INTRODUCTION

Organized stroke care results in reduced death and disability, but it is very complex. 1 There is abundant literature regarding the quality of stroke care within an individual setting or transitions between two sectors (e.g., acute to inpatient rehabilitation).Reference Gassaway, Horn, DeJong, Smout, Clark and James 2 - Reference Smith, Hassan, Fang, Selchen, Kapral and Saposnik 12 However, few studies have tracked stroke survivors across the entire continuum to understand the quality of care they received and their outcomes.Reference Coleman and Boult 13 - Reference Jia, Zheng, Reker, Cowper, Wu, Vogel and Young 15 This is a significant gap in our knowledge, as stroke patients take many variable paths or trajectories through the healthcare system. The Canadian Stroke Strategy has identified a Model for Transitions of Stroke Care and corresponding best practices for each sector, including: acute care, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, stroke secondary prevention clinics and primary care follow-up.Reference Coutts, Wein, Lindsay, Buck, Cote and Ellis 16 However, the proportion of stroke patients following the various trajectories and the quality of care are not known.

The reason for this lack of evaluation may be that very few health systems have the capacity to follow patients across the entire continuum of stroke care.Reference Smith, Hassan, Fang, Selchen, Kapral and Saposnik 12 , Reference Kolominsky-Rabas, Sarti, Heuschmann, Graf, Siemonsen and Neundoerfer 17 - Reference Wenger and Young 20 There is a dearth of studies that provide real-world knowledge of the care pathways for stroke patients based on comprehensive observational data to highlight where to focus quality improvement and stroke system planning.

The objectives of our study, therefore, were: (1) to characterize the first-year care trajectories and outcomes for first-ever acute stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) patients; (2) to describe the patient demographic factors (i.e., age, sex and stroke severity) associated with each trajectory; (3) to measure adherence to available best practices guidelines (i.e., appropriate diagnostic testing, access to specialists and prescribing stroke-prevention medications); and (4) to identify the priority areas of the stroke system upon which to focus quality-improvement activities.

METHODS

Data Sources and Cohort Creation

The Ontario Stroke Registry (OSR) (formerly known as the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network, or RCSN) performs a population-based biennial audit of the patients seen at all acute care institutions in Ontario. The 2012/13 Ontario Stroke Audit (OSA) is a random sample of patients 18 years of age and older discharged from the emergency department (ED) or from an inpatient stay between 1 April 2012 and 31 March 2013, with a main problem/most responsible diagnosis of stroke or TIA among hospitals seeing at least 30 strokes/TIAs per year. If there was more than one stroke/TIA during the sampling period, only the first stroke/TIA event was included.Reference Hall, Khan, O’Callaghan, Cullen, Levi and Wu 21 Results were weighted using the reciprocal of the probability that the chart was selected to provide for population estimates.Reference Hall, Khan, O’Callaghan, Cullen, Levi and Wu 21

Chart abstraction was performed by trained research personnel, and if chart review confirmed a diagnosis of stroke or TIA, the event was included in the OSA. The OSA collects information on stroke type and severity, presenting symptoms and co-morbid conditions, and validation by duplicate chart abstraction has shown excellent agreement for key variables, including age, sex, stroke type and admission to hospital.Reference Kapral, Silver, Richards, Lindsay, Fang and Shi 22

The OSR is housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), where it is linked to population-based administrative databases using unique encoded patient identifiers. Using an encrypted health card number, we excluded OSA patients who had had a stroke/TIA emergency department visit or hospitalization in the three years prior to the 2012/13 stroke event to identify first-ever stroke patients, leaving 12,362 patients to assign a trajectory. All trajectories began with an admission to the ED at 100 acute hospitals. A trajectory was classified by the first and/or second transition after ED care (e.g., home, home with home care, inpatient rehabilitation, complex continuing care or long-term care) using a unique encrypted health card number linked to several administrative databases and analyzed at the ICES (see supplementary material, Appendix 1).

