Introduction: challenging linearity, seeking difference

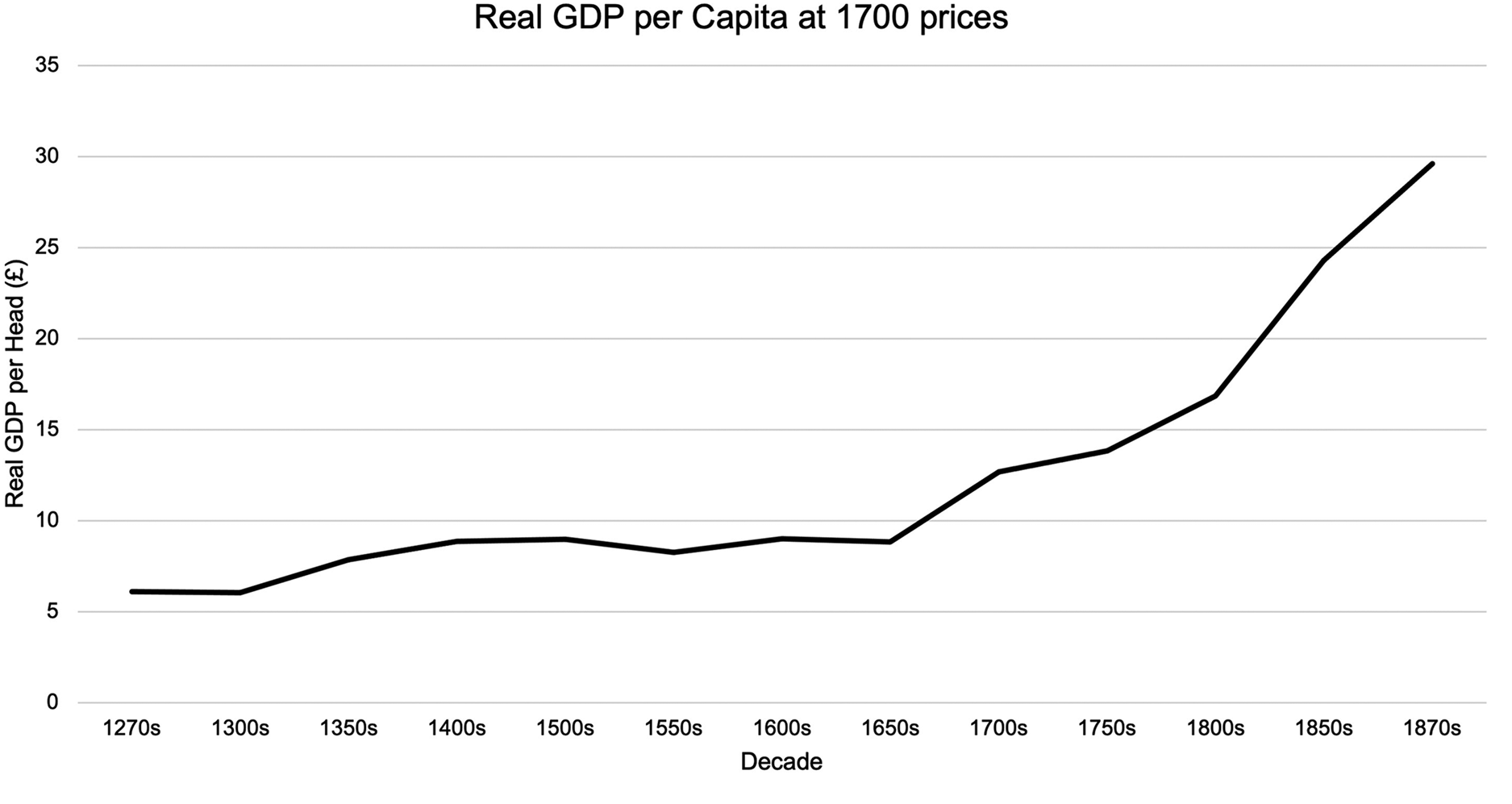

The graph in Figure 1 appears to tell a simple story of economic growth. Since the Middle Ages, the economy has grown and living standards have risen. It creates the impression that economic progress is linear, emerging from seeds sown before the Black Death and progressing onwards, accelerated by industrialization, to the twenty-first-century economy. It is certainly the case that the twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw a re-orientation of the English economy towards intensive commercial production and investment in infrastructure (e.g. Britnell Reference Britnell1996). Supported and driven by population expansion, vibrant and expansive export markets for English grain, wool and mineral resources developed (e.g. Childs Reference Childs1981; Hybel Reference Hybel2002; Kowaleski Reference Kowaleski1995, 16–18; Oldland Reference Oldland2014). Agricultural producers adopted increasingly specialized husbandry regimes and mills were erected by landowners and entrepreneurs (e.g. Britnell Reference Britnell2001; Campbell Reference Campbell2009; Dodds Reference Dodds2008; Langdon Reference Langdon2004; Langdon & Masschaele Reference Langdon and Masschaele2006). To see this as the beginnings of a process of modernization implies that the modern, capitalist, economy was pre-determined (Howell Reference Howell2010, 300), that economic development was directed towards this end point (a notion which is problematic in itself as, one hopes, we are not yet at the end!). It conceals any number of false starts and dead ends, potential economic emergences which dissolved as quickly as they developed, alternatives supressed by regulation and regimes of power. We can acknowledge that elements of our contemporary experience resonate with the ‘modern’ as it was experienced in the Middle Ages, without reducing this to an incremental process of linear development. Linearity also emphasizes the role of certain economic actors. Economic growth becomes a patriarchal narrative of progress in which the key characters are enterprising male merchants and yeoman farmers, albeit one punctuated by occasional references to ‘exceptional’ entrepreneurial women (Reyerson Reference Reyerson, Bennett and Karras2013, 298).

Figure 1. Estimated gross domestic product per capita for England 1270–1700 and Great Britain 1700–1870 (based on constant 1700 prices). (After Broadberry et al. Reference Broadberry, Campbell, Klein, Overton and van Leeuwen2016, 205.)

