The early development of the global match industry, between the 1860s and 1930s, is considered to have been dominated by the Swedish Match Co., particularly by Ivan Kreuger and the dominant position he created for his business in many world markets at the beginning of the twentieth century. Among other aggressive strategies to eliminate competition, this position was initially secured through pathbreaking technological innovations that enabled firms to achieve economies of scale and scope in production and to manufacture uniform products. The Swedish match industry became highly internationalized, enabling unique positioning for its high-quality products.Footnote 1 In contrast, accounts of the development of the Japanese match industry, which developed around the same time (the Meiji period in Japan), tend to highlight that the industry was highly fragmented, produced low-cost goods of non-uniform quality, incorporated little mechanization, and relied essentially on intensive labor, low wages, and low-priced matches.Footnote 2 This study challenges these views, arguing that the Japanese match industry not only was a major global challenger of the Swedish match industry but also achieved international competitiveness, but that it did so through a combination of low cost, low price, and differentiation strategies. “Differentiation” is used here to refer to the ability of firms to offer products that customers perceive as unique.Footnote 3 It is one of the strategies that firms can use to grow, as an alternative to low cost production.Footnote 4 As argued here, the Japanese match industry provides early evidence that it is possible for firms to achieve international competitiveness through a combination of these strategies.Footnote 5

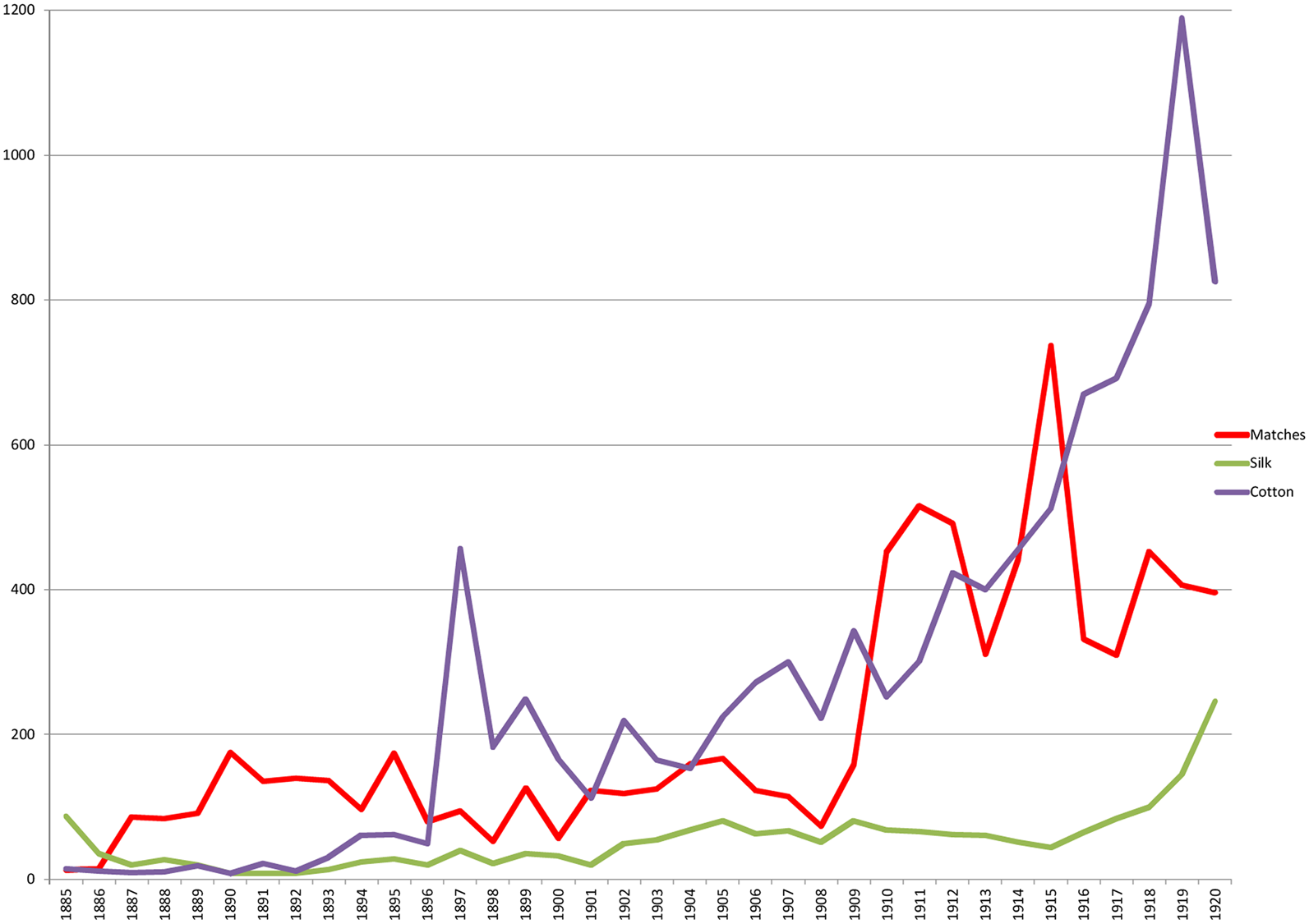

The study addresses the following questions: How did the Japanese match industry achieve global competitiveness by relying on strategies that combined low cost and low price with differentiation? Were Japanese match producers followers of the Swedish match industry, as argued in the existing literature, or were they instead challengers? Why did the Japanese match industry develop so rapidly between the 1860s and 1930s in terms of production and exports? Who were the entrepreneurs behind the creation of this industry in Japan? Did the development of the match industry impact the development of other, related industries in Japan? The period under analysis, from the 1860s until the early 1930s, is one during which a modern industry of safety match production emerged in different countries, global competition increased, and consumption of safety matches spread to entire populations irrespective of income. The study draws extensively on original trademark data and other industry and trade statistics. Trademark data has been acknowledged to be a reliable proxy for differentiation and marketing innovations by firms.Footnote 6 Curiously, between approximately 1868 and 1930 the Japanese match industry had the largest number of trademark registrations in Japan—higher than the silk and cotton industries, which were the most important exports from Japan during that period (see Appendix 1). Japan was also by far the largest exporter of matches in volume in the world. For instance, between 1912 and 1923, Japanese exports of matches amounted to more than the exports of the next twelve largest countries altogether, including Sweden.Footnote 7

This article is organized in five parts. Following the introduction, section two provides an overview of the early evolution of the global match industry. Section three explains the development of the Japanese match industry from the Meiji to the Taishō and Shōwa periods, highlighting its structure and dynamics and also the strategies followed by the main firms. Section four explains the success of the industry beyond low-cost-production explanations and highlights other sources of competitive advantage associated with differentiation through branding, trademark registrations, and innovative graphic design and packaging, as well as total quality control of products that would otherwise be undifferentiated. Finally, section five provides some conclusions.

