Introduction

Why do business leaders support or oppose interstate wars? Business pressure is often seen as a key mechanism whereby economic interdependence leads to interstate peace, yet we know surprisingly little about what business leaders think about interstate war.Footnote 1 Unlike the sprawling international political economy (IPE) and comparative political economy (CPE) literatures on businesses’ foreign economic policy preferences, there is not a large analogous body of research on businesses’ foreign security policy preferences.Footnote 2 Although scholars in the growing “businesses and peace” research agenda have investigated the role of businesses in mediating and resolving intrastate wars and civil conflict, this research doesn't explicitly theorize businesses’ foreign security policy preferences.Footnote 3

This article therefore clarifies and empirically illustrates two competing perspectives on the sources of business war preferences, the opinions businesses have about interstate conflict. First, some scholars have argued that business war preferences stem primarily from the economic consequences of conflicts. Because large interstate wars often disrupt international trade, these scholars argue that a business's war preferences stem from their trade policy preferences: businesses that support free trade will oppose wars, while businesses that oppose free trade will support war.Footnote 4 This “economic consequences” perspective, however, has yet to be empirically tested and has been criticized as temporally bounded to historical conflicts in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 5

Second, scholars studying American foreign policy opinion have long noted a correlation between policy elites’ opinions on foreign and domestic policy issues.Footnote 6 Drawing on this insight, a “leader ideology” perspective on business war preferences predicts that business leaders’ war preferences will often diverge from the economic circumstances of the business considered as a unitary actor. Instead, a business leader's domestic policy preferences and political ideology will determine their war preferences.

I test these perspectives empirically using one of the few historical surveys of business war preferences. Specifically, I reexamine historical survey data on American business leaders’ opinions about the Vietnam War using newer empirical techniques like item response theory (IRT) scaling and regression analysis that were not widely used when the survey was originally conducted in the early 1970s. I find support for both the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives. Internationalist business leaders whose businesses earn a substantial proportion of their profits from international trade are more likely to oppose the Vietnam War than domestic-oriented businesses that are engaged primarily in domestic commerce. Conversely, business leaders who take a more restrictive view of domestic civil liberties are less likely to oppose the Vietnam War than business leaders with a more expansive view of domestic civil liberties.

These results point toward the importance of further theoretical and empirical research on the sources of business war preferences. In the conclusion of this article, I therefore propose a structured, forward-looking research agenda on business war preferences. Specifically, I note how different conceptualizations of businesses and their motivations, as well as different assertions about the consequences of interstate conflicts, can lead to numerous additional theories of business war preferences. Developing and testing these theories will further sharpen insights from the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives on business war preferences.

Why, though, should we care about business war preferences? Some scholars have long been skeptical that businesses play an important role in foreign security policy. Economist Joseph Schumpeter, for instance, called the notion that businesses affected foreign policy a “fairytale, almost ludicrously at variance with facts.”Footnote 7 Similarly, realist theories of international relations have long argued that national security imperatives trump domestic economic and political interests as determinants of foreign security policy.Footnote 8

These views seem worthy of reinspection, however, given the tremendous economic disruptions that businesses face as a result of interstate conflicts.Footnote 9 Businesses care about and act to influence foreign economic policy based on its distributive consequences, so why wouldn't businesses also do the same for foreign security policy?Footnote 10 Even if foreign security policy isn't directly affected by business pressure, might political leaders still be forced to compensate businesses if these policies have negative economic consequences? Definitively answering questions about businesses’ potential effect on foreign security policy is incredibly hard absent a clear understanding of what businesses want from foreign security policy. Theories of business war preferences are therefore an important first step toward understanding the effect businesses may, or may not, have on foreign security policy.

In the sections that follow I first summarize the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives on the sources of business war preferences. Second, I lay out a research design for testing hypotheses deduced from these perspectives using historical survey data, IRT scaling, and regression analysis. Third, I describe the data I use to test my hypotheses, a rare survey of American business leaders from 1973 that captures their opinions about the Vietnam War, and report results from an IRT model that measures their domestic policy preferences. Fourth, I summarize the results from my regression analysis that tests the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives. Fifth, I discuss the implication of these results for our understanding of business war preferences. Finally, I conclude by laying out a structured, forward-looking agenda for further theoretical and empirical research on business war preferences.