Posthuman interventions, particularly from a feminist perspective, critique our late-stage capitalist world's predilection for sameness, consistency and homogeneity. Braidotti (Reference Braidotti2013, 58), for example, argues that late-stage capitalism emphasizes stable categories and representation, concealing and supressing difference (see also Guattari Reference Guattari1989, 31). Irigaray and Marder (Reference Irigaray and Marder2016, 45) suggest that this serves to substitute heterogenous forms of becoming with ‘more or less arbitrarily defined forms’, supressing the potential for difference to emerge. Haraway (Reference Haraway1991, 50) characterizes a concept of linear progress as patriarchal and racist, privileging the interests and achievements of Western heterosexual males (a similar argument is made by Montón-Subías & Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2018 in relation to the role of Eurocentrism in archaeological interpretation). I am drawn to Braidotti's somewhat depressing characterization of contemporary society because it characterizes the context in which we create archaeological knowledge. Archaeological practice privileges neatness and homogeneity. We can see this in the way that archaeologists seek to draw direct links between objects or monuments and social groups (or identities), the way we classify things, privileging sameness, driven by an illusory objectivity. Archaeologists are increasingly problematizing this element of practice (see e.g. Fowler Reference Fowler2017; Herva et al. Reference Herva, Ikaheimo and Hieltan2004; Jervis Reference Jervis2019, 83–91; Van Oyen Reference Van Oyen2013) and Braidotti's (Reference Braidotti1994; Reference Braidotti2013) alternative, a non-linear and nomadic philosophy, which is concerned with difference, provides a valuable tool. For medieval archaeology, this philosophy requires us to question our ideas of the Middle Ages, to challenge the extent to which the period can be characterized as a singularity and develop new approaches to revealing multiplicity and complexity. There is a growing awareness of this challenge across medieval studies; as McClure (Reference McClure2015, 616) states; ‘in our age of multiple modernities, we must explore the history of our multiple medievalisms’. Rather than creating a clear divide between medieval and modern, or tracing incremental development between these states, an emphasis on difference and multiplicity allows us to identify resonances and threads through which experiences can be related. The purpose is to create an alternative view to the polarized position that the medieval economy is different to the modern economy, or a nascent iteration of it.

Here, I explore the emergence of difference in relation to the medieval economy. For Deleuze (Reference Deleuze1994, 186), the ‘economic’ is the virtual element of a social system (Roffe Reference Roffe, Braidotti and Bignall2019, 227–8). It exists not as a single entity but as potential within a series of relations, made actual through moments of intensive becoming: the performance of those relations. The macro-economic story of linear growth is no less real than the variegated and heterogeneous economic experiences investigated here, but is the result of particular intensities; the study of specific records, the application of certain mathematical formulae and functions at a scale intended to generalize. The purpose of my analysis is quite different, being to attend to the intimate material interactions which enfolded objects, resources and people into the emergence of what we characterize as medieval society. It is through these relations that economy emerged, not as a heterogeneous whole, but as a series of multiple threads, indeterminate and multi-directional in character (Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 23).

To achieve this, I examine the relations formed in the grinding of grain. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, milling became increasingly mechanized, with the erection of water- and windmills across England (see Holt Reference Holt1988; Langdon Reference Langdon2004). A progress narrative would see investment in milling infrastructure as afforded by the intensification of agricultural production, which changed the temporal cycles of sowing and harvesting, of animal husbandry and of the storage and processing of grain (Campbell Reference Campbell and Sweetinburgh2010, 33; Claridge & Langdon Reference Claridge and Langdon2011). Such a narrative implies that large mills are superior to domestic milling (by which I mean handmilling undertaken in or around the home, but not necessarily for household consumption), the persistence of handmills being antithetical to a ‘driving beat’ of progress (see Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 23). Despite this investment, in the fourteenth century around 20 per cent of England's grain was milled domestically (Langdon Reference Langdon1994, 31). This did not take place uniformly across the country, being particularly prevalent in Kent and East Anglia and less common in northern England due to local legal and political factors. There is strong circumstantial evidence to link domestic milling to women (extending to the early medieval period in the form of female ‘grinding slaves’: Langdon Reference Langdon1994, 40) such as occasional references in legal documents (Langdon Reference Langdon1994, 40; Reference Langdon2004, 19, 129). Langdon (Reference Langdon1994, 31–2) argues that there was a strong commercial element to domestic milling, with households offering milling services to their community, either in the absence of, or in competition with, mechanized mills. Milling is an example of a process which, at first glance, appears to follow a simple developmental trajectory, but in fact varied contextually and led to the emergence of a patchwork of diverse, but related, economic experiences.

This economy is neatly described by Heng (Reference Heng2014, 237) as a series of ‘overlapping repetitions-with change’. Commercialization, urbanization and the growth of international markets increased demand for agricultural produce, stimulating intensification of production and the mechanization of milling. Yet production remained rooted in the household, mechanized milling did not entirely replace handmilling, and its organization probably adapted to commercial opportunities. Rather than a clear rupture, we can perceive what Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, 375–8; see Jervis Reference Jervis2019, 37–40) characterize as moments of de-territorialization and re-territorialization, in which household assemblages, which we might define as open-ended, productive, gatherings of relations (after Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 22–3; Bennett Reference Bennett2010), are pulled beyond themselves into new or alternative forms of becoming. The production, processing and marketing of grain pulled households into wider sets of relations (de-territorialization), being re-constituted as intensities of sowing, harvesting, grinding and marketing. These, in turn, de-territorialized households into relations of administrative obligation and community building. Material elements like houses, fields and querns brought persistence, a slow temporality, stimulating repetitive action, filtering the potential affect of de-territorialization, or the forms of economic virtuality which could actualize (Bennett Reference Bennett2010, 58; Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013, 165; Nail Reference Nail, Braidotti and Bignall2019, 192–3). Rather than equating mechanization to improvement and progress within a teleological narrative of economic growth and development, we can instead perceive an economy that was a patchwork of happenings, an ever-changing milieu of relations, out of which distinctive experiences, and bodies, could emerge.