The Origins of the Global Match Industry, 1870–1930

The production of safety matches on a large scale began in the early 1860s with new technological developments that both enabled the automation and standardization of production and improved quality.Footnote 8 Soon matches became a convenience product available to all, providing a simple, quick, clean, and efficient means of ignition. They were also invaluable to the tobacco industry, which was developing around the same time.Footnote 9 In 1903, an important change took place in Sweden that radically transformed the domestic industry structure and the dynamics of the global industry. The seven largest Swedish match factories amalgamated into one company, under the name Jönköping and Vulcan Match Co. A further wave of amalgamations took place in 1917 involving the whole industry, leading to the formation of a monopoly, the Svenska Tändsticks AB (Swedish Match Co.), with Ivar Kreuger as president. These mergers were associated with strategies aiming not only to increase economies of scale and scope in production and distribution but also to achieve global dominance and deal with pressures from foreign competition, in particular, from Japanese match producers.Footnote 10

Soon after it was formed, the Swedish Match Co. embarked on very aggressive processes of further mergers and acquisitions in foreign markets, obtaining dominant positions in many countries.Footnote 11 Japan eventually was targeted by the Swedish Match Co., a few years before it went bankrupt. It all ended in 1932, three years into the Great Depression, when Kreuger's holding company, which controlled the Swedish Match Co., showed deficits for the match business around the world exceeding the national debt of Sweden. Kreuger's accounts had been hidden with the reporting in the financial accounts of fictitious assets, and with the creation of a maze of over four hundred subsidiary companies around the world. Later that year, Kreuger committed suicide.Footnote 12

While it is well established that Sweden was the industry leader during this period, there were other competitor countries besides Japan. Austria produced slightly inferior and cheaper matches but was also an international exporter; Germany and France were distinctive for having government monopolies on the production of matches; Belgium, Holland, and Russia were small-scale producers. Britain had local production but also relied on imports of matches from Sweden, Belgium, and Japan and was a re-exporter to North America and Australia, among other parts of the British Empire.Footnote 13 In the United States a monopoly was established in 1881 by the Diamond Match Co., which was the result of the merger of the oldest and largest match companies in the country. Despite its large size and monopoly power the Diamond Match Co. was unable to meet the domestic-market demand, thus creating opportunities for foreign producers, such as Swedish and Japanese match manufacturers. Japanese match firms were particularly successful in selling to the United States during World War I, while the Swedish Match Co. was prevented from competition because of the war. The situation changed in the 1920s when the Swedish Match Co. entered the United States, first through a ten-year strategic alliance with the Diamond Match Co. (and its associated companies). This alliance allowed the Diamond Match Co. to become the sole agent for Swedish strike-on-box matches. However, soon after the alliance was formed, Kreuger made multiple attempts to take over the Diamond Match Co. and gain control of the U.S. market. He eventually succeeded in doing so in 1932.Footnote 14

In Asia, Japan was the main producer of matches. China was, for a long time, essentially a consumer of Japanese matches; however, from 1908 a local Chinese industry developed as a result of the first anti-Japanese boycott against Japanese goods. New match-producing firms were established in China, which used softwood imported from Japan. Some of these newly formed businesses were foreign branches of Japanese match manufacturers, including the Japan China Match Manufacturing Co., owned by Japanese entrepreneur Kousaka Manbei.Footnote 15 Another example is Hankow Co., established in 1897—a branch of the Japanese match firm Ransho Co., which grew to become the largest match factory in China by 1910. These companies basically produced matches to serve the Chinese market. Other Sino-Japanese incidents and boycotts followed, leading to a gradual decrease in the exports of Japanese matches to China. It all culminated in 1928 with an abrupt slump in exports as a result of protective barriers created by the Chinese government against Japanese imports.Footnote 16 India was another important consumer of Japanese matches, only developing its own match-producing industry from the 1920s.Footnote 17 Before then, India had very few match factories, so most matches consumed were imported. For instance, in 1910 there were only six match factories in the country, the market leader being the Bombay Match Co. Indian match entrepreneurs had insufficient capital and inadequate management skills and were only able to produce poor-quality and high-priced matches.Footnote 18 Before World War I, Sweden and Japan competed globally but tended to operate in distinct markets; India was the main market in which they competed directly. However, during World War I, Japan captured almost all the trade in that market, as a result of the difficulties experienced by the Swedish Match Co. in obtaining freight from Europe. Japanese match exports also targeted southern Asia during World War I. Saigon was a significant market of destination for Japanese matches, but most of the Japanese matches sold in this market were re-exported from Hong Kong.Footnote 19After the war, the establishment of local match industries in India and China and the keen competition of the Swedish producers greatly curtailed Japanese match exports.Footnote 20 From the early 1920s, the Indian match industry developed rapidly. By the early 1930s, domestic production accounted for most of the consumption in India. An important factor in this phenomenon was the prohibition by the Indian government of the sale of sulfur matches, which were being produced and exported by Japanese match producers for the Indian market. In response to this new legislation a number of Japanese match factories switched to sulfur-free matches for export to India.Footnote 21

The Opening of the Japanese Economy and the Development of the Match Industry

Early development of the industry and its industrial clusters. The Meiji (1868–1912), Taishō (1912–1926), and Shōwa (1926–1989) eras opened the Japanese economy to the Western world.Footnote 22 Until the 1860s Japan was a closed economy, with weak institutions, poor infrastructure, and underdeveloped capital markets, and it was far behind Europe and North America in technological terms. Many Western countries had by then completed the first Industrial Revolution and were starting the Second Industrial Revolution, developing big business, mass production, and mass marketing.Footnote 23 This gap between Japan and the more advanced countries in the West is considered to explain a phenomenon known as “organized entrepreneurship” in pre–World War I Japan, meaning that many entrepreneurial initiatives were community centered, associated with a clear sense of public good and national emergency.Footnote 24 The first stage of Japan's industrialization is considered to have taken place through commerce, rather than through technological innovation and processes of reorganization of industry, as most labor was until then dedicated to agriculture or handicrafts.

