In March 1990, shortly before the first competitive elections in the history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Washington Post reported, “Erich Honecker, East Germany's disgraced Communist chief, is now believed personally to have enriched himself with cocaine dealings.” The article went on to say that details remained vague, but Western intelligence believed that Honecker had personally made at least $75 million importing cocaine for sale to the West. The journalists even claimed that Honecker sought to preserve the Berlin Wall to maintain his hold on the drug trade because he knew it was “essential to his own drug profiteering. Without it, East German officials would lose control over traffic across the border.” The former leader of the Socialist Unity Party (SED), taking refuge in a vicarage just outside East Berlin, faced possible criminal charges for his role in the lethal border regime meant to stop human traffic across the East German border. Now faced accusations of further criminal activity for allowing too much cross-border traffic of another kind.Footnote 1

From the late 1960s onward, East Germany did in fact act as a transit country for the illicit trafficking of drugs into the Federal Republic, but the reality on the ground was much more complicated than the paranoid tropes of Western Cold Warriors. The SED was horrified by narcotics and viewed them as a sign of Western moral and social degradation.Footnote 2 Far from a plot to destroy the West, the problem of drug smuggling via the GDR reflected an embarrassing inability of East German customs and border agents to completely interdict the tenacious network of traffickers, both amateur and professional, that aimed to bring hashish and heroin into West Germany and beyond. Just as East German society was decisively shaped by the border regime enacted by the SED to prevent people getting out and Western influence from getting in, the GDR was also shaped—both domestically and in foreign policy—by the illicit narcotics that were smuggled across its borders to the West.Footnote 3

Politically and ideologically, the SED succeeded in creating a global role for the GDR through international solidarity movements and direct aid to revolutionary parties and socialist states across the Global South. Yet it always struggled to integrate the country into the globalizing economy; until its collapse, access to international consumer goods from blue jeans to coffee remained a perpetual issue delegitimizing the regime.Footnote 4 From the standpoint of illicit drugs, however, a very different narrative emerges. International traffickers had little interest in the East German market due to the lack of customers with access to hard currency: drugs such as cannabis, heroin, and cocaine are illicit goods, but they are also commodities produced, distributed, and purchased as part of a globalizing economy that was similarly out of reach of the average East German.Footnote 5 Viewed as globally traded commodities, the traffic in narcotics represented an illicit form of “alternative globalization”: East Germany acted as a transit corridor between producing countries in the Middle East and central Asia and the lucrative consumer countries of western Europe.Footnote 6 Similar to the effects of prohibition enforcement elsewhere, East German participation in the global anti-narcotics system not only drove the professionalization of smuggling, but also increased the profits that could be made by trafficking drugs to a relatively isolated pocket of consumers such as in West Berlin, located in the heart of East Germany.Footnote 7 The Allied occupation of Berlin during the Cold War created exploitable ambiguities of sovereignty and control over the boundaries between the GDR and the western sectors of the divided city.

Narcotics enforcement revealed the spatial conflict between the geography of the Cold War—where the GDR was at the front line of an intractable ideological conflict between East and West—and the international drug prohibition system, which sought global interstate cooperation in the name of a “universal international society,” against the common threat of criminality.Footnote 8 In the early years of the Cold War, both sides integrated the fight against narcotics into a Cold War framework, attributing abuses to the evil of their rivals. American antidrug warriors imagined narcotics trafficking as part of a global communist plot, whereas East German officials understood international smuggling as a problem of capitalist social decay expanding outward from West Germany.Footnote 9 For the SED, joining the international community to stop this traffic was understood as a means of containing a pathology of Western life. In the 1970s, however, the mutual reinforcement of the drug war and the Cold War began to break down as experts on both sides of the Berlin Wall began to look positively at the prospect of East-West cooperation to suppress the common threat of international drug traffickers.Footnote 10

Despite American and West German protests about the inhumanity of the GDR border regime toward its own citizens, the East German border actually became a site of collaboration among the three states, with the common goal of the increased policing of suspected drug traffickers from the Global South. The conflicting geographies of the Cold War and the drug war were resolved in the 1980s by the GDR's move away from associating narcotics with the corruptions of Western capitalism and toward a strategic partnership with the West as fellow countries beset by traffickers from the Global South.Footnote 11 The SED's fight against narcotics and its ongoing fears about drug traffic across the borders of the GDR demonstrate the double-edged nature of East Germany's connections to the outside world—which the SED saw as both necessary but also existentially threatening to the GDR as a socialist state—and the central role of the border as an institution mediating those encounters with the rest of the world.

The GDR's Semi-Integration into Global Narcotics Networks

At the Zinnwald-Cínovec border crossing on the highway from Prague to Dresden, East German customs agents made their first drug seizure since the building of the Berlin Wall at 8:20 am on April 29, 1968, when a young Yugoslavian student was arrested with forty-six grams of hashish.Footnote 12 He had apparently acquired the drugs in Sweden, where he worked in a Stockholm café, before driving to Belgrade for a visit, and then got caught on the return trip. The next case came in 1969, when a student from West Berlin was apprehended at the Rudolphstein-Hirschberg crossing between the East German district of Gera and West German Bavaria with a mere four grams of hash. The other ten cases that year were very similar: almost all had only enough for personal consumption, were moving between West Berlin and West Germany, and were Germans whose profession was usually listed as “hippie.” The only exception was an unfortunate Istanbul-born sailor from West Berlin who forgot he was carrying two grams of hash when he decided to go dancing in the capital of the GDR. The largest amount seized was from a twenty-one-year-old, caught with 174 grams of hash and 2 grams of opium that he picked up from a pop and blues festival in the western city of Essen before returning to West Berlin via the Helmstedt-Marienborn train crossing at the border of Braunschweig in the Federal Republic and Magdeburg in the GDR.Footnote 13

Although there had been only eleven drug seizures at the border in two years, it was seen as a burgeoning crisis: “Every successful transit of narcotics through the territory of the GDR is a blatant violation of the sovereignty of the GDR,” declared one study on drug smuggling produced for the criminology department of Humboldt University.Footnote 14 Framing trafficking as an attack on East German sovereignty echoed state language that described illegal border crossing by individuals as well as crimes punishable by the death penalty under the criminal code.Footnote 15 There was no evidence of Western complicity, but drugs were deemed one of the dark tools employed by the agents of imperialism, as evinced by US chemical warfare in Vietnam.Footnote 16 The Humboldt study blamed not only hunger, discrimination, the absence of rights, and other general problems of late capitalism as root causes of drug abuse, but also the emerging counterculture, including hippies, beats, the “pop-movement,” and “dropouts” (Gammlertum). Far from being allies of the East German state, these groups were understood to be a fake opposition that did not threaten the power structures of the capitalist system and whose communes could be falsely linked to the socialist bloc for propaganda purposes.Footnote 17 Although there were a few long-haired hippies who did try to live a nonconformist life in East Germany, they had been targeted politically and legally by the SED as dangerous “asocials” since 1965, the same year that recreational drug usage had taken off in the West.Footnote 18

