The search for knowledge, said a modern Chinese philosopher, is a form of play. Very well: we want to play with spaceships.

Arthur C. Clarke, 5 October 1946Footnote 1

Space exploration has become central to the much-vaunted ‘China Dream’. Since 2016, under the slogan ‘Foster space spirit, explore the starry universe’, an official ‘Space Day’ has been celebrated nationwide every 24 April, the day when China’s first satellite, Dongfang Hong (East Is Red) 1, launched to great fanfare in 1970.Footnote 2 For the fiftieth anniversary of this epoch-making event, the government issued a statement explaining why space technology took such a high priority on the political agenda. ‘The development of spaceflight has become the symbol of the times for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’, the official newspaper People’s Daily explained.Footnote 3 As the pinnacle of technological prowess and the epitome of technoscientific modernity, the development of spaceflight capacities demonstrates China’s formidable state power to the world. Alongside Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Xi Jinping, the statement mentioned only one other individual: scientist Qian Xuesen (1911–2009, also known as Tsien Hsue-shen), the widely hailed ‘king of rocketry’ and ‘father of spaceflight’. Hardly known in the West outside expert circles, Qian is both China’s science superstar and a household name. Children hear about his achievements while learning to read and write.Footnote 4

Yet Qian’s fame as the country’s undisputed face of space is of surprisingly recent origin. In 1990, the best-known Chinese astronautical engineer to date was heralded in a propaganda poster (Figure 1). Although declining as a popular medium since the early 1980s, in their heyday such posters easily reached a circulation of 10,000 to 50,000 copies.Footnote 5 Dressed in blue trousers and a yellow shirt, with an overcoat casually thrown over his shoulders and holding his spectacles before him, the tall and sturdy Qian dominates the peaceful autumn scenery, presumably part of the Xichang launch site in south-west China. Standing in a valley to Qian’s right is the famous three-stage Changzheng (Long March) 3 rocket, first introduced in 1984. An earlier model in the same family had carried the 173-kilogram Dongfang Hong 1 satellite. All preparatory works appear to be completed, and Qian’s stance conveys tranquillity, pride and optimism to his audience. The overall cool colours signal the transition from socialist revolutionary models, often portrayed in warm tones, to a new type of post-socialist hero who advanced China’s modernization through science and technology. Firmly rooted on the ground with only his head in the blue skies, Qian Xuesen, with the help of rocket technology, is able to reconcile the heavens and the Earth – dingtian lidi – and, for this spectacular feat, he commands the viewer’s admiration.

Figure 1. Propaganda poster of Qian Xuesen standing in an idealized autumn landscape with a three-stage Changzheng (Long March) 3 rocket in the background. Li Huiquan, Zhonghua haoernü: Qian Xuesen (Excellent Sons and Daughters of China: Qian Xuesen), n.p.: Sichuan Meishu Chubanshe, November 1990. Courtesy Stefan R. Landsberger Visual Documents Collection, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

Echoing the iconic Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan painting (1968), the carefully staged pastoral mise-en-scène linked Qian’s persona with China’s revolutionary past and future, in the form of its spaceflight programme as a source of unlimited national rejuvenation.Footnote 6 Born on 11 December 1911, less than a month before the formal establishment of the Republic of China (ROC), the first post-imperial regime in Chinese history, Qian supposedly experienced the same vicissitudes as the nation itself, from semi-colonial status to independence upon the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. To this day, national media continue to align his rise with that of the so-called new China, conjoining technoscientific glory and military prowess. In this process, spaceflight technology was both cause and effect.

This article interrogates the social, cultural and political rationale behind the making of a space persona, particularly after Qian Xuesen’s controversial departure from the United States in 1955. It charts his transformation from aeronautical engineer known only within expert circles to China’s foremost rocket star, especially after the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests crackdown on 4 June 1989, and deconstructs the making of a father figure, space patriarch and technoking. Like Yuri Gagarin in the Soviet Union, Sigmund Jähn in East Germany and Arnaldo Tamayo in Cuba, communist technocelebrities such as Qian elicited public pride, evoked patriotism and confirmed the system’s superiority.Footnote 7 However, unlike Gagarin and Jähn, this Chinese superstar remains virtually unknown outside China, even among space historians.Footnote 8

‘Who is Qian Xuesen?’ asked an English-language children’s picture book, published in 2022 as part of a Figures in China’s Space Industry series.Footnote 9 The present article attempts to answer the same question without reverting to an either biographical or hagiographical approach. Asking how the figure of Qian Xuesen became today’s pre-eminent Chinese technocelebrity and what role rocket technology, space imaginaries and a particularly Chinese variant of astroculture played in this process, it interrogates the personification of a national space programme through a larger-than-life father figure and analyses the making of a global space persona bar none.Footnote 10 Ultimately, this article argues, Qian’s meticulously crafted persona constitutes what Ernesto Laclau has termed an ‘empty signifier’: a placeholder that ostensibly unifies disparate views yet, in its divergent understandings, is ultimately devoid of meaning.Footnote 11 As such, Qian’s persona embodies a unifying symbol, drawing strength from its ambiguity and interpretive flexibility. In China, Qian has come to stand for space, and space for Qian, but little else.

Who is Qian Xuesen?

Since the publication of the above poster over three decades ago, Qian Xuesen has been subject to myriad biographical treatments, predominantly in Chinese. The key facts of his life have been told repeatedly. Qian received a Western-style education at Shanghai Jiaotong University, majoring in mechanical engineering. In 1935, aged twenty-six, he set out for graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as a beneficiary of the Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Fund that sponsored Chinese students to study in the United States. Working under noted Hungarian American aerodynamicist Theodore von Kármán (1881–1963), Qian obtained his doctoral degree in 1939 from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. For two decades, Qian was a flourishing Chinese American scientist: founding member of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), expert consultant for the US Army Air Forces and after 1949, when he was preparing for his US citizenship application, Robert H. Goddard Professor of Jet Propulsion at Caltech.Footnote 12 Qian’s departure from the United States on 17 September 1955 and subsequent resettlement in the PRC, following five years of FBI investigation during the McCarthy era, constituted a stark biographical caesura. Welcomed by the new China, Qian seamlessly metamorphosed from being ‘completely apolitical’ into a ‘red scientist’ and hardline politician, to the surprise of his former US colleagues. Qian was ‘not the same man who left the US in 1955’, one of them remarked later.Footnote 13

What did not change were Qian’s astrofuturist convictions. ‘We are at the eve of a real air and space travel era’, he proclaimed in 1956. ‘Tomorrow will be another era of human civilization. It’s the era of satellite and spacefaring. This is the actual future of space technology.’Footnote 14 China’s missiles and space programme and Qian’s career rose in parallel. He instantly became director of the new Fifth Academy under the Ministry of National Defence and one of the institutional precursors to the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) founded in 1968; he oversaw China’s first generation of ballistic missiles as part of the Two Bombs, One Satellite project during the 1960s; and he helped launch the Dongfang Hong 1 satellite in 1970. ‘He was seen as a symbol for the entire Chinese space effort: something akin to being the nation’s Wernher von Braun’, his American biographer, Iris Chang, has noted.Footnote 15 As the top military science adviser to Mao Zedong and the CCP, Qian was, by some accounts, ‘the most powerful scientist in the country’.Footnote 16

Research on Qian Xuesen conducted within China contrasts sharply with that undertaken elsewhere with regard to motivation, focus and timing. While sketches of his scholarly achievements and personal life in the United States focused on his 1955 return home, the Chinese public only began to learn about him in earnest through the burst of celebrity life writings in the 1980s. When Qian was awarded State Scientist of Outstanding Contributions in 1991, the highest honour a Chinese scientist can receive, his former secretary, Wang Shouyun, published a six-page ur-biography in People’s Daily.Footnote 17 Ten years later, following another national distinction as People’s Scientist, Qian’s research assistant, Tu Yuanji, authored a comprehensive biography, later abridged for the Biographies of Personalities in CCP History series.Footnote 18 Catalysed by these accounts, writers without direct access to Qian have published a plethora of unauthorized biographies since the mid-1990s, often recycling, expanding and even plagiarizing official biographies, media reports and public hearsay.Footnote 19 Collectively, these life writings have apotheosized Qian through reiterations of a repertoire of anecdotes and motifs.

After Qian’s death in 2009 and as a consequence of the opening of the Qian Xuesen Library and Museum two years later, scholarship on his life and career in China expanded. Institutionally part of his alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University, and funded by the Propaganda Department of the CCP in Beijing, the museum has amassed historical documents ranging from manuscripts and letters to photographs and poetry. Its vast collection includes Qian’s former library, newspaper clippings, artwork and copies of documents gathered from archives and libraries worldwide, totalling 76,000 items, 1,500 pictures and 700 objects.Footnote 20 Since 2016, eight issues of Qian Xuesen Studies, a peer-reviewed research-oriented journal, have been published. More than twenty monographs subsidized by the museum explore his impact on China’s tech-oriented universities and research institutions.Footnote 21 This ever-growing body of largely non-critical scholarship perpetuates and expands the established hagiographic narrative. Acting as incubator and gatekeeper, the museum both contributes to and benefits from Qian’s ongoing celebrification.

