As Patricia Thornton points out in her “Introduction” to this issue, authoritarian regimes do not usually live long. Different types of authoritarian regimes, on average, have different life expectancies, with Leninist regimes surviving the longest. The Soviet Union lasted for 70 years, and North Korea is, alas, still going after 75 years. As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrates its 100th anniversary (72 years in power), explaining its longevity has become a cottage industry in the field of China studies.Footnote 1

In recent years, the primary answer to this conundrum has been “institutionalization.” Andrew J. Nathan advanced this explanation in his highly influential 2003 article, coining the now widely used expression, “authoritarian resilience.”Footnote 2 For Nathan, the succession of Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 to the general secretary position was an extraordinary expression of the organizational evolution of the CCP, from a party based on factionalism to one largely institutionalized. As Nathan put it, “Never before in PRC history has there been a succession whose arrangements were fixed this far in advance, remained so stable to the end, and whose results so unambiguously transferred power from one generation of leaders to another.”Footnote 3 Nathan attributes this peaceful transfer of power to four factors: succession has become increasingly norm-bound; the importance of factionalism has diminished as the emphasis on meritocracy has increased; functional specialization has increased; and the institutions that allow for political participation have expanded, thereby increasing the legitimacy of the regime.Footnote 4

Many scholars agree with Nathan. Cheng Li argues that China has developed a degree of “intra-party democracy” that has allowed the leadership to practise “collective leadership.” Although Li focuses on competing coalitions (or factions), he contends that the different skills of different coalitions allow them to compromise. Behind this new collegiality lies institutionalization.Footnote 5

Similarly, Alice Miller writes, “Since the beginning of the Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 era, elite politics in China [have] undergone deliberate, incremental institutionalization. As institutionalized processes of leadership decisionmaking have taken hold, the dynamics of leadership competition have been changing, in favor of an increasingly consensus-building collective leadership.”Footnote 6

This emphasis on institutionalization led the political scientist Milan Svolik to write of Xi Jinping 习近平, when he was still heir apparent, that “He will be expected to serve no more than two five-year terms and be accountable to a set of institutions within the Communist Party of China that carefully balance two major political coalitions as well as regional and organizational interests within the Chinese political system.”Footnote 7 However, as is clear now, Xi Jinping has overthrown many of the norms and practices that have guided the CCP in the reform era, destroyed the factional system that Cheng Li describes, constructed a political system revolving largely around himself, and seems headed for a third term in office when the 20th Party Congress meets in 2022. Svolik's felicitous prediction has clearly been upset by the realities of Chinese politics.

Svolik is not the first person to be misled by the vagaries of the Chinese political system (and by students of China), but the failure of his prediction raises the second question that hangs over the field: how do we explain the concentration of power in the hands of Xi Jinping? Communist Party members are now expected, among other things, to support the “two upholds,” one of which is “to uphold Xi Jinping as the core of the Party centre and core of the entire Party” (the other is to “uphold the Party's authority and unified leadership”). This degree of personalization of Chinese politics has not been seen since the days of Mao Zedong 毛泽东.

One simply cannot explain Xi Jinping's emergence as a personalistic “core” of the Party and maintain that elite politics are “institutionalized” or that the Party practises “collective leadership.” Obviously, something went wrong in our analyses at some point. It is time to “walk back the cat” and try to discern where the analysis went awry.Footnote 8

A starting point is to grasp what is meant by “institutionalization.” This is a term used by different people to mean different things. It can refer to both formal and informal processes. It can refer to the management of state or party employees (cadres, in China's case), including the recruitment, promotion and retirement of personnel. Sometimes, it refers to what are better called “norms,” which means something akin to “how things have always been done.” Norms are more easily bent or broken than institutions. Institutionalization is also a process, not something that is achieved in one go. Because we are looking at elite politics, however, the central meaning of “institutionalization” is that there are widely accepted rules that are not easily changed and that define how leaders are chosen and promoted. In particular, it refers to the peaceful transfer of power from one generation of leadership to another. It means that new leaders are chosen not because they have the support of a stronger faction or because they have won out in power struggles in which losers face dire consequences, sometimes even including death. There needs to be a widely understood process.

In the past four decades, there have been changes in Party procedures which have established important norms that have acted as checks and balances in the Party and have led to the perception of institutionalization. These measures include the regular convening of Party congresses. Since 1977, Party congresses have been held every five years, regardless of the tensions within the Party – including those which led to the events at Tiananmen Square in 1989. An important exception was the convening of the Party Representative Meeting in 1985, which was, for all intents and purposes, a Party congress inserted between the 12th and 13th Party Congresses. This mechanism, which followed no known institutional rules, allowed Deng Xiaoping to significantly rejuvenate the Central Committee and thus ward off the threat of a re-emergence of Cultural Revolution activists.