In 1970–1971, the number of trafficking cases at the East German border exploded due to the massive expansion of drug smuggling across Europe. In 1970, the number of cases skyrocketed to 328 seizures totaling 142 kilograms of narcotics, all but 1 kilogram of which was hashish. Seizures at the border, almost all hashish, nearly doubled in 1971, to almost 211 kilograms.Footnote 19 Fewer than 10 percent of border seizures concerned traffic in the direction of the GDR, and seemingly all involved very small quantities brought from West Germany or West Berlin.Footnote 20 Although the largest group of smugglers caught at the border was composed initially of West Germans (or West Berliners), many of whom were students transporting small quantities, already by 1970 there were several cases that demonstrated that the GDR was now part of a globalizing network of trafficking.Footnote 21 By land, East Germany was now an obscure side road on the hippie trail: the counterculture route traveled from Europe to Nepal and Afghanistan.Footnote 22 For example, a young mail courier from Amsterdam was caught at the border with more than five kilograms of hashish that he had purchased in Peshawar, Pakistan, for $72. From Pakistan, he had driven a car registered in West Berlin through Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, only to be busted crossing into the GDR at the Zinnwald-Cínovec crossing on his way to West Berlin, a stopover en route to his final destination, Amsterdam, where he planned to sell the hashish at the Club Paradiso.Footnote 23 In another case, a Jordanian engineer was arrested at Schönefeld Airport in East Berlin with 5.8 kilograms of hashish that he was supposed to deliver to the Hotel Steinplatz in West Berlin. He had traveled to the capital of the GDR on a Hungarian airline from Damascus by way of Nicosia, Athens, Budapest, and Vienna and been paid 5,000 Deutsche Mark, along with the cost of the flight and the promise of a hotel room in West Berlin upon arrival.Footnote 24

This collection of small-time international smugglers would soon be joined by more professional operations that aimed to bring in bulk quantities of hashish to West Berlin via Schönefeld Airport, making it the main conduit for drug trafficking in the GDR until the fall of the Berlin Wall.Footnote 25 East Germany's Interflug Airline had expanded its routes from other Eastern bloc capital cities to include neutral and nonaligned Europe as well as North and West Africa and the Middle East.Footnote 26 Although a larger number of seizures occurred at the border checkpoints between West Berlin and West Germany, these were usually only a few grams for personal consumption, and offenders were often released with only a fine. At Schönefeld Airport, there were fewer individual seizures, but amounts were usually much larger (around fourteen to twenty kilograms of hashish), and the smugglers were almost all non-German. In 1971, the thirteen trafficking cases from the airport leading to criminal prosecution included five suspects from Lebanon, three Jordanians and Palestinians, and one each from Sudan and the United Arab Republic (the short-lived union of Egypt and Syria).Footnote 27 Approximately half the cases involved some form of organized crime, which provided the smugglers—many of whom were unemployed and needed the money—with luggage that had hidden compartments. In one case, the son of an Indian general (who claimed to have been blackmailed by an organized crime group) had traveled by plane from India to Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and then Czechoslovakia, where he boarded a train bound for West Berlin via the GDR.Footnote 28 Others arrested included a bar hostess, a West Berlin police officer, and a pair from a “militant African Maoist group,” seeking to sell marijuana in France to finance the revolution back home.Footnote 29

The emergence of drug smuggling led GDR authorities to reform their border control practices, which had previously been oriented around preventing emigration, illicit currency exchange, and the unauthorized export of valuables such as precious metals.Footnote 30 In 1969, a directive was sent to all customs agents warning them to be on the lookout for drug traffickers. After West Berlin newspapers published stories on two high-profile hashish seizures, where smugglers from Lebanon and Syria were apprehended after crossing to West Berlin on a bus direct from Schönefeld Airport in East Berlin, GDR officials undertook a review of customs and anti-smuggling procedures for incoming air passengers.Footnote 31 The Humboldt criminology study from that year recommended that customs agents be on the lookout for beats, hippies, and dropouts, but also those traveling from “narcotics countries” in “the Far East, South East Asia, the Middle East, North and West Africa” looking to go to West Berlin or Scandinavia. Recognizing that this covered a vast population, the author recommended extra scrutiny for those who seemed to be traveling the route with suspicious regularity.Footnote 32 The following year, the chief customs inspector issued new service instructions on “measures to detect and prevent the import, export and transit of narcotics across the state borders of the GDR,” outlining procedures for inter-agency coordination, standardized criteria for drug arrests, and the requirement to immediately report all narcotics seizures to higher authorities.Footnote 33

These drug busts were not publicized in the GDR, but the threat of narcotics trafficking emanating from the West became a common theme in East German public culture. GDR officials took pride in the idea that there was no drug scene in the East, and narcotics abuse was consistently depicted as a social issue exclusive to the capitalist West or part of traditional cultures in the underdeveloped South.Footnote 34 Yet as early as 1967 (a year before the first drug seizure at the GDR border had even taken place), the state film production company DEFA began shooting Heroin, a film about the heroic East German customs officer, Kommissar Zinn, who works with Hungarian and Yugoslavian comrades to foil a drug smuggling ring running through East Berlin led by a pair of Frenchmen.Footnote 35 When the show Customs Investigation (Zollfahndung) premiered on GDR television in 1970, an early episode centered on a West German pop singer trying to smuggle heroin to West Berlin from Hamburg via East Germany.Footnote 36 GDR media coverage of international crime highlighted the role of ostensibly respectable Westerners in the drug trade, including a German law student convicted by a Lebanese court for having thirty-five kilograms of hashish in his car, US military personnel arrested in Southeast Asia smuggling heroin, and the New York police accepting bribes from mafia-connected drug dealers.Footnote 37 In keeping with the perception of drugs as a covert weapon of the imperialists, the East German press also reported on CIA involvement in opium production in Laos and the arrest of a French secret agent smuggling forty kilograms of heroin.Footnote 38 Although the socialist order forestalled the causes of drug abuse afflicting the capitalist world, narcotics were still viewed as a possible threat that could infiltrate and undermine life within the borders of the GDR.