Data Analyses

Results were weighted using the reciprocal of the probability that the audited chart was selected to provide for population estimates.21 This resulted in a cohort of 18,871 first ever stroke/TIA patients. Adherence to best practices stroke care was calculated as the proportion of patients receiving best practices among all eligible patients in that trajectory expressed as a percentage. The acute phase process indicators calculated are included in the Ontario Stroke Network’s stroke report cardReference Hall, Khan, O’Callaghan, Cullen, Levi and Wu 23 and include: dysphagia screening, neuro- and carotid imaging, thrombolytic therapy (tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]), admission to a stroke unit and referral to a secondary prevention services. Post-acute best practices indicators were selected based on data availability in Ontario. We excluded patients who died during the follow-up for medication adherence only. Patients were followed for up to 365 days after the index event.

RESULTS

Predominant Trajectories of Stroke Care in Ontario

There are six predominant trajectories following a first-ever stroke/TIA in Ontario, and most (64.5%) involve hospitalization. Four of the six trajectories transition to the community after an acute event. The most common trajectory of care (26%) is transitioning to home from the ED (T1).

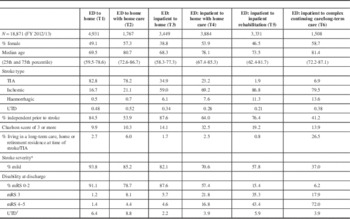

Patient Characteristics (see Table 1)

In the Table 1 most common trajectory (T1), most patients experience a TIA (82.8%), are younger (69.5 years), male (50.9%), have fewer co-morbidities (5.4% with a Charlson comorbidity index of 3 or more) and were living independently prior to the stroke (84.5%). In contrast, those transitioned to home care from the ED (T2) were over a decade older (median=80.7 years), more likely to be female (57.3%) and less independent (53.9%).

Table 1 Patient Characteristics in Six Stroke Care Trajectories

* Measured on the Canadian Neurological Scale 8 or higher.

mRS=modified Rankin score.

† Not enough information in the chart for abstractors to be able to calculate.

Trajectories with transitions directly to home following an acute stroke (T1 and T3) had patients similar in age (69.5 vs. 68.3 years) and independence (84.5 vs. 87.6%), but were more likely males, with fewer comorbidities (5.4 vs. 11.0%, with a Charlson comorbidity index ≥3). However, T3 (admitted) patients had more severe strokes (93.8 vs. 82.1%, considered mild).

Patients in trajectories including home care (T2 and T4) were older, more likely female and had more co-morbidities, but admitted patients (T4) were more independent (64.0 vs. 53.9%) and experienced more severe strokes (70.6 vs. 85.2% mild) compared to those not admitted.

Trajectory five (transition to inpatient rehabilitation) had the second youngest stroke/TIA patients (median age=73.5 years). T5 also had the highest prevalence of patients who had been independent in terms of performing the activities of daily living prior to their stroke and after their discharge home without supports (T1 and T3) (76.4%), but they experienced more severe strokes (only 57.8%, mild strokes) compared to patients discharged home with or without supports and a high proportion of patients with a modified Rankin score >2 (84.6%) at the time of discharge from the acute hospital.

The least common trajectory (T6) involved direct transition to long-term care (LTC) or complex continuing care (CCC) facilities. In fact, 26.5% resided in an LTC-type residence prior to their index stroke/TIA. This group was the oldest (median age=81.4 years), had the highest proportion of women (58.7%) and had the lowest proportion of patients considered to be independent (41.2%). Less than half of T6 patients experienced a mild stroke (37.0%), and 93.8% had a discharge modified Rankin score >2.

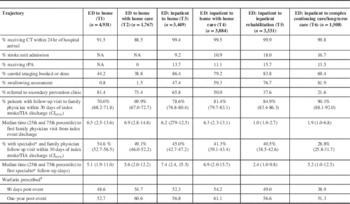

Adherence to Acute Stroke Care Best Practices

Trajectory five had the highest proportion of patients receiving best practices stroke care, with the exception of referrals to a secondary stroke prevention clinic and warfarin adherence (Table 2). This trajectory also had the highest prevalence of tPA delivery (15.6%). T4 had the lowest proportion receiving tPA despite having a greater proportion of ischemic stroke patients as compared to T3. Among the trajectories that included hospitalization, T3 (transition to home) had the lowest proportion of patients cared for on a stroke unit (9.2%) with swallowing assessed (47.4%) but had the highest percentage referred to a secondary stroke prevention clinic (65.8%) among patients admitted to hospital. Trajectory T6 (transition to CCC or LTC) had the second highest rate of patients treated on a stroke unit (16.7%). Patients discharged home (T3 and T4) had the lowest proportion of patients treated on a stroke unit.