Before the opening up of Japan to the rest of the world in 1868, flint and steel were used locally for ignition. A few matches were imported from Europe but were only affordable to the wealthiest Japanese.Footnote 25 The safety match was first produced in Japan by Makoto Shimizu, who had formerly been a samurai.Footnote 26 In 1875 Shimizu established a pilot factory in Tokyo. The following year, he established a larger factory after having raised share capital in the form of a loan granted by the government.Footnote 27 Simultaneously, Shimizu shared his production processes and knowledge about match manufacturing with other former samurai who had lost their jobs as warriors. Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868 these samurai, who had traditionally been members of a powerful military caste since feudal times, had to redefine their activities, and many became entrepreneurs. They had both the administrative skills required for establishing new businesses and the networks that enabled them to share knowledge and physical assets. The availability of skillful entrepreneurs, along with the practically nonexistent barriers to entry, allowed many new entrepreneurial initiatives to develop in the match industry during this period.Footnote 28

Former samurai entrepreneurs were able to raise capital for their new businesses in several different ways, which included loans granted by the government, the issuing of shares, and loans from trading companies, many of which were owned by Chinese merchants.Footnote 29 A few match manufacturing businesses developed within prisons. An illustration is the match factory in Hyogo Prison which was financed through the issuing of shares. There were several small and medium-sized match factories in Kobe, such as Yoshitomo Honda Co. and Ginbee Hata Co., and also Sadajiro Inoue Co. in Osaka, which were established relying essentially on loans from foreign merchants. While several of these newly established businesses went bankrupt within a short period of time, many survived. Meiji entrepreneurs regarded the social gain as more important than private profits, which explains the endurance and perseverance under hardship by some of them that eventually led to success.Footnote 30 By 1895 there were 210 match-producing factories in Japan. In that year, the prefectures of Hyogo (with 52 factories) and Osaka (with 39 factories) accounted jointly for 44 percent of all the match factories in the country, 78 percent of production, and 83 percent of revenues in the Japanese match industry. The two prefectures developed as industrial clusters, becoming the leading producers of matches in Japan. Each of these two clusters comprised a group of similar and related businesses, which shared common markets (local and foreign), technologies, demand for skills, and infrastructures and were linked in multiple ways by networks sharing physical assets and knowledge. They also had similar levels of support from local governments.Footnote 31

The early success of the safety match cluster in Kobe (Hyogo Prefecture) is greatly associated with the large supply of cheap and available labor in that region, as well as the fact that it was one of the port cities through which foreign matches were imported when the country first opened for international trade. Large numbers of Chinese merchants had settled in Kobe, which, once Japanese production of safety matches started, also shipped these matches to southern China. At about the same time, Osaka also developed a match cluster, but its captive market was in northern China; the Chinese merchants who had settled in Osaka were largely from that region. The Osaka cluster specialized in the manufacture of a different type of match: the white phosphorus match. The high risks associated with its manufacture and use finally led to the framing of the Berne Convention of 1906, which bound the contracting countries to prohibit the manufacture, sale, or import of matches containing white phosphorus. Despite that, the Japanese manufacturing and exports of white phosphorus matches from Osaka continued until 1921. However, after 1913, production and sales started to decline, after new laws were introduced in India that prohibited the import of such type of matches into that market. This resulted in a disintegration of the Osaka match cluster.Footnote 32 In contrast, the Kobe cluster, which produced safety matches, continued to grow.

With the disappearance of the Osaka cluster some match producers moved to Kobe and developed new businesses for the production of safety matches. This allowed them to take advantage of their knowledge already acquired in the industry and of their proximity to a strong and expanding match cluster.Footnote 33 Some of the Chinese merchants - brokers and distributors, who used to export lucifer matches to northern China - also fled to Kobe to try to keep their businesses alive by exporting safety matches to their existing clients/markets. This led to an even higher concentration of production and exports of safety matches in the Hyogo district. Around the same time, some Japanese firms also chose to amalgamate with Chinese distributors as they controlled the trade and distribution with China, which was one of the most important markets for Japanese matches.Footnote 34 The development and strength of the cluster in Hyogo relied on the efforts of a range of stakeholders. Moving backward in the value chain, stakeholders included suppliers of timber such as wood traders, stick merchants, outer and inner packaging merchants, suppliers of chemicals, and label printers. Most of the timber was supplied by the Japanese government, which controlled the forests in Japan and sold it to match manufacturers at a price far below what competitors had to pay in other markets. Wooden match splints were made of Populus tremula (aspen), Tilia cordata, and Populus suaveolens. Before World War I this wood was mainly from Hokkaido, in the northern part of Japan, but by 1930 other regions were trading in these types of trees. For instance, the maritime province of Siberia was supplying about 80 percent of total splint used in Japanese matches made of aspen.Footnote 35

Moving forward in the value chain, stakeholders in the match industry were essentially exporters and foreign and domestic merchants.Footnote 36 Only a few large manufacturers were vertically integrated, with their own stock warehouses and trademark printing facilities and machinery.Footnote 37 A large number of merchants supplying matches to foreign markets were Chinese and Indian expatriate entrepreneurs who had settled in the Hyogo Prefecture (Kobe) and, until the 1920s, in the Osaka Prefecture. They played an especially important role in the development of the industry and its international competitiveness. By 1911, for example, 83 percent of the matches exported to China were handled by Chinese merchants and 70 percent of matches exported to India, especially Mumbai (Bombay), were shipped by Indian merchants. Japanese merchants made up the remainder of exports to these markets.Footnote 38

Over time, and before the takeover of the main Japanese match producers by the Swedish Match Co., some Japanese match producers merged and integrated forward, becoming international traders. Others were acquired by economic groups (zaibatsu) that were already internationalized. The newly established companies, known as the big four, were the Nippon Match Manufacturing Co., Toyo Match Co., Chuo Match Co., and Teikoku Match Co.Footnote 39

