Introduction

As the proportion of older adults in Canada continues to grow, assistive technologies will continue to play an important role in the promotion of active and healthy aging, independent living, and aging-in-place (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011; Ndegwa, Reference Ndegwa2011; Senate of Canada, 2009; Statistics Canada, 2017a). Although older adults today are healthier and participate more in society than previous generations at their age, evidence shows that as people age they are nonetheless more likely to experience disability (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011; Statistics Canada, 2014b, 2015). Assistive technologies are closely linked with both aging and disability, and 85 per cent of those aged 65 to 74 – and 90 per cent of those aged 75 and older – with disabilities reported using assistive technologies (Statistics Canada, 2015).

Those who are most in need of assistive technologies are people living with a disability (including cognitive impairments and mental health issues), older adults, people with non-communicable diseases, and people with gradual functional decline (World Health Organization, 2016a). The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities promotes equal rights for persons with disabilities, and the role of assistive technologies is pervasive within the Convention’s 50 articles (United Nations, 2006). Canada ratified the convention in 2010 and ratified the Optional Protocol in 2018 (United Nations Treaty Collection, 2019). The 2017 response from the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on the initial report from Canada recognized the barriers related to accessibility and, in particular, the lack of information communication for persons with disabilities (article 9); however, the response from the committee did not outline a specific mechanism for any jurisdiction to take action on improving equitable access to assistive technologies (United Nations, 2017).

In 2014, the Government of Canada issued the first report on the Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which outlines federal, provincial, and territorial policies and programs (including the provision of assistive technologies) to protect rights and support full participation of persons with disabilities (Government of Canada, 2014). Whereas most assistive technologies assist persons with disabilities to help them remain at home and live independently, some technologies (e.g., handrails and portable computers) are designed such that everyone may benefit from their use.

Although assistive technologies are increasingly essential to the home and community care sector, three main challenges limit equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada’s health systems. First, there is variability within and between provinces and territories for the types of assistive technologies that are eligible for funding through government programs. Each province and territory in Canada has different legislation and specifications for what assistive technologies are funded and for whom, which means that many who need assistive technologies are unable to access them. A second challenge is that there is no single program that fully funds the purchasing and provision of the full range of assistive technologies. The eligibility criteria for government-funded assistive technologies is highly variable and may not necessarily be the most suitable to meet the unique needs of individuals. Lastly, despite an increased market supply of assistive technologies, procurement policies and regulatory arrangements have lagged in responding to innovation and growing user demand (Center for Technology and Aging, 2014; Senate of Canada, 2009). For example, manufacturers/vendors/distributors interested in developing and introducing new assistive technologies must apply separately to each province and territory, each of which has different regulatory approval processes.

The result is a complex landscape for both those who need assistive technologies and those who support them (e.g., caregivers navigating the system and/or health care providers attempting to link their patients to services and supports they need as part of their care). These issues can result in the inability to provide for those who need assistance; to meet our society’s responsibilities to ensure that services and opportunities are available in a fair manner; and/or to reduce health care costs.

The way in which assistive technologies are defined within jurisdictions also creates barriers as there are a range of terms used in the field (e.g., assistive device, assistive product, assistive technology device). There is no consensus internationally or nationally on a standard set of terms. For the purposes of our project, we defined assistive technologies in terms of those that maintain or improve the functioning of individuals of any age (Mattison, Wilson, Wang, & Waddell, Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017). The assistive technologies can be available commercially as “off-the-shelf” products (e.g., handrails, shower stools, and electronic/smart technologies); they can require personalized adjustments (e.g., height-adjustable two-wheeled walkers), or they can be customized and designed specifically to meet the needs of the individual (e.g., prostheses, orthoses, and some wheelchairs) (Mattison, Wilson, et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017).

The aim of this project was to spark action towards enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada. Specifically, the project goals were to (a) identify citizens’ views and experiences with, and their values and preferences for, addressing the issue; and (b) prepare action-oriented health-system leaders in Canada by supporting their efforts to enhance equitable access to assistive technologies.

