Introduction

While artefacts have object biographies, landscape is perhaps unique in its accretion of complexity in ways which remain archaeologically visible. In this paper, we want to consider these biographical episodes from a temporal perspective, emphasizing that new features and changes to a landscape resulted from projects for the future. We consider that meaning in landscape is always temporal and inhabiting a landscape necessitates engaging with past, present and future. Any research focus on the temporality of landscape related to social significance and experience tends to prioritize the ‘past in the past’, probably because of the way that archaeologists often view the remains of the past as completed actions, which presents a theoretical difficulty in seeing the past future as full of possibility (cf. Adam Reference Adam2009; Barbalet Reference Barbalet1997, 118). Past and future are entwined in the course of action (Gosden Reference Gosden1994, 15–17), however, and we can nuance and strengthen our interpretations of past agency through a consideration of the different ways that people negotiated their relationships to the past and crafted their hopes, fears and aspirations into plans for the future. The material manifestations of the past in the past exist for archaeologists to interpret, but reconstructing the future in the past presents some challenges. Social theorists, anthropologists, philosophers and historians have demonstrated that the past, present and future are inextricably linked, but identifying the future through archaeological remains is a complex matter where uncertainty is unavoidable. Nonetheless, if we reorientate the concern with continuity, repetition of actions, transformation of meanings and other temporally contingent phenomena to try to understand how people were constructing their futures, we can expand and enhance our interpretations of the temporal facets of landscape.

Archaeologists relatively belatedly began to think around one of the key dimensions of their discipline, with time-concepts only beginning to be seriously debated in the 1980s (e.g. Shanks & Tilley Reference Shanks and Tilley1987a,Reference Shanks and Tilleyb; cf. Holdaway & Wandsnider Reference Holdaway, Wandsnider, Holdaway and Wandsnider2008; Lucas Reference Lucas2005). Time is now accepted as socially constructed and interpreting past ideas of time has become a key theme in archaeology. Multiple time-scales can exist in a single society and the significance of cycles, rhythms, origins, events, horizons and other phenomena have been addressed in the last 30 years. Orientations to the future movements of the moon, sun and planets, as well as to the human life-cycle, have received particular attention and been established as socially significant in a number of, mostly prehistoric, contexts (e.g. Gardner Reference Gardner2012; Lucas Reference Lucas2005; Murray Reference Murray and Murray1999; Olivier Reference Olivier and Murray1999). There has also been considerable debate over the most appropriate time-scales for archaeologists to work with (e.g. Bailey Reference Bailey2007; Harding Reference Harding2005). Once established, a central topic in the archaeology of temporality became ‘the past in the past’. Social memory, commemoration, forgetting, remembering to forget, fabricating memory, and so on, became significant themes in the 1990s, particularly amongst prehistorians and early medievalists, including Richard Bradley and Howard Williams (e.g. Bradley Reference Bradley2002; Gosden Reference Gosden1994; Ingold Reference Ingold1993; Thomas Reference Thomas1996; Van Dyke & Alcock Reference Van Dyke and Alcock2003; H. Williams Reference Williams2003). The relationship between temporality and the phenomenology of landscape is, perhaps, more apparent in the research of those working in prehistory, although a focus on monuments and the elite is shared by many of those examining temporality in the past (e.g. Davis Reference Davis and Yoffee2007; Meskell Reference Meskell, Van Dyke and Alcock2003).

Among all period specializations, the future has never featured prominently (though cf. Sassaman Reference Sassaman2012 and Haskell & Stawski Reference Haskell and Stawski2017). While ‘the future’ is rarely explicitly discussed in Roman-period archaeology, it is not hard to find: town-planning, deposition of hoards, votive offerings and funerary monuments all contain obvious relationships to future action, while any building, boundary, road, or well was clearly constructed with the intention that it serve a purpose into the future. Indeed, the discussion of the past in the past has always taken into account anticipation of the future, if not explicitly. Treatments of commemoration and monumentalization that include a consideration of the construction of future memory are more common amongst prehistorians, although any structure or activity that recalls the past in an enduring form is designed to function in the present and into the future. Such intentions of creation have implications for our interpretations of the roles of social memory, practice and the transmission of ideas in the inhabitation of landscapes.

The classic account of the entwining of landscape and time remains Ingold's (Reference Ingold1993) ‘The temporality of the landscape’, which emphasized the continual temporal movement of the present ‘task-scape’ in which people dwell. Looking more to the past, Gosden and Lock's influential article ‘Prehistoric histories’ (Reference Gosden and Lock1998) formulated hypotheses about the difference between the oral transmission of genealogical history and mythical history in prehistoric societies and noted that the step from acknowledging that history mattered to determining how it mattered is substantial. The process by which the narrative of the recent or distant past was understood, invented, preserved and transmitted into the future was presented by Gosden and Lock as central to ‘how’ history mattered in the past. This discussion of the method by which memories and stories about the past were communicated itself tacitly implies that the narrator had chosen a way to ensure future memory in a society without a written record. The features in the landscape maintained and negotiated over time, which they discuss as manifestations of social relationships, were artefacts serving to create memories or, in other words, to ensure future remembering. While the oral transmissions that Gosden and Lock discuss are likely to remain hypothetical, the monuments and associations in landscape that reference the past and construct a physical reminder of it were features built with the intention of their duration into the future. Barrett (Reference Barrett, Ashmore and Knapp1999), alternatively, assumed a break with the knowledge and ideas of the distant past in the Iron Age of southern Britain, but he nonetheless discussed the significance of Bronze Age monuments and mythical origins to the creation of legitimacy, authority and inheritance for future generations.

