Introduction

Fundamental discoveries are well accepted. The historical descriptions of their establishment are often standardized, involving the same actors set in chronological order. Archimedes’ ‘Eureka’, as told since Vitruvius, is a typical example. However, this represents a historically and socially constructed concept as a natural fact and engenders a dominant, one-sided view. This is a weighty issue to shuffle lasting discourses of imperialism, in particular for inventions made in the ‘Orient’, in order to propound more inclusive views of the present, the future and the past.

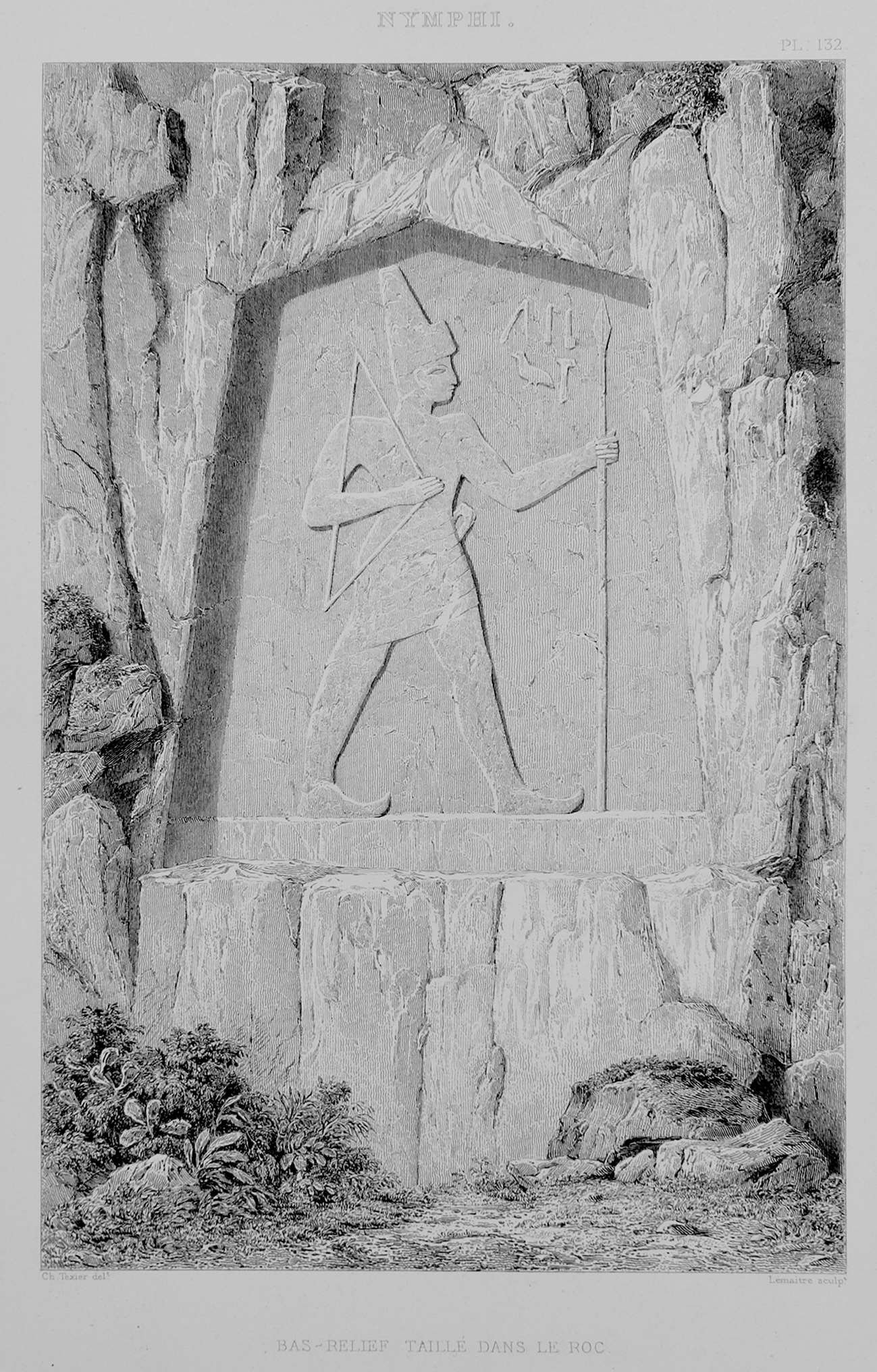

The rock-relief figure of Karabel (today in Izmir Province, western Turkey) is arguably a corner stone in ‘oriental’ archaeology (Fig. 1). First identified as Sesostris, an idealized pharaoh described in Herodotus’ Histories, it has been seminal in attracting early western adventurers looking for ‘their’ past (Fig. 2a. See Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846; Texier Reference Texier1849; Tyler Reference Tyler1888). A few years after this first identification, it was recognized as an artefact of the Hittite civilization and played a pivotal role in helping to understand that the core land of the Hittites should be located in Anatolia and not in Syria (Sayce Reference Sayce1880). Hence it was central in forging the key features of the Hittite civilization (Bittel Reference Bittel1976; Darga Reference Darga1992; Vieyra Reference Vieyra1955). Finally, in 1998, the inscription was successfully read and the relief identified with a representation of Tarkasnawa, king of Mira, not a ‘Hittite per se’, but a vassal king of the Hittites (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1998).

Figure 1. Map of the location of Karabel, 30 km east of Izmir (Turkey). (Data: OpenStreetMap (2021) and SRTM (NASA JPL 2013); realized with R (R Core Team 2022) and the library tmap (Tennekes Reference Tennekes2018). Code provided in Strupler Reference Strupler2022a.)

