Archaeologists are increasingly turning to posthumanism, the new materialism and corporeal feminism (henceforth posthumanism). And for good reason. These theories transform how we see ourselves and our research, challenging humanism's presupposition that humans are ontologically distinct from and inherently superior to things, animals and plants by focusing on how people emerge through and are affected by their relationships with non-human entities. Yet, as argued below, identifying anthropocentrism as the main (if not the sole) issue with humanism has led most posthumanists to ignore another important aspect of humanism; its overrepresentation of one group of Homo sapiens—white, economically privileged, cis-gendered, heterosexual men—as the model for humanity writ large. Those who cannot measure up to this racialized conception of the human are rendered not fully human. Furthermore, the act of excluding people from this narrow definition of the human allows this ontological category to come into being, with those deemed not fully human serving as a reference point against which the human is defined. In other words, since humanity is equated with white, straight, economically privileged men, this ontological category only exists in relation to poor, queer women of colour. In this article, I argue that posthumanist archaeologies’ attempts to undo anthropocentrism often rely on humanist conceptions of who counts as fully human and humanism's misrecognition that its conception of the human cannot exist without defining most Homo sapiens as not fully human. This is not to say that archaeologists should not critique and attempt to move beyond the artificial divide between humans and non-human things/plants/animals. Rather, our attempts to dismantle humanism are incomplete if we do not combine our efforts with Black studies’ long history of addressing the equally artificial divides among Homo sapiens that created and sustains humanism.

Scholars associated with the Black radical tradition have argued for centuries that humanism is an intellectual project devoted to colonialism, slavery and racial capitalism and was created to provide an ontological justification for these forms of oppression (e.g. Daut Reference Daut2017; Douglass [Reference Douglass and Foner1854] 1950). And these discussions have become increasingly common in twenty-first-century Black studies (e.g. Jackson Reference Jackson2020; King Reference King2019; Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014; Wynter Reference Wynter2003; Reference Wynter, Gordon and Gordon2006; Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015). But the leading figures of posthumanism have not incorporated this literature into their theories, and in the rare instances where posthumanist archaeologists cite these scholars (e.g. Arjona Reference Arjona2017; Schwalbe Reference Schwalbe2020), their critiques of humanism are not discussed. Several scholars (e.g. Davis et al. Reference Davis, Moulton, Van Sant and Williams2019; Ellis Reference Ellis2018; Erasmus Reference Erasmus2020; Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Reference Jackson2015; Reference Jackson2020; King Reference King2017; López Reference López2018) have noted posthumanists’ failure to engage with Black studies’ critiques of humanism and how this leads them to continue using humanist conceptions of who is included in the ontological category of the human. This article applies Black studies’ critiques of humanism and posthumanism to posthumanist archaeologies, showing that archaeologists repeatedly slip into humanist conceptions of the human even as they attempt to move beyond this ideology. Pointing out these humanist missteps and the ways they reiterate humanist understandings of the human is important. The works of Giles Deleuze, Bruno Latour and others have shaped archaeological praxis in profound ways. But these interventions can only reach their full potential if archaeologists—including white archaeologists like myself—also engage with Black studies’ critiques of (post)humanism.

The first half of this article reviews the counter-humanist and posthumanist critiques of humanism, paying particular attention to humanist conceptions of the human that go unaddressed in the latter. The second half applies this discussion to symmetrical and posthuman feminist archaeologies. To ensure my terminology is consistent throughout the article, I follow Zimitri Erasmus (Reference Erasmus2020) in using posthumanism as a catchall term for non-anthropocentric theories popularized by the new materialism, animal studies and corporeal feminism (contra Crellin Reference Crellin2020a) and ‘counter-humanism’ when referring to Black studies’ critiques of humanism. I also take Christen Ellis's (Reference Ellis2018) lead in using ‘human’ to reference the culturally constructed ontological category of the human and ‘Homo sapiens’ when talking about people in general regardless of the ontological categories they have been placed into. Finally, I lump non-human things, plants, animals, etc., into a single category instead of attending to the incredibly important differences within and between these types of entities and the various ways they act on and are shaped by Homo sapiens. Unpacking these is beyond the scope of this article, but I direct readers interested in how racialized conceptions of humanness emerge in and through animals to the work of Mel Chen (Reference Chen2012) and Zakiyyah Jackson (Reference Jackson2013; Reference Jackson2016; Reference Jackson2020).

Following the traces of humanism

Humanism is a wide-ranging ideology that has fundamentally rewritten how many Homo sapiens understand what it means to be human. The traces (sensu Trouillot Reference Trouillot1995) of humanism's emergence lay scattered across the globe (Lowe Reference Lowe2015), and scholars have followed them down two divergent paths. One leads from fifteenth-century Europe to Africa and the Americas. Black studies scholars use traces found on this path to demonstrate how humanist definitions of the human emerged through and were used to justify colonialization and racial slavery. The other path also starts in Europe, but largely stays on the continent to explore the emerging ontological divide between Homo sapiens and non-human things/plants/animals. When these paths venture into Europe's colonial projects, scholars are more likely to discuss how this human/non-human split emerged from attempts to dominate colonial landscapes (e.g. Haraway et al. Reference Haraway, Ishikawa, Gilbert, Olwig, Tsing and Bubandt2016) or the role humanism played in advancing colonialism after it was formed (e.g. Latour Reference Latour1993) than how humanism emerged from the oppression of colonized and enslaved people. Neither pathway is complete on its own, and we cannot fully reckon with the very real damage done by humanism without combining them (Ellis Reference Ellis2018).