In contrast, research undertaken outside China has predominantly focused on Qian’s twenty-year tenure in the United States (1935–55). For four decades, interest was limited to a few newspaper articles and magazine portraits. On the occasion of China’s first nuclear-weapon test in October 1964, the New York Times featured Qian’s name on its front page and included his portrait in its ‘Man in the news’ section. Look and Esquire magazine profiles followed in 1967.Footnote 22 It was this Esquire profile of the ‘evil genius behind Red China’s missiles’ that first spotlighted the political circumstances of Qian’s departure, circumstances that still dominate non-Chinese Qian scholarship. His potential membership in the Pasadena Section of the US Communist Party proved the key question and litmus test: Was Qian’s 1955 departure effectively a deportation, and as such the ‘stupidest thing this country ever did’, as US Undersecretary of the Navy Dan Kimball would have it?Footnote 23 Or was he the lost son, humiliated by legal complications in the United States, finally willing to listen to the young republic’s needs and rush back to his motherland’s assistance? Whether pushed or pulled, the answer depends on one’s political perspective, and might be less important than is conventionally assumed.Footnote 24

The situation changed fundamentally in 1995 with the publication of Iris Chang’s Thread of the Silkworm, the first book-length biography written in English and hitherto the only historico-critical study to meet scholarly criteria.Footnote 25 Utilizing extensive research and numerous interviews with Qian’s colleagues and companions in the United States and China, Chang wove a detailed tapestry of Qian’s life and activities. Given the inaccessibility of both Chinese archives and Qian himself, Chang devoted twenty-three of twenty-five chapters to his formative years prior to 1955, and only the last two chapters to his ‘second life’ in China. Without definitive evidence for Qian’s membership in the US Communist Party, the book inadvertently cemented his controversial departure as the crucial, albeit elusive, key to understanding the ‘real’ Qian.Footnote 26

Recognizing his larger-than-life persona in contemporary China, historians have only recently begun to rediscover and reassess the historical Qian, particularly as a central node within the volatile scientist–state relationship, and as a power broker at the intersection of the history of science and technology, and media and literary cultures. Bypassing a (meta)biographical approach, these works situate Qian Xuesen in the contexts of the global Cold War and the CCP’s changing science policy, seeing him as one of many actors to evaluate China’s strategic modernization and other national programmes, such as the notorious one-child policy.Footnote 27 With the exception of a 2011 article by historian Ning Wang on the propaganda campaign to ‘commend and eulogize’ Qian’s life, his role – both real and attributed – in establishing a highly successful spaceflight programme has not been part of this rediscovery process.Footnote 28 The motives, strategies and uses of creating a global space persona have not been examined, nor has Qian’s apparently unstoppable rise been noticed in the West. Available histories of the Chinese space effort limit themselves to policymaking, institution building and techno-nationalism, and there is a complete dearth of literature on Chinese astroculture, space enthusiasm and the societal impact of spaceflight.Footnote 29

Conjunctures of celebrification

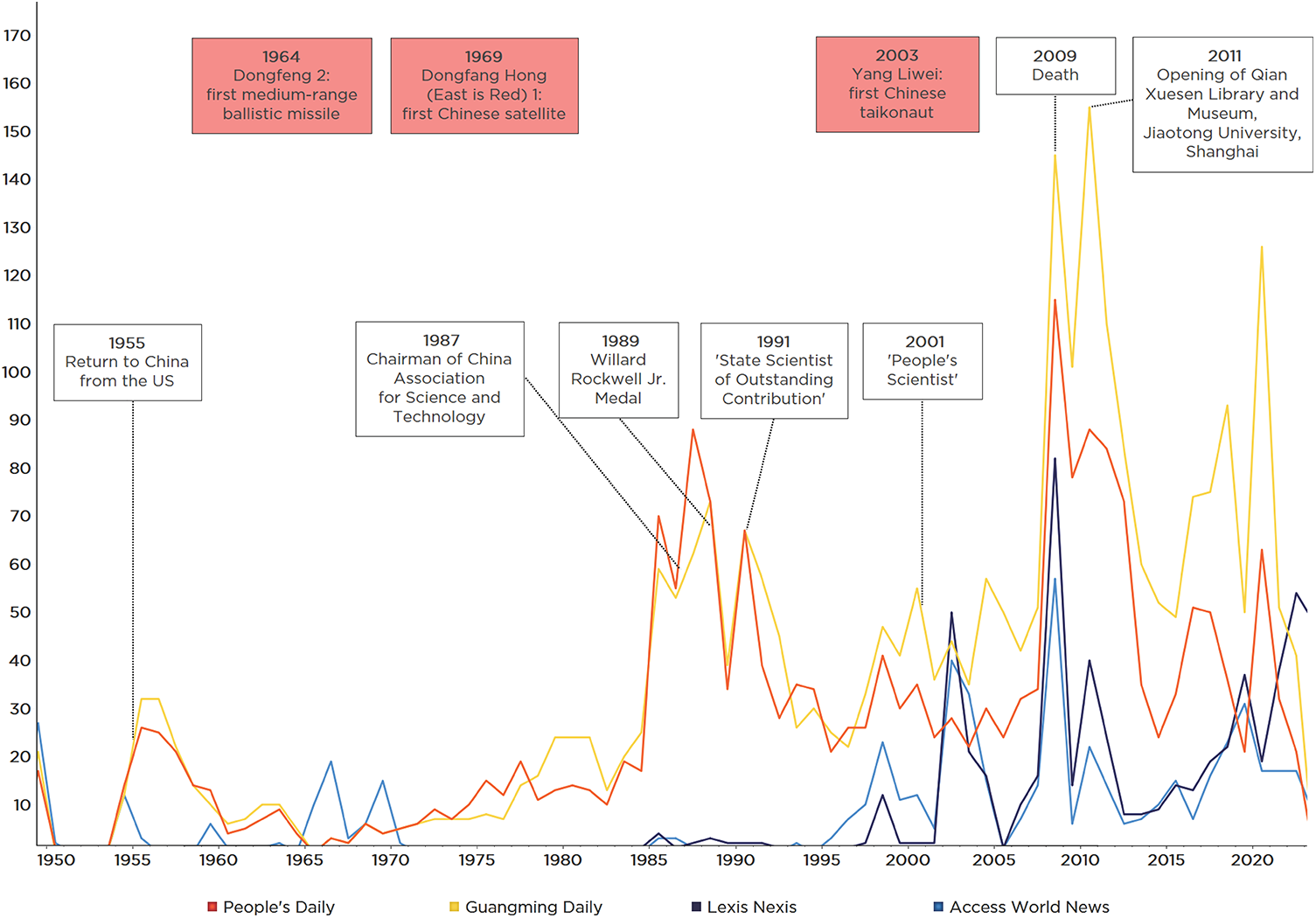

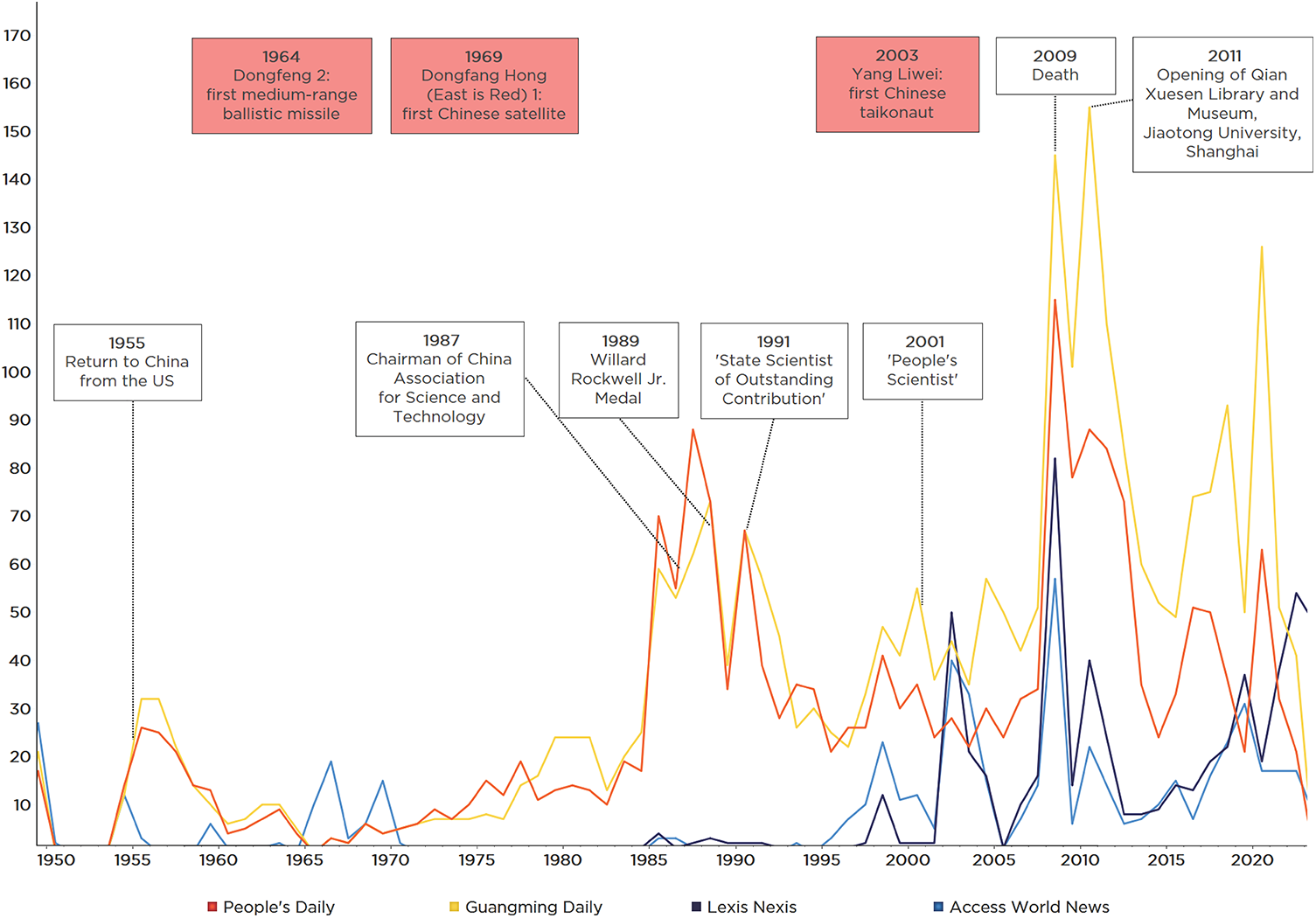

Newspaper reporting has been as much a driving force behind Qian’s celebration as it is an indicator of his changing presence in the Chinese public realm. Consequently, his seemingly inexorable ascent is particularly evident in newspaper coverage, especially after 1989. To trace Qian’s emerging persona, we have tracked mentions of his name in the two largest Chinese newspapers, People’s Daily and Guangming Daily, both CCP-controlled, and in LexisNexis and Access World News, two aggregated databases for non-Chinese coverage, from 1950 to today.Footnote 30 As Figure 2 shows, three peaks can be identified: 1954–7, 1985–92 and 2009–12. By comparison, international press coverage has been more restrained, with significantly lower spikes in the late 1980s, in the mid-2000s, together with China’s first human spaceflight mission in 2003 and his biographer Iris Chang’s much-reported suicide in 2004, and in the aftermath of Qian’s death in October 2009.

