Case Report

A 79-year-old woman with osteoporosis, dyslipidemia, and 1 year of unexplained weight loss (less than 30 lb) was on her way to see her family physician. She had booked the appointment because she had been feeling generally unwell and fatigued for several weeks—her condition worsening in recent days. She collapsed in her residential driveway, and paramedics attended to her within 10 minutes. At the scene, she was pulseless with agonal-type respirations, and the paramedics initiated CPR. On arrival at the local emergency department, the patient had a Glasgow Coma Scale of 3 and vital signs were absent. In the hospital, the patient received continued standard resuscitative efforts, including chest compressions, four external cardiac defibrillation attempts, oxygen delivery via bag-valve-mask and boluses of epinephrine, calcium, and bicarbonate. Chest compressions resulted in rib fractures and an unusual swelling of the right neck. The patient never achieved return of spontaneous circulation, and the health care providers ceased resuscitation efforts after 25 minutes of standard total CPR protocol.

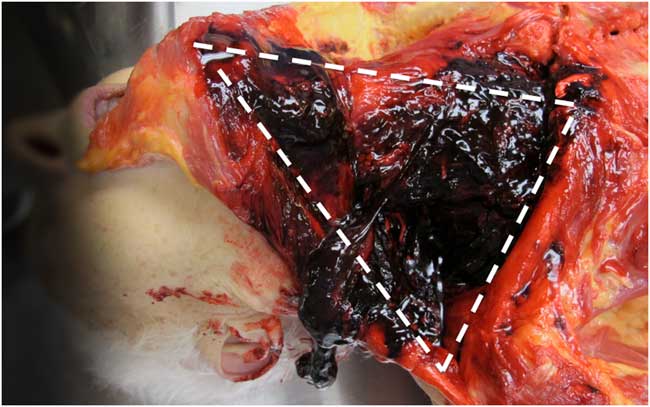

A postmortem examination was requested to determine the cause of death. On opening the thorax, extensive blood was present throughout the soft tissues of the right anterior thorax and neck (Figure 1). Several right anterior rib fractures were apparent, and the right hemithorax contained 1300 mL of sanguineous fluid. Mediastinal examination revealed a 1-cm tear of the anterior pericardium.

Figure 1 Extensive hemorrhage was observed within the tissues of the right neck (white triangle), mediastinum, and thorax.

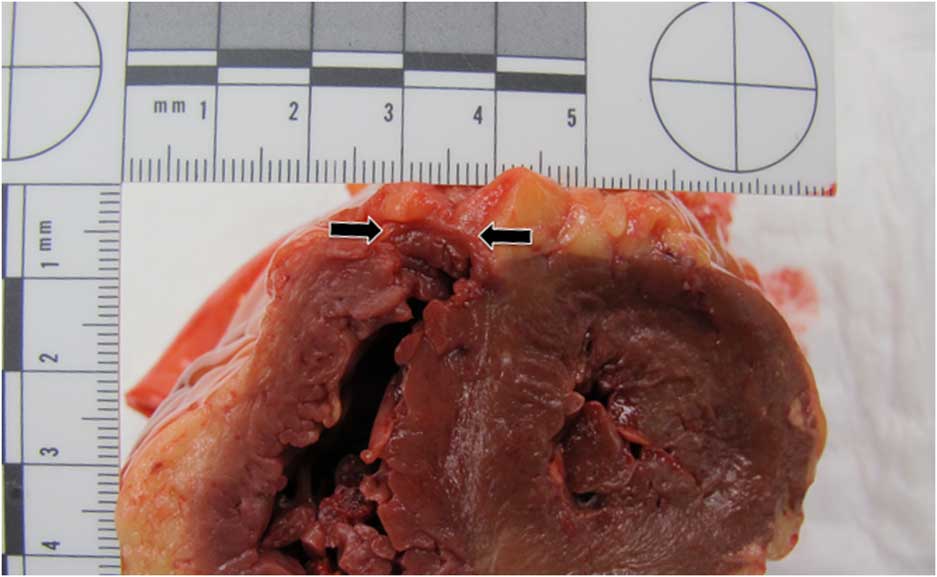

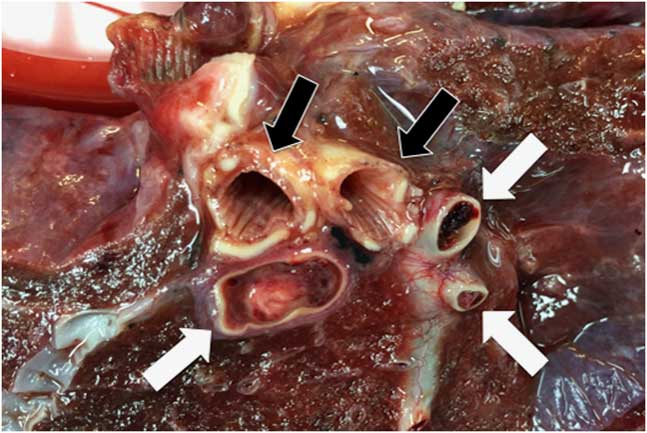

Additionally, the heart was remarkable for a 2-cm transmural tear of the anterior right ventricle (Figure 2). No evidence of predisposing disease contributing to cardiac rupture was evident grossly (e.g., dilated cardiomyopathy, ventricular hypertrophy) or microscopically (e.g., prior myocardial infarction, myocarditis), and no evidence of antemortem tissue damage was evident, suggesting a traumatic rupture during resuscitation. Examination of the lungs revealed extensive thromboemboli in both large and small pulmonary vessels (Figure 3). Histologically, these showed both acute and chronic features, including varying degrees of organization, granulation, fibrosis, and recanalization. The pulmonary vessels did not show evidence of arterial atherosclerosis or small vessel muscular hypertrophy, as can be seen in chronic pulmonary hypertension. No putative source of thrombus was identified on examination of the deep veins of the legs.