The SED's response to international narcotics trade revealed the simultaneous drive for the GDR to integrate more fully into global affairs in the 1970s and the fears of increased Western influence. The threat of drug smuggling was imagined as an element of East Germany's position on the frontline of the Cold War, and the response was ideologically integrated into the SED policy of Abgrenzung—the demarcation of the socialist East Germany from its Western imperialist counterpart—formally adopted at the 8th SED Party Congress in 1971. With the increasing engagement from West Germany as the result of new policy of Ostpolitik, the SED had begun to foster a more entrenched sense of East German identity, including the creation of a separate GDR citizenship and a new “socialist constitution” in 1968.Footnote 39 As the traffic in hashish through East Germany exploded, the politically influential intellectual Jürgen Kuczynski wrote:

Yes, we consciously draw a line between ourselves and the plague, between life and death … “Demarcation” [Abgrenzung] a word our enemies hate just like the “wall” that we built ten years ago in one night to defend against their attacks! Demarcation against everything that is harmful to be smuggled into our country, against drugs and ideological perversion, against hash and heroin, against nationalist reaction and social democracy.Footnote 40

Narcotics served as a metonym for the threat of Western influence coming across the border, which equated the poison of drugs with the poison of capitalist culture. To allow drugs to freely cross the border would be to abandon the broader defense against Western infiltration and subversion.

If narcotics trafficking required separation from the West, SED officials also decided that it demanded further integration into the previously ignored global narcotics control system of the United Nations. In the immediate postwar period, the GDR established a Central Opium Office, responsible for reporting on drug imports and exports, which had been created by the Soviet Occupation Authority to comply with prewar League of Nations drug conventions signed by Weimar Germany.Footnote 41 In 1958, the SED affirmed that it would abide by the prewar conventions, but East German officials seemingly made no effort to influence the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotics—the first truly global legal agreement on drug control—in contrast to the Federal Republic, which was one of seventy-three states that negotiated its terms. In 1969, the Federal Republic's diplomatic blockade broke down, clearing the path for the GDR's wider recognition outside of the socialist bloc, culminating with its entry into the United Nations in 1973 and near-universal recognition of the GDR following the Helsinki Accords in 1975.Footnote 42 Although the GDR was again too late to take part in the negotiations of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, East German officials decided that year to implement a raft of legal changes to update the regulation of narcotics. Because the overhaul of the criminal code in 1968 had not actually included narcotics offenses (because drugs were no longer a problem in the GDR), and the new code effectively invalidated earlier drug legislation including the 1929 Opium Law, the only legal recourse between 1968 and 1973 was to arrest traffickers on smuggling and customs violations charges instead of drug charges.Footnote 43

The key law passed to deal with the surge in narcotics trafficking was the Addictive Substances Act of 1973, which created the Central Bureau for Addictive Substances, based in the Ministry of Health, which replaced the postwar Central Opium OfficeFootnote 44 and formally assigned responsibility for policing criminal drug violations to Section II (Investigative Services) of the Customs Enforcement Department, under the supervision of the Stasi's Main Division XVIII.Footnote 45 This was followed by a ratification of both the 1961 and 1971 UN narcotics conventions in 1975.Footnote 46 According to the Ministry of Health, which spearheaded the reforms, this was a matter of global politics: it was vital for the GDR to refute claims circulating in West German media that the SED tolerated drug trafficking for profit and to reinforce East Germany's conformity with the norms and values of the United Nations and the World Health Organization as a member of the global community. Simultaneously, these regulations were needed to foster ties to the global economy and were justified as a necessity for the GDR, as an “important country for travel and transit in Europe,” to secure the transit of licit pharmaceuticals and hinder the traffic in illicit narcotics. Specifically, the East German chemical and pharmaceutical industries and their capacity to export to the socialist and nonsocialist world required clear legal regulations.Footnote 47 Narcotics control was thus a means of mediating East Germany's relationship with the rest of the world at its borders, allowing for a clear distinction between good forms of cross-border international trade and exchange and the criminal prosecution and control of illicit forms of drug trafficking.

The Heroin Wave and Western Panic about the GDR Border

Although trafficking across the GDR border was a crisis for the SED, it initially barely registered in the West. Early Cold War claims by American antidrug officials that communists were behind the global drug trade were largely abandoned upon US President Richard Nixon's opening of relations with the People's Republic of China.Footnote 48 According to West German law enforcement, there were twelve reported drug seizures from people crossing the border from the GDR into West Berlin in 1970, but this paled in comparison to the sixty-four seizures at the Swiss border, forty-nine with Austria, thirty-five with France, and thirty-two with the Benelux countries. Only Denmark was a lesser problem, with only two incidents.Footnote 49 West Berlin was also not considered a major smuggling hotspot among West German cities: in that same year, 180 kilograms of cannabis was seized in West Berlin—compared to 264 kilograms in Freiburg, 663 kilograms in Hamburg, 822 kilograms in Munich, and 1,428 kilograms in Frankfurt.Footnote 50 American authorities also took a particular interest in drug trafficking in the Federal Republic due to media reports that drug use was rampant among its 185,000 soldiers stationed there.Footnote 51 This was primarily blamed on the failure of local police to stop overland shipments from entering Bavaria at the border crossing with Austria as they transited from their origin in Turkey to destinations in southern France.Footnote 52

As traffic between East and West Germany increased after their mutual recognition through the Basic Treaty in 1972 and the Helsinki Accords in 1975, the movement of non-Germans across this border began to raise alarm. The West German Customs Investigation Service could not operate on the boundary to the Soviet Sector of Berlin, but did monitor how the East Germans were handling trafficking on their side of the line. Reports noted that drug searches including the use of sniffer dogs and baggage checks had been implemented at Schönefeld Airport. Most importantly, East German customs had effectively stopped smuggling from its side of the Waltersdorfer Chaussee border crossing, which allowed West Berliners and foreigners to travel from Schönefeld to West Berlin via a short bus connection. Far from ignoring the problem of narcotics smuggling, West German customs had reports of arrests and major seizures of hashish at the airport—the fact that one smuggler was sentenced to seven years imprisonment was taken as a sign that the crime was being handled seriously, in contrast to the Weimar-era Opium Law, which had until recently capped such punishments at three years. This matches East German records, which showed a drastic decline in seizures after the high in 1971 to a range of fifteen to eighty kilograms a year.Footnote 53

In 1975, intelligence gathered from suspects in the West now pointed to a new system of smuggling from East to West Berlin via the checkpoint at the Friedrichstraße train station. Because West Germany and the Western Allies refused to accept that this border was an international boundary (as it connected the Soviet sector of occupied Berlin to the western sectors), checks were conducted only by GDR officials, whose priority was to prevent the unauthorized emigration of East Germans and ensure travelers were in conformity with GDR currency controls. Smugglers would take their product from the airport to a train station locker and then meet clients at international hotels around Alexanderplatz in East Berlin to sell the locker key to the Western buyers.Footnote 54 When West Berlin officials wrote to the various West German government ministries tasked with drug enforcement to ask that the East Germans be contacted directly with this information in order to convince them to more effectively police trafficking at Friedrichstraße, West German officials confronted the question of how to do so.