Figure 2. National and international media interest in Qian Xuesen, 1950–2023, in relation to key biographical moments (white boxes) and China’s ‘space firsts’ (red boxes). Data gathered from occurrences of Qian Xuesen’s name in People’s Daily, Guanming Daily, LexisNexis and Access World News. Graph by Raven M. Davis, Georgia Institute of Technology.

Qian’s much-acclaimed return in 1955, after a two-decade lacuna, led to a short-lived peak in newspaper reporting in China. As Chang noted, during the ensuing period, largely devoted to institution building and, with Soviet help, the establishment of a future missile and space industry, there was little news coverage of his activities.Footnote 31 Certainly, Qian was not shrouded in the same secrecy as Soviet ‘chief designer’ Sergei Korolev prior to his death in 1966.Footnote 32 Yet if Qian’s name appeared in print it was mostly in contexts of minor significance, for instance intermingled with other scientists in conference reports, or as a spokesperson for the rocket program, without offering much additional information, let alone personal detail.

The situation changed in the mid-1980s, with a rapid rise in media attention lasting through the early 1990s. Unlike in the West, where post-Apollo hopes for a space enthusiasm revival were thwarted by the 1986 space shuttle Challenger disaster, the late 1970s and the 1980s saw the consolidation and internationalization of China’s space effort.Footnote 33 Internal modernization was combined with an unforeseen opening up to the outside world. Cooperation projects began with France (1978), Japan (1978), West Germany (1979), the United States (1979), Brazil (1982), Italy (1983), Great Britain (1983) and the European Space Agency (1985). ‘While the indigenous manned programme has been postponed for the time being, it seems probable that a Chinese citizen will orbit the Earth before the end of the decade’, an observer stated in 1984.Footnote 34 During this second celebrification phase from 1985 through 1992, Qian was inaugurated as chairman of the China Association for Science and Technology (1987), received the American Willard F. Rockwell, Jr. Medal (1989) – an obscure award repeatedly hailed by Chinese biographers as the highest scientific honour – and was named State Scientist of Outstanding Contributions (1991) (see the white boxes in Figure 2).Footnote 35 These accolades resulted in an unprecedented number of media reports, with eighty-eight articles published in People’s Daily alone in 1988, the year preceding the Tiananmen Square massacre, which marked a pivotal moment in Qian’s celebrification.

Qian’s death on 31 October 2009 prompted a third attention peak, with numerous obituaries appearing in both the Chinese and the international press, as well as record-breaking numbers of mentions in Guangming Daily. As discussed below, this news coverage would only be topped two years later, in 2011, when Shanghai Jiaotong University opened the lavish museum exclusively devoted to his life and legacy.

Surprisingly, none of the three peaks was closely linked to China’s spaceflight achievements, in particular China’s otherwise widely celebrated ‘space firsts’ (see the red boxes in Figure 2). Neither the successful launch of Dongfeng 2 in June 1964, a medium-range missile powerful enough to carry a nuclear warhead, nor the positioning of the Dongfang Hong 1 satellite in April 1970, led to increased media publicity. Qian’s name was not mentioned in any of the reports. However, on the occasion of China’s greatest space success to date, the first human spaceflight undertaken by so-called taikonaut Yang Liwei in October 2003, Yang paid homage to the ailing Qian. In this pivotal Gagarin moment for China the baton was passed on to the next generation.Footnote 36 It was now up to the traveller, not the engineer, to take on the technocelebrity role.

Five facets of celebrification

Behind a large and ever-increasing corpus of writings of very different kinds, the ‘real’ Qian Xuesen has long become unidentifiable, to the degree of virtual disappearance. Interrogating Qian Xuesen himself is of little help. Unlike global rocket stars such as Arthur C. Clarke, Sigmund Jähn and Arnaldo Tamayo – deconstructed in other contributions to this special issue – and key space personas including Alexandre Ananoff, Gagarin and von Braun, Qian has left little, if any, substantial writing that could be labelled ‘autobiographical’.Footnote 37

Available ego-documents are limited to two short essays published upon his return and two brief self-reflections from the early 1990s.Footnote 38 Having had his movements conscribed within the borders of Los Angeles for five years, the early texts read as bitter indictments of the United States. They may have lent weight to his repatriation process and eventual Party membership admission in January 1959.Footnote 39 Qian showed little public self-reflection or any self-awareness of his increasingly exalted position in the PRC, not only for reasons of national security but also because of Qian’s firm will to privacy. Biographer Iris Chang noted this character trait as well: ‘To a striking degree few of his schoolmates ever remember having had a personal conversation with him’, she stated in 1995. Until his death, Qian refused to be interviewed, even though ‘a single conversation with him might have forever dispelled some of the shadows surrounding his life’, Chang lamented in Thread of the Silkworm.Footnote 40 This vehement, lifelong self-silence indicated an implicit form of compliance with the persona-building process. As celebrities and their publicists know, an aura of uncertainty and a veil of mystique are conducive to a person’s objectification, elevating them into a flexible and evocative icon.

Nonetheless, five components of a nascent Qian Xuesen myth emerge from the immense and ever-growing number of materials published since 1955, ranging from monographs, journal and newspaper articles to children’s literature, coffee-table books, graphic novels, television programmes, documentaries and feature films. Like sediments gradually superimposed upon one another, neither are these strata mutually exclusive, nor have they completely replaced one another. Rather, they surface at different moments, accumulating and accreting into a vast, impenetrable body of facets and factoids, quotes and anecdotes evoked time and again, albeit in different proportions and weightings. Here, these five facets serve as ideal types: first, a genius humiliated abroad and rescued by repatriation; second, the perfect family man; third, a humble people’s scientist learning from the people and serving the masses; fourth, a compliant functionary; and, fifth – a culmination of all other facets – the ‘father of spaceflight’ and ‘king of rocketry’; that is, an undisputed mastermind in the most challenging domain of modern technoscience.

Humiliated genius

Immediately after his homecoming, Qian was frequently depicted as a scientific genius wronged by American imperialism, an image that the new regime leveraged to entice more scientists abroad to return. Qian himself published two furious articles about his FBI case, one in Chinese, the other in English. ‘What a difference!’, he exhaled upon his return. ‘What brotherly warmth! No sensation-seeking reporter, no lurching F.B.I. man, no vulgar advertising poster! We breathed pure, clean, healthy air!’Footnote 41

This first facet gained particular momentum when Qian’s central role in engineering China’s future missile and space programme was publicly declared. After hearing him report on the Twelve-Year Science and Technology Plan in January 1957, renowned poet and president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Guo Moruo (1892–1978) composed a poem entitled ‘To Qian Xuesen’:

Looking up at the building, you see the moon above.

Pacific winds and waves are dangerous,

Breeze blows by the shore of the West Lake.

He has broken through the fence to return home,

Joining the grand plan and contributing his wisdom.

Twelve years henceforth,

Ride the rocket for interstellar roaming.Footnote 42

This poem described Qian’s journey back through peril and his subsequent contribution to the motherland’s scientific flourishing. The tumultuous homecoming through ‘pacific winds and waves’ culminated in the romanticized ‘interstellar roaming’ that the Twelve-Year Plan would realize.Footnote 43 Space exploration was the appeal even though Qian was leading a weapons programme. The poem personified China’s space ambitions through the face of a patriotic scientist whose hardships and ignominy mirrored the nation’s own. Time and again, the humiliated-genius facet was evoked to instigate anti-American sentiment, while synchronizing Qian’s life trajectory with national rejuvenation.