The Black studies critique

Theorists associated with the Black radical tradition have critiqued humanism since the early nineteenth century (e.g. Césaire Reference Césaire1972; Daut Reference Daut2017; Douglass [Reference Douglass and Foner1854] 1950; Fanon Reference Fanon and Markmann1967; also see Erasmus Reference Erasmus2020, 56–7). But the most poignant and influential criticism has come from Jamaican literary theorist Sylvia Wynter. Since the 1980s, Wynter has sought to undo humanism's conception of the human as a stable, biologically defined entity, proposing instead that the human should be seen as a contingent, biocultural hybrid, emerging from both our biologies and the embodied narrations Homo sapiens tell about themselves—a theorization of humanness that is aligned with many archaeological/anthropological theories (see Watkins Reference Watkins2020). Since Homo sapiens began telling stories, these have defined what it means to be human and how we relate to others (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015, 217). Such narrations do not override biology, which forms the ‘first set of instructions’ that shape how we act (Wynter & McKittrick Reference Wynter, McKittrick and McKittrick2015, 26–7). Storytelling merely creates a ‘second set of instructions’ that generate ontological categories through which Homo sapiens understand themselves and the worlds they inhabit. In other words, Homo sapiens are biological creatures living in material worlds, but we create and inhabit the ontological category of the human through the stories we tell (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015). This makes being human something that must be performatively enacted (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015, 195–6; Wynter & McKittrick Reference Wynter, McKittrick and McKittrick2015, 23).

These narrations, Wynter argues, are often used to exclude select groups from the ontological category of the human by dividing Homo sapiens into a ‘We/Us’ who count as symbolically alive full humans and a ‘They/not-Us’ that become symbolically dead human others (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015, 220). These others are not seen as inhuman but defined as differently (and often inferiorly) human, and Homo sapiens’ ability to see themselves as fully human exists only in reference to these abject others (Jackson Reference Jackson2020, 20). Simply put, Homo sapiens define themselves as fully human by comparing themselves to others they have defined as differently and incorrectly human. In most cases, Homo sapiens do not consider themselves to be the authors of these narratives, instead crediting them to extra-human agencies (gods, laws of nature, etc.), which naturalizes the split between full humans and human others and any inequalities that emerge from this divide (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015, 217–18, 225–7).

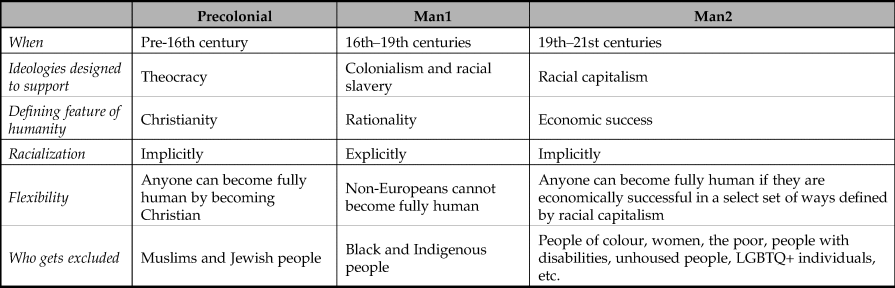

Before their fifteenth-century colonial projects, Europeans described humanity in Judeo-Christian-Islamic terms ‘based upon degrees of spiritual perfection/imperfection’, expressed as the Great Chain of Being (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 287). Those who accepted Christianity became fully human, while ‘heretics’ who rejected it became enslavable human others (Table 1). Through colonization, Europeans encountered Indigenous people who could not be subjugated under the existing definitions of the human, as they had not rejected Christianity (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 293; 2015, 227). However, new understandings of humanity emerged to justify colonial projects, which Wynter calls Man1. These secularized the Chain of Being, creating ‘differential/hierarchical degrees of rationality … between different populations’ (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 300–301; 2006, 122). Europeans occupied the most rational position, while sub-Saharan Africans were relegated to the lowest rung, burdening Africans ‘with the specter of abject animality’ by defining them as ‘animals occupying human form’ residing at ‘the living border’ of humanity (Jackson Reference Jackson2016; Reference Jackson2020, 22, 27). While this was initially developed by early colonial thinkers like Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, it was later reiterated by individuals like Thomas Jefferson (e.g. Reference Jefferson1788) and an anonymous contributor to a Virginia (USA) newspaper who wrote that Africans were ‘the connecting link between the white man and the brute species’ (American Farmer Reference American1839, 234; also see Jackson Reference Jackson2020; Wynter Reference Wynter2003). Monique Allewaert (Reference Allewaert2013) calls this way of conceiving Black humanities as a ‘parahumanity’ a racialized ontological category that enslavers understood to be simultaneously occupied by Homo sapiens yet inherently inferior to themselves and outside the category of the human. We can see these as racializing discourses, with modern conceptions of whiteness, Blackness and Indigeneity emerging from humanists’ attempts to reclassify Homo sapiens in ways that benefited colonizers and enslavers (Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014). Gender, too, played a role. Europeans used pre-colonial discourses about women's supposed irrationality to slot Black women into the most abject and animalized rung in ‘the human/animal chain’—a position so rooted in corporeal sexuality that rational self-reflection was considered impossible—thereby serving as the reference point through which the supposed ethereal rationality of European men was defined (Jackson Reference Jackson2020, 9–12; Wynter Reference Wynter, Davies and Fido1990, 356–60).

Table 1. Defining features of Man1, Man2, and European definition of the human before colonization.

These reason-based definitions of the human changed throughout the nineteenth century with the abolition of slavery, the rise of social Darwinism and the increasing reach of racial capitalism (sensu Robinson Reference Robinson2000)—a form of capitalism where class and racial hierarchies are deeply enmeshed with one another. During this time, writers like Charles Darwin, Thomas Malthus and Herbert Spencer began crafting a new definition of humanity, Man2, based less on slotting Homo sapiens into pre-defined rungs and more on judging their ability to master natural scarcity and free-market economics (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 314–15; also see Lowe Reference Lowe2015; Weber Reference Weber1976). Those who could navigate racial capitalism to provide for themselves and their families were considered fully human, while anyone who could not successfully become a patriarchal ‘jobholding Breadwinner’ was deemed less human and therefore deserving of any oppression and/or inequalities they faced (Wynter Reference Wynter1994b; Reference Wynter2003, 321). The theocentric human-as-Christian left open the possibility for anyone to become fully human by converting to Christianity (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 299). But the secularization of the human under Man1 did away with this potentially dynamic conception of the human by imposing immutable, racialized divisions upon Homo sapiens. Man2 ended these explicitly racialized divisions, extending the possibility of becoming fully human to everyone, while simultaneously proposing an even more restrictive and exclusionary definition of the human that was far easier for white men to achieve than for people of colour and/or women because the ways it defined and measured success remained highly racialized, gendered and ableist (Wynter Reference Wynter2003; Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015).