The international trade of Japanese matches

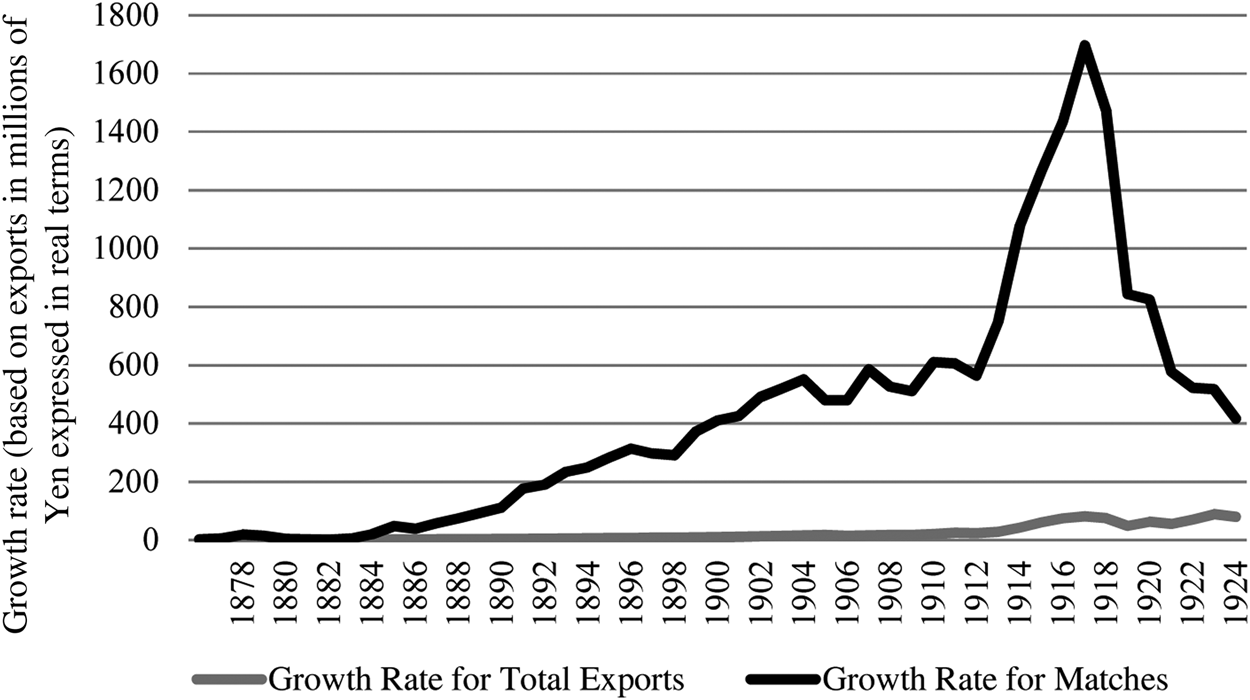

The first effort to organize international trade in Japan took place in the early 1880s with silk and cotton.Footnote 40 Between 1878 and 1924 these two industries accounted for the majority of Japanese exports, corresponding to 34 percent and 19 percent, respectively; green tea came third, contributing 2 percent; and matches came fourth, corresponding to 1 percent of total trade for that period.Footnote 41 Most of the research on Japanese international trade and the openness of the country during this period tends to focus on the first three industries—silk, cotton, and green tea.Footnote 42 Nonetheless, the global match trade grew, on average, at a far greater pace than the average exports for Japan during that period (see Figure 1). While not very significant in value terms, the Japanese match industry developed very quickly and became a major world producer and exporter from the Meiji period until the 1930s, contributing to the improvement of the country's overall balance of trade.Footnote 43

Figure 1. Growth rates for match exports and for total exports from Japan, 1878–1924. Note: Growth rate is based on amount states in millions of Yen expressed in real terms. (Source: Tax Bureau, Ministry of Finance, Foreign Trade Outline: 1878–1926 [Tokyo, 1878–1926].)

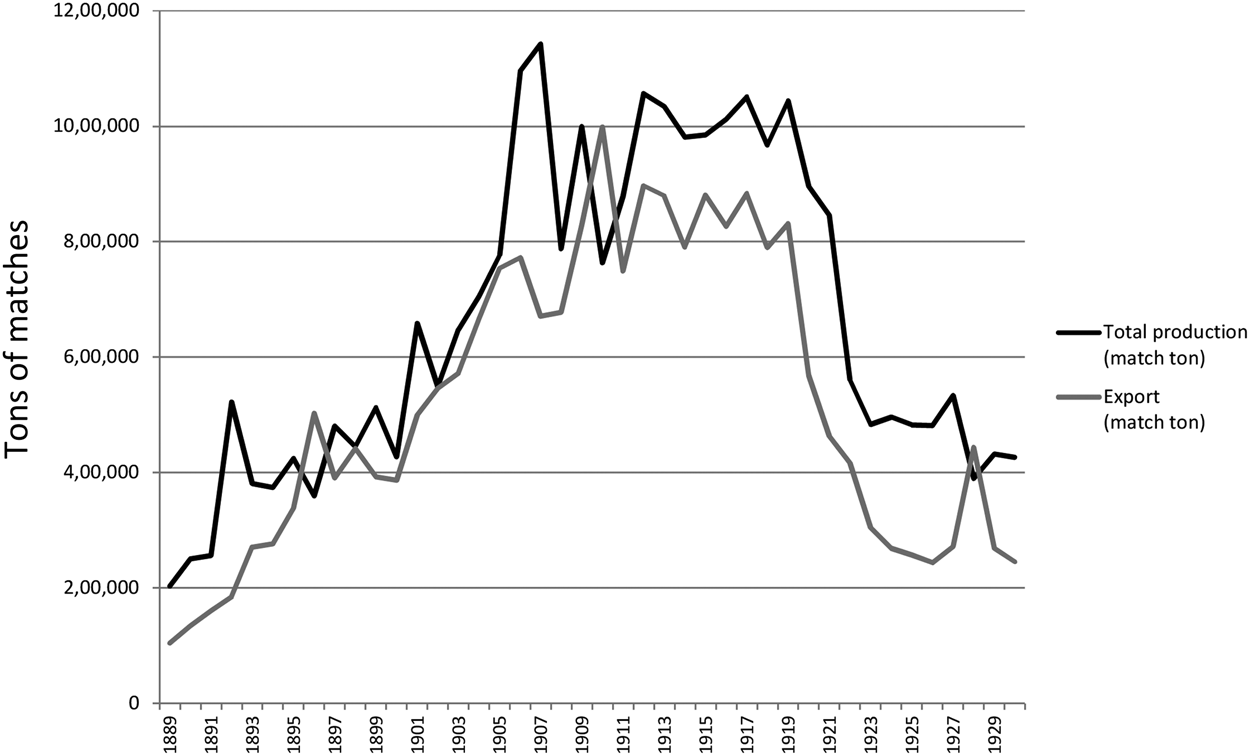

Having started to produce matches in 1878, Japan had become self-sufficient by 1880 and no longer needed to import matches from foreign markets.Footnote 44 Apart from China and India, important export markets included Hong Kong and Korea. Other markets, less significant included the United States, the Philippines, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. By 1913, exports to Hong Kong, China, Korea (until 1910 when Korea is annexed by the Empire of Japan until 1945), and British India accounted for about 90 percent of all matches exported. While China and India declined dramatically as main markets after 1910, for the reasons previously mentioned (China's boycotts on Japanese trade and the development of a local industry in India), other markets increased rapidly, particularly Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. Figure 2 compares the evolution of total exports and total production of matches from 1889 to 1930 in match tons (1 match ton = 7,200 ordinary matchboxes). The volume of matches exported shows a similar trend to that of overall production. On average, exports corresponded to more than 70 percent of total production between 1893 and 1919, indicating the Japanese match industry's strong reliance on overseas markets.Footnote 45

Figure 2. Total Japanese production and export of matches, 1889–1930. (Source: Japan Match Industrial Association, ed., Statistical Abstract of the Match Industry [Hyogo, 1965].)

