On 17 November 2017, a few weeks after the conclusion of the 19th Party Congress, the general Party branch of the Science and Technology Association in Beijing's Pinggu district 怀柔区 came together for a special event.Footnote 1 To propagate the results of the 19th Party Congress and help villages with their poverty alleviation efforts, the association's Party branch conducted a “Thematic Party Day” (zhuti dangri huodong 主题党日活动, TPD hereafter) in Sidaowopu 四道窝铺 village in the Baoshan 宝山 township. Participants included all members of the Party branch, some local village Party members and others drawn from the “masses,” totalling 40 individuals altogether. The event comprised four parts. First, there was a Party class during which the deputy director of the association gave a lecture on the spirit of the 19th Party Congress. Then, there was a “listen to needs, seek development” symposium. Here, two previous projects were assessed and future directions for poverty alleviation discussed with the local Party branch. Third, leading cadres were paired up with each other. Members of the association exchanged contact cards with people chosen by the village Party committee and discussed their individual needs. Fourth, under the slogan of “science and technology going to the countryside, benefiting the people's livelihood,” the TPD participants distributed over 300 leaflets containing information on the benefits of science to agriculture, general scientific knowledge and intellectual property law. They also answered ten questions from the villagers. The event then concluded, and participants returned to the city.

In the last few years, events like this have become commonplace in China. TPDs have become a fixture of Party branches’ organizational life and a major way to manage the Party's members at the grassroots. As the CCP's “nerve-tips,” Party branches organize grassroots Party members and manage ordinary Party members. In 2019, China's 92 million Party members were organized in over 4.1 million grassroots Party branches with an average of 22.3 Party members each. Occurring monthly, in theory over 49 million TPDs were held by Party branches in 2019; they were also formally codified in the “Party branch work regulations” (Zhongguo gongchandang dangzhibu gongzuo tiaoli 中国共产党支部工作条例) of October 2018.Footnote 2 Linking the Party centre to its grassroots, their ubiquity and importance suggests that TPDs are an ideal proxy to understand how the CCP relates to its ordinary Party members.

TPDs reflect how the Party centre understands, mobilizes and manages its own members. Party branches mobilize their members, choose themes reflecting the Party's priorities and carefully manage participants and appearances. In the case above, the Party branch selected a variety of activities and required all its members to participate in the event. Its counterpart was the village Party committee, which selected ordinary people for the members to interact with. To frame this event, the Party's historical legacy of “going to the countryside” (xia xiang 下乡) was invoked. Through practices and language, TPDs operationalize ideology to control the Party's grassroots and, as such, are the observable “materialist” manifestation of rhetoric and symbols wherein, in the words of Louis Althusser, ideology is “inscribed in ritual practices.”Footnote 3 An analysis of TPDs therefore reveals how the Party dominates the broad swathes of its grassroots members by prescribing practices to socialize Party members and reproduce the CCP's ideology.

This article builds on two strands in the literature. First, the role of organizational life and its practice. For example, Doak Barnett describes the Party's organizational life in the Mao era as mainly consisting of the dissemination of policies from the centre, discussions, criticism and self-criticism, and political study.Footnote 4 Franz Schurmann also sees it as “talk, discussion, group interaction, criticism and self-criticism.”Footnote 5 Finally, James Townsend paints group activities as “a universal form of political organization,” with individuals meeting regularly for “well-organized and purposed activities.” Its most important iteration is the “political study group,” which “is a regular feature in Party life.”Footnote 6 While political study remains critical under Xi Jinping 习近平, organizational life has evolved significantly. According to the “Party branch work regulations,” there are five crucial components to be organized. First, there are the monthly Party branch committee meetings and quarterly meetings of all Party members, in addition to monthly Party small groups and an annual Party class. This arrangement is called “three meetings, one class.” Second, there is an organizational life meeting, which should take place once a year. Third, there should be an annual “democratic assessment” of all Party members. Fourth, branches are expected to organize an annual “heart-to-heart-talk” among Party branch members to exchange opinions. Lastly, there should be a monthly TPD.Footnote 7

TPDs are well publicized and highlight a major difference with the Mao era. While the importance of study is a given in TPDs, ideological education is multifaceted. Rather than solely relying on the recital of policy documents or speeches, activities are more diverse, integrated and targeted. Thus, the Science and Technology Association's TPD, described above, featured multiple activities and was conducted in a local village. This TPD required the intricate planning and involvement of many to organize scheduling, transportation and budgets as well as the preparation of speeches and information leaflets. More importantly, the study element took the form of a field trip to learn about local problems and educate locals. The objectives are clear: to bridge the gap between the centre and the grassroots, urban and rural, and to integrate the association's Party members within the local community. The flexibility that allows TPDs to be tailored to suit Party branches’ situations indicates that they are a valuable tool for organizing the Party's grassroots members.

Second, another major strand in the literature focuses on the Party's relationship with other entities. For example, Bruce Dickson writes about how the Party co-opts entrepreneurs.Footnote 8 Others have examined the impact of Party building in the private sector, state-owned enterprises or society.Footnote 9 Likewise, Patricia Thornton analyses the Party's advance into the “third realm” of non-governmental entities, arguing that Party building diluted the Party's “effectiveness as a vanguard organization” while exerting influence over NGOs.Footnote 10 In these examples, the Party is often understood as an “organizational emperor” that manipulates different social groups.Footnote 11 While immensely insightful, these works examine the Party from the vantage point of its dichotomous relationship with other actors.