This new way of defining the human had three important effects. First, it transformed the human other into an extra-racial and more intersectional category, as white men who failed to meet the narrow definition of the human could no longer count as fully human. However, this did not mean that everyone relegated to the status of the human other was equal, as new notions of evolutionary/genetic fitness and its supposed relationship to intelligence were used to slot people of colour into even-less-fully-human positions relative to white human others (Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 322–3). Second, older, race-based conceptions of who should, and more importantly who should not, be considered fully human continued to shape nineteenth- through twenty-first-century discourses (also see DeLanda Reference DeLanda1997), allowing people of colour still to be affected by racial violence even if they managed to become patriarchal, jobholding breadwinners. In short, the ideology of Man2 was more concerned with defining some poor white men as human others so that they could be exploited than with defending economically successful people of colour. Third, extending the (often unobtainable) possibility of full humanity to all Homo sapiens transformed Man2 into ‘an ideology masquerading as a species’ which sees itself as the only definition of the human (Ellis Reference Ellis2018, 144). Wynter (Reference Wynter, Gordon and Gordon2006, 118, 126; also see Fanon Reference Fanon and Markmann1967) argues that this has had a devastating impact on many people of colour who develop a ‘self-alienati[ng]’ and ‘unbearable wrongness of being’ caused by being classified as both normally human (i.e. Homo sapiens) and abnormally human (i.e. not someone who meets the narrow definition of full humanity within Man2). Yet other ways of being human existed before Man1/Man2 and have continued into the twenty-first century. Often, these are based on African and Indigenous ontologies and/or emerge to fit the needs and desires of those exploited by colonialism, slavery and racial capitalism (e.g. Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; Deloria Reference Deloria1973; Jackson Reference Jackson2020; King Reference King2019; Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014). For instance, some Indigenous definitions of humanness are based on one's belonging to kinship networks instead of the racialized, patriarchal logic Man2 uses to define what counts as providing for one's family (Menzies Reference Menzies2013). Or, as C. Reilly Snorton (Reference Snorton2017) demonstrates, existing at the intersection of gender, sexual and racial oppression has creates ways for Black transgender and non-binary individuals to define themselves and their humanities in ways that transgress the binary logics humanism uses to define who is (not) fully human.

Humanism has been a racializing project from its inception, with its definition of the human emerging through the creation and othering of Blackness and Indigeneity. Therefore, counter-humanist scholars consider delegitimizing and dismantling humanism to be an important part of ending white supremacy. They seek to do this by exposing humanism's reliance on ‘strategic mechanisms that … repress all knowledge of the fact that’ defining Man2 as the only way of being human is nothing more than a story used to justify violence, oppression and inequality (Erasmus Reference Erasmus2020; Weheliye Reference Weheliye2014; Wynter Reference Wynter1994a,b; 2003, 326; 2015, 207). In humanism's place, counter-humanists seek to install ‘alternative … version[s] of humanness’ where all ways of being human are considered equally valid (Wynter Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015, 230–31; Wynter & McKittrick Reference Wynter, McKittrick and McKittrick2015, 11; also see Holbraad et al. Reference Holbraad, Pedersen and Viveiros de Castro2014). Zimitri Erasmus (Reference Erasmus2020) argues that this makes counter-humanism more oppositional to humanist ontologies than posthumanism, hence her framing of these theories as against, and not an attempt to move beyond, humanism.

(Critiquing) the posthumanist critique

Posthumanism aims its critique of humanism at the artificial divide between humans and non-human things that emerged during the Enlightenment. This literature is routinely discussed in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal so rather than present it in the same depth as the counter-humanism, I will just provide a brief sketch abstracted from the most widely cited discussion of the origins of humanism within posthumanism—Bruno Latour's We Have Never Been Modern (Reference Latour1993). For Latour, humanism originated in seventeenth-century Europe as scientists and philosophers sought to create a secularized, reason-based worldview. In their attempts to attribute new sources to agencies that had previously been seen as acts of God, they developed an ontological separation between Homo sapiens and non-human things/plants/animals. This made non-humans ontologically inferior to humans while simultaneously affirming that ‘human beings, and only human beings … construct society’ and affect Homo sapiens’ lives (Latour Reference Latour1993, 30–33). This worldview, however, has never accurately described the relationship between humans and non-humans. Humanism could not stop things from acting on Homo sapiens and the social worlds we create; it could only misrecognize the source of these agencies or ignore them altogether. Latour advocates for scholars to move beyond humanism by creating new, symmetrical anthropologies that explore collectives of Homo sapiens, animals and things without placing humans in a position of ontological superiority or seeing them as the sole source of agency in the world. This allows us to trace out the more-than-human networks through which social life emerges.

As two divergent pathways, counter-humanism and posthumanism provide different frameworks for diagnosing and dismantling humanism. By addressing separate aspects of humanism, these bodies of literature complement each other and provide a critical lens for assessing where humanist thinking continues to drive counter-humanist thought, and vice versa (Ellis Reference Ellis2018, 138). In the past decade, some counter-humanists have begun incorporating posthumanism into their work to create a more holistic critique of humanism (e.g. Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; Chen Reference Chen2012; Ellis Reference Ellis2018; Jackson Reference Jackson2020; King Reference King2019; Leong Reference Leong2016; Towns Reference Towns2018). In doing so, these scholars have noted two humanist missteps that are common in posthumanism. The first has to do with the location, timing and politics of humanism's emergence. Again, Latour places the origin of humanism in seventeenth-century Europe. He further notes (1993, 97) that while humanism would go on to advance colonial projects, its origin was ‘totally distinct from [colonial] conquest’. Yet traces followed by Sylvia Wynter (e.g. Reference Wynter2003; Reference Wynter, Gordon and Gordon2006; Reference Wynter, Ambroise and Broeck2015), Zakiyyah Jackson (Reference Jackson2013; Reference Jackson2016; Reference Jackson2020), Jennifer Morgan (Reference Morgan1997; Reference Morgan2004), and others (e.g. Allewaert Reference Allewaert2013; Cañizares-Esguerra Reference Cañizares-Esguerra2004; De Vos Reference De Vos2006) tell a different story, one that started over a century earlier in the Americas and which emerged in and through colonialism and racial slavery. It was Man1's secularized definition of humanity—one explicitly based on racialized conceptions of rationality—that provided the intellectual basis for the ontological separation of “’rational, self-directed, and autonomous’ humans and non-human things that posthumanist narratives begin with (Jackson Reference Jackson2020, 13; Wynter Reference Wynter2003, 299). This does not change the argument that new definitions of the human came about through the ontological division of humans and non-humans, but it does show that this cannot be fully understood unless racialization, violence, exploitation and dispossession are included in these narratives.