In addition, retirement rules have generally been accepted. Central Committee members must retire at 65 (with a few exceptions), and no one is appointed to the Central Committee above the age of 63. Retirement rules were extended to the Politburo in 1997, when the age was set at 70, and revised downward (to 68) in 2002. It appeared that retiring Politburo Standing Committee members were to be replaced by age-eligible members of the broader Politburo, but that rule was thrown into question by the 19th Party Congress in 2017 (see below).

The “helicopter” promotions (promoting people two or more steps at one time) that were common in the Cultural Revolution have largely been replaced by step-by-step promotions. Again, this rule has been thrown into question in recent years.

One result of this “normalization” of politics is that a new general secretary is surrounded, both on the Politburo Standing Committee and in the larger Politburo, by people who may or may not be “allies.” Normally (to the extent that we can generalize over only four cases), the general secretary is able to promote allies in his second term and thus become stronger.

This précis of political procedures, however, leaves out important characteristics of institutionalization. China lacks the “third-party enforcement” typical of institutionalized political systems and which prevents what happens so often in authoritarian regimes, namely that “institutions do exactly what their creators want them to, and leaders adjust institutional forms when doing so is in their interest.”Footnote 9 In other words, there can be what might be called “false institutionalization” – the emergence of “rules” that do not constrain leaders but rather get pushed aside when they are not convenient. This is the case with China.

When thinking about the Chinese political process, it is useful to try a mind experiment. Imagine, if you will, that you are dropped into the general secretary's chair following a Party congress. You look around the room and see a number of faces (usually 25), some friendly, others not so friendly. What do you need to do to secure your position and, perhaps, to get something done?

You quickly discover that some positions are more important than others, and you try to appoint allies to these positions. Although there is no list of such critical positions, from the practice of Chinese politics, we can intuit that several positions are more crucial than others. Apart from the membership of the Politburo Standing Committee, critical positions include the heads of the General Office, the Organization Department, the Propaganda Department, the Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the ministries of State Security and Public Security, and the Secretariat. Control of the military through the Central Military Commission (CMC) is also essential. Controlling such positions leads to relative political centralization; failure to have allies in such positions leads to weakness and, perhaps, the loss of power.

The complete centralization of power, however, is difficult and perhaps not desirable. There are multiple groups in the CCP; trying to exclude all those who are not clear allies is likely to provoke debilitating struggles within the Party. Moreover, there are often important people that one does not necessarily want in critical positions but who are too important to exclude. Or one might want to grant senior leaders important, even critical, positions in an effort to build a coalition. In other words, there is often an informal mechanism to balance power. Such efforts at achieving political balance do not manifest the hierarchical principles of textbook Leninism, but they do reflect the informal distribution of power in the Party.