The notion that prehistoric people planned monuments to follow both long-term trajectories of development that resulted in the ‘completed’ project, as well as trajectories over shorter periods intended to transform or to culminate in destruction, provides another basis for considering the role of the future, especially in ritual landscapes (Bradley Reference Bradley2002). Through repeated practice and oral transmission, such intention could be communicated to successive generations, although it was likely to undergo substantial change over time. Significantly, such analysis of the relationship between past, present and future in the biography of a monument demonstrates that places and landscapes can be used as evidence to study the experience and meaning of the future in ways that are not linked to astronomical/cosmological orientations or calendrical systems (cf. Ingold Reference Ingold1993). Without a record of past people's thoughts, understanding their values, perceptions, cognitions and intentions will always rely (at least partly) on informed hypotheses, but analyses of this kind demonstrate the value of the pursuit.

The curation and transmission of memories of past experience are integrally connected to repetitive actions and constructing present futures. Oral histories, genealogies, narratives, explanations and other knowledge transferred from one generation to the next, or even those re-invented without connection to past people, comprise only one aspect of the social connection between past, present and future, however. Other significant examples of these temporal and social relationships include decisions to maintain or build resilience and reduce vulnerability (i.e. during periods of economic, social, political, or environmental instability, volatility, and change); to plan for sustainability; to make interventions against unknown and/or unpleasant futures; to take advantage of new opportunities; to realign social networks; and so on. These and other examples constitute some of the motivations through which past people's agency in constructing the future can be explored. A complementary view of the integral relationship and interrelatedness between past, present and future is proposed in Koselleck's ([1979] Reference Koselleck and Tribe1985) theoretical work (which, as Sassaman Reference Sassaman2012 has argued, need not be restricted to the understanding of modernity). Koselleck suggested that the conceptual categories of ‘experience’ and ‘expectation’ encompass and are more broad than ‘memory’ or ‘the past’ and ‘hope’ or ‘the future’, respectively. Koselleck argued that these concepts are fundamental to a person's understanding and construction of temporal landscapes and how they conceive of past and future constituted in the present ([1979] Reference Koselleck and Tribe1985, 256–8). Applying such a theory to the archaeology of landscape would enable a more complex interpretation of the present as constructed through any given person's experiences and expectations, which can be explored through a phenomenological study of the material remains. In turn, unpacking the relationship between past and future in a present moment can draw in other theoretical perspectives applicable at a range of archaeological scales. That is the direction this paper will take.

The intersection of tense and experience

By reflecting on the experience of being in the landscape as it relates to meaningful places as well as temporality, we can augment the typical phenomenological approach (e.g. Tilley Reference Tilley2004; cf. Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton and Whitehouse2006). Thinking thus about landscape as place and place as material culture aids our effort to capture the inherent dynamism of human agency and people's creative engagements with past and future. Dealing with ‘the future’ in the past or indeed the present is, however, a serious epistemological challenge, and we want to reflect a little more on the theoretical aspects of this here. The problem with the future, as noted already, is that it is not obviously ‘real’, but this is true of many other concepts that are nonetheless real in their consequences. Indeed, we might just as readily say that the past is not ‘real’—as, indeed, notable philosophers of time such as George Herbert Mead have done ([1932] Reference Mead2002; cf. Flaherty & Fine Reference Flaherty and Fine2001), or perhaps rather that both past and future are only real in terms of their consequences for action in a given present. In this respect, they are like a whole range of other concepts whose importance is recognized in terms of their structuring effects on action, whether or not they are tangible in themselves (Mische Reference Mische2009, 699; cf. Berger & Luckmann Reference Berger and Luckmann1966, 13–41). Even so, there is not a great deal of social theory to draw upon in trying to think about the future, as it is a neglected topic across most disciplines, except when rooted in mechanistic and teleological models of social function. Moreover, there is a legacy of ‘temporal chauvinism’ (Meskell Reference Meskell1999, 26) to deal with when we are looking at such issues in past societies, whose attitudes to the future are usually thought to be defined by cosmological concepts stressing fatalism and thus rigid conservatism (Adam Reference Adam2009). While there is some truth in this characterization for the Roman world, there is arguably a distinction to be drawn between concepts of universal time and human destiny that comprise cosmologies, and more everyday notions of futures which are implicated in all actions.

How these intersect will be an important question, but we need to develop our understanding of the latter before we can proceed any further. Tackling the question of how futures impinge upon activity in a present moment is implicit in much of the theory concerned with social action, but has only recently attracted explicit attention. Notably, Barbara Adam, one of the leading sociological theorists of temporality (e.g. Adam Reference Adam1990), led a major research project called ‘In Pursuit of the Future’ just over a decade ago (http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/socsi/futures/project.html). Some of the outcomes from this, along with a small range of other studies building upon the phenomenological and pragmatist/interactionist traditions, give us tools to work with. Adam focuses on some of the broad trends in cultural attitudes to future time, crucially without consigning pre-modern concepts to the dustbin of history and rather showing (in contrast to early archaeological work on natural/cultural times) how different time-concepts mesh in different societies (Adam Reference Adam2005; Reference Adam2009; Reference Adam2010; cf. Jenkins Reference Jenkins2002). A more detailed breakdown of different aspects of futurity is provided by Ann Mische (Reference Mische2009), who draws on phenomenologist Alfred Schutz as well as pragmatists Mead and Dewey to create a typology of ‘projectivity’. Genealogically, these represent important branches of phenomenology and pragmatism neglected by archaeologists, but which have much to offer in the analysis of everyday life (e.g. Knoblauch Reference Knoblauch, Barber and Dreher2014; cf. Gardner Reference Gardner2012). The dimensions of ‘projectivity’ which Mische identifies include: reach, breadth, clarity, contingency, expandability, volition, sociality, connectivity and genre (see Table 1). Together, these offer the potential for a nuanced understanding of the future dimension of action and its role in the constitution of situational human agency (cf. Barbalet Reference Barbalet1997; Emirbayer & Mische Reference Emirbayer and Mische1998). A further, crucial ingredient in shaping our approach to the future is to consider how this aspect of temporality, in relation also to the past, impacts upon the construction of identities, as our first example below demonstrates. Not only is identity fundamentally temporal as well as comparative in character, but past and future are often in tension in characterizing particular identity groupings in relation to continuity and change (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2002; Ybema Reference Ybema2010).

