Introduction

Preliminary work at the site of Qijiaping 齐家坪 in Guanghe 广河, Gansu甘肃, China, identified an area of concentrated geophysical anomalies in the southeastern part of the site (Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017). These anomalies were identified as ceramic kilns based on surface debris related to pottery production in the vicinity, the strength and concentration of magnetic anomalies, and selective coring. Excavation of three contiguous trenches at the location of one of the anomalies indeed revealed the outline of a kiln, and this feature was fully excavated during two seasons of fieldwork at the site conducted by the Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Harvard University. As the excavation proceeded, it became clear that the kiln did not match the expected size or structure of a kiln contemporary with the majority of cultural remains from the site, which mostly date to the Qijia Culture period (c. 2300–1500 bc) (Flad et al. Reference Flad, Zhou and Womack2021; Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017; Reference Womack, Wang, Zhou and Flad2019b; Reference Womack, Flad and Zhou2021; Reference Womack, Guo, Wang, Zhou and Flad2023). Instead, this feature was used to produce roof tiles, and as the data discussed below will show, it is probable that the kiln was constructed and used during the Song Dynasty period (960–1279 ad). The chronological and stylistic association with Song Dynasty material culture indicates a connection, whether direct or indirect, with the Northern Song (Beisong 北宋) occupation of this region.

When the kiln was decommissioned, the flues of the kiln chamber were filled with objects, including pottery fragments, animal bones and stones. Among the stones was a rock that was deliberately modified to be phallic-shaped. This item adds to the corpus of stone and clay objects in the form of male genitals and suggests a potential gendered aspect of the Song kiln at Qijiaping. Phallic objects are symbols that reference masculinity and fertility in a variety of ways in different cultural contexts. Identifying this stone phallus at Qijiaping contributes to our understanding of the way that masculinity may have played a role in Song military expansion.

Archaeological study of masculinity relates more broadly to the investigation of identity and the embodiment of gender through symbolism and material culture (Alberti Reference Alberti and Nelson2006; Ardren & Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006; Conkey Reference Conkey, Schiffer and Spector1984; Meskell Reference Meskell and Hodder2001; Voss Reference Voss and Nelson2006). Recognizing that aspects of identity, including gender, are not predetermined or fixed and have fluid boundaries, archaeologists since the 1980s have called attention to the importance of examining those social contexts within which gender is highlighted in order to grasp the way in which gender roles become inscribed (see contributions to Donald & Hurcome Reference Donald and Hurcombe2000; Gero & Conkey Reference Gero and Conkey1991; Hays-Gilpin & Whitley Reference Hays-Gilpin and Whitley1998; Kelly & Ardren Reference Kelly and Ardren2016; Linduff & Sun Reference Linduff and Sun2004; Nelson Reference Nelson2007; Nelson & Rosen-Ayalon Reference Nelson and Rosen-Ayalon2002; Schmidt & Voss Reference Schmidt and Voss2000; Sørenson Reference Sørensen2000; Wright Reference Wright1996). While particular attention has been focused on exposing gender biases, ‘finding’ women and ‘problematizing assumptions about gender and difference’ (Conkey & Gero Reference Conkey, Gero, Gero and Conkey1991, 5), it is also important that we find and mark activities that relate to the practices of male sexuality and gender demarcation in past contexts in order to challenge the assumption of male subjects as universal actors (Alberti Reference Alberti and Nelson2006). As Ardren and Hixson (Reference Ardren and Hixson2006, 7) have observed, ‘male sexuality in particular, has been defined narrowly as procreative, heterosexual, and utilitarian’, thus eschewing an attention to the ways in which symbols of the male sex, such as replica phallic symbols or artistic representations of male sexuality, might relate to other social practices and roles.

As we revisit in the discussion later in this paper, phallic symbols need not universally imply concepts of gender that reify a male/female binary, nor need they necessarily be understood through the lens of masculinity, but they do relate to the way in which attributes of biological sex are activated within social contexts that have gendered connotations. Kelly and Ardren (Reference Kelly and Ardren2016) have recently compiled a series of studies that highlight the variety of ways that gender is salient in contexts of craft production and manufacturing (see also Dobres Reference Dobres1995). These studies draw attention to the question of how the concept of gender was relevant to technological practice. Likewise, borderland contexts in areas of colonial encounters are rife with gendered disparities that can involve considerable gender imbalance in the populations that are interacting, often with devastating consequences for colonized populations (see, for example, Voss Reference Voss2008; Voss & Casella Reference Voss and Casella2012). As we will argue, manufacturing work and activities associated with militarized occupation in a borderland are two contexts relevant to the Qijiaping kiln example. These aspects of military and political culture in medieval China remain underexplored in previous research. The Qijiaping case study opens up discussions on the activation of gendered symbolism in ancient borderland contexts where military conflicts and political changes occurred.

Excavation background

The Tao River Archaeology Project (TRAP) has focused on tracing the nature of technology and technological change along the ‘proto-Silk Road’ in northwestern China, particularly in the Tao River valley, a tributary of the Yellow River in Gansu (Flad Reference Flad, Hein, Flad, Miller and Angeles2023; Flad et al. Reference Flad, Zhou and Womack2021; Jaffe et al. Reference Jaffe, Hein and Womack2021; Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017; Reference Womack, Horsley, Wang, Zhou and Flad2019a; Reference Womack, Flad and Zhou2021). This region and the cultural traditions fit into a spatial and chronological context that is rife with evidence of interesting technological developments that speak to a series of social transformations, such as long-distance interactions, developments in political organization, radical shifts in subsistence practices and the catalysis of changes that would profoundly affect the development of civilization across China and East Asia. The project aims to investigate more localized processes that provide finer spatial and chronological resolution to address the technological changes along the networks of the proto-Silk Road.