My analysis refocuses this analysis in a major way. While the aforementioned authors focus on how the Party has reacted to the emergence of outside forces, I look at how the Party's reaction to these external actors has impacted its internal organization and the perception of its grassroots members. Hence, instead of concentrating on the horizontal level where a local Party organ interacts with local organizations, I look at the vertical plane at the interaction between the centre and its basic level.

In this article, I show that TPDs are rituals of control deployed to enhance and reproduce the Party's authority in the eyes of grassroots Party members. This claim has two parts. First, TPDs have become increasingly standardized and integrate different activities. Second, I demonstrate that TPDs aim at strengthening the link between grassroots Party members and the Party as an organization and the Party centre, rather than the local level or non-Party organs. However, the Party centre's control over the grassroots is far from absolute. Rather than blindly complying, Party branches are selective, emphasizing different ideological values and activities, while neglecting others. Assessing TPDs, therefore, can help us to gain a better understanding of how grassroots Party branches produce power and how they consume and subvert practices and symbols.

I have chosen Beijing as a study site because its proximity to the central leadership means Party branches are subject to greater scrutiny and thus they would exert greater effort to organize events. At the end of 2018, Beijing had 2.22 million Party members organized in 95,000 Party branches, with an average of 23.4 Party members per branch.Footnote 12 Summaries of TPDs were found online on local district government websites and downloaded. This online survey produced a sample of 1,408 TPDs conducted from 2015 until the end of 2020. The length of event summaries varies significantly, from just a few lines to multiple paragraphs and detailed descriptions of activities. Since local authorities upload only the “best events,” this sample represents a critical or crucial caseload, offering a full repertoire of activities that other localities can draw on.Footnote 13 It is, then, accepted with relative confidence that their modus operandi reflects the general operation of TPDs elsewhere in China.Footnote 14

Next, I frame TPDs as rituals to control grassroots agents and look at the formation of ritualistic activities. Then, I further disaggregate the TPD activities and probe how they integrate the individual with the Party in general, the Party centre, the locality and external entities. Finally, before concluding, I discuss the problems associated with the development of TPDs.

Rituals of Control

In general, there are two ways in which the Party controls lower-level agents. The first is the nomenklatura system and the formal hierarchy through which directives trickle down from the Party centre to the provincial and municipal levels and eventually to the grassroots.Footnote 15 From the centre's perspective, the necessity of the middle strata is both a blessing and a curse. While having a middleman substantially reduces the monitoring costs of grassroots agents and enables “guerilla policy-making,”Footnote 16 it also generates opportunities to ignore or (mis-)interpret central directives.Footnote 17 Hence, since grassroots officials are dependent on their direct superiors for promotions, they often have little choice but to defy central policies. This system is complemented by a disciplinary mechanism that punishes officials’ deviations.Footnote 18

The second means of control is ideology. As Kenneth Lieberthal notes, exposure to ideology leads to high sensitivity “to themes and priorities articulated by the Center.”Footnote 19 Through the adoption of slogans or formulations, ideology can play a role in understanding policy. In the ideal situation, as Martin Whyte argues, the desired result transcends mere compliance and people “enthusiastically and creatively support” higher directives.Footnote 20 This indicates two crucial differences as opposed to the first form of control. First, if the grassroots are guided through ideology, there is no need for the middle levels – ideology is overwhelmingly controlled centrally, and it is only the centre that bestows credence and authority to slogans. Second, control through ideological slogans happens on a spectrum. While in its extreme version, Party members actively find ways to translate precepts into action – at a minimum even disinterested engagement produces a rudimentary understanding of central priorities and slogans. Ideology, then, in the words of David Apter and Tony Saich, narrows the “space for differences in views” between the centre and the grassroots.Footnote 21 If this is expanded to the Party in general, even passive exposure to the Party's propaganda produces an atmosphere of consent and highlights the strength of the system, which increases the costs of dissent.Footnote 22

The integrative nature of ideology has been widely noted. In his classic study on ideology and utopia, Karl Mannheim argued that ideology serves to preserve a certain order and legitimize a political system.Footnote 23 However, as Göran Therborn recognizes, the linking of ideology and legitimacy is problematic. He notes that legitimacy is often portrayed as a possession: either a government has legitimacy or not.Footnote 24 This creates issues for how ideology is understood. If people obey either because of “normative consent” or “physical coercion,” then there is little room for investigating how ideology operates as a technology that is constantly communicated and reproduced. As such, it is situational, being received, interpreted, accepted, rejected or transformed by individuals or groups. Building on Althusser, as Therborn argues, this process happens in ritual.Footnote 25

“Standardized human activity” – rituals – are therefore critical for the integration of values and the reproduction of a political order.Footnote 26 Distinguishing between secular and religious rituals, Émile Durkheim stresses the function of ceremonies to reaffirm a society's unity.Footnote 27 With regard to political rituals, Murray Edelman notes that they involve their “participants symbolically in a common enterprise.” Here, similarities are accentuated, and differences screened out, to fix “patterns for future behavior.”Footnote 28 While rituals are important in all political systems, the dominance of Marxism-Leninism makes them more pervasive in Communist societies. For example, Christel Lane notes how Soviet rituals entered “the life of every Soviet citizen during various stages of his life and the calendric cycle.” In contrast, it is comparatively “easy to avoid participation” in the West.Footnote 29 Western countries usually lack a coherent ideology that has a claim to structure the entirety of social relations. This is in contrast with the Soviet Union, where rituals were to “gain acceptance for a general system of norms and values” aligned with the leaders’ “interpretation of Marxism-Leninism.”Footnote 30 She contends that the pervasive dominance of ideology transforms rituals into forms of “cultural management” with a claim to define their citizen's relationships.