Table 1. Aspects of ‘projectivity’. (Adapted from Mische Reference Mische2009, 699–701).

Temporality and social change

The examples we will use to explore the theme of the future in the past come from Roman Britain, a context within which there have been relatively few temporalized landscape studies (e.g. Cooper Reference Cooper2016; Eckardt et al. Reference Eckardt, Brewer, Hay and Poppy2009; Gardner Reference Gardner2012; Kamash Reference Kamash, Millett, Revell and Moore2016; Wallace & Mullen Reference Wallace and Mullen2019). Central to any discussion of temporality in Iron Age and Roman-period Britain are the often over-simplified and much debated notions of cultural change and continuity, conventionally subsumed under the banner of the ‘Romanization debate’ (see e.g. Gardner Reference Gardner2013; Versluys Reference Versluys2014). Little has been said, however, of the relationship between the choice of individuals and groups to maintain traditions or make changes as a method of shaping their futures, whether or not the action resulted in the desired outcome. In earlier studies of late pre-Roman Iron Age and Roman-period Britain, traditional concepts of ‘Romanization’ espoused a view that urban and wealthy rural populations were open to change, whereas lower-status rural communities were conservative and maintained their ways of life in the face of changes happening to them (e.g. Haverfield [1906] Reference Haverfield1923; Rivet Reference Rivet1958; cf. McCarthy Reference McCarthy2013). Meanwhile, the focus of Roman-period research related to temporality is often on the monumental and high-status manifestations of the manipulation of the past in the past (e.g. damnatio memoriae: Flower Reference Flower2006; Varner Reference Varner2004), privileging urban elites. While providing excellent treatments of these contexts, these tend to recapitulate the outmoded cultural model to some degree (but cf. now Lodwick Reference Lodwick2019; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2019). This is partly because such a perspective is also a reflection of modern stereotypes, which have only become more acute and divisive in the last few years as the urban/rural split has emerged as a major political fault-line (e.g. Brownstein Reference Brownstein2016; Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Stoker and Warren2018). The application of post-colonial theory has worked against these kinds of assumptions, but by looking at the manipulation of temporality, we can explore even further a new dimension of agency and the construction of identities, through the medium of landscape.

The rhythms and cycles of agricultural endeavours have an obvious future orientation—sowing, breeding, processing and so forth are undertaken in order to create a future benefit and the maintenance of ditches and other cyclical tasks prevent future problems. They both reflect a construction of time as a cycle of experience, wherein past, present and future are intimately connected (cf. Heidegger [1927] Reference Heidegger and Stambaugh1996), but also a linear chain of actions and outcomes. Other practical actions—embellishment of or increasing the size of a dwelling, for example—may be undertaken in response to a past challenge or problem, but they also provide for a resolution in the present or future. This kind of practical planning and problem-solving was likely also related to ambitions and conceptualizations of the future that we can only conjecture, such as the increased prosperity of the next generation. Paradoxically, symbolic and ritual future-orientated actions can, perhaps, be better postulated. The construction of a funerary monument, for example, was presumably undertaken with a hope or ambition that the deceased persist into the future through the features and activities associated with it, and that the surviving family benefit from the communication of identity achieved through commemoration activities and the visibility of the monument. The social needs that were fulfilled through both practical and symbolic future-orientated shaping of landscape can augment interpretations of long-term change, experience and agency.

Two case studies are presented below to explore how social theories of temporality intersect with the understanding of the rural landscape in the Late Iron Age and Roman period in Britain. The first case study is in east Kent, where time and memory were manipulated to construct and communicate rural community identities, arguably to ensure future group cohesion in a time of rapid changes. A second case study on agency, futurity and farming in the upper Thames valley will examine evidence for agricultural rhythms and planning for the future.

Past and future landscapes in Kent

Attempting to represent or reconstruct how past people without a written record perceived time and temporal change (cf. Haskell & Stawski Reference Haskell and Stawski2017), materialized memory (cf. Mytum Reference Mytum2007) and embodied perception and cognition in the landscape with the presence and movement of their physical bodies (cf. Tilley Reference Tilley1994, following Merleau-Ponty Reference Merleau-Ponty1962) can be approached through landscape survey data. Some features, through their clarity, lend themselves to such investigation, such as monuments, structures and linear features (paths, roads, boundaries, etc.). Without the chronological specificity of excavation, survey data is of a lower resolution and interpretations must examine longer periods of time and larger-scale transformations.