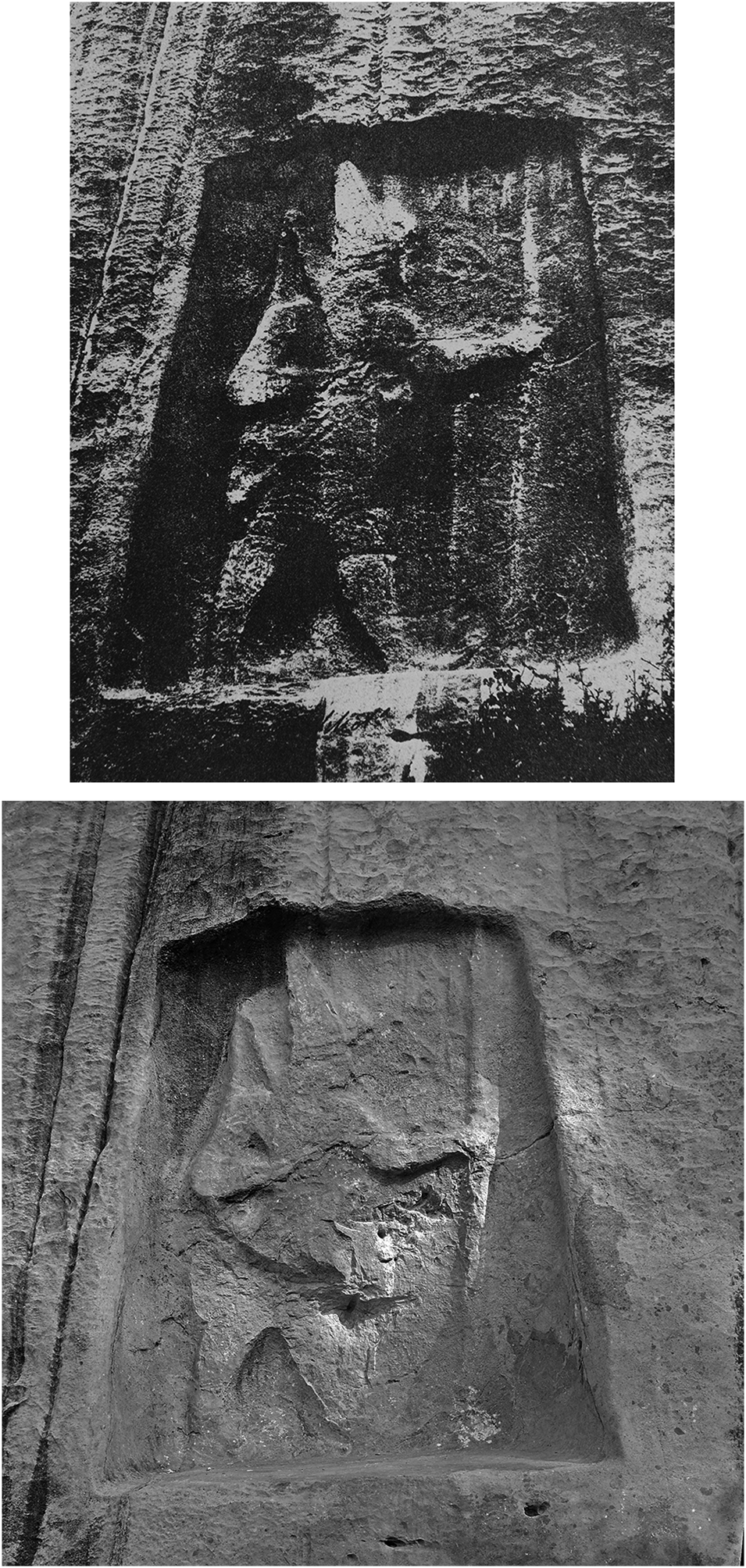

Figure 2. (above) Photograph taken by Svoboda and published in Perrot & Guillaume (Reference Perrot and Guillaume1866). It depicts the main (and only surviving) relief of Karabel, first considered to be the pharaoh Sesostris and now interpreted as the king of Mira, Tarkasnawa; (below) Photograph of the relief of Karabel taken in 2019 by the author. The extent of the damage is clearly visible on the legs and in the middle of the relief, accentuated by a drilled hole.

Despite its historiographical importance and the numerous articles and papers discussing the Karabel figures and inscriptions, it seems that the ‘self-evident’ idea of protecting (i.e. not damaging) it did not find unchallenged recognition and acceptance. Some blocks with inscriptions in the surroundings ‘disappeared’ between 1977 and 1982, when the mountain-pass road was expanded for car traffic (Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983). Recently, direct damage has been inflicted on the main rock relief (Fig. 2b. See Müller-Karpe Reference Müller-Karpe2019; Tulunay Reference Tulunay2006). This continuous harm during the last 50 years asks the archaeological community to look at potential reasons for the destruction and how potentially to mitigate it—if we want the relief to survive. What message(s) does this relief carry that is worth the effort of deliberate destruction in the twenty-first century? Finding gold?

An interdisciplinary framework is proposed here to examine the contexts that refer to the Karabel relief. Specifically, I will focus on the historiography of the Hittites and consider how this rock relief is a milestone in the story of the so-called re-discovery of a ‘forgotten’ civilization. In examining traditional accounts about the discovery of Karabel and Hittites, I lay out the common narrative structure, which transforms the story of (the life of) the Karabel monument into a kind of hagiography. This consensual structure is put into perspective with an introspective reflection that incorporates critiques from post-colonial studies, revealing the accumulated bias in ‘knowing the orient’ (Asad Reference Asad and Asad1973; Kohn & Reddy Reference Kohn and Reddy2017; Said Reference Said1978). The relational approach applied here highlights the entanglement of ‘the Orient’ and historiography, which—I hypothesize—instead of creating a common ground of understanding may have missed the opportunity to avoid the radical rejection of the Karabel relief by some people. The discussion acknowledges that there can be no certainties or direct connections between narratives and re-actions: only implicit links can be suggested, and potentially addressed with the hope of protecting the monument by reformulating its signification for today's and tomorrow's human groups. This article is theory-in-practice: it showcases the pitfalls and in so doing tells a story with more diversity, open thoughts and considerations beyond traditional narratives of power in passéist oriental archaeology.

Situating Karabel

During the Ottoman period, Izmir (also then called Smyrna) was an important harbour city for people travelling from Europe to Western Asia as well as a physical and administrative interface for a journey further into the countryside of Asia Minor. Karabel is located roughly 30 km east of Izmir, on the side of a pass road linking two valleys (Fig. 3). It was therefore possible to visit the monument by horse within a day from Izmir, and thanks to this accessibility it was one of the first non-classical monuments discovered in the ‘Orient’. The monument is roughly 1.5 m wide and 2.5 m high (Fig. 2). It depicts a figure standing with a bow in the right hand and a spear in the left. Between the head and the spear there is a hieroglyphic inscription. In the accounts of the ‘rediscovery of the Hittites’ (Güterbock Reference Güterbock and Sasson1995; Klinger Reference Klinger2007; Sayce Reference Sayce1880), the story goes that ‘we’ lost all knowledge of the Hittites, aside from the fact that they are mentioned in the Bible (Gerhards Reference Gerhards2009; Singer Reference Singer, Maeir and de Miroschedji2006; Wright Reference Wright1886).