Two perspectives on business war preferences

Why do business leaders support or oppose interstate wars?Footnote 11 In other words, where do business leaders’ war preferences—their opinions about interstate conflict—come from? There is a rich IPE literature on businesses’ foreign economic policy preferences but far less research on businesses’ foreign security policy preferences. Broadly, an actor's preferences refer to their rank ordering and relative affinity over potential outcomes. A business's policy preferences, then, are their rank ordering and relative affinity over policies a government might choose to enact. In turn, business war preferences are the rank ordering and relative affinity that businesses have over whether a state should initiate, join, or continue a war, or instead remain or revert to peace. They are a “preference over outcomes”—that is war or peace—rather than a “preference over strategies.”Footnote 12

Existing research on business war preferences coalesces around two distinct perspectives on the sources of these preferences.Footnote 13 First, there are scholars that treat businesses as unitary actors and explain business war preferences based on the economic consequences of conflicts.Footnote 14 I term this the “economic consequences” perspective on business war preferences. Second, recent research on business leaders’ domestic policy preferences highlights the role of a leader's broader political ideology in determining their policy preferences.Footnote 15 Analogizing these dynamics to business leaders’ war preferences yields a distinct “leader ideology” perspective on the source of these preferences.

The economic consequences perspective

The vast majority of scholars that study business war preferences argue that these preferences are primarily—if not exclusively—determined by a business's economic circumstances. Conceptualizing businesses as unitary, rational actors, a number of scholars argue that businesses will support or oppose war based on the economic consequences of interstate conflict.Footnote 16

Specifically, because interstate wars disrupt international trade, businesses will form war preferences based on their trade orientation, namely whether they engage in or support free international trade. Internationalist businesses that support free trade will oppose war. As Patrick McDonald puts it, “these foreign policy goals are driven by material interests seeking to avoid the well-known economic costs of military conflict.”Footnote 17 In contrast, domestic-oriented import-competing interests that prefer trade protectionism to free trade will be less likely to oppose wars, and indeed may have a preference for them. “The beneficiaries of protection, or firms that are not competitive in global markets, may support aggressive foreign policies or war for the economic benefits it provides to them. By slowing imports, military conflict raises the domestic price of traded goods and enables import-competing firms to expand their domestic market share.”Footnote 18 We can deduce the following hypothesis from this logic:

H1: Businesses that engage in and support free international trade will be more likely to oppose wars than businesses that don't engage in and oppose free international trade.

Despite its prominence in the literature on business war preferences, the economic consequences perspective can be criticized on a number of grounds. First, it hasn't been directly tested. Scholars primarily use this perspective to justify using a business's trade policy preferences as a proxy measure of business war preferences to test the effect of business pressure on policy outcomes.Footnote 19 There has been no systematic empirical research on interbusiness differences in war preferences based on the heterogenous effects of interstate conflict.Footnote 20 Second, given changes to the nature of war and international economic exchange, it may be that the economic consequences perspective is temporally limited to nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century conflicts. Stephen Brooks directly challenges the idea that contemporary interstate wars will seriously disrupt international trade, arguing that “war may not slow imports, especially for large states and/or states that fight limited wars” in the modern era.Footnote 21 As a result, he argues that “at least among the advanced states…there are no longer any economic actors who will be favorable toward war and who will lobby the government with this preference.”Footnote 22

Additional economic consequences

Scholars have also posited a number of additional economic consequences of interstate wars that may influence businesses’ war preferences, chief among them the potential production of defense-related goods, whether the war seeks to defend or acquire important markets, and the potential inflationary effects of wartime government spending. Unfortunately, these existing arguments remain somewhat theoretically underdeveloped and it is difficult to deduce clear hypotheses suitable for empirical testing from them.

For instance, although there is a large literature on the existence of a “military industrial complex” in the United States that is predisposed to support a bellicose foreign policy and interstate conflicts due to its ability to produce defense-related goods, this literature doesn't provide clear guidance as to which businesses form the complex and the war preferences of businesses outside the complex.Footnote 23 Namely, what about businesses that don't currently produce defense-related goods or hold government military contracts but might shift their business operations to do so during a war?Footnote 24 These businesses might not currently be part of the military industrial complex but also be unlikely to oppose interstate wars.

Similarly, inspired in part by classic analyses of imperialism by John Hobson and Vladimir Lenin, some scholars believe that businesses might support or oppose wars based on whether conflict will help them secure access to foreign markets or raw materials, and more generally protect foreign investments.Footnote 25 The problem here is specifying ex ante which businesses have an interest in foreign markets and raw materials and why conflict, as opposed to trade or government to government negotiation, will improve access and protect investments. Finally, concerns about wartime inflation figure prominently in many empirical discussions of business reactions to interstate conflict but it is unclear which businesses outside of the financial industry, and why, are differentially affected by such inflation.Footnote 26 I discuss how future research may sharpen these arguments such that they can be empirically tested in the conclusion of this article.