Family man

Even before the couple’s departure for China, Qian’s marriage to musician and opera singer Jiang Ying (1919–2012) was celebrated as a harmonious pairing of arts and science, the perfect union of the two cultures within a single family.Footnote 44 Beginning in 1956, articles in popular journals featured photographs of Qian with his wife and two children taken at their apartment in Beijing. Returning to China allowed Jiang to resume her musical career. As one story suggested, while in Pasadena Jiang had had to put aside her own professional advancement, but now the couple could finally act on an equal footing.Footnote 45

Portraying Qian as the perfect family man resonated with the Mao era’s (1949–76) promotion of gender equality and women’s liberation. However, the more pronounced Qian’s space-father persona became during the post-socialist period, the more the formerly egalitarian family-man image reverted to a patriarchal version, relegating Jiang again to a supportive domestic role.Footnote 46 In 1991 Qian maintained that his scientific achievements were ‘nurtured in music and the arts’, thanks to his wife. Qian’s integral contribution to space science was thus credited to the couple’s gendered collaboration, unsymmetrical as it was.Footnote 47

People’s scientist

Third, to make Qian a cornerstone of the new China, his persona had to be transformed from a Westernized bourgeois intellectual to that of a genuine people’s scientist. His humble image entailed a new self-denomination as ‘technological and scientific worker’, dressed either in Chinese military uniform or in the so-called Mao suit.Footnote 48 His willingness to work with the public was evident in Qian's commitment to science popularization, as he published dozens of articles on mechanics, aerodynamics and cybernetics between 1955 and 1990.Footnote 49

Accordingly, Qian is known to have received thousands of letters from the public seeking advice on a wide range of subjects.Footnote 50 His correspondence with Nanjing factory worker Yu Qiaocheng regarding the possibility of constructing a perpetual-motion machine, serialized in 1965 in Guangming Daily, serves as an exemplary demonstration of the performative nature of this facet. Initially dismissing its feasibility due to the law of conservation of energy, reader dissatisfaction caused Qian to modify his position two months later. While acknowledging the potential for socialist societies to create miracles and achieve feats unattainable in a capitalist system, he strategically reiterated ‘Chairman Mao’s instructions to be realistic and respect the objective laws’, which asserted that no machine could work indefinitely without consuming energy.Footnote 51 What Qian practised here would become a recurring ritual during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76): quoting Mao as a means to reaffirm one’s own authority.

Compliant functionary

Between 1955 and 1976, Qian and Mao are said to have met at least six times. Four photographs of these encounters are known.Footnote 52 Often cited as a testament to Qian’s political shrewdness and a talisman protecting him from tumultuous political campaigns, these photographs portrayed the scientist as a compliant functionary and loyal patriot, smiling and attentively listening to the chairman. In times of factional politics, Qian’s name was invoked to provide scientific backing for the CCP’s policies and to mediate within the capricious state–science relationship.

Qian’s photographs with Mao inspired further artworks and literary narratives, portraying their prolonged rapport to justify and sustain the CCP’s legitimacy. An oil painting, Loving Care, painted one year after Mao’s death in 1976, restaged one of those meetings (Figure 3).Footnote 53 The painting accentuated Mao’s unwavering support of scientific research and protection of scientists. While Qian’s image was deployed to uphold Mao’s stature well into the late 1970s, it also perpetuated Qian as a red expert loyal to the Party and a model to be emulated by other scientists. To the chagrin of his colleagues, Qian was one of the few scientists exempt from persecution during the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 54

Figure 3. Qian Xuesen (right) drinking tea with Chairman Mao Zedong (1893–1976, left) and geologist Li Siguang (1889–1971, centre) in Zhongnanhai on 6 February 1964. Sun Wenchao and Zhang Defu, Qinqie de guanhuai (Loving Care), n.p.: Renmin Meishu Chubanshe, March 1978; Guangming Daily, 18 September 1977, p. 3.

Father of spaceflight

Ultimately, these four facets culminated in Qian becoming the ‘father of Chinese spaceflight’. This equation is of much more recent origin than is conventionally assumed and must be read as a direct reaction to the Tiananmen massacre. The government’s crackdown on the pro-democracy student movement created an unprecedented chasm in its relationship with reform-minded intellectuals and undermined the PRC’s legitimacy. Building up an ‘academically prestigious and politically dependable scientist’ as national hero and role model promised to restore political stability.Footnote 55

Archival research undertaken for this article suggests that there may have been a deliberate decision to emulate the international ‘father-of’ trope, with Qian ideally positioned to fit that model by the Chinese state. As Qian’s expertise in rocket technology was originally imported from abroad before being appropriated domestically, so was the father title. After a complex process of terminological canonization and conceptual demilitarization, not dissimilar to Soviet and American attempts to hide the military significance of rocketry behind the veil of peaceful space exploration and science, the trope came to be widely used during the 1990s. While a Chinese newspaper article referred to the ‘father of Chinese missiles’ as early as 1983 – referencing a United Press International profile by journalist Robert Crabbe – the first Chinese monograph featuring the ‘father’ title appeared in 1995.Footnote 56 In October 1989, a People’s Daily editorial on the international political situation after the ‘counter-revolutionary riot’ hailed Qian ‘father of Chinese missiles’.Footnote 57 Within those twelve years, from 1983 to 1995, the ‘father of Chinese missiles’ (daodan zhi fu) transformed, first, into the ‘father of Chinese rocketry’ (huojian zhi fu) and then ‘father of Chinese spaceflight’ (hangtian zhi fu).Footnote 58 Early in this process, Chinese-language publications juxtaposed Qian with other global space personas and internationally celebrated ‘father’ figures such as Wernher von Braun (1984), Robert Goddard (1985) and Konstantin Tsiolkovskii (1994).Footnote 59

In European and American newspapers, the terminological canonization set in earlier but proceeded in a similar manner, moving from boy to man to father, and from missiles and rocketry to outer space. The titles assigned to Qian might have been inspired by von Braun, to whom Time magazine had dedicated a much-acclaimed cover story in 1958, christening him ‘missileman’.Footnote 60 First referred to as ‘one of the most important, most dangerous men in the world’ (1960), ‘China’s no. 1 A-boy’ (1966), ‘A-missile man’ (1966), ‘Peking’s rocket maker’ (1970), ‘Vater der chinesischen Fernraketen’ (1970) and ‘China’s missiles chief’ (1970), Qian gradually metamorphosed into ‘China’s Werner [sic] von Braun’ (1969), a ‘top rocket expert’ (1971) and, eventually, the ‘father of Chinese missiles’ (1980).Footnote 61 Accordingly, Chang’s 1995 biography was originally to be titled ‘Tsien Hsue-Shen: father of the Chinese missile’, with a different version having ‘Father of the Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile’ as its subtitle.Footnote 62

Granting Qian paternal honours was a strategic and apparently intentional political move. ‘The process by which Qian was chosen is unknown’, historian Ning Wang has speculated about the CCP’s quest to identify and build up a Party scientist after the 1989 caesura, ‘but it seems that [Qian] was finally agreed upon as the best candidate’.Footnote 63 An as yet unpublished, unremarked document buried amongst Iris Chang’s papers confirms Wang’s instinct. ‘Why, then, is there such a myth around him?’ Hua Di, a former colleague and high-ranking official who had left China after 1989, mused:

You need to have a symbol. This comes from abroad, I think. Sakarov was the father of the Russian space program. Teller was the father of the H bomb. But who is the father of the Chinese space program? No one has that kind of high reputation except Tsien.Footnote 64

While Hua’s assessment does not prove that Qian’s celebrification was as centrally planned and systematically executed as it appears in hindsight, it does suggest that the Party was cognizant of the degree to which it would benefit from crowning Qian the ‘father of Chinese spaceflight’. Qian himself disapproved of the bestowing of any paternal honours just as much as he continued to reject his ongoing biographization. ‘It is unscientific to call me the “father of missiles”,’ Qian objected time and again, ‘because missiles and satellites are “large scientific projects” and are made by the concerted efforts of millions of people’.Footnote 65

Qian Xuesen fever

With the exception of Yuri Gagarin and the persistent cult around him, no other global space persona, including Wernher von Braun and Sergei Korolev, has been subject to such persistent star making and continuous hero worship as Qian Xuesen.Footnote 66 Coinciding with the father-figure trope’s increased popularity in the 1990s, numerous ‘unofficial’ – that is, unauthorized – and frequently derivative biographies began to appear on the Chinese book market.Footnote 67