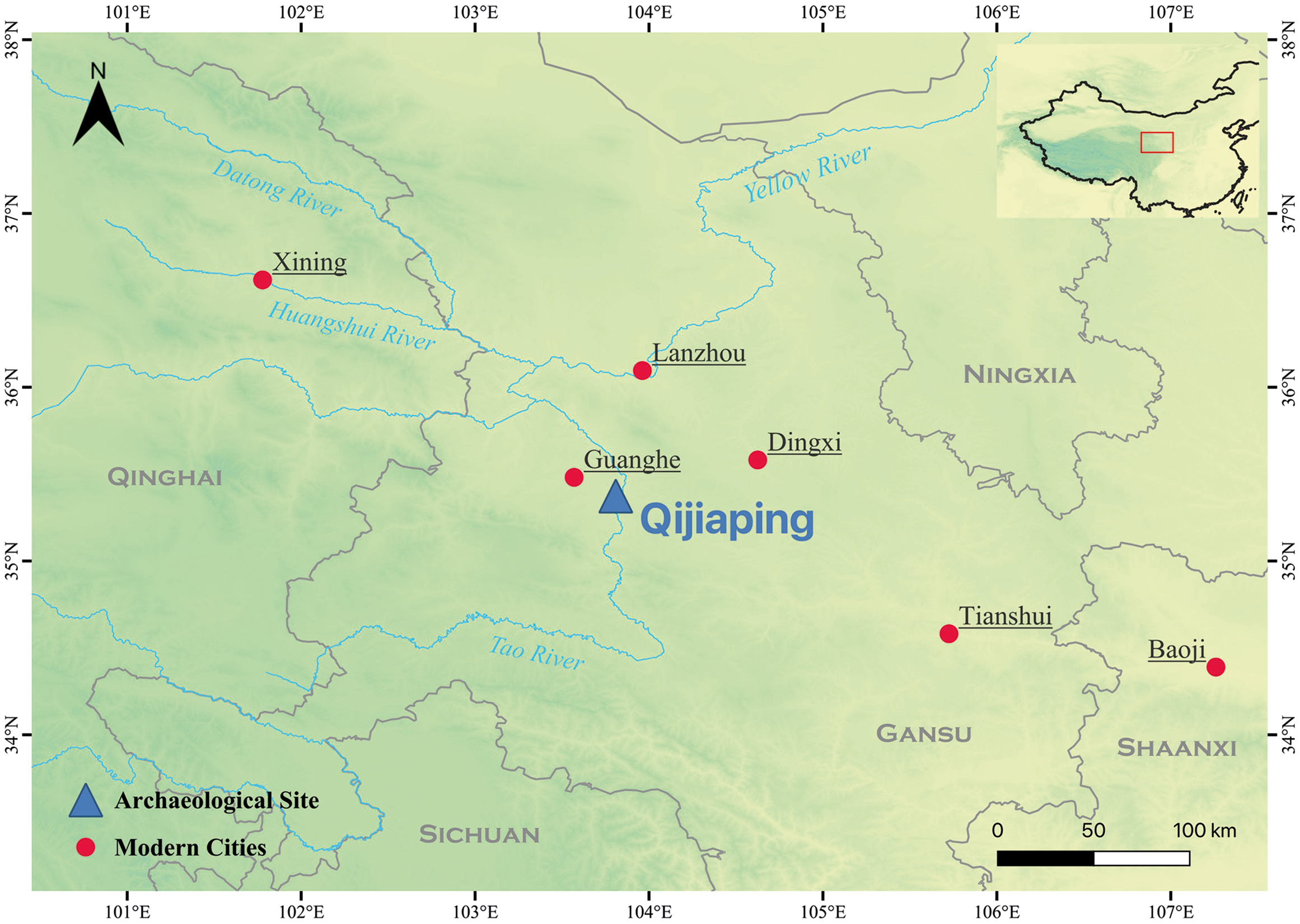

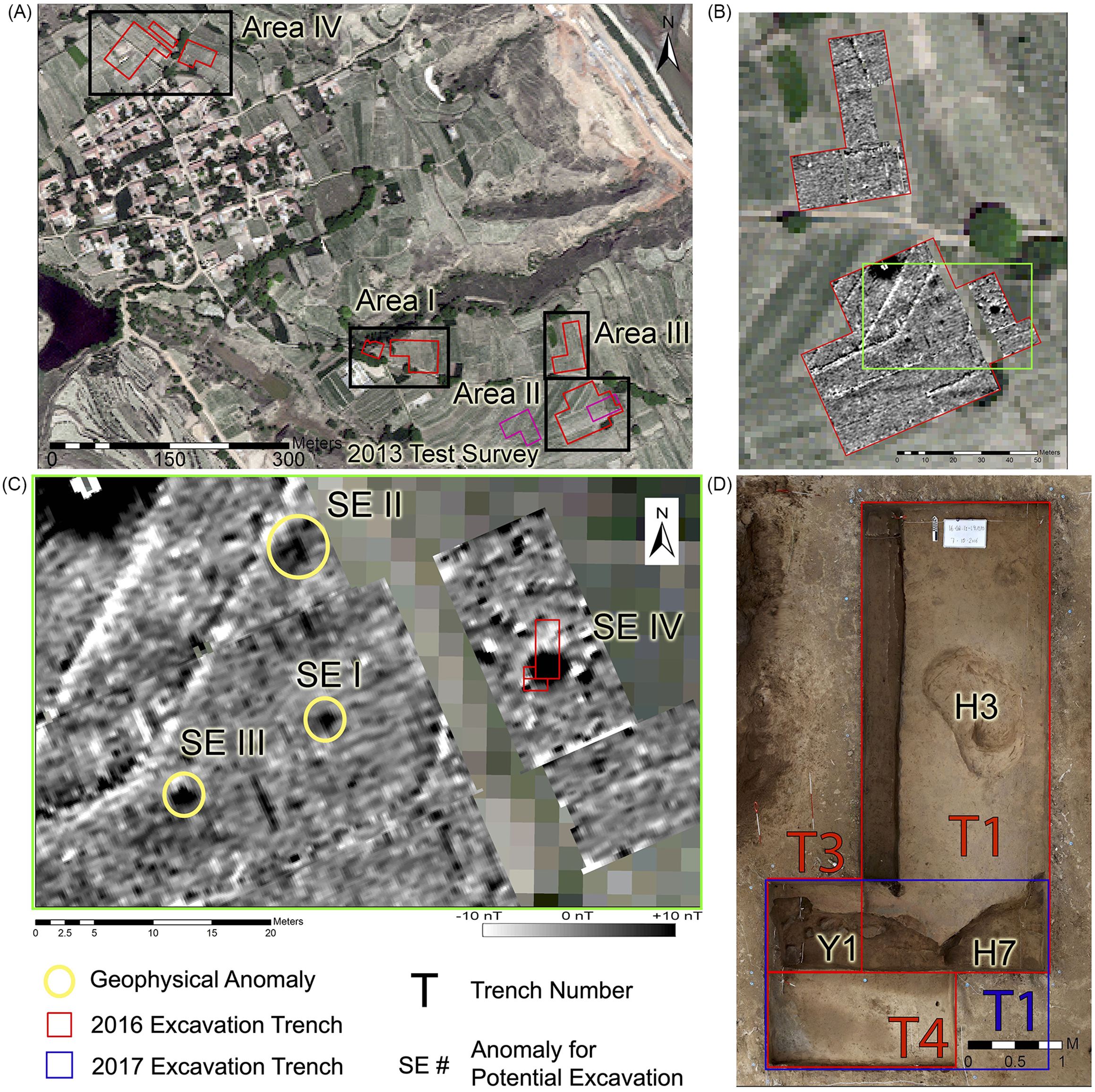

We chose Qijiaping (Fig. 1), the type-site of the Qijia Culture, as our starting point and have conducted fieldwork to understand the spatial organization of archaeological features at this site and others that reflect different aspects of the technology associated with the Qijia Culture (Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017). In 2013, we conducted geophysical survey that focused on areas where there was reason to believe we might identify sub-surface remains. The geophysics turned up some significant magnetic anomalies approximately +12 nT in strength in alignment at approximately 15 m intervals (Fig. 2A–C). We cored these anomalies with a bucket auger and recovered ash, burned clays and other evidence showing that burned material and other archaeological debris started around 60 cm below the surface and continued for around 2 m in depth. We expected these features to be a group of pottery kilns of the Qijia Culture that date to the second millennium bc.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Tao River and Qijiaping. (The map is produced in QGIS Version 3.40 LTR.)

Figure 2. (A) Areas of geophysical survey at Qijiaping; (B) closeup of magnetometry results from Areas II and III. Green outline shows area of focus in C; (C) anomalies identified for potential excavation, all similar in size and intensity to the example explored through excavation at SEIV; (D) Excavations at anomaly SEIV in 2016 (red trench outlines) and 2017 (blue trench outline). (After Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017, figs 7 & 8.)

To test this hypothesis and further examine this aspect of Qijia Culture pyrotechnology, we chose the anomaly in the southeast corner of our survey zone. Excavations began in July 2016 and involved the opening of a 2×5 m excavation trench (T1) (Fig. 2D). We positioned this trench to bisect the anomaly and thus allow us to examine a cross-section of the feature. We only know of a few published examples of kilns from Qijia Culture period contexts. Based on these examples, from the site of Lajia 喇家 in Minle 民和, Qinghai 青海 (Ren Reference Ren2015), and the site of Shatangbeiyuan 沙塘北塬 in Longde 隆德, Ningxia 宁夏 (Ningxia 2020), we anticipated that this kiln feature would be an updraft kiln with multiple central flues that would bring the heat from a lower firebox into an upper firing