Methods

To meet these objectives, we convened citizen panels in three Canadian provinces followed by a stakeholder dialogue with Canadian policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers. The project was guided by an interdisciplinary steering committee to ensure integrated knowledge translation. The committee consisted of a small number of policymakers, leaders of key stakeholder organizations, and Canadian and international researchers.

Effective citizen engagement and public deliberation can lead to improved outcomes for citizens, policymakers, and policymaking. Improvements include, for example, (a) instrumental outcomes by generating awareness of lived experience and improving the quality of policymaking by ensuring that policies, programs, and services align with the values and needs of citizens (Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles, & Lavis, Reference Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles and Lavis2010); (b) developmental outcomes by providing education and raising awareness about pressing health issues, which also develops citizens’ capacity to take part in public policy matters (Gauvin et al., Reference Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles and Lavis2010); and (c) democratic outcomes by supporting transparency, accountability, trust, and empowerment (Abelson & Gauvin, Reference Abelson and Gauvin2006; Abelson, Montesanti, Li, Gauvin, & Martin, Reference Abelson, Montesanti, Li, Gauvin and Martin2010; Gastil & Richards, Reference Gastil and Richards2013; OECD, 2005; Posner, Reference Posner2011). To inform the deliberations during the panels and to support informed judgments by citizens, we sent a plain-language citizen brief to panellists two weeks prior to the panel (Mattison, Waddell, Wang, & Wilson, Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017).