Especially in societies governed by a Marxist-Leninist party, rituals therefore have a strong governance aspect. As such, they have multiple characteristics. First, they link the individual to the collective.Footnote 31 As David Kertzer notes, rituals “socialize new members to the values and expectations that make up its culture.”Footnote 32 The most obvious example is the oath that signifies initiation into a party and the individual's integration with a broader organization and values. Second, rituals are infused with symbols that carry meanings. For example, the hammer and sickle stand for the tools of workers and farmers and the Communist Party's position as the vanguard of the working class. Likewise, the colour red stands for blood and revolution. Apart from being objects, symbols can also be verbal in the form of slogans, musical as in hymns, or even behavioural in the form of gestures. Similarly, people (socialist heroes or models), spatial configurations (memorials, buildings or squares), events (National Day), or even relationships (cadre and masses) can have symbolic value.

However, rituals are not mere top-down techniques of control. Echoing Therborn, Lane argues that rituals can only succeed if they are accepted by the people who perform them.Footnote 33 Participants adapt rituals and symbols to their own situation. Rituals are shaped by the Party centre, which prescribes certain practices, and by popular spontaneity at the grassroots. While their organization follows orderly patterns, the ambiguous aspects of rituals can always be reordered or manipulated. This indicates that in the performance of rituals there is considerable space for neglect, emphasis or omission. Rituals are then both a space for the centre's engineering of Party members and an arena where participants express their relationship to the Party.

In sum, rituals are aimed at changing people's perception of social reality to align it better with ideological definitions. As Børge Bakken argues, the Party views “ideological education precisely from its integrating and social control perspective.”Footnote 34 The integrative function of ideology, therefore, is combined with the integrative technique of the ritual. The standardization of organizational life and its codification in the 2018 “Party branch work regulations” suggests TPDs have become rituals to exact ideological control and reproduce language and symbols favourable to integration.

“Thematic Party Days” as Rituals

While the idea of the TPD precedes the 18th Party Congress in 2012, they were few and their function and format were largely unclear. In Beijing, TPDs have become more frequent in recent years. In my TPD sample, only 27 events were held in 2015; that number increased slightly to 38 in 2016, before jumping to 138 in 2017, 464 in 2018, 501 in 2019, and 240 in 2020.Footnote 35 This does not mean that TPDs did not exist before. An early event occurred in late June 2008, when the political-legal affairs commission of Beijing's Miyun district 密云区 held a TPD to study socialist legal concepts to “guarantee a peaceful Olympics.”Footnote 36 In both form and conduct, this TPD was indistinguishable from a normal study session.

Since then, TPDs have changed significantly. While they overwhelmingly include a study aspect, they combine different forms to expose Party members to ideological narratives. The Science and Technology Association case, outlined above, combined multiple activities involving the participants in different ways. For example, capping the number of participants at 40 meant that they could get to know each other and form personal relationships. Active exercises were complemented with passive ones — thus, a roundtable was scheduled after the Party class that conveyed central priorities. This was followed by a form of cadre “speed dating” during which contact details were exchanged. Finally, the propagation of science, technology and laws was a collective effort on behalf of all the participants. As such, it is possible to disaggregate the event into several activities with specific functions and aims.

In August 2017, Yanqing 延庆 district in Beijing conducted a highly integrated TPD.Footnote 37 While an extreme case, it is indicative of how TPDs are aimed at involving Party members and standardizing activities. The event's summary begins by explaining that the TPD was designed to “standardize Party life” and was held by the Party branch in the district's Environment and Sanitation Centre. The programme of activities included collectively taking the Party's oath, studying various chapters of the Party Constitution and paying membership dues. As the summary points out, these activities were conducted so that Party members would “stay true to our [the Party's] original aspiration” and relive the “belief and determination” they had when they joined the Party. Party members then attended a Party class and watched a presentation and short video on the life of Liao Junbo 廖俊波, a cadre who was awarded the title “National Outstanding County Party Committee Secretary” in early 2017 following his death at the age of 48 in a car accident in 2016. The presentation was accompanied by a class on “innovative thinking” and excerpts from Xi Jinping's work instructions for Beijing. Party members then toured an exhibition on heroes and martyrs in the district, studied the “CCP disciplinary punishment regulations,” which had been promulgated earlier that summer, and listened to a presentation on the goods deeds of the “moral model” (daode mofan 道德模范), Zhao Yuzhong 赵玉忠. The summary of the event concluded by pointing out that these activities “strengthened” the “sense of ritual” within the organization as well as the Party members’ “sense of mission.”