The second misstep has to do with who, exactly, is included in the ontological category of the human. Since posthumanism predominantly focuses outward on the human/non-human split, it often overlooks divisions among Homo sapiens (Rodseth Reference Rodseth2015, 871). Instead, the human is often taken to be a more-or-less homogenous category in its relation to non-humans, placing all Homo sapiens in a position of ontological superiority and all non-human things/plants/animals in a position of enslavement. This minimizes histories of racial oppression in ways that are demeaning to Homo sapiens whose lives were (and still are being) destroyed by colonization, slavery and racial capitalism (e.g. Cipolla Reference Cipolla and Cipolla2017; Ellis Reference Ellis2018; King Reference King2017). Furthermore, as counter-humanists show, humanism's definition of the human was created specifically so white, economically privileged, cis-gendered, heterosexual men could colonize, enslave and extract wealth without being affected by the Homo sapiens, animals, plants and things they colonized, enslaved and extracted wealth from. As a result, humanism only puts some Homo sapiens in a position of ontological superiority (Hartman Reference Hartman1997; Jackson Reference Jackson2015; Reference Jackson2020; King Reference King2017; López Reference López2018). This superiority only exists by rendering everyone and everything else as inferior. There are exceptions to this, but these are usually in cases where positioning human others or non-human things as equally agentic advances white supremacy (Hartman Reference Hartman1997). For instance, Mel Chen (Reference Chen2012) argues that news coverage of toys tainted with lead paint describes the heavy metal as agentic, capable of causing cognitive and/or behavioural issues that can prevent white and/or economically privileged children from reaching the level of success needed to become fully human. But when lead from paint or tainted water accrues in the bodies of Black and/or poor children, it is not seen as agentic, turning any cognitive and/or behavioural issues into personal failings that render them undeserving of full humanity. This points to problems with posthumanism's conception of the human. It strives to move beyond humanism's ontological distinction between humans and non-humans. But most scholars have done this by unquestioningly retaining humanism's singular definition of who counts as human. As a result, posthumanism, as currently practised, often unintentionally reproduces harmful elements of humanism.

These critiques do not apply evenly to all posthumanist theories. Posthuman feminists, for instance, discuss the ways humanism defines the human as white, economically privileged, cis-gendered, heterosexual men, rendering everyone else less human and (at times) closer to nature (e.g. Behar Reference Behar and Behar2016; Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013; Reference Braidotti2019; Reference Braidotti2022; Ferrando Reference Ferrando2019; Reference Ferrando, Thomsen and Wamberg2020; Haraway Reference Haraway1991). As Rosi Braidotti (Reference Braidotti2022, 3) argues, the ultimate goal of posthuman feminism is ‘creating the alternative vision of “the human” generated by people who were historically excluded from, or only partially included into, that category’. While this is aligned in many ways with counter-humanism, these works have some of the same historical issues as other posthumanists (see Davis et al. Reference Davis, Moulton, Van Sant and Williams2019; Jackson Reference Jackson2015; Reference Jackson2016; King Reference King2017; López Reference López2018), seeing humanism and modernity as involved in colonialism, slavery and capitalism but not something that could only have emerged in its current form in and through the racialization of Africans, Indigenous Americans and Europeans (e.g. Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013; Reference Braidotti2019; Reference Braidotti2022, 38; Ferrando Reference Ferrando2019; Haraway Reference Haraway and Stocking1988; Reference Haraway1991; Reference Haraway2015; 2016, 48; Haraway et al. Reference Haraway, Ishikawa, Gilbert, Olwig, Tsing and Bubandt2016; Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 38–40). Braidotti (Reference Braidotti2022, 38) even writes off a focus on race as ‘setting up a provisional morality—the belief in the absolute priority of certain categories … which entails taking the calculated risk of making [race] more robust and stable than [it] is in reality’, rather than approaching race as a category than emerged in and through the humanist discourses it was entangled with (see above). This leads posthuman feminists to challenge humanism's claim to inclusivity by discussing the ways most Homo sapiens are excluded from the category of the human, but without recognizing how these exclusions allow humanism's definition of the human to exist. As a result, they retain humanism's insistence that Man is a category that exists independently of the violence and oppression done in its name, thereby approaching the exclusion of women or people of colour not as the ontological foundation of humanism but acts that postdate the development of this ideology. There are no human others involved in posthuman feminist narratives of humanism's development. There are only Homo sapiens who are excluded from the category of the human after the fact.

For example, Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing discuss the centrality of plantations to the development and implementation of humanism (e.g. Haraway Reference Haraway2015; Reference Haraway2016; Haraway et al. Reference Haraway, Ishikawa, Gilbert, Olwig, Tsing and Bubandt2016; Tsing Reference Tsing2015). However, they portray humanism as an already fully formed force directing the extermination of Indigenous Americans and the enslavement of Africans (e.g. Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 38–9). This removes explicit decisions made by Europeans about which Homo sapiens could be exterminated and enslaved and which could profit from these destructive acts from Haraway's and Tsing's discussion of humanism (also see Davis et al. Reference Davis, Moulton, Van Sant and Williams2019, 3). As a result, these narratives do not provide a space for an exploration of how the violent exclusion of Black and Indigenous people from the ontological category of the human was not just an effect of but a constitutive part of the development of humanism.

Humanist missteps in posthumanist archaeologies

Archaeology can play an important role in dismantling humanism, as our datasets provide unique perspectives on different ways of being human that existed across time and space. In the past two decades, archaeologists have made important strides in undoing the ontological split between humans and non-humans. But in doing so, they have made the same humanist missteps as posthumanists in other disciplines. I demonstrate this below by covering some of the common missteps in two approaches to posthumanist archaeology—symmetrical archaeology and posthuman feminism. This leaves out much of the archaeological literature on posthumanism. But limiting my discussion to two approaches allows for a more in-depth analysis than a broader survey could accomplish. I selected these approaches because posthumanist archaeologies exist on a spectrum (Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021, 469–71; Fernández-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Gardner, de Liaño and Harris2021), with symmetrical archaeology (one of the oldest and least attentive to Homo sapiens) and posthuman feminism (one of the newest and most attentive to Homo sapiens) sitting at opposite ends. Focusing on these, therefore, provides a holistic view of humanist missteps commonly found in posthumanist archaeologies.

