Mental disorders of women during the postnatal period are a major public health problem that can significantly impact on the health of the whole family.Reference Almond 1 – Reference Wisner, Chambers and Sit 3 There are consistent reports of an increase in hospital admissions for mental disorders in the first year after birth.Reference Kendell, Chalmers and Platz 4 – Reference Xu, Austin, Reilly, Hilder and Sullivan 7 A recent prospective cohort study in Melbourne (n=1507 nulliparous women) found that 16.1% of women reported depressive symptoms during the first 12 months post-partum.Reference Woolhouse, Gartland, Perlen, Donath and Brown 8 In New South Wales (NSW), a population-based study found that the hospital admission rates for psychiatric disorders in the first year after birth increased significantly between 2001 and 2010 with a more marked increase from 2005 (1.16% in 2001, 2.28% in 2010).Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 However, the studies on women during pregnancy is less consistent.Reference Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant and Hasin 5 , Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Mendelson and Pedersen 10 , Reference Ibanez, Blondel, Prunet, Kaminski and Saurel-Cubizolles 11 The studies based on health service data showed a decrease in hospital admission for mental disorders during pregnancy.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Xu, Austin, Reilly, Hilder and Sullivan 7 The studies based on surveys reported an increaseReference Ibanez, Blondel, Prunet, Kaminski and Saurel-Cubizolles 11 , Reference Milgrom, Gemmill, Bilszta, Hayes, Barnett and Brooks 12 or a decreaseReference Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant and Hasin 5 in women's mental disorders during pregnancy.

Compared with maternal depression, much less attention has been paid to men's mental disorders in the perinatal period.Reference Goodman 13 Studies of fathers’ hospital admissions for mental disorders during the perinatal period have shown varying findings.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Garfield, Duncan, Rutsohn, McDade, Adam and Coley 14 A systematic review showed that the rate of diagnosed depression in new fathers at 6 weeks post-partum was around 2–5%.Reference Wee, Skouteris, Pier, Richardson and Milgrom 15 An integrative review from community samples showed that the incidence of paternal depression ranged from 1.2 to 25.5% during the first post-partum year.Reference Goodman 13 The range was very wide because of differences in the measuring tools used, cut-off point, time of measurement and study population. A study in England (n=7018 partners of women in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood) showed that the prevalence of paternal depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Scores >12) was 3.5% at 18 weeks gestation and 3.3% at 8 weeks following the birth.Reference Deater-Deckard, Pickering, Dunn and Golding 16 A cohort study based on Danish population data (630 373 women and 547 431 men) showed that new fathers had a decreased risk of hospital admission for mental disorders in the first year after birth compared with non-fathers.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6

There are relatively few studies focusing on the association between paternal and maternal mental disorders.Reference Pinheiro, Magalhaes, Horta, Pinheiro, da Silva and Pinto 17 A study based on community data in England found that men's depressive symptoms were correlated with their partners’ depressive symptoms before and after birth.Reference Deater-Deckard, Pickering, Dunn and Golding 16 An integrative review showed that father's depression following the birth was associated with his partner's depression in pregnancy and after birth.Reference Edward, Castle, Mills, Davis and Casey 18 Another integrative review reported that the incidence of paternal depression were higher in men whose partners were experiencing post-partum depression.Reference Goodman 13

To date, there have been no reports in the literature describing secular changes of both maternal and paternal hospital admissions for mental disorders over the period covering the year before pregnancy (non-parents), during pregnancy (expectant parents) and up to the first year after birth (parents) based on linked parental data. The co-occurrences of couples’ hospital admissions for mental disorders have not previously been investigated. Therefore, the aims of this study were to use linked population data from Australia's most populous state (New South Wales) to: (a) describe maternal and paternal hospital admissions for mental disorders before pregnancy, during pregnancy and after birth; and (b) compare the co-occurrence of parents’ hospital admissions for mental disorders in the perinatal period.