chamber and would be under 1 m in diameter. We excavated the unit with shovels and trowels and screened all sediment in a 5 mm screen. During excavation, as in all units in TRAP, we controlled excavation contexts using a ‘Locus’ system that allows us to control for both vertical and horizonal positions of finds. Each locus is described separately, and associated artifacts are grouped by material type into bags that are given ‘Field Catalog Numbers’ (FCN). Approximately 43 cm below the surface, we uncovered a strip of fired grey earth running from the west baulk of T1 in an arc towards the south baulk of the unit. Further excavations showed that the strip was part of the roof of a kiln feature (designated as Y1) of roughly 2×2 square metres. This scale far exceeds other known Qijia Culture period kilns, and structurally the kiln was very different from the known updraft kilns of the Qijia Culture. The kiln feature was cut on the eastern end by a shallow pit (H7) in the southeast corner of T1. To clarify the nature of Y1 further, we opened two additional excavation trenches to the south (T3 and T4). The collapsed roof of the kiln was exposed during the 2016 fieldwork season, and then in 2017 the excavation unit was reopened and the kiln was excavated in its entirety.

The kiln

As excavation proceeded further, it became clear that H7 was superimposed above a series of layers of fill deposited into a front chamber after the kiln was decommissioned and began to collapse and fill in. The layers of fill in this front chamber were designated as strata of ‘H4’ during excavation. After the kiln was abandoned, this area gradually filled up, and we divided the contents of this pit into 20 loci as our excavations proceeded. These loci can be combined into five distinct layers of materials distinguished as H4 Levels (1)–(5). These levels overlap in time with the fill that collapsed into the kiln chamber itself (Fig. 3). Once the contents of the kiln chamber and ‘H4’ were removed, the excavations revealed a mostly intact kiln chamber with three converging flues on the western wall (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Top plan, wall drawings and profile of kiln Y1 at Qijiaping. (A) West wall; (B) south wall; (C) top plan; (D) east profile.

Figure 4. Photo-composite 3D model created with Agisoft Photoscan of kiln Y1 after the excavation of the final locus of material from within the flues in June 2017.

