“I was in the world of business for 25 years. If you didn't balance your budget, you went out of business.”

—Mitt Romney, 2011, presidential debate.Footnote 1Thus spoke then presidential candidate Mitt Romney during a CNN debate with President Barack Obama in 2012. Later in the same debate, Romney clarified his vision by stressing the importance of cutting government spending (with the notable exception of defense spending) without increasing taxes. Earlier that year, the Republican candidate even floated the idea that future presidential candidates should be required to have spent “at least three years working in business before [they] could become president of the United States.”Footnote 2 The tendency for former businesspeople to emphasize their private sector credentials is not limited to the US case. The touting of business experience is often a hallmark of political campaigns around the world, such as in Italy,Footnote 3 Bahrain,Footnote 4 Thailand,Footnote 5 and Egypt.Footnote 6

Whether prior business experience in economic policymaking is a valuable asset is still an open question.Footnote 7 In this study, I propose and test some expectations relating political leaders’ business experience to fiscal consolidation preferences.Footnote 8 This article extends the literature on the political economy of fiscal policies and the literature on individual leaders’ characteristics in several ways. Conceptually, I build on previous studies in sociology, psychology, political science, and business studies to suggest why and how one specific occupational experience—that of former businesspeople—is linked to fiscal policy preferences. Methodologically, I complement previous studies on the effects of leaders on public debt with a research design that accounts for business politicians’ self-selection into office. First, I take advantage of recent developments in macroeconomic research and utilize a dataset on fiscal consolidations that are weakly exogenous to the business cycle.Footnote 9 By doing so, the empirical analysis partly accounts for the primary endogeneity concern that has affected previous studies—that is, the selection of former businesspeople into politics as a function of the economic cycle. Second, I further probe the causal nature of the relationship by analyzing a subset of as-if random elections. Finally, I complement the statistical analysis with an illustrative case study of Brian Mulroney's governments in Canada (1984–93). In a nutshell, I uncover two main findings. First, politicians with prior business experience are more likely to pursue fiscal consolidation for the purpose of restoring a balanced budget. Second, they tend to implement fiscal consolidation policies based on spending cuts rather than tax increases.

The article is organized as follows: In the first section, I review the literature on the effect of individual leader characteristics on public policy, with a particular emphasis on fiscal policy. Then, I draw from an interdisciplinary literature on the individual traits of businesspeople to derive a set of testable implications. The third section describes the research design. First, I introduce the dataset on weakly exogenous fiscal adjustments and explain how and why it helps us overcome some of the methodological challenges faced in previous studies. Next, I describe the coding of business experience and the modeling strategy. The following section contains the main empirical results. Then, I illustrate and deal with the most pressing endogeneity concerns. The penultimate section presents a qualitative case study, and the conclusion follows. The online appendix describes several checks of the underlying assumptions and further probes the robustness of the results.

Individual traits and public policy

“In the real world, individuals, as such, do not seem to make fiscal choices. They seem limited to choosing ‘leaders,’ who will, in turn, make fiscal decisions.”

—James BuchananFootnote 10Why should individual-level characteristics matter for policy outcomes? After all, according to standard Downsian models, individual-level traits should not matter at all. Candidates respond to the median voter's preferences in order to maximize their chances of remaining in power.Footnote 11 If this is the case, policy outcomes should be independent of leaders’ characteristics.Footnote 12 Indeed, this is the implicit premise underlying most political economy explanations of fiscal consolidation. By emphasizing the role of economic and political conditionsFootnote 13 and/or domestic institutions,Footnote 14 leaders are implicitly modeled as having no independent stance toward fiscal consolidation, but only a (strong) preference for those economic policies that would solidify their political power. Nevertheless, alternative models are not so restrictive. By relaxing the assumption that politicians are simply driven by vote-maximization and/or office-seeking goals, these models allow for the possibility that policymakers would enact their personally preferred policies. For instance, in “citizen-candidate” models, candidates cannot credibly commit to enact policies that are inconsistent with their own personal preferences.Footnote 15 Thus, under these models, a leader's traits matter in determining their preferences.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, fiscal policy preferences at the executive level have rarely been explained, with the partial exception of ideology.Footnote 17

Recognizing the potential role of individuals, a growing empirical literature has been connecting leaders’ personal traits to the public policies they enact once in office.Footnote 18 These studies tend to emphasize leaders’ socializing experiences, such as education and occupation.Footnote 19 Within the broader literature on leaders’ biographical characteristics, we can situate a narrower set of studies focusing on fiscal policy and public debt. Dreher et al. were among the first to study the effect of leaders’ occupational and educational backgrounds and to find some evidence that former entrepreneurs are more likely to undertake liberalizing reforms.Footnote 20 Similarly, Mikosch and Somogyi explore the variation in public deficits across countries as a function of leaders’ occupational and educational background.Footnote 21 At the subnational level, Beach and Jones zoom in on city councils in California to investigate the public policy effects of business politicians.Footnote 22 Leveraging close elections in a regression discontinuity framework, they find no evidence that the election of a business candidate has an impact on city expenditures or revenues. Using a similar research design, Kirkland finds that mayors with business background shift the allocation of expenditures by curtailing spending for redistributive policies.Footnote 23 In the German context, Jochimsen and Thomasius investigate how several characteristics of regional finance ministers affect the Laenders’ public deficits, but they find no effect of leaders’ (nonfinance) business sector experience.Footnote 24 By contrast, Szakonyi uncovers more pernicious effects in the case of Russian subnational governments.Footnote 25 The author shows that former businesspeople prioritize policies that would bring immediate benefits to private firms rather than the general public, succinctly concluding that these actors run the local government ”for business” rather than ”like a business.” Finally, Hayo and Neumeier find that leaders with higher socioeconomic status exhibits more fiscal discipline.Footnote 26

The aforementioned studies contribute to our understanding of how individual leaders matter even in fiscal policy. Nevertheless, they also highlight a number of potential challenges in studying the relationship between individual traits and public policies. First, some of the previous studies did not dig into the specific theoretical mechanisms linking professional experience to policy outcomes.Footnote 27 For example, while both Dreher et al.Footnote 28 and Mikosch and SomogyiFootnote 29 argue that policymakers’ distinct preferences may lie in professional (or educational) socialization, they do not theoretically elaborate on which backgrounds might be more relevant and the specific mechanisms linking individual backgrounds to fiscal preferences. Second, as several authors have noted, endogeneity concerns loom large in individual-level studies.Footnote 30 Most importantly, the selection mechanism leading businesspeople into political office is confounded by a host of factors that may also impact a countries’ fiscal policy. To be sure, some scholars have carefully adopted research designs that account for leaders’ selection into political office, often leveraging close elections in a regression discontinuity framework.Footnote 31 Nevertheless, the literature on individual-level traits at the national level has often ignored the selection mechanism.