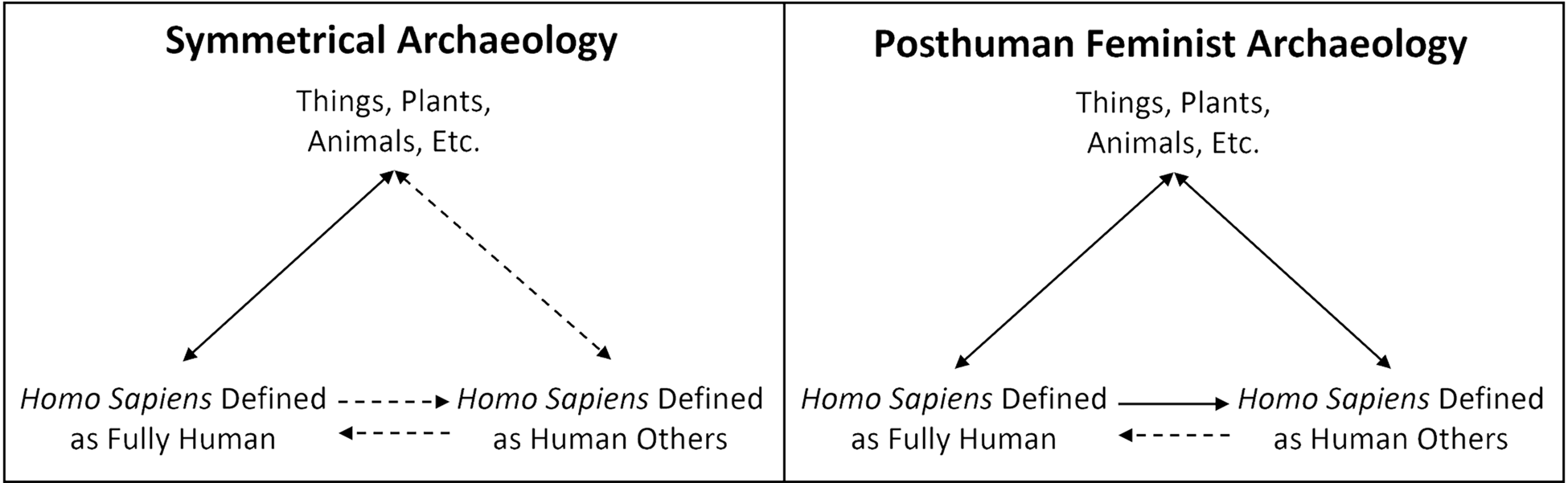

Archaeologists have a long history of critiquing posthumanism. These works generally take one of three positions. The first is explicitly anti-posthumanism, often arguing that archaeologists should abandon this theoretical framework (e.g. Barrett Reference Barrett2014; Fernández-Götz et al. Reference Fernández-Götz, Maschek and Roymans2020; McGuire Reference McGuire2021). The second sees value in posthumanism, but seeks to rein in its non-anthropocentrism (e.g. Çilingiroğlu & Albayrak Reference Çilingiroğlu and Albayrak2022; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2015; Reference Van Dyke2021). The third is pro-posthumanism, seeking to intervene without undercutting its radical potential (e.g., Cipolla Reference Cipolla and Cipolla2017; Fowles Reference Fowles2016; Hodder Reference Hodder2014). This article takes the latter position, intending to expand existing theoretical frameworks so they more adequately address the relationality between those Homo sapiens defined as fully human, non-human things/plants/animals, and those Homo sapiens defined as human others. Posthumanists like Bruno Latour and Ian Hodder often use figures and diagrams to convey their arguments. In keeping with this, I have graphically represented how I intend my intervention to reconfigure the terrain covered by symmetrical and posthuman feminist archaeologies in Figure 1. While the following paragraphs focus on individual works, my critiques are intended to be a discussion of the intellectual traditions used by these authors. Aside from my specific critiques, I consider the works cited below to be valuable contributions to archaeological theory.

Figure 1. Relationship between (1) things, plants, animals, etc., (2) Homo sapiens defined as fully human, and (3) Homo sapiens defined as human others in symmetrical archaeology and posthuman feminist archaeology, and what new relationships are needed to move these towards a counter-humanist approach. Existing relationships are depicted with solid arrows and new relationships are depicted with dashed arrows. For symmetrical archaeology, this would entail a consideration of the relationality between Homo sapiens defined as human others, Homo sapiens defined as fully human, and non-human things/plants/animals. For posthuman feminist archaeology, this would entail expanding the relationality between those defined as fully human and those defined as human others, allowing these works to analyse how the human emerges in and through the act of excluding most Homo sapiens from this ontological category.

Symmetrical archaeology

Some of the first and most sustained uses of posthumanist theories in archaeology came from symmetrical archaeology. These works draw heavily from Bruno Latour and Graham Harman's object-oriented ontology (e.g. Harman Reference Harman2010), proposing a symmetrical approach that ‘acknowledge[s] the varied qualities always possessed by things, and thus the radical differences they make to the world—both among themselves and to humans’ (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012, 12). As a result, symmetrical archaeologists often argue that archaeologists should remove humans from a position of ontological superiority within our studies by reconceptualizing archaeology as “the discipline of things” (e.g., Olsen Reference Olsen2010; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012, 1). This makes symmetrical archaeology generally disinterested in (and often dismissive of) the human half of the human/thing symmetry (contra Olsen & Witmore Reference Olsen and Witmore2015, 191; Witmore Reference Witmore2014, 215, 218). As a result, they often gloss over who defines, and who gets included in, the ontological category of the human, leading them to stumble into humanist definitions.