Medieval milling and medieval becoming

The county of Kent in southeast England provides an interesting case study for the examination of milling relations. Here, both archaeological and historical evidence suggest that handmilling was particularly persistent. The reason is that in much of medieval England domestic milling was regulated by a custom known as ‘Suit of Mill’, which obliged tenants to use the mill of their manorial lord, usually for a toll. In some instances, they were explicitly banned from using handmills and there was no possibility for tenants to establish their own milling infrastructure. For some, the mill was a tool of oppression, but for others the toll was a price worth paying for greater economic efficiency, a potentially superior product, or simply to allow for larger quantities of grain to be milled than could be managed domestically (Langdon Reference Langdon1994; Reference Langdon2004, 275–8; Lucas Reference Lucas and Walton2006, 96–103). Suit of Mill was particularly strong in northern England and on the estates of religious houses. It was less enthusiastically applied in East Anglia and was never enforced in Kent, where traditional systems of land holding in severalty persisted after the Norman Conquest, giving peasant farmers an unusual degree of freedom and economic agency (Lucas Reference Lucas2012, 283).

Milling can be understood as a form of human/thing entanglement, in which objects are not ‘dead stuff’ but fashion human subjects even as they are manipulated by them (Robertston Reference Robertson2008). We can term these assemblages ‘bodies’, which are understood as more than flesh and bones (see O'Dell and Harris, this section); as relational compositions of the human and non-human. To follow Cohen (Reference Cohen2003, 43) bodies cease ‘to offer a circumscriptive home, becoming instead a volatile site of possibility and encounter’. This way of thinking about bodies as becoming through material engagement accords with medieval understandings of the body as defined by Walker Bynum (Reference Walker Bynum2011, 32–3), who states that ‘[a] medieval discussion of “body” is [a] discussion of “matter”’. Bodies are more than the person, they are generative and productive material processes. In other words, to think about medieval milling as human/non-human entanglement is to understand how this activity, and its associated tools, substances and spaces, were implicated in the becoming of diverse medieval bodies.