These methodological challenges, in turn, might partly account for the presence of null or even counterintuitive results in the literature. For example, in the previously cited study by Mikosch and Somogyi,Footnote 32 some of the findings even contradict the authors’ hypothesis that individuals with an economics degree or experience in business should correlate with a reduction in national public debt. Likewise, Jochimsen and Thomasius's work finds that leaders with business experience in nonfinance sectors are associated with higher deficit levels.Footnote 33 At the same time, Hayo and Neumeier show that upper-class leaders are generally associated with lower deficit-to-GDP ratio.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, once they disaggregate the analysis by specific professions, businesspeople are not found to be more deficit averse.

Business experience and fiscal consolidation

Why should a former businessperson have systematically different fiscal policy preferences relative to their nonbusiness counterpart? I highlight three main channels through which businesspeople may have systematically different fiscal policy preferences. First, socialization effects from working in the business sector will positively affect the individual's beliefs regarding the benefits of a balanced budget in general and expenditure-based (as opposed to tax-based) fiscal consolidation in particular; second, shared material interests with their previous professional network are likely to predispose these leaders to favor the type of fiscal consolidation that is least likely to damage business interests—that is, expenditure-based (EB) fiscal consolidation; third, former businesspeople are likely to exhibit a distinct perception of their own (perceived) ability to sustain the fiscal consolidation process as well as its electoral consequences. While it is not possible to disentangle these mechanisms at the country level, they do provide a useful analytical framework for the study of individual leaders’ characteristics.Footnote 35

Socialization

A vast body of research in social psychology has shown how individual beliefs spread through intergroup and interpersonal relations.Footnote 36 It has long been observed that the workplace affects one's attitudes and behaviors even after accounting for self-selection, a phenomenon known as “workplace socialization” in sociology.Footnote 37 Such formative experiences are unlikely to be forgotten once an individual enters politics.Footnote 38 In addition to the factual knowledge acquired in the workplace, any (nontrivial) occupational experience implies the internalization of the fundamental values that occupation is based on.Footnote 39 These beliefs come to constitute individuals’ cultural imprints and worldviews and, either consciously or unconsciously, inform their preferences once in a position of (political) power. In other words, occupational experiences serve as a template for understanding and acting in the social world; experiencing a similar set of incentives, conditions, and ideational exposure will have an homogenizing effect on preferences within the same (occupational) class.Footnote 40 In particular, working at a firm is likely to heighten an individual's perception regarding the benefits of avoiding persistent structural deficits. Indeed, excessive government spending can be seen as a symptom of bad political management and lack of coherent leadership.Footnote 41 As running a deficit is the public sector equivalent of a company taking a loss, fiscal responsibility is likely to become a key element of an administration led by a former businessperson. As Romney's quote in the introduction nicely summarizes it, the rule in the private sector is quite simple: if you don't balance your budget, you go out of business.

To be sure, taking on a reasonable amount of debt is a precious financing tool for firms (as well as governments), but businesses are generally more sensitive to the demands of their shareholders who require sustainable profits and to shy away from uncertain investments.Footnote 42 While former president Donald Trump has often boasted being the “king of debt,” running long-term unsustainable deficits is hardly a winning strategy for a typical firm. Indeed, the finance literature offers two main models of firms’ financing decisions and its relationship with a firm's profitability: the trade-off and the pecking-order model.Footnote 43 Conventionally, the trade-off theory of capital structure has been interpreted to suggest a positive relationship between firms’ profitability and the leverage ratio—that is, the amount of debt relative to equity. If that were the case, it would be hard to suggest that business experience socializes individuals to value budget balancing. If anything, business leaders may be tempted to opt for a more aggressive debt financing strategy in line with their prior knowledge on how to run a successful company. Nevertheless, the trade-off theory's prediction regarding the profitability-debt financing relationship runs counter to the established empirical fact that more profitable firms actually have a lower leverage ratio (less debt).Footnote 44 Indeed, a negative relationship between firms profitability and leverage ratio has been found in starkly different contexts, such as several European countries in a comparative perspectiveFootnote 45 as well as in single-country studies.Footnote 46 According to financial economist Stewart Myers, “the strong inverse correlation between profitability and financial leverage” constitutes “the most telling evidence against the static trade-off theory.”Footnote 47 In an attempt to solve the “capital structure puzzle,” Myers and others developed an alternative theory known as the pecking-order model of financing decisions. While a comprehensive description of this alternative model is beyond the scope of this article, it should suffice to say that it establishes a negative relationship between profitability and leverage ratio. The key aspect is the introduction of future-oriented concerns from profitable firms, which refrain from incurring excessive debt in the present to avoid forgoing future investments and/or having to finance them at a higher borrowing cost.

Having set the goal of a structural balanced budget in the medium to long term, how would a businessperson go about reaching that aim? The main tool for budget balancing in the private sector is to contain costs, which is the firm-level equivalent of restraining government spending. In addition, businesspeople are likely to have experienced the (perceived or real) constraining effects of large bureaucracies. Such experiences, in turn, might result in an overall skeptic attitudes toward big governments,Footnote 48 thus further pointing toward a preference for EB fiscal consolidation. For example, Italian business tycoon and former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi frequently discussed the “ills” of bureaucracy and featured the need for “less bureaucracy and friendlier fiscal policy” to stimulate business activity and economic growth.Footnote 49 Likewise, in his party's manifesto, former Finnish prime minister and businessman Juha Sipilä proposed an economic program revolving around “tightened public sector expenditures, improvements in productivity [and] the removal of excessive regulations.”Footnote 50

