Introduction

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a frequently diagnosed condition in the pediatric emergency department (ED). It especially affects young children presenting with fever of unidentified source, accounting for 5% of cases.Reference Hoberman, Chao and Keller 1 , Reference Shaw, Gorelick and McGowan 2 Early diagnosis is important in order to prevent complications and detect urinary tract malformations. 3 - Reference Smellie, Poulton and Prescod 5

Collecting a reliable urine specimen is challenging in children who have not been toilet-trained. Urethral catheterization (UC) is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics 3 and the Canadian Pediatric SocietyReference Robinson, Finlay and Lang 6 for this purpose, and is routinely used in many EDs. Even though studies have found this procedure to be unpleasant,Reference Maclean, Obispo and Young 7 - Reference Mularoni, Cohen and DeGuzman 10 very few have looked at short-term adverse events.Reference McGillivray, Mok and Mulrooney 11 - Reference Robson, Leung and Thomason 14 Furthermore, these studies looked at intermittent UC and urologic procedures,Reference Gladh 15 - Reference Uehling, Smith and Meyer 20 which is very different from the diagnostic UC performed in the ED. Only one prospective study specifically evaluated the proportion of adverse events following UC performed in the ED, and this study found a complication rate of 4.5% at one month.Reference Hernangómez Vázquez, Oñoro and de la Torre Espí 21 However, the study did not include earlier follow-up and did not look at the severity and impact of these complications. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Pediatric Society recommend UC to diagnose UTI in young children, no data on complications related to this procedure are mentioned in their UTI guidelines. 3 , Reference Robinson, Finlay and Lang 6

We conducted this study to assess adverse events in the week following diagnostic UC performed among young children in the pediatric ED, and to measure the impact of these complications on the patient and their family.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

This was a prospective observational study in the ED of a pediatric university-affiliated tertiary-care center (Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center, Montreal, Canada) from February 5, 2013 to November 5, 2013. Patients were eligible if they were aged 3-24 months, had a history of fever (≥38°C/100.4°F) in the last 24 hours or documented at triage, and had undergone a UC in the ED. Exclusion criteria were the following: UC performed for a reason other than fever, Foley catheter placement, intermittent catheterization at home, coagulopathy, immune deficiency, vesicostomy, urostomy, the family did not speak English or French, and previous inclusion in the study.

Study protocol

In our setting, UC was performed by a nurse assisted by an attendant, using a sterile technique. Meatus is initially cleaned with sterile water before cathether insertion (8 F). Most UC were performed in one attempt, with a maximum of two attempts.

Parents were invited to participate if their child met all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Recruitment mainly occurred during weekdays from 9 AM until 7 PM, because of the research assistant schedule. Parents of eligible children were approached by the research assistant after UC had been performed in order to avoid influencing their consent to the procedure. Written consent was obtained from parents on the information/consent form. English and French versions were available.

Parents consenting to the study received a phone call seven to 10 days after their visit to answer a short questionnaire inquiring about potential catheterization complications. The phone call was performed by a bilingual research assistant and a standardized data form was completed. The questionnaire included information about demographics and outcomes (see outcome section). If unreachable, parents were called back at least two times in the following days. Questionnaires were non-nominal and kept locked to ensure confidentiality. The study protocol was approved by Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center’s Institutional Review Board.

Outcome

The primary outcome was a composite outcome defined as the occurrence of at least one adverse event in the week following the UC, including: painful urination, genital pain, urinary retention, gross hematuria, and UTI secondary to UC. All components of the composite outcome were deemed secondary to the urethral traumatism engendered by catheterization. Painful urination was defined as crying while urinating and urinary retention as refusal to urinate. A UTI was diagnosed if urine culture showed presence of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per mL of a uropathogen. A child with a positive urine culture on the initial urine test was considered as having a primary UTI. A UTI secondary to catheterization (or “secondary UTI”) was defined as the occurrence of a UTI which was absent on the initial urine test.

To ensure the inclusion of only new symptoms potentially caused by UC, parents were asked if symptoms considered as adverse events were present before catheterization. Symptoms that were present before UC were classified as negative (not a new occurrence of adverse event). This allowed us to draw conservative estimates.

Secondary outcomes included the occurrence of an adverse event leading to subsequent health-related intervention (including medical visit, other tests, or treatment) or missed day of school or work for the parent. As a hypothesis-generating sub-study, we also evaluated the following independent variables potentially associated with adverse events: age, sex, past history of UC and hematuria (defined as >5 red blood cells per high power field on microscopic analysis) on the index urine sample.