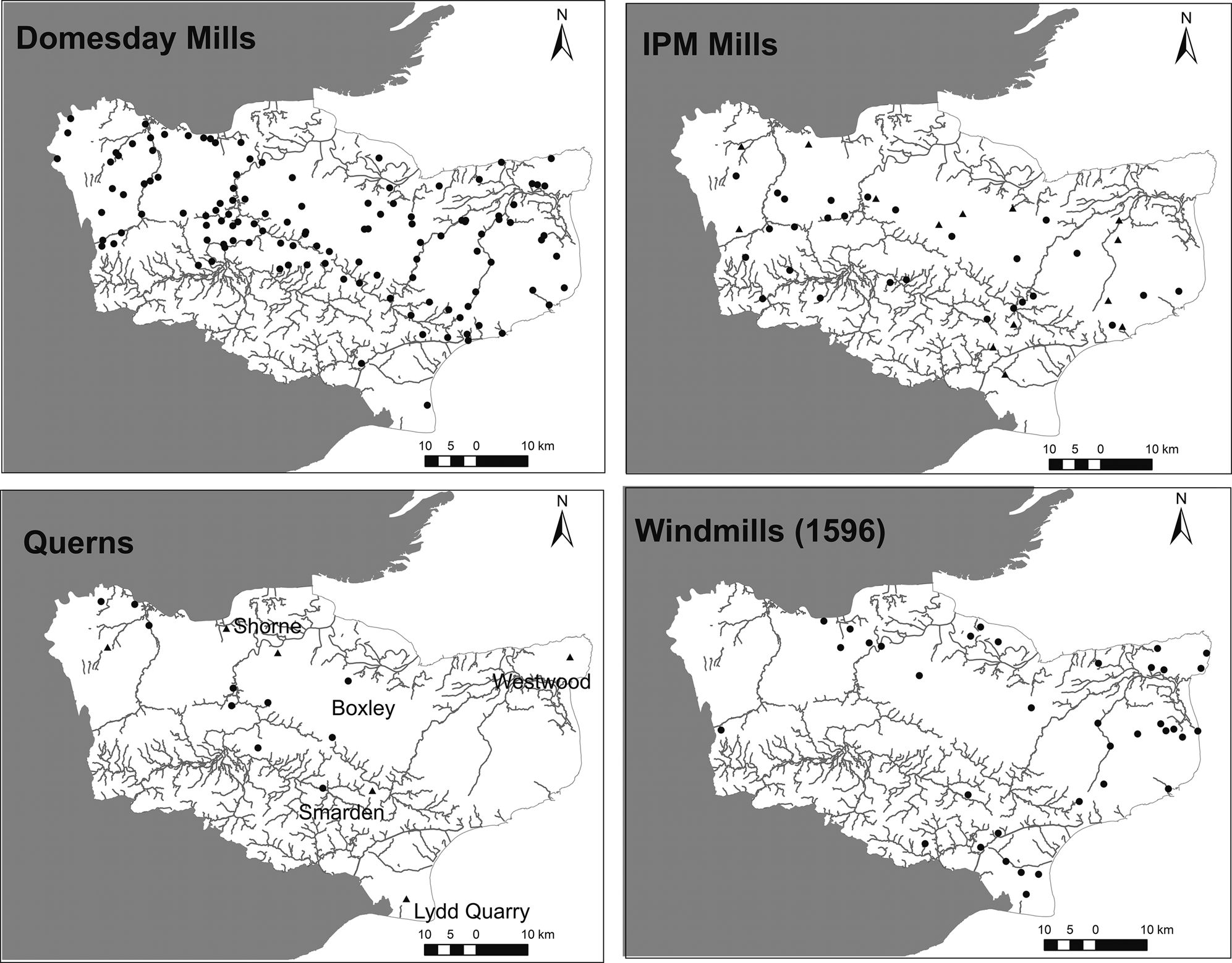

To return to Kent, the administrative arrangements summarized above already make it apparent that milling bodies emerged relationally. Their precarity or freedom in part emerged from regimes of tenurial or administrative control of what they could become. Kent provides an example of difference in medieval England, a place where custom deviates substantially from those elsewhere. At the macro-scale the landscape of Kent is one of linear mechanization and progress. In 1086 there were over 350 watermills in Kent, the majority of these being situated on the land of Canterbury Christchurch Cathedral and the possessions of the Bishop of Rochester and Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (Coles Finch Reference Coles Finch1976, 29–31; Fig. 2). Estimates by Langdon (Reference Langdon2004, 12) suggest that the number of mills in Kent stayed relatively stable between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. Inquisitions Post Mortem (IPM), records of property produced on the death of a tenant in chief, dating to the first half of the fourteenth century, record around 26 watermills in Kent (Campbell & Bartley Reference Campbell and Bartley2006, 279–98). These records relate only to the lands of lay lords, so exclude the Canterbury estate, but do include those mills on land forfeited by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and granted to lay lords in the late eleventh century. From the twelfth century, windmills were established, with those on the Isle of Thanet being among the earliest in England (Holt Reference Holt1988, 172). While watermills are largely situated down the spine of the county on the fast-flowing rivers, windmills are principally situated in coastal areas, particularly on the Isles of Sheppey and Thanet and Romney Marsh (Fig. 2). Some watermills in these areas may have been converted to wind power. Compared to those areas of England where landlords compelled tenants to use mills, mill values (effectively defined by their profitability) were generally low in Kent (Campbell & Bartley Reference Campbell and Bartley2006, 292). No windmills are recorded in Kent in the IPMs dating to 1427–37, which do record that three watermills were in a state of disrepair (Tompkins Reference Tompkins and Hicks2016). However, Symonson's map of Kent, dated to 1596, records 39 windmills, around half of which are situated on what had been monastic estates before the dissolution (Coles Finch Reference Coles Finch1976, 134; Fig 2). The Domesday mills were likely to have been demesne mills, operated by ecclesiastical landowers. As the Canterbury estate stayed largely under direct cultivation, or was leased to monks associated with the priory (Mate Reference Mate1983), it is probable that those mills effectively remained in the hands of the landowner. Elsewhere, mills were often leased to tenants who operated the mills for cash payment, although IPM records suggest that this practice was rare in Kent (Campbell & Bartley Reference Campbell and Bartley2006, 285).

Figure 2. The distribution of Domesday mills; water- (circle) and wind- (triangle) mills in early fourteenth-century IPM records; querns from Escheators’ records (circle) and archaeological contexts (triangle); and windmills in 1596, in Kent.

There is evidence for a narrative of progress in some Kentish contexts, in which handmilling was replaced by mechanization through the Middle Ages. An illustrative example is the quern stones excavated from a bakehouse complex at Westwood on the Isle of Thanet (Powell Reference Powell2012). These chiefly comprise lava querns imported from the Rhineland; however, fragments of millstone grit and a coarse igneous rock may suggest the deliberate acquisition of stones of varying coarseness, or disruptions to the supply of querns requiring an alternative source. The density of bakehouses found through archaeological research, and their association with enclosures rather than settlements, would suggest that these were a part of the estate infrastructure. This bakehouse went out of use in the early thirteenth century, a period in which windmills were probably erected on Thanet (Holt Reference Holt1988, 172), both mechanizing and centralizing the process of milling. This mechanization may have accompanied increased demand for grain from local, metropolitan and export markets, with the monks able to exploit the high productivity of their estate (see Campbell Reference Campbell and Sweetinburgh2010).

Historical records provide an understanding of mechanized milling and suggest that it was widespread across Kent. However, other evidence makes it clear that handmilling persisted as late as the fifteenth century. This means that a linear narrative of mechanization as progress masks diverse experiences of economic development. Two sources are available to assess handmilling in later medieval Kent. Historical evidence comes in the form of lists of goods seized from felons for the crown by an official known as the Escheator. Analysis of a large sample of Escheators’ records, undertaken as a part of the ‘Living Standards and Material Culture in English Rural Households, 1300–1600’ project (see Briggs et al. Reference Briggs, Forward, Jervis and Tompkins2019; Reference Briggs, Forward and Jervis2021; Jervis et al. Reference Jervis, Briggs and Tompkins2015), shows that these items were seized only occasionally and within the sample all but three mentioned relate to a household from Kent (Table 1; Fig. 2).Footnote 1 Furthermore, the majority of these lists date to 1381, appearing in lists of goods seized from individuals executed for their role in the Peasants’ Revolt. Discussing the use of querns at Wharram Percy, Yorkshire, Sally Smith (Reference Smith2009) proposes households were engaged in active acts of resistance to the seigniorial control exercised through Suit of Mill. Similarly, in a well-known story the Abbot of St Albans, Hertfordshire, confiscated querns from his tenants, smashed them and formed them into a pavement (Justice Reference Justice1994, 136). In the context of the Peasants’ Revolt, it is tempting to relate the persistent use of querns to a narrative of resistance. However, the absence of Suit of Mill in Kent suggests that such an interpretation is not appropriate, and that it is reasonable to assume that, as suggested by archaeological evidence, querns were particularly common in Kentish homes. The Escheators’ jurisdiction was limited to those estates where lords had not been granted right of forfeiture, effectively removing the large monastic estates, which are also missing from IPM data, from the sample.