There are four issues to highlight here. First, there is no outside engagement with non-Party entities or the people; the TPD is a purely internal affair without any outside input. Second, the event relates to the Beijing locality and the Party in general. Xi Jinping's work instructions for Beijing fulfil a dual purpose: they link the district's Party members with the grander region of Beijing, but through the centre's lens. The study of the Party Constitution and the “Disciplinary punishment regulations” both reaffirm commitment to the centre and its policies, while also highlighting the “mission” of the Party. Third, other activities reaffirm the Party's general values. The exhibition highlighted the CCP's own historical narrative, and the stories of the model Zhao Yuzhong and former county Party cadre Liao Junbo were meant to highlight the attributes of an ideal Party member and cadre. These stories of self-sacrifice, ethical existence and tireless work for the common good therefore reflect broader Party values. Likewise, the payment of membership fees and review of the Party's oath reinforce the individual's commitment to the organization.

Finally, the TPD summary is candid about the need to standardize a “sense of ritual” to inculcate the Party members with the Party's “mission.” As Kertzer points out, standardization is one of a ritual's “most distinguishing features.”Footnote 38 What makes the TPD stand out is that it is both a ritual in itself and is also made up of rituals. Activities are categorized, codified on a list and are therefore interchangeable. The “Party branch work regulations” stipulate that TPDs should be held monthly and should arrange “collective study,” “organizational life,” “democratic deliberation” and “volunteering work” for participants (Article 16). Critically, they should not happen in an ad-hoc fashion, but must be organized and prepared for in advance. As a result, many Party branches submit yearly plans. For example, in the beginning of 2019, the education bureau of Fengnan 丰南 district in Hebei's Tangshan 唐山 published a document outlining its TPDs for the entire year.Footnote 39 The document includes a list of activities from which Party branches may choose. The list makes clear that “collective study” covers 12 types of documents, Party rules, and other forms of discussion and education; “organizational life” incorporates a review of the Party's oath, the “paying of membership dues” and can take five other forms; “democratic deliberation” includes budgetary issues, recruitment and yearly reports; and “volunteer services” offer the options of “scraping off advertisements,” “picking up trash” and helping with poverty alleviation. In total, the list contains 27 activities. The education bureau then caps this off by requiring each Party branch to produce a record of their TPD, which must include an outline of activities, the number of members who should have taken part, how many actually participated, and reasons for being absent. One copy of the record goes to the higher level, another to the education bureau, and a third is kept in the Party branch. Finally, each TPD is assessed internally by the members themselves – again, using a standardized form.

Not only are TPDs standardized but each activity becomes a ritual in its own right and is codified separately. TPDs can last an entire day, and so it is no surprise that 91 per cent of TPDs in the sample contain more than one activity. While this could be indicative of the successful institutionalization of TPDs, the ritualization of TPDs is still in its infancy and a continuing process. Some activities have been transformed into rituals successfully, while others have fizzled out. More importantly, success is uneven. This becomes clear when disaggregating the TPDs’ activities.

Multiple Paths to Integration

In the sample, 1,012 of 1,408 TPDs (72 per cent) involved some form of education. The focus on education is not surprising given its critical role since the founding of the CCP. However, this also disqualifies it as an explanatory variable: because it is ubiquitous, it is too abstract to explain the function of TPDs. Rather, “study” must be disaggregated.

Ideology defines the social relations of Party members and integrates them with different actors. In practice, different activities socialize Party members, linking them to a particular sphere. I distinguish between four types of integration. “Central integration” describes a link between Party member and Party centre. For example, the report of the 19th Party Congress emanated from the centre and the study of Xi Jinping's speeches relates the grassroots Party member to the top. Similarly, the inclusion of slogans reaffirms the centre's position. Lastly, Party classes in the Party branches are mandated by central authorities. Central integration therefore lists activities that directly embody central authority.

“Party integration” is similar. Reciting the oath and paying membership dues symbolize a link to the Party, not the centre. Likewise, visits to memorial sites, patriotic education or learning about the Anti-Japanese War all originate in the Party's “heroic” history and bring the past to life. Recreating the deeds of model cadres, listening to stories, singing revolutionary songs and performing dances personify and concretize these narratives. All of these activities share the common component that they are endowed with the mystical authority of the “Party” rather than the centre.

“Local integration” is self-explanatory. Implementing local policies and instructions, paying solicitude visits to elderly Party members who are experiencing difficulties, and forging links with local businesses are activities that relate Party members to their own locality. They are spatially confined activities and often highly specific. A Party branch's integration with “outside” non-Party organizations shares this characteristic although changes the activity's direction. For example, “propaganda work” happens locally, but its subject is the wider public rather than Party members. Here, the Party branch interacts with the community.

The categories are not perfect but represent the general direction of an activity. Thus, symbols can integrate a multitude of meanings that frequently undergo change. For example, the “Stay true to our original aspiration” (buwang chuxin 不忘初心) slogan both signals central and Party integration. Xi Jinping first used the phrase in July 2016 before it became the name of a song performed at the Chinese New Year's Gala in 2017 (“Stay true to our original aspiration, keep moving forward”). Thereafter, it entered the 19th Party Congress report in October 2017 and became the central slogan of an education campaign launched in May 2019. Focusing on rediscovering the CCP's past and its “founding mission,” activities linked to this slogan include visits to memorial sites, patriotic education and red songs, to name a few. It therefore signals a commitment to follow the political line of the centre as well as the Party's history more broadly, and has become an important theme for TPDs.