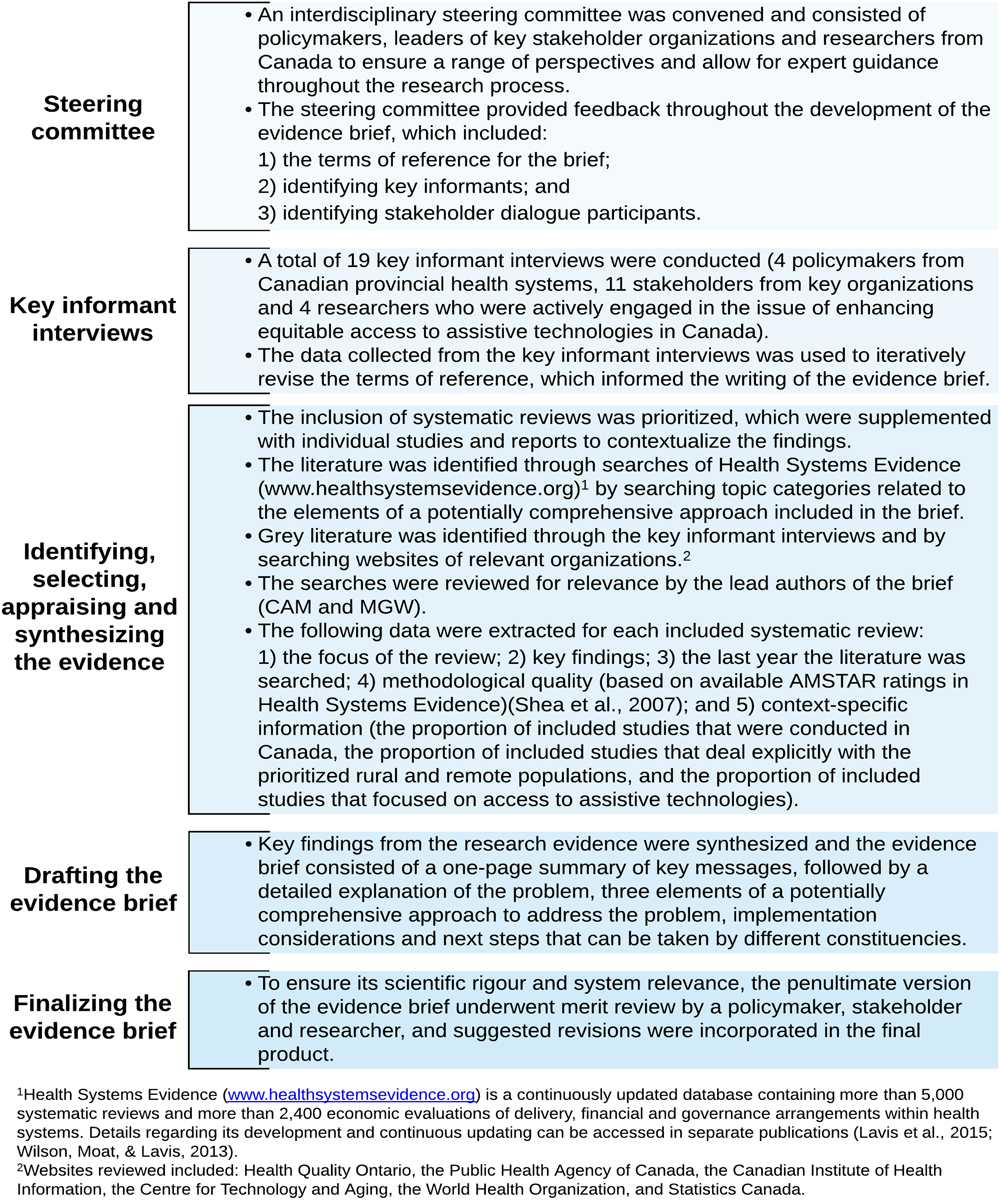

Using the McMaster Health Forum’s established methods, we prepared a citizen brief that mobilized the relevant research evidence about the problem and its causes, elements of a potentially comprehensive approach for addressing it, and key implementation considerations. The brief was informed by feedback from 19 key informants (i.e., policymakers, leaders of key stakeholder organizations, and researchers) and consultation with the steering committee (Mattison, Waddell et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017). Similarly, each dialogue participant was sent an evidence brief prior to the event, which was a more detailed version of the citizen brief and also included key findings from the three citizen panels (Mattison, Wilson, et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017). The McMaster Health Forum’s formative and summative evaluations of the citizen panels and stakeholder dialogues it convened found that participants consistently rated the briefs, panels, and dialogues very highly in terms of how they achieve their purposes. Figure 1 gives an overview of the methods used to prepare the evidence brief.

Figure 1: Overview of the stages of evidence brief development (adapted from Denburg et al., Reference Denburg, Wilson, Johnson, Kutluk, Torode and Gupta2017; Wilson, Lavis, Moat, & Guta, Reference Wilson, Lavis, Moat and Guta2016)

Citizen Panels

Citizen panels provide the opportunity for citizens to make informed judgments about enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies. Specifically, we used a deliberative approach to uncover citizens’ unique understandings of the issue in Canada and to spark insights about viable solutions that are aligned with their values and preferences (McMaster Health Forum, 2019). We convened three citizen panels in spring 2017 in three Canadian provinces (Ontario, Alberta, and New Brunswick).

We identified a purposive sample of participants for each of the panels from AskingCanadians (http://www.delvinia.com/companies/askingcanadians/), which is a full-service data collection firm with an online research community of approximately 600,000 Canadians. The pool of panellists maintained by the company is demographically representative of the Canadian population and continuously monitored against Statistics Canada population and demography data to gauge statistical representation. Their database provides more than 50 personal attributes of panellists (such as gender, age, level of education, employment, languages, etc.), tens of medical condition attributes, digital and social media behaviours, and other dimensions that cannot be found through mail list providers (such as Canada Post). The criteria for recruitment for this project specified that each panel should include a mix of people with and without lived experiences (including identified need for assistive technologies) and be balanced in terms of gender, age, socioeconomic status, ethnocultural background, and individuals living in different regions of the province in which the panel is hosted (e.g., urban, rural, and northern) (Table 1). The panels excluded (a) health care professionals or employees of health care organizations; (b) elected officials; (c) individuals working for market research, advertising, public media or public relations firms; and (d) individuals who had taken part in two or more previous citizen panels convened by our team. A thematic analysis of deliberations arising from the citizen panels was conducted by study-team members (CAM, MGW, and KW) based on notes from the facilitator, secretariat, and audio recordings from each panel.