As in studies centred on prehistory, it is possible to investigate the meaning of monuments and ritual to memory and temporality through Roman-period landscapes. Within the Roman-period southeast of Britain, however, the more pertinent questions of future action perhaps relate to how people used the landscape with respect to negotiating future relationships to Empire, ensuring future community cohesion, and anticipating the needs for both continuity and change. Through this case study, we intend to look at the development of a landscape, aspects of group activities, and how we can re-orientate interpretations of ‘the past in the past’ to understand what commemoration, repeated behaviours and use of older features might mean for people's attitudes to the future, to continuity and to change. This redirection of emphasis is a subtle shift in our thinking that can provide a linking step to developing an archaeology of future actions.

The Canterbury Hinterland Project has collected and synthesized a significant coverage of geophysical survey, aerial photographic and Lidar analysis, antiquarian observations and more recent surface collection, metal-detecting and excavation in the area south and east of Canterbury, which can be used to address these issues (Wallace & Mullen Reference Wallace and Mullen2019; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Mullen, Johnson and Verdonck2016). In brief, between 2011 and 2017, the project surveyed five areas using primarily gradiometry and micro-topographical survey (covering c. 120 ha), with some targeted areas of electrical resistance, ground-penetrating radar and small-scale excavation and surface collection. The results have been compiled in a GIS along with interpretations of aerial photographs, satellite imagery and Lidar anomalies covering the whole of east Kent. Digitizations of development-driven, research and antiquarian excavation plans have also been incorporated along with Portable Antiquities Scheme data and Historic Environment Record data.

The data are not complete, of course—medieval, post-medieval and modern changes include villages, curated woodlands, dual carriageways and so on that hinder both survey and phenomenological analysis. A phenomenological approach to understanding this landscape would traditionally call for the recording and analysing of a sensory experience of being in the landscape (cf. Hamilton & Whitehouse Reference Hamilton and Whitehouse2006 for a proposed methodology for conducting phenomenological research). Given the nature of the buried features and modern limitations, walking through as much of the area as possible has been complemented by GIS and visual models to approximate limited aspects of experience of place and ‘being’ in the landscape (cf. Eve Reference Eve2014 and Haskell & Stawski Reference Haskell and Stawski2017; such a method implicitly rejects the proposition, argued by Tilley Reference Tilley, David and Thomas2008, that these tools are less effective than physically walking around the landscape). The results presented here place emphasis on viewsheds and intervisibility. A person's view as he or she moved along paths, trackways, and roads can be a rich source of data for analysing the creation and experience of landscape. Focusing on future-orientated effects of creating and using paths and trackways reveals possible planning to maintain continuity and anticipate change.

In this case-study area, approximately 5 km southeast of Canterbury, the valley of the Nailbourne stream crosses the natural ridge that supported a likely pre-Roman route between Dover and Canterbury that later became the Roman-period road (Fig. 1). A likely Iron Age hilltop enclosure (Fig. 1, ‘Nailbourne Iron Age enclosure’) is situated south of and above the intersection of the ridge/road with the Nailbourne, perhaps serving as a point of control or pausing before descending from the ridge to cross the stream. A high-status Roman-period structural complex (‘villa’—rare in this area; Fig. 1, ‘Bourne Park “villa”’) was constructed in the valley, further supporting the significance of power and status in this location. A trackway connects the Nailbourne enclosure to another likely Iron Age enclosure and one of the three possible Romano-Celtic temples in the area, at Bekesbourne. The trackway continues on to a nucleated settlement at Goodnestone before turning south to rejoin the ridge route/Canterbury–Dover road. A pathway running southwest from the likely Bekesbourne temple on the trackway extends perpendicular to the road, passing by another of the possible temples at Patrixbourne, across the road/ridge, into the valley, crossing the Nailbourne between two natural springs and the Bourne Park ‘villa’, up the opposite side of the valley and (probably) onto the elevated position of three Roman-period burial mounds at Gorsley Wood (Fig. 1). The trackway and path reflected (and enabled) actions that brought people together, such as worship or sacrifice, mourning, commemorating, and congregating for rural markets or fairs, and can therefore be used to investigate the inscription and embodiment of group identities in the landscape. A brief demonstration of the application of this theoretical orientation follows below in an analysis of the experience of the landscape between the Roman-period burial mounds at Gorsley Wood (excavated in 1882/3: Vine Reference Vine1883) and the likely Romano-Celtic temple at Bekesbourne (identified through CHP aerial photographic analysis), which were connected by a path (identified in the CHP magnetometry survey of Bourne Park and also through CHP aerial photographic analysis: see Wallace & Mullen Reference Wallace and Mullen2019; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Mullen, Johnson and Verdonck2016).

Figure 1. Case study area in east Kent showing a selection of Iron Age and Roman-period evidence. (NB: polygons representing features are exaggerated with thickened outlines here to make them more visible at this scale.) (Inset upper right) location of area within east Kent. (Inset lower left) comparison of the surface elevation profiles of the path (top) and a hypothetical alternative path along the valley (bottom) (horizontal scale as shown, height exaggerated ×5 for clarity). A: Gorsley Wood Roman-period burial mounds; B: Nailbourne stream between natural springs and ‘villa’ buildings; C: Canterbury–Dover road; D: Bekesbourne Romano-Celtic temple and trackway. (Lacey Wallace and Chris Blair-Myers with Kent Historic Environment record data and background DEM data, Crown copyright/database right 2017, an Ordnance Survey/EDINA supplied service.)

