Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref.

Hall, Andrew K.

Woods, Rob

and

Frank, Jason R.

2019.

Changing the culture of residency training through faculty development – ERRATUM.

CJEM,

Vol. 21,

Issue. 6,

Chorley, Alexander

Welsher, Arthur

Pardhan, Alim

Chan, Teresa M.

and

Chen, Esther

2021.

Faculty‐lead Opinions on Workplace‐based Methods for Graduated Managerial Teaching (FLOW MGMT): A National Cross‐sectional Survey of Canadian Emergency Medicine Lead Educators.

AEM Education and Training,

Vol. 5,

Issue. 1,

p.

19.

Robinson, Trevor J. G.

Wagner, Natalie

Szulewski, Adam

Dudek, Nancy

Cheung, Warren J.

and

Hall, Andrew K.

2021.

Exploring the use of rating scales with entrustment anchors in workplace‐based assessment.

Medical Education,

Vol. 55,

Issue. 9,

p.

1047.

Van Melle, Elaine

Hall, Andrew K.

Schumacher, Daniel J.

Kinnear, Benjamin

Gruppen, Larry

Thoma, Brent

Caretta-Weyer, Holly

Cooke, Lara J.

and

Frank, Jason R.

2021.

Capturing outcomes of competency-based medical education: The call and the challenge.

Medical Teacher,

Vol. 43,

Issue. 7,

p.

794.

Cheung, Warren J.

Hall, Andrew K.

Skutovich, Alexandra

Brzezina, Stacey

Dalseg, Timothy R.

Oswald, Anna

Cooke, Lara J.

Van Melle, Elaine

Hamstra, Stanley J.

and

Frank, Jason R.

2022.

Ready, set, go! Evaluating readiness to implement competency-based medical education.

Medical Teacher,

Vol. 44,

Issue. 8,

p.

886.

Paterson, Quinten S.

Alrimawi, Hussein

Sample, Spencer

Bouwsema, Melissa

Anjum, Omar

Vincent, Maggie

Cheung, Warren J.

Hall, Andrew

Woods, Rob

Martin, Lynsey J.

and

Chan, Teresa

2023.

Examining enablers and barriers to entrustable professional activity acquisition using the theoretical domains framework: A qualitative framework analysis study.

AEM Education and Training,

Vol. 7,

Issue. 2,

Cadieux, Magalie

McKinley, Sophia K.

Odewade, Niyi

Riva-Cambrin, Jay

and

Phitayakorn, Roy

2023.

Neurosurgeons’ Perspectives on Vascular Entrustable Professional Activities.

Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques,

Vol. 50,

Issue. 2,

p.

287.

Yilmaz, Yusuf

Chan, Ming-Ka

Richardson, Denyse

Atkinson, Adelle

Bassilious, Ereny

Snell, Linda

and

Chan, Teresa M.

2023.

Defining new roles and competencies for administrative staff and faculty in the age of competency-based medical education.

Medical Teacher,

Vol. 45,

Issue. 4,

p.

395.

Hall, Andrew K.

Oswald, Anna

Frank, Jason R.

Dalseg, Tim

Cheung, Warren J.

Cooke, Lara

Gorman, Lisa

Brzezina, Stacey

Selvaratnam, Sinthiya

Wagner, Natalie

Hamstra, Stanley J.

and

Van Melle, Elaine

2024.

Evaluating Competence by Design as a Large System Change Initiative: Readiness, Fidelity, and Outcomes.

Perspectives on Medical Education,

Vol. 13,

Issue. 1,

p.

95.

On July 1, 2018, all Royal College Emergency Medicine (EM) postgraduate training programs implemented competence by design.1 This represented the largest change in postgraduate training that those in practice have seen during their careers. While the goals of this change are many, the primary purpose is to better meet the needs of the patients we care for.Reference Holmboe, Sherbino and Englander2 As an innovation, competence by design is about implementing all the best practices and principles of medical education that we have learned about over the past few decades to create Residency 2.0. This transition presents an exciting opportunity for comprehensive faculty development, with a critical focus on the delivery of high-quality coaching feedback on the front-line to promote cultural change.