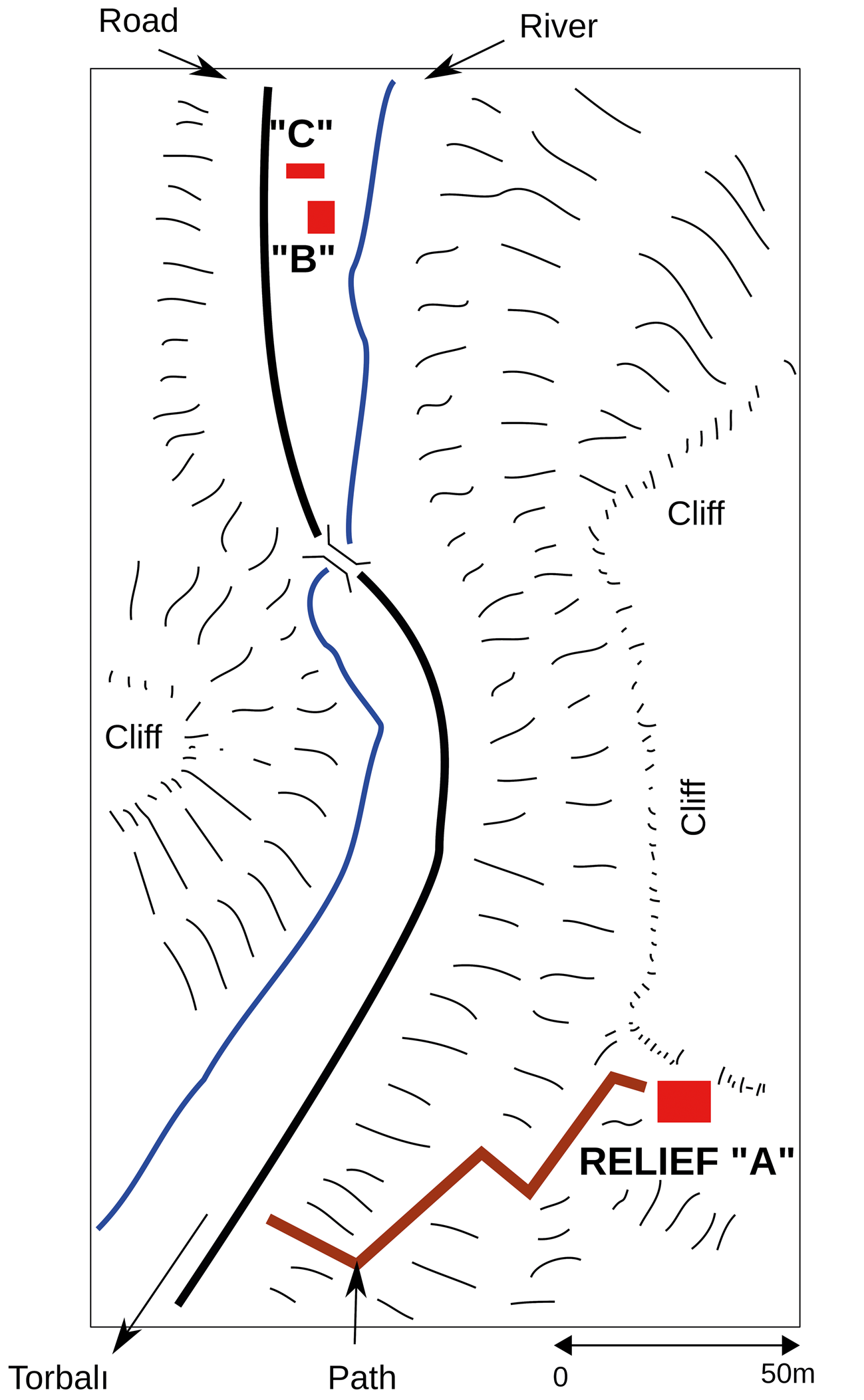

Figure 3. Plan with the position on a rock cliff of the main relief A representing Tarkasnawa. One partially conserved relief B (similar in size and subject to relief A, but only the bottom was conserved) and two other inscriptions C1 and C2 were later discovered, on the terrasse of the riverbank. Relief B and inscriptions C1 and C2 were destroyed by the end of the 1970s when the road was enlarged and paved with asphalt. (Plan adapted from Bittel Reference Bittel1939, fig. 2, who visited the location in 1936 and 1940.)

Karabel was first rediscovered by oriental travellers in the early nineteenth century (Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843; Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1840; Reference Lepsius1846; Texier Reference Texier1849). From this event onwards, French, German, British and other scholars argued at length about the identity of the first discoverer (recently Müller-Karpe Reference Müller-Karpe2019). It is not clear when Karabel was ‘discovered’,Footnote 1 but it starts to be mentioned frequently in travelogues from the 1830s onwards. Awareness of the relief is attested in Izmir among western travellers prior to 1814 (Cook Reference Cook1956; Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983). Already in the 1840s, every article started by explaining how the knowledge of the existence of the relief was transmitted. Leonhard Schmitz (Reference Schmitz1844) dedicates a notice about the ‘correct’ identity of the discoverer. He attributes it to Reverend George C. Renouard when he was chaplain in Izmir (1811−14) and he cites a publication from 1832 to sustain his claim (Renouard Reference Renouard, Smedley, Rose and Rose1832, col. 435c). More than half a century later, this ‘fact’ made it into its biography: ‘His [i.e., George C. Renouard] priority of discovery was afterwards disputed, but it was finally vindicated by Dr. L. Schmitz in the Classical Museum’ (Boase Reference Boase1896). The importance given to the ‘priority of discovery’ acknowledges the need to affirm the author's authority. This asserts the existence of the relief, transforming it into a real fact (see Stengers Reference Stengers1991; Reference Stengers2000, 88–108). When Karl Lepsius made his in(ter)vention at the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, an account published in the form of a cursory note without the drawing (Lepsius Reference Lepsius1840), his point was to announce this ‘discovery’ to the ‘world’. He builds a first history of the monument, by listing the people who saw it, before describing it. He argues that the carving corresponds to the relief of the pharaoh Sesostris related by Herodotus (see Cook Reference Cook1956; or West Reference West1992 on Herodotus and Sesostris). If another example is necessary, the same can be said about Karabel's relief B. This relief was found 100 m north of the main relief, on the terrace of the river in the bed of the valley (Fig. 3). British and American scholars (Jensen Reference Jensen and Hilprecht1903, 755; Luckenbill Reference Luckenbill1914, 25; Sayce Reference Sayce1882, 267), but not French German scholars, stress that relief B was discovered by John Beddoe in 1856, a fact that Beddoe diligently underlined in his memoirs: ‘apparently I was really the first of Europeans to see this duplicate figure. Seventeen years later it was shown to, or found out by, a German gentleman [i.e. C. Humann], who got much credit for the discovery’ (Beddoe Reference Beddoe1910, 97). Hyde Clarke, a merchant-engineer active in Smyrna in the 1860s, wrote several notices to assign the discovery of a second relief to the Prussian Consul Ludwig Spiegelthal: ‘in 1866 Mr. Spiegelthal informed me of a slab being found, which we considered must be the second Sesostris, but, however, we did not go to it. Dr Beddoe, F.R.S., must also have been close to it about 1856. It was, however, Mr. Humann's memoir in 1875 which made it known’ (Clarke Reference Clarke1879, 79, col. b; see also Reference Clarke1866; Reference Clarke1868; Reference Clarke1875).

Heinrich Kiepert was the first academic to challenge the interpretation that the relief at Karabel was an (ancient) Egyptian representation (Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843; West Reference West1992). He draws attention to the differences between the style of the Karabel figure and ancient Egyptian art. Astutely, he suggests that even if the relief corresponds to the formal description of Herodotus, maybe Herodotus was wrong in identifying it with a pharaoh. Kiepert notes that the signs are not Egyptian hieroglyphs. Instead, he connects the relief with the drawings from Yazılıkaya, in the meantime made accessible by Texier in his first travelogue volume (Reference Texier1839). By 1879/1880, Archibald Sayce went on to observe that these hieroglyphic signs are the same as attested elsewhere in Anatolia and Syria and stated that the core area of the Hittite empire lay not in Syria, but in Anatolia, considering Karabel a representation of a Hittite King by linking it to the already famous bigraphic ‘Tarkondemos’ seal (Alaura Reference Alaura2017b; Sayce Reference Sayce1879; Reference Sayce1880; Tyler Reference Tyler1888).

Then, for more than a century, the relief was discussed and reproduced in innumerable articles about the Hittites, notably to introduce them (Alaura Reference Alaura, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017a,Reference Alaurab; Bryce Reference Bryce2002, 1; Collins Reference Collins2007, 3; Güterbock Reference Güterbock and Sasson1995; Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1887, 10; Jensen Reference Jensen and Hilprecht1903; Klengel Reference Klengel1999, 5–10; Seeher Reference Seeher and Willinghöfer2002; Weeden Reference Weeden, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017). The main questions addressed are the dating, reading of the inscription and the particularity of its style (Bittel Reference Bittel1939; Reference Bittel1967; Garstang Reference Garstang1929, 176–9; Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846; MacQueen Reference MacQueen1986; Perrot & Guillaume Reference Perrot and Guillaume1866; Ramsay Reference Ramsay1927, 140–81; Steinherr Reference Steinherr1965). The relief was made available in Europe and North America when Hirschfeld made a cast in 1874 for Berlin, copied and dispatched to several museums (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1887, 6; list of museums with a cast listed in Bittel Reference Bittel1967, n. 5). Recent 3D scanning of the cast may provide future access to digital replication (Schachner Reference Schachner2018, 60–65). A ‘breakthrough’ in interpretation dates from 1998, when a new reading of the inscription made by David Hawkins reached a broad consensus. The relief is considered the representation of Tarkasnawa, king of Mira, a Luwian vassal to the Hittite King (Hawkins Reference Hawkins1998; Müller-Karpe Reference Müller-Karpe2019). Currently, it is a central piece of evidence for discussing the geographical history of the Hittites revealed by cuneiform texts, especially wars, conquests and territories in western Anatolia (Gander Reference Gander2017; Glatz & Plourde Reference Glatz and Plourde2011; Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2015b, 90–93; Meriç Reference Meriç2021; Seeher Reference Seeher2009).