Visibility analysis of what a viewer standing at the Gorsley Wood burial mounds could see reveals that the view from the mounds excluded the more quotidian sphere of the likely domestic structures within the valley (i.e. the ‘villa’), giving greater emphasis through visibility to the location of the former Iron Age hilltop enclosure, the ridge/road, the three possible temples and the nucleated settlement at Goodnestone (Fig. 2, lower left). People at the mounds could process time within the landscape with their own embodiment of it in a way that was not possible in areas of more reduced visibility, such as in the valley. Monuments of commemoration construct future memory and create a place for future ritual and memory reproduction, of course, but the meaning created by the visibility from this location also ensured the future social connections between the visible features and the group activities they hosted. By ascending to the site of the burial mounds and expanding the visible area, people increased the scope and quantity of available information, as well as their abilities to make visual and temporal connections across space. A link, therefore, may have existed between status (i.e. those who commemorated their dead in such monuments) and temporal significance of the landscape through the greater knowledge of the visual links in creating their perceptions of landscape and constructions of time and place within it.

Figure 2. Visibility analyses of the area shown in Figure 1. Visible areas are approximate as modern features and the 5m pixels (using OS Terrain 5) limit precision. (Lacey Wallace and Chris Blair-Myers with background DEM data, Crown copyright/database right 2017, an Ordnance Survey/EDINA supplied service.)

The experience of using the path that connected the mounds to the Bekesbourne temple and the trackway provides another way to investigate how people anticipated and planned for the future, with reference to the past and in the context of group activities and ritual. Both visibility analysis, analysis of the digital elevation model, and physically walking along the part of the path within the geophysical survey area (Bourne Park) have been employed to produce the interpretations here.

This path would have measured about 4.5 km, but the descent from 100 m elevation at the Roman-period barrows down to 30 m at the ‘villa’ and springs, back up to about 80 m at the road, down to 50 m and up to 60 m at the Bekesbourne temple (Fig. 1, inset lower left) required more than the time it would take to walk the same distance along a flat surface—which would be less than an hour at an average pace. There is a flatter, but more circuitous route (Fig. 1, inset lower left), so taking this path was a choice—a decision to leave aside other duties, sacrifice time and expend greater effort. Following it, across the grain of the topography, perhaps to pause at the meaningful places along the way and look back, and to be aware of the expense of energy and time, was an aspect of what made following the path a significant activity.

The Roman-period burial mounds passed out of sight (Fig. 2, upper left) quite quickly after descending the slope into the valley. As one neared the crest of the valley on the side opposite the Gorsley Wood barrows, perhaps needing to pause after climbing just over half the slope, the path passed by two Bronze Age burial mounds (Fig. 2, upper right)—present today only as ring ditches in the geophysical results—twice the diameter of those Roman-period mounds across the valley, but perhaps much eroded in the millennium they had been standing.Footnote 1 It is also at this point along the path that the Gorsley Wood mounds came back into view, having been hidden by the brow of the hill until then. While the identities of the individuals potentially buried within them and the social structure that they represented undoubtedly passed beyond actual memory into the realm of myth and legend, the obscurity of their origins may have been a boon to those who wished to imbue them with social significance that served their needs in the present and the future (cf. Dark Reference Dark and Scott1993; Meade Reference Meade, Croxford, Eckardt, Meade and Weekes2004; Semple Reference Semple2011; van Beek & der Mulder Reference van Beek and der Mulder2014).

By the design of the path to intersect downslope from these monuments, the visibility was restricted to highlight the path, valley and Roman-period burial mounds and to increase the prominence of the Bronze Age barrows. The similarity of the mode of constructing burial monuments over a probably incomprehensible period of time entwined long-term pasts—and futures—and the short-term cycles of everyday life and practice. Through the path connecting these Bronze Age barrows and the Roman-period mounds, the community made reference to the older monuments and created a link between themselves and the land through the suggestion of community continuity from the deep past into the present and preserved as future memory by way of repeated activities of procession, commemoration, worship and sacrifice formalized by the burial site, path and temple. The local population may have been reaffirming the persistence of their place within this landscape as a method of increasing cohesion amongst this rural group, perhaps increasingly drawn towards new opportunities and social networks further afield (i.e. in the urban centres, across the Channel, etc.).

The path itself reinforces this meaning: by linking the ‘new’ mounds with people moving across the landscape down to the domestic enclosure in the valley, the space for the present and for living into the future is physically and symbolically linked to the space for the dead and for remembering, both through the visible linear feature and through the actions of the people. The way that the path passes between the natural springs and the ‘villa’ structures uses this temporal association to connect the work and leisure of home, the spirits of place and gateway to the supernatural represented by watery places, and the embodied practice of remembering those who have died. Because the path leads to a Romano-Celtic temple (the next point along the path from where the Roman-period burial mounds are visible after passing the Bronze Age barrows and crossing the ridge: Fig. 2), it also connects the future-oriented religious rituals of request, worship and gratitude with the process of replicating memories. The path also led onto the trackway connecting people to the other likely Iron Age enclosures and the Goodnestone nucleated settlement, creating an enduring link to memory and group activities that would ensure community cohesion into the future. Connections like this across relatively large areas bring people together during the important moments of life, death and worship that represent the cycle of the year and of the generations, all of which are embedded in this landscape. In this way, past experiences—the memory of the deceased, the cremation and burial ritual process, etc.—were made present and past occurrences (the ‘mythological’ or constructed cultural memory of the construction, use and meaning of the Bronze Age barrows) were processed within a person's actions and embodiment of the landscape (cf. Koselleck [1979] Reference Koselleck and Tribe1985, 261).