The kiln consists of a main chamber (the kiln chamber), an operation room (the front chamber), three flues and flame paths. The total length of the kiln is approximately 4.5 m. The main chamber is about 2.8 m in length and 1.6–1.8 m in width. Tool marks on the interior wall of the kiln chamber indicate that this facility was carved out of the loess hillside (Fig. 5A). Once it started to be used, the walls of the kiln then hardened and changed colour. Flue channels were also carved, and then covered over with patches of clay in order to control the dispersal of heat (Fig. 5B). On the bottom of the main chamber, just outside the central flue, are flat ceramic tiles forming a sort of pavement (Fig. 6). We found other examples of complete and defective ceramic tiles in both the main chamber and the operation room (Fig. 7).

Figure 5. (A) Tool marks on the interior of the south wall of kiln Y1; (B) clay patch on west wall of Y1 covering central flue.

Figure 6. Tiles lining the base of kiln Y1 outside the central flue.

Figure 7. Tile fragments including a misfired tile sherd found within kiln Y1 in the main chamber (FCN 4281).

Although these examples provide ample evidence that tile making may have been a primary function of the kiln as a production facility, their position in the fill makes the precise association with the chronology of the kiln use more ambiguous. However, one context provides a stronger connection to a moment in the life of the kiln itself. Inside the flues we found a series of objects, including pottery, animal bones and stones.

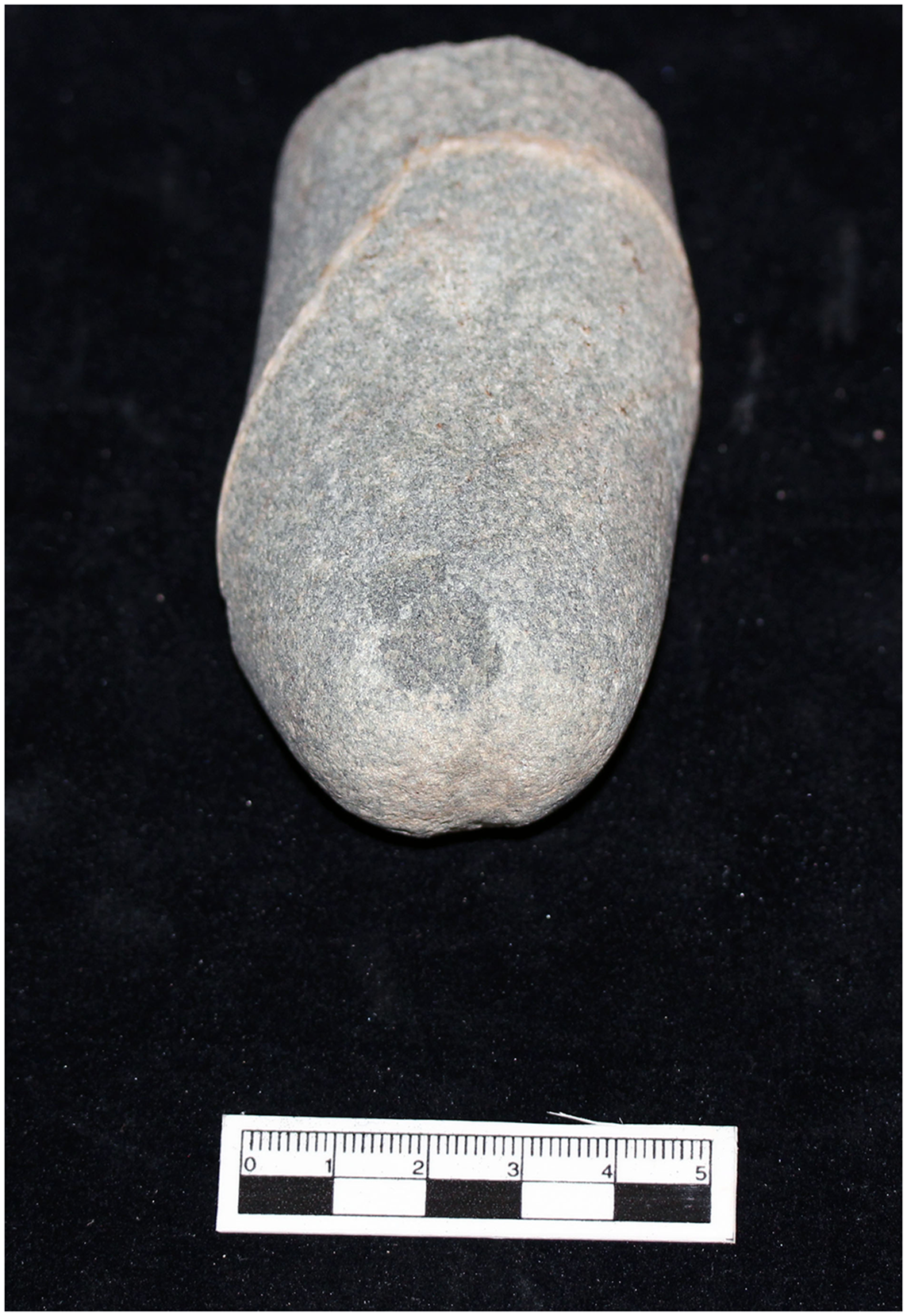

In the north flue, we recovered a total of three stone objects as part of Locus 43. These include two unmodified rocks, one of which is a black gabbro cobble and a second a brown quartz sandstone rock. The third stone object was a complete granite hammer measuring 17.4×6×5.4 cm and weighing 1106 g (Fig. 8). Excavation of the south flue recovered objects as part of Locus 46. These included one animal bone, one stone and two ceramic fragments. The bone was a left cattle scapula fragment. The stone was an unmodified slate or schist rock. The ceramic fragments were both grey tile fragments with cloth impressions (see Figure 9).

Figure 8. Stone objects from the north flue of kiln Y1 (FCN 4882). The stone hammer is in the middle.

Figure 9. Tile fragments discovered in the south flue of kiln Y1 (FCN4892).