De-centring Karabel

Typically, when the Karabel relief is introduced, scholars take tremendous care to discuss when and why it was carved, and how it was perceived in the second millennium bce. Due to the extraordinary ‘afterlife’ history of the relief, scholarly discussions often deal with Herodotus’ statement and the monument's re-discovery in the nineteenth century ce. Subsequently the accounts concentrate their attention on the latest scholarly works and debate the best interpretation. This has already been criticised by Ömur Harmanşah (Reference Harmanşah2015b), who argues that instead of focusing on the (main) moment of creation, rock monuments, because they are visible across time, offer an opportunity to research local practices diachronically and the multiple ‘horizons of meanings’ throughout history (Reference Harmanşah2015b, 2). He contends that accounts should deal with the multitemporality of rock monuments, such as the geological setting, or significations (ideological, social, and political) before the erection, during the creation and the ‘afterlife’ of the monument. He rightly suggests that ‘place-based approaches also successfully deconstruct the colonial and conservative understanding of archaeological landscapes as things of the past seen through a fixed chronological window opening onto the distant past’ (Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2015b, 13). However, when he discusses Karabel (Reference Harmanşah2015b, 88–9, 98–9), the same periods as usual are mentioned: the time of creation (thirteenth century bce), Herodotus’ mention (fifth century bce), oriental travellers’ ‘re-discovery’ of Karabel (nineteenth century ce), and finally current scholarship. Harmanşah follows most of the authors and discusses neither vandalism nor destruction, nor does he deal he with how the monument is presented today, noting only in passing, ‘on the lower slopes […] three other relief carvings […] have been reportedly destroyed during a recent road construction’ (Reference Harmanşah2015b, 98). His main contribution regarding Karabel is the interpretation of the relief in the second millennium bce as a site of memory. Yet I hypothesize in the next section that the archaeological community, by creating and maintaining this idealized biography of a founding figure, has crafted a ‘hagiography’. This account is silencing living local communities—people living in the surrounding villages and cities (Fig. 1)—and their re-actions. It faithfully follows the classical oriental tradition.

Visualizing Karabel's hagiographic amnesia

It is striking how stereotypically scholarly articles deal with Karabel. Despite the high number of mentions in articles, the same events and persons are highlighted, often in the identical chronological order. One reason for the survival of this traditional form is clearly the appeal of a ‘heroic biography’, making it easier to write a captivating history for the public (on the persistence of this tradition in biographical account, see Riall Reference Riall2010, 382–6). Without doubt, in the case of Karabel, this has been encouraged by the role of Karabel as a cornerstone in ‘resuscitating’ this civilization (Güterbock Reference Güterbock and Sasson1995). Nevertheless, describing a life as a coherent whole, following a logical chronological order, is in fact an artificial concept. It is presented as if it were natural, but it is instead a historically and socially anchored myth (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Hemecker and Saunders2017, 210; commented in Kolkenbrock Reference Kolkenbrock, Hemecker and Saunders2017).

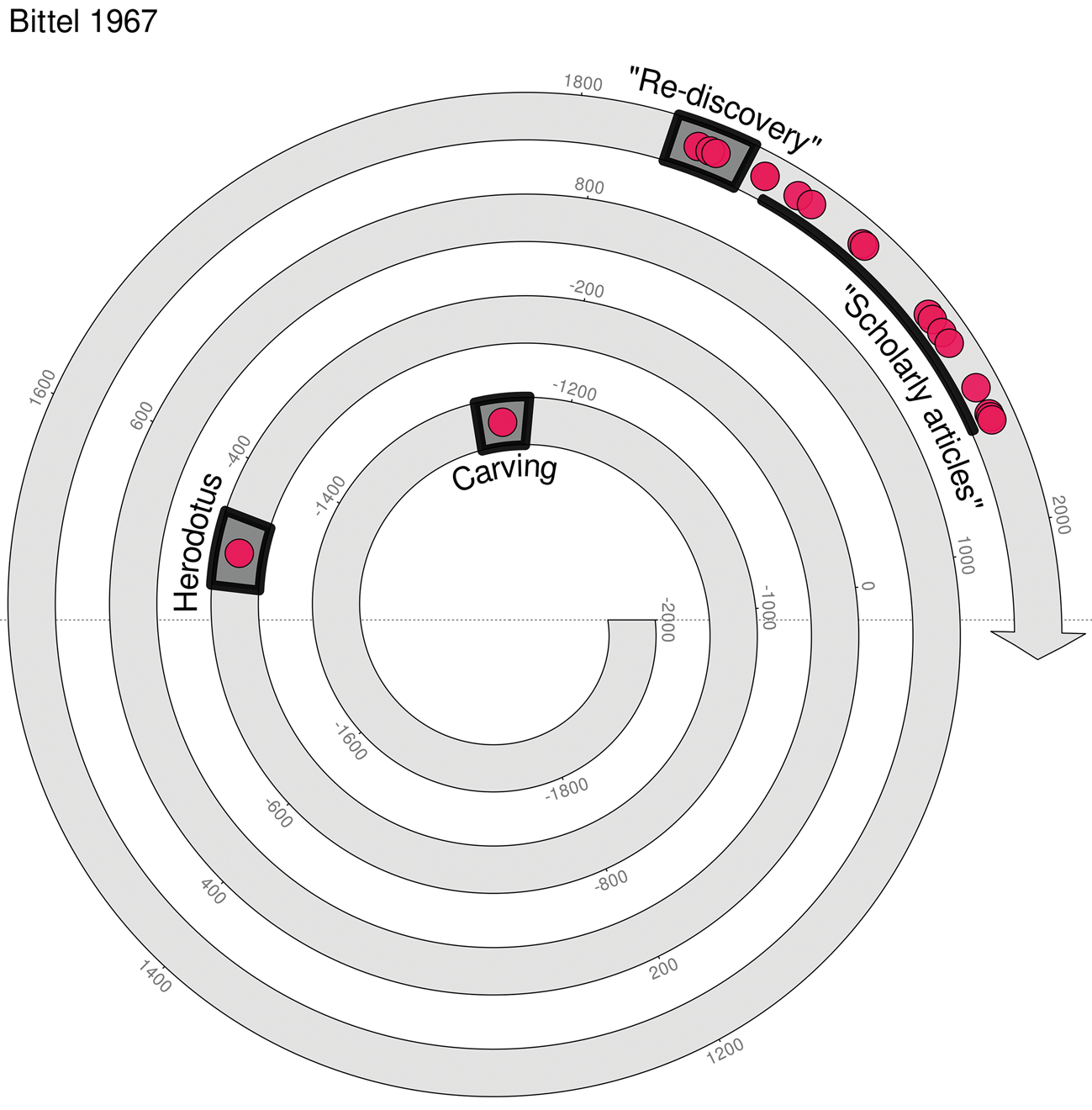

Indeed, if we look at one of the earliest articles about Karabel, the second article by Lepsius (Reference Lepsius1846), and if we draw the events referenced on a timeline, then the ‘time discrimination’ becomes evident (Fig. 4). The history of the monument is patchy. It starts with the carving of the relief, then jumps to Herodotus’ mention, then jumps again to the nineteenth century ce. More than a century later, when Bittel (Reference Bittel1967) provided a synthesis of the monuments, the selection of events worth mentioning is the same, with the addition of recent studies from western scholars (Fig. 5). Finally, when in reaction to the recent damages to the monuments Müller-Karpe (Reference Müller-Karpe2019) made a synthesis of Karabel and its connection with Herodotus, the selection of persons acknowledged remains similar, with the addition of recent works (Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Timeline with the events acknowledged in Lepsius (Reference Lepsius1846), visualized along an Archimedean spiral for high resolution despite the long time axis (c. 4000 years). It starts with the carving of the relief by the sculptor attributed to the time of Ramses (c. –1250), followed by Herodotus’ description (c. –450). After more than two millennia of amnesia, Lepsius tells the story of the rediscovery and first interpretations, starting with George C. Renouard's conversation in London about Karabel in 1839. This is followed in the same year by the transmission of a drawing of Karabel (made by Charles Texier) from the dragoman Baron of Nerciat to Baron (Alexander) von Humboldt, who gave it to Karl Lepsius (Lepsius Reference Lepsius1840). The article continues first with Kiepert's interpretation, who visited the monument in 1843 (Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843); second with a note by Prof. Welcker (Reference Welcker1843) and finally relates Lepsius’ own visit in December 1845 (Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846). (Graphic realized with R (R Core Team 2022) and the library spiralize (Gu & Hübschmann Reference Gu and Hübschmann2021) with code available (Strupler Reference Strupler2022b).)