Table 1: Citizen panel characteristics

Stakeholder Dialogue

Stakeholder dialogues are an approach to collective problem-solving and consist of off-the-record deliberations with policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers (Boyko, Lavis, Abelson, Dobbins, & Carter, Reference Boyko, Lavis, Abelson, Dobbins and Carter2012). The steering committee identified dialogue participants on the basis of their ability to bring unique insights about enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada, as well as on their ability to champion change following the dialogue. The dialogue was convened on June 8, 2017 in Hamilton, Ontario. The facilitator (MGW) engaged participants in deliberations about the problem, three elements of a potentially comprehensive approach to addressing the problem, implementation considerations, and next steps that could be taken by different constituencies. Similar to the citizen panels, study-team members (CAM, MGW, and KW) used notes from the facilitator and secretariat to develop a thematic analysis of the deliberations.

Results

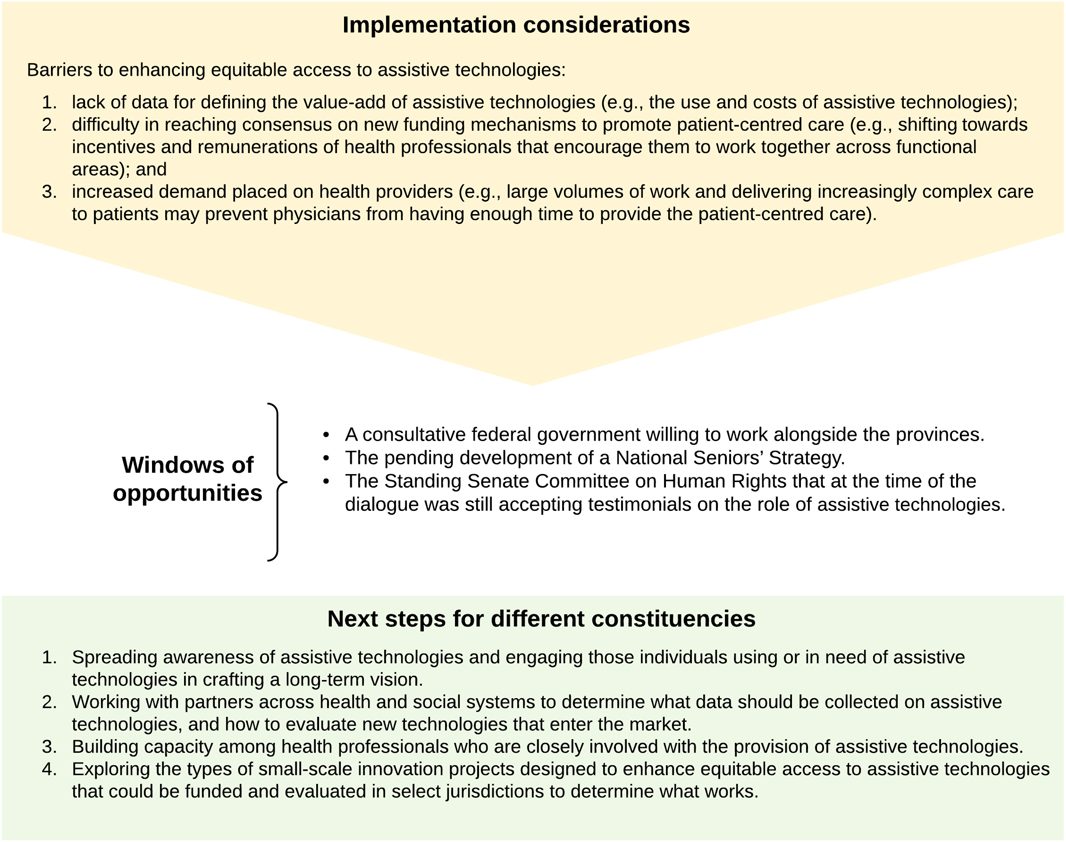

Following is our summary of the main findings from the evidence brief and the major themes that emerged from the deliberations in the citizen panels and the stakeholder dialogue. Additional information is available on the McMaster Health Forum’s website (www.mcmasterhealthforum.org), which includes the full citizen and evidence briefs as well as panel and dialogue summaries (Mattison, Waddell, Wang, et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017; Mattison, Waddell, & Wilson, Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017; Mattison, Wilson, et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017; Waddell, Wilson, & Mattison, Reference Waddell, Wilson and Mattison2017). A high-level synthesis of the main themes are (a) the factors contributing to the problem identified in the evidence brief (Table 2); (b) additional factors contributing to the problem identified by citizen panel and stakeholder dialogue participants (Table 3); (c) key findings of the three elements of an approach to address the problem (Table 4); and (d) a summary of the implementation considerations, windows of opportunities, and next steps prioritized by dialogue participants (Figure 2).

Table 2: Summary of the main factors contributing to the problem outlined in the evidence brief

Table 3: Summary of additional factors contributing to the problem identified by citizen panel and stakeholder dialogue participants

Table 4: Summary of key findings related to three elements of an approach to address the problem

Note. * Medicines are used as an analogue to assistive technologies as they provide some indication of how individuals may use and demand products as a result of changes to financial mechanisms.

Figure 2: Summary of the implementation considerations, windows of opportunities and next steps involved in enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies prioritized by dialogue participants (Waddell et al., Reference Waddell, Wilson and Mattison2017)

Main Findings from the Evidence Brief

The main factors contributing to the challenges of enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada included (a) the many different definitions for assistive technologies that can lead to confusion about what they are and what is covered by government-funded programs; (b) the increasing need for assistive technologies; (c) inconsistent access to assistive technologies, which in some cases results in unmet needs; and (d) system-level factors that can complicate access to assistive technologies.