The leader ideology perspective

Might there be other important determinants of business war preferences besides a business's economic circumstances? Recent research on the American technology sector suggests that a business leader's political ideology, their foundational political predispositions and beliefs, helps to shape their domestic policy preferences.Footnote 27 Given that an individual's domestic policy preferences often correlate with their foreign policy preferences, it makes sense that a business leader's political ideology may also partially determine their war preferences.Footnote 28

This “leader ideology” perspective on business war preferences differs in important ways from the economic circumstances perspective described in the preceding text. First, it conceptualizes business leaders—high-ranking employees responsible for shaping a business's strategy—as distinct actors from the businesses for which they work. This analytical move builds off a long research tradition in the study of strategic management, dating back at least to the early-twentieth-century research of Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means, which argues businesses cannot be treated as unitary actors due to the differing preferences of owners and managers.Footnote 29

Second, this perspective introduces the idea that ideational or other nonmaterial variables might also affect a business leader's policy preferences, and subsequent actions, above and beyond their material circumstances. Here again, there is a large body of strategic management literature that explains business and organizational behavior based on the beliefs and characteristics of individual business leaders.Footnote 30 A parallel literature in international relations argues that biographical characteristics, policy ideas, and other beliefs can play an important role in determining political leaders’ policy preferences and behavior.Footnote 31 Although existing scholarship admittedly undertheorizes the precise linkages between various political ideologies, domestic policy preferences, and foreign security policy preferences, we can nevertheless deduce the following hypothesis from the leader ideology perspective:

H2: A business leader's domestic policy preferences will be a statistically significant predictor of their war preferences.

Research design

There are two main requirements for empirically testing these competing hypotheses. First, we need a method to assess potential differences in war preferences between various business leaders. Second, we need to measure a business leader's domestic policy preferences/political ideology in a comprehensive manner. I utilize regression analysis and IRT scaling to fulfil these two requirements.

Specifically, I utilize a simple model specification to test the preceding hypotheses regarding the source of business war preferences. Namely, I predict business leader i's opposition to war (Yi) as a function of whether they lead an internationalist business (Xinternationalist(i)), their domestic policy preferences/ideology (Xdomesticpolicy(i)), and their racial policy preferences/ideology (Xracialpolicy(i)), and I assess the direction and statistical significance of the coefficients for international trade (β1), political ideology (β2), and racial ideology (β3). The specification also includes a vector of additional control variables and their associated coefficients (γ(i)), and intercept (β0) and stochastic error (ɛi) terms. The preceding hypotheses align to this model specification in the following way. H1 implies that β1 should be positive and statistically significant while H2 implies simply that β2 and β3 should be statistically significant.

I include two separate variables to measure respondents’ political ideology to measure their ideology along two key dimensions: specific views on racial politics and more general views on domestic rights and liberties. Since the work of Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal, many scholars of American politics have argued that racial politics, civil rights, and social welfare issues occupy a separate dimension from other ideological concerns.Footnote 32 Generally speaking, however, the relevant dimensions of business leaders’ political ideology will be context specific, and may depend on both geographical and temporal factors.Footnote 33 Scholars should therefore think critically about how many variables they will need to include in a model specification to test the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives on business war preferences given the relevant, case-specific dimensions of business leaders’ political ideology in the context they are studying.

How, then, should we comprehensively measure a business leader's domestic and racial policy preferences? One approach would be to measure business leaders’ preferences regarding a number of individual policies and including these as a vector of individual responses. Although certainly justifiable, this measurement approach aligns somewhat poorly to the predictions of H2, which focuses on a business leader's holistic, rather than individual, policy preferences.

Viewed in this light, a business leader's domestic and racial policy preferences or ideology are latent continuous variables that can be more accurately measured based on the correlated responses to multiple individual policies rather than considering these policy responses individually.

Political scientists increasingly use IRT scaling to measure these sorts of latent concepts across a number of issue areas, including the political orientation of states,Footnote 34 the strength of peace agreements,Footnote 35 and populism,Footnote 36 amongst many other areas. I discuss in the following section how I use a graded response IRT model to holistically measure both a business leader's domestic and racial policy preferences with the survey data I use to estimate my model specifications.

Data and IRT model

There are unfortunately few historical surveys of business leaders’ war preferences. While we might also want to test hypotheses regarding business war preferences in contemporary circumstances, representative cross-industry survey samples of business leaders are incredibly difficult to assemble.Footnote 37 Utilizing historical survey data can also help set a baseline expectation for variation in business war preferences that can help guide contemporary survey development.

One of the only historical surveys of business war preferences was conducted by Bruce Russett and Elizabeth Hanson of Yale University as American involvement in the Vietnam War was winding down in the spring of 1973.Footnote 38 Beyond just a convenient survey, however, the Russett and Hanson data provides evidence on business war preferences in an important historical case. The Vietnam War had underappreciated yet crucial economic effects, not just on American businesses but also on the long-term trajectory of American economic growth and the structure of the international monetary system. In particular, heightened American defense spending due to the Vietnam War was a key factor that caused the United States to suspend the convertibility of US dollars into gold in 1971, destroying the international monetary system based on the “gold-exchange standard” that had existed since the Bretton Woods conference.Footnote 39 The resulting currency crisis laid the foundation for the “stagflation” era of high unemployment, high inflation, and low economic growth in the United States throughout the 1970s.Footnote 40 The Vietnam War also offers a “tough case” for testing perspectives on business war preferences given its overall unpopularity amongst the American public.