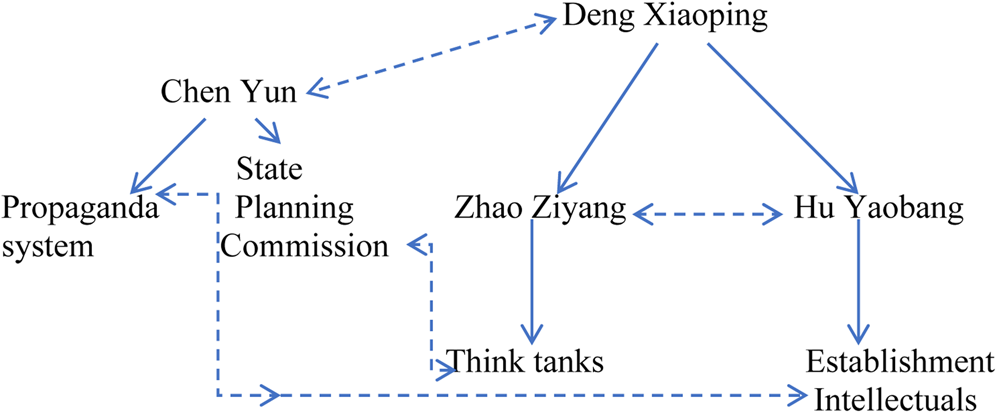

The classic case of such balance was in the Deng era before Tiananmen. Deng relied on Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 and Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 to push his reform agenda, but the Party and state machinery was largely in the hands of conservatives – veteran cadres who made up the mainstream of the Party. In many cases, these were people who had suffered during the Cultural Revolution and who needed to be rewarded by being brought back into the governing coalition. The premiere conservative was Chen Yun 陈云. Chen's relationship with Deng was complicated. There is no doubt that Chen supported Deng's return to power; he and veteran military leader Ye Jianying 叶剑英 had called for Deng's rehabilitation at a Party work conference in March 1977.Footnote 10 Historically, Chen had held higher positions in the Party than Deng and at an earlier date. Chen Yun first joined the Provisional Politburo in 1931. He continued to serve on the Politburo that was elected at the Fifth Plenary Session of the Sixth Central Committee in January 1934. Deng Xiaoping did not enter the Politburo until 1945. So, there is no question that Chen Yun was Deng's senior in a party that valued seniority (with the obvious exception of those who were purged). However, Chen Yun did not have the military and foreign affairs experience that Deng had, so as reform unfolded, Deng took on the role of “paramount” leader while Chen joined the Politburo Standing Committee and headed the Central Discipline Inspection Commission (CDIC). As China's senior-most economic policy specialist, Chen also became head of the State Financial and Economic Commission until that was replaced in 1980 by the Party's Financial and Economic Leadership Small Group, headed by Zhao Ziyang. But, as Zhao Ziyang recalled, even as premier and head of the Financial and Economic Leadership Small Group, he had no ability to appoint the head of the most important economic organ at the time, the State Planning Commission.Footnote 11 It was that separation between the premier and the State Planning Commission that reflected the informal balance of power between Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun.

The same phenomenon occurred in the ideological sphere. Coming out of the Cultural Revolution and setting out on an uncertain reform direction, ideological issues were bound to be at least as contentious as economic issues. It was clear that China needed to move away from Maoist doctrine – as the discussion on “practice as the sole criterion of truth” showed – but it was not clear how far and how quickly ideology could change. A conference on theory, convened between January and March 1979, revealed tensions right at the beginning of reform. Speakers at the conference were largely drawn from Hu Yaobang's network of “establishment intellectuals.” Such intellectuals may have been “establishment,” but they were not orthodox. Wang Ruoshui 王若水, deputy-chief editor of People's Daily, criticized Mao Zedong harshly and was strongly rebuked, albeit not by name, by Deng Xiaoping. The conference closed with Deng Xiaoping giving his famous speech, “Uphold the Four Cardinal Principles,” which was aimed at reining in some of the excesses he believed the conference had voiced. Although there were many ideological battles in the early 1980s – particularly the controversy over Bai Hua's 白桦 movie script, “Unrequited love,” in 1981 and the campaign against spiritual pollution in 1983, a critical moment was reached in 1984 when the Fourth Congress of Writers and Artists convened to elect a new leadership. Normally, the Organization Department would take charge and determine who would win the “elections.” On this occasion, however, Hu Yaobang told the Organization Department not to intervene. The result was that many of the old guard lost their positions only to be replaced by younger people, like Liu Binyan 刘宾雁, who were still smouldering over the campaign against spiritual pollution.Footnote 12

These ideological conflicts, like those in the economic arena, reflected the balances that had been established. The general secretary of the Party (then Hu Yaobang) is supposed to be in overall charge of the Party, including ideology. But Hu Qiaomu 胡乔木, Mao's former secretary, was a member of the Politburo and held great prestige owing to his long-time association with the chairman. Furthermore, Hu Qiaomu's protégé, Deng Liqun 邓力群, headed the Propaganda Department. So, just as Zhao Ziyang could not control the State Planning Commission, Hu Yaobang could not control the Propaganda Department.

These cleavages created an important system of balances, as depicted in Figure 1.Footnote 13 On the one hand, such a system of balances allowed the Dengist system to be something of a “big tent,” consisting of more reform-minded leaders on the one hand and more orthodox leaders on the other. Deng was in the middle, balancing these complex and competing forces. However, these balances tended to polarize differences as economic and ideological differences widened over the course of the 1980s. Balances are not institutions; they shift as issues change and as people fall from power or die. In the end, the tensions embodied in the Dengist system of balances were a part of the stresses that led to the events around Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Figure 1: Balances in the 1980s

Notes: Solid lines indicate a relationship of subordination; dashed lines indicate tension.