Method

Study population and design

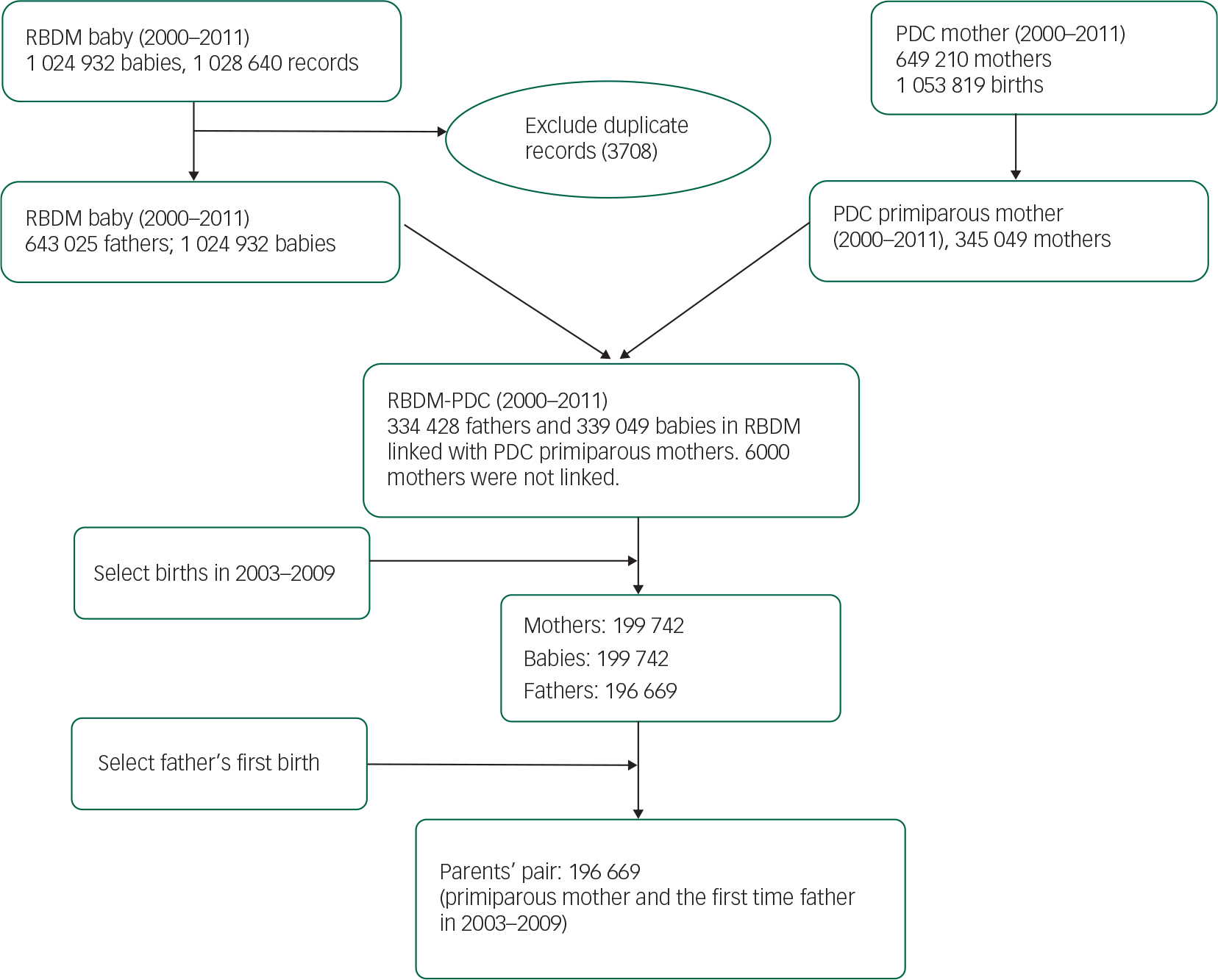

This is a population-based cohort study using linked data from the NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC), NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM) and the NSW Admitted Patients Data Collection (APDC). The study included all parents who gave birth to their first child in NSW between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2009. The details of the study population and data linkage are described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 The data linkage and study population. RBDM, New South Wales registry of births, deaths and marriages; PDC, New South Wales perinatal data collection.

