differ from modern rhetoric, for which direct speech implies a contract with the reader that the exact words of the speaker are being delivered.Footnote 43 Curtius’ Alexander having a “poor opinion” of the Indian war elephant is an extreme interpretation, confirmed by no other of the surviving histories of Alexander, so that we cannot conclude that it comes from an early source. Moreover it is belied by the record of the care Alexander took to acquire elephants and an Indian staff to service them, and the efforts taken to conduct them safely from the valley of the Indus to Babylon. Scullard calls Curtius’ account “nonsense,” and he is certainly right.Footnote 44

Armandi: The Unreliability of Elephants Is a Fact of Military Science

Pier Damiano Armandi (1778–1855) was an Italian from a French family that had settled in Italy in the seventeenth century. He attended the Military School of Modena and entered service in the artillery and soon found himself among the Italian allies of Napoleon’s Grand Army, with whom he participated in many notable battles. He had a role in Napolean’s return from Elba during the Hundred Days. He also had a reputation as a scholar and was asked to direct the education of the sons of Louis Bonaparte, the emperor’s brother.

The book on war elephants was published later, during a period of exile in Paris. Armandi had been appointed minister of the army and navy under the revolutionary republic of 1831, called United Provinces of Italy, which was quashed by the Austrian army less than two months later—his appointment lasted only from 2 March to 26 April, after which he fled to Paris. He gave a lecture on the war elephant in classical antiquity to the Academy des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. It was well received, which encouraged him to publish. In the book he described himself, among other things, as a retired colonel of artillery (later rising to general).Footnote 45

Several aspects of this life are evident in the work. One of them is a tendency to think of the military action of the war elephant by means of the physics of artillery; that is, the mass of the elephant, thrown into motion, is transformed into military force—elephant ballistics, we could say. While in our own time it is common to liken the war elephant to the modern tank, Armandi more than once likens it to artillery. Another tendency is an emphasis upon military science in Greco-Roman antiquity. He refers several times to ancient works on tactics and gives his own detailed and numerous analyses of battles by the ancient writers, from which he reconstructs the tactical use of war elephants. Finally, the Italian component in his formation made him acutely conscious of the present aliveness of the classics. He identified with ancient Rome and with its army, which he called the greatest in the ancient world.

Armandi’s project is to repair an absence in the historical records of the ancient world: the lack of what he calls didactic works upon the war elephant. What he is alluding to he states simply, but opaquely; the argument marches on, and one may miss the importance of it. The missing object of study consists of ancient works of military science, didactic works concerning strategy and tactics, specific to the use of the elephant: the very lacuna previously noted, as mentioned in the Tactics of Arrian. Not only does Armandi cite such works as have survived from ancient times, notably those of Polyaenus and Arrian, but he is referring to the fact that these works, though written in Greek, belong to the time of the Roman Empire, and have displaced earlier works that included analysis of the use of the elephant in war, coming from the Hellenistic states. The earlier works had become obsolete with the Roman refusal of the war elephant at the outset of the empire, after Rome defeated the Hellenistic powers and renounced, finally and definitively, the use of war elephants, and subsequently the works themselves were lost. This renunciation is the single most important event for Armandi’s book. His stated purpose is to repair the lacuna, but his unstated one is to establish, by means of military science, that the Romans were right to put an end to their use of the war elephant.Footnote 46 This momentous decision, at the moment when the entire Hellenistic-period field of elephant-using states had fallen to Rome, is the key to the structure of the work as a whole.

Roman refusal of the elephant in war governs the division of the work into three books.

Book I lays the foundation for the restoration of the lacuna, by giving analyses of battles involving elephants from the time of Alexander and the Hellenistic period, from which Armandi infers the strategic and tactical principles of Hellenistic use of the war elephant. It ends with a chapter on a crucial turning-point: “Romans decide to use elephants” (Book I, chapter 12).