The Russett and Hanson survey comprised a series of questions about business leaders’ foreign and domestic policy views and was mailed to a random sample of vice presidents at Fortune 500 corporations and leading firms in the financial industry (n = 1059). Russett and Hanson received 567 completed survey responses, for a response rate of 54%. Although they went to great lengths to anonymize the survey respondents, Russett and Hanson did include questions asking whether the respondent's business currently conducted or planned on conducting substantial international business. This helps with distinguishing respondents based on the trade orientation of their businesses even though they cannot be linked to individual firms or industries.

Importantly, although Russett and Hanson analyzed the foreign policy views of the business leaders in their sample, they didn't test specific hypotheses on the relationship between business leaders’ domestic policy preferences, trade orientation, and war preferences. The closest that they come is analyzing the bivariate correlation between respondents’ views on individual domestic policies and various foreign policy opinions. Here, however, they average together the correlation coefficients between an individual domestic policy and three separate foreign policy opinions: on the level of US defense spending, the effect of cuts in defense spending on US security, and the Vietnam War.Footnote 41 This approach not only makes it impossible to analyze a respondent's war preferences separately from their military spending preferences but it also doesn't control for other demographic factors or domestic policy preferences that might partially determine a respondent's war preferences.

Russett and Hanson also conducted a number of regression analyses that predict respondents’ foreign policy views based on a mixture of domestic policy opinions and measures of political ideology.Footnote 42 There are issues with this approach, however, that also make it inappropriate for testing the hypotheses I propose. First, it is unclear what model specifications Russett and Hanson estimated. They note that they introduced variables “into the regression equations with foreign policy preference as the dependent variables in each instance, using the technique of stepwise multiple regression,” but do not provide a list of which independent variables were introduced and in what order. Second, they only report the regression coefficients and standard errors for independent variables that “made a statistically significant contribution to explaining a particular dependent variable.”Footnote 43 It is impossible to conduct credible hypothesis tests without an understanding of what other variables are in these empirical models.

Measuring key variables

As a measure of war preferences, I use a respondent's answer to the question of whether they “personally think it was correct for the United States to send ground combat troops to Vietnam.” I code a respondent as opposing the war (coded as 1) if they answer “no” and as supporting the war (coded as 0) if they answer “yes.” For these initial models I drop all respondents that answer, “don't know,” but as I demonstrate in the supplementary appendix my findings are robust to coding these individuals as either opposing or not opposing the war.

As a measure of trade orientation, I code a respondent as being in an internationalist industry (coded as 1) if foreign business, excluding Canada, accounted for more than 25% of the respondent's firm's sales (or assets, if more appropriate). Otherwise, I coded them as being in a domestic-oriented business (coded as 0). In the appendix, I note that my results are robust to an ordinal measure of trade orientation that differentiates between firms where foreign business accounts for more than 25%, between 10% and 25%, and less than 10% of sales or assets. I include all possible control variables captured in the survey, including a respondent's age (a categorical variable with five categories), whether the respondent served in the armed forces (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0), and whether the respondent saw wartime service (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0). Table 1 reports descriptive statistics on these variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on survey sample