The collapse of these balances in the late 1980s did not mean the end of balances. When Jiang Zemin 江泽民 was suddenly plucked from Shanghai to replace Zhao Ziyang as general secretary, he faced an uphill battle. Being general secretary was not enough. He had the support of Chen Yun and Li Xiannian 李先念 and the acceptance of Deng Xiaoping, but Li Peng 李鹏 was not welcoming, reportedly denying Jiang office space at first. Qiao Shi 乔石 was in many ways the most qualified to replace Zhao. Qiao had headed the General Office in 1983, then the Organization Department in 1984, joined the Politburo in 1985, and the Politburo Standing Committee in 1987. But because he had opposed the use of force in 1989, he was passed over. He could not have been welcoming to Jiang.Footnote 14

As complicated as the politics at the top were, the most serious issue Jiang faced was the hostility of Yang Shangkun 杨尚昆 and his brother Yang Baibing 杨白冰. Yang Shangkun was former vice-chair of the CMC, a position he ceded to his brother when he became president of the People's Republic. As long-term leaders of the PLA, they had built considerable support in that institution, which effectively froze out Jiang Zemin. It was not until after Deng purged the Yang brothers following the 14th Party Congress in 1992 that Jiang would be able to begin building support in the PLA.

Still, Jiang would not become “core,” as Deng had called him, until after the death of senior leaders Chen Yun and Li Xiannian and after Deng Xiaoping's health declined. It was only with the fourth plenum in 1994 that “power was passed on to the Third Generation of Leadership,” as a People's Daily editorial put it.Footnote 15 Jiang did not inherit an institutionalized position; he fought to centralize power and was supported by Deng Xiaoping.

The idea that Chinese politics, particularly the succession issue, have become institutionalized relies heavily on the succession of Hu Jintao. As Andrew Nathan correctly points out, this was the most orderly, peaceful and deliberate succession in the history of modern China, excepting the Republic of China on Taiwan. It was, nevertheless, a rather strange succession because it was not rule bound but rather decreed by Deng Xiaoping. When Deng Xiaoping was exiled to Nanchang 南昌 during the Cultural Revolution, he had a great deal of time to think about what had gone wrong. How could a successful revolution, led by Deng's political mentor Mao Zedong, have gone so far off track? Deng articulated some of his thoughts on this subject in his justly famous speech on “The reform of the Party and state leadership system.” Perhaps his central thought in that talk was that power had become overly concentrated, leading to mistakes. When he spoke to the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, he elaborated, saying that it was “feudal” for one leader to designate his successor.Footnote 16 No doubt this comment was directed first and foremost at Hua Guofeng 华国锋, who was about to be demoted, but it seems that Deng held fast to this thought. It is natural for a leader to want to remain in power or to designate his own successor, but Deng had, along with Chen Yun, pushed for term limits in order to promote orderly succession and curtail “feudalism.” In 1992, Hu Jintao was placed in charge of the group that vetted those who would be promoted to the Central Committee and leading Party bodies at the 14th Party Congress. Hu was then named the youngest member of the Politburo Standing Committee at 49 years of age. When Qiao Shi was forced to step down in 1997 as Jiang Zemin instituted a retirement age for Politburo members, he revealed to high-level Party members that Deng had designated Hu as Jiang's successor, and that the decision had been approved by the Politburo Standing Committee. Making that knowledge “public” effectively prevented Jiang from somehow wriggling out of that decision.Footnote 17 However much Jiang may have wanted to designate his trusted aide Zeng Qinghong 曾庆洪 as his successor, Jiang had to yield his position to Hu Jintao.

But that did not mean he could not take a number of steps to constrain the new general secretary. On 22 October, Xinhua announced that Huang Ju 黄菊, the Party secretary of Shanghai, and Jia Qinglin 贾庆林, the Party secretary of Beijing, would be “transferred to the centre.” The late date of this announcement suggested strongly that the process that had generated this decision was not part of the regular transfer of power but rather the assertion of strong political pressure. As we soon learned, the positions they would take up “at the centre” were seats on the Politburo Standing Committee, as that body was expanded from the usual seven to nine members, the largest it has been in the reform era. Because both Huang and Jia were Party secretaries of special municipalities that have seats on the Politburo, their successors, Liu Qi 刘淇 in Beijing and Chen Liangyu 陈良宇 in Shanghai, were promoted to the Politburo. Thus, in one swipe, Jiang managed to put two more of his protégés on the Standing Committee and add two other followers to the Politburo.Footnote 18

Jiang then decided to emulate Deng Xiaoping and retain his position as head of the CMC. At that time, Jiang's effort to cultivate support in the PLA allowed him to promote Xu Caihou 徐才厚 and Guo Boxiong 郭伯雄 as vice-chairs of the CMC. Throughout Hu Jintao's ten years as general secretary, he would never be able to appoint his own followers as vice-chairs of the CMC.