Table 2 Adherence to Best Practices among Six Stroke Care Trajectories

CI 95%=95% confidence interval; CT=computed tomography; tPA=tissue plasminogen activator.

* Specialist was defined as neurologist, neurosurgeon, internist, cardiologist or physiatrist.

¥ Ischemic stroke/TIA patients with atrial fibrillation 65 years of age and older.

Trajectories without an inpatient stay (T1 and T2) had the lowest rates of brain and carotid artery imaging (44.2 and 38.8%) and the highest secondary prevention clinic referrals (81.4 and 73.4%, respectively) compared to trajectories with an inpatient stay for acute stroke management. These patients also had the lowest 30-day family physician visit rate (70.0 and 69.9%) of all the trajectories but the highest rate of seeing both a family physician and specialist (54.6 and 49.1%). Furthermore, the median time to see a specialist was shorter for trajectories without an inpatient stay compared to hospitalized patients transitioned to the community: 5.1 versus 7.4 days (T1 vs. T3) and 5.6 versus 6.9 days (T2 vs. T4). The median time to specialist visit was shortest for T5 (acute+inpatient rehabilitation) at 2.4 days, followed by T6 at 5.2 days. Trajectories T2 and T4 (transitions to home care) had the highest use of warfarin at three months and one year following the stroke/TIA: 54.7, 60.6% and 54.2, 61.1%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This is the first population-based study to characterize adherence to best practices by care trajectory following first-ever stroke/TIA. We have found six health system care trajectories that first-onset stroke patients in Ontario follow. Two of the six trajectories do not include an inpatient stay and are predominantly TIA patients at high risk for a stroke. Each trajectory is associated with significant variability in terms of patient characteristics and adherence to identified best practices.

Not surprisingly, patients managed in the ED only had less severe strokes and fewer co-morbidities. In contrast, those discharged to long-term care (T6) were older, less independent pre-stroke and more disabled. It was noteworthy that those going to rehabilitation (T5) were younger, raising the possibility of ageism inpatient rehabilitation admission policies. Long-term care (T6) is resource-intensive, and it is possible that the longitudinal cost of care could be reduced if more received rehabilitation. Overall, a small percentage of first-ever stroke/TIA patients transition directly to inpatient rehabilitation: 17.7% (T5). A 2009 analysis of stroke rehabilitation in Canada reported that inadequate access to resources that focus on rehabilitation has meant that admission to long-term care has remained largely unchanged.Reference Teasell, Meyer, Foley, Salter and Willems 10

Patients transitioning to home care services (T2, T4) or to long-term care (T6) were older, more likely female, less likely independent prior to their stroke and had experienced a more severe stroke. Women have strokes at an older age, innately live longer than men and are less likely to have male caregivers to support them. The results of our study bolster the literature which shows that those aged over 80 have worse overall outcomes, including higher mortality rates and longer lengths of stay, and are less commonly discharged to their pre-stroke location.Reference Saposnik, Fang, O’Donnell, Hachinski, Kapral and Hill 24 , Reference Bejot, Rouaud, Jacquin, Osseby, Durier and Manckoundia 25

In terms of quality of care, among patients receiving ED-only management (T1 and T2), less than 50% had carotid imaging, and 30% did not follow up with any physician within 30 days of the stroke/TIA. The median time to see a physician was six days. This suboptimal follow-up in T1 and T2 among those who had high rates of prescribed warfarin raises the concern that less frequent monitoring may contribute to the higher rates of ischemic stroke among atrial fibrillation patients newly prescribed warfarin.Reference Tung, Mamdani, Juurlink, Paterson, Kapral and Gomes 26