Bjørnar Olsen (Reference Olsen2010, 16), for instance, discusses ‘the long dictatorship of human beings’ over things, where things have been made to ‘play… the villain's role as humanism's “other”’ by defining agency as something solely possessed by ‘rational and intentional’ human ‘subject[s]’. Timothy Webmoor (Reference Webmoor2007, 568–71) defines humanism as a ‘perspective presupposing humans in a privileged position with respect to nature’ by rendering them ‘autonomous, independent beings’ who alone ‘possess intentionality’. Christopher Witmore (Reference Witmore2007, 547; Reference Witmore2014, 210–11) argues that ‘human actors’ have an ‘assumed privilege’ in their relations with non-human things, leading them to claim ‘the lion's share of mastery and control over agency’, allowing them to ‘remak[e] the world in’ their image. These statements are not necessarily problematic, as humanism (usually) places those deemed to be fully human in this position of ontological superiority. But Olsen, Webmoor and Witmore conflate the Homo sapiens allowed to count as fully human with humanity in general. Again, it is not all Homo sapiens who have been elevated in humanist ontologies, only the small groups of Homo sapiens defined as fully human, and humanism's conception of the human can only come into being by forcing marginalized people to play ‘the villain's role’ alongside animals, plants and things (see above).

A further example of what is at stake with this inattention to who counts as human can be found in symmetrical archaeologists’ recurring discussions of the need to reimagine ethics and politics in more-than-human ways (e.g. Olsen Reference Olsen2010; Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2012; Reference Pétursdóttir, Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014; Reference Pétursdóttir2017), including the creation of new democracies where humans and things are given equal weight (e.g. Olsen Reference Olsen2003; Witmore Reference Witmore2014; but see Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2012, 588). This, they argue, can undo humanism's transformation of things into ‘abject’ others, ‘faceless minions’, ‘servants’ and ‘subalterns’ (e.g. Fahlander Reference Fahlander2003; Olsen Reference Olsen2003, 100; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012, 33; Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2012, 578; Witmore Reference Witmore2007, 552). While there is nothing inherently problematic with this (but see Sørensen Reference Sørensen2013), symmetrical archaeologists’ frequent conflation of humanism's Man with all Homo sapiens makes this potentially troubling. Specifically, symmetrical archaeologists are often inattentive to how the human will be represented in these new democracies, making it likely that those Homo sapiens already deemed fully human within humanism would continue as the stand-in for humanity writ large, ensuring that power remains in the hands of those Homo sapiens who have long held it, even if they are now sharing this power with things. As a result, these proposals create the possibility of tear-gas canisters, riot shields and batons being granted citizenship in more-than-human democracies without reckoning with how the agencies of tear-gas canisters and batons might be used to deny citizenship to Homo sapiens deemed as human others by demarcating which can be beaten with impunity and which cannot (also see Cipolla Reference Cipolla and Cipolla2017, 226; Fowles Reference Fowles2016; Leong Reference Leong2016; Wynter Reference Wynter1994b). To be clear, symmetrical archaeologists do not advocate for this. But their reliance on humanist conceptions of humanity leaves a gap where such a situation could occur if these more-than-human democracies (as they are currently conceived) were to be implemented.

Most of the works cited in the previous paragraphs are not case studies where an inattention to who is (and who is not) included in the category of the human is justified by the subject matter. They are theoretical pieces that map out symmetrical archaeologists’ vision of the world. As such, their conflation of Homo sapiens with Man is indicative of a humanist misstep in symmetrical archaeology (also see López Reference López2018, 373). This can be remedied by extending the terrain encompassed by symmetrical archaeology to include the concerns of counter-humanists (Fig. 1). At a minimum, this would require adjusting the quotes above to note that only some Homo sapiens were given mastery over things/plants/animals while others were (and often still are) considered closer to these non-human entities than to being fully human. A more extensive coupling of counter-humanism and symmetrical archaeology might address the active role things/plants/animals play in dividing Homo sapiens into full humans and human others, the unexpected ways things’ physical affordances remake or even undermine these ontological categories, and how things/plants/animals are affected by these processes.

While the above deals with symmetrical archaeology's Latourian influences, Þóra Pétursdóttir's work on ruins shows that symmetrical archaeologists make humanist missteps when using object-oriented ontologies (OOO) (similar examples can be found in Witmore Reference Witmore2021). Pétursdóttir's (Reference Pétursdóttir2012; Reference Pétursdóttir2013, 48; Reference Pétursdóttir, Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014, 336–7) research includes a study of an abandoned Icelandic herring-processing station, undertaken to explore the ‘inherent otherness’ of things that emerge when humans stop treating them as ‘tamed domesticated possessions’ and allow them to become ‘unruly’ and ‘out-of-hand’. She generally does this by focusing on the ‘sincere affection, awe and wonder provoked on the very encounter with these sometimes strange things’. I focus on Pétursdóttir because her work is an excellent example of a symmetrical case study discussed across multiple publications, reducing the likelihood that my comments only apply to the framing of an individual article. The humanist missteps in this body of work I focus on relates to Pétursdóttir's discussion of the otherness of things and how they come to affect Homo sapiens. Pétursdóttir (Reference Pétursdóttir2012, 538) recognizes an inherent otherness in the things she sees at the processing station. They are strange and unfamiliar, creating ‘mixed feeling[s] of wonder, excitement and despair … what is this, what do I do with it—and how can I possibly account for it?’ (also see Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2012, 590–91; Reference Pétursdóttir2013, 45; Reference Pétursdóttir, Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014, 345).

I cannot help but read Pétursdóttir through Alfred López's (Reference López2018) critique of a classic passage in Jane Bennett's Vibrant Matter (Reference Bennett2010, 4) where she discusses feelings of revulsion, dismay and wonder caused by a seemingly random collection of debris—a discarded ‘glove, one dense mat of pollen’, a ‘dead rat’, a ‘bottle cap’, and a stick—found in a street drain in an affluent Baltimore, Maryland (USA) neighbourhood. This, she argues, shows the vibratory ‘thing-power’ of non-human entities and their ability to affect the world around them. López (Reference López2018, 377) notes that Bennett's narration is disconnected

from larger systems of wealth/poverty, safety/danger, whiteness/blackness—in short, systems of power—that would open it up to alternate gazes, alternate humanities. How might, for example, a Pakistani deliveryman, or an African American woman … feel (for this is also a matter of affect) about seeing the same items in the street …?