Finally, inside the central flue was a group of animal bones, pottery sherds and stones in Locus 44. The pottery in the central flue consisted of 23 ceramic fragments. Six of these were grey tile fragments with cloth impressions. Six vessel sherds come from objects that are similar to the ubiquitous Qijia Culture material at the site. The rest of the pottery is historic-period pottery of various sorts, some of which were glazed (Fig. 10). The stone objects found in the central flue include seven unmodified rocks and cobbles. Four were sandstone, two gabbro or sandstone, one a quartz sandstone rock fragment and one a schist or slate rock. Some were quite large, the heaviest weighing 4425 g. In addition, a modified gabbro phallic-shaped stone (FCN4889) from this context will be discussed further below. The 17 animal bones found in the central flue include elements from horse, cattle, other mammal taxa and mollusc (Fig. 11).

Figure 10. Ceramics from the central flue of kiln Y1. (A) ceramics FCN 4887; (B) ceramics from FCN 4888.

Figure 11. Stone objects and animal bones from the central flue of kiln Y1 (FCNs 4889, 4890, 4893, 4894, 4895).

Faunal remains

The faunal remains in the flues of kiln Y1 are part of a collection of 609 animal bones collected from the excavations of units T1, T3 and T4 at Qijiaping. The number of identified specimens (NISP) and minimum number of individuals (MNI) for each taxon are listed in the Supplementary material (supplementary Table S1). The total NISP for all excavation units was 201, with the rest of 408 specimens that could only be identified to broad taxonomic categories such as ‘medium mammal’ or ‘mammal’.

Observations about the overall collection include several key points. First, domestic mammals represent the most commonly identified taxa. These include dogs (Canis familiaris), pigs (Sus sp.), sheep (Ovis aries), cattle (Bos taurus and Bos sp.) and horses (Equus sp.). The pigs were likely domesticated pigs, but it is possible that wild boar was also present in the assemblage. While some cattle specimens could be identified as taurine cattle (Bos taurus), other fragments were only identified to the Bos genus and could be taurine cattle, indicine cattle, yak, or wild cattle. The equids were only identified to the Equus genus, but it is likely that most of the equids were domestic horses and not donkeys due to the size of the bones. Pigs, sheep, cattle and horses occur in similar frequencies in both the NISP and MNI counts. However, the assemblage is not large enough to make definitive claims about the relative proportions of each type of animal domesticate. Second, wild mammal specimens are limited to one medium-sized deer scapula and rodents. Some of the rodent teeth look similar to mice (Micromys sp.) and others look similar to voles (Microtus sp.). The rodent bones do not have cut marks or burning visible on the surface. There is no sign that these animals were consumed by humans; these bones may be intrusive. Third, the collection contains non-mammals, including several small bird bones, frog bones, one mollusc shell and many small gastropod shells. The bird bones were very small, probably from a sparrow-sized bird. The frog bones all seem to belong to the same individual. The mollusc shell was a broken ornament made from a thick, white bivalve shell. This object is discussed in greater detail in the section on worked bone objects. The gastropod snails are commonly found in loess deposits in the region and were probably not consumed. Finally, there were several human remains in the assemblage.

Taphonomically, over 70 per cent of fragments in the assemblage were under 3 mm in length (supplementary Table S2), and a handful of bones had evidence of carnivore chew marks on the surface. No bones were carnivore digested and no bones had rodent chew marks on the surface (supplementary Table S3). Only 29 bones were burned.

Three worked bone artifacts were identified in the assemblage (supplementary Table S4). The shell ornament (FCN 4894) was found in the central flue of the kiln along with several other objects including eight of the taurine cattle bones (a carpal, metatarsal and phalanges from an articulating hoof), an equid pelvis fragment, an equid femur fragment, a large mammal rib fragment, a large mammal thoracic vertebra fragment and two unidentified mammal bone fragments.

The cattle, horse bones and shell ornament are part of the collection of objects that were inserted into the flues at the time when the kiln was decommissioned, and they can help us establish the date of the feature and further examine its significance.

Dating the kiln and its historical significance

We were first able to produce a hypothesis about the chronology of the kiln based on fragments of two white porcelain fragments (Fig. 12). The two fragments were found in the second layer of the deposits that filled the operation room of the kiln, more than 1 m below the surface, and have a glaze style common in the Northern Song and Jin 金 periods (c. tenth–thirteenth century ad). These objects were our first evidence that the kiln may correspond to approximately this date.

Figure 12. Ceramics from Locus 19 (FCN4268) including two fragments of Song porcelain.

When the kiln roof was first uncovered, we sent wall fragments of the kiln for TL (thermo-luminescence) dating at Peking University. The estimated date based on a sample of burnt clay was 830±80 ad. The result from this one date suggests that the kiln was fired contemporary with the late stage of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 ad). Although we do not have tremendous confidence in this TL date, its early date relative to the other evidence here does introduce the possibility that the initial construction of the kiln pre-dates the Song era. One of the taurine cattle phalanges from the central flue of the kiln was sent for radiocarbon dating at Peking University, which produced a result that situates the calibrated date between 1164 and 1257 ad (Table 1).

Table 1. The radiocarbon dating result.

The Qijiaping kiln shows similarity with one of the tile kilns (Y12) excavated in 2012 at the site of Xinjiekou 新街口in Luoyang洛阳, Henan河南 (Luoyang 2015). Y12 has a kiln chamber approximately 1.5 m long and 1.5 m wide, similar in size to the kiln at Qijiaping. Furthermore, there is a strong structural similarity in the way that the three flue channels that bring heat through the chamber come together (see Figure 13). The kilns uncovered at Xinjiekou date to the period between early Tang and early Northern Song (c. seventh–eleventh century ad). Y12, the most similar in size and structure to the kiln at Qijiaping, dates to the later phase of the kiln activity, which the authors place at the late Tang to early Northern Song period (c. ninth–eleventh century ad), thus similar to the date we have for the white porcelain fragments. The Xinjiekou kilns were likely part of a state-run kiln workshop that supported the reconstruction and maintenance of governmental buildings in Luoyang (Luoyang 2015).

Figure 13. The west wall of kiln Y1 at Qijiaping (left) compared with the flue wall of the Northern Song kiln at Xinjiekou in Luoyang (right). (After Luoyang 2015, 29, fig. 15.)