These moves to pack the Politburo Standing Committee and control the leadership of the CMC suggest that Jiang Zemin was at least as strong, perhaps even stronger, after he gave up his position as general secretary as he was when in office. Hu Jintao had not succeeded to a formal position so much as to a set of informal arrangements, many of which were out of his control. Reportedly, the Politburo approved a resolution that Jiang should have a critical role to play with regard to personnel.Footnote 19 PRC media never referred to Hu as the core. There was a reason for that: Jiang remained the core. Jiang had centralized power with the help of Deng Xiaoping; Hu Jintao was never able to centralize power, in part because Jiang prevented him from doing so.

Breaking the Balance

Jiang continuing as the core created a situation in which neither Jiang nor Hu could rule effectively. Jiang influenced major personnel appointments, but Hu could set a new tone by talking about “scientific” socialism and by adding a humanist/Confucian element by “taking people as the basis” and talking about building a “harmonious society.” Hu certainly made progress in expanding welfare, especially healthcare, and asserted himself, with the strong support of Wen Jiabao and others, to arrest Bo Xilai 薄熙来.Footnote 20 However, Hu made little progress addressing what many took to be the pressing needs of the time – constitutionalism, law, environmental protection, income equality, and so forth. By the end of the Hu Jintao period, a sense of stagnation was palpable. As the Central Party School's deputy editor of Study Times, Deng Yuwen 邓聿文, put it, “considered from the perspective of Chinese modernization, the decade of Hu and Wen has seen no progress, or perhaps even a loss of ground.”Footnote 21

The stagnation that Deng Yuwen witnessed was not only the result of Jiang Zemin's curtailment of Hu's ability to act but also because of the natural pathologies of China's Leninist system. Instead of institutionalizing, relations within the Party were increasingly personalized and monetarized (corrupt). The growth of personal networks at the provincial and sub-provincial levels reflected Party dysfunction and limited Beijing's control. Party analyses of “colour revolutions” in Ukraine and elsewhere reflected renewed fears of civil society and “peaceful evolution.”

The Bo Xilai case exposed the deep rifts in the CCP caused by this dysfunction. Bo's efforts to “put on a rival show” in Chongqing by attacking organized crime and singing “red” songs were nothing less than a challenge to the decision of the 17th Party Congress to pass him over in favour of Xi Jinping. Every member of the Communist Party knows that one should submit to decisions of the Party, but Bo, raised in one of the reddest households in China, was defying Party discipline to promote himself. Soon, Ling Jihua 令计划, the head of the Party's General Office and Hu Jintao's chief consigliere, was moved to a less sensitive position as head of the United Front Work Department. Heads of the General Office are routinely promoted to the Politburo, but this norm was interrupted by the death of his son, Ling Gu 令谷, who crashed his Ferrari, which was given to him by one of his father's associates in Shanxi, into a pillar along the Fourth Ring Road in Beijing. Ling Gu was killed, as was one of the two scantily clad young women he was driving with. The other was badly injured. The death of Ling Gu seems to have been taken as excuse to expose his father, who was guilty of organizing an “election” to promote the candidacy of himself and others prior to the 18th Party Congress.Footnote 22 Apparently, he was also guilty of massive corruption.

These signs of deep corruption and dysfunction within the Party were not reflected in the outcome of the 18th Party Congress, perhaps because they occurred too close to the opening of the congress. Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang 李克强 were anointed general secretary and premier, respectively, as expected, but the rest of the Politburo Standing Committee seats were not filled by promoting all age-eligible members of the Politburo. If the promotion of all such age-eligible members of the Politburo was the explanation for expanding the size of the Standing Committee in 2002, it cannot be the explanation for reducing the size of it in 2012. As many noted at the time, reducing the number of seats on the Standing Committee, from nine back to the more standard seven, left Hu Jintao protégés Wang Yang 汪洋 and Li Yuanchao 李源潮 off the Party's highest body. Liu Yandong 刘延东, who was also eligible according to her age, was also left off the Standing Committee – a result more attributable to the stubborn sexism of the Chinese political system (no woman has ever been promoted to the Politburo Standing Committee) than to factional politics.

Whereas the normal pattern of elite politics, to the extent that one can speak of a normal pattern over only two successors to Deng, was for the retiring general secretary to retain some influence by promoting one or more associates to the Politburo Standing Committee. However, apart from Li Keqiang, there were no Hu Jintao acolytes among the new line up, and only two (Guo Jinlong 郭金龙 and Hu Chunhua 胡春华) out of the remaining 17 on the Politburo.