This disconnection ‘naturalize[s] a very particular (white, academic, middle- or upper-middleclass) gaze’, presenting ‘it as generic—and thus universal’ because Bennett's positionality is not included as part of the assemblages through which the dead rat and the discarded glove/bottle cap come to affect her (López Reference López2018, 377; also see Barad Reference Barad2007; DeLanda Reference DeLanda2016). In response, López (Reference López2018, 377) argues for more ‘expansive, inclusive narrative[s]’ that are ‘attuned to the larger systems of power in which both humans and material objects circulate’ and allow room for alternative voices that ‘could resist … contest’ or corroborate Bennett's experiences.

This same dynamic plays out in Pétursdóttir's discussion of the herring-processing station. She primarily discusses her experiences and in the few passages where she includes other people's perceptions (Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2013, 31–2, 45), they come from individuals who are (like her) outsiders to this remote landscape and are likely to have a similar socio-economic status. Pétursdóttir notes that people live in ‘nearby farmhouses’, but she does not mention their perspectives on the ruins (also see Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2021, 488). Are they, too, in awe of the processing station? Do they find a strange otherness in this place that is a part of their community? Pétursdóttir (Reference Pétursdóttir2012, 590–91) mentions being led through the ruins on at least one trip by a former worker at the station, but she notes that she was unable to concentrate on his explanations of ‘the technology in front of us’, instead caught up ‘admiring that thing in front of me’, too ‘deeply affected by the thing facing us’ to follow what he was saying. There may be reasons for the perspectives of those who live(d) in the shadow of the processing station to be left out of Pétursdóttir's accounts. But this does not mean that the positionality of those whose voices are present in the articles should be omitted. For a scholar as seemingly considerate of the world around her as Pétursdóttir, the lack of discussion of positionality and the ways it shaped her experiences is jarring. This, I would argue, results from her use of OOO, which focuses on inherent qualities of things that exist outside their relationships with other entities (e.g. Fowler & Harris Reference Fowler and Harris2015; Harman Reference Harman2010). If, as OOO argues, things have a ‘true being’, an ‘inherent otherness’, that they can ‘reveal’, then the positionality of the Homo sapiens experiencing these things cannot change how these objects affect people (Pétursdóttir Reference Pétursdóttir2013, 43; 2014, 336). As a result, only ‘a very particular (white, academic, middle- or upper-middleclass)’ perspective (López Reference López2018, 377)—the perspective of those deemed (more) fully human—is included in Pétursdóttir's discussion of the station, since within the framework of OOO there is no need to include other voices. For instance, Pétursdóttir (Reference Pétursdóttir, Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014, 345, my emphasis) recalls that the ruins ‘stir[red] within me feelings of loss, absence and incompleteness. Considering their physical state, how could they not?’ With OOO, this statement of fact, that the ruins must have this effect, can go unquestioned.

However, if Pétursdóttir instead took up López's call to account for positionality, then the ruins’ ability to create feelings of loss, absence and incompleteness can be questioned, opening up avenues for assessing how differences among Homo sapiens produced by colonization, slavery and racial capitalism allow the same things to affect those deemed fully human and those deemed human others in different ways. This might mean incorporating the perspectives of those humanism deems more human on the basis of class (the voices currently included in Pétursdóttir's work) and those it considers less human (the voices currently missing). Incorporating these various perspectives could highlight the multiple, overlapping and quite possibly contradictory ways the ruined herring factory comes to affect Homo sapiens without undercutting symmetrical archaeology's focus on the ability of things like ruins to affect people.

Posthumanism feminism

Like the posthuman feminists discussed earlier, archaeologists using this approach argue that humanism defines the human as white, economically privileged, cis-gendered, heterosexual men while positioning everyone else as less (than) human (Cobb & Crellin Reference Cobb and Crellin2022, 269–70; Crellin Reference Crellin2020a, 160; 2020b, 121; Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris, Moore, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020, 8; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2020, 45; Reference Crellin and Harris2021, 470; Fredengren Reference Fredengren2013, 55; Reference Fredengren2015, 115). They seek to undo this by proposing that the human is not an ontologically stable entity but a relational category that emerges from assemblages of Homo sapiens, things/materials, animals and plants (Cobb & Crellin Reference Cobb and Crellin2022, 271; Crellin Reference Crellin2020a, 161; Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris, Moore, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020, 4, 8; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2020, 45; Fredengren Reference Fredengren2013, 55; Reference Fredengren2015; Reference Fredengren2021, 529; O'Dell & Harris Reference O'Dell and Harris2022). This decentres humanist conceptions of humanity, making ‘space for those who were never granted full membership’ into its definition of the human (Crellin Reference Crellin2020a, 177; Fredengren Reference Fredengren2015, 111).

Counter-humanists’ conception of humanness is also relational, with the ontological category of the human emerging only through its relationship to the marginalized people defined as human others (see above). Humanism can only maintain its hold on power by obscuring this relationality, positioning its definition of the human as independent from the exclusion of those deemed human others. Applying this perspective to posthuman feminist archaeology shows humanist missteps in the ways they approach who/what is involved in the relationships through which the human emerges. These works approach the human as a category that is fully formed by interactions between Homo sapiens and non-human things/plants/animals before marginalized people are excluded from it (Fig. 1), which is in line with humanist thinking—where those deemed fully human do not owe their ontological status to those they oppress. As with symmetrical archaeologists, this omission might be justified by the focus of individual case studies. But theoretical pieces that lay out the terrain covered by posthuman feminist archaeology fail to note the ontological importance of the exclusion of marginalized people from the category of full humanity (e.g. Cobb & Crellin Reference Cobb and Crellin2022; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021; Crellin et al. Reference Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris, Moore, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020), suggesting that the inattention to the constitutive relationality between human others and those deemed fully human indicates a retention of humanists conception of the human within posthuman feminist archaeology. Despite this, posthuman feminist archaeology can be easily expanded to include counter-humanist views on the relationality between Homo sapiens deemed fully human and those deemed human others (Fig. 1), as demonstrated below through three examples.