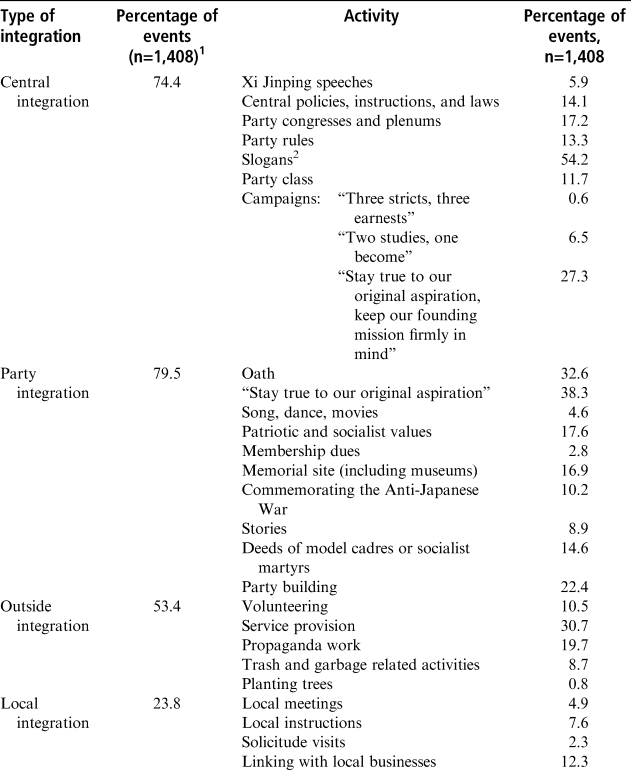

An analysis of the dataset reveals that 28 activities together form 97 per cent of the 1,408 TPDs from 2015 to 2020. These activities channel four types of integration: central, local, Party and outside. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of Integration and Activities

Source:

Author's compilation.

Notes:

1Percentages do not add up to 100 because TPDs integrate multiple activities; 2Slogans include the “Four consciousnesses,” “Four confidents,” “Two protects,” “Four follows,” “New era,” the “China dream,” “Socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era,” “Stay true to our original aspiration” and the “Great rejuvenation.”

Integration with the centre is one of the main aims of the TPDs: 74.4 per cent of all TPDs involve at least one activity that links the individual to the centre. Examples of this kind of activity include the study of a speech by Xi Jinping or a recently promulgated policy, law or Party rule, or an instruction published by the centre. For example, the amendment of the Party Constitution was widely studied, as was the Supervision Law of March 2018. Strikingly, only 5.9 per cent of TPDs include reviewing a speech by Xi Jinping. TPDs are more focused on implementing directives from the centre. For example, the reports from the Party Congresses and plenary session were widely studied, either verbatim or else in “spirit” (17.2 per cent). Similarly, many TPDs reviewed Party rules, such as the 2017 Party Constitution or the CCP's “Disciplinary punishment regulations” (13.3 per cent). This was often connected to a “Party class” (11.7 per cent), which included a lecture, usually by the head of the branch. It is notable that Party campaigns were not followed well. For example, after the centre institutionalized the “Two studies, one become” (liang xue yi zuo 两学一做) formulation (of studying Party rules and Xi Jinping's speeches and becoming a proper Party member) in 2016, TPDs were held with that aim in mind. Overall, execution was patchy, with 6.5 per cent of TPDs held from 2016 to 2020 mentioning it: 50 per cent in 2016, 27.5 per cent in 2017, a mere 4.5 per cent in 2018, and just 2.5 and 0.4 per cent in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The 2015 “Three stricts, three earnests” (san yan san shi 三严三实) education campaign fared even worse, only being referred to by 0.6 per cent of TPDs in the sample. The 2019 “Stay true to our original aspiration, keep our founding mission firmly in mind” campaign was comparatively more successful in penetrating grassroots Party branches, with over a quarter of TPDs referencing it. Concluding in January 2020, the “Decision” of the CCP's Fourth Plenum in October 2019 had already stipulated the intention to institutionalize the campaign. However, most notable is the adoption of slogans that tie the grassroots Party branch to the centre: over half of all TPDs use official slogans to showcase their loyalty. While central integration is clearly important, Party branches focus on slogans, foundational documents and broader narratives in general rather than on concrete policies and campaigns.

Apart from central integration, the TPDs are an attempt to integrate the individual with the Party in general. Over three-quarters of TPDs (79.5 per cent) involve an activity that affirms an individual's bond to the Party and 32 per cent of all events include a review of the Party's oath. The oath is therefore the most common activity of TPDs. There are two issues to note here: first, of all activities, the oath is an adequate middle ground to show allegiance. From the Party's perspective, it is a performance wherein the individual signals submission to the organization. However, from the Party branch's perspective, the oath is also the easiest activity to organize and perform. It is clearly scripted, has a fixed content and does not require much preparation. Furthermore, it yields good promotional photos. Its ubiquity therefore is as much a signal of the Party's authority as it is the simplest way for Party members to convey their acceptance of this authority, aside from incorporating official slogans. Second, while Xi Jinping and the Politburo Standing Committee publicly retook the oath after the 19th Party Congress, oath-taking at the grassroots is not a reaction to top-level practices. Rather, the data indicate that the number of TPDs has been gradually decreasing, from 52 per cent in 2015 to 17 per cent in 2020.