Material interest

Scholars studying individual-level characteristics also suggest that politicians are more likely to favor policies that benefit, or at least do not harm, their professional network. Indeed, the connection makes intuitive sense considering the potential for shared frames of reference, common backgrounds, experiences, and interests. Adolph, for example, finds strong evidence that central bankers from the financial sector are more inflation averse,Footnote 51 while Witko and Friedman argue that, because of similar material interests, former businesspeople legislate more favorably towards business in the US Congress.Footnote 52 Likewise, Szakonyi (Reference Szakonyi2020) and Baccini et al. (Reference Baccini, Li, Mirkina and Johnson2018) show that Russian business leaders’ approach to regional government intervention in the economy is strongly pro-business, as in defending the interests of existing firms.Footnote 53

The interest channel is likely to play a role in former businesspeople's stance toward fiscal policy. While fiscal consolidation policies may not be directly beneficial to a country's business in the short-run, its positive effects are likely to be felt in the long-run. As long as tax-based and expenditure-based adjustments have a differential effects on businesses, the interest mechanism will affect the type of fiscal adjustment pursued. In particular, former businesspeople may be less likely to favor a fiscal adjustment policy based on tax hikes, which would negatively affect their former industry in the short term, at least considering the less costly alternative of reducing government spending. This line of reasoning is also consistent with the available survey evidence on business’ preferences. For example, Albertos and Kuo find that most Spanish firms’ executives surveyed support fiscal consolidation efforts, but only if focused on expenditure reduction.Footnote 54 At the same time, the interviewees consistently rank (high) taxes as their primary concern. Likewise, survey responses of legislative candidates in US states also reveal starkly different attitudes of business owners on a variety of issues pertaining public spending, such as welfare, regulation, economic inequality, and health care. Business owners indicate a strong preference for a smaller role of the state in all these key policy areas.Footnote 55

Self-perception

Finally, individuals with business experience may have a distinctive way to perceive themselves as particularly skilled at manipulating their environment.Footnote 56 Indeed, the psychological literature has emphasized how individuals with high levels of self-efficacy believe that they have an ability to “produce and to regulate events in their lives.”Footnote 57 Such individuals with a heightened sense of power have been found to be more optimistic, more risk-taking, and less concerned about loss of status.Footnote 58 Importantly, individuals with business experience have been repeatedly found to display higher levels of self-efficacy and feelings of power than those without business experience.Footnote 59 Indeed, we need not go far to find anecdotal examples of such behavior. For example, President Trump famously claimed that he “could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and [he] wouldn't lose voters.”

Why should a heightened sense of self-efficacy affect fiscal policy decisions? The main reason stems from the inherent uncertainty about the economic and political effects of fiscal adjustment. To begin with, while most economists agree on the long-term beneficial effects of fiscal consolidation, there is a voluminous and unsettled debate regarding its short-term effects. If fiscal tightening dampens aggregate economic output in the short-term, it will hurt politicians’ popularity. Second, aggregate considerations aside, fiscal consolidation tends to be a contentious policy, given its distributional effects.Footnote 60 While the literature on the political and electoral costs of fiscal adjustments is remarkably inconclusive,Footnote 61 it seems reasonable to suggest that there is some degree of uncertainty surrounding the economic and electoral effects of fiscal consolidation. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that policymakers generally perceive austerity as a political liability. As former prime minister of Luxembourg Jean-Claude Juncker once quipped, “We all know what to do, but we don't know how to get re-elected once we have done it.”Footnote 62 Finally, different types of fiscal consolidation policies also have heterogeneous effects in terms of economic and political costs. Expenditure-based adjustments are more likely to affect a narrower constituency which is, in turn, more capable to overcome collective action problems and mount a political challenge.Footnote 63 Moreover, expenditure-based plans are harder to design, slower to implement, and less likely to generate immediate revenue benefits.Footnote 64 Finally, expenditure-based fiscal consolidation may be more likely to increase economic inequality.Footnote 65 For these reasons, spending cuts are more likely to be a political liability than tax-based adjustments. Empirically, in one of the rare studies focusing on the type of fiscal adjustments, Jacques and Haffert find exactly that: spending cuts reduce government approval, while the impact of tax increases remains minimal.Footnote 66 Given the inherent uncertainties surrounding the costs of fiscal consolidation in general, and of expenditure-fiscal adjustment in particular, biographical factors that may affect the perception of such costs are important. Specifically, if leaders with business backgrounds exhibit a heightened sense of power and self-efficacy, they should generally be more risk-taking, thus making unpopular fiscal policies a more attractive option.

To summarize, three main mechanisms—socialization, self-interest, and self-perception—suggest that former businesspeople will be more likely to implement fiscal consolidation policies and, in particular, expenditure-based plans. Therefore, two observable implications can be derived:

H1: Compared to leaders without business experience, leaders with business experience are more likely to opt for fiscal adjustment policies.

H2: Compared to leaders without business experience, leaders with business experience are more likely to opt for expenditure-based (EB) fiscal adjustment policies.

Research design

Weakly exogenous fiscal consolidations and self-selection into office

As mentioned before, previous studies on individual-level characteristics and public debt have relied on raw measures of deficit or debt-to-GDP ratios or their subnational equivalent.Footnote 67 The problem with this approach is that the economic business cycle might affect both the country's fiscal position (and hence its baseline probability of fiscal consolidation) and its electorate's preference for business politicians. Moreover, several Western countries rely on automatic stabilizers designed to offset the negative welfare effect of the business cycle by temporarily increasing the government deficit without additional authorization by policymakers. Therefore, policymakers in power at the trough of the business cycle might correlate with changes in government finances without having done anything at all.

Leveraging close elections in a regression discontinuity framework is by far the most common approach to account for the political selection endogeneity.Footnote 68 Unfortunately, though, a regression discontinuity design (RDD) requires a large number of observations as well as detailed biographical information about both winners and losers in each election. Moreover, it is not exactly clear how to leverage the close election designs in parliamentary systems and, especially, in non-majoritarian contexts (e.g., Italy, Germany). Therefore, it is hardly feasible for broad cross-country comparisons.Footnote 69 Indeed, all the previously mentioned studies leveraging close election are at the subnational level. The recent macroeconomic literature, though, suggests an alternative strategy. Instead of directly modeling selection into office, it is possible to focus on a subset of fiscal consolidation policies that are orthogonal to the business cycle.