Among trajectories with an inpatient stay, less than 20% of patients received stroke unit care. Stroke units reduce death or institutionalization with the same magnitude of effect across all age groups.Reference Saposnik, Kapral, Coutts, Fang, Demchuk and Hill 27 In trajectories where post-acute stroke patients were transitioned to the community (T1-T4), screening rates for dysphagia were the lowest, but this may be due to their shorter length of stay compared to T5 and T6. A more concerning possibility is that clinicians take a nihilistic approach to older people with fewer referrals to inpatient rehabilitation, less use of preventive medication and less access to follow-up care (T6). T5 and T6 have the lowest one-year warfarin adherence rates, suggesting that the need to ensure secondary prevention is conveyed better in the discharge care plans.

Our study has several limitations worth commenting on. Not all Ontario acute care hospitals were included in the 2012/13 OSA; therefore, the analysis does not provide a picture of all acute stroke care episodes and may overestimate the adherence to best practices by excluding hospitals that see less than 30 stroke/TIA cases a year. Subarachnoid haemorrhage stroke patients were not included. However, given that this stroke type represents less than 10% of stroke patients, it is unlikely to have impacted our results. Adherence to secondary stroke prevention medications was obtained from the Ontario Drug Benefits (ODB) database, limiting quantification of adherence to patients over age 65 years at the time of the acute stroke/TIA. Adherence to antiplatelet medications was not calculated, as aspirin is not covered nor tracked by the ODB program. Finally, our results were obtained within the context of an organized system of stroke care and may not be generalizable to other settings.

This study is based on recent stroke care, and many indicators of best practice care may have improved in the meantime. In a more current report on stroke care in Ontario, stroke unit care and carotid imaging among stroke/TIA patients improved, and provided insights into trajectories where further improvement is needed.Reference Hall, Khan, Levi, Zhou, Lumsden, Martin and Morrison 28 During the period of our study, early supported discharge (ESD) was not available in the province of Ontario, and so it is not unexpected that transitions involving home care had a lower prevalence of many best practices that are part of ESD programs.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have identified six main trajectories following a first-ever stroke/TIA. Significant variability in age, severity of stroke, presence of co-morbidities, pre-morbid functioning and quality of care exists across these trajectories. Our population-based observational study provides estimates of adherence to several best practices useful for stroke system planning in Ontario as well as for other countries/regions with a formalized stroke system. Future analysis with this cohort will examine which trajectories and elements of care are associated with the best one-year outcomes.

We also identified four areas for improvement in stroke care:

-

1. Individuals discharged home directly from the ED where the majority are considered TIA patients and at high risk for stroke require more consistent access to diagnostic imaging and dysphagia screening.

-

2. Patients in trajectories that include admission to hospital should have increased access to stroke units.

-

3. A large percentage of patients transitioning to LTC could potentially benefit from inpatient rehabilitation.

-

4. Discharge planning should include organization of timely follow-up with a physician familiar with secondary stroke prevention, particularly among patients discharged directly from the ED.

ETHICS

This study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jen Levi for her assistance with manuscript preparation. Parts of this material were based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the CIHI. The Ontario Stroke Registry is funded by the CSN and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The ICES is supported by an operating grant from the MOHLTC. The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be attributed to any supporting or sponsoring agencies. No endorsement by the CSN, the ICES nor the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. We would also like to acknowledge support from the Health System Performance Research Network (grant no. 06034), supported by a grant from the MOHLTC.

Disclosures

Prosanta Mondal reports grants from the ICES and was supported by an operating grant from the MOHLTC during the conduct of this study.

Walter Wodchis has the following disclosure: University of Toronto, principal investigator; MOHLTC grant no. 06034.

Ruth Hall has the following disclosures: OSR (funded by the CSN and MOHLTC): evaluation specialist, salary; ICES, which is supported by an operating grant from the MOHLTC: adjunct scientist.

Jiming Fang has the following disclosure: ICES, which is supported by an operating grant from the MOHLTC: employee, salary.

Diana Sondergaard and Mark Bayley hereby state that they have nothing to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article (Appendix 1), please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.440