Another way of showing commitment to the Party is to understand its history, its origins and its mission. Hence, understanding the “founding mission” of the Party is viewed as a highly important TPD activity (38.3 per cent). One of the first events to incorporate it was held by the CCP's Youth League and bureau for civil affairs in Yanqing district.Footnote 40 Celebrating the founding of the CCP, participants gifted elderly “heroes” and “Party members” with rice, noodles, cooking oil, milk and fruit. After a theatrical performance by young pioneers, kindergarten children and volunteers, the generations mingled. Sitting together in discussion circles, the elderly donned military uniforms and recounted stories from the Anti-Japanese War and “revisited the red memory,” contrasting it with the current “happy” life. Lastly, all the participants came together to revisit the Party oath. According to the TPD summary, this reminded all young Party members to “stay true to our original aspiration,” have firm beliefs and carry out their “solemn promise to the Party.” This linked the slogan with concrete techniques at the grassroots. In particular, the involvement of veterans and the telling of war-time stories exposed the contrast between a dark past and a cheerful present. It showed where the Party came from and highlighted the path it had taken. Younger Party members who had not experienced this past were the main audience. While this setup acknowledges that the elderly and young members are different, their unity was symbolically established by swearing the oath.

Other activities elaborate this “mission.” One is storytelling. The narratives of model cadres, their lives and achievements occupy an important place in TPDs (14.6 per cent). Another such activity is a trip to a museum or memorial site for “Communist martyrs” and “heroes” (16.9 per cent). Lastly, singing revolutionary songs and dancing, in addition to historical movies, engage the individual (4.6 per cent). These three activities, while stimulating in different ways, are aimed at transmitting the Party's broader aims and values to the Party member. Likewise, the advance of the Party during the Anti-Japanese War (10.2 per cent) fosters an atmosphere of nationalism and strengthens the individual's identification with the CCP. While these are “patriotic education” activities, they are not based on the study of documents nor are they seen as such. This indicates that the fostering of patriotic feeling is not an explicit objective of the activities but a by-product. Activities associated with the broader Party-building framework are important as well (22.4 per cent) because they link a TPD to the grander aim of Party building. Other, less important activities include the paying of membership fees, which, as a ritual, is comparable to taking the Party oath. While not prominent, paying dues has become a regular part of the TPDs (2.8 per cent). Here, however, the individual's relationship with the Party is more akin to an exchange where faith in the CCP's mission is commodified. Paradoxically then, the capitalist contract signifies submission to the socialist creed. Zhihong Gao and Xiaoling Guo have observed the same phenomenon with the “red” memorial sites, which are a “practice of the capitalist ideology” to “re-incorporate the ideology of socialism.”Footnote 41 Regardless, these activities all reinforce the Party's claim to authority rather than that of a particular leadership group or level of organization. They are important for shoring up support for the CCP in the long term as they expose ordinary Party members to the CCP's narratives. At the same time, they indicate that Party branches do not shy away from conducting more complex TPDs.

Compared with central and Party integration, the grassroots Party branch's linking with the outside community (53.4 per cent) and its own locality (23.8 per cent) is de-emphasized. Roughly one-third of all TPDs include references to service provision. While this might be dismissed as merely parroting the Communist creed, TPDs put this into practice through volunteering. While in 2015 only 3 per cent of TPDs engaged in voluntary activities, by 2020, this has reached 17.5 per cent. Here, the Party's traditional role in connecting with the masses is reconceptualized as volunteering, for example by cleaning up the streets (8.7 per cent) or planting trees (0.8 per cent). During the coronavirus pandemic, for example, one Party branch assisted with resident registration and taking temperatures.Footnote 42 Likewise, for propaganda work, a Party branch might distribute leaflets to citizens to raise awareness of policies or laws, as in the introductory case study. Regarding local integration, the most prominent activity in 2019 and 2020 was integration with enterprises. Party groups have become much more active in aligning themselves with the Party, jumping from a mere 8 per cent in 2018 to 13 per cent in 2019 and 21 per cent in 2020. In one example, the Badaling 八达岭 Tourism Company organized a TPD to show “loyalty to the Party, walk closely with the Party, [and] become a good Party member for the new era” that included reading the Party Constitution, taking the Party's oath and singing red songs, among other activities.Footnote 43 Compared to integration with enterprises, the study of local Party meetings or instructions and solicitude visits to elderly Party members are less emphasized.

The predominant aim of TPDs therefore is to integrate the individual with the centre and the Party organization. Of the 1,408 events in the sample, 1,271 (90.2 per cent) conducted at least one activity linked to the centre or the general Party. Concrete policies and leadership speeches are neglected in favour of key documents, broad history lessons and mechanistic oath-taking.