Book II examines the organization of war elephants and the “expedients invented by the ancients to resist elephants,” the training of men and horses against elephants, plus the various principles of their use and of defense against them, that can be drawn from the battles analyzed in Book I. It concludes, in the tenth chapter, with the greater turning-point: “The Romans renounce elephants, and the use of them was abandoned in the West.”Footnote 47

Book III, the shortest of the three, brings the story up to modern times, which is to say, the age in which the diffusion of gunpowder-driven warfare pushed the elephant from the center of the battlefield to its margins. It begins with the reappearance of elephants in the army of the Sasanian Persians, whose realm abuts the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire, so that the Roman soldiers, having had no elephants on their side for centuries, had to face anew the terrors of the war elephant, the Persians deploying elephants and drivers from India. It continues with examination of the elephant in South and Southeast Asia. Although it is the shortest of the three parts, in many ways it is the most significant, for it uses the features of the modern era—foregrounding European military innovations in field artillery, musketry, and close-order infantry formations—and the European making of Asian empires in elephant country, as the final reveal of the military history of the elephant.

The work is very detailed and extensive, with specialized material consigned to appendices, notes, and descriptions of coins pertaining to this history. It is an excellent work, with many valuable insights about a lost world reconstructed by an experienced practitioner of military science in the Napoleonic age. It issues from a mind well-equipped to interpret the military use of elephants in antiquity.

It is also a work inspired by the success of Western armies forming new empires in Asia. For Armandi, Military Science (he sometimes puts it in upper case, signaling the importance in which he holds it) belongs to the West, and the West was in course of using military science in the making of new political structures on a grand scale around the globe.

Armandi’s argument reaches its completion in this passage:Footnote 48

It is not astonishing, finally, that barbarous nations, to whom the true principles of the military art were unknown, placed unlimited confidence in their elephants, as that which they had placed in chariots, in the noise of the instruments, in the glamor and richness of their costumes, and in all that which was proper to strike the senses and stir the imagination. It was to substitute appearance for force, and mask a true inferiority by vain ostentation. But the great captains of antiquity, accustomed to count only on the soundness of their troops, were always suspicious of these dangerous auxiliaries [elephants], of which we have seen that their ferocity could derange all combinations of military science, and put at hazard too considerable a part. In truth, Alexander showed that inquietude, at his arrival in India, on the effect which the elephants could produce upon his army; but once he appreciated with his own eyes the real importance and danger, he recovered himself and thereafter he had little to do with these animals as with those who used them.

A civilizational frontier is being marked out here, and theorized, with science and reason on one side, and appearance and ostentation on the other. But though it appears new, it is a modern iteration of Curtius’ scorn for the ruler of India and the politics of excess. What is revealed by European military success in this conception is the superiority of its military science. As we shall see in the next section, this prepares the way for, or at least is congruent with, the conception that science itself is European in origin and yet universal in validity. “Oriental excess” and mistaking shadow for substance are essential ingredients for the making of it. Although Armandi does not say so, he implies that Alexander succeeded in Asia, and modern Europe surpassed Alexander, completing the “proof” of European superiority which Curtius and his contemporaries had begun.

For all the greatness of Armandi’s work, and the central importance of his project to restore the lost tactics of using the war elephant in the Hellenistic period, it is deeply flawed in this central finding. For if Alexander had contempt for the Indian war elephant, why were his own officers, above all Seleucus and Ptolemy, so enthusiastic for elephants, and so successful in their use? And what do these glaring exceptions do to his argument that the great military captains of antiquity in the West, of whom Alexander and Caesar are the examples named, did not trust the elephant? In truth, Armandi’s project of restoring the lost tactics for elephants by inferring them from the accounts of battles is a good one but fatally wanting, for those accounts of battles have first to be scrutinized for anachronisms coming from later Roman policy. Armandi shows no sign of recognizing the possibility, when inferring the tactics from surviving descriptions of battles, that those descriptions may be contaminated in the retelling by the conviction to which the Romans came, that elephants posed a greater danger to their own side. The likelihood is great that Armandi’s project, which has no method of detecting and accounting for this kind of anachronism in the sources from which he reconstructs the lost tactics of using elephants, draws a proof from material which has been salted beforehand with the very thing that it is looking for.

Now, it is evident that an elephant in battle may lose its mahout to death or some other hazard of battle, and do damage to anyone in his immediate vicinity, which will often be those of its own side. But the Roman policy was at heart comparative in nature, implying that the danger to its own side not only exists, but is greater than its danger to the enemy, under conditions then obtaining, of the training of drivers, for example, and the size and species of the elephants in use, on both sides; and because this finding is already contained, at least in part, in the evidence from which it is drawn, it rests on circular reasoning.