Overall, while it is possible that the kiln construction date is as early as the ninth or tenth century ad, evidence from the central flue and from the kiln structure provides a stronger argument for the end of the kiln-use dating to the twelfth century ad. Combining different lines of evidence, we infer that the kiln at Qijiaping should likewise be a tile kiln that broadly dates to the same era of late Tang or early Northern Song.

By 1111 ad, the location of Qijiaping was in a region within the boundaries of the Northern Song territory. This area was not part of the Northern Song territory until a series of military actions, known as the ‘Xihe Expansion’ (Xihe Kaibian 熙河开边), succeeded in the eleventh century ad (Forage Reference Forage1991; M. Liu Reference Liu2008), incorporating the present-day Lintao 临洮 area (known as the Xizhou Prefecture 熙州 during the Northern Song period) area in 1072 ad. This process of aggressive expansion occurred during the reign of Emperor Shenzong 宋神宗 (r. 1068–1085 ad) who was intent on reestablishing control over regions previously controlled by the Han (202 bc–ad 220) and Tang (Forage Reference Forage1991; von Glahn Reference von Glahn1987). The ultimate goal of Emperor Shenzong was to consolidate control over an area that would permit a successful defeat of the Western Xia (Xixia 西夏) (1038–1227 ad), centred in the present-day Ningxia region but with control of territory all the way to the Lanzhou area.

Between 762 and 1072 ad, the area south of the present-day Lanzhou 兰州, including the Tao River valley, was controlled by a confederation of Tibetan groups, known as the Qingtang Qiang 青唐羌, who occupied eastern Qinghai and southern Gansu (Forage Reference Forage1991; M. Liu Reference Liu2008). The death of the confederacy leader named Gusiluo 唃厮啰 in 1065 ad triggered disunity, which the Northern Song Grand Councillor Wang Anshi 王安石 (1021–1086 ad) took advantage of by sending Wang Shao 王韶 (1030–1081 ad) to attack the region. This strategic expansion was an important step in solidifying the stability of the northwest border in advance of an effort to defeat the Western Xia, which had a profound impact on the history of the Northern Song and the society and economy of the region.

In July of 1072 ad, Wang Shao captured and fortified Wusheng 武胜 and changed the Wusheng Garrison (Wushengjun 武胜军) to the Zhentao Garrison (Zhentaojun 镇洮军). In December, the Zhentao Garrison was promoted to the Xizhou Prefecture, and eventually Lintao became the administrative seat of the broader occupied area of the Xihe Circuit (Xihelu 熙河路), which included the adjacent prefectures of Hezhou 河州, Taozhou 洮州, Minzhou 岷州, and other places, all of which were associated with the Tao River valley. Since January 1073 ad, the Northern Song government started to construct fortresses and bulwarks to reinforce the regional defence. Several historical records in the History of Song (Song shi 宋史) and the Extended Continuation to Zizhi Tongjian (Xu zizhi tongjian changbian 续资治通鉴长编) attest to this construction, for example:

In January 1073 ad, ‘[The emperor] announced that one thousand soldiers from the Jingxi Circuit and two thousand soldiers from the Yongxing and Qinfeng circuits were sent to construct fortresses and bulwarks at the Nanguan and Beiguan passes and in other locations.’ (T. Li Reference Li2004a)

熙宁五年十二月,‘詔京西路差廂軍一千人,永興、秦鳳等路二千人,修築熙州南、北關及諸堡寨。’

In May 1075 ad, ‘[Zheng Minxian] suggested that channels and weirs were constructed from south of the Nanguan Pass in Xizhou for the diversion of the Tao River, and directed the water northward to the Beiguan Pass along the Dongshan Mountain, and irrigated the fields from the Shuyang Stockade in the Tongyuan Garrison. [Zheng Minxian] requested to recruit workers to start the construction.’ (T. Li Reference Li2004b)

熙宁八年闰四月,‘於熙州南關以南開渠堰引洮水,並東山直北通流下至北關,並自通遠軍熟羊寨導渭河至軍灌田,乞募夫開修。’

In January 1076 ad, ‘more than 268,000 workers were involved in moat construction in the Xihe Circuit, more than 62,000 workers were involved in the construction of the two fortresses of Dongsu and Wumugu, respectively, and more than 149,000 workers were involved in the construction of the Beiguan Pass …’ (Li Reference Li2004c)

熙宁八年十二月, ‘熙河開壕用二十六萬八千餘工,及修棟梀、五牟谷二堡各六萬二千餘工,北關堡十四萬九千餘工 …’

We see mention in these examples of the fortification at the Beiguan Pass 北关, which was situated quite close to the location of Qijiaping. Although Qijiaping is administratively located in Guanghe, it is closer to Lintao. Considering the excavation and previous survey results, including the cluster of other magnetic anomalies in the vicinity of Y1 that likely represent similar features, we argue that this was the location of a Song Dynasty tile kiln workshop. This group of ceramic kilns could have provided materials for the construction and maintenance of fortifications and bulwarks along the Tao River.

Tackett (Reference Tackett2008, 133) describes how Northern Song border policies attempted to construct a more clearly delineated border that were not reliant on isolated garrison towns. In some places, this involved enhancing or taking advantage of the presence of territorial border walls, which divided the Chinese and northern nomadic groups both physically and conceptually. Tackett argues that during this era ‘Military circumstances as well as the practical needs of the Song centralization project necessitated both the “linearization” of the border—that is, the reformulation of the border as a definitive line (at times demarcated by the Great Wall)—and the elimination of frontier marginal zones of ambiguous political control’ (2008, 103). There was a broader effort at wall building, renovation, and negotiation in many border regions of the Northern Song, particularly in areas contested with the Liao 辽 (916–1125 ad) polity in the northeast. In such contexts, places like the Tao River valley were locations of colonial infrastructure development beyond the construction of walls alone. It is true that there is a ‘great wall’ segment in the Lintao area, said to date to the period of Qin 秦 control starting in the Warring States 战国 era (476–221 bc) (He Reference He1987), and it is likely that the wall, like other remnants from earlier eras in the Song borderlands, would have been identifiable in the Song period as well and mentioned in historical texts (Tackett Reference Tackett2008, 117). That said, the Song references and the nature of the Song expansion to the region were not focused on establishing and reinforcing a border in this particular location, but rather supporting a process of further expansion for incorporating more territory, population and resources into the Song (von Glahn Reference von Glahn1987).