Figure 2 Presence of a transmural myocardial tear of the anterior right ventricle (located between black arrows).

Figure 3 Occlusive thrombi were present within the large pulmonary arteries (white arrows). The large airways (black arrows) were unremarkable.

In summary, the patient died from diffuse pulmonary emboli with traumatic rupture of the right ventricle secondary to chest compressions during CPR.

Discussion

Injuries secondary to the trauma of CPR-associated chest compressions are common. Estimates of the incidence of some type of resuscitation injury ranges from 21%-65%,Reference Hashimoto, Moriya and Furumiya 1 and up to 97.4%.Reference Lederer, Mair and Rabl 2 Although these injuries infrequently have a significant effect on the patient’s outcome,Reference Buschmann and Tsokos 3 clinicians should be mindful that anterior-posterior chest radiographs underestimate true fracture frequency.Reference Lederer, Mair and Rabl 2 Hashimoto et al.Reference Hashimoto, Moriya and Furumiya 1 reported that CPR results in an average of 7.1 broken ribs, with ribs 3-5 being the most frequently involved. Rib injuries occur with greater frequency in women and with increased age.Reference Buschmann and Tsokos 3 Other CPR-associated injuries that occur with notable frequency (>20% of autopsy cases) include chest abrasion/contusion, defibrillator burns, sternal fractures, upper airway injuries, and pulmonary edema.Reference Krischer, Fine and Davis 4

It is recognized that different methods of CPR result in different risks of thoracic wall trauma. Miller et al.Reference Miller, Rosati and Suffredini 5 compared standard CPR methodology (chest compressions using the hands only) with CPR, using active compression devices (ACDs) employing either suction cup, automated piston, or load-distributing band technologies. Their findings showed that sternal and rib fracture rates, respectively, were 8.5% and 25.9% in manual compression, 80.6% and 47.2% for suction cup ACD, and 16.9% and 25.4% for piston ACD. Use of load-distributing band ACD resulted in sternal fractures in 13.5% of cases (rib fractures were not reported for load-distributing band ACD). Hence, standard CPR appears to be less traumatic to the chest wall than ACD technologies.

Less frequent injuries resulting from CPR include liver lacerations (0.6%-2.1%), gastric rupture (<1%) and splenic lesions (<1%).Reference Buschmann and Tsokos 3 A rare complication of CPR is trauma to the heart and associated structures (e.g., great vessels and pericardium). Krischer et al.Reference Krischer, Fine and Davis 4 reviewed 700 autopsy cases involving CPR and found vena cava trauma in 0.9% of cases and myocardial contusion in 1.3% of cases. In only a single case (0.1% overall) was there incidence of myocardial laceration. Similarly, in a review of 2659 autopsy cases, only three incidences of right ventricular rupture secondary to CPR were identified.Reference Bodily and Fischer 6 Last, two comprehensive meta-analyses of CPR-associated injuries found myocardial rupture in only 5 of 818 (0.6%)Reference Miller, Rosati and Suffredini 5 and <1% of cases.Reference Hoke and Chamberlain 7

Resuscitation-associated myocardial injury has been observed in a number of clinical settings, including cases of acute myocardial infarction,Reference Natsuaki, Yamasaki and Morishige 8 broken ribs,Reference Bodily and Fischer 6 , Reference Sokolove, Willis-Shore and Panacek 9 multiple large pulmonary emboli,Reference Baldwin and Edwards 10 and recent lung and pericardial surgery.Reference Kempen and Allgood 11 Regardless of the mechanism of injury, myocardial injury carries a significant likelihood of mortality given the rapid progression to fatal exsanguination,Reference Martin, Flynn and Rowlands 12 but early recognition of the injury with prompt repair offers a chance of survival.Reference Natsuaki, Yamasaki and Morishige 8 , Reference Martin, Flynn and Rowlands 12

In our case, similar to the description by Baldwin and Edwards,Reference Baldwin and Edwards 10 pulmonary emboli would have created an elevated right ventricular pressure, which is postulated to increase the likelihood of rupture. Additionally, although the fractured ribs were not adjacent to the heart at the time of postmortem examination, given the concurrent pericardial tear, it is possible that the ribs were displaced during chest compressions, contributing to cardiac rupture.

In summary, acute care clinicians should keep in mind that standard CPR is a traumatic intervention, and all successful resuscitations should be followed by a thorough evaluation for post-CPR injuries that may require treatment. Rib fractures are the most common injury, and women of increased age, especially with osteopenia/osteoporosis, are in the highest risk demographic.Reference Buschmann and Tsokos 3 Although uncommon, injuries to the respiratory tract, gastroesophageal tract, upper abdominal organs, and cardiovascular system can all result from CPR and may present life-threatening injury in the post-resuscitation period. An assessment for iatrogenic myocardial injury in patients receiving CPR for diffuse pulmonary emboli should be considered.

Competing interests: None declared.