Estimating the IRT model

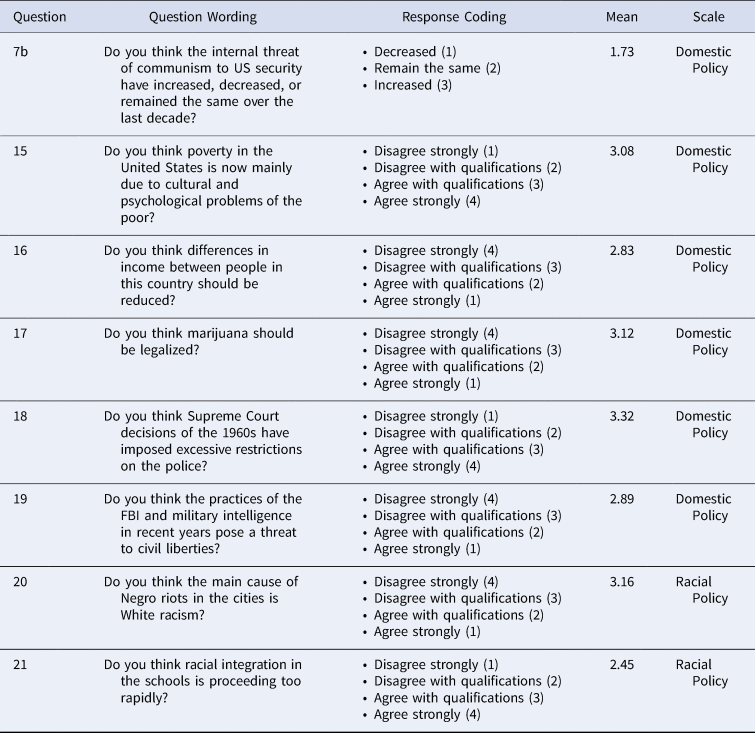

To test H2 I first construct scaled measures of a respondent's domestic and racial policy preferences using IRT models. I constructed these scales using responses from eight survey questions that asked respondents about their domestic policy preferences regarding civil rights and liberties, for instance their views on the legalization of marijuana, beliefs about communism, and support for police. An IRT model is an appropriate method for scaling these survey responses because it allows me to construct composite measures of domestic and racial policy preferences that account for the varying proportions of respondents that agree/disagree with various policy positions.Footnote 44 I used exploratory factor analysis to confirm that the responses to these survey questions load onto two distinct dimensions and present the results of this analysis in the appendix.

I utilize an IRT model as opposed to a simple summated rating scale because summated rating scales implicitly assume that responses to scale items are independent from each other and should be weighted equally.Footnote 45 Neither of these assumptions seems justified when measuring political ideology. Not only will some scale items better correspond to a respondent's political ideology than others, implying different weights, but responses will also likely correlate across different types of items. An IRT model, in contrast to a summated rating scale, calculates a business leader's ideology as a weighted average that accounts for variation between respondents and between individual questions. The question wordings and potential responses are reported in table 2, alongside whether the questions were used to construct a generic domestic policy or racial policy scale.

Table 2. Domestic policy preferences scale items

I constructed my scaled measure of domestic policy preferences by fitting a graded response model (GRM) to these survey responses. I used a GRM as opposed to other types of IRT models because these survey questions are ordinal responses rather than dichotomous responses.Footnote 46 I then used the fitted model to generate factor scores that align to each unique pattern of responses for the six questions in my domestic policy scale and two questions in my racial policy scale. These factor scores represent the domestic policy preferences of an ideal type of respondent with a particular pattern of responses. I then included survey respondents’ factor scores as an additional predictor in my regression analysis. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of factor scores from the IRT models. The results of Kendall and Spearman tests indicate that the IRT models fits the underlying survey response data well. I present the results of these tests, as well as individual Item Response Category Characteristic Curves (IRCCCs), in the supplementary data appendix.

Figure 1. Distribution of domestic policy and racial policy scores

Results

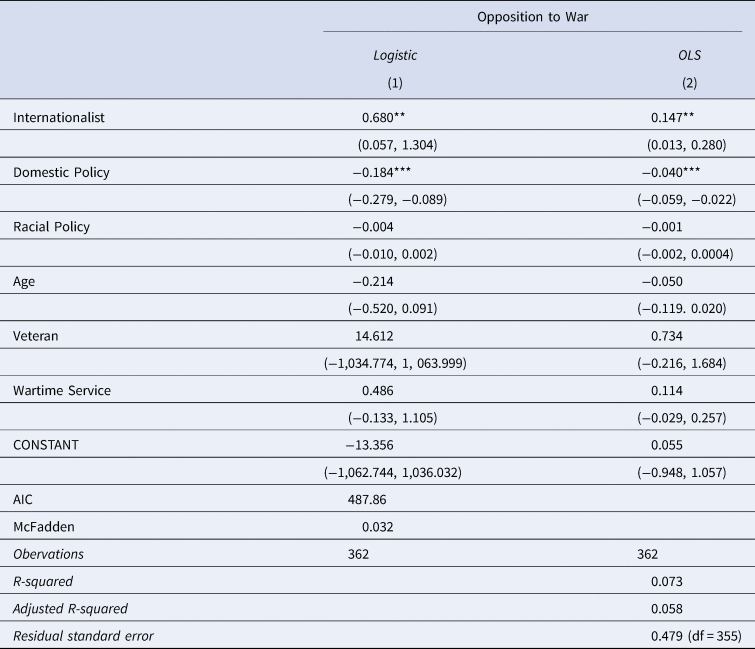

I present the results from my regression analysis in table 3. I estimated my model specifications using both Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), which implies a linear probability model, and logistic regression.Footnote 47 I interpret the substantive results of the models using the OLS model and present the marginal effects of the logistic regression model in the appendix. The positive and statistically significant coefficient (p < .05) for trade orientation (β 1) provides strong evidence for H1. Respondents with an internationalist trade orientation are 14.7% more likely to oppose the war than respondents in a domestic-oriented industry. The coefficient on my scaled measure of domestic political ideology (β 2) is negative and statistically significant, indicating that respondents who scored higher on the scale—that is had a more restrictive view of civil liberties—are less likely to oppose the war than respondents that had a less restrictive view of civil liberties. These results therefore also provide strong evidence for H2. Business leaders with a one standard deviation more restrictive view of domestic civil rights and liberties were 10.7% less likely to oppose the Vietnam War. The theoretical basis of this association, however, requires further research. The coefficient on my scaled measure of domestic racial ideology (β 3) is not statistically significant.