Data analysis

Data were entered in an Excel database (Microsoft Inc., Richmond, WA) and analyzed using SPSS v21 software (IBM Software Group Inc.). The primary analysis was the proportion of participants who had an adverse event. Secondary analyses included the proportion of patients who had multiple complications, the proportion of parents who missed school/work, and the proportion of children who needed further medical care for complications following catheterization. In order to determine the impact of UC and the symptoms related to UTI, a secondary analysis was performed, excluding children with a final diagnosis of UTI. The 95% confidence interval was calculated for each measurement. As an exploratory analysis and to generate new research hypotheses, we performed a secondary analysis to identify factors associated with a higher risk of adverse events (see above) using logistic regression. All independent variables having a p value<0.05 on single logistic regression were included in a multiple logistic regression.

Sample size was estimated based on the previous study that reported an adverse event rate of approximately 5%,Reference Hernangómez Vázquez, Oñoro and de la Torre Espí 21 and the desire to have a 95% confidence interval, having a 7% margin for proportions. It was estimated that enrollment of 200 patients would provide a confidence interval from 3% to 9% if 10 patients had a positive outcome, and from 43% to 57% in the worst case scenario where the adverse event proportion was raised to 50%.

Results

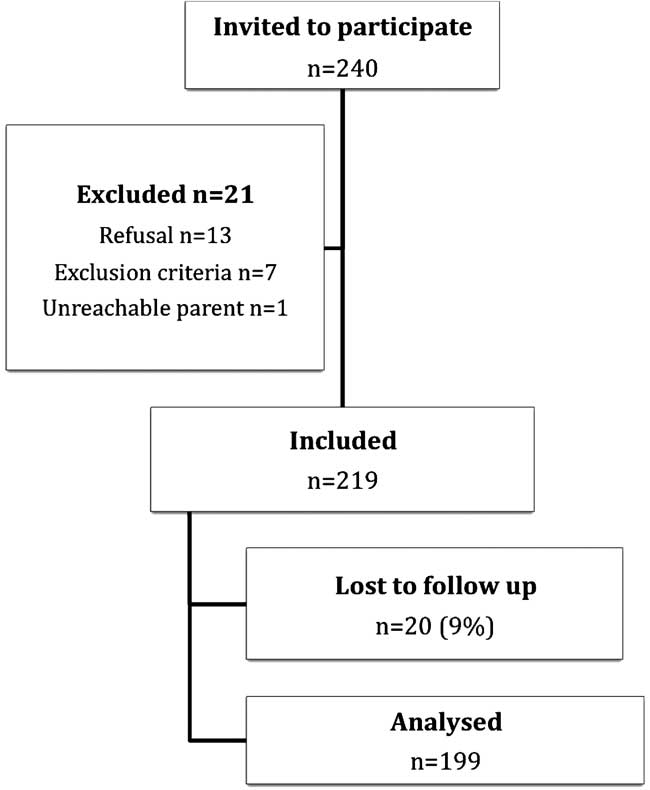

A total of 240 children fulfilled the inclusion criteria during the presence of a research assistant (Figure 1). Among them, 219 were included in the study. The reasons for non-inclusion were parental refusal to participate (13/21), followed by exclusion criteria (7/21), and parent stating that he or she would not be reachable (1/21). Among patients whose parents agreed to participate, 20 were lost to follow-up (parents were not reached by phone at seven to 10 days). Patients who were lost to follow-up had similar baseline characteristics compared to those for whom complete data were gathered (Table 1). The primary analysis was conducted on the 199 patients for whom there was information about the primary outcome.

Figure 1 Flowchart.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study participants and of children lost to follow-up

UC: urethral catheterization; UTI: urinary tract infection

The median age of study participants was 10 months, and 45% were male (Table 1). Almost a third of children had a past history of UC. UTI criteria were fulfilled in 43 (22%) children. Of these, seven (17%) had a negative urinalysis and a positive culture. Only two patients with a positive urinalysis were later found to have a negative culture and were not included as having UTI. At the time of UC, no patient already had or presented with gross hematuria, but microscopic hematuria was identified in 29 (15%) children on the index urine sample.

Among the 199 study participants, the parents of 41 children (21%) reported at least one complication (Table 2). Two or more complications were reported in 6% of children. The most common complications were new onset of painful urination (10%), genital pain (8%), and urinary retention (6%) (Table 3). Gross hematuria was reported in nine (4.5%) children. The parents of three (1%) children visited a health care facility for a complication possibly related to UC. These complications were painful urination, new onset hematuria and secondary UTI. Only the last case required further intervention (venipuncture, 10-day course of oral antibiotics, renal ultrasound, and follow-up at an outpatient clinic). Three families (1%) reported having missed work or school because of an adverse event potentially related to UC, but only one (0.5%) visited a health care facility for that complication. The proportion of each complication was similar in the patients with a primary diagnosis of UTI compared to those without UTI (Table 3).