After World War I, production and exports experienced a rapid decline. A loss of international trade resulted from the fact that the main importing countries, China and India, had by then established domestic match-producing industries. Additionally, many Japanese match producers based in the Osaka cluster relied on old forms of producing matches—that is, phosphorous matches—and, unable to modernize, ending up going out of business. While in 1900 there were about 189 factories in Japan, by 1935 this number was only 89. A similar pattern can also be observed in the number of workers, which in 1895 was 35,400 and by 1935 had decreased to 8,000.Footnote 46 Some manufacturers had huge stocks of matchboxes and labels used exclusively for yellow phosphorous matches and were not able to dispose of them before the prohibition of lucifers became effective.Footnote 47

Between 1924 and 1927 the Swedish Match Co. entered the Japanese market, taking over a series of leading local match producers. In 1924 it bought the Nippon Match Manufacturing Co., then the second-largest match company in Japan. This company was partly owned by Mitsui & Co. (with 25 percent of share capital). Mitsui & Co. was a leading economic group that had developed during the Meiji era as an international merchant of commodities, becoming the first Japanese multinational enterprise.Footnote 48 Subsequently, in 1927 the Swedish Match Co. purchased the majority of shares of Daido Match Co., then Japan's largest manufacturer of matches. Among other subsequent mergers and acquisitions, the Swedish Match Co. also acquired Asahi Match Co. (based in Kobe-Hyogo). By the end of 1927 the Swedish Match Co. controlled over 73 percent of Japan's match exports worldwide and 81 percent of sales in the Japanese market.Footnote 49 Despite eliminating domestic competition, these mergers and acquisitions in Japan introduced new and more advanced machinery, which increased mass production and the ability of Japanese firms to obtain economies of scale and scope. In 1928 the Swedish Match Co. began dramatically cutting the volume of matches exported from Japan, clearing the way for its affiliates to expand their businesses in other parts of the world, particularly those based in eastern European countries. Between 1928 and 1931, exports from Swedish-controlled companies based in Japan were reduced by three-quarters.Footnote 50 When the Swedish Match Co. went bankrupt in 1932, the Japanese match companies that survived were acquired by Japanese economic groups. For example, the Daido Match Co. was acquired by Aikawa Yoshisuke Co. of Nissan Zaibatsu; in 1939 the Daido Match Co. merged with Nissan Nohrin Kogyo Co. However, these mergers and acquisitions by Japanese economic groups were not enough for the Japanese match industry to recover its former international competitiveness.Footnote 51 Various events such as the Manchurian Incident of 1931, the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, and the Asia-Pacific War beginning in 1941 further aggravated the international trade of Japanese markets, eventually leading the Japanese government to take control of the production and distribution systems in place in the match industry.Footnote 52

Combining Strategies of Differentiation and Low Cost

The development of the Japanese match industry during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is usually attributed to two factors: low labor costs and geographical location. The first argument is that the industry in Japan relied on low labor costs and low cost of raw materials, in particular timber, which was subsidized by the Japanese government.Footnote 53 When compared with other countries such as Germany, Britain, and the United States, labor costs in Japan were substantially lower. The implicit argument is thus that quality had to be lower.Footnote 54 Another argument is that Japan benefited from a privileged geographical location, as it was closer than its major competitors to two important consumer markets, China and India, and these two markets only developed their own match industries relatively late. High freight charges significantly increased the prices of European matches exported to these two markets, especially China, making it hard to compete.Footnote 55 The branding and marketing skills developed by Japanese match producers are absent from such arguments. Because Japanese match manufacturers were unable to compete based on technological innovation and economies of scale and scope in production, they invested instead in marketing innovation and related areas. This involved the creation of brands, the registration of all trademarks, and the protection of intellectual property through enforcement of the law, as well as innovations in graphic design and packaging that entailed standardization and adaptation of products and labels to host-country consumer preferences. The combination of these differentiated strategies with low cost and low-priced products put the Japanese match industry in the position of major challenger to the Swedish match industry in global markets. Another factor that enabled the competitiveness of the industry was the role of trade associations created essentially by private initiatives.

The role of trade associations

The period prior to World War I is known for the extensive support that the Japanese government provided to traditional industries, for example, through the creation of manufacturing and trading associations, with the aim of promoting exports and international competitiveness. Industries that benefited from such governmental support included silk, cotton, rice, pottery, and straw, among others.Footnote 56 Yet this was not the case with matches. The first trade associations in the match industry were the initiative of private entrepreneurs; nonetheless, they received support from the Japanese government.Footnote 57 Mitsui & Co. was central in the creation of the first match trade associations and the establishment of rules and codes of conduct to improve the international competitiveness of the industry. The match associations played a major role not only in the way the industry was organized and in its governance but also in the way in which the industry as a whole responded to emerging challenges and opportunities in global markets. The operations of the industry associations also reflected improvements in the Japanese institutional environment, in particular, changes in the enforcement of laws and regulations.Footnote 58

The Hyogo Match Manufacturers Association and the Osaka Match Manufacturers Association were the first match trade associations established in Japan in 1887. Soon after, in 1888, a new association, the Osaka and Hyogo Allied Match Manufacturers’ Association, was established to oversee and coordinate the activities of these two regional trade associations. The main objective was to protect match manufacturers from international horizontal and vertical competition—in particular, from the commercially aggressive Chinese merchants of matches—and to try to develop international match exports independently from them. The associations were particularly innovative in the way they investigated and regulated the use of trademarks, which, as established by the associations, had to be used on every single matchbox exported.Footnote 59 The registered trademarks also signaled to foreign countries—especially China and Southeast Asia, where there was no trademark registration system—that these products, legally protected, were non-imitable.

The trade associations created very thorough procedures for firms. All manufacturers had to be members of the association in order to operate in the industry. Before any application for the registration of trademarks, the association inspected the quality of all matches and their packaging, thus ensuring high standards despite their relatively low cost and low price. At the end of inspection, matchboxes had to receive a seal of approval by the inspection station. To ensure distinctiveness of each firm's portfolio of brands, each manufacturer could only register up to five designs associated with the trademarks registered for export products. No unregistered trademarks could be used on the products, and all designs had to be submitted and approved by the Allied Match Association before application for registration.Footnote 60 The Allied Match Association also had other roles, such as helping to resolve contentious issues associated with the activities of its members, including conditions for admission into the association and approval to operate in the industry.Footnote 61 Additionally, the Allied Match Association oversaw issues of imitation and fraud.Footnote 62 There were many cases of trademark holders who complained about the use of their trademarks by imitators in exporting countries, especially in those countries where there was no trademark registration system in place or where such a system was ineffective.Footnote 63 Over time, the power of the match trade associations increased, with the government granting these institutions more rights, such as the ability to directly oversee applications from new entrants in the industry.Footnote 64 Mitsui & Co., apart from being the main international distributor of matches—having partial ownership of a number of match-producing companies, such as Nippon Match Manufacturing Co. (where it placed two of its own managers as directors, Yoshikazu Iida and Kinichi Tomono) and being behind the creation of the first match trade associations—also provided loans to match manufacturers that were not in any way linked to Chinese merchants and traders. Additionally, this multinational enterprise offered other forms of support, for example, providing information and storage facilities for matches ready to be sold internationally. Some relatively large match companies that distributed their matches through Mitsui & Co. included Seisuisha Co. in Osaka, Masanosuke Naoki Co. in Kobe, and Manpee Kosaka Co. in Hiroshima. By 1914 Mitsui & Co. controlled about 20 percent of the Japanese match exports.Footnote 65