Benedict: The Unreliability of Elephants Is a Fact of Elephant Physiology

The long afterlife of the Roman meme of “elephants a greater danger to their own side” is now so deeply embedded in the scholarly literature, and so unshakable, that it is often nearly invisible. I offer three remarkable instances. The first of these is Benedict, whose fascinating study of elephant physiology repays a close look, because his authority lies not in military matters or the history of classical antiquity, but in the natural sciences, as an investigator of nutritional metabolism among various species of animals. As such, Benedict is a scientific authority who transforms Armandi’s truth of European military science into a truth of European natural science. Two subsequent examples by later scholars of high repute in different fields will serve to indicate how taken-for-granted the Curtian argument has now become, thanks to the path of transmission it has taken over the last two millennia. Scullard’s demonstration that Curtius’ view of Alexander is nonsense failed to make headway against the prevailing opinion.

When Francis G. Benedict published his 1936 book on the physiology of the elephant he was director of the Nutrition Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C. The project was to establish the elephant’s basal metabolism. The Nutrition Laboratory pursued the comparative study of metabolism among animals of various species, cold- and warm-blooded, and especially at the extremes of bodily size, as the best way to advance the interpretation of the nutritional physiology of humans. While the physiology of mammals from the mouse of 20 grams to the Percheron horse of 750 kilograms had been attained, it would be impossible to estimate with any accuracy the metabolic profile of the elephant, at 5,000 kilograms, from that of the horse, since it was so very much larger. Accordingly Benedict, who was eminently qualified by training, and could draw upon the resources of the institution which he directed, undertook the pioneering study of elephant nutritional metabolism, which became a classic. For our purposes it is significant that he cites both Curtius and Armandi as the authorities from which he takes the truth that elephants are a greater danger to their own side in war.Footnote 49

As we see in the epigram at the head of this essay, Benedict reproduces the Roman meme as a fact of natural science. On the other hand, Benedict discusses his own direct observation, and his interviews of elephant managers; but, when examined closely, we find the results do not support the supposed facts of elephant temperament.

To establish the basal metabolism of the elephant Benedict designed an isolation chamber fitted with apparatus to measure incoming and outgoing gases. The apparatus included a specially made device into which the elephant had to put the end of her trunk. The whole process clearly required a trained elephant, one that was especially tractable; for all practical purposes it would have to have been female and Asian, as were most circus elephants in America.Footnote 50 The elephant Benedict was able to borrow for the purpose was immune to sudden excitement because she had considerable experience of street noises, elevated trains, and fire engines, having lived in the city for a long time.

In one particular, however, she showed great excitability and distrust of what was going on. Since she was chained both by a front and a hind leg, it was impossible for her to turn her entire body quickly to see what was going on behind her. The result was she had a tendency to become restless when any unusual action was going on outside of her field of vision, that is, toward the rear. In general she did not like to have anything going on that she could not see. Whatever she could actually see in front of her did not frighten her, but sudden movements behind her that she could not see troubled her.

This is most interesting. What he calls “flightiness” in circus elephants perhaps has its causes in the eyesight of the elephant and a difficulty of seeing behind it due to the combination of its wide body and the custom of chaining it closely in a limited space.

Reporting on the management of elephants in American circuses, Benedict says, “With the Ringling herd on tour, two keepers are on continuous watch all night, directly in front of the elephants so that they can see the entire line of thirty-four.”

Generally no trouble is expected, but as Doherty [an elephant manager with the circus] commented, if a zebra broke loose and came running into the elephant section, the elephants would become so startled that they might pull away their stakes and cause much damage. Indeed, the presence of any strange animal, no matter how small, is apt to cause disturbance. A strange dog barking, or any other small animal, usually will excite one of the members of the herd, and she in turn tends to excite all the others.Footnote 51

An unfamiliar sound, then, needs to be added to the list of things that provoke unruly behavior among captive elephants.