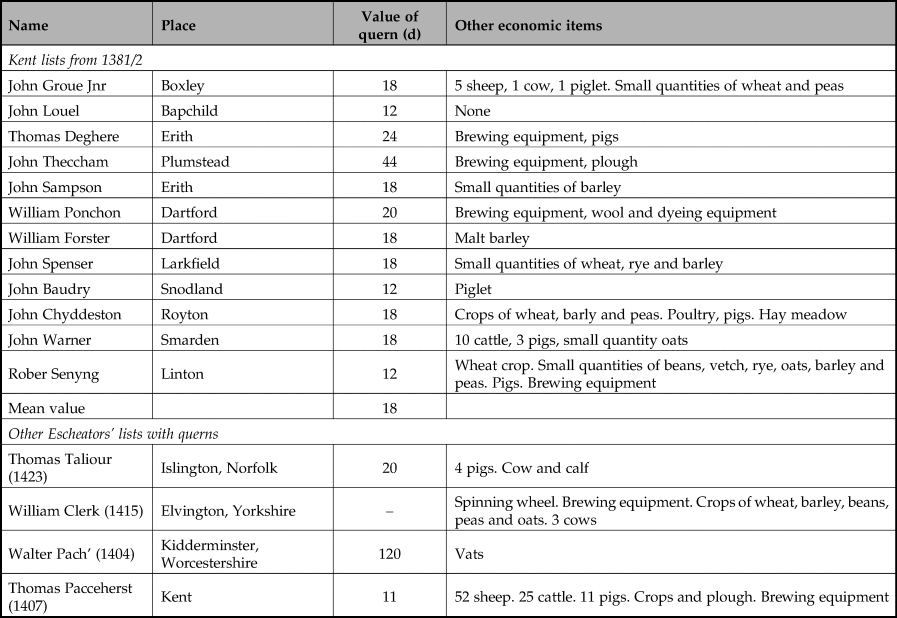

Table 1. Summary of Escheators’ lists containing querns.