West Germany had already established police working groups to coordinate more closely with France, Turkey, and the Netherlands, but cooperation with the GDR was much more complicated.Footnote 55 The 1972 Basic Treaty had established mutual recognition, but stopped short of full diplomatic exchange, and the special status of Berlin remained politically sensitive as the city lingered under four-power occupation by the Allies, but with East Germany claiming the Soviet sector as its capital city and an integral part of its territory. A precedent existed for reporting specific imminent threats to the East German police, but requests for preventive enforcement against a general criminal activity did not fit that mold. Another option was to contact the permanent representative—the equivalent of the ambassador—but this could elevate the matter to a full-blown diplomatic incident. The final option was to treat the problem as a health issue. After signing the Basic Treaty, the first agreement between the GDR and the FRG had been the Health Accord, which included provisions on public health information sharing between the countries. Article 6 of the agreement specifically mentioned the “spread of the abuse of narcotics and other addictive substances,” but no one had yet tried to use this for anti-smuggling purposes.Footnote 56

The West German Ministry of the Interior rejected the possibility of directly contacting the East German police, and the wider ministerial consensus held that the Ministry of Health, Families and Youth should act as the messenger. In coordination with the Chancellor's Office and the Ministry for Inner-German Relations, they drafted a note to inform the East German Ministry of Health of the problem without making any accusations of complicity with the traffickers: “According to the information available, drugs are traded on the premises of the Friedrichstraße train station. There are numerous indications that members of Arab states, who often refer to themselves as Palestinians, smuggle narcotics, preferably hard drugs, into West Berlin in this way.”Footnote 57 The letter went on to acknowledge the extra efforts made by East German customs to secure the Waltersdorfer Chaussee crossing (between Brandenburg and West Berlin) against smugglers, and provided details about the use of the train lockers and hotels for dealmaking. The GDR responded with boilerplate language, without addressing the issues raised directly, but the West Germans did receive reports that the security services were acting on the information they had provided.Footnote 58 This effort at using the Health Accord as a tool for quiet anti-narcotics cooperation was partially successful, but the issue would not remain in the backroom for long.

Successful American interdiction operations against the Turkey-to-Marseille drug pipeline known as the “French Connection” opened up a vacuum that was filled by drug traffic from Southeast Asia via major international airports such as Frankfurt, Munich, and Amsterdam, as well as on land via the so-called Balkan Route, running along Route E5 from Turkey to the Schwarzbach Autobahn in Bavaria via Southeastern Europe.Footnote 59 A surge in heroin overdose deaths in West Berlin, however, suddenly made the GDR border into a central theater in the drug war. Although there were twenty-nine illicit drug-related deaths a year in the entire Federal Republic at the start of the decade, there were eighty-four deaths from heroin overdoses in West Berlin alone in 1977.Footnote 60

The sharp rise in heroin-related deaths was blamed in the media on the combined threat of resident ethnic minorities and the incompetent East German authorities who enabled them. Die Zeit labeled West Berlin “the capital city of the fixer,” blaming lax controls at Schönefeld and quoting an anonymous judge saying that courts were overwhelmed with cases of dealers that often involved “Turks and Arabs.”Footnote 61 The West Berlin Senate publicly agreed with these accusations, and, in the Bundestag, Kurt Spitzmüller of the Free Democrats (FDP)—the junior partner in the governing social-liberal coalition led by the SPD—proclaimed, “obviously, numerous people involved in drug smuggling from the Middle and Near East come to East Berlin via East Berlin's Schönefeld Airport and from there to West Berlin,” where “the mass of Turkish guest workers in West Berlin—the Kreuzberg district—has created a dangerous breeding ground for such drug-related crime.”Footnote 62

The widespread panic about heroin in West Berlin did reflect the growing problem of heroin deaths, but the West German Ministry of Health, Families and Youth disputed the focus on the divided city. Seizures there were not out of the ordinary (compared to other major cities), and local prices remained high in contrast to Frankfurt (which appeared to be the main air connection for traffickers), indicating difficulties for dealers in meeting supply.Footnote 63 The fears of an uncontrolled border with East Germany also reflected a shift from the widespread social anxieties surrounding the drug-associated counterculture in the late 1960s and early 1970s to a broader social unease surrounding foreigners and East Germans with whom coexistence was now a permanent feature of everyday life.Footnote 64 In 1973, West Germany ended the program of bringing in guest workers in response to the oil crisis and the subsequent economic downturn. Rather than leaving, a substantial minority of guest workers stayed and sent for their family members.Footnote 65 By the outbreak of the heroin wave, it had become generally accepted, if grudgingly, that these groups would be integrated into West German society.Footnote 66 At the same time, however, the state apparatus began to more closely connect foreigners with crime: the courts began to collect information on convictions of “non-Germans,” and, in 1978, the police began to publish statistics on “crime by foreigners” (Ausländerkriminalität).Footnote 67 Although diplomatic relations between the two Germanys had been largely established by that point, the GDR remained the communist other to the Federal Republic's democratic Rechtsstaat, making it a natural scapegoat and villain for the sense that the state was losing control and the social order was breaking down.