A thunderstorm was the topic of a recollection about another group, the Barnes herd.Footnote 52 Shortly before their afternoon performance a heavy electrical storm came up, with lightning and thunder. By order of McClain, the head elephant man, the elephants were unshackled and massed together, side by side in solid formation, with a man at the head of each animal with his hook. At each end of the line was a non-temperamental elephant which, experience had shown, was not apt to stampede. If any flighty animal started to stampede, its space for action was limited and the docility of the others, as a whole, would hold it in check. Although the head keepers and the individual keepers were obviously anxious and feared a possible stampede, on this particular occasion the animals were apparently unaffected by the crash of the thunder or by the lightning and ate their hay with the greatest placidity.

This is interesting in a different way. It appears that a thunderstorm was sufficiently familiar that it caused no stampede. Furthermore the flightiness of a few could be controlled by taking advantage of the non-flightiness of elephants accustomed to the source of disturbance. Benedict allows for individual variation of elephants in his narrative about the tendency to stampede, which undermines the main contention. It appears that the elephant keepers, holding the hooks—the American circus variant of the Indian ankush—are expecting the instruments to perform their proper office, namely, to restrain the elephants.

We may reasonably conclude that flightiness of elephants arises when they hear something they cannot see because it is behind them, or hear a noise that is unfamiliar; but when it is as familiar as a thunderstorm, or when it concerns loud noises to which an elephant has become familiar, it does not arise; and the ankush can cope with it when and if it does. Benedict’s personal observations and inquiries do not really support his Curtius-inspired reading of the historians.

Now all animals have an inhering tendency toward fight or flight under certain circumstances, so that the question of the flightiness of elephants is by implication a matter of degree and context. The susceptibility of elephants to panic and flight, the Roman meme implies, is greater than other animals—war horses, for example—but the comparison is not made explicit. The non-discussion of this implied comparison seems to say that the fact is so well established as to need no demonstration. The capacity of horses to be spooked and to stampede, or zebras, perhaps, is somehow less than that of the elephant, Benedict seems to be saying, by not saying it. But consider what Baynham has to say on the topic:

All horses, being the highly reactive animals that they are, may display defensive behaviors like rearing, bolting, bucking, kicking, biting or striking, if they perceive a sufficiently threatening or provocative stimulus. Even horses like those of the Queen’s Household Cavalry, Italy’s 4th Carabinieri Mounted Regiment, Canada’s Mounties, or horses employed by mounted police around the world, which have been de-sensitized and extensively trained to ignore strange or loud stimuli, have been known to react in an unexpected and sometimes explosive manner.

I cannot help saying, against this deeply interesting study, that Benedict’s own testimony does not fit the Roman testimony he cites, drawing on the very passages of Armandi I have reproduced in this article.Footnote 53

Let me end with two more examples, of eminent scholars from different fields, who depart from Benedict in being very cryptic, as examples indicating a belief that the unreliability of the war elephant has become an acknowledged fact.

Juliet Clutton-Brock of the British Museum, well-known authority on the domestication of animals, writes of the elephant,

Despite such a show of strength [at Gaugamela] Alexander won this decisive battle, and so it was to be in future battles, for elephants were not made for fighting human wars. Despite this obvious fact both Indian and African elephants were frequently used for front-line attacks as well as for carrying baggage. The use of tamed African elephants by the Carthaginians and by Hannibal in the Punic Wars against the Romans is very well documented and has been admirably described by Scullard (Reference Scullard1974). The short-term success of the Carthaginian “cavalry” was probably due as much to the effect of surprise as to the power of the elephants for the one great disadvantage of an elephant in war is that if assailed by a multitude of arrows it will very sensibly turn round and go backwards, thereby inflicting worse damage on its own army than on the enemy. Footnote 54

I believe “not made for fighting human wars” is an implicit contrast with the war horse, domestic animals bred for qualities desired in war, such as those used by the heavy cavalry of knights and horses in shining armor of medieval Europe. But what the Indians prized in the war elephant was a character of wild elephants, their combativeness when in musth. The Indians understood the characteristics of their elephants and had confidence in being able to control them in most circumstances.

Richard Stoneman, notable classicist and author of a fine book on the Greek experience of India, is another example of elephant skepticism. He puts the battle between Alexander and Porus in three words: “cavalry trumps elephants.” The Roman meme could not be put more succinctly.Footnote 55

Follow the Elephant

Armandi reinforced Curtius, and restated, at length and in the language of contemporary military science, the Roman skepticism about the Indian war elephant. So persuasive was his argument, made with such evident mastery of detail, that it closed the book on the topic. A century later, Benedict turned this evidence into a fact about elephant physiology, so thoroughly that the unreliability of the war elephant became a trope and no longer needed any argumentation to support it.