With this goal in mind, macroeconomists have proposed the so-called narrative approach. The idea is to rely on a careful assessment of historical documents to identify fiscal shocks that are plausibly exogenous to the economic cycle. Such historical approach is based on the following steps.Footnote 70 First, verifying that the policy documents do not discuss a desire to respond to current or prospective economic conditions. Second, within that subset of policy changes, the authors classify the official motivations stated (e.g., to reduce the budget deficit, to spur long-run growth, to restrain an overheating economy, etc.). The events are classified qualitatively based on the most relevant policy documents in each country and/or international organizations, including Budget Reports, Budget Speeches, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Economic Surveys, and International Monetary Fund (IMF) Staff Reports. The documents must “explicitly provide evidence of what policymakers believed at the time that the decisions were taken.”Footnote 71 Specifically, for the purpose of this article, I focus on (weakly) exogenous changes motivated by a desire to reduce the budget deficit. Finally, the authors track the policy changes to make sure that they were not reverted by subsequent governments and run formal econometric tests to assess the extent to which the policy changes can be predicted by current macroeconomic factors.Footnote 72

The foregoing discussion notwithstanding, the narrative approach is no panacea. Indeed, it is important to note that this approach identifies fiscal plans that are weakly exogenous.Footnote 73 A desire to reduce public deficit stems from the past deterioration of public finances. In turn, a deteriorated financial position is likely to affect other macroeconomic factors, which may be correlated with the probability of having a business politician.Footnote 74 For this reason, it is still necessary to control for the past realizations of relevant macroeconomic variables to account for the remaining sources of endogeneity. Nevertheless, as the models presented later show, most macroeconomic variables remain statistically insignificant in virtually all models, while the variables capturing the country's (past) deficit and debt remain significant. This is exactly what we would expect if the fiscal consolidation was motivated by a desire to reduce previously accumulated public debt but its timing was orthogonal to the business cycle. Indeed, this is consistent with the findings in Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi, in which the authors discuss at length the degree of predictability of the fiscal plans.Footnote 75 This limitation notwithstanding, the narratively identified fiscal policies constitute a major improvement relative to previous studies not only on methodological grounds, but also conceptually. Indeed, unlike continuous measures of budget deficits, these discrete events reflect the discretionary and deliberate decisions by governments on fiscal policy.Footnote 76

In particular, I rely on the most comprehensive and updated available dataset, which Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi constructed based on the previous work of Devries et al.Footnote 77 The dataset comprises 17 OECD countries for the period 1978–2014.Footnote 78 In order to select (weakly) exogenous fiscal consolidation measures, the authors searched for “clear sentences … … that attributed measures either to the aim of correcting the dynamics of some budgetary item … …, or to the aim of addressing the dynamics of the debt over GDP ratio, or the deficit.”Footnote 79 As mentioned earlier, I focus on fiscal changes motivated by a desire to reduce the budget deficit or, to use the authors’ terminology, to address the dynamics of public finances. The authors code both fiscal “plans” and “episodes.” The former refers to the initial government's decision to fiscally consolidate in the future (fiscal plans can be multiyear), while the latter refers to each year of fiscal adjustment as it actually took place.Footnote 80 Moreover, the authors code the size of fiscal consolidation that a given plan/episode entails, broken down by type (taxes or spending). Based on the relative amount of spending cuts and tax hikes involved, each fiscal consolidation is further coded as expenditure-based (EB) or tax-based (TB) (the two are mutually exclusive).

The empirical analysis will focus on fiscal episodes for three main reasons (see Appendix B for the results using plans). First, by focusing on episodes the analysis encompasses the complete phases of the business cycle, something that would be missed with plans. Second, the coding of fiscal plans is a bit ambiguous since it includes both genuinely new plans as well as substantial modifications to previously announced plans.Footnote 81 Since we cannot exclude the possibility that business leaders are systematically more (or less) likely to modify previous plans relative to their nonbusiness counterpart, relying on plans might bias the results in an unknown direction. Third, and most importantly, relying on episodes seems more consistent with the data generating process. Fiscal authorities decide not only to initiate a fiscal adjustment, but also its continuation, modification or cessation on a year-by-year basis.

The measurement of business experience

For practical and theoretical reasons, I concentrate on the heads of the executive. These are the most individually powerful decision makers in the executive branch of government, and, as shown in the literature review section, they exert the most significant influence on government's policy. While the individual characteristics of finance ministers may also have an effect on fiscal consolidation policies, the prime minister or the president is the one proposing (or directly appointing) the ministers.Footnote 82 Indeed, finance ministers usually make policy proposals that align with the guidelines set by the leader of the executive. Consistent with this view, the whole literature on the “strength” of the finance minister assumes that a strong finance minister is one who can reliably act as a “faithful” agent of the head of the executive.Footnote 83 As Hallerberg and Von Hagen put it, “If the prime minister prefers that the party's ideal budget be reached, which should usually be the case, she will have identical preferences on the budget as the finance minister.”Footnote 84 Indeed, the strength of the minister is usually conceptualized in terms of proximity to the head of executive and operationalized accordingly.Footnote 85 Moreover, spending priorities are often viewed as a leading example of how the leader provides direction to individual ministers.Footnote 86 Focusing on the leader of the executive also makes the results more comparable with the previous studies on individual leaders and fiscal policy.Footnote 87

The main explanatory variable is a binary indicator that takes the value of 1 for each country-year observation where the head of the executive has business experience. All mechanisms suggested in the theory section implicitly rest upon the assumption that the individual has high-level business experience. A nontrivial position in the company seems necessary for the occupational experience to influence the individual's fiscal policy preferences. Hence, I rely on the definition of Fuhrmann,Footnote 88 who recently coded all NATO leaders’ occupational experiences up to 2014. A leader is coded as such if they “established or owned a company, worked as a firm's chief executive officer, served on a corporate board of directors, or worked as a senior manager or an executive.”Footnote 89 As a starting point for the countries that are not in Fuhrmann's sample (i.e., non-NATO countries), I rely on the LEAD dataset, which provides biographical information up to 2004.Footnote 90 Unfortunately, the LEAD dataset does not provide the most appropriate coding of business experience for the purpose of the present study. For example, some leaders in the dataset did not hold high-level positions. Therefore, I recode the original business experience variable according to Fuhrmann's definition. To do so, I rely on the original sources consulted by Ellis, Horowitz, and Stam.Footnote 91 Where I could not find the information needed, I complemented the search with additional primary as well as secondary sources (academic books and articles, newspaper articles, obituaries, online encyclopedias, and national government websites).