East German media countered the allegations that the GDR was complicit with drug trafficking by interpreting them as a mere attempt to deflect blame from the failings of the capitalist system. In an interview with a West German newspaper, one East German official denounced how the “plague of imperialism” was being made into a “problem of the socialist states.”Footnote 68 In the international affairs magazine horizont, one author wrote: “On all other matters there are constant accusations ‘you police too much,’ and now it is all of a sudden, ‘you police too little!’” The “campaign of libel” against the GDR and Schönefeld Airport in particular represented little more than envy at the competition offered by East Germany's Interflug airline. Moreover, “Every traveler can observe that our customs authorities are meticulous in fulfilling their duties—unlike the thoroughly corrupt customs agents of West Berlin.”Footnote 69

The conflict escalated the following year when American congressman Glenn English, a Democrat from Oklahoma and chair of a taskforce on drug abuse, claimed that East Germany was a “silent partner” to drug traffickers. Despite the alleged 7,000 pounds of heroin a year being shipped through the GDR, English said, “They're taking no steps to intervene.”Footnote 70 The American Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) publication Drug Enforcement reinforced these accusations: “Mid-East heroin is flowing with little disruption through East Berlin.” It blamed the Turkish nationals residing in West Berlin for taking advantage of lax customs controls by “East German border officials [who] reportedly seem more interested in identifying persons engaged in suspicious anti-state activity than stopping drugs being smuggled to the West.”Footnote 71 On the ground, however, the Narcotics Commissioner in West Berlin said there was no evidence that Schönefeld Airport was the problem given checks on public transit near the border crossing from the GDR yielded almost no drug seizures. He argued it was more likely that drugs were coming in through West Berlin's Tegel Airport or by car and truck on overland routes.Footnote 72 Yet American officials and West German media had suddenly transformed the border with the GDR and Schönefeld Airport in particular into a hotspot in the global war on drugs.

The Difficult Path to East-West Anti-Trafficking Cooperation

Although officials in both Germanys and the United States all had a strong interest in working together to secure the GDR border against narcotics trafficking, the geographies of the Cold War and the global drug war were incompatible. The Cold War logic of a bipolar world divided between the communist East and democratic West mapped poorly onto the actors of the global drug trade, which included everyone from nonaligned substate criminal gangs to CIA-backed anti-communists in Asia and Latin America and elements of the Bulgarian and Cuban security services.Footnote 73 As a result, efforts by narcotics officials to foster cross-border collaboration continuously ran into roadblocks as their plans hit up against the Cold War prerogatives of other parts of their state and bureaucratic apparatuses.

Nonetheless, as Berlin became the new public frontline in the drug war in the late 1970s, circumstances in the GDR, West Germany, and the United States aligned to create new opportunities for cross-border collaboration. On the East German side, there was clear interest in international collaboration on the part of Ulrich Schneidewind, the effective head of GDR narcotics policy. An SED member with a doctorate in pharmacy, Schneidewind was head of the health department's section on pharmaceutical and medical technology before becoming Deputy Minister of Health in 1982. He had been one of the architects of the reformed East German drug system, supervised the operations of the Central Bureau for Addictive Substances, and represented the GDR at international events on illicit narcotics and trafficking. For the West Germans, narcotics trafficking quickly replaced international terrorism as the new threat to the Federal Republic following the decline of the Red Army Faction after 1977.Footnote 74 German Federal Police Chief Horst Herold announced a plan for a “war at the Dardanelles” against the influx of drugs from Turkey by repurposing the massive computer data system developed to track down the Red Army Faction to map the drug trade with the help of international allies.Footnote 75 At the same time in the United States, President Jimmy Carter's administration was trying to reach out to communist countries to find common ground through cooperation on drug interdiction. As part of the negotiations on a clear maritime boundary with Cuba, the US State Department included provisions on a cooperation to stop Caribbean cocaine smuggling; American customs officials had also been working with Bulgaria since 1971 to train customs agents to more effectively prevent heroin from being smuggled from Turkey and Lebanon.Footnote 76

The public accusations of East German complicity in the heroin trade by a sitting US congressman threw a wrench into plans to bring the GDR into the global US-led drug war. The State Department had organized a conference of customs representatives in Varna, Bulgaria, in September 1978 to initiate a broader East-West collaboration against drug traffickers. The US ambassador to the GDR had even reached out to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs to ask if they could pass along information on suspected traffickers to assist East German drug enforcement. Ulrich Schneidewind had encouraged this plan and justified some form of information exchange with the West on the grounds that a failure to do so could be used against the GDR by its enemies.Footnote 77 But before further steps could been taken, Congressman English's accusations led GDR officials to doubt the sincerity of the Americans. In August 1978, the United States went on a charm offensive to try and get the GDR back on board. While presenting his credentials to President Carter, the new East German ambassador was assured that the United States did not seek to blame the GDR, but instead sought cooperation.Footnote 78 As part of a congressional delegation, English was sent to meet with the GDR's ambassador to the United States and then to East Berlin, where he apologized to Schneidewind by claiming that the information on GDR drug complicity came from concerned constituents in Oklahoma.Footnote 79 The US ambassador arranged for the delivery of rapid drug testing equipment to assist with East German customs inspections.Footnote 80

Yet East German officials remained wary. The US-sponsored conference in Varna had been scheduled on the same dates on which the GDR was supposed to host an annual conference of socialist customs agencies. Although the Soviets saw drugs as an “American problem,” they embarrassingly asked the GDR to cancel its event to avoid the appearance of a split in the Eastern bloc.Footnote 81 In Varna, American officials sought to undo the damage of English's accusations through interpersonal diplomacy. The chief of the DEA's Paris office spoke to the GDR representatives assuring them that his organization did not agree that East Germany was complicit in trafficking, and the US ambassador traveled from East Berlin to Bulgaria to lobby for greater contacts between border agents. The American line throughout the event was that they sought to support the “brotherhood of customs agencies” against a global problem.

East German officials were torn as to whether they would cooperate. On the one hand, they wanted to demonstrate their willingness to fulfill international legal obligations and decided to accept the American offer of information on known traffickers. East German assumptions about traffickers were moving away from a Cold War framing and converging with West German conceptions that traffickers were more likely to be non-German, particularly Turkish or Arab.Footnote 82 The Stasi had informers in the West Berlin Turkish community who reported on drug dealing in East Berlin, including cannabis and valium, and on hashish and heroin trafficking via East German territory. According to the Stasi, the small-scale drug dealing to East Germans—contained to “deviant” communities such as homosexuals and prostitutes—could be blamed on “foreign day trippers,” meaning Turkish guest workers from West Berlin who congregated at a handful of popular cafés in East Berlin.Footnote 83 In contrast to West Germany, however, the Stasi also still saw drug smuggling operations as connected to “human smuggling” operations—namely groups helping East Germans to illegally emigrate.Footnote 84 GDR customs officials also rejected the universalist American framing and saw drug abuse not as a “worldwide problem,” but one rooted “in the misanthropic social system of imperialism.”Footnote 85 East German officials saw this framing as an attempt to make the problem of drugs “class indifferent” and abstracted from the particularities of the competing social orders.Footnote 86 The Stasi in particular remained skeptical after English's accusations and due to the involvement of the CIA in drug policy, which was also seen as evidence of a possible US intelligence plot.Footnote 87 As the conference was taking place in Bulgaria, East German customs officials apprehended a smuggler with 4.5 kilograms of hashish and, fearing it was some kind of test of GDR border controls by the CIA, no decision was made on what to do with him until the event had concluded.Footnote 88 Although the Stasi believed the Americans were motivated by concerns over drugs, they saw the Carter administration's anti-narcotics program as one element in the broader American effort to effect global moral change outside of UN institutions, including the president's anti-communist human rights campaign.Footnote 89 That the initiatives on antidrug collaboration came so soon after major American public pressure on East German human rights violations at the Helsinki Accords follow-up meeting the year before in Belgrade—contrary to the strategy of quiet engagement by West Germany—had further poisoned the well.Footnote 90 After Varna, an immediate follow-up meeting to discuss a new US-GDR bilateral relationship was ultimately rejected by the East Germans.Footnote 91