This analysis of the path and related features provides a way to interpret how people chose, and were directed, to move through the landscape, planning for repeated and future incorporation of memory into the mind and body (cf. Connerton Reference Connerton1989). By anticipating repeated ritual activities and the future presence and movement of people, the inhabitants linked meaningful ‘places’ to action and to manipulations of the significance of the past, present and the future. Rather than becoming entrenched in conservative practices and cementing an idealized construction of the past, these people were choosing new options for constructing a landscape imbued with meaning and complex relationships to time, endurance, belief and group activities. By designing experiences focused on places of power, status and local cultural memory (i.e not reliant on or related to the road leading towards the urban centres), the rural community could strengthen their cohesion, which provided a way to ensure future relevance and their claim to the land.

In terms of Koselleck's paradigm, the visual connections, activities and movement through the landscape cannot be extricated from the manipulation of temporality because they represent constructions of the present that rely on experience and expectation. Experience and expectation are directly represented in the material/monumental and indirectly reflected in the ephemeral embodiment of the landscape that can be interpreted from the pathway and visibility analyses. Consideration of the significance of landscape experience and anticipation in these terms provides greater scope for and complexity of interpretations than an exploration of ritual or ‘the past in the past’ alone.

Making and breaking routines in the upper Thames valley

Our second case-study area to use to explore these sorts of ideas is in the west of Roman Britain, in the region to the south of the Roman and later town of Cirencester. Like Canterbury, Cirencester became a major public town in the later first and early second centuries ad, and it too sits amidst a complex landscape, albeit with a considerable number of villas, particularly in the Cotswolds to the north. The upper Thames valley, to the south of the town, is perhaps better understood from modern excavation, though, as this region has seen much more developer-funded archaeology in recent years. Oxford Archaeology have published a number of sites in this region, and these give us detailed evidence for rural lifeways that we can use as a basis for thinking about how concepts of past and future were entwined in the materiality of place. Among the best known are Cotswold Community, excavated from 1999 to 2004, and Claydon Pike, dug from 1979 to 1983 (Figs. 3, 4; Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010). In terms of the typology of futurity discussed by Ann Mische, perhaps the most straightforward aspects to address with this sort of evidence are reach, breadth, contingency, expandability, and connectivity. We can also certainly talk about the concept of the ‘recurrence’ of the past into the future on a number of levels.

Figure 3. General location map of area surrounding Cirencester in the Roman period; Cotswold Community and Claydon Pike circled. (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 374, with additions; © Oxford Archaeology, used with permission.)

Figure 4. Mid-Roman site phases at Cotswold Community and Claydon Pike. (Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 120; Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 94; © Oxford Archaeology, used with permission.)