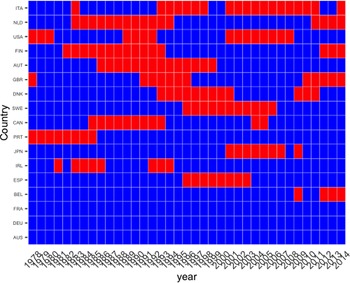

Figure 1 shows the final result of the data collection phase. The red squares indicate the presence of a leader with executive/managerial business experience in the private sector in a given country and year.

Figure 1. Heads of the executive with business experience.

Modeling strategy and control variables

To empirically test my hypotheses, I employ panel data from 1978–2014 for 17 OECD countries. I estimate the following panel data model for both dependent variables:

The main dependent variable for H1 is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for a given country-year observation if a fiscal episode took place. For H2, the dummy takes the value of 1 if the fiscal episode was expenditure based. αi is a country-specific intercept, μt denotes year fixed effects, and ɛi,t is the error term. Xi, t − 1 is a vector of lagged macroeconomic variables, and Zi,t is a vector of contemporaneous political variables. The coefficient of interest is β1.

While the narrative approach's goal is to disentangle fiscal consolidation from the business cycle, it is still desirable to control for a battery of past macroeconomic variables. Not only this allows us to account for the remaining endogeneity, but also to check if the weak orthogonality assumption is met. While fiscal adjustments may be predicted by past realizations of the deficit and the debt, most macroeconomic variables capturing the business cycle should be at best weak predictors of fiscal consolidation.Footnote 92 Hence, I control for the deficit and the interest payments on government bonds (both as a percentage of GDP) from the OECD Economic Outlook No. 97, the debt-to-GDP ratio from the IMF Historical Public Debt Database, the log of real GDP per capita (OECD Historical population data and projections 1950–2050), the unemployment rate, the inflation rate, and the real GDP growth rate (all from the OECD Economic Outlook No. 97), and trade openness as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 93

Then, I add a battery of political variables that may act as confounders. First, I include a variable capturing the government's ideology (Database of Political Institutions). In Appendix F, I further explore potentially confounding role of ideology. Second, I control for election years accounting for the potential influence of the political business cycle.Footnote 94 Importantly, the literature on fiscal consolidation has often emphasized the importance of “government strength” to explain governments’ self-selection into fiscal adjustments.Footnote 95 Moreover, given the nature of the research question, it is important to account for possible constraints on the leader's power to affect the public budget.Footnote 96 Therefore, I add a dummy to control for whether the head of government's party has a majority in all houses and a variable that captures the degree of government fractionalization (Database of Political Institutions); a variable capturing the seat share of government parties (Seki and Williams, Reference Seki and Williams2014);Footnote 97 and a veto-player index.Footnote 98 Finally, I include a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 from the year a country committed to the Maastricht criteria and a dummy for proportional electoral systems.

Empirical results

To test my two hypotheses, I estimate a set of logit fixed-effects models. To ease concerns about suppression effects of the variable of interest due to the inclusion of control variables, I include the covariates sequentially. Moreover, to account for temporal dependence between events, I include the cubic polynomial approximation of spell-time.Footnote 99 Model 1 shows the simple bivariate relationship with time and country fixed effects. Model 2 includes the economic variables, and Model 4 adds the political variables. Given the recently debated limitations regarding the estimation and interpretation of two-way fixed effects with staggered and discontinuous treatment,Footnote 100 I also show the complete model without year fixed effects (Model 3). In Appendix D, I confirm the robustness of the results using the counterfactual estimators proposed by Liu, Wang, and Xu.Footnote 101 Subsequent tables show the same four-model structure.

As Table 1 shows, H1 is by and large confirmed. Business experience remains positive and statistically significant across all specifications. Substantively, the full model predicts an increase of 27 percentage points in the probability of a fiscal episode for countries with a business leader as their head of the executive. The effect is sizeable. For comparison, consider that an increase of the deficit ratio by 3 percentage points (the limit explicitly mentioned in the Maastricht Treaty in the 1990s for joining the Eurozone) increases the probability of fiscal consolidation by 24 percentage points. Importantly, we should notice the lack of statistical significance of most economic variables capturing the business cycle. This nicely shows the strength and validity of the narrative approach to identify fiscal consolidation policies. A similar pattern arises in the rest of the models.Footnote 102 Moving on to Table 2, we see that H2 is also confirmed. Substantively, the full model predicts a 9 percentage point increase in the probability of enacting an expenditure-based fiscal adjustment when the country's leader is a former businessperson. The effect is roughly equivalent to an increase in the deficit ratio by 2 percentage points.

Table 1. Logit fixed-effects models: Fiscal consolidation

Note: Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

∗ p < .10; ∗∗ p < .05; ∗∗∗ p < .01.

Table 2. Logit fixed-effects models: Expenditure-based fiscal consolidation

Note: Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .10; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

One possible objection is that, while business leaders consolidate more often than their nonbusiness counterparts, they may also enact smaller fiscal adjustment packages. This, in turn, would cast doubts on the substantive implications of these findings. As I show in Appendix A, though, this is not the case. Actually, business leaders tend to enact larger fiscal consolidation packages and deeper government spending cuts, although the effect is small and not statistically significant.

Endogeneity and inferential threats

The key assumption of this article is that business leaders’ selection into office and the decision to fiscally consolidate are not driven by other factors. So far, the research design has dealt with the potential confounding role of third factors with a combination of covariate-adjusted regressions and the identification of weakly exogenous fiscal episodes via the narrative approach. In Appendices D and E, I provide further evidence to support this assumption. Admittedly, though, my strategy remains imperfect as it cannot fully account for unobservable confounders. Business politicians’ selection into office and fiscal policy choices may be affected by the institutional environment, political party strategy, and/or the electorate's preferences. These factors, in turn, may also affect a country's fiscal policy.

Previous research on developing countries at the subnational level shows that businesspeople tend to enter politics to avoid the cost of lobbying in an environment with weak democratic and market-supporting institutions.Footnote 103 In contrast with this literature, though, this article is concerned with the role of business politicians in environments with robust democratic institutions. While we cannot exclude the possibility that subtler variations in the institutional environment may still matter,Footnote 104 the rich set of political controls included in the full models should mostly account for this channel.