Although the Varna conference failed to deliver tangible results, both the Americans and West Germans kept trying in the dying days of détente. In 1979, Ulrich Schneidewind was invited to Washington DC to meet with officials from the White House, State Department, Department of Justice, US Customs, and the DEA. Schneidewind reported that they were very frank about the extent of the US drug problem and highly impressed that the GDR had a comprehensive registry of drug addicts.Footnote 92 The White House drug czar Lee Dogoloff reportedly accepted that the GDR had effectively stamped out drug use and argued for their shared interests in working together since the GDR could one day be similarly afflicted by narcotics. Schneidewind's only criticism of the American officials was that they “did not, of course, accept that there was a link between abuse of drugs and the social order—or the ‘free market economy.’”Footnote 93 Although West German officials were able to establish contact with drug enforcement counterparts in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, and Romania, the GDR still eluded them.Footnote 94 West German representatives to a UN meeting in Geneva on drugs also approached Schneidewind about further cooperation and reported that he responded positively about further exchange, but emphasized it could only take place within some kind of legal structure. He suggested that the West Germans raise the issue at the next Health Accord exchange meeting to discuss the matter under the terms of Article 6, but when the representative from the Federal Republic did so, the GDR officials at the meeting had not heard of any such plan and thus could not discuss it further.Footnote 95 Although there was goodwill among individual drug enforcement experts, it was not enough to realize an institutional breakthrough.

In the early 1980s, another wave of heroin-related deaths sparked a panic in West Germany that pushed the new conservative-liberal West German government led by Helmut Kohl to take action on drugs.Footnote 96 The proliferation of international smuggling networks and the rise of Andean cocaine meant that West Germany was now also a destination for traffickers from South America and West Africa.Footnote 97 In December 1983, at a meeting of American and West German drug officials, the doubling of drug-related deaths in West Berlin that year was attributed to more smuggling via Schönefeld Airport. Of particular concern was an influx of trafficking by Sri Lankan refugees, fleeing the civil war in large numbers. Several of them had reported upon their arrest that they had been able to travel directly from the airport to the Friedrichstraße train station (and then on to West Berlin) by means of a “$100” bribe to an East German People's police officer. The DEA believed that the East Germans were simply trying to get the refugees out of their country as quickly as possible, while the West Germans saw a nefarious conspiracy to flood West Berlin with unwanted refugees (and heroin).Footnote 98

Cooperation between the two Germanys should have been made easier by the West German economic bailout in 1982 that forestalled the bankruptcy of the GDR through loans negotiated by Bavarian Minister President Franz Josef Strauss.Footnote 99 Yet that year, the Federal Republic had created a new roadblock when the Narcotics Law (Betäubungsmittelgesetz) took effect. It included a passage ruling that the reporting on—and the customs paperwork required for—the trade in international controlled substances would not apply to (legal) imports from the GDR. This was an extension of a broader West German trade policy that regarded imports from East Germany as a form of domestic, rather than international, trade, which had become entrenched in the European Economic Community policy and was reinforced by the Berlin Convention, an agreement between West Germany and the GDR that underlined the duty-free nature of trade between the two countries.Footnote 100 This agreement masked a fundamental disagreement between the two Germanys—for the Federal Republic, the border with the GDR was a line separating two parts of the German economy, whereas for the SED, the border was an international frontier.Footnote 101 When the narcotics law passed, the SED filed a formal complaint at the United Nations that this non-recognition of the GDR border violated West Germany's commitments to international law.Footnote 102 In a tit for tat, the United States responded that East Germany's claims to total sovereignty over East Berlin also violated international law regarding the continued occupation of all of Berlin by the four Allied powers.Footnote 103

In spite of warnings from the Ministry of Health, Families and Youth that this border question would prevent any kind of collaboration, the West German government sent a note to the East German foreign office with a new proposal for anti-narcotics cooperation. Citing the proliferation of drug crime across western Europe and West Germany's partnerships with other neighbor countries, the note praised the East German anti-trafficking efforts to date while also noting that a West Berlin gang had managed to smuggle five kilograms of heroin over a matter of months via the GDR. As a solution, it suggested a “non-bureaucratic exchange of information” by police and customs in service of the “community of international solidarity.”Footnote 104 West German officials saw the border designation as a technical impediment, but for the East Germans, it was an insulting delegitimization of GDR sovereignty. Top-level East German officials—including Foreign Minister Oskar Fischer, Stasi Chief Erich Mielke, Health Minister Ludwig Mecklinger, and Günter Mittag, the Secretary of the SED's Central Committee—were mixed in their judgment of the proposal. They were positive about the idea of a “substantial contribution” to the fight against trafficking rather than some kind of “spectacular agreement” and saw Article 6 of the Health Accord as a sound legal basis for such an exchange. But they also agreed that the non-recognition of GDR's international border by the recent drug law would have to be changed as a precondition for any collaboration.Footnote 105 The realization of an “ordinary” amount of cross-border cooperation would in fact require an extraordinary shift in West German policy on the status of the border.

The West German government, under international pressure to stem the flow of Sri Lankan refugees through their territory, shifted tactics and sought to link the problem of narcotics to its other initiative to stop the GDR from allowing Sri Lankans to fly into East Berlin (and then on to West Berlin without the requisite visa) in the hope that the immediacy of the problem could shake the East Germans into action. Once again, proposals for cooperation on the matter of the cross-border drug customs paperwork were rejected, as the East Germans understood the West Germans’ discrete problem as an existential threat to their sovereignty, with wide-ranging implications for the internationally recognized status of the border and daily GDR border policy. As a result, the West German government abandoned its short-lived strategy, uncoupled the problem of migration from narcotics, and instead used its financial leverage over the GDR to pressure the East Germans into allowing only those Sri Lankans in possession of a visa for West Germany to enter East Berlin (see Lauren Stokes's article in this special issue).Footnote 106 For West Germany, forcing a limited change in East German migration policy provided clear and immediate results to a specific problem (one actually welcomed by the Stasi to help stem drug trafficking),Footnote 107 whereas the issue of narcotics as a whole opened up too many questions of sovereignty and legitimacy for both sides of the German-German border.