A measure of its success is that no book-length survey of Armandi’s topic appeared for over a hundred years, until the work of H. H. Scullard (Reference Scullard1974). As previously mentioned, Scullard contested Curtius’ view, rightly in my judgement, but by this time skepticism about the war elephant was taken for granted. Scullard failed to change the prevailing view.

Scullard covers much the same material as Armandi, within the same bounds of time and space. There are many parts of his book that hit the same thematic notes, doubtless because of the similar framing of the topic. But the interpretation by Scullard is quite different. Partly this is because his book does not announce itself as a military history of elephants as does that of Armandi, but as a general work for the reading public about the elephant, in all aspects, in the Greek and Roman worlds. Military engagements are of course prominent, because the elephants in question were most of them war elephants, and Scullard’s work therefore is like Armandi’s in including descriptions of battles. Perhaps more important is that Scullard does not have Armandi’s project of restoring a lost body of Hellenistic period elephant tactics by inference from battle accounts. Scullard’s frame is more descriptive, and he uses a more commonsense manner of argumentation.

Scullard calls Curtius’ report of Alexander’s contempt for elephants nonsense, and invokes against it the hard-headed Seleucus, whose success with the five hundred elephants he acquired from Chandragupta is not in doubt.Footnote 56 There is no comprehensive examination of Curtius, to be sure, and Scullard does not drive home the point about Seleucus, who is, in truth, an example, indeed the prime example, of a large class whose good military judgment is implicitly denied by Armandi. Both rest their opposing evaluation of the efficacy of the war elephant upon the “great captains of antiquity,” but Armandi’s conception of that exalted body has no place for the great generals of the elephant-using powers of the Hellenistic period, beginning with Seleucus. In these few words, I contend, Scullard is right, while Curtius, and Armandi, too, much as I love his work and find it rewarding—are wrong.Footnote 57 But Scullard does not identify the critical matter as anachronism in the surviving evidence.

Scullard’s book, however, is not the end of resistance to the Roman meme.

We find the missing note of anachronism in the sources explicitly articulated and tentatively offered in an excellent article on the matter by Michael B. Charles.Footnote 58 He says, “It is possible to detect, in the words and actions attributed to Alexander, a hint of anachronistic rhetoric, written from the perspective of sources equipped with the hindsight resulting from the centuries of Mediterranean elephant warfare experienced thereafter. It is therefore difficult to rely on such sources as evidence for fourth century BC views on elephants.” He has “an inkling that the words that Curtius puts into Alexander’s mouth, which one observer characterizes as ‘nonsense’ [Scullard, of course], were influenced to some degree by centuries of later elephant warfare. If so, it could represent a dramatic literary insertion on Curtius’ part….”

Exactly so. This identifies very well what is needed to achieve solid ground on the war elephant in Greek and Roman antiquity, namely an examination of the sources from which the lost Hellenistic works on tactics can in some measure be reconstructed, keeping an eye singular for anachronism, coming from late Republican Rome.

This is a great advance on Scullard, who pronounces the speech Curtius attributes to Alexander nonsense, but does not explain it. Charles accounts for the production of this nonsense as a “Mediterranean” view formed in later times—as an anachronism, in effect what I am calling the Roman meme.

Charles determines that Curtius’ history of Alexander is unreliable on this point. But we can use this idea to take us further. To understand the Hellenistic period, including its all-important India connection, we need to complete the program of Armandi, of restoring the lost Hellenistic elephant tactics as best we may from the texts that survive. But we need to improve the program by first looking closely for anachronisms of this kind. This is the element whose absence vitiates Armandi’s otherwise magnificent work.

We need to follow the elephant, not as a symbol or a literary trope, but as a living being of superlative size, with all the demands its magnitude makes upon the exchequer through the keepers, drivers, trainers, and physicians needed to keep it battle-ready, at Pataliputra of the Mauryas, at Apamea of the Seleucids, and at Berenike of the Ptolemies. It will lead us to greater understanding of the actual workings of the large states that undertook the steep costs of using them in their armies.