Branding through trademark registrations

The Japanese trademark registration system started in 1885, slightly later than in the most developed countries in the Western world.Footnote 66 It did not take into account intellectual property laws in other countries.Footnote 67 Neither the new law nor the procedures that came with its implementation impeded entrepreneurs from registering imitations of brands and labels; for example, the first registration of a match brand in Japan is a very accurate imitation of a label produced by the Swedish Match Co. Initially, the process of application for trademark registrations tended to be the responsibility of local governments and there were no coherent and coordinated criteria to be followed for investigation of these applications across the country. For instance, trademark applications could be rejected in Hyogo Prefecture and later accepted and registered in Osaka Prefecture, and vice versa.Footnote 68 As a result of the various deficiencies in the institutional system, many similar trademarks were registered in different prefectures, and that led to disputes among match manufacturers and between match manufacturers and exporters. The trademark regulations (Imperial Ordinance No. 86) enacted in 1888 aimed to deal with several of these deficiencies in the trademark legal system and to stop unproductive entrepreneurs from taking advantage of loopholes in the law. The new regulations required applicantions to be submitted to the National Patent Office directly, aiming to reduce the discrepancies and difficulties mentioned above relating to different local registration procedures among prefectures. In 1899, a new trademark law (Act No. 38) was enacted, more in alignment with the Paris Convention for the Protection of Intellectual Property, which had been adopted in 1883 and was the first major international agreement to help creators ensure that their intellectual property was protected in other countries.Footnote 69 In 1909, a new trademark law (Act No. 25) was enacted to further protect any attempts at imitation of original manufacturers’ trademarks by including specifications about “associated trademarks” and “coloring.” This system allowed applicants to register trademarks that were related or similar to their own, to prevent the registration of imitations.Footnote 70 However, it also led to a cluttering of the trademark register, as many trademarks were registered that were never meant to be used. It was only in 1921 that the Japanese trademark law reached a standard similar to that found in Western countries such as Britain and Germany. The new law enacted then required that the Patent Office publicize each application by placing a notice in the Official Gazette, allowing anyone opposing any particular application to do so before the trademark could be registered.Footnote 71

Despite all the fragilities of the Japanese trademark system in its first years, the number of trademark registrations increased sharply. In 1885 a total of 949 trademarks were registered in Japan (of which only 13 were matches). In 1897, foreign firms were allowed for the first time to apply for Japanese trademark registrations, accounting for 58 percent of total registrations. A total of 7,563 match trademarks were registered between 1885 and 1920.Footnote 72 In 1890 match trademark registrations represented 31 percent of all trademarks registered in the country, making it the class with the highest number of trademarks for that year. By 1920, a total of 124,069 different trademarks had been registered in Japan, with matches accounting for just 6.1 percent of total registrations.Footnote 73 The position of matches as a class in trademark registrations had dropped from first place in 1915 to thirteenth place by 1920, in line with the evolution of both exports and the production of matches relative to the fast development of other industries.Footnote 74

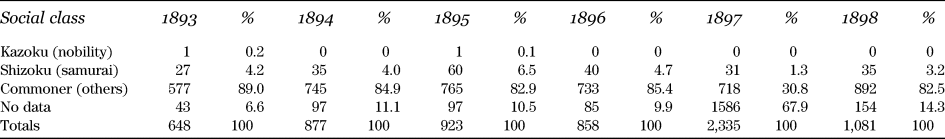

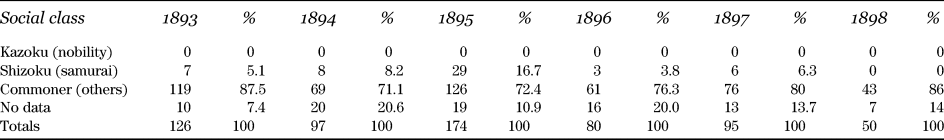

A particularity specific to the Japanese trademark registration system, and nonexistent in other countries such as Britain, France, the United States, Portugal, and Spain, was that between 1893 and 1898 all registrants of trademarks had to declare their social class when submitting an application. After the Meiji Restoration, the government created three social classes: kazoku (nobility), shizoku (former samurai), and commoner (others).Footnote 75 Tables 1 and 2, respectively, show the social class of applicants for all trademarks registered during that period and the social class of registrants of match trademarks.

Table 1 Social Class of All Registrants of Trademarks, 1893–1898

Source: Based on trademark registration data collected from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Trademark Gazette (Tokyo, various years).

Note: Foreign trademarks are excluded in the 1897 and 1898 data. “No data” includes the trademarks that were owned by companies, not private individuals.

Table 2 Social Class of Registrants of Match Trademarks, 1893–1898

Source: Based on trademark data collected from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Trademark Gazette (Tokyo, various years).

Note: Foreign trademarks are excluded in the 1897 and 1898 data. “No data” includes the trademarks that were owned by companies, not private individuals.