What was striking about the outcome of the 18th Party Congress was the number of people who had come up through the Jiang Zemin network. Among the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, at least three can be identified as products of Jiang's network (Zhang Dejiang 张德江, Liu Yunshan 刘云山 and Zhang Gaoli 张高丽). Notably, Jiang was still exercising influence ten years after retiring. This suggests that Jiang and others hoped to cultivate Xi over a period of time before allowing him to exercise power on his own.

But the political stagnation of the later Hu Jintao era, and apparent in the arrangements of the 18th Party Congress, was soon broken by Xi Jinping's attack on corruption. The first “tiger” (high-ranked cadre) to fall was Li Chuncheng 李春城, a deputy Party secretary in Sichuan. Li was detained on 6 December 2012, less than a month after the closing of the 18th Party Congress (held 8–14 November), suggesting that the decision to detain him might have been made even before the congress opened. Detaining Li could not have been a simple decision because he had been a close associate of Zhou Yongkang 周永康 during Zhou's tenure as Party secretary of Sichuan (1999–2002). It follows that the decision to target Li must have involved a decision to charge Zhou. Prosecuting Zhou, however, was necessarily a complicated and politically fraught decision. One norm that had developed in the reform years was that members of the Politburo Standing Committee were exempt from punishment (xing bu shang chang 刑不上常). Charging Zhou with corruption, as subsequently happened, could not have taken place without extensive discussion among the top leadership and retirees, including Zhou's patron, Jiang Zemin.

It is clear, therefore, that Xi came to power with a mandate to clean up corruption. But whatever mandate Xi was given, he clearly went beyond corruption to try to eradicate the dysfunction in the Party, as outlined above. In the process, Xi centralized and personalized political rule beyond anything seen since Deng Xiaoping. Reflecting the deep cleavages within the Party, Xi charged his political opponents with conspiracy, corruption and ambition. This was no ordinary succession. As he put it:

In recent years [we] have investigated cases of some high-level cadres who have seriously violated discipline and law, especially those of Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Xu Caihou, Ling Jihua and Su Rong 苏荣, who have broken the Party's political discipline and political regulations. These must be viewed seriously. These people, the greater their power and the higher their position, the more they don't think of the Party's political discipline and political regulations as anything at all. Their actions are unscrupulous and audacious in the extreme. In some of them, their political ambition swells, and for their own interest or for the interest of a small group. They turn their backs on the Party organization and engage in political conspiracy; they collaborate with each other to wreck and divide the Party. Some leading cadres put themselves above the Party, they think of themselves as number one, and they take wherever the Party sends them as their own independent kingdom. In using cadres and making decisions, they don't report to the centre as they should, and they engage in small mountain-top-ism, small factions, small groups.Footnote 23

The deep dysfunction in the Party, as seen in the combination of corruption, deep splits within the Party and general political stagnation, brought about another danger, at least in the eyes of Xi Jinping – the possibility of “peaceful evolution.”

Xi's New Order

Xi's campaign against corruption came wrapped in a vigorous campaign against peaceful evolution as exemplified by the collapse of the former Soviet Union. When Xi went to Guangzhou in December 2012 – his first trip outside Beijing after being named Party chief – he railed against peaceful evolution, saying that the reason the Communist Party in the Soviet Union had lost power was because it had lost its ideals and confidence.Footnote 24 Xi may well have feared peaceful evolution, but the collapse of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was also a frightening lesson that could be used to justify the harsh measures he was taking to tighten control over the Party. For not the first time in Party history, the immobilisme of the Hu Jintao years would lead to decisive action.

Zhou Yongkang's arrest in July 2014 was preceded a month previous by the detention of Xu Caihou, vice-chair of the CMC. Xu's arrest was quickly followed by that of the other vice-chair of the CMC, Guo Boxiong. Much has been made of the fact that Zhou was a retired member of the Politburo Standing Committee, but it should be noted that vice-chairs of the CMC are treated as the equivalent of Standing Committee members. So, not only did Xi break the norm that gives protection to members of the Politburo Standing Committee with his arrest of Zhou, he extended that norm-breaking with the arrest of Xu and Guo. All three detentions would certainly have needed the approval of the Politburo Standing Committee members, both active and retired. Since Xu's appointment as head of the General Political Department in 2012, he had approved the promotion of 83 officers to the rank of full general.Footnote 25 Although there were operational reasons for the restructuring of the military in 2015, breaking up this network of high-ranking officers must have been high on Xi's agenda. The following year saw an attack on the Communist Youth League (CYL) for being “bureaucratic, administrative, nepotistic and hedonistic,” a critique the organization accepted.Footnote 26 So Xi's succession to power was far more than a regular transfer of office; it was more akin to a coup d’état.