The first example comes from Rachel Crellin's (Reference Crellin, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020b) discussion of Bronze Age warriors and especially warrior chiefs. She argues that archaeologists have understood these men in humanist terms, granting warriors the status of full humanity by endowing them with the ‘power to control the objects under their ownership’ and ‘wield their power to subjugate others’, while simultaneously rendering other Bronze Age Homo sapiens (especially women) as ‘inactive’, ‘subjugated’ human others who lack the ability to affect the world around them (Crellin Reference Crellin, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020b, 117). Crellin (Reference Crellin, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020b, 128–9) suggests that one way out of this is to see warriors and any power they possessed as relational, emerging from more-than-human assemblages—especially the assemblages of materials and knowledge that produced Bronze Age spears. This decentres the human-qua-warrior as a stable entity who alone wielded power over the denizens of the Bronze Age by distributing the power used to define warriors as fully human. While Crellin demonstrates how warriors emerged relationally in and through non-human things, she does not incorporate other Homo sapiens into her discussion, rendering the human-qua-warrior an ontological category that exists independently of the Homo sapiens warriors subjugated. A counter-humanist perspective, however, would see this subjugation as part of the relationality through which the ontological category of the human-qua-warrior comes into being. Incorporating this into Crellin's work would create a more expansive consideration of how the Bronze Age warrior is a relational category, a way of being human that emerged in and through the metals and knowledge needed to make bronze, miners who acquired this metal, artisans who made spears, and the women whom warriors are often seen as subjugating.

The second example comes from Marianne Eriksen and Kevin Kay's (Reference Eriksen and Kay2022) discussion of the ontological relationships between things, animals and Homo sapiens in Iron and Viking Age Scandinavia. They show how things like swords, houses and some animals like horses may have been treated as ontologically equal to humans, being buried in similar ways to Scandinavians who were deemed fully human thereby transforming them into bodies whose deaths could be grieved and mourned. Alternatively, burial data and historic laws indicate that infants and enslaved people (referred to as thralls) were not given the same burial treatments, positioning them below those Homo sapiens deem fully human and things/animals like swords, houses, or horses. While insightful, Eriksen and Kay do not address how the ontological category of the human in Iron and Viking Age Scandinavia was created relationally through the treatment of infants and enslaved people. Being (fully) human in this time and place was in some ways to be equated with particular sets of non-human things/animals. But it also meant not being an infant or enslaved. Therefore, these definitions of the human required some Homo sapiens to be less grievable than those Homo sapiens defined as fully human and the select things/animals that were ontologically equivalent to them. Incorporating this into Eriksen and Kay's discussion would not undermine their arguments. Rather, it would strengthen and expand what they can say about the relationship between Homo sapiens, things and animals in the Iron and Viking Ages, and how definitions of the human operated in the past.

The final example comes from Christina Fredengren's (Reference Fredengren2018, 2) discussion of how certain Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Scandinavian men were ‘made’ to become bog bodies as the result of ‘various processes of “othering” through life – and death’. Fredengren (Reference Fredengren2018, 11) demonstrates that these bodies ‘were shaped’ throughout their lifetime ‘by hardship and stress … which may have come about through a variety of power-relations that exercised slow-violence on their bodies’, most notably through a lack of adequate food. As the bog bodies were male, this slow violence may have ‘produced a particular type of geographically situated “sacrificeable masculinity”’ that was made to be ‘kill-able’ (Fredengren Reference Fredengren2018, 11), resulting in certain men being bracketed off from the rest of society and buried in bogs upon their death instead of being cremated like most other Bronze and Iron Age Scandinavians. This bracketing, Fredengren argues (2018, 3), relied on the agencies of the bog, bringing these wetlands into the more-than-human definitions of who could be killable that local political ecologies relied on. Unlike Crellin, or Eriksen and Kay, Fredengren (Reference Fredengren2018, 3, 11, 14) mentions the possibility that sacrificing these men may have benefited others. But this is not explored in any depth, leading the bog to have more of an impact on both local political ecologies and the conception of who counts as fully human (i.e. those not deemed sacrificial) than the otherized men. Despite this, a more expansive discussion of the ontological effects these men (as human others) had on Bronze and Iron Age definitions of the human can be had, one that focuses on how these ways of being human were defined (at least in part) as someone who was not a killable man who could be buried in a bog. As with the other examples, delving further into the ways that definitions of the human relied on otherizing certain Homo sapiens can strengthen and expand Fredengren's argument without undermining the work she has already done.

Conclusion

As argued in this article, the ways posthumanist archaeologies conceive of the ontological category of the human often retain elements of humanist thinking—especially in their treatment of white, economically privileged men as a stand-in for all Homo sapiens and their reluctance to engage with the ways that humanist definitions of the human can only emerge in and through defining most Homo sapiens as human others. These humanist missteps can only be assessed and remedied if archaeologists engage with Black studies, especially counter-humanist scholars like Zakiyyah Jackson, Tiffany King and Sylvia Wynter. Reckoning with this perpetuation of humanist thought within posthumanism does not require archaeologists to abandon these non-anthropocentric theories. Rather, it can only strengthen posthumanist archaeologists’ critiques of humanism by incorporating new relationalities that sharpen their arguments.

Incorporating these perspectives might mean altering them to fit times and places that are fundamentally different from those studied by Black studies scholars. In Europe, for instance, human others seem to have existed for millennia (see above), allowing for relatively straightforward incorporations of counter-humanism. But in the Americas, it is possible that the human other only emerged in and through colonial encounters (e.g. Menzies Reference Menzies2013). Or they could have developed during the rise of political hierarchies throughout the hemisphere. Archaeologists can clarify this by mapping out the ways human others have been created in and through historically contingent relations between people, things, animals and plants. Regardless of what, exactly, archaeological engagements with Black studies’ critiques of (post)humanism look like, making these intellectual connections is critical if archaeologists wish fully to comprehend and move beyond humanism.

Acknowledgements

Funding for researching and writing this article was provided by the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia (USA) through their pre-doctoral fellowship program. I would like to thank the faculty and fellows at the Woodson and the University of Virginia's Transforming Anthropology Workshop for creating an intellectual environment that allowed me to combine archaeology and Black studies. I also want to thank Tony Chamoun and Richard Handler for commenting on earlier versions of this manuscript, and Matthew Sanger, Severin Fowles, and the anonymous reviewer for providing excellent comments that strengthened my arguments. Finally, I want to thank John Robb and Elizabeth DeMarrais for their help with revising the manuscript. Any shortcomings are my own.