We could select from many approaches to choose a starting point for deliberations about an approach for enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada. To promote discussion about the pros and cons of potentially viable approaches, our evidence brief outlined three elements of a potentially comprehensive approach, which we developed and refined through consultation with the Steering Committee and key informants. The elements focused on activities related to (a) informing citizens, caregivers, and health care providers to help them make decisions about which assistive technologies they need and how to access them; (b) helping citizens get the most out of government-funded programs; and (c) supporting citizens to access needed assistive technologies not covered by government-funded programs.

A range of barriers may hinder implementation of the three elements, each of which needs to be factored into any decision about whether and how to pursue any given element. The main barriers that we identified in the brief were as follows: (a) The expectations of individuals in need of assistive technologies and their caregivers in terms of what can be publicly financed may not align with the realities of government budgets; (b) the increased demands placed on health care providers in terms of supporting informed decision-making and system navigation (including determining program eligibility and coverage) may not be feasible given existing time constraints; and (c) streamlining government approaches for regulatory approval processes for assistive technologies requires significant involvement of and collaboration between federal- and provincial-level policymakers, which is often hard to achieve.

At the individual level, some patients, caregivers, and others may be unaware of existing or new supports available to them. At the care provider level, health care providers may not be equipped to be responsible for keeping up with which assistive technologies are eligible for public funding as well as who is eligible to receive them. At the organizational level, organizations that offer assistive technologies programs may find such programs difficult to coordinate; they may also lack the infrastructure needed to support system navigation and a streamlined approach to regulatory approval processes. At the system level, continuous innovation means that technologies are rapidly changing, and the criteria for identifying publicly financed technologies will need to be flexible and also require significant collaboration from a broad range of stakeholders (e.g., federal and provincial government ministries, private insurers, non-profit and charitable organizations, and manufacturers/vendors/distributors), which may be challenging. Potential windows of opportunity that could be capitalized upon include (a) demographic shifts in the population necessitating system change; (b) the alignment of provincial and territorial health-system policy priorities and strategic goals of the federal government on enhancing access to the home and community care sector; and (c) resource constraints, which can often support the creation of innovative approaches to health care problems.