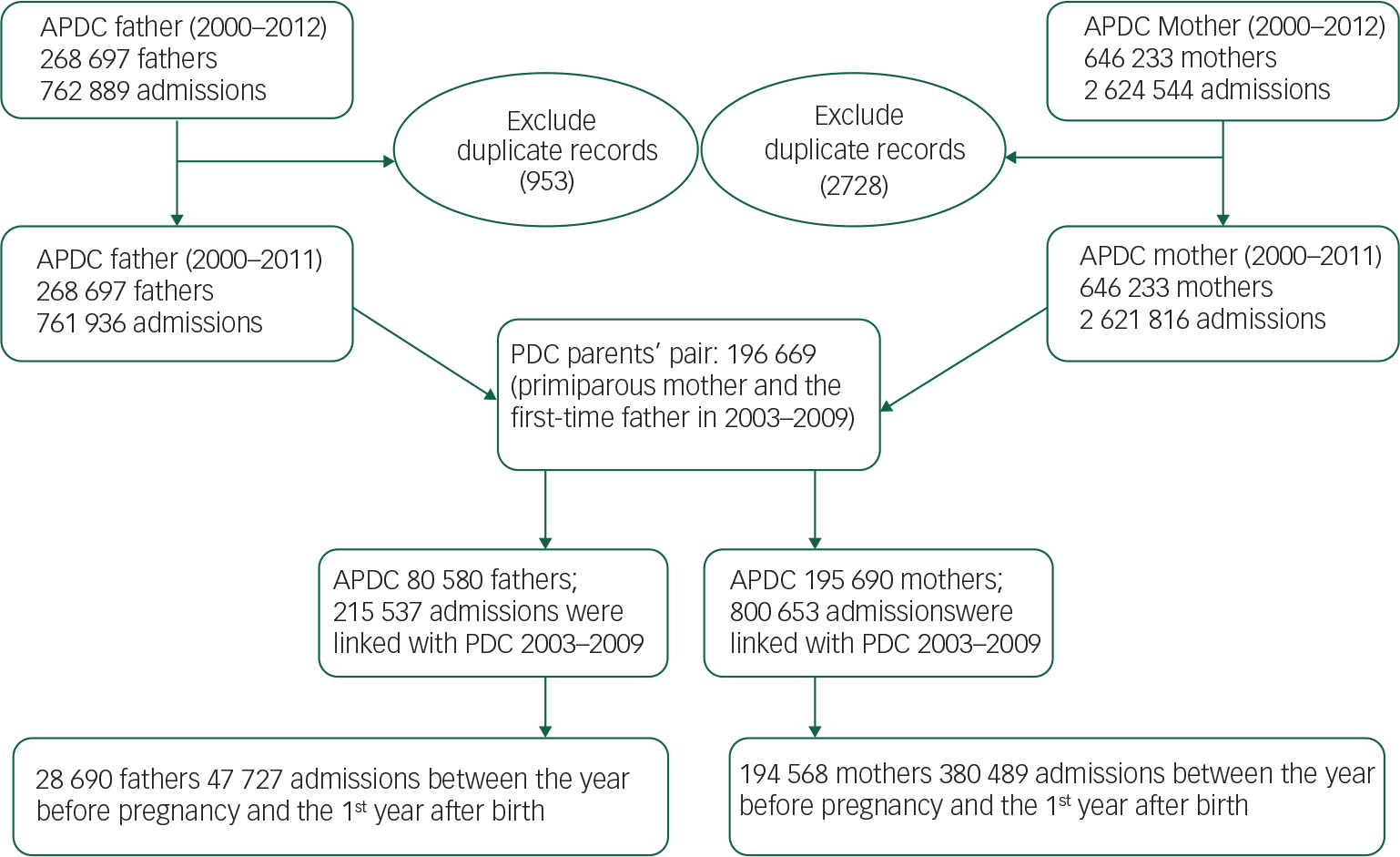

The mother's PDC birth records, which included mother's and baby's Project Person Number (PPN), were linked with RBDM which included baby's, mother's and father's PPN. The linked PDC-RBDM birth records between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2009 were linked with parents’ APDC records between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2010, so that hospital admissions for these parents could be traced back for their pregnancy period (expectant parents), the year before pregnancy (non-parents) and followed up 1 year after birth (parents). The couples were followed up over the three periods from the year before pregnancy, pregnancy to the last month of the first year after birth. The APDC records selection and data linkage are detailed in Fig. 2. Parents’ hospital admissions for mental disorders were identified by APDC records.

Fig. 2 Parents’ hospital admission data linked with birth data. APDC, New South Wales admitted patients data collection.