Much like a software upgrade, Residency 2.0 has undoubtedly caused initial disruption. Competence by design represents a significant curricular change, focusing on the sequenced progression of trainee competencies and outcomes, learning and teaching tailored to competencies, and programmatic assessment,Reference Van Melle, Frank and Holmboe3 all while promoting a culture of critical self-reflection, continuous assessment, and lifelong learning.Reference Ferguson, Caverzagie and Nousiainen4 On the back end, program directors and administrators have been working tirelessly to revamp curricula and rotations, taking theory, and implementing it in practice. Simultaneously, front-line faculty around the country are navigating novel electronic assessment tools, rating scales, and training activities, as well as a renewed demand for focused feedback, teaching, and coaching. For front-line faculty, this requires an increase in the direct observation of trainees and a focus on the provision of high-quality, competency-focused coaching feedback.1 How can we best prepare and support our faculty in this major transition? What do our faculty both want and need?

In this issue of CJEM, Chan et al.Reference Chan5 help us to answer these questions, by describing Canadian EM physician and resident perceptions about competence by design, attitudes toward implementation, and perceived faculty development needs. The authors specifically identify priorities for faculty development relating to feedback delivery, completing workplace-based assessments and making resident promotion decisions. It is clear that the renewed investment in postgraduate training has placed the microscope again on the interactions between residents and faculty on both the front-line and the backroom. This has stimulated faculty to ask questions again like, “how can I give better feedback?,” “how can I be critical of a trainee while not hurting their feelings?,” and “how do I decide if I can trust a trainee?” This rejuvenated interest can be, and needs to be, harnessed by all EM training programs to drive this culture shift forward through faculty development.

Faculty development refers to all activities whose purpose is to improve knowledge, skills and behaviours as educators, leaders, and scholars.Reference Steinert, Mann and Anderson6 While formal structured group workshops tend to be the most commonly utilized activities, there are a multitude of potential approaches that exist along a continuum of formality and may be focused on an individual or a group.Reference Steinert7 In general, features of faculty development that make it more likely to affect change include relevant content, practice and application, feedback and reflection, a longitudinal program design, and institutional support.Reference Steinert, Mann and Anderson6 All these features should be considered when engaging in efforts relating to the implementation of competence by design.