Main Findings from the Citizen Panels

A total of 37 ethnoculturally and socio-economically diverse citizens participated in three panels (n = 15 Edmonton, n = 12 Moncton, n = 10 Hamilton) (Table 1). Panellists were from Alberta, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. Of those who had lived experience, individuals had participated in a variety of programs and services offering assistive technologies, including federal programs (e.g., Veterans Affairs Canada), publicly funded provincial programs, municipal programs, charitable organizations, private insurance, and employment-based benefits.

During the problem deliberation process, citizens were asked to share what they perceived to be the main challenges related to accessing assistive technologies or the services and supports needed to allow their use, on the basis of their experiences or those of a family member or someone to whom they provide care. Panellists identified the following seven additional factors related to enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada: (a) assistive technologies do not seem to be fairly allocated; (b) access to assistive technologies is complicated and often not focused on needs of the individual; (c) many face challenges in paying for needed assistive technologies and/or engaging with the private sector to identify and purchase what they need; (d) there is a lack of an integrated approach to the delivery of assistive technologies as part of larger care pathways and packages of care; (e) stigma associated with needing an assistive technology; (f) caregiver burden and challenges in getting appropriate supports; and (g) the lack of integration of assistive technologies into infrastructure (Tables 2 and 3) (Mattison, Waddell, & Wilson, Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017).

During the deliberations about the elements of an approach to address the problem of access, panellists identified eight components that they viewed as being important to underpin any future actions (Table 4) (Mattison, Waddell, & Wilson, Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017), as follows:

(1) empowered patients and caregivers who can make evidence-informed decisions through access to reliable information about programs and services offering assistive technologies;

(2) collaboration among patients, providers, and organizations within the health system and other sectors to ensure more coordinated access to needed assistive technologies (and to care more generally);

(3) trusting relationships between patients and their primary-care providers;

(4) equity and fairness in access to assistive technologies;

(5) manageable per capita costs for the system (as an outcome to prioritize);

(6) a focus on excellent health outcomes through prevention of additional health issues;

(7) flexibility and adaptability of services; and

(8) accountability to ensure that pricing of assistive technologies is kept affordable.

When discussing the potential barriers and facilitators to moving forward, panellists identified collaboration between the health system and other sectors as a challenge, yet also as being central to supporting streamlined access to programs and services offering assistive technologies across Canada. Nonetheless, panellists thought there was an opportunity for coordination and collaboration given the potential for cost savings to the health system through greater efficiency. Within the health system and delivery of health care services, panellists identified having occupational therapists work within primary-care teams as key to supporting system navigation.

Main Findings from the Stakeholder Dialogue

The dialogue convened 22 participants, which included six policymakers, two managers of community-based organizations, one member of a health care professional organization, three representatives from citizen groups, seven individuals from stakeholder organizations, and three researchers. Twenty-one of the participants were from Canada; one of the researchers was from another country but with expertise in the Canadian policy context. Of those from Canada, 13 brought a national perspective to the issue. This included two federal policymakers and 11 representatives of national stakeholder organizations (e.g., community-based organizations, professional associations, patient groups, and/or groups with a direct interest in the topic). The remaining eight participants were from British Columbia (n = 2), Alberta (n = 1), Ontario (n = 4), and Nova Scotia (n = 1), which included three policymakers, two from stakeholder organizations and two researchers (who, although from universities based in a specific province, also brought a broader national and international perspective to bear on the issue).