The PDC is a population-based surveillance system that includes all births of at least 20 weeks gestation or at least 400 g birthweight in NSW. It includes all births in public and private hospitals as well as home births, and includes information on maternal characteristics, pregnancy, labour, delivery and neonatal outcomes. The RBDM is a database of birth registrations. Under the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995, all babies in NSW must be registered within 60 days of birth, 19 and the Registry therefore includes babies’ and their parents’ information such as age and place of residence. The APDC is a routinely collected census of all hospital separations. It includes all patient hospitalisations in NSW public and private hospitals including psychiatric hospitals and admissions for same day procedures. It includes information on patient demographics, diagnoses and clinical procedures. Since 1999, the diagnoses for admissions have been coded according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). 20

The data linkage was performed by the NSW Department of Health Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) using probabilistic record linkage methods and ChoiceMaker software. 21 Identifying information from PDC and APDC data sets was included in the Master Linkage Key constructed by the CHeReL. At the completion of the process, each record was assigned a Person Project Number (PPN) to allow records for the same individual to be linked. Based on the 1000 randomly selected sample of records, the false positive rate of the linkage was 0.3% and false negative <0.5%.

Definitions

The principal diagnosis refers to the diagnosis which was chiefly responsible for APDC hospital admission. 22 Mental disorders refer to the principal diagnoses for psychiatric disorders and disorders due to substance use. The first hospital admission refers to the first hospital admission between the first month of the year before pregnancy and the last month of the year after birth.

All hospital admissions include the first hospital admission and re-admissions in the study periods. Non-parents, expectant parents and parents: the couples in the year before their first pregnancy were regarded as non-parents, during pregnancy as expectant parents and the first year after birth as the parents.

Diagnosis of mental disorders

The diagnoses for each admission in this study have been coded according to the Australian modification to the World Health Organization ICD-10 Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10-AM). 20 Parents with mental disorders were identified using ICD-10-AM diagnosis codes: (1) F10–19 [mental and behaviour disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances]; (2) F32–33 [depressive disorder]; (3) F53 [mental and behavioural disorders associated with the puerperium]; (4) F41 and F43 [anxiety and adjustment disorders]; (5) F20 and F31 [schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders]; (6) others referred to the rest F codes; (7) F00–99 [overall mental disorders].

In this study, only the hospital admission with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder between the year before pregnancy and the first year after birth was included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the rate of hospital admission (including the 95% confidence interval, CI), parents’ age and mothers’ characteristics. Person-year was used as the denominator for the analysis of rates to allow comparison between different periods or between maternal and paternal populations. The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) Statistics version 22. 23

Results

The study population were primiparous women who gave birth in NSW between 2003 and 2009 and their partners. First, primiparous mothers were selected from PDC birth records. Then the women's PDC birth records were linked with their babies’ RBDM records. Finally the births between 2003 and 2009 were selected. There were 199 742 primiparous women who met the inclusion criteria and were linked with their partners through their babies’ RBDM records. Of the 199 742 couples, there were 196 669 fathers (98.46%) who had first births. A total of 196 669 couples were included in the data analysis (Fig. 1). Women's characteristics and demographic factors are described in Table 1. The fathers (median 31.56, mean 31.95, standard deviation (s.d.)=6.64, range 13.81–82.80) were 3 years older than the mothers (median 29.02, mean 28.49, s.d.=5.78, range 12.01–56.04) (P<0.05).

Table 1 New mother's characteristics in NSW, Australia, 2003–2009

| n | % | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years* | |||

| <20 | 14 001 | 7.12 | 7.01–7.23 |

| 20–24 | 35 979 | 18.3 | 18.13–18.47 |

| 25–29 | 59 696 | 30.36 | 30.16–30.56 |

| 30–34 | 57 448 | 29.21 | 29.01–29.41 |

| 35–39 | 24 167 | 12.29 | 12.14–12.44 |

| 40–44 | 5065 | 2.58 | 2.51–2.65 |

| 45+ | 291 | 0.15 | 0.13–0.17 |

| Missing | 22 | 0.01 | |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Woman's country of birth* | |||

| Australia | 133 085 | 67.67 | 67.46–67.88 |

| Others countries | 63 584 | 32.33 | 32.00–33.00 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Remoteness* | |||

| Major cities | 137 243 | 70.7 | 70.50–70.90 |

| Inner regional | 43 086 | 22.19 | 22.01–22.37 |

| Out regional and remote | 13 803 | 7.11 | 7.00–7.22 |

| Missing | 2537 | 1.3 | 1.25–1.35 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Smoking during pregnancy* | |||