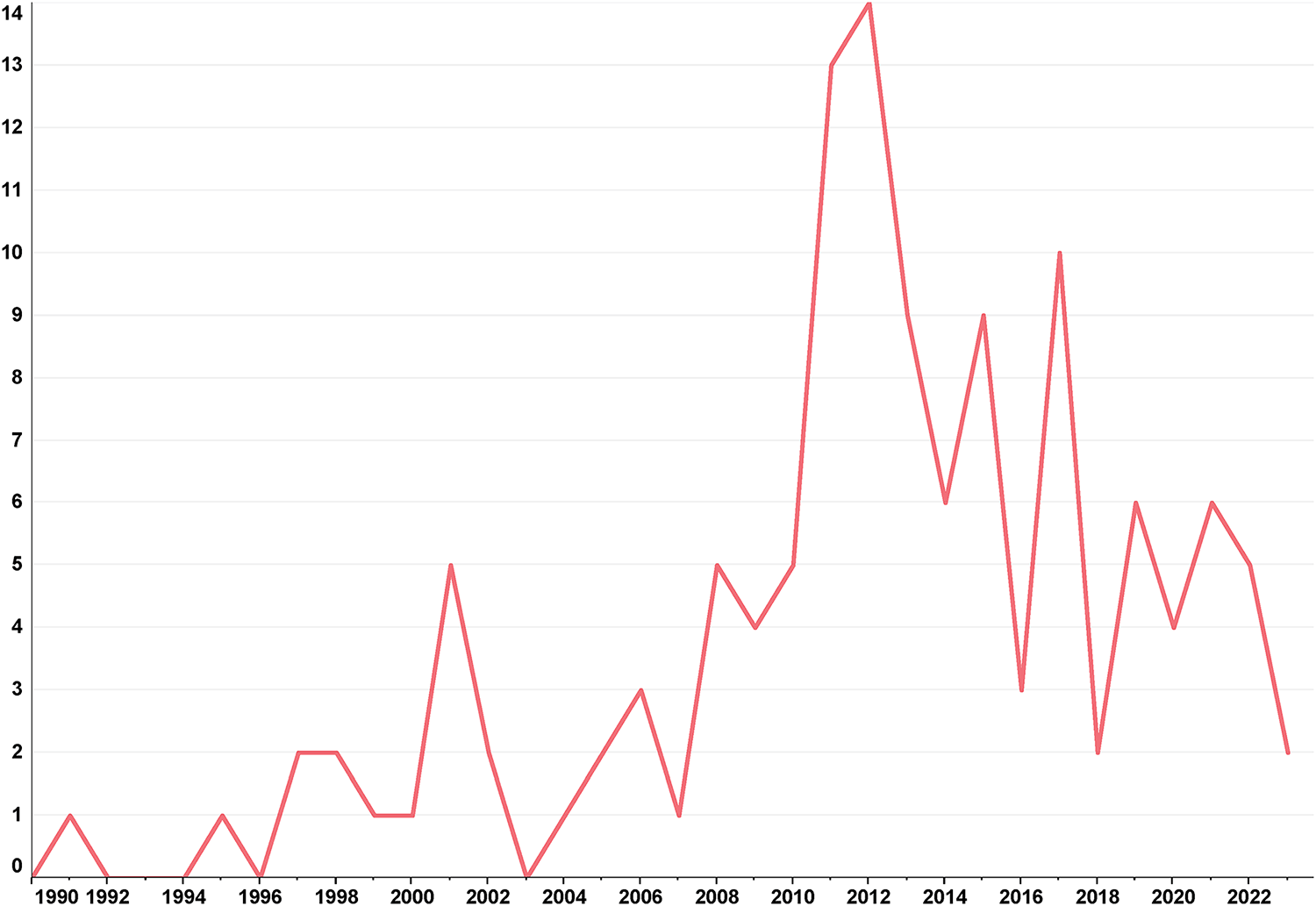

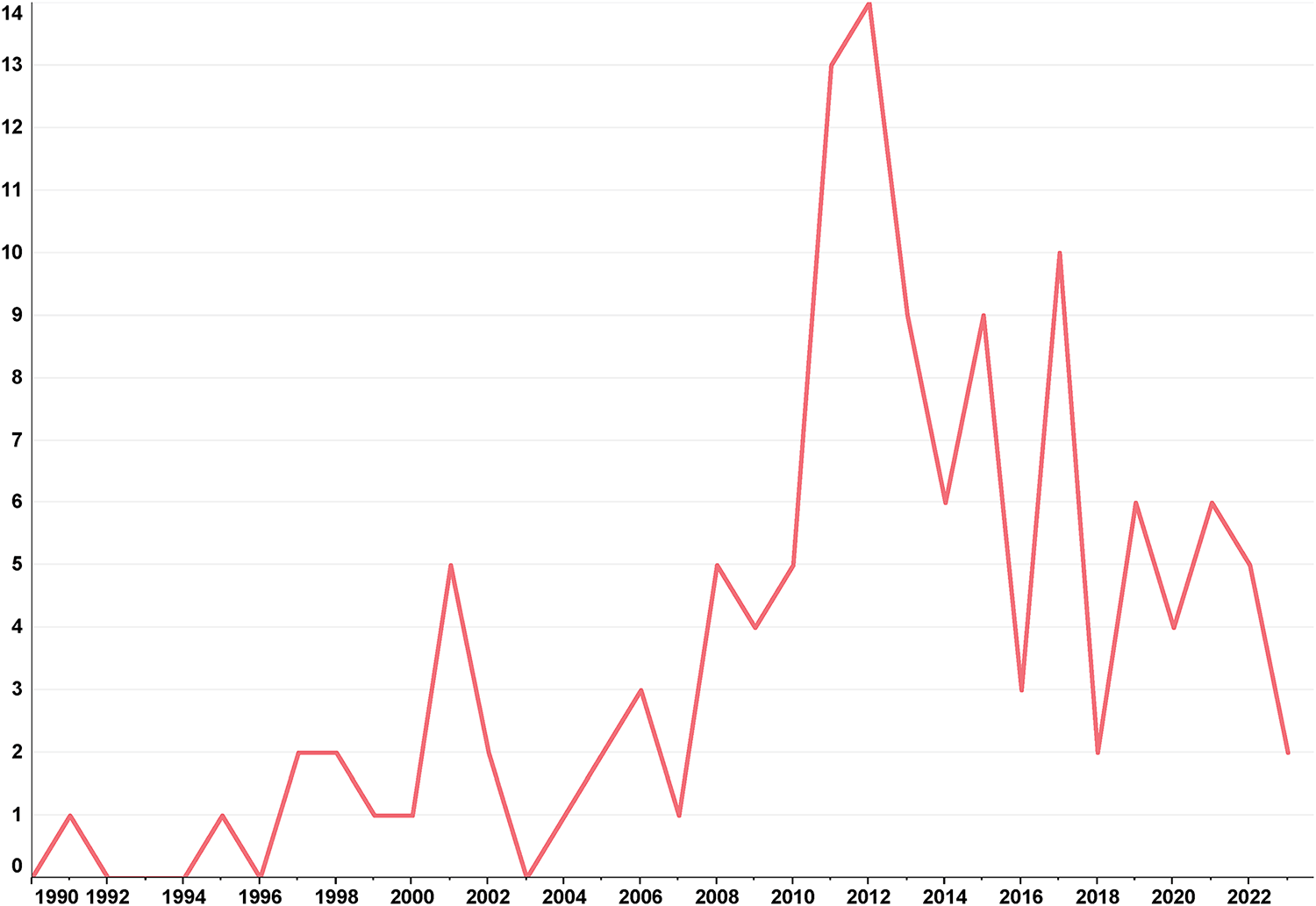

Over 130 monographs on Qian Xuesen were published between 1990 and 2023 (Figure 4). The 2010–13 peak reflects Qian’s death in 2009 and the hundredth anniversary of his birth, widely celebrated in 2011. Unlike the official biographies authored by Qian’s former secretaries or compiled by researchers at the Qian Xuesen Museum, most unofficial biographies were written by little-known journalists, amateur historians and devotees, aiming at a domestic audience including children.Footnote 68 For this ever-growing body of literature Wang has coined the evocative term ‘Qian Xuesen fever’.Footnote 69 As Figure 4 demonstrates, the number of unauthorized biographies more than doubled during the third decade of its existence, repeatedly reaching spikes in 2011 (thirteen volumes), 2012 (fourteen) and 2017 (ten). Even if it may have abated somewhat in recent years, the Qian Xuesen fever persists.

Figure 4. The number of ‘unofficial’ biographies of Qian Xuesen published between 1990 and 2023. Graph by Raven M. Davis, Georgia Institute of Technology.

A textual analysis yields three interrelated paradoxes present in this vast body of literature: first, official versus unofficial authorship; second, Marxist versus commercial imperatives; and third, socialist versus post-socialist values:

Official versus unofficial authorship

Both official and unofficial cultural productions have driven the biographical fever, with state-sponsored efforts initiating and fuelling Qian’s celebrification. Amateur authors, commercial publishers and Chinese netizens have appropriated, expanded and perpetuated the official narrative. Although unofficial biographies have rarely deviated from canonized state parlance, their overt mythologization of Qian as deus ex machina has elevated him above other scientists, thus implicitly challenging the collectivist spirit extolled by the CCP while simultaneously fostering a personality cult.

Marxist versus commercial imperatives

Maoist exemplarity where the hero was impeccably ‘lofty, grand, and complete’ coexisted with a market-driven appeal to the reading public’s appetite for past national secrets and the private lives of celebrities. Any critique was to be avoided, and anything controversial must be cleared, as demonstrated by the reticence about Qian’s support of the Great Leap Forward (1958–62) and the qigong fever in the 1980s.Footnote 70 Meanwhile, with the help of hitherto undisclosed anecdotes, successive biographies claimed to account for the ‘real Qian Xuesen’ and, through him, to lay bare the ‘unknown history of China’s space program’. Intriguingly, the purported ‘first use’ of original materials often proved highly derivative. Lacking unmediated access to new research materials and without the possibility of conducting additional interviews, biographers fell back on copying details and recycling anecdotes from each other, retransmitting mistakes from previous works without acknowledging their sources.Footnote 71

A single anecdote must suffice to illustrate how the biographical process naturalized Qian’s status as ‘father’ of the space programme. Originating in an early 1990s memoir by Qian’s classmate Zhang Wei, a widely circulated story claimed that little Qian could make paper aeroplanes that flew farther than those of his classmates.Footnote 72 The first Chinese unofficial biography, Father of China’s Space Program Qian Xuesen (1995), dramatized the episode that, unwilling to be defeated, Qian’s classmates kept asking for another round of the competition but never surpassed him. ‘It amazed his teachers and friends that at such a young age, he already knew the aerodynamics behind the game’, the narrator referred to the research field Qian would join later. By 2013, little Qian had evolved from a dexterous technician to an aerodynamic theoretician who could explain the mechanics of aviation to his classmates.Footnote 73 Through continuous reiteration, the story has verged on an oracular presage of the schoolboy’s growth into the father of China’s space programme.