During the deliberation about the problem of access to assistive technologies, participants agreed with the features of the problem outlined in the evidence brief and identified four additional challenges: (a) a small number of root causes (e.g., lack of consistent definition of assistive technologies, client-focused policies, long-term policy goals, and data that can be used to identify use and cost of assistive technologies) that drive many of the challenges that individuals face in accessing assistive technologies; (b) complex patient journeys not often being accommodated in the current system; (c) financial challenges that are a critical barrier to achieving equitable access to assistive technologies; and (d) difficulty in achieving innovation and ensuring that high-quality products come to market. Table 3 provides the key messages, with examples, related to the problem identified by dialogue participants.

Participants collectively agreed that there is a need to focus on a policy framework that includes guidance for both short- and long-term change; Table 4 presents a summary of the main findings from systematic reviews related to the three elements of a potentially comprehensive approach to addressing the problem, along with key messages from the deliberations about each of these elements. Dialogue participants identified the following principles to underpin such a policy framework:

(1) Using a client-driven approach (i.e., engaging those affected by the issues in the change process and client centredness as a principle in enhancing equity);

(2) Fostering agreement on a definition of assistive technologies and/or bill of rights for those with disability;

(3) Ensuring universal access for technologies that support basic and instrumental activities of daily living (and thereby helping people lead independent lives without costly intervention from the health sector);

(4) Ensuring a simplified approach to accessing assistive technologies coupled with the flexibility needed to address an individual’s unique needs;

(5) Moving beyond a medical model to either a social or rights-based model (which was seen as helping to address many issues, including reducing assistive technology prices and adopting a holistic needs assessment approach);

(6) Fostering national leadership related to assistive technologies, as well as partnerships with industry to achieve common goals; and

(7) Fostering innovation not only for new technologies, but also for policy approaches that could be used to enhance equitable access (which could involve drawing on lessons learned from similar areas of policy such as prescription drugs, but with the caveats that not all examples will be applicable and that there is potential risk of continuing in a medical model depending on the analogy used).

In considering how to move forward with the elements and a long-term policy framework, participants identified several implementation considerations (see Figure 2). This included the identification of key barriers to implementation that must be overcome. These include (a) the lack of data and evidence for crafting a compelling narrative that is needed to politically prioritize efforts to enhance equitable access to assistive technologies and ultimately spark change; (b) difficulty in reaching consensus on new funding mechanisms to promote patient-centred care; and (c) the increased demand placed on health care providers (e.g., from large volumes of work and delivering increasingly complex care to patients) which may limit their time to provide the patient-centred care that is needed. Participants also identified several opportunities for moving the policy agenda forward, which included a consultative federal government willing to work alongside the provinces, the pending development of a National Seniors’ Strategy, and a senate committee on robotics, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing technologies that at the time of the dialogue was still accepting input.

Building on this, participants identified important next steps that they (either individually or collectively) thought were needed (see Figure 2). These included (a) spreading awareness of assistive technologies and engaging those individuals using or in need of assistive technologies in crafting a long-term vision; (b) working with partners across health and social systems to determine what data should be collected on assistive technologies, and how to evaluate new technologies that enter the market; (c) building capacity among health professionals who are closely involved with the provision of assistive technologies; and (d) exploring the types of small-scale innovation projects designed to enhance equitable access to assistive technologies that could be funded and evaluated in select jurisdictions to determine what works.

Discussion

Principal Findings

To enhance equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada, our findings point to a need to foster buy-in from policymakers, stakeholders, and researchers across the country. In considering the full array of elements, there was a general agreement that a focus on both short- (incremental) and long-term (aspirational) change is needed. Participants noted that despite the many changes they wanted to make as to how individuals access and use assistive technologies, they understood that these changes would take time, and that there was a need to make small improvements to the system in its current form. Participants highlighted incremental changes across all three elements that should be pursued, as Table 4 illustrates. In element 1, this included adopting a common language, improving service navigation and enhancing access to individualized assessments and solutions. For elements 2 and 3, participants focused on the need to better align government programs with the needs of those requiring assistive technologies, as well as to coordinate public- and private-insurance coverage to minimize gaps.