Figure 5. Timeline with the events acknowledged in Bittel (Reference Bittel1967), which follows the same pattern as Lepsius (Reference Lepsius1846). Bittel starts his account of the discovery with Charles Texier's drawing (Texier Reference Texier1849) followed by a list of authors of early drawings (Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846; Moustier Reference Moustier1864), the ‘first’ photograph (realized by Sandor Alexander Svoboda and published in Perrot & Guillaume 1866*), as well as the realization of the casting and squeezes (Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1887; Sayce Reference Sayce1879; Reference Sayce1899; Reference Sayce1931). Then, he reviews the main different scholarly accounts (chronologically: Messerschmidt Reference Messerschmidt1900; Garstang Reference Garstang1910; Cook Reference Cook1956; Steinherr Reference Steinherr1965; Bean Reference Bean1966; Güterbock Reference Güterbock1967), before introducing his view. (Graphic realized with R (R Core Team 2022) and the library spiralize (Gu & Hübschmann Reference Gu and Hübschmann2021) with code available (Strupler Reference Strupler2022b).) *As a Swiss and French researcher, I am obliged to dispute here the priority of photography. Indeed, the first photo(litho)graph published of Karabel was realized by the French architect and photograph Pierre Trémaux, published in his interrupted serialized publication from his expedition in Anatolia (Trémaux Reference Trémaux1858, pl. Nymphaeum). However, it was quickly judged of ‘bad quality’ by peers (Reinach & Le Bas Reference Reinach and Le Bas1888, 45, pl. 49), and only Svoboda's later photograph has been picked up.

Figure 6. Timeline with the main researchers acknowledged in Müller-Karpe (Reference Müller-Karpe2019). After discussing Herodotus’ description, Müller-Karpe cites the different French, German and British accounts of the discovery (chronologically: Lepsius Reference Lepsius1840; Kiepert Reference Kiepert1843; Schmitz Reference Schmitz1844; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846; Texier Reference Texier1849; Curtius Reference Curtius1876; Sayce Reference Sayce1879; Hirschfeld Reference Hirschfeld1887). Then standard scholarly works are introduced and discussed (chronologically: Bittel Reference Bittel1967; Güterbock Reference Güterbock1967; Börker-Klähn Reference Börker-Klähn1982; Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983; Hawkins Reference Hawkins1998; Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2015b). (Graphic realized with R (R Core Team 2022) and the library spiralize (Gu & Hübschmann Reference Gu and Hübschmann2021) with code available (Strupler Reference Strupler2022b).)

We surely need to select some points in time to speak about the more than 4000 years of this monument. However, if we invariably select the same episodes, and we ignore the vast majority of activities from local people, we are streamlining the history. In his critiques of the biographical genre, Bourdieu notes that ‘this inclination toward making oneself the ideologist of one's own life, through the selection of a few significant events with a view to elucidating an overall purpose, and through the creation of causal or final links between them which will make them coherent, is reinforced by the biographer who is naturally inclined, especially through his formation as a professional interpreter, to accept this artificial creation of meaning’Footnote 2 (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Hemecker and Saunders2017, 211; see Kolkenbrock Reference Kolkenbrock, Hemecker and Saunders2017). This analysis is like the reflection of Virginia Woolf about how to write a biography. She stresses that even if the biographer ‘is bound by facts’, the author carefully selects which facts made the story (Reference Woolf, Hemecker and Saunders2017; cited in Caine Reference Caine2010, 85). When addressing the monument at Karabel, the biography of the monument merges with the biography of the represented person. Moreover, being part of fundamental well-accepted (re-)discovery, this creates another level of standardization and glorification. Lucy Riall, in her assessment of what she calls ‘the heroic model of biography’, places the origin of this genre in the nineteenth century, specifically in Britain, partly inspired by hagiographies, which narrated men's lives as examples for others to follow (Riall Reference Riall2010, 376–7). She adds, ‘it is revealing that their lives were typically told by the living members of the same elite groups’ (Riall Reference Riall2010, 378).

Picturing Karabel's source gap

In recent historiography, there is growing attention to the notion of ‘global history’, responding to the critique of the Eurocentric approach to history and science. Global history seeks to provide a framework that avoids privileging a unique (geographical) perspective, but instead recognizes, explains and discusses the interrelatedness, complexity and distinctiveness of different traditions of historiography (Little Reference Little and Zalta2020; Sachsenmaier Reference Sachsenmaier2010).

This problem of power relation in historic narrative has long been highlighted by proponents of bottom-up approaches often theorized under the umbrella of post-colonial or subaltern studies (Currie Reference Currie1995; Guha Reference Guha and Guha1982), ‘in which indigenous people play their part and that enable[s] them to reclaim their place in the present-day world’ (Dommelen Reference Dommelen, Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014, 469). E.P. Thompson shows similar considerations for historical writing (Reference Thompson1966, foretelling Bourdieu's critique of the biography). Thompson stresses that the ‘“Pilgrim's Progress” orthodoxy’ picks up only the elements that seem relevant for the current position of the writer and the grand narrative. He famously wrote ‘only the successful (in the sense of those whose aspirations anticipated subsequent evolution) are remembered. The blind alleys, the lost causes, and the losers themselves are forgotten’ (Thompson Reference Thompson1966, 12).

Some of the problems with the Eurocentric approach have been widely analysed in the case of the ‘Orient’. Scholars demonstrated how ‘Western’ researchers approached it with stereotyped conceptions, biases and oversimplified thoughts, and therefore reinforced a never-ending cliché of superiority, as Edward Said (Reference Said1978) writes in Orientalism (Little Reference Little and Zalta2020). Said, by describing the problems, methods and practices of generating and evaluating knowledge about “’non-Western’ peoples, shows that ‘knowing the Orient’ served and continues to serve to dominate it (Kohn & Reddy Reference Kohn and Reddy2017). Talal Asad (Reference Asad and Asad1973, 16) asserts that:

Anthropology is also rooted in an unequal power encounter between the West and the Third World [… and] gives the West access to cultural and historical information about the societies it has progressively dominated, and thus not only generates a certain kind of universal understanding, but also reinforces the inequalities in capacity between the European and the non-European worlds (and derivatively, between the Europeanized elites and the ’traditional’ masses in the Third World).