Xi's concentration and personalization of power continued in the run-up to and during the 19th Party Congress, which was convened in November 2017. Before the congress even met, 17 full members of the 18th Central Committee had been caught up in the anti-corruption campaign and removed. That number far exceeds the previous record, set in 2007, when four people were cashiered for corruption. Moreover, instead of the limited intra-party democracy that had been adopted at the 17th and 18th Party Congresses, the Party reverted to its previous practice of personal recommendation. Xi Jinping interviewed 57 current and retired leaders while other leaders solicited the views of 258 other leading cadres. In addition, leaders of the CMC spoke with 32 senior military leaders about representation on the Politburo.Footnote 27 Given this tightly controlled process, it is not surprising that many associates of Xi Jinping rose to power. Xi's old friend Li Zhanshu 栗战书 gained a seat on the Standing Committee, as did his close associate Zhao Leji 赵乐际. Of the eight people on the Politburo who are eligible by age to be promoted at the 20th Party Congress in 2022, six are close associates of Xi's.

Looking at the Central Committee gives an overview of the extraordinary changes wrought at the 19th Party Congress. Of the 205 full members of the 18th Central Committee, only 78 retained seats on the 19th Central Committee (38 per cent). Normally, about half of all members are retained. And only 32 alternate members of the Central Committee were promoted to full membership (20 per cent), a reduction from the normal number of about 40. Indeed, the scope of Xi's changes far exceeds anything seen since Deng Xiaoping remade the Central Committee in the early 1980s.

Looking at the 40 members of the PLA who served on the 18th Central Committee, 27 retired – 11 of whom retired before reaching the mandatory retirement age of 65. Such premature retirement had never happened before. Two of the seven people appointed to the CMC (Zhang Shengniu 张升民 and Li Zuocheng 李作成) had never even served on the Central Committee, normally a prerequisite to being appointed to the CMC.

Similarly, there were two people (Cai Qi 蔡奇 and Yang Xiaodu 杨晓渡) appointed to the Politburo who had not previously served on the Central Committee, either as full or alternate members. In addition, four alternate members of the Central Committee were promoted to the Politburo – the last alternate member to be promoted to the Politburo was Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 in 1994. Aside from the Standing Committee, there were still 15 seats on the Politburo that needed to be filled: ten of those went to close associates of Xi Jinping.Footnote 28

Xi may have begun his tenure as general secretary with few close associates, but within five years he had centralized power and appointed close followers to the Politburo, the CMC and the Central Committee. It is true that Wang Qishan 王岐山 stepped down in accordance with the retirement norm, but even his influence was preserved through his subsequent appointment as vice-president of the PRC (although his influence appears to have been checked in recent months). We have not seen such rapid centralization and personalization of Chinese politics since Deng Xiaoping took over in 1978 – and it could only be done by breaking down the system that Deng had tried to create.

Xi's campaign against corruption has not only purged his political enemies but also has transformed the dynamics of elite politics by ending the interference of Party elders. The balances that were once essential to building consensus and moderating a leader's decisions no longer exist. At the same time, Xi has been working to reshape the Party by tightening control over cadres, increasing the power of the discipline inspection system, combing through Party regulations to discard out-of-date regulations and rewrite important ones to emphasize his own role. The recently revised “Work regulations of the Central Committee” now requires Central Committee members to take the lead in strengthening the “four conciousnesses” and carrying out the “two upholds.” The “four consciousnesses” refer to “political consciousness,” “consciousness of the overall situation,” “consciousness of the core” and “consciousness of lining up (kanqi 看齐).” Xi is, of course, the core, and “lining up” means maintaining solidarity with him. The “two upholds” refer to upholding general secretary Xi Jinping as the core of the centre and upholding the authority and centralized unity of the leadership. In other words, the work of the whole Party must revolve around Xi Jinping. If it is possible to codify personalistic leadership, this document does it.Footnote 29

Conclusion

When we look back over the four decades of the reform era, we see an important cycle, starting with Deng Xiaoping's efforts to correct the enormous failures of the Mao period by strengthening Party discipline and purging those he regarded as factionalists. Deng was an institutionalist in the sense that he hoped to make the CCP function in ways that would bring about political stability and economic growth by regularizing Party processes. But Party discipline without third-party enforcement is not institutionalization, and the institutions that could normalize leadership and leadership succession could not be created without destroying what made the Leninist party function – including personalized leadership. So rather than witness the institutionalization of the Party, as many analysts have held, we have witnessed a process during which each successor has tried to personalize power by appointing close followers.