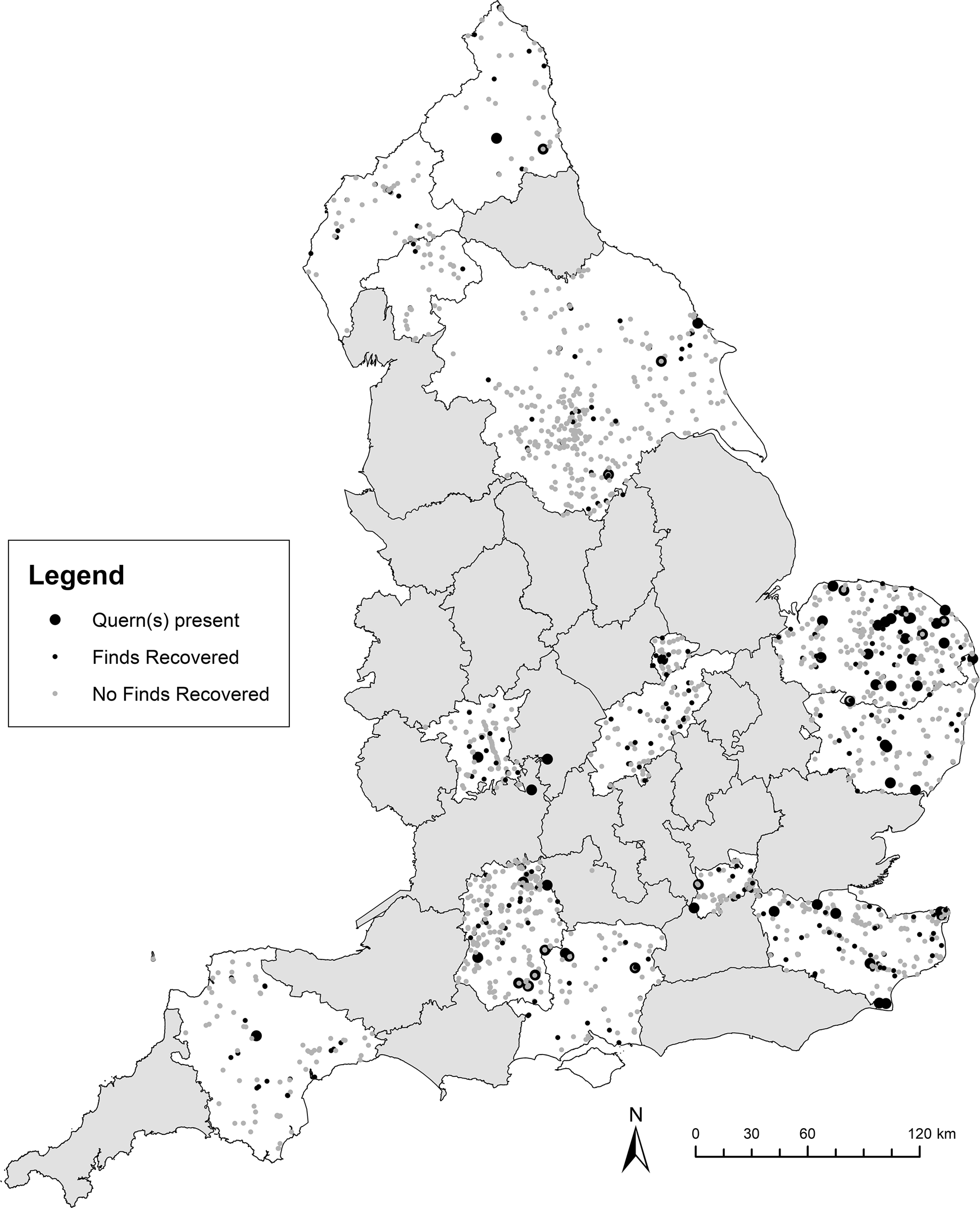

The second source is finds of querns from archaeological contexts. These occur across England, but are particularly common in Kent and East Anglia, mirroring the application of Suit of Mill (Fig. 3). These querns were considerable investments. The Escheators’ records show that they were typically valued between 1 and 2 shillings, roughly equivalent to a brass cooking pot or single items of bedding. Querns have been recovered from deposits associated with collapsed or demolished house structures (e.g. Barber & Priestly-Bell Reference Barber and Priestly-Bell2008; Gollop Reference Gollop2003; Holden Reference Holden2009; Saunders Reference Saunders1997). They were primarily imported, being lava querns from the Rhineland. These stones were widely sought after for their durability and grinding quality, being traded widely around the North Sea zone, having additional value in transport as ballast (Buckland & Sadler Reference Buckland, Sadler and Parsons1990, 230; Pohl Reference Pohl2010). Extensive quarries had been exploited since prehistory and multiple factors afforded their ability to be enrolled in the emergence of milling bodies in Kent. These range from the workability of the stone to its superior properties as a grinding stone and its low porosity, which made it relatively easy to transport (Major Reference Major1982; Pohl Reference Pohl2010). The extraction of these stones was itself bound up in local regulation and land ownership, with some quarries being operated by religious houses (Pohl Reference Pohl, Hansen, Ashby and Baug2015). The supply of querns provides a vivid example of how potential experiences of domesticity and economic participation spill beyond local frames, enfolding scales of relations across time and space. This reliance on imported querns also explains why they were not present in every home; the practicalities of supply and market demand created circumstances where some households were able to undertake milling, while others had to rely on milling services. When excavated the querns are extremely fragmentary, but their durability suggests that they could have been curated objects which served multiple generations, meaning that their acquisition was a long-term investment in household economy. This served to entangle past practice with emerging milling infrastructure, creating a tension between persistence and innovation. Given the economic freedom of Kentish households, it would seem likely that at least some households offered commercial milling services utilizing newly acquired or inherited stones. The development of milling infrastructure therefore shifted material relations, creating the potential for new or persistent bodies to emerge, variously entangled, or disentangled, from grain processing. Close analysis of the context of these stones reveals multiple narratives of progress, more complex than mechanization and the marginalization of domestic labour in milling.

Figure 3. The distribution of querns from archaeological contexts recorded by the ‘Living Standards and Material Culture in English Rural Households 1300–1600’ project.

Mapping milling bodies

Archaeological and historical evidence demonstrates the persistence of domestic handmilling in Kent into the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, despite the widespread presence of water- and windmills. A progress narrative would suggest that this activity was economically insignificant, and that those undertaking this work were economically marginal. Such a narrative de-values the role of domestic labour in the medieval economy, creating a false dichotomy between the domestic and economic spheres, what Rotman (Reference Rotman2006, 666) refers to as a ‘cult of domesticity’, a separate, private, female sphere set in opposition to the economic, public and male realm. An inevitable consequence of a progress narrative is the over-generalization and de-valuing of the economic contribution of women. Their labour was most commonly centred on the home, which was, in reality, the locale for the majority of medieval agrarian and artisanal production. The extent to which this labour was actually gendered is impossible to assess. While in general terms it is, perhaps, fair to surmise that male and female labour were not valued equally (Bardsley Reference Bardsley and Phillips2013), positing a simple binary between economically valuable male work and domestic female work presents an extreme view, which masks the diversity of gendered experiences of labour (Bennett Reference Bennett1996; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2009; Hanawalt Reference Hanawalt1999; Müller Reference Müller, Beattie and Stevens2013; Phillips Reference Phillips and Phillips2013, 125; Whittle & Hailwood Reference Whittle and Hailwood2020).

While archaeological evidence does not allow us to examine the gender of those undertaking this work, dissolving these false dichotomies provides a means of presenting an alternative, messier narrative in which economic intensification is not simply progress but entangled, varied processes of becoming (Crellin Reference Crellin, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020, 123–5). In acknowledging the gendered element of the bodies emerging through milling, my aim here is not simply to insert women into a narrative of progress, but to recognize that milling was one of many tasks through which multiple gendered experiences could emerge. A progress narrative, I argue, is one cause of an over-simplistic binary approach to gender roles which can be dissolved by exploring the material relations through which bodies emerged, and how relations (in this case legal restrictions) could also work to constrain the diversity of these bodies.

To begin thinking about these bodies we can examine some instances of households which engaged in milling despite seemingly having access to mechanized mills. At Shorne, in northeast Kent, lava quern fragments were associated with a thirteenth- or fourteenth-century structure (Gollop Reference Gollop2003). This household probably had access to a mill—a windmill was established by 1596 and it is this part of the county that was best served by windmills in the fourteenth century (Coles Finch Reference Coles Finch1976, 134). Shorne is situated in an area of fertile soil with high wheat yields. Here, then, a household seemingly invested in querns despite the availability of mechanized milling, with agricultural productivity providing the potential to undertake handmilling relatively intensively. A similarly illustrative example from the historical dataset is John Groue Jnr of Boxley.Footnote 2 Groue appears to have been a small scale agriculturalist, who had a quantity of wheat and peas. The mill at Boxley was part of the demesne of Boxley Abbey (Page Reference Page1926, 153–5), but Groue's possession of querns suggests that tenants were able to grind grain domestically. In contrast to Shorne, Boxley has fairly low-quality land and therefore grain yields are likely to have been fairly low (Campbell Reference Campbell and Sweetinburgh2010), suggesting that the use of the mill was uneconomical.

Rather than mechanization replacing domestic milling, these examples are suggestive of co-existing milling arrangements in quite different agrarian contexts. The local administrative and agrarian regimes created the potential for persistent forms of domesticity despite capital investment by landholders. In both cases the freedom of tenants to choose whether to pay a fee to use the mill created circumstances in which handmilling could persist and even for households to commodify their labour. This could be achieved by processing smaller quantities of grain than could economically be processed in wind- or watermills, or providing additional capacity seasonally. Rather than handmilling being evidence of households left behind by progress, these examples suggest a localized actualization of economy, emerging out of the situated relations of grain cultivation, processing and marketing. While at face value they provide evidence of domestic handmilling, the agrarian regimes imply these querns are indicative of different process of adaptation to local conditions. Langdon's estimate that 20 per cent of England's grain was milled domestically therefore conceals diversity in how this milling was organized and experienced, and the economic bodies which could emerge from it. These examples show how a concern with homogeneity and representation supresses difference. Our contemporary experience of mechanized and specialized production beyond the home causes us to write off the value of domestic labour and the diverse forms of becoming it affords (Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 118).