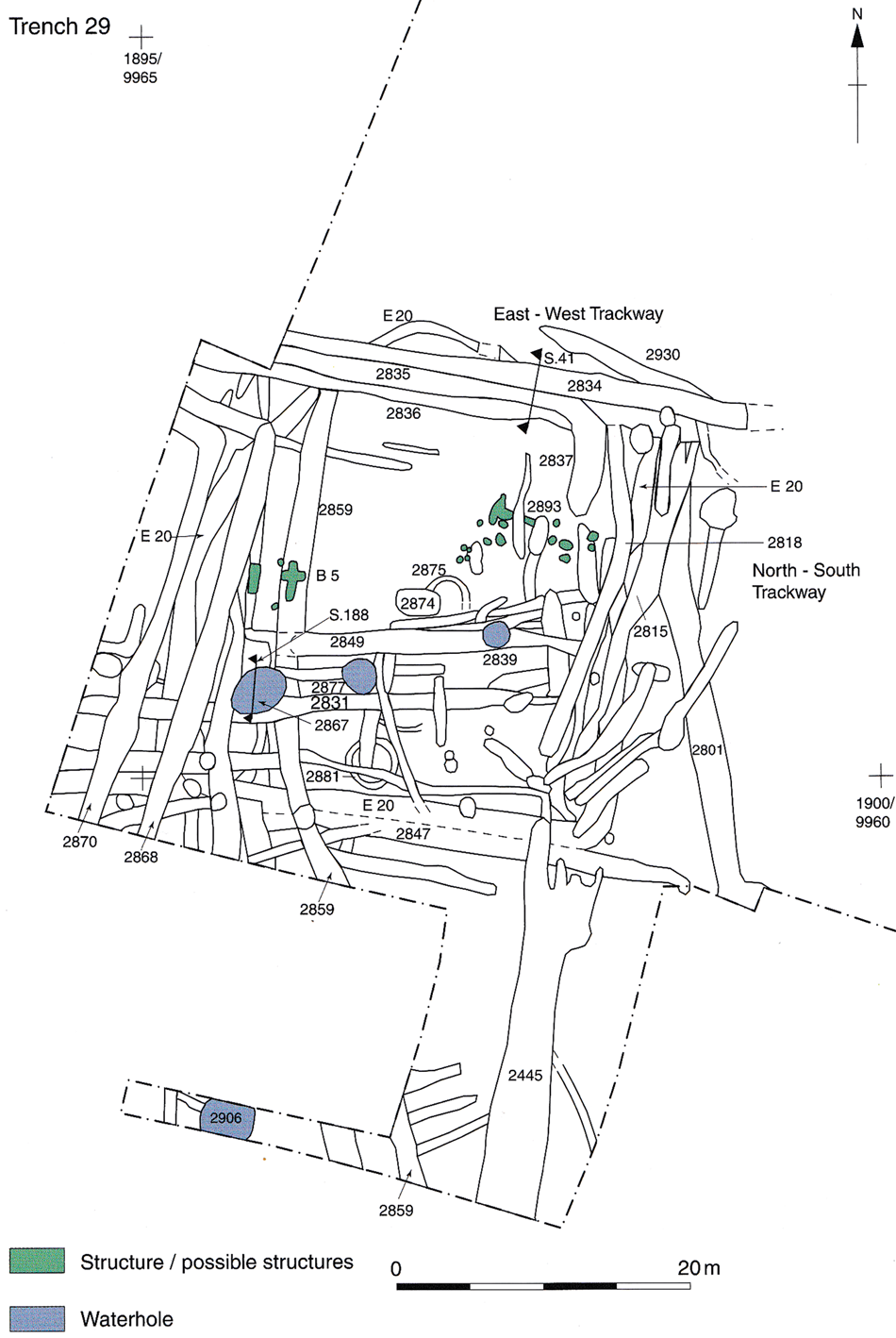

This concept is embedded in significant ways in the rhythms of agricultural life that we can capture a general flavour of across Late Iron Age and Roman Britain. Indeed, the dominance of cyclical temporal orderings of activity in the growing of crops and the rearing of livestock is perhaps one reason why rural lifeways are often regarded as less progressive than those of urban-dwellers with a seemingly more ‘linear’ temporality. While we can certainly problematize those assumptions, there is a considerable body of research on the architectural and other evidence from later prehistory, and from across Britain, which emphasizes the profound entanglement of agricultural cycles and almost all aspects of living in rural settlements. Whether considering the practical and metaphorical associations of different spaces within a roundhouse, and their orientation within enclosures, or these enclosures themselves and the trackways which connected them, there seem to be recurrent patterns. These link seasonal activities and repeated routines of movement to associations with light and dark, life and death, and growth and decay, which seem all-pervasive (Chadwick Reference Chadwick, Croxford, Eckardt, Meade and Weekes2004; Reference Chadwick2016; Giles & Parker Pearson Reference Giles, Parker Pearson and Bevan1999; McCarthy Reference McCarthy2013; Taylor Reference Taylor2013; M. Williams Reference Williams2003). The repetition of many agricultural practices manifests a series of attitudes to the future based upon reproduction of what was done in the past to secure the continuation of food production, minimizing risk and entailing perhaps another set of cyclical concepts to do with reciprocity, in terms of the social relationships connecting inter-dependent communities (Grey Reference Grey2011). In terms of longer-term scenarios, the aspect of rural life which has perhaps most preoccupied researchers is tenure and the continuity of households (e.g. Smith Reference Smith1997), which is indeed a major concern of contemporary farming families revealed in sociological studies (Gill Reference Gill2013). The evidence for routines, risk aversion and actively maintained continuity—and therefore a perhaps limited reach and breadth of futurity—is certainly readily detectible on the Romano-British farmsteads in the upper Thames valley. For example, many of the enclosure boundaries at both sites mentioned exhibit characteristic signs of repeated maintenance, recutting and minor adjustments along established lines (e.g. Trench 29, phase 3 (mid-Roman) at Claydon Pike: Fig. 5). The environmental evidence gives the clearest indications of the usual cycles of plant growth and processing, or animal breeding and management—the inhabitants of Claydon Pike seem to have focused on haymaking in the mid Roman period, while at Cotswold Community there was a mixed arable and pastoral regime, each with their own temporal sequences (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 165; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 118, 142; cf. Lodwick Reference Lodwick2017). More social cycles, perhaps relating to regular festivals as well as the bonds of reciprocity, are indicated by evidence in the faunal assemblage for feasting at Claydon Pike (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 163). All of these features might be interpreted as emphasizing a predictable and repetitive future orientation.

Figure 5. Successive ditched enclosure cuts/recuts at Claydon Pike. (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 117; © Oxford Archaeology, used with permission.)

This, however, is not the whole story, and other framings of the future are manifest in different aspects of these places as material culture. Most clearly, these are visible at points of disjuncture in the site sequences. While these might readily be ascribed to a whole host of factors, there are some consistent patterns across the sites in the region that indicate that there were certain periods when decisions had to be made that represented at least a partial break with the past, and therefore a different conception of the future. At the same time, there are forms of evidence that suggest that people sought to reinforce the predictability of the future in what we would call the religious domain, and perhaps that this was more pronounced at times of uncertainty. In relation to the first of these themes, while the Roman annexation of this part of Britain in the 40s ad is not detectable on the average rural site, there are more widespread episodes of change in the early–mid second century, the end of the third/beginning of the fourth century, and around the end of the fourth century (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 373–403). These periods are generations apart, but what happens in each of them is a significant change to the materialization of places and suggests that different futures could certainly be envisaged and acted upon than those manifest in the normal flow of life. These are evident in major changes to settlement organization and architecture at both Cotswold Community and Claydon Pike (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 159–65, 206–9; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 119, 164). It is hard to avoid the conclusion that these periods of change were fundamentally linked to developments in Cirencester, and that therefore the introduction of an urban-rural dynamic into Britain was more important than anything singularly ‘Roman’. While the different communities were thoroughly interconnected, their distinct rhythms and temporalities were equally significant, and perhaps created boundaries of identity (indeed, there is some evidence this was manifest in personal adornment: Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 345). The demands of the town population for foodstuffs—for both humans and animals—and migration of people to join this population as it developed in the early second century created opportunities—new futures—and perhaps tensions for the rural population to the south (Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 142–3). This duality is evident later on, too, when sites like those highlighted here were drawn into the coin-based economy in the fourth century—itself indicative of a change in futures embedded in different systems of exchange—only to be exposed to greater risk when the coin supply stopped at the beginning of the fifth century (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 397). What future people envisaged then—when economic structures but perhaps not cultural ones were radically transforming around them—is vital to understanding the end of Roman Britain.