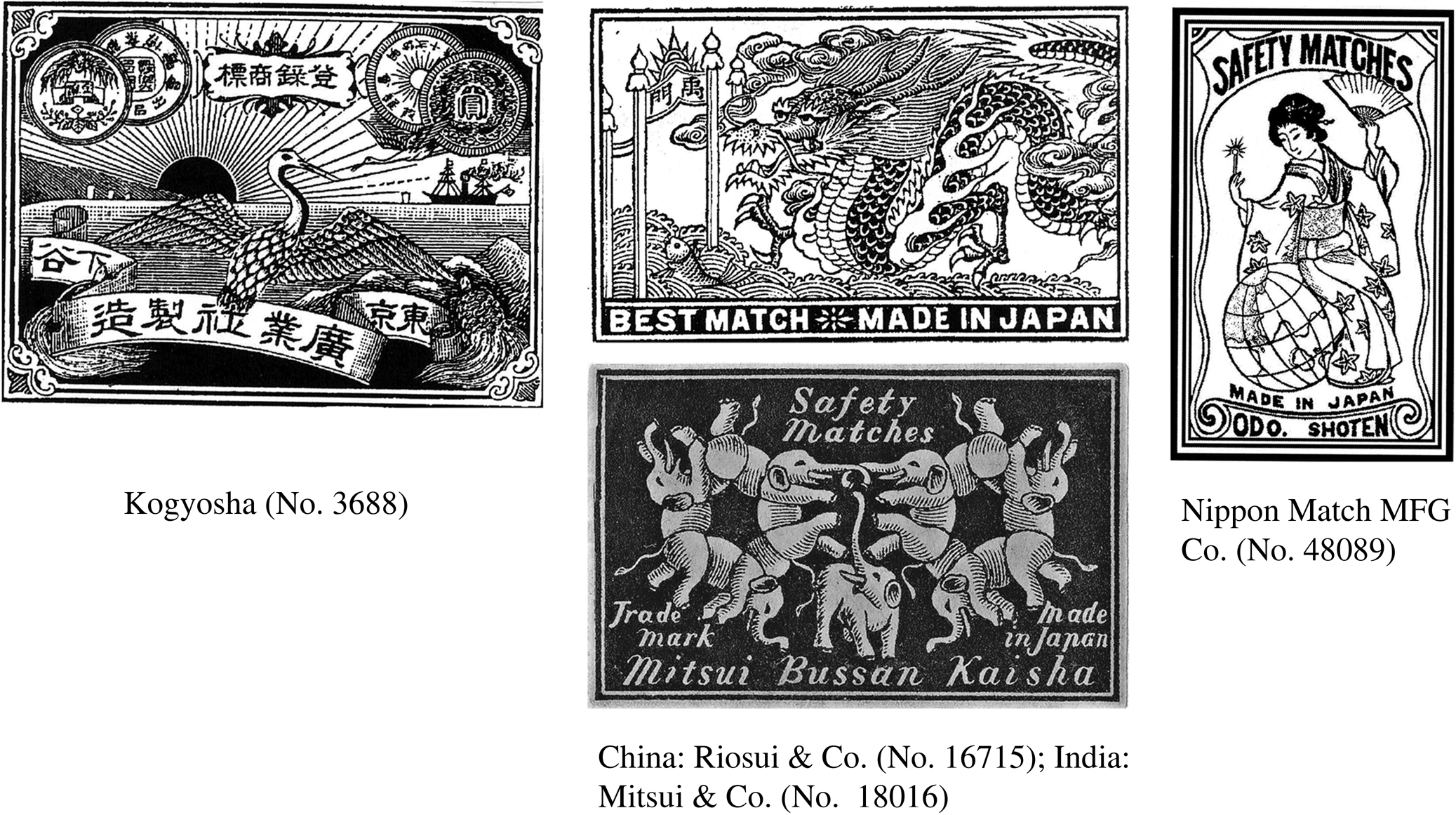

From the analysis of both tables, it is clear that the “commoners” were the main social class of registrants in Japan, in terms of both total registrations of trademarks in the country and registrations of match trademarks. The significance of the “samurai” in the registration of match trademarks is, however, higher than in relation to the total number of registrations for all classes in Japan, providing an indication of the entrepreneurial role of former samurai in the early years of development of the match industry.Footnote 76 The presence of multiple loopholes and deficiencies in the Japanese trademark registration system led to the spread of local imitations during the early development of the match industry, creating a structural fragility in the industry.Footnote 77 It was difficult for the match associations to control the behavior of the industry as a whole because there were many small and medium-sized factories in Osaka, Hyogo, Hiroshima, Okayama, Aichi, Wakayama, and Kagawa, and also because there was no uniformity and there was a lack of coordination of procedures among the different prefectures.Footnote 78 The most successful trademarks tended to attract more imitations, impacting on the business activities of the original brand owners. An illustration is the case of entrepreneur Naoki Masanosuke, who in 1891 collected twenty-six registered trademark imitations of his brand Bestmatch (No. 2894). Figure 3 provides a few examples. The original trademark is the image at the top left; the other three images are registered imitations, which use a very similar label design but different names: Sadajiro Inoue (No. 3479), Ichijiro Seto (No. 3440), and Tane Kobayashi (No. 3465).

Figure 3. Bestmatch trademark registrations: Original and imitations. The original trademark registration (No. 2894) is at top left; the other three (Nos. 3479, 3440, and 3465) are imitations. Source: Based on trademark data collected from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Trademark Gazette (Tokyo, various years).

These imitations had initially been accepted by the Patent Office for registration because, according to the law in place, they were considered to be only partial imitations. For example, as seen in Figure 3, while keeping the general appearance and design of the trademark, the imitations had a different drawing at the top left corner, including an elephant with a man, a rabbit, and a hat. Eventually, Naoki Masanosuke, the original owner, protested directly to the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in charge of the Patent Office and was able to get the Patent Office to cancel the registrations of all the imitations.Footnote 79 There are also cases of imitators of Japanese trademarks in foreign markets.Footnote 80

Innovation in commercial graphic design and printing

Japanese culture is considered to be an aesthetic culture. Part of the charm of Japanese art lies in its apparent simplicity—clean lines, rich colors, and the traditional focus on animals and birds, landscapes, flowers, meisho-e (pictures of famous places), and beautiful women. Meiji-era Kyoto nihonga artists employed craft techniques and design in a painting style that took naturalism and simplicity as founding principles and became renowned worldwide.Footnote 81 They worked in these genres as their predecessors had, but because of Japan's opening up to the world, they started recalibrating these ideals with Western artistic techniques and imagery, which were perceived as being modern. This led to a metamorphosis in fine and applied arts that was quite revolutionary.Footnote 82 Along with compositional and linear techniques seen in both painting and woodblock prints, this new style that combined different cultures helped to develop a new fad known as “Japonism.” The craze for this style is very visible in the late nineteenth-century works of European and American painters and collectors such as Degas, Monet, and especially van Gogh, whose Bridge in the Rain (1887) is a direct copy of Hiroshige's great Sudden Shower over the Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake (1857). The influence of traditional Japanese art forms also became visible in models for ceramics, lacquer, and metalwork and enjoyed special prestige.Footnote 83 As a part of opening up the Japanese economy, the government encouraged businesses to participate in international exhibitions by displaying Japanese goods. As the Japanese economy and its industries were not technologically developed, the Meiji government, in consultation with foreign advisers such as Gottfried Wagner (1831–1892), decided to invest in exhibiting products with high levels of artistic skill. International exhibitions became important events where Japanese manufacturers showcased their innovative artistic skills. The simple and naturalist designs attracted a lot of attention at these international exhibitions.Footnote 84 These events also served as venues for Japanese entrepreneurs to learn about Western art and Western estimations of artistic value.Footnote 85