Discussion

In addition to the animal bones, pottery sherds and unmodified stone cobbles in the central flue, one stone object was a river cobble naturally formed in the shape of a phallus that was modified to accentuate this similarity (Fig. 14). The object is a gabbro cobble with a visible vein of quartz. The natural vein in the rock was used to form the glans, and the tip of the stone was also modified to form a groove (Fig. 15). The phallic form of this object serves as a point of departure to discuss the relationship between activities at this kiln and symbols of male genitals.

Figure 14. Verso and recto photographs of the phallic rock from FCN4889.

Figure 15. Modification of the tip of the phallic stone.

Archaeologically documented representations of phalli have emerged in a wide variety of contexts around the world. A recent example purporting to be the oldest such representation was discovered in an Upper Palaeolithic context at Tolbor-21 in Mongolia (Rigaud et al. Reference Rigaud, Rybin and Khatsenovich2023). Dating to 42,000 years ago, this unique pendant suggests a form of symbolic behaviour that employed reference to sexed anatomical attributes as personal ornamentation. Although this is the earliest known example, there are many other phallus representations that are known from past contexts, and these have evoked a wide range of interpretations. Some other Pleistocene examples associated with the Gravettian culture (c. 33,000–21,000 bp) are understood to reflect an awareness of the biology of reproduction (Conard & Kieselbach Reference Conard and Kieselback2006). Other objects that emphasize attributes associated with biological sex are interpreted to reflect concern with fertility, magic, eroticism and protection (see Bolger Reference Bolger1996; Johns Reference Johns1982). Another recent set of finds from Neolithic Anatolia contains narrative scenes that include both figures with prominent phalli and stand-alone phallic objects reflecting an importance of this feature to the construction of social relations in the context of a transforming social world during a period of transition to sedentism (Özdoğan Reference Özdoğan2022). Bronze Age Crete saw the creation of sanctuaries that include phallic symbols (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1992) that might reflect the mobilization of masculinity as a category (Alberti Reference Alberti and Nelson2006). Later contexts associated with the Roman world contain numerous examples of phallic symbols. A recently published example from Vindolanda in northern Britain is the wooden phallus to be recognized (Collins & Sands Reference Collins and Sands2023), adding to the more numerous metal, ceramic and stone phalli from other Roman contexts (Collins Reference Collins, Iveleva and Collins2020; Neilson Reference Neilson2002; Parker 2015; Reference Parker and Parker2017; Whitmore Reference Whitmore, Parker and McKie2018). Roman metal amulets that combine a fist with a phallus are often interpreted as masculine devices due to their association with military contexts, although they seem to have functioned additionally in some cases as apotropaic objects for the protection of children and as fertility symbols (Parker Reference Parker2015). Association with notions of masculinity is not limited to the Roman context by any means. Phallic depictions from contexts associated with the ancient Maya also reflect an emphasis on depictions of masculine sexuality that both conveyed and enhanced masculine concepts within Maya society (Ardren & Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006). In Maya art, depiction of phalli related to practices of penis perforation as powerful forms of ritual sacrifice that male leaders used to demonstrate power within the context of that particular ancient state.

Phallic symbols in Asia likewise occur in a wide range of contexts with varying symbolic significance. Among the earliest examples are stone and ceramic phallic objects associated with the Neolithic sites in north China, including the unearthing by J.G. Andersson of two examples from the Yangshao 仰韶 site in Henan during some of the earliest work on Neolithic archaeology in China (Andersson 1943; Reference Andersson1947). Zhang (Reference Zhang1986, 424–5) has suggested that the objects from the early Yangshao 仰韶 Culture (c. 6800–5600 bp) sites of Fulinbao 福临堡 and Quanhucun 泉护村 reflect the emergence of an androcentric ideal that emphasized symbols of maleness. Other Neolithic examples coming from sites such as Shuangdun 双墩 (c. 6000–3500 bc) in Anhui 安徽 (see Chen Reference Chen2016) and Chengtoushan 城头山 (c. 4400–3300 bc) in Hunan 湖南 (see L. Liu et al. Reference Liu, Zhou and Wang2022) have been argued by some to be phallic forms. Stone and ceramic phallic objects have been recovered from prehistoric contexts across China, and generally they are discussed as having an ambiguous association with fertility and the worship of male ancestors (e.g. K. Li Reference Li2003; Song Reference Song1983). Likewise, wooden phallus-posts, along with the vulva-posts that reflect an emphasis on female genitals, uncovered at the Xiaohe 小河 and Gumugou 古墓沟 cemeteries in the Tarim Basin 塔里木盆地 of Xinjiang 新疆 (c. 2000–1500 bc) are taken to indicate evidence of fertility worship in the Bronze Age settlements of this region (Wang Reference Wang2004). Phallic objects continue to be present in various forms into the later parts of the Bronze Age and beyond (see van Gulik Reference van Gulik1961). Among the most famous may be the V-shaped double-phallus bronze objects excavated from the tomb of Liu Sheng 刘胜 (d. 113 bc), the Han Dynasty Prince of Zhongshan 中山王 (Zhongguo and Hebei 1980). Similarly, in 2011, archaeologists excavated two bronze phalluses in the gallery of Tomb 1 at Dayunshan 大云山, attributed to a Prince of Jiangdu 江都王 named Liu Fei 刘非 (d. 127 bc; Nanjing & Xuyi 2013). These objects are associated with the active sexual pursuits of aristocrats like Liu Sheng and thus they are understood not to reflect a generic magical, apotropaic or fertility function, but rather to reflect particular sexual mores associated with the Han aristocracy. Phallic symbols of later historical period, albeit rare in the archaeological record, have been discovered. For example, one complete and several fragments of porcelain phalluses were found in a Song period burial in central Shaanxi (Yang Reference Yang1984). Similar porcelain phalluses were also unearthed from the Yaozhou Kiln 耀州窑 in the region nearby (Xiao Reference Xiao2002). Clearly phallic iconography in the historical era remained multifaceted.