Regarding the role of political parties, a potential concern is that the fiscal policy under a businessperson's government may reflect the leader's political party affiliations rather than their professional experience. Indeed, previous research has found that while a candidate's business label may not matter much at the aggregate level, it might be appealing to conservatives.Footnote 105 If conservative fiscal preferences are part of those parties electoral brands (as it is likely), businesspeople may be more likely to be selected as the party's official candidate. In light of this, all full models control for government ideology throughout the article. In Appendix F, I further investigate whether business and nonbusiness leaders systematically differ in terms of ideology. First, I rerun the main models including an alternative indicator of individual leader's ideology (rather than government's ideology) borrowed from the recently published Global Leader Ideology dataset.Footnote 106 Second, I formally test for the relationship between ideology and business experience using a test of equality of proportions across ideological groups, which yields statistically insignificant results in both cases.

Finally, the role of voters is arguably the most pressing endogeneity concern. For example, the electorate may favor business candidates over nonbusiness candidates as they expect the former to fiscally consolidate. If leadership change (and tenure duration) is endogenous to voters’ fiscal preferences, policymakers may simply be faithful agents of the principal's (the electorate) preferences. In Appendix G, I further illustrate this identification problem in the concrete case of US presidential elections (1940–2012). While we would need a more sophisticated and fine-grained analysis to ascertain the true determinants of businesspeople's decision to run for office, we may interpret those results as indicative of leadership changes being at least partly endogenous to fiscal preferences among the electorate, thus raising concerns about the true source of causality.

Given the aforementioned concerns, an RDD that leverages close elections would be ideal to identify a clean causal estimate of business experience. As mentioned before, data limitations make the approach hardly feasible in this context. There is only a handful of close elections that could be leveraged for inferential purposes. This is not surprising since most countries in the dataset have parliamentary systems, whereby the electoral margin does not provide a discontinuity at the threshold. Nevertheless, we can gain some insights by utilizing an RDD on a broader sample. Conveniently, in a recent paper, Carrière-Swallow and colleagues follow the same approach as Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi to identify fiscal consolidation episodes in Latin and Central America since 1989.Footnote 107 As these countries tend to have presidential systems, we can leverage a few more observations. To identify electoral margins for these cases, I rely on the data collected in Bertoli, Dafoe, and Trager.Footnote 108 The dataset provides the popular vote electoral margin for presidential and semipresidential elections for the period up to 2010. Following standard practice in the literature, an election is considered close if the two top candidates are within 2 percent. In cases in which there is a runoff, the vote shares of the runoff is used. To this new sample, I also add South Korea, another semipresidential system for which there is data on fiscal consolidation from Yang, Fidrmuc, and Ghosh.Footnote 109 For all new countries, I rely on Ellis, Horowitz, and Stam's coding of business experience as described earlier.Footnote 110

The results provided here should be viewed as tentative for several reasons. First of all, the measurement of fiscal consolidation episodes comes from three different sources.Footnote 111 While the studies by and large follow the same approach, some degree of discretion in identifying the underlying motivations for fiscal consolidation is probably unavoidable. Second, a full-fledged RDD would require a larger number of observations as well as detailed biographical information about both winners and losers in each election. Even after extending the dataset as described above, there are only nineteen close elections. In six cases, the election's winner was a business politicians. Detailed reliable biographical information about the losers are hard to come by, above all in the case of developing countries.Footnote 112

For these reasons, I employ a more straightforward approach and look at the subsample of leaders that won office by a close margin. Hence, while relying on close elections to identify as-if random transitions, the approach is inspired by studies focusing on sudden death in office.Footnote 113 Given the as-if random nature of the subsample and its small size, I do not include covariates. I test the as-if randomness assumption in two ways. First, I check the balance in pre-treatment outcomes by regressing fiscal consolidation episodes in the pre-electoral period on a binary indicator capturing the (future) tenure of a business leader. The coefficient is statistically insignificant, thus indicating no systematic differences in the pre-electoral outcomes of close elections won by business politicians relative to close elections won by nonbusiness politicians. Second, I check whether business leaders are more likely to win by a smaller margin within the +/–2 percent threshold, which may indicate sorting around the threshold. A t-test of mean differences in the electoral margin of business politicians relative to nonbusiness politicians also yields a null result.Footnote 114

Given the small sample, the panel data structure (in Model 1 at least), and the relative rarity of the event, I opt for a linear probability model over a logit.Footnote 115 Model 1 below shows the results from the relationship between business experience and fiscal consolidation episodes for the full tenure of leaders following a close election. I model country-level unobserved heterogeneity via random effects.Footnote 116 Model 2 shows the results at the individual leader level. The dependent variable in this case is the sum of fiscal episodes during tenure divided by the years in government following the close election. The coefficients in both models in Table 3 are statistically significant and remarkably similar to the marginal effects derived from the logit coefficients in Table 1.

Table 3. Close elections subset: Fiscal consolidation

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .1.

Fiscal policy in Canada under Brian Mulroney (1984–93)

The historical case of Canada between the mid-1980s and early 1990s further illustrates the argument. The period encompasses the two Canadian governments led by Brian Mulroney (1984–88 and 1988–93). Mulroney turned to the private business sector after an initial and promising career as a lawyer. He eventually became the president of Iron Ore Canada (IOC) in 1976, a position he kept until his decision to run as the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party in 1983.

I choose this particular case for three main reasons. First, this historical period in the Canadian context was characterized by a low salience of budget considerations among the public relative to the following period in the 1990s. Appendix I shows how the percentage of Canadian respondents identifying the budget as the most important problem increased only after the second Mulroney government.Footnote 117 Moreover, previous research has shown that Canadians tended to prefer a loose fiscal policy and to reward governments running deficits until around 1993–94, when the downgrading of the Canadian government's sovereign debt by credit rating agencies and the subsequent Mexican peso crisis brought the issue to light.Footnote 118 Thereafter, citizens’ deficit bias morphed into a balanced budget bias, with Canadians’ approval of the government increasing following deficit reductions.Footnote 119 Hence, this case selection guards against the inferential threats attributable to the possible endogeneity of leadership change and tenure to the electorate's (conservative) fiscal preferences.