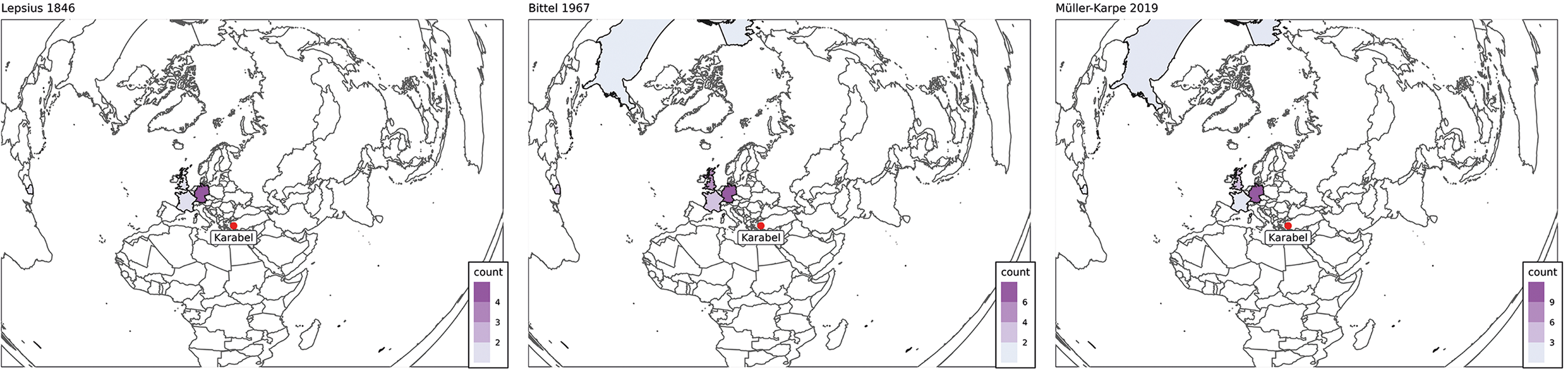

Analogous to the long-living tradition of ‘great men biographies’, in the case of Karabel too, biases in the origin of sources cited are persistent over more than 150 years. A case in point is, similar to the timelines presented above, the three cited papers (Bittel Reference Bittel1967; Lepsius Reference Lepsius1846; Müller-Karpe Reference Müller-Karpe2019). To illustrate the gap left for a more equal representation, I summed the number of actors in relation with Karabel by country of origin cited in those papers (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Maps showing the geographical repartition of the origin of publications cited in direct relation with the study of Karabel in the articles. We count (left) Lepsius (Reference Lepsius1846): Germany = 5, UK = 1, France = 1; (middle) Bittel (Reference Bittel1967): Germany = 8, UK = 5, France = 3, USA = 1; and (right) Müller-Karpe (Reference Müller-Karpe2019): Germany = 12, UK = 5, France = 2, USA = 2. For simplicity of demonstration and comparison, current political borders (2021) are used for the three maps. It is not the nationality of the researcher that has been considered, but the geographical position of their employer at the moment of the event or publication (thus, for example, Güterbock's publication (1967), then at the University of Chicago, is counted as an item from the USA). Code provided in Strupler (Reference Strupler2022b).

The side-by-side maps show three different spots in time (1846, 1967 and 2019), and indubitably demonstrate that even in the case of a monument situated in another country, it is the scientific productions from western countries that are cited and discussed. Researchers or other voices from the country in which the relief is now situated (Turkey) are almost excluded.Footnote 3 Based on these three articles, which are not quantitatively, but I would argue qualitatively, representative of the situation, we can conclude that Karabel is studied within a one-sided framework. The point I am trying to make is not that no one else wrote or interacted with the monument, or that Turkish scholars are not dealing with it, or that the locals did not consider it fascinating, but this is simply ignored. These papers turn the most ‘salient’ aspects of the monument's life into an idealized biography. By acknowledging the same historiography, they create a normative consensus, making it at each repetition more difficult to challenge, blurring the lines between biography and hagiography.

Fetishized representations

In the following sections, I would like to discuss the paradox that, despite the unequivocal value of the monument, it suffered recent episodes of damage. How can we read them? Should they be classified either under the category of vandalism, i.e. destruction by ‘ignorant people’, or as iconoclasm, an action conveying another meaning than simple ignorant destruction? (On the different meanings of these two words, see Gamboni Reference Gamboni1997, ch. 1.)

Altering monuments is not a recent phenomenon. It has been done across time and space. For example, in Mesopotamia figures have been defaced against their agency and to protect against their power (Bahrani Reference Bahrani1995; Reference Bahrani2017); or during the French Revolution to signal (re)appropriation (Clay Reference Clay2012b). The notion of heritage, however, has a much shorter history (Choay Reference Choay2009). Choay identifies a trend toward ‘fetishised’ heritages since the 1950s in abusing the power of monuments to foster identities (2009, 210–19). UNESCO plays a leading role in heritage globalization (Meskell Reference Meskell1998), as well as transferring ‘worldwide’ peace message to sites, especially in the context of the World Heritage List. This official recognition (and competition) incorporates the side effect of the potential transformation of sites into political ‘weapons’ to supply ‘soft’ power diplomacy (Meskell Reference Meskell2018; see particularly Luke Reference Luke2019 for a review of entanglements of heritage and American diplomacy in the Izmir region). Unsurprisingly, during wars, heritage is also regularly weaponized (Bevan Reference Bevan2016).

However, at first sight, current entanglement of globalization and world heritage does not seem to be the reason for the (mal)treatment of the Karabel reliefs. Unlike recent mass media on destructions (Flood Reference Flood2002; Harmanşah Reference Harmanşah2015a), neither records of ‘Karabel's amputation’ have been released, nor the actions proudly claimed by perpetrators. Despite its importance in academic circles, and accordingly its potential to be a famous attraction promoting a ‘thrilling’ story, the site is poorly known to the public. It was barely promoted in the last 50 years. During a visit in 2019, I laboriously searched for signposts on the road to the relief to indicate the way to it (Fig. 8). There was no place to stop, nor was public transportation available. No contextualizing signs were displayed (Fig. 9), and the setting in nature seemed to have changed only a little since the romanticized oriental vision of the relief in the middle of ‘nowhere’ (Fig. 10). Only some concrete stairs hidden in the bushes led from the road to the main relief. Why attack a relief hidden in the bushes?

Figure 8. View from the road with the barely visible signpost indicating the path to the relief of Karabel. Note that there is no place to park a car. (Photograph: taken by the author in September 2019.)

Figure 9. View of the relief of Karabel showing the absence of any kind of infrastructure or contextualizing sign. (Photograph: taken by the author in September 2019).

Figure 10. Orientalized depiction of the relief of Karabel, made by Landron to illustrate the archaeological travelogue of Reinach & Le Bas (Reference Reinach and Le Bas1888, pl. 59).

Destruction of relief B and inscriptions C1 and C2

Even if this is most of the time not addressed in scientific accounts, the ‘glorification’ of the monument has been regularly challenged. The unmaking of the Karabel reliefs is not a recent phenomenon and seems as old as the discovery of the reliefs by oriental adventurers. Commonly, the ‘unconsciousness’ of the alleged perpetrators is asserted. Already in the note by Curtius (Reference Curtius1876, 50), reporting Carl Human's re-discovery of the today ‘disappeared’ second relief B, in the river valley, it is stressed that:

According to the local people, the picture was completely preserved until last year, when a Yuruk (a nomad) pitched his tent in front of it and used the niche as a fireplace, which seemed more convenient to him with the block leaning towards the river. The marble cracked due to the fire and the pieces of the figure are piled up at its feet. The relief should have been depicted with a bow and hat just like the known one. Now only the feet, the left hand, and the spear are preserved.Footnote 4

This has been repeated by other scholars, such as Sayce (Reference Sayce1882, 267): ‘the figure is shockingly mutilated, the last damage to it having been occasioned by the smoke of a Yuruk's fire, whose tent was pitched against it when Mr. Spiegelthal visited the spot three of four years ago. It is however, a mere duplicate of the first’. Also, in Bittel (Reference Bittel1939, 182) we find the assertion that ‘The relief consists only of poor debris [… Most of the relief] is destroyed, torn, and probably was burst and chipped off by a Yuruk's fire’.Footnote 5 However, Kohlmeyer noted that this explanation is not convincing, because the block of the relief has a homogeneous patina (Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, 19). I can only subscribe to the doubts of Kohlmeyer because a fire would not have broken the top left of the block, but the bottom, directly under the fireplace. Moreover, it would require a surprisingly strong fire to break such a granite block (see Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, pls 6 and 7.3). The action of weathering since 1200 bce as well as erosion (in the case of the river flooding) are more probable factors, rather than the actions of ‘ignorant nomads’. Kohlmeyer seems to have been the last to have seen and drawn this relief in 1977, when the road was still dirty (‘not asphalted’: Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, 13, n. 49), but in 1982, Kohlmeyer noted that with the renewing of the road and the change of its course, the relief must be considered destroyed (Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, 19, section 3.2). The same is valid for the two adjacent inscriptions C1 and C2.Footnote 6 This means that official works to modernize the countryside are responsible for the main destruction of the relief of Karabel, not locals. It is difficult not to gain the impression that the first scholars took care and time to complain against ‘the ignorance’ of local people, and that the later archaeological communities ignore their own negligence as well as that of the state.

