No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Rhythm, Metre, and Black Magic1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1942

References

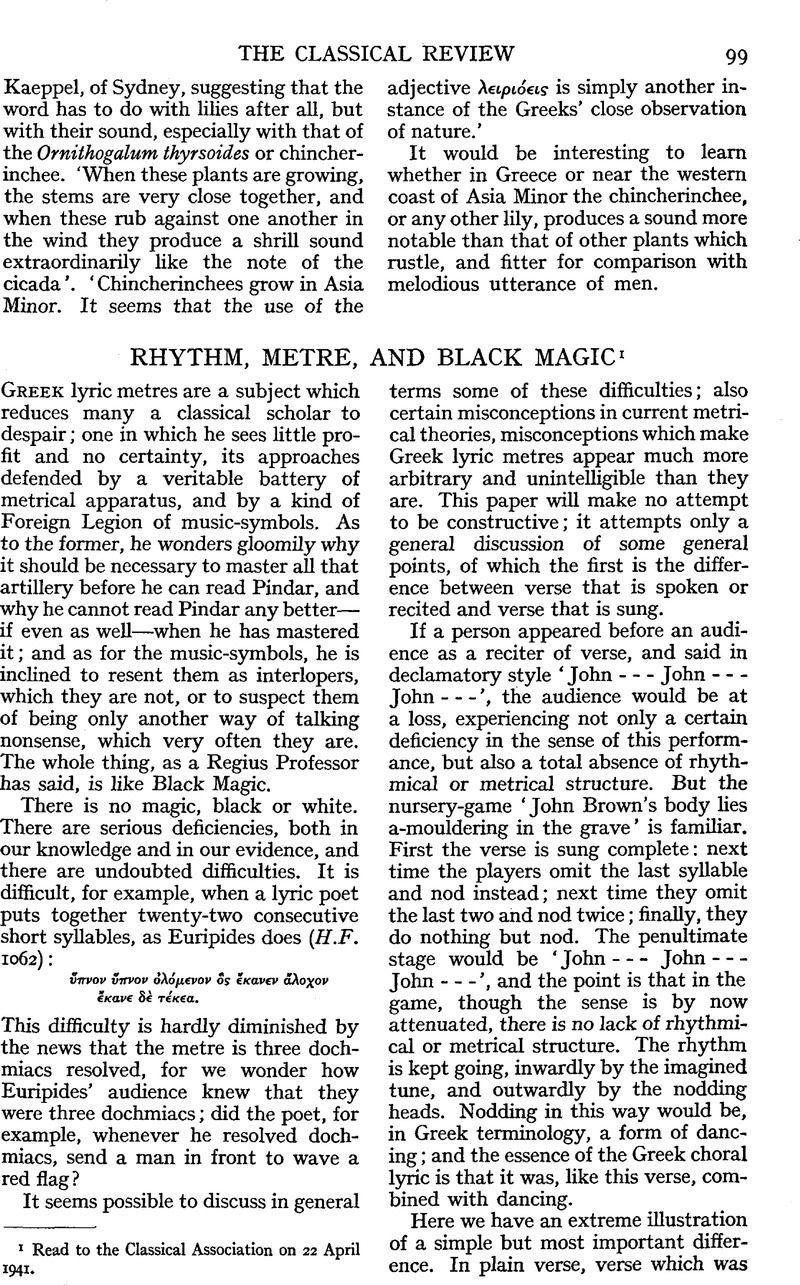

page 101 note 1 Or, if the reader prefers it, ![]() . This rhythm too is just as effective (though no longer pictorial) in the antistrophe.

. This rhythm too is just as effective (though no longer pictorial) in the antistrophe.

page 101 note 1 Denied, that is, for poets earlier than Euripides (Oresteia, ii. 335).

page 102 note 1 See Aristides Quintilianus, p. 40 (Meibom): ![]() .

.

page 103 note 1 The Headlam-Thomson theory, which makes no attempt to measure, is not a system of metric at all, strictly speaking, but a descriptive rhythmic.

2 Traitè de mèlrique grecque, p. 317.

page 104 note 1 P. 97 (Meibom).

2 Who were of course in fact the same people.

3 I may perhaps mention here a point for which there was no time when this paper was read. It is this, that in favourable circumstances we can check, with certainty, the extent of these rests; e.g. the strophe of Pindar, Ol. I is analysed by Schroeder into three periods of 23, 23, and 22 theses respectively. Asked to admire the symmetry, I refuse: I can see only a deliberate eccentricity in these figures—but Pindar was not an eccentric. Obviously, what Pindar designed was not 23–23–22, whichis artistic nonsense, but 24–24–24, which is sense. In the syllables of thetext we have not got Pindar's complete rhythm: four ‘bars’or ‘theses’ are missing; but it was only this complete rhythm that Pindar had any desire to make symmetrical. And, now that we knowhow much it is that we have to measure here, we find another control for our metric: for example, the last four verses of this stanza must obviously be not 6–5–6–5 but 6–6–6–6. A system of metric which makes this impossible is itself impossible.

page 105 note 1 How many of the six are sung and how many are ‘rests’ does not concern us.

page 105 note 1 When this paper was read, some hecklers maintained that the rhythm is ‘anapaestic’, not ‘dactylic’. The point is not essential to the present argument, which couldbe restated in anapaestic terms; but I think the second limerick quoted isstrongly in favour of the ‘dactylic’ view.— have been unable to discover the authors of these verses, and apologize if copyright has been infringed.

page 106 note 1 Here, for example, is the opening of the Midias, and the scansion thereof (admittedly a hiatus has to be overlooked):![]() .

.

page 106 note 2 To simplify the argument I say nothing of quintuple. Four-time of course is duple.

page 107 note 1 This equality in dipodies has no relation to our equality between bars. Our equal bars reflect our equidistant stresses: the equal dipodies do not produce equidistant stresses (or arses), nor anything like it.

page 107 note 1 Greek theory recognized, what the modern musician knows, that the size of the rhythmical unit, whether monopody, dipody, tetrapody (cf. ![]() time), is very much a matter of

time), is very much a matter of ![]() , tempo. Frag. Paris. §12

, tempo. Frag. Paris. §12 ![]() . To give an illustration: both the National Anthem and ‘Daisy Bell’ are in some sort of three-time(trochaic); but the time of the Anthem goes slowly, and the accent on the first, fourth, seventh‖beats is equal; but ‘Daisy’ goes more quickly, and the accent on 1 and 7 is stronger than that on 4 and 10. That is, the Anthem goes

. To give an illustration: both the National Anthem and ‘Daisy Bell’ are in some sort of three-time(trochaic); but the time of the Anthem goes slowly, and the accent on the first, fourth, seventh‖beats is equal; but ‘Daisy’ goes more quickly, and the accent on 1 and 7 is stronger than that on 4 and 10. That is, the Anthem goes ![]() , 1 2 3 1 2 3,‘Daisy’

, 1 2 3 1 2 3,‘Daisy’ ![]() ,1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6.

,1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6.

page 108 note 1 Meibom, p. 292.

2 This is an exaggeration, but not a gross one. The pure trochee is in the ![]() ; the ‘heavy’ trochee not far from it.

; the ‘heavy’ trochee not far from it.