Table 3. Results

Notes: ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1

I report the results of a number of robustness checks in the appendix. First, there may be potential concerns that some of the questions used to construct my domestic policy scale, particularly those that ask about domestic communism and the domestic activities of the FBI and military intelligence, primarily capture respondents’ foreign policy attitudes. If true, this would obscure the potential relationship between business leaders’ domestic policy views and support/opposition to war. I therefore construct a new domestic policy scale with those questions removed and substitute it into my regression analysis. I find substantively similar results to those reported in table 3.

Second, there may be potential concerns about the endogeneity of a business leader's political ideology to a business’s economic circumstances if, for instance, internationalist businesses select different types of leaders than domestic-oriented businesses. I therefore reestimate the model results in table 3 without including a business leader's domestic political ideology. I find substantively similar results to those reported in table 3.

Finally, I conduct additional robustness checks by estimating models without control variables, alternate coding of the dependent variable that includes participants who respond “don't know” as opposing and not opposing the war, dropping respondents with outlier domestic policy preferences, and alternate coding of my independent variables including a three part ordinal-measure of trade orientation, a summated rating scale of domestic policy preferences, and the survey responses from individual scale items. The results of these robustness checks are either substantively similar or consistent with the results presented in table 3.

Discussion

The empirical results of this article provide both important contextual evidence about American business leaders’ support and opposition to the Vietnam War and also have broader significance for understanding business war preferences. First, they indicate that a business's economic circumstances, namely their trade orientation, likely remain an important factor for determining their business war preferences in modern interstate conflicts. Second, they demonstrate that business leaders’ war preferences are not wholly separate from the preferences of the business itself.

Still, it is important not to overinterpret the findings given the lack of evidence from either the survey or historiography of the Vietnam War that the key mechanism underpinning the economic consequences perspective—disrupted wartime trade—was operative during the Vietnam War. This raises the possibility that the association observed in this article between American business leaders’ trade orientation and opposition to the Vietnam War is being driven by an alternate mechanism than that specified by the economic consequences perspective.

Relevance of results for understanding business war preferences

The most important aspect of these findings for our understanding of business war preferences is the fact that a business's trade orientation still appears to be an important determinant of a business leader's war preferences in modern conflicts. The positive, statistically coefficient for increasing trade orientation across the regression results cuts against existing theoretical critiques of the economic consequences perspective that hold few businesses will support, or not oppose, modern conflicts based on their trade orientation.Footnote 48 At the same time, however, it is important not to overclaim on the basis of these results. Not only do these model specifications lack a credible causal identification strategy but these results also provide no evidence for the hypothesized mechanism linking trade orientation and opposition to war: the prospect of disrupted international trade.Footnote 49

These results also demonstrate that, although the characteristics of individual business leaders certainly matter for predicting their war preferences, the economic situation of their business also remains important. Ever since the early-twentieth-century research of Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means on the differing preferences of owners and managers, management scholars have pushed back against the notion that businesses can be treated as unitary actors.Footnote 50 As a result, however, boards of directors and owners have worked incredibly hard to minimize the gap between business leaders’ preferences and that of the organization, primarily through the structure of leader compensation.Footnote 51 Based on the evidence presented in the preceding text, as well as these theoretical insights, it would seem that treating businesses as unitary actors will yield an acceptable, if necessarily imperfect, understanding of business war preferences. The theoretical and empirical divergence between a business's war preferences and business leader's war preferences, though, nevertheless seems like a potentially important area for future research. In the following section I demonstrate how conceptualizing a business as a unitary or disaggregated actor can serve as a key starting point for a structured, forward-looking research agenda on business war preferences.

Relevance of the results for understanding opposition to the Vietnam War

The findings in this article also provide contextual evidence about American business leaders’ support and opposition to the Vietnam War, although it is important to not overinterpret the findings. Namely, given that Vietnam wasn't a large trading partner with the United States prior to the war breaking out, it isn't clear that the association between business leaders’ trade orientation and war preferences observed in the Russett and Hanson data is being driven by the mechanism of disrupted war time trade that the economic consequences perspective posits.

That is not to say that the observed association between business leaders’ trade orientation and war preferences is spurious, but rather that it may be operating through a different mechanism. It could be, for instance, that the fighting in Vietnam disrupted trade between the United States and third-party countries due to the ripple effects of the Vietnam War throughout Southeast Asian economies.Footnote 52 Alternatively, it could be that the growing, widespread international disapproval of American activities in Vietnam led internationalist American firms to pay a reputational penalty when dealing with international suppliers.