The ability for households to engage in handmilling, and potentally to commodify this labour, was the result of the specific administrative conditions in Kent. Elsewhere, Suit of Mill constrained the possibile forms of becoming which could emerge, restricting equivalent households to those at Shorne and Boxley from milling domestically. It can be understood as one of many patriarchal customs or laws which denied the potential of certain bodies to emerge. If we are correct in assuming handmilling was a largely female activity, it particularly restricted the forms of gendered body which could emerge as economic development was teritorialized into the household. We can identify a conflict between the capacity for multiple gendered bodies to emerge out of economic processes and the codingFootnote 3 of these bodies by custom and regulation, which limit becoming and impose, if not a gender binary, then a form of regulated gender difference. As the circumstances around the extraction and supply of querns from Germany demonstrates, these constraints could be local or the result of wider relations. Commerce, in the form of long-distance trade in stones and grain, was entangled in local environmental and administrative conditions in enabling or constraining the economic bodies which could emerge.

This supports Howell's (Reference Howell2008) concept of the entanglement of household and market as creating class-specific gendered divisions of labour, in which class might be considered a ‘coding’ variable which limits the potential forms of female becoming. Here we can look beyond class to explore how other factors intersected in the emergence of gendered bodies. The equation of female labour with domestic by-work marginalizes women in our narrative of economic development, but also limits the possibilities of gendered becoming which we might understand as emerging, or as being constrained from emerging, in the past. Crocker (Reference Crocker2019) has recently made a radical call for ‘feminism without gender’ in medieval literary studies. The crux of her argument is that a focus on reconstructing gender roles removes the disruptive potential of feminist theory in confronting illusory gender norms, trapping us in a constrictive binary (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013, 99). Rather, we can engage with difference by exploring the diverse ways in which querns, grain and mills were entangled in the negotiation of medieval bodies.

Specific contextual factors led to diverse experiences and encounters which facilitated or constrained the emergence of particular bodies. Once we acknowledge that milling played a role in the constitution of diverse bodies, mapping these tasks on to specific genders becomes less valuable than acknowledging that labour relations play a role in the emergence of differently gendered bodies. Regardless of whether all domestic milling was undertaken by women, the experience of those women was variable. The bodies which emerged were both unstable and precarious achievements. As households became increasingly reliant on the market, so the imperative for the commodification of labour grew. Some households became alienated from the processing of grain, relying on other households or employing milling infrastructure. In contrast, others were de-territorialized into the market for labour and grain, simultaneously creating opportunity and risk. For example, in 1381 John Warner, who lived in the village of Smarden, which does not appear to have been served by a mill, had his goods seized.Footnote 4 Warner's household is unusual in that in addition to the land held in his name, his wife Alice held two acres of freehold land, probably a consequence of local inheritance practices. Warner held a small number of cows and pigs, and it is possible that arable agriculture was undertaken on the land in Alice's name, which does not appear to have been subject to seizure. The possession of handmills is indicative of domestic-scale milling. If, as the list of Warner's possessions suggests, the household was not engaged in intensive crop production, it may provide an example of a household commodifying domestic labour by offering milling services. This drew the household into wider process of agrarian intensification and commercialization through adapting existing domestic tasks. The seizure of querns as a response to the rebellious actions of Warner provides a vivid indication of the precarity of the bodies constituted through the use of relatively scarce specialist tools, particularly if these were primarily used by Alice but were seized as the legal possessions of her husband.

Following Tsing (Reference Tsing2015, 134), the households of Warner, Groue and that at Shorne provide evidence of livelihoods that are ‘simultaneously inside and outside of capitalism’, where capitalism is understood as a means of ‘concentrating wealth, which makes possible new investments, which further concentrate wealth’ (Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 62). Investment in querns was a means of concentrating a specific form of wealth creation (the commodification of domestic labour), while mechanized mills performed a similar task with greater capital outlay, but potentially greater return. Farmer (Reference Farmer1992) shows that the acquisition of a single millstone could exceed a mill's annual profit, limiting the possibilities for the establishment of new mills despite increasing demand for milling services. The declining value of mills through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as evidenced by IPM data (Tompkins Reference Tompkins and Hicks2016) demonstrates the inherent risks associated with the establishment of mills.

Commercialization did not, therefore, lead to a replacement of modes of production, but seeped into households, re-shaping relations and potential forms of becoming (Deleuze & Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari1984, 258). Handmilling in domestic contexts might be understood as a form of ‘maintenance activity’ (see Montón-Subías & Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2018, 462)—the kind of everyday task which often provide anchors for continuity and a medium for resistance. The evidence for milling is suggestive, on the one hand, of these maintenance activities mediating persistence in household rhythms, but on the other, of the adaptation of these rhythms as the household was de-territorialized into a web of commercial interactions. The persistent use of querns was a means of adaptation, not of resisting the capital investment in mechanized milling, but of salvaging elements of domestic production and articulating them differently. Milling bodies were vulnerable bodies, due to the de-territorialization of persistent acts into commercial networks which created competition between mechanized and domestic milling and took household milling beyond subsistence.

The importance of contextualizing evidence for handmilling is further demonstrated by the archaeological evidence from Lydd Quarry on Romney Marsh. Here, evidence demonstrates that commercialization did not only drive mechanization, but also intensified the volume of international trade. The excavated evidence suggests increased availability of German lava querns in the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries, where local sandstone had been used previously (Barber & Priestly-Bell Reference Barber and Priestly-Bell2008, 206). The site at Lydd comprises a landscape of dispersed farmsteads on reclaimed marshland. The community were involved in arable and pastoral production, as well as fishing. Imported pottery, as well as the querns, provide strong evidence for market engagement with local ports. The nearby port town of Lydd was served by two windmills by 1596 (Coles Finch Reference Coles Finch1976). However, through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the archaeological evidence suggests that this comparatively isolated rural community retained a degree of self-sufficiency, processing grain domestically. As Rotman (Reference Rotman2006) argues for a nineteenth-century American context, activities took place in a range of locations within and outside the home and beyond the settlement, meaning that the lives of men and women in the community cannot be simply reduced to economic or domestic spheres. Sweetinburgh's (Reference Sweetinburgh2006) analysis of later medieval Kentish fishing communities demonstrates the strong communal bonds which developed through the manning of boats. There was a gendered element to labour around fishing, with men going to sea and women repairing nets and sails, as well as processing the fish. Communities of practice developed through fishing, as well as the pooling of labour in cultivation and perhaps the care of animals, creating a distinctive regime of household and communal labour within this coastal settlement. Domestic grain processing was a part of this process of community building and maintenance, with some households perhaps undertaking milling as others worked on the repair of boats or fishing equipment. Rather than viewing the community at Lydd as isolated from technological developments, handmilling should be understood in the context of the gendered communal relations which emerged from living in this environment. Critically, these activities blur the distinctions between domestic and economic, as households became entangled in, and intersected by, wider communities.