Table 2 Number of complications reported in study participants (n=199)

Table 3 Presence of each complication in all study participants (n=199) and in children without urinary tract infection (n=156)

UTI: urinary tract infection

Two independent variables (male sex and age 12 to 23 months) were statistically associated with a higher risk of having adverse events on single and multiple regression (Table 4). Previous UC first appeared to be associated with a higher risk of complications (OR: 2.08) but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.041). Microscopic hematuria at the time of UC was not associated with a higher risk of adverse events.

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate association between risk factors and complications following UC

UC: urethral catheterization; UTI: urinary tract infection

Discussion

In this study, we found a 21% rate of adverse events in 3- to 24-month-old children who had a diagnostic UC in the ED, which is higher than expected. Physicians probably tend to underestimate UC-related complications because patients rarely seek medical care for them. This was clearly demonstrated in our study population, where only three families consulted for an adverse event. Although most of these complications appear minor, they can still cause significant distress to children. This should be kept in mind before ordering a UC.

To date, only one study has looked at adverse events following diagnostic UC in the ED. In their study published in 2011, Hernangómez Vázquez et alReference Hernangómez Vázquez, Oñoro and de la Torre Espí 21 reported a 4.5% complication rate in 116 children, one month after UC, using a phone call to parents as follow-up method. Children aged less than 3 months old accounted for 30% of their population. The higher complication rate found in our study may result from at least two things. First, to minimize recall bias, we chose to call parents at one week instead of one month, considering complications would probably occur in the first few days following UC. Secondly, we did not include children younger than 3 months. We hypothesised that the younger the child, the harder it would be for parents to assess complication occurrence. This is suggested by the fact that, in our study, older age (12-23 months) was strongly associated with a higher risk of adverse events. In another prospective study, GladhReference Gladh 15 reported urgency/painful urination and UTI in 12% and 3%, respectively, of 99 children who had an elective UC for micturition-urethro-cystography or cystometry. Median age in this study was six years. Painful urination and UTI occurred in a similar proportion of children in our study (9.5% and 0.5% respectively).

According to our results, complications occur more frequently in boys than in girls, which is consistent with Hernangómez Vázquez et al,Reference Hernangómez Vázquez, Oñoro and de la Torre Espí 21 who found 60% of their complications in boys. This can be explained by UC often being more difficult to perform in boys due to the longer length of their urethra. We also found older age (12-23 months) to be associated with a higher risk of complications. The median age of children with complications was also higher than the median age of the study population (12 months vs 7 months) in the aforementioned study.Reference Hernangómez Vázquez, Oñoro and de la Torre Espí 21 The more advanced communication skills of older children is likely the explanation for this observation. The fact that urinary retention is easier to recognize in an older child and that efforts to restrain older children for UC may render the procedure harder to perform could also explain this finding.

Although we feel it is hard to assess the real benefits of UC in our population, we can deduce that it changed management in at least nine patients. In the seven patients who were found to have culture-proven UTI with a negative urinalysis, parents were contacted to organize follow-up and antibiotic treatment. Unnecessary antibiotic therapy was stopped early for the two patients with a falsely positive urinalysis. Overall, UC enabled clinicians to diagnose UTI in 43 children, which led to an early management in order to avoid complications.

There are limitations to this study. First, there was no standardized definition for some of the outcomes (painful urination, genital pain, and urinary retention). Evaluation of these relied on parental assessment. The advantage of this approach was to identify adverse events as the parents “felt it.” Previous studies have reported that parental pain scores can be reliably used as a surrogate measure in children.Reference Khin Hla, Hegarty and Russell 22 , Reference Voepel-Lewis, Malviya and Tait 23 However, urinary retention itself may have been misdiagnosed in some cases. The long-term impacts of UC were not evaluated in this study. These impacts could potentially be physical (e.g., urethral trauma) or psychological. This suggests that our results are an under-estimation and conservative. Moreover, we did not consider whether some form of analgesia was used during UC, an intervention that could potentially reduce the incidence of some complications in the hours following the procedure. We also chose not to look at the number of attempts performed or whether the procedure was traumatic, because we wanted to avoid influencing the way UC was performed in our ED. These two factors were possibly associated with more adverse events. Another limitation ensues from the fact that our study was done in a single center and without a control group, limiting the external validity of our results. We found a surprisingly high rate of previous UC (33%), which can be partly explained by a high number of patients with comorbidities in our ED compared to others. Considering that this characteristic was not associated with a higher risk of complications, the impact on external validity is questionable.

Conclusions

Urethral catheterization was associated with adverse events in one-fifth of young children in the week following the procedure, even though parents rarely sought medical care for them. Accordingly, clinicians should balance the risks and benefits of this procedure before ordering it, keeping in mind the best interest of each of their patients.

Given the observed complication rate, we suggest that this data be added to clinical guidelines on UTI diagnosis and management in children.

Competing Interests: None declared.