Second, Mulroney was a particularly powerful prime minister, whose ability to directly and/or indirectly influence fiscal policymaking is well documented.Footnote 120 This, in turn, makes it an ideal case as it “controls” for the possibility that other important actors (e.g., the minister of finance) were the main drivers of fiscal policymaking.

From a practical standpoint, this case offers a further advantage. The life of Mulroney—before, during, and after his tenure as prime minister—is well documented in several sources, including academic books and papers, official and unofficial biographies, and autobiographies of the main actors involved.Footnote 121 Moreover, fiscal policymaking in Canada during that period is discussed extensively in several studies.Footnote 122 The September 1984 election proved to be a watershed moment in Canadian history and the end of an almost twenty-year hegemony of the Liberal Party and, beginning in 1968, of its charismatic leader Pierre Trudeau.Footnote 123 Mulroney won election again in 1988 and remained in power until 1993. The main thrust of fiscal policymaking, which emphasized the need for expenditure-based fiscal consolidation, remained consistent throughout this period.Footnote 124

Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi identify twenty fiscal consolidation episodes in Canada between 1978 and 2014.Footnote 125 Of these, nine (45 percent) were implemented under Mulroney. Of these nine episodes, seven (78 percent) were expenditure based. In the economic realm, and in fiscal and budget policy in particular, Mulroney's government is characterized in the scholarly literature as particularly proactive, “unveiling one reform after another, virtually from the day it assumed office.”Footnote 126 Such an interventionist stance was facilitated by the fact that, during this period, the process of centralization of power in the hands of the prime minister reached its peak. According to contemporaneous accounts, an “increased concentration of power under the prime minister” was the “most important organizational implication” during Mulroney's first year in office.Footnote 127 Rather than simple prime ministerial presence in the collective decision-making bodies, it involved “a significant personal intervention in those areas of priority to the prime minister and his government. The prime minister in this sense becomes the principal counterweight to ministerial ambitions that are not in accord with his policies, priorities or strategy.”Footnote 128 In other words, the center of government had come to belong “to the prime minister and not to ministers, either collectively or as individuals.”Footnote 129 As a senior minister of the succeeding Liberal government observed, the cabinet had by then become “a focus group for the PM.”Footnote 130 While the prime minister's prominence—both because of the political institutional environment and because of Mulroney's personal charisma and skills—in setting the broad directions of fiscal policymaking seems clear, the case study also reveals a potential means through which business politicians may implement a balanced budget: the appointment of former businesspeople in key positions at the ministry of finance. Indeed, Finance Minister Michael Wilson—who as a child found the greatest inspiration in the biographies of businessmen Andrew Carnegie and J. P. MorganFootnote 131—was an accomplished businessperson in the investment banking sector in his own rights before deciding to engage in national politics. According to several sources, Wilson acted as an effective and loyal finance minister in charge of laying out a pragmatic and gradualist approach to deficit reduction based primarily on expenditure cuts.Footnote 132

In laying down his public stances, Mulroney was quite explicit in tracing his beliefs to his private sector experience, consistent with the socialization channel underlined in the theory section. His experience in the mining industry had proven to be quite successful. By the time he took the presidency in 1976, the company was suffering from tense labor management relations, low productivity, and high costs. By the end of his tenure, the situation had been reversed and IOC shareholders “collected more dividends in five years than they had in the previous twenty.”Footnote 133 According to Mulroney, “the control of costs”—in addition to improved labor relations, a renewed work ethic, and productivity increases—figured prominently in IOC's “formula for … … success.”Footnote 134 It was during this formative period, as Mulroney recalled in his memoir, that the businessman “developed skills, talents, interests, and aptitudes hitherto unknown to me. They were extraordinarily beneficial … … when I became prime minister.”Footnote 135 Not only did those “skills, talents [and] interests” nurture his overall approach to policymaking, they would also lead him to identify the main economic issues facing Canada: “I was able to begin the process of thinking through some of Canada's problems and elaborating realistic proposals to deal with them. … … Through my participation in the business world, I began to understand the damage the Liberal government had inflicted—and was continuing to inflict—upon the Canadian economy.”Footnote 136 Likewise, a few months before the 1984 elections, he remarked, “Coming to Ottawa from the private sector, I have been appalled by the waste of time and talent in government” and pledged, if elected “to challenge on-going programs.”Footnote 137

Once in office, Mulroney brought a new approach to government, partly inspired by the contemporaneous experiences of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but also arguably influenced by his own experience in the private sector. While criticisms about the lack of specific policy objectives when he became prime minister in 1984 abounded in the press, one thing was clear: Mulroney favored restraint in government and a greater dependency on the private sector to generate economic growth.Footnote 138 This new approach “sought to transform public administrators into managers who could think, act, and perform like private managers and run the government operations like private concerns.”Footnote 139 Not unlike his American and British counterparts, Mulroney forcefully contended that “the state, and particularly the fiscal deficits that symbolized its alleged excesses, was the economic problem.”Footnote 140 As he made clear to his ministers at the opening of his first cabinet meeting, the cornerstone of this new approach was fiscal consolidation: “There is no money for many of the new programs that you thought you came here to promote. There will be new money to spend on programs eventually if we continue to act responsibly in fiscal matters. But first we must make inroads in the mountain of debt.”Footnote 141 At the same time, though, his approach to deficit reduction—pragmatic in nature rather than ideological, gradualist/middle of the road rather than abruptFootnote 142—set him apart from his contemporaneous colleagues Reagan and Thatcher.Footnote 143 It also meant that, while balancing the budget always remained the hallmark of the government's fiscal policy, the prime minister—“a master of negotiation, compromise, and reconciliation”Footnote 144—often displayed a willingness to compromise on how to reach the final outcome.Footnote 145 As a senior cabinet member of Mulroney's government suggested, his previous experience in the private sector likely played a role in shaping his pragmatic approach: “He likes to cut a deal. That is what he did for a living before he came to politics.”Footnote 146