A potential relationship between a phallic symbol and militarism in the Song case should not be assumed to reflect a universal association between military activity and gendered male identity. Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2021) has recently examined the association between masculinity and warfare broadly. He highlights the wide variability of social contexts within which warfare has emerged and the various ways in which this can be gendered. As Linduff and Rubinson (Reference Linduff and Rubinson2008) and their colleagues point out, not all warriors may be male. Likewise, as Alberti (Reference Alberti and Nelson2006) discusses in his overview of archaeology and masculinity, not all notions of masculinity are tied to aggression. As he points out, it is a mistake to equate evidence of a connection between them to a generalized masculinity that is applicable in all contexts, in part because an over-emphasis on men and violence has privileged certain understandings. Nevertheless, Ferguson points to the ways in which socialization often results in the gendering of conflict and killing to be associated with maleness.

Returning to the Qijiaping case, we see the deposition of a phallic object in a manufacturing context associated with expansion and military occupation. We assume that the use of this phallic stone as sexual symbolism in a context of architectural ceramic production is possibly related to a pursuit of masculinity, a concept usually referring to the actions and values habitually associated with males. Armed violent confrontations like wars or activities directly related to warfare may have been significant aspects of masculine social identity in medieval China. If we look into the political and military context of our project area during the early Northern Song period, we see constant warfare and political manoeuvring between Northern Song and its neighbours. In this context, the object poses the question as to whether there are gendered aspects of this military context that are being materialized within the context of architectural craft production. The pursuit of masculinity may have been tied to attempts to ensure successful ceramic production during war time and eventual military success. It was possible that this effort was pursued symbolically by the kiln operators through the use of gendered objects or sexual symbolism in certain steps of ceramic production.

Nevertheless, there remains a scarcity of archaeological evidence and historical records directly linking masculinity to warfare in the Song context. In excavated Northern Song period burials elsewhere in Gansu there is no clear evidence of heightened sense of martial activities. The mural paintings and brick carvings from the burials primarily depict themes on everyday life, ritual practices, filial piety and religious beliefs. However, it is important to note that most of these Northern Song burials are located east of the present-day Guanghe and Lintao regions, areas that were already under Song control before the Xihe Expansion in the eleventh century ad.

Despite the limited archaeological evidence and historical records directly linking warfare and masculinity, historical records do document the worship of kiln gods during the Northern Song period (Y. Liu 1997; Reference Liu2010). For example, one of the most frequently cited pieces of evidence is the ‘Stele of the Marquis Deying’ 德应侯碑, which was discovered in Tongchuan 铜川, Shaanxi 陕西, where the aforementioned porcelain phallus-associated Yaozhou Kiln was located. According to its inscription, the stele was erected in 1084 ad, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong. In this region, the imaginary earth and mountain deities had been venerated by local potters for their role in protecting clay acquisition and ceramic production. During the Xining period (1068–1077 ad), Master Yan, a Secretary of the Board, served as the governor of Huayuan Prefecture. The following year, with peace prevailing and governance running smoothly, Master Yan submitted a petition to honour these local earth and mountain deities, granting them the title of ‘Marquis of Deying’ (‘熙宁中,尚书郎阎公作守华原郡,粤明年,时和政通,奏土、山神,封德应侯。’) (Fu Reference Fu1983). The kiln god, ‘Marquis of Deying’, is a personification of the earth and mountains. The stone phallus found in the Qijiaping kiln may thus have represented a traditional form of the earth deity or an earth god and symbolized certain gendered aspects of craft production, in this case in a militarized context.

Conclusion

The tile-manufacturing kiln discovered at Qijiaping was unexpected. Most archaeological remains at the site date to the late prehistoric period and are associated with the Qijia Culture (Womack et al. Reference Womack, Jaffe and Hung2017). After demonstrating that the kiln dates, in fact, to a much later period of activity at the site, we determined that the most likely date of kiln construction is at the end of the Tang Dynasty or beginning of the Song Dynasty period, and that the kiln was likely used through the period of military occupation of the region during the Northern Song expansion in the area. At the time the kiln fell out of use, it was intentionally decommissioned, and artifacts interred at the time include a stone phallus, evoking a significant aspect of masculine gendered symbolism in the context of this kiln. This sort of gender symbolism is not widespread in similar contexts, but evokes a concern with aspects of craft production, medieval military and political culture in China that has been underexplored in previous research. Future work on the archaeology and history in borderland contexts of medieval China should pay attention to the degree to which gendered symbolism is activated in spaces and places of military conflict.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data can be found in Tables S1, S2, S3 and S4 at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095977432510005X

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was presented at the Society for American Archaeology annual meeting in 2018 in the session ‘What’s Hot in Pyrotechnology? Controlling Fire from Campfires to Craftspeople’ in Washington (DC), and again at the Society for East Asian Archaeology in Nanjing, China, that same year. We appreciate the assistance of all the colleagues and local community members who assisted with the excavations at Qijiaping during 2016 and 2017 when this kiln was recovered, including Ling-yu Hung, Jada Ko, Yitzchak Jaffe, Yanxi Wang, Anke Hein, Jaclyn Li, Rongzhen Guo, Xiuwen Zheng, Xin Su and Eric Carlucci. Xin Su analysed the stone artifacts and identified the stone raw materials. In addition, we received useful feedback and leads from several people at various stages of the composition of this manuscript, including David Sena, Matthew Sommer, Jeffery Moser, Jeehee Hong, Peter Bol, Poul Smith, Nicholas Tackett, Xiying Xie and Penghao Sun. We appreciate their help, but of course, these individuals do not bear responsibilities for the misunderstandings we may include.