Building the Party and Centre's Broader Authority

Instead of reacting to events at the centre, Party branches focus on certain activities to foster a general atmosphere supportive of the Party. Ritualization of organizational life in Party branches – the Party's nerve tips – is critical to ensure the longevity of the Party as an entity. After all, not all Party members are leading cadres or involved in policy implementation. Rather, they have different occupations and joined the Party for different reasons. From the centre's perspective, it is more important that members are exposed to organizational principles and major decisions rather than specialized and context-specific instructions, speeches or even campaigns. Integration implies organization and exposure to ideology. Thus, activities such as a museum visit are more important than the study of leadership speeches or the execution of a campaign. Similarly, group-building exercises that engage with the Party's values in a more informal atmosphere are often more effective. Exposure raises awareness, and participation in activities, even if it is apathetic, signifies engagement. Accordingly, the holding of a TPD and its ritualization as a monthly event is important; the standardization of activities is of secondary significance. Quantity becomes more important than quality.

This interpretation gains support from the shift towards more abstract and interactive forms of study to engage broader swathes of Party members. If quantity and ritualization are more important, shallow exposure to the Party is preferable to the deep study of complex documents. Hence, the Party's historical legacy and values, the Party oath and slogans as an acceptable middle ground for both the grassroots and the Party centre become more important relative to other activities. A yearly breakdown of events confirms this view.

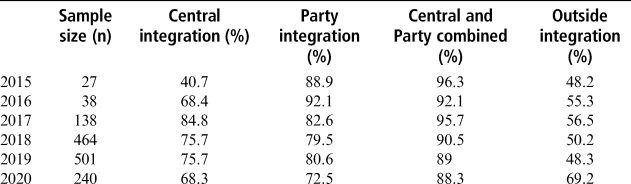

Table 2: Central and Party Integration and Average Number of Activities

Source:

Author's compilation.

Integration with the centre and the Party in general has always been a top priority for TPDs. Events that contained an activity aimed at integrating the individual with the centre more than doubled from 2015 until 2017, before falling off to 68.3 per cent by 2020. This fall is mirrored in the decrease of “Party integration” (from 82.6 to 72.5 per cent). The combined percentage of TPDs that included an activity that integrated Party members with either the centre or the Party was very high throughout the observed period. In 2015, 96.3 per cent of cases involved either type; this number remained relatively stable until 2017, after which it dropped to 88.3 per cent in 2020. While this signals a stronger focus on the Party and associated activities than on the centre, the most recent drop in 2020 is associated with a higher degree of outside integration, particularly volunteering and propaganda. This shows that while maintaining a high level of coherence with the centre and the Party's values, local Party branches have become much more confident and assertive in their relationship with the people. It remains to be seen whether this is a temporary spike in response to the coronavirus pandemic or represents a structural change.

Central and Party integration demonstrates the growing importance of casting a wider net with which to engage Party members, focusing less on specifics and more on general acceptance and knowledge of the Party's aims, values and intentions. Furthermore, it shows how difficult it is for the centre to extend its reach into its own Party branches. While it can mandate Party branches to hold TPDs, it does not have the capacity to determine their conduct and prescribe their content. However, at the same time, Party branches appear confident enough to increase their local profile, fan out and engage the people.

Fragmentation and a Stronger Party

TPDs have become a potent way to operationalize ideology and exert control over the grassroots. By tying the individual Party member to the Party and its centre, do TPDs lead to a more integrated Party? In short, no. Rather paradoxically, TPDs lead to greater fragmentation. Again, rather paradoxically, this might strengthen the Party.

There are two indicators of fragmentation. First, TPDs are a space used by the Party centre to socialize Party members. However, they are also arenas in which Party members define their relationship with the Party. Neglect, manipulation or omission are therefore indicators of how participants express their relationship. For example, while a third of TPDs include the Party oath, the majority do not. Likewise, only one-fifth of TPDs reference Party building. This suggests that four-fifths of Party branches do not link TPDs to the ongoing thrust to strengthen the Party. Only 16.9 per cent visited a memorial site or museum; 83.1 per cent did not. That no single value exceeds 38.3 per cent points to fragmentation.

Another form of fragmentation results from the growing divorce between form and content. The explosion in the number of TPDs was accompanied by a decrease in the average number of activities organized for TPDs. In 2015, TPDs conducted 5.9 activities on average. This number rose to 7.3 in 2017. However, by 2020, it had dropped to 5.8. In other words, on average, each of the 240 events in 2020 involved fewer than six activities. These are all indicators that Party branches have embraced the ritual of the TPD but not necessarily its content. The focus is not on diversity but rather the formal exercise of putting on a TPD. TPDs therefore risk becoming tick-box affairs where local Party branches go through the motions rather than substantially engage with their members. In the worst case, excessive formalism can destroy Party members’ initiative in devising TPDs and therefore the Party's organizational life, with TPDs reduced to theatrical performances.

Manipulation at branch level and a divorce between the form and content of TPDs indicate a high degree of diversity regarding their implementation. Consequently, ideological exposure at the grassroots is decidedly uneven. Party members from one branch will be involved in different activities to members from neighbouring branches. This is particularly problematic because the TPDs are different from regular study sessions. Whereas study can happen on an ad-hoc basis, TPDs are planned and complex affairs that present ideological values as statements in texts and in physical form, for example in visits to memorials. It is telling that taking the Party oath is the most widely adopted activity: it is easy to perform and heavily scripted. In contrast, outings are much more time consuming and require organizational effort and capital. This leads to a fragmented Party at the grassroots, where exposure to ideology and the Party's values depends on the Party branch and its leaders.