Along with the modernization of Japanese art and design, a new industry of commercial graphic design developed during this period, which basically translated to the merchandising of conceptions of Japanese culture. Designs were introduced in manufactured goods, reinforcing the idea of Japan as a modern nation with unique characteristics. Commercial graphic design highlighted Japan's distinctive past as well as its adoption of modern institutions, suggesting that Japan had the strength of history but was industrializing.Footnote 86 In 1870 the first daily newspaper was printed in Japan and included advertisements. One year later, in 1871, the first stamp was issued in Japan. Acknowledging the country's strengths as well as the fads associated with Japanese art and culture in foreign markets, matchbox producers invested in new label design, packaging, and printing techniques. The artistic work on matchboxes, besides serving as an enticement for customers, provided visual expressions of Japan's national identity for foreigners and Japanese alike and were a source of national and artistic pride.Footnote 87

Matchbox labels evolved with technological advancements in commercial printing, the level of internationalization of the industry, and changes in the preferences in host markets.Footnote 88 As illustrated in Figure 4, matchbox designs in Japan were initially pure imitations of Western matchboxes by producers such as the Swedish Match Co. Gradually, matchbox labels evolved from designs that strongly relied on Japanese culture and art to designs that were essentially adaptations to host countries’ cultures and lifestyles, or were hybrids of Japanese culture and the host country culture.Footnote 89 Figure 5 shows one example of each. These adaptations increased the competitiveness of Japanese match manufacturers in host markets.

Figure 4. Imitation of the Swedish Match Co. trademark. At left is the original Swedish Match Co. trademark; at right is the Japanese imitation (Trademark No. 321) by Benzo Takigawa (Seisuisha). (Source: Yukata Kato, Matchbox Label Paradigm [Tokyo, 2011], 8.)

Figure 5. Types of trademarked designs used for the domestic market and exported Japanese matchboxes. At left is an example of a design focused on Japanese culture and art, for the domestic market. In the center are designs for export, adapted to host countries (top: China; bottom: India). At right is a design that mixes Japanese culture and art with a global approach (exported from Kobe in Japan to Honolulu, Hawaii). (Source: Japanese trademark registrations database based on Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, Trademark Gazette [Tokyo, various years].)

Label designs showed images of local daily life and expressed human emotions, customs, fashions, and other traditions and religious beliefs of the host countries. They portrayed images associated with nature (e.g., sun, moon, flowers, fruits), people (e.g., beautiful women wearing different types of costumes adapted to the host country markets), animals and creatures (e.g., elephants, birds, fish, dragons), tools and modes of transport (e.g., bicycles, ships, trains, balloons), or symbols (e.g., flags, angels).Footnote 90

Printing techniques also evolved, from woodblock and copperplate printing, which were traditional methods used in the Edo periods to print ukiyo-e, to electric copperplate printing. Lithography also started being used in the trademark printing industry. Colors of labels changed from monochrome or two-color printings to three or four colors. Prints on white paper became more frequent than on yellow paper.Footnote 91 In the early twentieth century, Japanese manufacturers and label-printing companies conducted joint research and developed sulfur-resistant red ink, so-called hosu-ink, which withstood the hot temperatures of markets such as India. As a result, the labels became very artistic, attractive, and of good quality. Additionally, a new industry developed during this period: “phillumeny,” the hobby of collecting match-related items such as matchboxes and matchbox labels. In countries such as India, Malaysia, China, and Japan, and also in Europe, there was a craze for these beautifully designed matchbox labels, leading some matchboxes to be sold in collectors’ markets at significantly escalated prices.Footnote 92 During the 1910s and 1920s a major innovation was the printing of higher-quality multicolored labels/trademarks.Footnote 93 Technological developments associated with printing machines allowed trademarks to become true works of Japanese art.

Conclusion

The global match industry provides a case of how, in the early development of an industry, it is possible to achieve international competitiveness by combining low labor costs and low prices with differentiation strategies of products that would otherwise be undifferentiated. This was achieved through the branding and the registration of trademarks, among other marketing innovations of products. Between the 1870s and the 1930s Japan became a major challenger of the world's technological leader, the Swedish Match Co., and had a great impact on global industry dynamics. While the Japanese government had a direct and central role in developing international competitiveness in the silk and cotton industries, which were the main exported goods from Japan during the period of analysis, such was not the case in the match industry. The early development of the industry relied essentially on private entrepreneurship, primarily by former samurai. Two regional clusters for match production developed, in Hyogo and Osaka Prefectures. A number of Japanese economic groups developed in this period, most notably the multinational Mitsui & Co., that was essential in the development of the domestic match industry and its international competitiveness. Mitsui & Co., apart from being the most important Japanese distributor of matches in foreign markets, not only helped to reduce the industry's prior dependency on Chinese and Indian merchants in its exports but also provided financing and logistical support for entrepreneurs to develop their own match-producing businesses.

The coordinated actions of the Japanese match producers and other stakeholders, among which Mitsui & Co. played a central role, led to the creation of private match trade associations. These associations regulated the activities of members regarding decisions about the standardization of quality and how to achieve differentiation of Japanese matches in relation to foreign competition, through trademark registrations, marketing innovation, and total quality-control practices. The trade associations promoted a utilitarian approach to art and design in matchbox labels among its members, as a way to help enhance the reputation of the industry internationally and boost trade. Designs evolved from simple imitations using one- or two-color printing, solely for the Japanese market, to multiple colors and different types of imagery largely adapted to the host markets and cultures. These local adaptations were particularly important in strategic markets like India, where Japanese match producers had to compete with the Swedish Match Co. for market share. Distribution strategies also evolved, relying more and more on Japanese economic groups and Japanese merchants and less on foreign parties. Presence at international fairs and exhibitions provided key structural and chronological frameworks for developing the dominant patterns of thinking about art and contributed to the fast growth in exports as well as to creating a reputation for matches, which became true “merchants of Japanese skill and culture”, showcasing and selling the artistic skills of the country. The growth of the match industry in Japan also spurred the development of related industries. Some of these industries operated along the value chain, such as the supply of wood from trees grown in the northern part of Japan for the production of match splints, or the graphic design of labels. Other related industries, such as phillumeny—that is, the art of collecting match-related items (e.g., matchboxes and match labels)—also emerged during this period.

The systematic use of trademarks for every single brand exported provides very useful insights about the early evolution of the Japanese match industry; in addition, it illustrates the advantages of looking beyond traditional economic indicators such as productivity, technology, and economic growth. In a period when Japan could not rely on the superior technological performance of its industries to achieve international competitiveness, the registration of multiple trademarks combined with innovative marketing strategies was crucial for the industry success and competitiveness. The use of exclusive and sophisticated designs was a way to create differentiation, in the eyes of consumers, of a product that would have been otherwise undifferentiated.

Appendix 1: Total trademark registrations for matches, silk, and cotton, 1885–1920