Deng hoped that he could create a basis for long-term political stability by decreeing that Jiang Zemin could rule for two terms (plus the remaining years of Zhao Ziyang's term) and then turn power over to Hu Jintao. Deng was clearly trying to establish a system in which a leader could not choose his successor, so power would not be overly concentrated and no wing of the Party would feel left out (because power would alternate between wings). But one could not rule China – or even feel secure in power – without building personal power. By the time of the 16th Party Congress in 2002, Jiang had built sufficient personal power that Hu Jintao could never grasp the tools he needed to rule effectively.

By the time of the 18th Party Congress, Party dysfunction was real and deep, as corruption metastasized, local Party networks expanded, society diversified and a middle class developed. “Peaceful evolution” was a palpable danger to the CCP. The CPSU had collapsed in 1991, and the “colour revolutions” of Georgia and Ukraine had occurred in 2003 and 2004. The danger to the Party was real, although Xi appears to have exaggerated those fears to promote his own agenda. Xi's campaign against corruption was not only intended to reinforce Party discipline and to rid the Party of powerful opponents but also to undertake a wide-spread “reform” of the Party – removing the interference of Party elders, reducing the importance of the CYL, bringing the military under Xi's personal control, strengthening the role of the Party's disciplinary organs, and enhancing the Party's role throughout society. In short, the balances that had once moderated the Party's worst impulses, even as they created tensions within the Party, were reduced or removed, allowing Xi to centralize power in himself.

As Xi has personalized power, he has also undermined the possibility of any sort of third-party enforcement, which is the sine quo non of institutionalization, and has thus impeded the possibility of regularized political succession in the future. One of the most poignant lines in Deng Xiaoping's works is his statement that if systems are bad, “they may hamper the efforts of good people or indeed, in certain cases, may push them in the wrong direction.”Footnote 30 Deng hoped to create a system that would push leaders in a good direction, but he attempted to do so by strengthening Leninism. But Leninism was the problem, not the solution. By trying to re-invigorate Leninism, Xi Jinping has recreated the problems that the reform movement faced at the start: a highly centralized and personalized system. One hopes that Xi will not repeat the errors that Mao made, but Xi's felt need to rely on nationalism to sustain his own authority and that of the Party has brought domestic and international tensions that seem counter-productive from China's own perspective.

The biggest problem that this reversion to centralized, personalized rule creates is that it seems particularly ill adapted to an increasingly complex Chinese society. Since reform began in 1978, the economy has grown some 23 times, reaching over $10,000 per capita, the urban population has reached over 60 per cent of total population, the private economy produces some 60 or 70 per cent of all goods, and there are over half a million officially registered non-governmental organizations (NGOs), with many more unregistered.Footnote 31 Despite surveys that show a high-level of “trust” in the state, surveillance of the population continues to intensify.Footnote 32 Perhaps the crackdowns on the Ant Group and Didi will result in a healthy regulatory system, but more likely they will dampen entrepreneurship and innovation.Footnote 33 Moreover, failure to deepen reform has slowed productivity and economic growth, particularly in the state-owned sector.Footnote 34 It appears that the effort to reduce dependence on foreign technology, embodied in “Made in China 2025,” and the recent endorsement of a “dual-circulation” economy will have to swim upstream in this environment.

Replacing the relative openness of previous years with the cultivation of nationalism and “wolf warrior” diplomacy may provide a temporary boost in legitimacy, but it does not appear to be a long-term solution. China's treatment of Uyghurs, its suppression of free speech and rule of law in Hong Kong, and its threats to use force against Taiwan similarly create tensions that are not in China's own interest. The rise of China is often depicted as both inevitable and unstoppable, but the failure to institutionalize its governing system points to very real governance issues. The Party has survived for 72 years in power, but that longevity is owing more to its pervasiveness, its ability to foster prosperity and the decentralizing reforms instituted by Deng Xiaoping than it is to institutionalization. Maintaining the Party as a mobilizational party with only weak institutionalization has allowed it to maintain a monopoly on power, but it has also prevented the sort of institutionalization that might avoid the sort of governance problems that are accumulating, one of which is the succession issue, which will certainly be exacerbated if Xi stays for a third term (or more).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Joseph FEWSMITH is professor of international relations and political science at the Boston University's Pardee School of Global Study. He is the author or editor of many books, including, most recently, Rethinking Chinese Politics (2021). Other recent works include The Logic and Limits of Political Reform in China (January 2013), China since Tiananmen (2nd edition, 2008) and China Today, China Tomorrow (2010).