Throughout the deliberations, participants also emphasized that to move forward with any of the proposed solutions, there is a need for an organization or a close network of groups to “own” the area of assistive technologies. There was, however, some disagreement about whether this should be taken up by an existing organization or whether the development of a new agency that is able to straddle the medical-social divide might be a better fit.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of our approach was the use of best-available research evidence combined with citizens’ values and preferences to inform the evidence brief used to stimulate deliberations in the stakeholder dialogue. We considered systematic reviews along with an appraisal of their methodological quality in order to understand what is known about the elements that might contribute to addressing the problem of access. We integrated findings from the thematic analysis of the citizen panels into the evidence brief and informed the deliberation of the problem as well as the individual elements in the stakeholder dialogue. One main limitation of our approach is that, potentially, not all stakeholders were represented at the dialogue. However, we were able to ensure geographical representation with participants who brought a national perspective and from seven provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island). In addition, the Steering Committee ensured representation from the range of key stakeholders involved in the provision of assistive technologies at both federal and provincial levels and across organizations. Similarly, within the citizen panels there was also a potential limitation related to representation. The three panels were held in locations to draw from a wide range of citizens across Canada; however, no panel was conducted in French. Although the Moncton panel was conducted in English, the facilitator also spoke French and many of the participants were Francophone.

Implications for Policy and Practice

As we highlighted in the introduction, priorities in provincial and territorial health systems in Canada are focused on expanding the home and community care sector and supporting older adults at home to live at home as long as possible. However, programs that provide access to assistive technologies, which can enhance care and independence at home, vary greatly, and the approach to delivery is highly fragmented. Enhancing equitable access to assistive technologies in Canada therefore provides an opportunity to address important policy priorities and aligns with the United Nations’ Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, inasmuch as the use of assistive technologies spans health and social services sectors, care settings, and health conditions. Equitable access to assistive technologies is a key resource that, along with environmental design (universal), has the potential to improve citizens’ abilities.

The deliberations highlighted the need to develop a list of essential technologies for which those in need could receive coverage. Participants cited pharmaceutical advances in Canada as an example and discussed the possibility of creating a pan-Canadian alliance for assistive technologies to mirror the pan-Canadian pharmaceutical alliance, which could support collective purchasing power and more efficient procurement systems. Another feasible opportunity for policy development, identified by participants, was the integration of environmental design (universal) and considerations for those who may need assistive technologies when crafting public policy.

Implications for Future Research

In keeping with the aforementioned implications for policy, future research is needed to identify and develop the list of essential assistive technologies for public financing in Canadian health systems. As part of the evidence brief we prepared, we mapped the 50 priority assistive technologies identified by the World Health Organization’s Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology (GATE) initiative according to those that are fully or partially publicly financed by the federal government or provincial and territorial governments in Canada (World Health Organization, 2017). None of the 50 priority assistive technologies were available across all federal, provincial, and territorial programs, and several did not receive any public funding (e.g., time management products, portable travel aids, adaptive tricycles, and talking/touch-enabled watches) (Mattison, Wilson, et al., Reference Mattison, Waddell, Wang and Wilson2017; Schreiber, Wang, Durocher, & Wilson, Reference Schreiber, Wang, Durocher and Wilson2017). Moreover, only a few of the items on the list are designed to address cognitive or mental health concerns, even though cognitive changes (e.g., related to dementia) or mental health concerns (e.g., depression, social isolation, and loneliness) often occur as people age. Given this identified gap, there is a need for future research to create a list of essential assistive technologies that support basic independence and instrumental activities of daily living.

Other areas for future research that we identified in this project include (a) identification of the needed outcomes to support processes for the provision of assistive technologies (e.g., is an individualized model economically viable in terms of decreased waste, improved satisfaction, and improved quality of community participation?); (b) identification of the core indicators for improved system navigation; and (c) identification of the outcomes of improved system navigation in terms of quality of care and system performance.