Most likely, however, the internationalist firms in the Russett and Hanson data disapproved of the Vietnam War because of the inflationary disruptions caused by the conflict. President Lyndon Johnson's refusal to finance the war through taxes versus issuing debt meant that inflation during the Vietnam War was far greater than in previous Cold War conflicts, such as in Korea.Footnote 53 Inflation was also a proximate effect of domestic supply chains bottlenecked by government demand for conflict relevant goods. For internationalist firms, inflation meant that American manufactured goods for export were now less competitive than those produced by foreign firms.Footnote 54

Unfortunately, the Russett and Hanson data does not contain enough detail to distinguish between these various competing mechanisms whereby internationalist firms in the United States might be motivated to oppose the war. Future research, however, can both productively examine these inflationary dynamics in the case of American business leaders during the Vietnam War and also, as the following section proposes, form part of a general research agenda on the economic and noneconomic determinants of business war preferences.

An agenda for further research on business war preferences

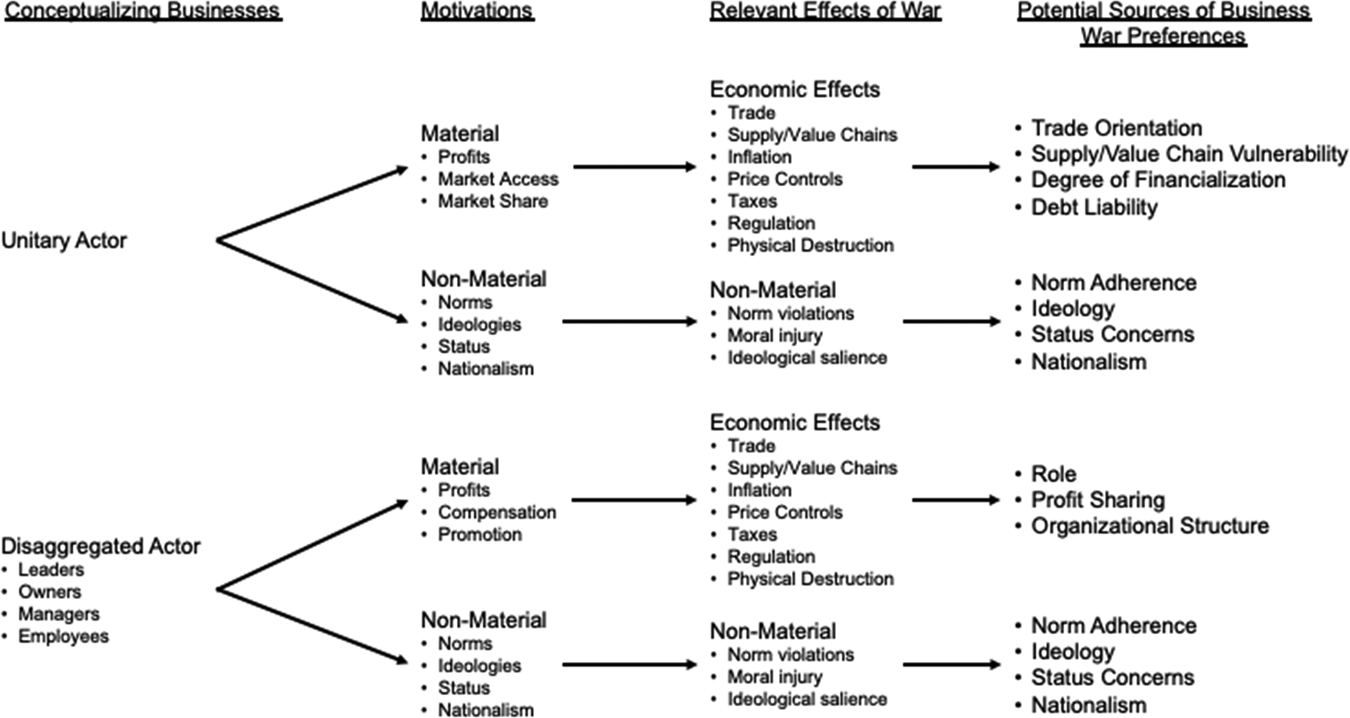

This article has clarified and empirically illustrated two competing perspectives on the sources of business war preferences: the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives. These two perspectives, however, certainly aren't the only possible theoretical perspectives on the sources of business war preferences. In this concluding section I therefore lay out a structured, forward-looking research agenda for further theoretical and empirical research on business war preferences. This agenda starts from two key conceptual differences between the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives: first, whether businesses are conceptualized as a unitary versus disaggregated actor, and second whether businesses are seen as primarily motivated by material or nonmaterial factors.

These sorts of ontological assumptions about how to conceptualize actors and their motivations are an important step in parsimonious theory creation.Footnote 55 Importantly, however, they are neither “true” nor “false.” Rather, different ontological assumptions will simply lead to different theories of business war preferences by highlighting different consequences or relevant effects of interstate conflicts, and different sources, or independent variables, that might determine business war preferences. The research agenda that I propose, as visualized in figure 2, represents just one potential way to think about further research on the causes of business preferences. Like all such metatheoretical taxonomies, it also inevitably minimizes or ignores potentially fruitful areas of research on business war preferences because of its own inherent ontological assumptions. By clarifying these assumptions, and their theoretical implications, however, this research agenda can serve as an important touch point for future research on business war preferences through either its implementation or criticism.