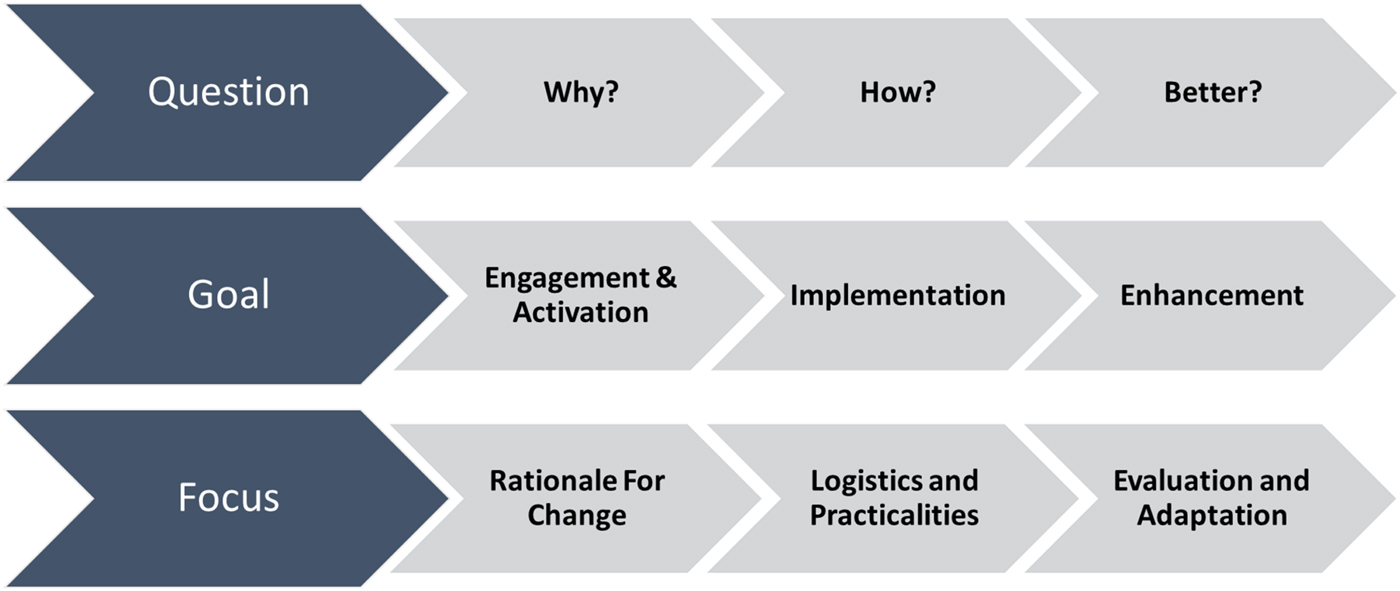

From a practical perspective, we propose three key phases for faculty development related to competence by design (Figure 1). Prior to and during implementation, the main question to answer is why are we changing? Explaining the rationale for change, including problems with the old and a roadmap forward, is required. During implementation, the question to answer is how do we do this? Here, it is the logistical and practical activities that need to be addressed such as how to login to novel electronic portfolios and how to fill out assessment forms. Activities can take the form of practical workshops, online tutorials, or just-in-time teaching in the workplace. Finally, soon after implementation, we can start to address the most important question, how can we do this well? This important phase, whose goal is enhancement, will require a sustained and multi-pronged effort, and it is not the time to become complacent once everything is up and running.

Figure 1. Phases of faculty development for competence by design implementation.

Identified by Chan et al.Reference Chan5 as the most desired content for faculty development, the delivery of high-quality coaching feedback is the most critical area to focus sustained efforts. Front-line faculty on whom this responsibility falls deserve appropriate training and support, because if they do not engage in this activity, the processes of competence by design will fall apart.Reference Nousiainen, Caverzagie and Ferguson8 Much like the impact of systematic review depends on the quality of its primary articles, the effectiveness of a competence committee is only as good as the front-line observations and coaching feedback that are delivered to the trainee.Reference Nousiainen, Caverzagie and Ferguson8 Much has been written about the provision of high-quality feedback for medical trainees, and this has been a common faculty development activity for physicians for many years.Reference Bing-You, Hayes and Varaklis9 However, the newly found enthusiasm for improvement of coaching feedback on the front-line presents an opportunity to affect significant change. We now have an enormous amount of assessment data from front-line faculty that not only will help our trainees but also can be analyzed and utilized as material for faculty development. In addition to typical activities like workshops and email or paper tips and tricks, assessment data can be used for peer coaching and to facilitate both individual faculty and institutional growth. Effective feedback coaching for competence by design should move beyond the typical features of quality feedback and focus on normalizing frequent constructive feedback, encouraging credible and trusting teacher-learner interactions, and helping faculty negotiate the tensions between assessment and feedback.Reference Watling and Ginsburg10

As an innovation in medical education, the implementation of competence by design, or Residency 2.0, is disruptive and demands faculty development in every EM training program around the country. After the frustrations of implementing the logistics and practicalities of competence by design have been overcome, a focus on the delivery of high-quality coaching feedback in the workplace can be taken to support the physicians on the front-line. Regardless of the methods chosen, this focus is critical to the implementation of competence by design and the success of our trainees in caring for our patients. We encourage our departments and residency training programs to embrace the opportunity for faculty development that the transition to competence by design has precipitated.

Competing interests

None.