Socialist versus post-socialist values

Finally, biographers had to reconcile idolizing Qian in Maoist historiography with narrating ‘the nation’s collective maturation from naïve political passions to sound economic sensibility’.Footnote 74 After 1978, a new ideology of rationalism and developmentalism replaced class struggle, increasingly emboldening biographers to celebrate Qian’s international education, pragmatic planning and aversion to ideological dogmatism. A blurb for one of these unofficial biographies compressed all five facets into four brief sentences:

In his heart, his country is more important while his family is less, science is the most valuable and fame is the least. Five years on the road to his homeland, ten years for two bombs. He was a pioneer in the creation of the motherland’s space programme, forging his wisdom into a ladder and leaving it to later climbers. He is a treasure of knowledge, a banner of science, and a model of Chinese intellectuals.Footnote 75

Over time, the five facets, while remaining the building blocks of Qian’s persona, have mutated and cross-pollinated to accommodate reform-era values. The origins of Qian’s patriotism were stripped of any ideological connotations in order to be more visceral and relatable. Biographies reframed the exclusion suffered by the ‘humiliated genius’ in the United States as stemming from his Chinese descent rather than any alleged communism. Unverifiable incidents of reported racism were embellished over time, both to incite anti-American sentiment and to deflect attention from taboo topics. In one instance, biographers extolled Qian’s decision not to accept the Rockwell Medal in person in 1989 as evidence of his allegiance to the CCP, and removed any traces of Sino-US tensions in the post-Tiananmen period.Footnote 76 Qian’s departure was recontextualized as an act of patriotism catalysed by the experience of discrimination.

Refashioning Qian Xuesen as a reform-era Party hero de-Maoized China’s space and missile programmes. Unofficial biographies accentuated a sense of truth-revelation revolving around China’s space effort, portraying Qian as secretly objecting to ultra-leftist policies in his conversations with the CCP’s top echelon. It was said, for instance, that Qian’s visionary concerns about over-reliance on Soviet space technology before the 1960 Sino-Soviet split received applause from senior general Chen Geng. Premier Zhou Enlai even encouraged Qian to disregard the ‘mass line’ – a fundamental Maoist precept asserting that power originates from the masses – to form an elite circle of missile experts in the making of the 1956 Twelve-Year Plan.Footnote 77 While these vignettes may have incurred political accusations in their own time, they were safe enough to be declassified as they endorsed practicality over ideology, development over class struggle. Thus the missile and space programmes were successfully divorced from the stale revolutionary discourse. The space effort became a vessel of national pride, achieved despite, not because of, the overt influence of Maoism. With the opening up of China after 1978, Qian’s ambiguous encounter with the West only burnished his credentials for the role of science hero. For a nation undergoing rapid transformation, anointing Qian meant neither ignoring nor capitulating to the ‘imperialist’ challenge.

Ascension and afterlife

When Qian died on 31 October 2009, short of his ninety-eighth birthday, some 10,000 mourners, including CCP leaders President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao and former president Jiang Zemin, were reported to have attended the lavish funeral held at Beijing’s Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery.Footnote 78 Qian’s decades-long celebrification did not conclude with his death. Rather, it inaugurated a third phase which continues to this day. If the post-1989 phase saw the building up of his renown as the ‘father of Chinese spaceflight’ as a means to counter the post-Tiananmen crisis, it was after Qian’s hundredth birthday in 2011 that the poster child of Chinese astroculture morphed irrevocably into the ubiquitous science superstar he is in today’s China.