Figure 2. A research agenda on business war preferences

The first key ontological question facing further theoretical research on business war preferences, as visualized by the leftmost column of figure 2, is whether businesses should be conceptualized as unitary actors, as in the economic consequences perspective, or disaggregated into multiple sets of actors. The leader ideology perspective highlights how one type of disaggregated actors, business leaders, might hold different war preferences than the business as a whole. There are a number of other types of disaggregated actors, however, such as business owners, managers, and employees, whose war preferences might vary in important ways vis-à-vis each other and the business as a whole.Footnote 56

Second, as represented in the second column of figure 2 there is the question of what motivates businesses. Specifically, are businesses and disaggregated actors motivated by material concerns like profits, market access, market share, or compensation? Or are they motivated by nonmaterial concerns like norms, ideologies, status, or nationalism? Third, as the third column of figure 2 demonstrates, these ontological microfoundations point toward different relevant consequences/effects of interstate conflicts. Economic consequences of conflict such as disrupted international trade, disrupted supply or value chains, inflation, taxes, and so on will be relevant to businesses motivated by material concerns. Businesses or disaggregated actors motivated by nonmaterial concerns, though, will be more interested in how wars might violate norms or increase the salience of certain ideologies.

Finally, the right-most column of figure 2 links these different consequences/effects of wars to specific sources of business war preferences. In turn, these sources can be seen as key independent variables that theoretically cause variation in business war preferences. Because the consequences of wars will inevitably fall heterogeneously across different types of businesses, we can deduce testable hypotheses about which business will support/oppose war based on different types of businesses and actors and how they are affected by interstate conflicts.

For instance, the empirical finding presented in this article—that there is a statistically significant relationship between a business leader's domestic policy preferences and war preferences—begs for a stronger theoretical explanation than the leader ideology perspective currently provides. In addition to theorizing the relationship between a business leader's preferences about the restriction of civil liberties and their war preferences, however, there may be other domestic policy preferences that may be theoretically related to war preferences, such as a business leader's preferences regarding government spending in general or role in regulatory policy. These latter domestic policy preferences will likely only be important for a business leader's war preferences if we conceptualize business leaders as motivated by both material and nonmaterial concerns.

There may also be other demographic or ideational determinants of business leaders besides domestic policy preferences that matter for determining their war preferences. Any number of factors, including a business leader's strategic rationality,Footnote 57 overconfidence,Footnote 58 past life experiences,Footnote 59 family situation,Footnote 60 and thrill-seeking behavior,Footnote 61 amongst others, might credibly be related to a business leader's war preferences. Alternatively, looking beyond a single leader and to the advisors around them, it might be that the collective experiences and beliefs of business leaders matter for a business's war preferences above and beyond any individual characteristics.Footnote 62

The proposed research agenda in figure 2 may also be expanded on in three distinct areas. First, basing this research agenda on agent-centered ontological assumptions invariably minimizes the role environmental factors might play in determining business war preferences. Structural factors, such as the normative environment, economic system, or domestic regime type in which businesses operate might also be distinct causes of business war preferences or mediate the relationship between a businesses’ individual characteristics and their war preferences.Footnote 63

Second, a growing literature on the “political economy of security” highlights how the economic consequences of wars are endogenous, political outcomes rather than being exogenous.Footnote 64 A better understanding of the strategic interaction between businesses and governments in setting wartime tax, regulatory, and trade policy will further sharpen an understanding of both the sources of business war preferences and how businesses acting based on those preferences affect wartime economic policy. Third, although this article has focused exclusively on businesses’ preferences regarding interstate wars, future theoretical research should also investigate businesses’ preferences regarding intrastate and civil wars. Despite a growing literature on “businesses and peace,” this research has yet to seriously investigate businesses’ civil war or civil conflict preferences.Footnote 65

Finally, additional empirical research on business war preferences should further test both the economic consequences and leader ideology perspectives on business war preferences, as well as additional and potentially more rigorous hypotheses, across a range of spatial and temporal contexts using a variety of research methods. Particularly if business war preferences may be affected by structural variables such as differing economic systems or domestic regime types, it is important to test theories of business war preferences in a number of differing regional and country contexts. Moreover, given existing theoretical critiques regarding potential temporal scope conditions on theories of business war preferences, alongside the shifting nature of warfare and the international economy, it is important to test theories of business war preferences across a variety of temporal contexts.Footnote 66 If the enduring and expanding scholarly literature on businesses’ foreign economic policy preferences are any guide, there will be fruitful avenues for both empirical and theoretical research on business war preferences for years, if not decades, to come.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2021.22.