Damage to the main relief (A)

Concerning the main relief, Kohlmeyer noted that weathering processes were clearly visible by comparing the cast of 1874 and the condition in 1977, particularly at the horn of the cap and the left hand (Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, 16b). There is no detailed damage assessment, but in the last 50 years, that is after the destruction of relief B and inscriptions C1 and C2, the situation did quickly worsen. Elif Tulunay, in an unnoticed paper (Reference Tulunay2006, 24) notes ‘Mindless people searching for gold behind the stone [i.e. relief] drilled a hole into the relief so that dynamite could be inserted [and detonated]’.Footnote 7

Karabel is a pristine example of the interface of archaeology with the public, and may help to reflect better on the role of archaeologists. Karabel is not part of an archaeological project and therefore is not integrated in specific outreach activities or community work programmes, as we would expect from a current research project. Karabel is sufficiently ‘remote’ to be away from main touristic roads, especially as the region offers fabulous monumental remains (Ephesus, Pergamon, Miletus, Aphrodisias, Clazomenae, Teos or Sardis). In the framework of this article and without authorization, it was not possible to realize a survey to ask local people about their appreciation of Karabel, as has been done for UNESCO sites in Turkey (Apaydin Reference Apaydin2017; Reference Apaydin2018a,Reference Apaydin and Apaydinb). However, the Central Lydia Archaeological Survey project, working in the Region at the border of which Karabel sits, proposed a balanced reflection following the view of a looted place in a non-urban landscape (Kersel et al. Reference Kersel, Luke and Roosevelt2008; Roosevelt & Luke Reference Roosevelt and Luke2006). The project discovered the sculpture of a lion in a field, which was destroyed shortly after asking someone from the vicinity about the biography of the object. Consequently the authors ask in their paper if their intervention may have been the cause of the destruction: if, for example, the field owner feared that the place could be declared archaeological, leading to a set of restrictions or even expropriation (Roosevelt & Luke Reference Roosevelt and Luke2006, 191). Hatice Gonnet recollects a visit to Karabel with David Hawkins in 1984, when taking a meal before walking to the relief, the owner of the teahouse was afraid to let them visit ‘Hacibaba’ [a nickname for a spiritual leader, or colloquially an elderly respected person] because two communities of neighbouring villages were fighting for the right to dig up ‘the’ treasure (Gonnet Reference Gonnet and Singer2010, 97). There is a widespread belief that treasure, specifically gold, is hidden in old objects or places (Roosevelt & Luke Reference Roosevelt and Luke2006, 191). This is old folklore and ‘headlines’ in newspapers, mostly reporting on ‘sumptuous’ archaeological finds, are also in play (however, see Kocaaslan Reference Kocaaslan2019). This may well encourage the persistent widespread belief that it is possible to earn money from archaeological objects found during illegal digging, or to find a ‘gold treasure’, as depicted in Yilmaz Güney's famous 1970 film Umut [Hope]. The Central Lydia Archaeological Survey (CLAS) researching the involvement of local communities in looting gathered information about locals’ views. The researchers suggest that inhabitants from the surrounding villages were not necessarily aware of the rich history of places, but were eager to learn as ‘many are interested in the potential for treasure’ (Kersel et al. Reference Kersel, Luke and Roosevelt2008, 315). However, they point out that this is a consequence of the (monetary) value given to artefacts, which is based on the knowledge provided by the archaeologist themselves and incorporated into the market for such artefacts. The current social and economic contexts enable economical wealth to be assigned to cultural commons, a monetization exacerbated by the tourism industry.Footnote 8 To mitigate their role in sustaining networks of looting, the CLAS project suggests that archaeologists must change the way artefacts and monuments are perceived, starting with the message archaeologists are providing.

In 2019, new instances of damage were publicized and prompted a thoughtful public statement by the Istanbul branch of the Turkish Archaeologists Association (Arkeologlar Derneği Reference Arkeologlar Derneği2019). First, it put the destruction that happened at Karabel into a wider context of illegal but intense treasure-hunting activities in Turkey. The association of Turkish archaeologists stresses that the Turkish state has the responsibility by law to protect archaeological sites, including Karabel. Calling for hardening legal measures against treasure hunting, the public statement (Arkeologlar Derneği Reference Arkeologlar Derneği2019) rightly points to a solution of the problem in considering the Karabel monument as a living area associated with a holistic conservation management plan of the landscape. ‘Protecting this wealth is the common duty of academia, society and the state, and all parties must do their part in this regard’.Footnote 9 Indeed, the archaeology association opens its public statement with this call: ‘We should not remain spectators when a 3200-year-old monument is destroyed under our nose!’ (Arkeologlar Derneği Reference Arkeologlar Derneği2019).Footnote 10

‘Vandalizing’

The destructions and damage at Karabel do not only come from treasure-hunting activities, but the monument was also hammered with the aim of destroying the motif; it is even reported that acid has been thrown onto the relief. From my point of view, this clearly illustrates that local people have been forgotten in the life story of the monument by scholars and as such, can hardly be engaged with it. Monuments are placed in the public space, and by ‘design monuments should be affective and cathartic, yet both functions are contingent and frequently ephemeral; though built for the ages, they are commonly destroyed or neglected once their relevance is rejected or lost’ (McClellan Reference McClellan2000, 6). This is the area in which we find the limit of the homogeneous myth of Karabel resurrecting the Hittites. This story takes the monument as an occasion to tell a story about the past, but does not incorporate the question of how it should serve the local population in the present. As Holtorf puts it (Reference Holtorf2013, 16–17):

Traditional concepts of cultural heritage have focused on cultural monuments, often historic buildings and archaeological sites, taking for granted that remains of the past, as best understood by experts such as archaeologists, are inherently valuable and therefore deserve to be preserved for the benefit of future generations. […] In reality it is preserved for the present, as present-day social values and attitudes govern the way in which we define, manage and indeed construct heritage.

In this context, how should the damage at Karabel be assessed? Is it vandalism or iconoclasm? On the one hand, it is vandalism, but on the other hand, it can also be read as iconoclasm, as an action having another level of meaning. The ‘vandalism’ of the figure is done within a specific economic, social and political context. By interpreting this act as the consequence of global societal failures, it becomes iconoclasm. The act of iconoclasm signals not just that that commemorated is now forgotten; it continually reiterates that the forgotten are forgotten (Elsner Reference Elsner, Nelson and Olin2003). Clay (Reference Clay2012b) proposes that representations should be considered as signs that are decoded and interpreted by communities according to their backgrounds, beliefs and cultural experience. He stresses that ‘breaching the physical integrity’, i.e. altering the aspect of the representation by removing parts and adding others ‘ensured that the object could be made to point to new meanings legible in relation to contemporary discourses. Thus, acts of iconoclasm could be used to point to the dominance of particular discourses and to their sympathizers’ (Clay Reference Clay2012a, 277; cited in Spicer Reference Spicer2017, 1013; see also Groys Reference Groys, Latour and Weibel2002). Therefore, instead of accusing ignorance, iconoclasm is an occasion to re-evaluate and re-map the meaning of places: for example, explaining how the destruction at Karabel is also the consequence of economic and social struggles of people entangled in a neoliberal society. The damages are partly the consequences of exclusions taking place in world-wide and local politics; they are partly the results of policies calling for profits from every kind of resources—including ‘cultural resources’; they are partly the corollary of weak regulations against the destruction of commons; but they are also the fate of the absence of more inclusive messages from the archaeologically interested communities. The theoretical framework of landscape iconoclasm calls for studies showing this failure, and to mitigate it by providing new perspectives (González Zarandona Reference González Zarandona2015). New readings should offer alternative affordances to engage the site in the history of contemporary Turkey, the history of the Hittites and all the other histories in between and around, rooted in local or global scenarios. Writing about Karabel should also strive to incorporate new voices as well as placing destructions in relation to broader social contexts.

An example of diversifying perspectives with new sources

Computers and the internet have changed every aspect of how historians and archaeologists do their work, and arguably, how it is expected that they carry it out. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, availability of ‘primary’ sources through digital replicas is reviving historical scholarship. With the mass digitization of libraries and archives, an increasing number of sources are accessible online (Popkin Reference Popkin2016, 170–84). SALT Research curates an archive of digital sources on the built environment, social life and economic history with an emphasis on Turkey: https://saltresearch.org. Among other documents mentioning Karabel, a newspaper from Izmir published in 1961 shares memories about the monument (Fig. 11).