The scale of economic disruption at the end of the fourth century and beginning of the fifth is a hotly contested topic and the evidence from our sites is mixed. Certainly, Cotswold Community seems to have been abandoned at this time, but the excavators suggest that the inhabitants may simply have moved to Cirencester, which is one of the Roman towns with a case for continuity into the fifth century (Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 166). In earlier periods of uncertainty, other mechanisms for controlling the future may have off-set the risks associated with changing the agricultural focus or the settlement organization of these communities. At Cotswold Community, mid-Roman burials were placed into long-standing boundary features, while in the late Roman phase burials were associated with a still visible Bronze Age barrow (Powell et al. Reference Powell, Smith and Laws2010, 136–8, 165). At Claydon Pike, ‘ritual’ features include a possible sheep-burial foundation deposit in the new early second-century aisled building and an enclosure which may have been a small shrine. The later Roman revamping of the same site to a more conventional villa was accompanied, a generation later, by the building of a more definitive circular shrine, while inhumations also took place in established boundaries (Miles et al. Reference Miles, Palmer, Smith and Perpetua Jones2007, 163–4, 208–9). Just as we saw in the Kent case study, seeking to control the past is really about the future, and all of these features can be seen in the same light, taking us into the notions of volition and connectivity in Mische's scheme. Returning also to Barbara Adam's discussion of cultures with an emphasis on fate, this can be detected in a good deal of Roman religious practice, which had whole priesthoods devoted to finding out what the future held for people (Adam Reference Adam2005; cf. Graham Reference Graham2006, 125–48). Equally, though, widespread evidence of the kinds of practices mentioned here shows how people sought to influence the future, whether or not they believed that influence was mediated by other entities. In this, and every other aspect of the archaeology of these rural settlements, we can see just how much of the materialization of landscape is imbued with ideas about temporality, in particular the relationships between past and future.

Conclusion: the new temporalities of landscape

The two case studies presented in this paper highlight distinct but interlocking aspects of the materialization of time in particular places. In viewing place as material culture, we are seeking to join up some of the disparate approaches to past experience of landscape with biographical perspectives on sites and artefacts and studies of the involvement of objects in the shaping of identities. The architecture—broadly defined—of settlements, and their situation in relationship to other features in a landscape, are important parts of the temporal orientation of the people who constructed and lived in these places. Together with movement along the pathways which connected them, these were all practices which both took time and made time. We see the understanding of more everyday routines, and their transformation, as contributing to a broader phenomenological project than that which flourished in the 1990s and early 2000s (cf. Brück Reference Brück2005). Partly, this comes from integrating typical domestic sites, of the sort in which the majority of people in Roman Britain lived, with more monumental features like barrows. It also involves the enfolding of neglected strands of phenomenological theory into archaeological practice, where the work of Alfred Schutz, for example—who reversed Husserl's bracketing out of everyday life to construct his phenomenological sociology—might hold considerable potential to resolve some of the acknowledged problems with the approach (Barber Reference Barber and Zalta2018; Brück Reference Brück2005; D. Johnson Reference Johnson2008, 137–63; M. Johnson Reference Johnson2012; Moran Reference Moran, Gardner, Lake and Sommer2016). Conceptions of the future can certainly be made more central to our interpretations in this way.

Furthermore, such considerations can yield fresh insights into the political dimensions of complex social changes like those occurring in Roman Britain. Especially in a context like this, the political dynamics of imperialism and the introduction of an urban/rural relationship require us to interrogate the evidence carefully, as both of these relationships involve contested time-concepts (cf. Cornell Reference Cornell, Cipolla and Hayes2015; Nanni Reference Nanni2011). While some aspects of Roman-period temporal experience are understood quite exhaustively from written evidence (which may not in any case be applicable to large swathes of the rural population in Britain) in terms of their basic calendrical components, and some of their religious significance (e.g. Feeney Reference Feeney2007; Salzman Reference Salzman1990), their wider cultural and political implications are only beginning to be explored (e.g. Gardner Reference Gardner2012; Hannah Reference Hannah2015). This brings us back to the centrality of temporality to our understanding of situated past human agency. We have emphasized the necessity of thinking about the future dimension of this process because it is particularly important in understanding how people act ‘in their time’, and because stereotypes about conservatism and creativity are easy to fall into. Such stereotypes are all-pervasive in our own time, and increasingly relevant as we debate an unexpectedly lively twenty-first century. Once we start to consider how the diaphanous notion of ‘the future’ shapes everything we do, it is hard to escape the conclusion that it is the most important tense. While seeing the past from the present is unavoidable, we need to identify our own temporal preconceptions and try to re-imagine the future from the perspective of a person walking across the Bourne Park landscape, or recutting a ditch at Cotswold Community. By redirecting our perceptions of past time concepts and producing such future-orientated interpretations, we can augment our approaches to agency and intentionality, advance our understanding of past landscape experience, and contribute to more complex and nuanced narratives of social continuity and change.

Acknowledgements

This article has developed out of two papers. The first was aired at the ‘Shapes of Time: Recurrence in Material Culture’ colloquium (University of East Anglia, October 2017) and we warmly thank the organizers Anastasia Moskvina and Sarah Cassell for including us. The second version was delivered in the ‘Futures of the Past’ session that the authors co-organized with Ben Jervis at the Theoretical Archaeology Group conference (Cardiff, December 2017). We thank the participants and discussants in both sessions for their thought-provoking questions and comments. We would also like to thank the editor, and anonymous referees, for their very helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.