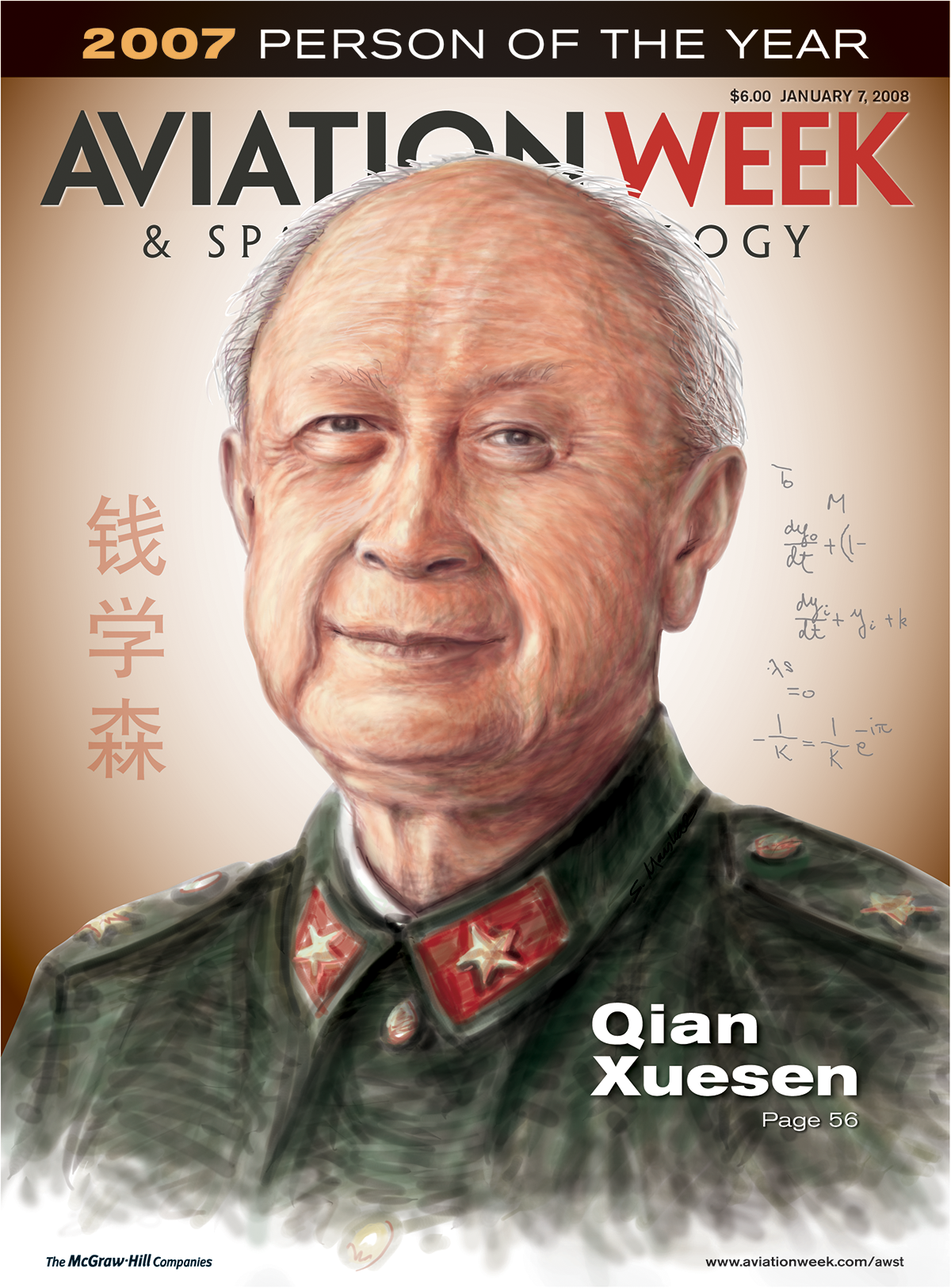

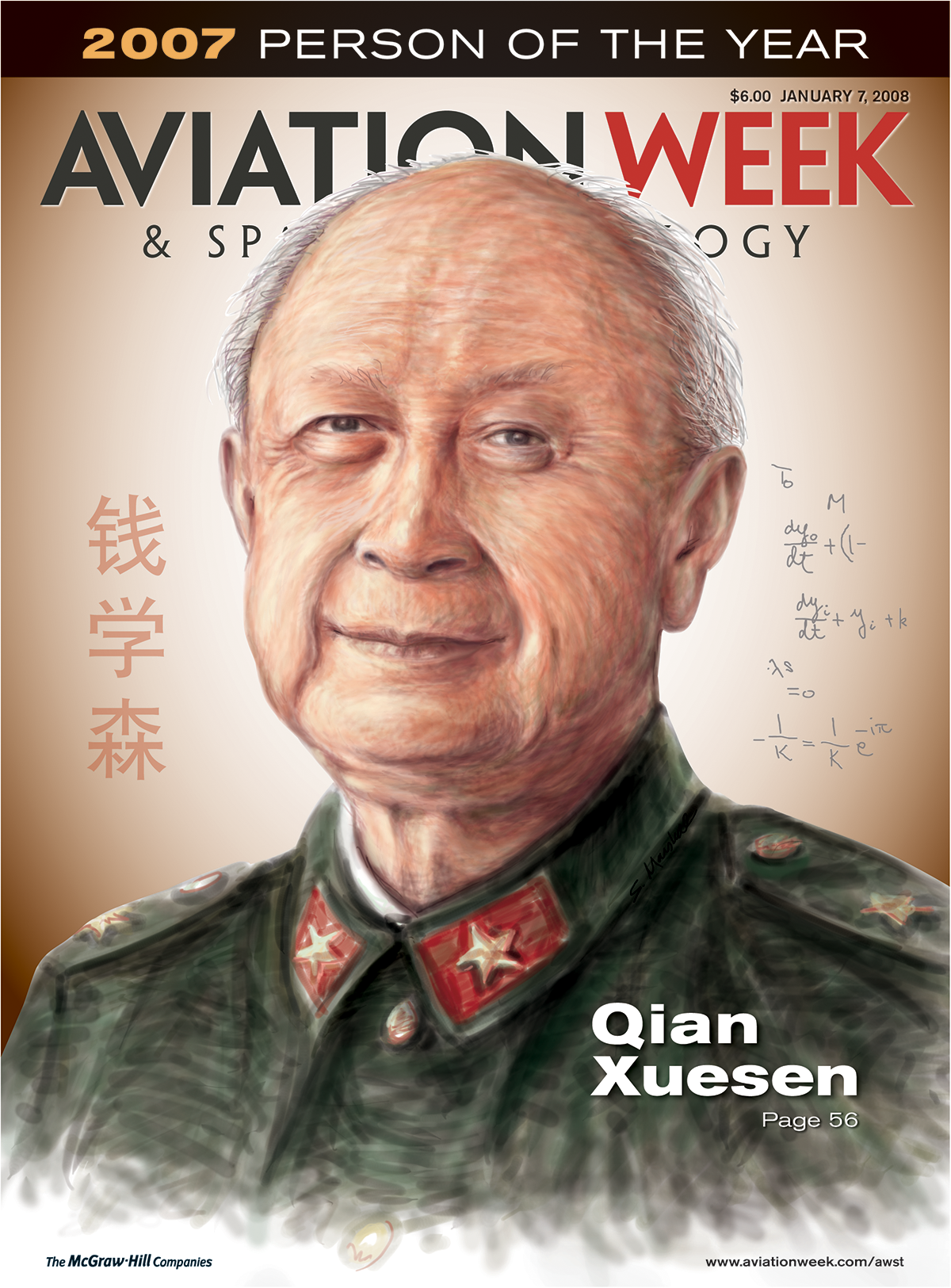

Together with a growing realization of China’s status as an emerging world power, an international audience finally began to take notice of Qian, albeit to a limited degree. Iris Chang had opened her 1995 biography by stressing the discrepancy between the domestic and the international Qian.Footnote 79 When Caltech’s alumni magazine published a reminiscence by former friend and collaborator Frank E. Marble (1918–2014), a classmate expressed surprise at the long-standing silence: ‘I have often wondered what happened to him after deportation’, he wrote in 2002, ‘but except for brief mentions in reports on Chinese missile development, there has been nothing in the press I read’.Footnote 80 A year prior to Qian’s death, Aviation Week & Space Technology put a stylized portrait of the ninety-six-year-old on its cover and declared Qian ‘Person of the Year’ (Figure 5). ‘Not well known in the West, he is the father of China’s space efforts’, the editors introduced their cover model, attributing China’s unforeseen ascent into space directly to ‘this very old man’ and underscoring the fact that Qian’s expertise was a major loss for the United States to China.Footnote 81

Figure 5. In January 2008, Aviation Week & Space Technology declared Qian Xuesen ‘Person of the Year’. Cover illustration by Scott Marshall. Courtesy of Aviation Week & Space Technology.

Qian’s international comeback appeared akin to a lost satellite suddenly re-entering Earth’s orbit. China’s first human spaceflight in October 2003 and Qian’s death six years later led to an unprecedented, yet short-lived, rise in international recognition (Figure 2 above). Whether hailing Qian as ‘Vater der Raketentechnik und Raumfahrt’, ‘“padre” del programa espacial chino’ or ‘père des technologies aérospatiales chinoises’, two thirds of the three dozen obituaries published in English, French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish newspapers featured the father-figure trope.Footnote 82 ‘And then he became the father of rocket technology and space travel – in China’, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung could not conceal its astonishment, whereas the Daily Telegraph correlated Qian’s technological paternity with his involvement in the Chinese military–industrial complex: ‘Qian Xuesen … was the father of China’s missile and space programmes, transforming the country from a primitive technological backwater to a nuclear power’, it stated.Footnote 83 One of the few Western newspapers to point to the multifacetedness of Qian’s persona and offer a more nuanced assessment of his bipartite life was the Financial Times. ‘Qian Xuesen … was a unique figure in the history of the world’s missile and nuclear arsenals, with a career that straddled the secretive military establishments of the capitalist west and his communist homeland’, their obituary noted:

Qian remained a revered and iconic figure in the official media in China, lavishly praised for his loyalty to ‘the motherland’. But excluded from the respectful Chinese commentary after his death … was how he had been used by Mao Zedong and his henchmen in their brutal political campaigns.Footnote 84

Otherwise buying into the celebratory fatherhood narrative, these obituaries acquainted an international audience with Qian at a time when China’s ambitions in space became increasingly hard to ignore.

Yet the difference between Qian’s domestic and international recognition remains stark. To account for the Chinese state’s gigantic investment in spaceflight technology since the 1950s, political scientist Michael Sheehan has juxtaposed national with international explanations. According to Sheehan, the Chinese space programme has been driven by domestic considerations, particularly with a view to enhancing the government’s prestige, while its self-positioning among great-power peers is of far lesser significance.Footnote 85 The findings presented here support this approach. Qian serves to personalize and humanize the Chinese space effort to a predominantly domestic audience, and few attempts at internationalization have been made.

Domestically, Qian’s status is assured. The third boom phase that set in with his death encompassed not only further unofficial biographies, comic books and television documentaries, but also the opening of the aforementioned Qian Xuesen Library and Museum in 2011.Footnote 86 Designed by He Jingtang, the architect of the Chinese Pavilion at the Shanghai 2010 EXPO, and situated adjacent to Jiaotong University’s idyllic campus, the museum forms part of one of China’s most revered universities of technology.Footnote 87 The exterior of the eight-thousand-square-metre large building of reddish Gobi rock has a three-dimensional silhouette emerging from its facade. Dedicated exclusively to Qian’s life, work and impact, the museum displays personal belongings, photographs, letters and artefacts alongside especially created videos, dioramas and models. Anchoring the entrance hall is an original Dongfeng 2 missile, twenty-one metres long, standing next to a large bronze bust. Not unlike the five facets identified above, four exhibition sections spread over two floors recount his biography in four different iterations: Qian as the ‘Founder of China’s aerospace venture’, as a ‘Pioneer in the frontier of science and technology’ and as a ‘Scientist of the people’, in addition to ‘Key to success of a strategic scientist’.Footnote 88 While the first two sections focus on Qian’s contribution to spaceflight and the sciences, the third concentrates on Qian as a public intellectual. The fourth aims to motivate young visitors to emulate his achievements, a clear nod to the ‘Qian Xuesen question’ discussed below. As historian John Krige has observed, ‘knowledge acquired abroad is denationalized; while knowledge developed in China is indigenized.’Footnote 89 More striking than any other Qian paraphernalia flooding present-day Chinese astroculture, the presence of such a well-endowed shrine in the heart of Shanghai testifies to the political centrality assigned to Qian.