From the American side, the Carter administration's outreach to communist countries had given way to renewed Cold War belligerence under President Ronald Reagan. Backchannel cooperation with Cuba had ended and training programs in Bulgaria were called off.Footnote 108 After declaring a renewed “War on Drugs” in 1982 and ratcheting up domestic law enforcement against drug users, Reagan's 1984 reelection platform denounced “communist dictators” for their role in the international drug trade, singling out the USSR, Bulgaria, Cuba, and Nicaragua.Footnote 109 The DEA, however, dissented from this line, arguing that the Soviets had no role in narcotics trafficking.Footnote 110 On the ground in East Berlin, the DEA and the US embassy continued to try and work out a system of information exchange by framing cooperation with eastern Europe as a means of working together to prevent the misuse of GDR chemicals by Latin American cocaine producers—a common enemy of both the capitalist and socialist worlds.Footnote 111 In 1985, they were able to arrange an expert meeting with DEA specialists and representatives of the GDR foreign office, the Ministry of Health, and the head of the Central Bureau of Addictive Substances in East Berlin. Nonetheless, the East Germans remained unwilling to create a bilateral backchannel to discuss problems with precursor chemicals, purchased legally but diverted to illegal use in third countries (in particular by Latin American drug labs), as this was deemed contrary to the UN conventions, which demanded direct contact with the relevant third state parties.Footnote 112

In the mid-1980s, progress in establishing bilateral anti-narcotics cooperation thus appeared at a standstill, but a shift was underway in how East German officials understood the geography of the global drug war. First, the demarcation between the socialist world and the capitalist world began to collapse as recreational narcotics usage, which had previously been seen as a Western problem, was now on the rise across the Eastern bloc.Footnote 113 Drug abuse in the GDR was still not seen as a social problem, but the SED and the Stasi had growing concerns about low-level trafficking connected to a range of transnational actors who were beginning to supply the domestic market with imported narcotics. Contract workers, refugees, and students in the GDR were all now viewed as possible vectors of small-scale smuggling, which was moving away from small “deviant” niche groups to respectable locations like universities.Footnote 114 In the 1980s, SED concerns about cross-border drug traffic were linked to not only minority groups present in the GDR, but also foreign diplomats (and their families) and even Soviet occupation forces who apparently were caught smuggling drugs from Syria to the consternation of East German officials.Footnote 115 Second, smugglers were also growing more sophisticated. In one presentation to a Stasi investigations unit, a customs inspector complained that organized crime groups from the Middle East were trying to bring drugs through Schönefeld Airport hidden in boxes of foul-smelling fish or shaped into fake cherries or pistachio nuts.Footnote 116 Customs and the Stasi were particularly concerned about the shift from using suitcases with hidden compartments to smuggle drugs to a new generation that also swallowed condoms filled with heroin to evade detection at the border.Footnote 117

This shifting geography of the drug war vis-a-vis the Cold War was reflected in both public policy and public culture. Through negotiations at the United Nations, the GDR and the rest of the Eastern bloc worked with the West to create the 1988 Vienna Trafficking Convention, which called for universal criminalization of drug offenses and created new mechanisms to target international drug smuggling via money laundering rules and the regulation of precursor chemicals used in manufacturing. This was posed as a tool to protect the citizens of consumer states and transit states, including the GDR, from the wave of cocaine smuggling out of South America, but also more generally, from producing countries in the global south.Footnote 118 Public depictions of narcotics in the GDR also changed in this period: although narcotics addiction was ostensibly still an ever-present danger in the West, the image of capitalist states as corrupt forces generating the traffic in drugs shifted toward a portrayal in which they were allies against a global, de-ideologized problem of cross-border crime. While in 1984, GDR state media reported on the mafia's connections to Italian intelligence or on police in Florida who were running a protection racket for drug dealers,Footnote 119 by 1987, the Berliner Zeitung was running coverage with grudging praise for American conservatives and even Ronald Reagan's White House for denouncing Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega's corruption and complicity in the drug trade.Footnote 120 By the end of the year, Neues Deutschland ran an article praising a US-Soviet bilateral agreement on narcotics trafficking cooperation.Footnote 121

By 1988, when the US State Department once again organized an East-West summit on customs and anti-narcotics interdiction in Sopron, Hungary, the reception from Eastern bloc countries was vastly more positive compared to a decade before in Varna. Almost all the state socialist countries admitted to growing drug abuse problems, and the GDR delegate emphasized his country's commitment to bilateral and multilateral cooperation against international drug trafficking.Footnote 123 Rather than focusing on the debauched capitalist countries of the West, the GDR representative saw the Arab states, Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, Jamaica, and Africa (in general) as the main problem areas for law enforcement.Footnote 124 The conference represented a triumph of the American vision of drug enforcement that the East Germans had previously found so ideologically intolerable: this was a meeting of the “brotherhood of customs officials,” discussing how to best secure their borders collectively against the scourge of drugs—without regard to their competing social orders and indifferent to class perspectives.