Overall, the case of Mulroney seems to support the observable implications of the theory as well as the main hypothesized channel, socialization effects. What about the remaining two channels through which businesspeople may have systematically different fiscal preferences—material interest and self-perception? Unsurprisingly, clear statements linking the prime minister's preferences exclusively to the material interests of the business community are hard to come by in Mulroney's autobiography (and in the other cabinet members’ own recollections). Nevertheless, according to several sources, there is little doubt that the government's fiscal policy choices were by and large consistent with business preferences.Footnote 147 For example, one of the main targets of the Canadian business community had been Canada's Unemployment Insurance (UI) program, long denounced as too expensive and an hindrance to the country's productivity. Upon assuming office, Mulroney established (and chaired) a commission—which would eventually recommend a $3 billion cut—to review all public expenditures related to UI.Footnote 148 This is consistent with Mulroney's own recollections of the most controversial parts of the 1988 proposed federal budget: “The business community would support our efforts, maybe even muttering to themselves how brave and stalwart we were … … But virtually everyone else … … would absolutely hate it.”Footnote 149 Moreover, it is worth noting how Mulroney justified his government's fiscal policy failures as the result of the lack of support by the business community. In explaining the failed attempt to rein in government spending by de-indexing Old Age Security from inflation protection, he lamented being “abandoned by everyone, ranging from Conservative premiers to the leaders of business groups, the timing of whose opposition dealt us a significant blow and left us—perceptually at least—bereft of allies.”Footnote 150

Finally, a historical case study may not be the best tool to investigate businesspeople's perceptions of the costs of fiscal adjustment. Indeed, any actor directly involved in a government—let alone the prime minister himself—is likely to have an incentive to depict themselves as “brave and stalwart” politicians carrying on (misguidedly) unpopular policies notwithstanding their potential electoral and political consequences.Footnote 151 In other words, the incentive here is to emphasize, rather than downplay, the costs of fiscal consolidation. And indeed, this is what we find in Mulroney's memoir when discussing the thorny issue of public debt: “The more we did to avert the coming financial disaster, the more enemies we would make.” And, again, “as I learned to my cost, every brick that we removed from that debt-creating edifice provoked howls of outrage from that constituency. Taking away a benefit—un droit acquis—was always unacceptable, even if the benefit was unaffordable.”Footnote 152 At the same time, though, Mulroney himself—in the recollection of his finance minister—hinted at an intriguing reason for why businesspeople may perceive lower (personal) costs due to fiscal consolidation: “Mike, you and I are here to make a difference. We can always get a good job elsewhere. That's a given. But we're in government to change things for the better. If we weren't, we might as well go back to the private sector and make ourselves a little money.”Footnote 153 In other words, the underlying source of businesspeople's relatively greater risk-taking attitudes in public policy might be the lower opportunity costs of losing office.

Overall, the case study illustrates quite a few aspects laid out in the theory section. First, it shows the influence of professional socialization on fiscal (and, more generally, economic) preferences. Second, it provides some evidence for the importance of support from the business community, the lack of which explains Mulroney's turnaround on some key fiscal issues. At the same time, it also reveals some new features that may characterize the relationship between business politicians and fiscal policy preferences. On the one side, it suggests a channel through which a businessperson may enact their favorite fiscal policies—that is, by appointing an individual with similar professional experience (and, as a result, similar preferences). On the other side, it reveals why at least a subset of business politicians—those whose business experience is recent and whose connections with the business world still strong—may be well positioned to sustain the uncertain consequences of fiscal consolidation, by leveraging their “exit” option to return to the private sector and make, to paraphrase Mulroney, a little extra money.

Conclusion

Political economists often assume that the only genuine preference of politicians is to behave opportunistically to maximize their probability to remain in power. As a result, executive-level fiscal preferences have received scant attention in the literature, with the partial exception of ideology. This article employs a different approach. Combining insights from sociology, political science, psychology, and business studies, I draw a connection between politicians’ experience in the business sector and fiscal preferences. I hypothesize that business politicians may be more prone to enact fiscal consolidation—and to rely more heavily on expenditure cuts than tax hikes—because of socialization effects, material connections, and psychological factors. I test the two hypotheses using data from 17 OECD countries over the 1978–2014 period and on a broader sample of semipresidential and presidential systems. Methodologically, I ease the endogeneity concerns raised in the previous literature in two ways. First, I focused on a subset of fiscal consolidations that are weakly exogenous to the business cycle. Second, I further probed the causal nature of the relationship analyzing a subset of as-if random elections. Consistent with the theory, the results suggest that having a head of the executive with a business background increases the probability of fiscal consolidation and expenditure-based fiscal consolidation by an amount comparable to meaningful variations in well-known economic determinants of fiscal adjustments, such as the deficit-to-GDP ratio. Finally, I complemented the statistical analysis with an illustrative case study of Brian Mulroney's governments in Canada (1984–93).

In recent times, political economists have increasingly recognized the significance of leaders in shaping economic outcomes. However, empirical studies examining leader variables often lack well-established theoretical frameworks, leading to mixed empirical evidence. The findings presented here add to an expanding field in the literature, demonstrating that political leaders can exert substantial influence on the economic performance of their countries. This article also shows that by incorporating theoretical perspectives developed in different social science fields into the examination of economic issues, we can enhance our understanding of the transmission channels linking leaders’ characteristics and their economic policy stance. Finally, the analysis cautions against “naive” approaches to endogeneity concerns. While the different occupational backgrounds may affect a (future) leader's preferences over economic policy, it behooves researchers to account for the various actors that might affect the leaders’ probability to be in a position of power.

An intriguing avenue for further exploration would be to examine whether the professional backgrounds of finance ministers have an impact on fiscal policymaking, as well as investigate potential variations in the influence of politicians across different policy fields. Moreover, different types of heads of governments may select ministers with varying characteristics, as evidenced by the case study of Canada under Mulroney, leading to potential interactions. A further extension would imply analyzing more disaggregated spending and tax policies. For example, while business leaders tend to enact expenditure-based fiscal policies on average, they may refrain from cutting certain spending items (e.g., research and development) that are ore likely to be beneficial to the business community. The analysis presented here serves as a foundation for numerous captivating inquiries regarding the influence of politicians’ business backgrounds on fiscal policy outcomes.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank David Leblang, Sonal Pandya, Aycan Katitas, Ben Helms, Melle Scholte, and all participants at the 2021 Graduate Student in International Political Economy Workshop and the 2021 American Political Science Association Annual Conference for their invaluable comments on this article.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study will be available from the corresponding author's website.

Competing interests

The author(s) report there are no competing interests to declare.

Funding statement

The author(s) declare no funding.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2023.24