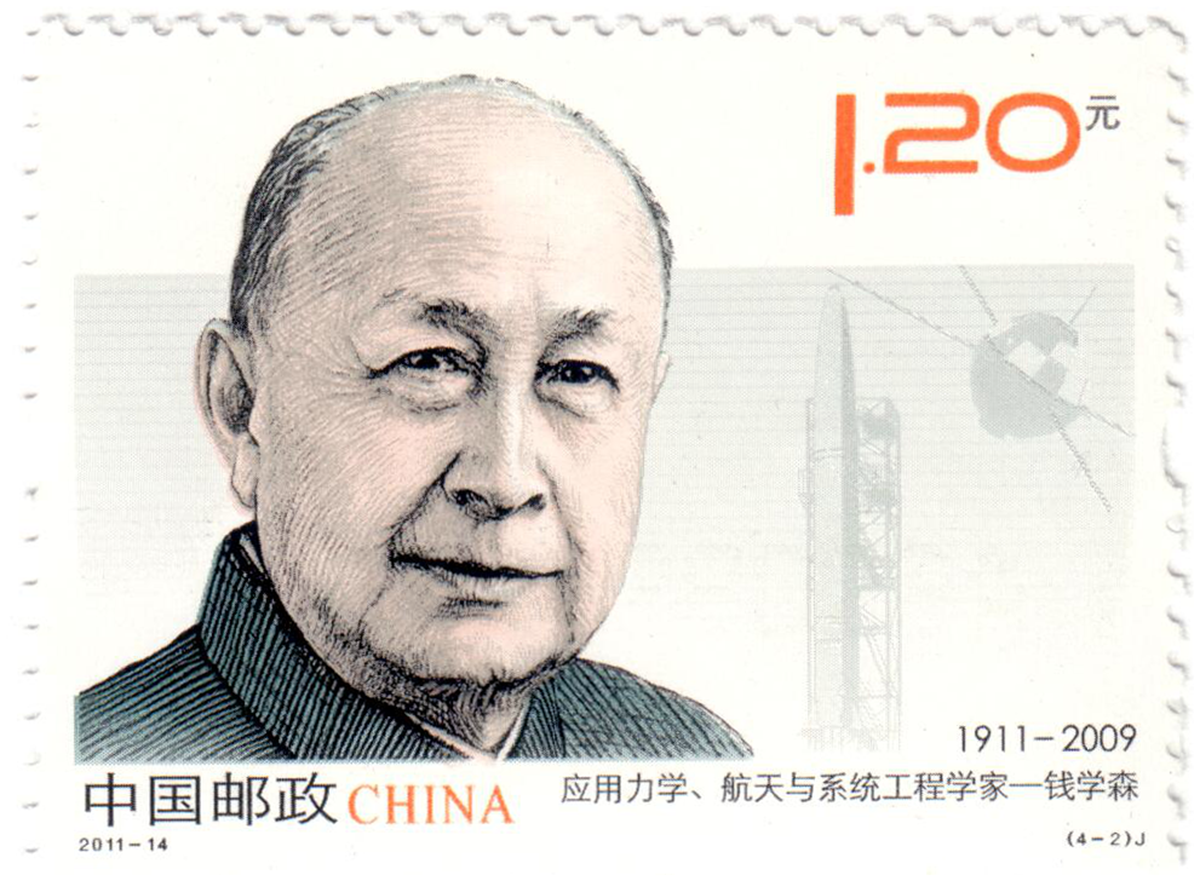

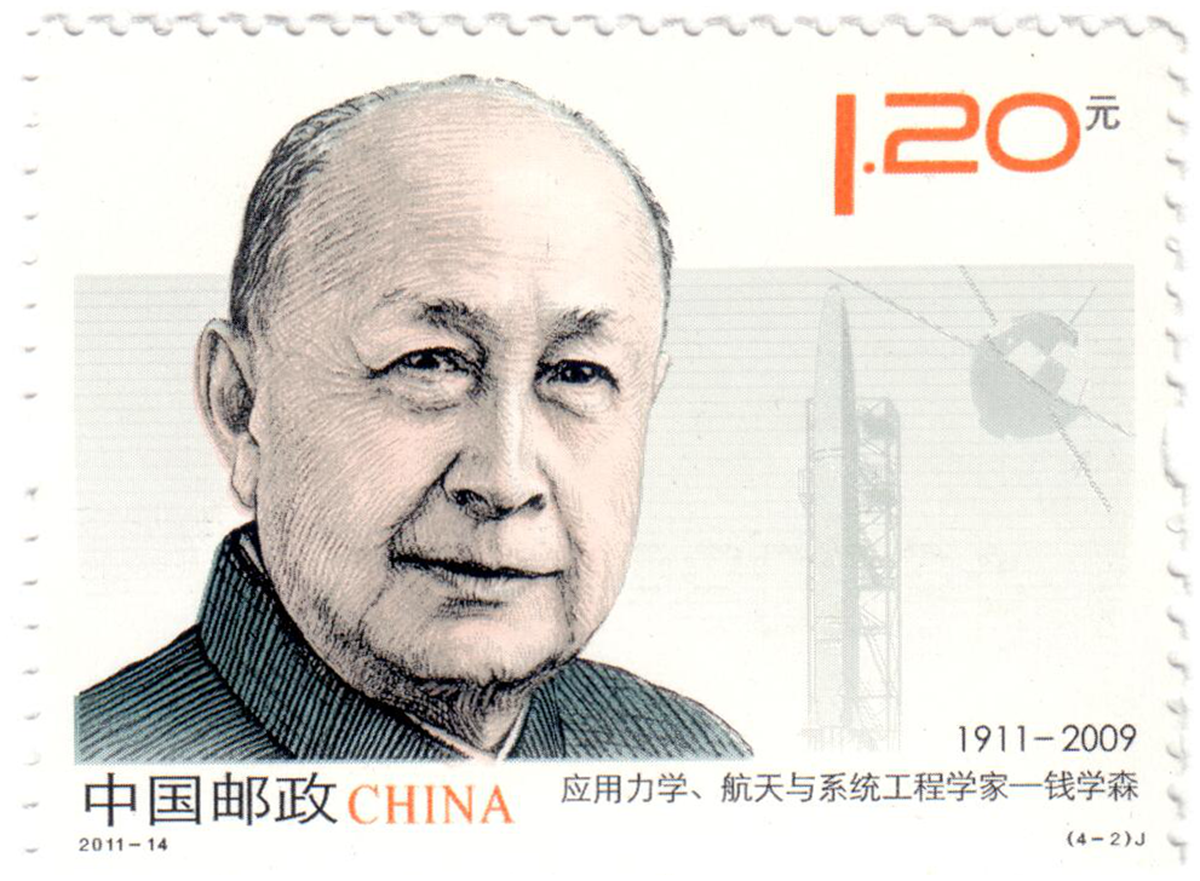

Qian’s posthumous musealization did not stop there. To coincide with the museum opening, China Post released a commemorative stamp (Figure 6). While the caption identified him as a ‘scientist in applied mechanics, aerospace and systems engineering’, the stamp’s layout speaks a different language. His lightly coloured portrait looms large, expressing paternal trustworthiness and patriotic pride, yet it is the two technical artefacts added to the background – the emblem of a Changzheng 3 rocket (1984) and the Dongfang Hong 1 satellite (1970), two of China’s biggest space achievements – that signalled the true vocation of the portrayed. Compared with the 1990 poster (Figure 1 above), Qian’s disproportionately large portrait against the blurred background articulated a continuously amplified symbol overseeing and overshadowing the space effort project.

Figure 6. On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Qian Xuesen’s birthday in December 2011, China Post issued a commemorative stamp as part of its Scientists in Modern China set. Authors’ collection.

Just as the museum opened and the stamp was issued, dramatic representations were burgeoning. A sentimental 2012 biopic Hsue-shen Tsien cloaked the party-state-sanctioned patriotic narrative with commercial appeal and Hollywood-style dramatization, only to receive lukewarm reviews.Footnote 90 The film concludes with Qian’s first television appearance in 1956. Documentary footage is interwoven with the fictionalized storyline, presenting a retrospective assessment of Qian’s achievements. Through strategic collapse of the persona and the person, the film self-referentially interprets the ‘authentic’ Qian Xuesen as a product of the media.

Beyond this array of cultural productions – a hagiographic museum, a commemorative stamp, a wannabe blockbuster – all construing, celebrating and commemorating a space persona in infinite variations of the same, Qian’s most sustained legacy may, finally, lie in the so-called Qian Xuesen question. Originally raised by Qian himself at the onset of the second celebrification phase in 1992, taken up by Premier Wen Jiabao in 2005 and resurfacing again after Qian's death, the question invokes a conscious self-critique, asking why Chinese universities have not produced a single ‘world-class’ scholar since 1949.Footnote 91 As such, the Qian Xuesen question constitutes the counterpart to what American observers termed ‘the Chinese puzzle’, wondering how the PRC managed to develop nuclear capability and become operational within just a few years.Footnote 92 Both technopolitical conundrums centre on different aspects of Qian’s persona. Widely applied to criticize centralized control and the extensive bureaucracy of Chinese universities, the Qian Xuesen question remains a pillar of present-day higher-education debates.

Deconstructing the Chinese space patriarch

It is difficult to overestimate Qian Xuesen’s presence, popularity and prominence in today’s China. As this article has shown, his metamorphosis from a US-based rocket engineer to China’s face of space underwent three consecutive phases. News reporting intensified after Qian's return in the autumn of 1955, yet remained limited over the course of the next three decades. It intensified in the second half of the 1980s and the early 1990s, in particular after Tiananmen Square. Building up a rocket star provided a means through which the Chinese state could counter an unprecedented crisis of political legitimacy and establish a hitherto missing link between the state, its ever-expanding military-run space programme and the public. Qian’s death in 2009 heralded the third phase of celebrification, exemplified by the opening of the eponymous museum in 2011.

Qian’s ubiquity continues to grow. In late 2021, Qian was one of the very few non-politicians mentioned by name in the official Concise History of the Communist Party of China, assigning him his place in the PRC’s glorious past. ‘[T]hese achievements [two bombs and one satellite] brought great pride to the Chinese nation. A large number of scientists such as Qian Xuesen … tied their personal ideals to the fate of the motherland and their personal aspirations to the revitalization of the nation’, it stated.Footnote 93 For a space persona to be sanctioned by the state and featured in such authorized annals is unusual enough; with the exception of Gagarin, no other rocket star has ever received such regiminal honours. The conflation of Qian’s persona and China’s space programme has come full circle. As the iconic figurehead of Chinese astroculture, the ‘father of spaceflight’ and ‘king of rocketry’ constitutes an essential building block of the China Dream, as central to the country’s highly ambitious space programme as it is to the edifice of society envisioned by its leadership.

Ironically, however, while the celebrification of Qian Xuesen, historically accurate or not, was fundamentally grounded in an equation of fatherhood and spaceflight, the exact nature of Qian’s own contribution to the gradual crafting of his persona vis-à-vis the development of rocket technology has been lost, if it ever existed. Other than ceaselessly hailing him for ‘embarking on his “missile journey” for the new China’, Qian’s countless biographers have surprisingly little to offer on how he effectively opened up outer space, both real and imagined, to China.Footnote 94 Conversely, the Qian–space synecdoche – mentioning Qian inevitably evokes his paternal title and, in turn, the very space effort he is said to have launched and nurtured – is so firmly established and unquestioningly accepted that the details of any merit that might have earned him this title disappear in the distant past. Qian is the father of Chinese spaceflight; how precisely he fathered what is irrelevant. From such a perspective, the carefully crafted and meticulously maintained persona of Qian Xuesen and outer space parallel one another. Both constitute empty signifiers: powerful, protean and alluring, yet endlessly polymorphous and multivalent. As the proverbial father figure and figurehead of the Chinese space programme, Qian’s persona is as politically effective as it is elusive. Potent and captivating while morphing and ever-changing, it incorporates a plethora of meanings. It is perhaps only fitting that the rocket star and science hero that the Chinese party state required, produced and nurtured should prove all-encompassing, yet ontologically void. Taikong, the Chinese term for outer space, literally means: ‘too empty’.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Maximilian Arrouas, Martin J. Collins, Raven Davis, Ingrid He, Sijia Huang, Anna Kathryn Kendrick, John Krige, Xiaoyue Luo, Scott Marshall, Michèle Matetschk-Delhaes, Michael Neufeld, Florian Preiß, Wenjia Qiu, Amanda Rees, Zuoyue Wang, Kai Zhang and all members of the Global Astroculture Research Group, in particular Haitian Ma and Tilmann Siebeneichner, in addition to the anonymous reviewers. We are also grateful to the archivists at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and the Department of Special Research Collections at UC Santa Barbara. Qian Xuesen’s papers are held by the Qian Xuesen Library and Museum, Jiaotong University, Shanghai. Despite repeated visits and attempts made over a prolonged period of time we were, alas, not granted access.