Querns were not only associated with the grinding of wheat, and the Escheators’ records from northern Kent, largely associated with small towns, provide an alternative perspective. These typically occur alongside brewing equipment, rather than the agricultural produce and tools found in lists from the southern and eastern parts of the county (Table 1). These querns were probably used for grinding malt, either the product of the household or acquired commercially. Brewing, like handmilling, is an activity commonly associated with women. Judith Bennett's (Reference Bennett1996) analysis shows that in the fourteenth century the brewing industry was dominated by small-scale female brewsters, but by the sixteenth century it was largely in the hands of male specialists. Interpreting this pattern, Bennett proposes that as brewing became more profitable, and opportunities for entrepreneurship emerged in the post-Black Death economy, women became marginalized, forcing them to adapt and find new ways of contributing to household income (Bennett Reference Bennett1997). Whether used for grinding grain or in brewing, as commerce intensified querns provided new possibilities for domestic labour and household economy, yet at the same time, the forms of domestic becoming in which they were implicated were precarious, with a range of contextual factors determining their ability to endure.

The changes in the organization of the brewing industry, as well as the ultimate domination of milling by mechanized mills, demonstrate how the bodies formed through domestic handmilling were precarious accomplishments. Although Suit of Mill was not enforced in Kent, it was elsewhere, the effect being to drive technological development and efficiency which eventually became territorialized into household economies. The fact that development was driven not only by administrative concerns but by desire for profit and efficiency in a rapidly commercializing economy is demonstrated by the presence of early windmills in Kent, where tenants were not compelled to use these facilities. Voss (Reference Voss2018, 289) has recently discussed how precarity is a ‘politically induced condition’—a historical condition which ‘depends on events that have already occurred and that shapes events that may or may not come to pass’. Here, then, precarity was the product of multiple spheres of political interaction, localized enforcement of Suit of Mill or freedom to adapt domestic milling and political conditions which stimulated and facilitated trade. Bodies are what Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, 46–7) term molecular becomings: they are not static, but productive and unstable. The territorialization of querns and grain into bodily performance was also the territorialization of their wider relations, an enrolment of patriarchal custom into the assemblage which created bodily tension, pulling bodies apart from the inside. In Kent, this latent potential was supressed by the greater freedom of peasant households, but economic intensification can be understood as bringing about what DeLanda (Reference DeLanda2016, 76) terms a phase transition, of reaching a critical point of incremental change which blows these bodies apart from inside. We can find a parallel with Haraway's (Reference Haraway1991, 166) argument that in the modern industrialized economy the workforce has become ‘feminized’, increasingly marginalized by technology and turned in to a ‘reserve’ labour force. Here we can observe a two-stage process, as agricultural intensification arguably commodified domestic labour through the commercialization of handmilling, only for capital investment in mechanized milling to supress the potential forms of becoming which could emerge from these productive relations. These examples show how the bodies emerging with grain production were territorializations not only of household organization, but of wider relations with markets, geology and climate. Understanding bodies as formed in this way allows us to move away from a simple binary distinction between male and female labour, to understand potential and diverse forms of gendered becoming (Braidotti Reference Braidotti1994, 158). Commercialization changed the constitution of bodies; it afforded opportunities to become otherwise, but also enfolded barriers to becoming.

Conclusion: a patchwork of affect

Bodies are patchworks of more-than-human relations. By focusing on the relations around the grinding of grain, it becomes possible to critique binary perceptions of labour and challenge narratives of economic progress. Approaches which characterize domestic labour as by-work trap us into considering the past in binary terms, as a pre-conditioned gendered binary. This extends to a false dichotomy between domestic and economic and under-values the role of domestic labour in driving the economic intensification of the Middle Ages. An approach centred on material relations goes further, highlighting how a narrative centred on progress masks variability in the relations between households and these things. Such a narrative masks the messy intersections of scale and space through which households and commerce were entangled. Simple analysis of the distribution of the contexts in which querns occur undermines an approach predicated on a linear narrative of progress. They reveal querns as enrolled in strategies of adaption; they become a tool for confronting capitalist and commercial growth, not necessarily to resist it, but to draw it back into alternative forms, for example by commercializing domestic milling. This is not a straightforward progression from domestic production to mechanization, but a messy entanglement of temporalities (agrarian cycles, the permanence of mills and the erection of new ones, household rhythms, the erosion of querns) where household and mill negotiate with each other. The answer to understanding medieval economic development does not lie in teleology—in plotting developmental points to a known end—but to mapping this temporal messiness.

The adoption of a perspective which sees medieval bodies as relational processes of becoming opens up possibilities not only to challenge linear ideas of progress, but to understand the kinds of bodies that emerge from, or are constrained by, changing material relations. Commercial growth and capitalization were not experienced evenly. A focus on domestic labour reveals how households negotiated vulnerability and were affected differently as they were enfolded into wider networks, and how medieval bodies emerged through entanglement with a growing world of things. We can understand the precarity of medieval bodies as the product not only of change, but as emerging from enfoldings of multiple temporalities. Rather than focusing on ‘progress’, we can perceive the medieval economy as a patchwork of affective relations, out of which new forms of becoming emerged.

Acknowledgements

This paper is developed from research seminars presented at Durham and Stanford Universities and I am grateful for feedback received at these events, as well as in the New Feminisms? session at TAG 2019. The data are derived from the ‘Living Standards and Material Culture in English Rural Households 1300–1600’ project funded by the Leverhulme Trust and were collated by the author, Dr Chris Briggs, Dr Alice Forward and Dr Matt Tompkins. I am grateful to Dr Rose Broadly (Kent HER) and Dr Rachel Crellin for assistance in the preparation of this paper.