Such fragmentation indicates that while TPDs are tentatively effective at establishing a bond between the individual and the Party and its centre, the actual process has many variations. Paradoxically then, while TPDs are meant to homogenize the grassroots, the uneven organization of activities and exposure to ideology instead leads to further fragmentation.

Greater fragmentation might weaken the Party, but it is equally likely to strengthen it. While growing diversity in TPDs conduct is not ideal, it is tolerable. Kertzer notes that “ritual can promote social solidarity without implying that people share the same values, or even the same interpretation of the ritual.”Footnote 44 This suggests that the key to building solidarity and a common identity among Party members lies in “action” rather than “thinking.” Bakken contends that morality in China is a “social form” and based on “how you adapt to outward rules.”Footnote 45 Belief in ideological precepts is not that important. Rather, the focus is on behaving in a certain and prescribed way. This indicates two issues. First, the growing number of TPDs and their proliferation at the grassroots is sufficient to foster a sense of integration. Individual participation in events is more important than actual content. Second, action must be collective. Indeed, by integrating a variety of events, TPDs are geared towards supporting collective action within the Party branch framework. As such, the integrated rituals of the TPD are more likely than other forms of organizational life to reproduce the Party's values.

Even the passive exposure to ideological slogans familiarizes participants with the Party. The loss of a diverse set of activities within TPDs is not an issue. Shaping TPDs through manipulation, neglect or omission is not a problem as long as the bottom line is protected. According to Lane, what matters are the “immutable parameters” laid down by an ideology, on which basis diversity is allowed.Footnote 46 Accordingly, TPDs relate to the Party's ideological outlook. The very act of conducting them links the Party branch to the Party. This is regardless of what TPDs actually encompass. This echoes Joseph Schull, who regards the existence of a variety of ideological beliefs in Soviet-type systems as “normal.”Footnote 47 He argues that appropriation and the introduction or repression of ideological terms shows the centrality of ideology. Here, tying actions to ideological precepts makes them “legitimate.” Hence, even when Party branches conduct seemingly unrelated activities, they nonetheless engage with the ideology of the Party and reproduce it: the very conduct of TPDs indicates the success of ideological control.

Conclusion

How can the Party guarantee some degree of conformity among its regular members amid a rapidly changing and increasingly diverse environment? In 1983, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 warned that when focusing on economic construction, the Party must not neglect ideological work.Footnote 48 Hence, in 1994, focusing on Party building and “improving the content of activities and work method” of grassroots Party organizations became top priorities.Footnote 49 Even in the 21st century, the problem persists: Thornton describes how some Party branches in Shanghai organized pillow fights, “Da Vinci Code” trivia quizzes and speed-dating events.Footnote 50 At the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Xi Jinping criticized such behaviour as a sign of the “weakness, voidness, and marginalization” of organizational Party life and called for “promoting innovation of the Party's grassroots level organization and activities.” The emergence of TPDs is a response to this.

This article illuminates how the Party attempts to operationalize ideology in an effort to exert control over its own grassroots organizations and boost its authority in the eyes of its regular members.Footnote 51 Situated at the nexus of the Party centre and ordinary Party member, TPDs are an arrangement of the Party's organizational life that extends the Party's values to the grassroots. It is another technique to control regular Party members, alongside the regular nomenklatura and disciplinary system. As shown, TPDs are akin to rituals: standardized, integrated and, most importantly, the purveyors of ideological values. TPDs integrate the grassroots with the Party in general as well as its centre. The ritualization of TPDs demonstrates how Party members are slowly socialized into adhering to the Party's authority. In a period of growing social diversity, TPDs also illustrate the Party's attempts to narrow the space for different views, create further internal cohesion and to diversify its sources of legitimacy.

It would be an oversimplification to depict the Party as succeeding in engulfing the individual Party member in a maelstrom of ideology and organization. The TPDs are far from standardized and their execution is highly fragmented. However, the tolerated diversity is conditional on an outward acceptance of the Party's ideology. Thus, it should not be regarded as harmful to the Party's position. The explosion of TPDs and their coupling of physical activities and textual statements positions them as an effective way to organize and educate the grassroots. Passive exposure to the Party's narratives, slogans and documents is sufficient to bind the grassroots members to the centre and makes them more susceptible to rapid mobilization in crisis situations. This was particularly evident in 2020, when integration with the people increased dramatically during the coronavirus pandemic. Then, Party branches and their members were mobilized as volunteers to combat the virus and provide services. Hence, since Thornton's study, the pendulum has swung back towards the Party.Footnote 52 Accordingly, the operationalization of ideology must receive more attention as an everyday technique for socialization that fosters a sense of inevitability wherein individuals are unable to conceive of alternative political arrangements. More broadly, institutional pressures also lead to organizational changes. Here, future research can consider how external changes result in a redefinition and restructuring of the CCP's organization.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his thanks to Patricia Thornton and Andrea Ghiselli for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Jean Christopher MITTELSTAEDT is a departmental lecturer in modern Chinese studies at the University of Oxford.