Figure 11. ‘We did not even stop in Kemalpaşa. Ten minutes later the cars turned to the right. We got off under an arch decorated with tiles, and we went to the “Hittite Father” rock relief. At this place, under the shadows of pine trees rising to the sky, art and nature unite. Here we listened to the Pasha's speech on history and art’ (trans. N. Strupler). (Recollection about Kazım Dirik, extract from Sadık Çiner, İmbat, July 1961, 6. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 − SALT Research Archive.)

The main narrative is a personal account about Kazım Dirik (1881–1941), who was governor of Izmir province from 1926 to 1935, right after the foundation of the Turkish Republic (Ünalp Reference Ünalp, Doğaner, İlgazi and Temel2020). As agent of Turkey's Early Republican ‘modernization’ programme, Kazım Dirik was active in public works such as the construction of roads, bridges, schools, cooperatives, banking services, fountains (Uçar Reference Uçar2014) and development of villages (Sezer Reference Sezer2019). Improving the road network was considered critical, and Kazım Dirik was highly praised from the government for this work. A citation from the Ministry of National Defence (dated 31 October 1927, no. 303/84I8) refers explicitly to the work done to renew the road of the Karabel pass (Dirik Reference Dirik2020). Over the road, close to the relief, he built an arch to signal the relief. This arch is briefly mentioned in footnotes of scholarly articles (such as Bittel Reference Bittel1939, n. 15; or Kohlmeyer Reference Kohlmeyer1983, n. 49). It has been reproduced only once (Ehringhaus & Starke Reference Ehringhaus and Starke2005, 90), even if this may have been a focal point in local histories, as Çiner's memoir suggests. Çiner's use of term Hitit Baba (‘Father Hittite’) is revealing of local esteem and respect as suggested by the nickname baba (father), echoing the ‘hacibaba’ mentioned by Gonnet (Reference Gonnet and Singer2010, 97). Hence, this tiny extract from a local newspaper echoes at least two other voices, local and official, each appreciating and defending the monument.

Re-wrapping: Karabel as a beauty in nature

In an imaginary world, now, at the end of the northern hemisphere summer of 2022 ce, a person visits the monument, and picks the following text among the multiple contextualizing signs:

Look around you

Close your eyes

Listen

Slowly breathe in, gently breathe out

Listen

Quietly breathe in and breathe out

…

My name is Tarkasnawa

I am the king of the land of Mira

I let it be written on the right side of my head with signs.

As you can see, I have been attacked many times while I am defenceless

It is painful, I wanted to remain eternally young

I am even more pained when I see how nature is mutilated

Here and elsewhere in the world

Nature is also defenceless…

I chose this place to have my portrait sculpted because I like coming here

The city is far away, the climate is pleasant

To spend the night in a tent or under the starry sky

The wind blows between the branches

You start to dream of another world

Nature is beautiful

I would like you to remember it.

This is an imaginary dialogue that King Tarkasnawa could have pronounced. Indeed, the inscription that is on the right of the head was successfully read in 1998, after more than 150 years of intense international cooperation to decipher this script and language. The inscription reveals that the person represented is Tarkasnawa, who declares himself to be the King of the land of Mira. Why a relief of Tarkasnawa was made here cannot be established. We have multiple, not necessarily exclusive explanations. Some people think that it was a sign to make public the border of the land of Mira. Others proposed that it was used to make his power more obvious. It is generally accepted that Tarkasnawa lived in the thirteenth century bce, that is, more than 3000 years ago. He was also represented on other objects, especially seals (a kind of stamp), showing that he was clearly looking to have his name and representation widely displayed and available. If social media had existed at that time, he would certainly have striven to be an influencer.

Undoubtedly, he was extraordinarily successful in this endeavour, not only because he is still present and because we could decipher his message, but also because Herodotus, a writer of the fifth century bce (born close to the modern city of Bodrum) describes this relief in his Histories. Herodotus thought that the relief represented a pharaoh, an Egyptian king, because he did not know of Tarkasnawa, and the signs utilized in the inscription (Luwian) bear some similarity to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. This influenced the European travellers who drew the relief in the nineteenth century ce, such as the Frenchman Charles Texier. He knew about Herodotus’ ideas and his drawing illustrates that he was deeply influenced by this preconception when he stood in front of the monument and drew it (Fig. 12). If you compare the drawing to the monument, what differences can you spot?

Figure 12. Drawing by Charles Texier. What are the differences from the relief? Do they relate to his artistic capacities? Did he have a preconception of what to see and what to stress when he stood here and drew the relief in 1839?

It took more than a century, numerous articles, books, visits here and in museums, drawings, photographs and international conferences to understand that Tarkasnawa was a contemporary of the Hittite royal family living in Hattusa. Starting from almost nothing, archaeologists and philologists had to decipher languages, carry out archaeological excavations, study artefacts, make mistakes, corrections and improvements. Each piece has been studied by different persons across time, and it continues today. Therefore, it is especially important to preserve artefacts such as this relief, so we can still make new discoveries by re-evaluating it, like you today, or someone else tomorrow!

We tend to associate one person with a discovery, but in fact, this never happens alone. At Karabel, the first travellers were guided by local people who already knew the relief. The first European travellers in their accounts describe vividly how they interacted with the local population at that time. For example, Henry John Van Lennep, an American born in Izmir in 1815, writes in his travelogue (Reference Van Lennep1870, 322): ‘At 2⋅10 our guides stopped under a tall pine, and pointing up hill to the left, told us that the object of our search lay in that direction among the trees and shrubs. We immediately began to ascend the steep hill side, amidst an abundant vegetation’. In 1940, Güterbock proceeded in the same manner to find the other relief B—and at that same moment spotted the inscriptions C1 and C2.

Sorry? What do you mean exactly? Are there other reliefs to discover?—Yes and no. Unfortunately, these reliefs were destroyed, when the road was asphalted, at the end of the 1970s. This is sad because some inscriptions could not be deciphered before that time. We cannot access them anymore and we could not find a consensus on the reading. The destroyed artefacts were sculpted close to the river, 100 m from here. There, a relief similar to a person (like Tarkasnawa) and two other inscriptions were carved next to it. The complete destruction shows what happens when we forget to care about monuments, and nothing can be done to bring them back.

It is a bitter irony that this happened with the asphalting of the road. Initially, immediately after the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Kazım Dirik was appointed governor of the region of Izmir. To offer better infrastructure and interconnections, he coordinated works to renew the road passing by Karabel. Moreover, he looked to build facilities for those visiting Karabel, with an arch over the road to signal the presence of the relief to everyone. In a journal from Izmir published in 1961, memories about Kazım Dirik include this passage (Çiner Reference Çiner1961):

We did not even stop in Kemalpaşa. Ten minutes later the cars turned to the right. We got off under an arch decorated with tiles, and we went to the ‘Hittite Father’ rock relief. At this place, under the shadows of pine trees rising to the sky, art and nature unite. Here we listened to the Pasha's speech on history and art.

Tarksnawa may have answered at that point:

Look around you

Close your eyes

Listen

Slowly breathe in, gently breathe out

Listen

Quietly breathe in and breathe out

…

My name is Tarkasnawa

I am the king of the land of Mira

Nature is beautiful

I would like you to remember it

I would like you to protect us.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Early.PostDoc Mobility Grant at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research in Cambridge, and I would like to thank these institutions for providing an ideal environment. For this paper, I am grateful to Toby C. Wilkinson for providing comments on a draft of this article, and to the anonymous reviewers. Christian Casey contributed with editing the English and provided insightful comments. Some of the ideas from this article have been presented at the conference Identities organized by TAG-Türkiye in 2021, for which proceedings I submitted a paper on inventing Karabel's identity.