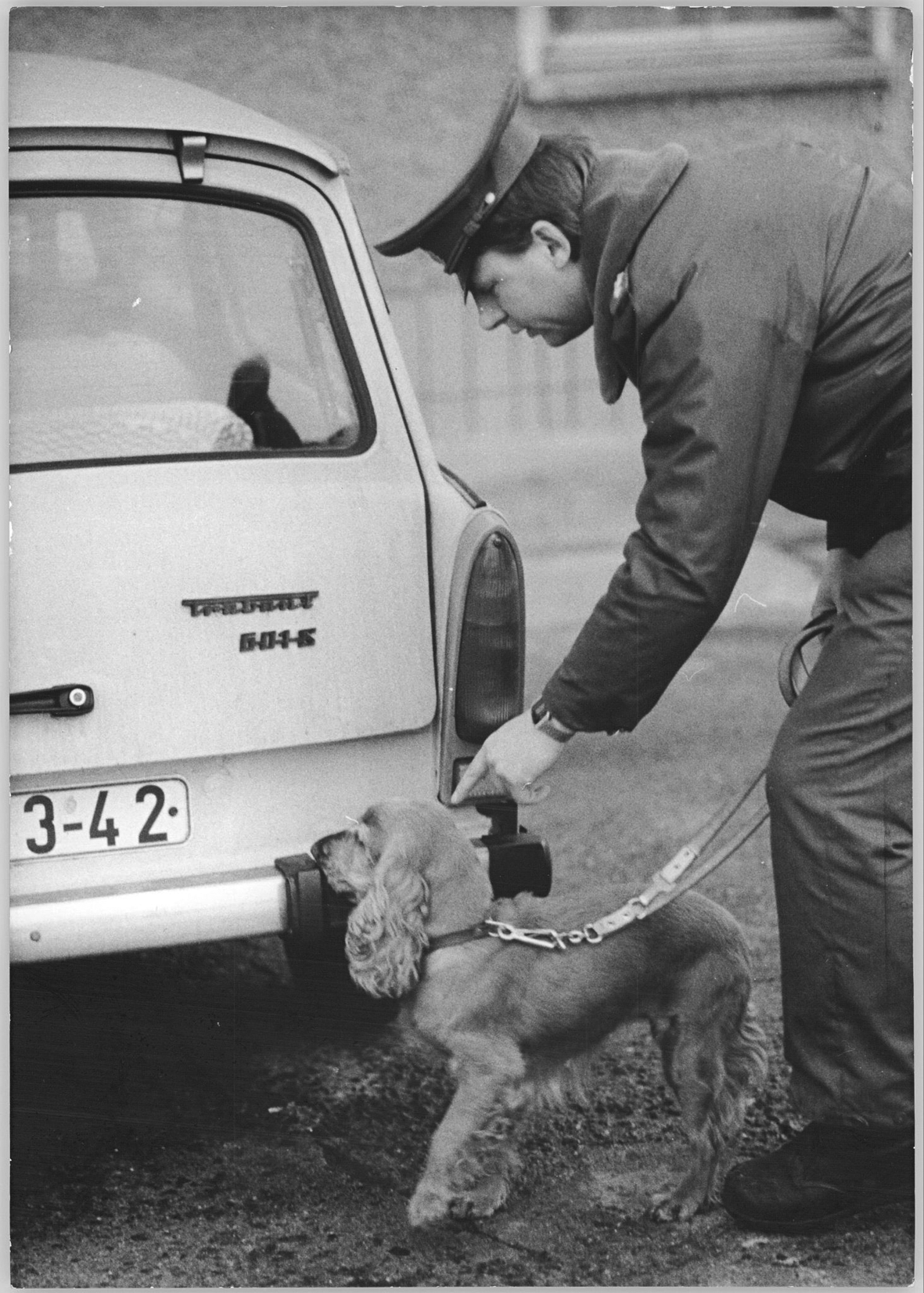

Figure 1. The East German Customs drug detection Cocker Spaniel Jessy checking a Trabant for narcotics at the Heinrich Heine border crossing between East and West Berlin after the fall of the Berlin Wall, November 28, 1989.Footnote 122

By the final year of the GDR's existence as a socialist state in 1989, East German drug officials had reoriented narcotics enforcement at the border toward collaboration with both West Germany and the United States. Over the summer, East German media covered the trial, imprisonment, and execution of high-ranking Cuban military officers accused of collaborating with Colombian drug cartels.Footnote 125 In August and September, the GDR and the Soviets sent representatives to a training seminar in Alexandria, Virginia, run by the DEA; all the while SED control over the country was collapsing and mass demonstrations took hold across the GDR. During a side trip to Fort Meade in Maryland, GDR customs and health officials were given the opportunity to try out the handguns used by the DEA in the fight against Colombian traffickers. Having not completely abandoned their earlier perspectives on narcotics and socialism, the GDR representative expressed disappointment that the training sessions did not include any analysis of the social roots of drug abuse and reported his suspicions that the Hells Angels biker club could be fascist-oriented.Footnote 126 Only a few months later, the day the Berlin Wall fell, November 9, 1989, the director of Stasi counter-intelligence was preparing plans for collaboration with the United States on international drug trafficking.Footnote 127 That day, policing drug traffic across the border was seemingly as much a priority as preventing the total collapse of the border fortifications that maintained the very existence of the GDR as a sovereign socialist entity.

Only a week after the Berlin Wall opened, Neues Deutschland announced the influx of “speculators” into the GDR and the need for a new era of collaboration with West German customs to fight the threat of drug smuggling.Footnote 128 With traffic moving in the other direction, now border guards with drug-sniffing dogs were posted to the crossings in Berlin to stop the flow from West to East (see picture). This was a first step toward the integration of narcotics enforcement between the two countries—even before unification was concluded in 1990. The perceived rapid spread of narcotics across the border led West German media to warn of the “dealer-paradise GDR.”Footnote 129 Far from a haven against the global proliferation of drugs, the GDR was now widely portrayed as needing Western tutelage to secure its border against a new kind of narcotics trafficker, who was targeting the East German domestic market.Footnote 130 A retired head of the West German Federal Police (BKA) was brought in to advise the GDR interior minister on reforms, and the BKA provided assistance to the People's Police when it created its first narcotics unit in May 1990.Footnote 131 The preceding decade of rapprochement between West and East Germany on the problem of policing cross-border drug trafficking served as a prelude to reunified Germany driving the creation of a European Drugs Unit as a stepping stone to the founding of Europol in 1998.Footnote 132 Just as the explosion in recreational narcotics was part of the West German economic boom and rise of youth consumer culture, so too was the proliferation of drug trafficking a part of the full integration of East Germany into globalized market capitalism. The panic over the influx of drugs was also precursor to the widespread fears about the openness of borders ushered in by the fall of the Wall that would proliferate with the rise of xenophobic violence in the 1990s.Footnote 133

The long-standing problem of drug traffickers using the GDR as a transit country and the engagement of East German drug enforcement officials and experts with international initiatives worked to steadily reorient narcotics smuggling from a symptom of capitalist decay to a technocratic issue of law enforcement requiring collaboration beyond the framework of the Cold War. Although the Berlin Wall was the central Western symbol of the suppression of freedom under socialism, the GDR, the United States, and West Germany found common ground on the need for the East German border regime to be even more restrictive, so long as it conformed to the priorities of the global war on drugs.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Anika Weber for her assistance with Bundesarchiv files, Karia Hartung for help with the West German press clippings, and Juana Walheim and Stella Dreber for their work on East German media sources. Thanks to Emily Dufton for putting me in touch with former US Drug Czar Lee Dogoloff, and to Bodie Ashton, Sarah Frenking, and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on the first draft. The research for this article was funded by a Freigeist Fellowship grant from the VolkswagenStiftung.