| No | 175 107 | 89.31 | 89.17–89.45 |

| Yes | 20 951 | 10.69 | 10.55–10.83 |

| Missing | 611 | 0.31 | 0.29–0.33 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Index of Relative SE Disadvantage Quintile* | |||

| Least disadvantaged | 46 102 | 23.75 | 23.56–23.94 |

| 2 | 40 650 | 20.94 | 20.76–21.12 |

| 3 | 36 778 | 18.94 | 18.77–19.11 |

| 4 | 33 424 | 17.22 | 17.05–17.39 |

| Most disadvantaged | 37 178 | 19.15 | 18.98–19.32 |

| Missing | 2537 | 1.29 | 1.24–1.34 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Mode of birth | |||

| Vaginal | 134 078 | 68.21 | 68.00–68.42 |

| Caesarean section | 62 484 | 31.79 | 31.58–32.00 |

| Missing | 107 | 0.05 | 0.04–0.06 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Maternal diabetes mellitus* | |||

| No | 195 629 | 99.47 | 99.44–99.50 |

| Yes | 1040 | 0.53 | 0.50–0.56 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Gestational diabetes | |||

| No | 187 587 | 95.38 | 95.29–95.47 |

| Yes | 9082 | 4.62 | 4.53–4.71 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

| Maternal hypertension* | |||

| No | 194 833 | 99.07 | 99.03–99.11 |

| Yes | 1836 | 0.93 | 0.89–0.97 |

| Total | 196 669 | 100 | |

* Significantly different (P<0.05).

Table 2 shows the first hospital admission rates of the couples for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders from the year before pregnancy up to the last month of the first year after birth in NSW between 2003 and 2009. Women's first hospital admission rate for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders was significantly higher than men (Table 2) (P<0.05). In the 196 669 couples, 4896 women (8.87 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 8.62–9.12) were admitted to a hospital for the principal diagnoses of a mental disorder in the period between the year before pregnancy and the last month of the first year after birth. There were 1287 men (2.33 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 2.20–2.46) who were admitted to a hospital for the principal diagnoses of a mental disorder in the same period. The women's hospital admission rate with a mental disorder was 3.81 times greater than the men's (Table 2).

Table 2 Couples’ first hospital admissions a for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders before and after birth in NSW, Australia, 2001–2010

| Admission diagnosis | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The year before pregnancy | Pregnancy | The year after birth | Overall | The year before pregnancy | Pregnancy | The year after birth | Overall | ||

| Person-year | 196 669 | 158 903 | 196 669 | 552 241 | 196 669 | 158 903 | 196 669 | 552 241 | |

| Mental and behaviour disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances (F10–19) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 1.86 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 1.42 | 0.84 | 1.10 | 1.14 |

| 95% CI | 1.67–2.05 | 0.21–0.39 | 0.51–0.73 | 0.89–1.05 | 1.25–1.59 | 0.70–0.98 | 0.95–1.25 | 1.05–1.23 | |

| Depressive disorders (F32–33) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 0.98 | 0.40 | 2.52 | 1.36 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.57 | 0.40 |

| 95% CI | 0.84–1.12 | 0.30–0.50 | 2.30–2.74 | 1.26–1.46 | 0.32–0.50 | 0.11–0.23 | 0.46–0.68 | 0.35–0.45 | |

| Mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium (F53) b | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 5.35 | 1.91 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.00–0.00 | 0.00–0.04 | 5.03–5.67 | 1.79–2.03 | |||||

| Anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41, F43) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 1.18 | 0.60 | 11.01 | 4.52 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.89 | 0.57 |

| 95% CI | 1.03–1.33 | 0.48–0.72 | 10.55–11.47 | 4.34–4.70 | 0.37–0.57 | 0.20–0.36 | 0.76–1.02 | 0.51–0.63 | |

| Schizophrenia and Bipolar affective disorders (F20, F31) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| 95% CI | 0.43–0.63 | 0.20–0.36 | 0.45–0.65 | 0.41–0.53 | 0.28–0.44 | 0.21–0.39 | 0.16–0.30 | 0.25–0.35 | |

| Others | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 1.08 | 0.38 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| 95% CI | 0.93–1.23 | 0.28–0.48 | 0.61–0.85 | 0.68–0.82 | 0.31–0.49 | 0.28–0.48 | 0.29–0.45 | 0.33–0.43 | |

| Overall mental disorders (F00–99) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 4.68 | 1.61 | 18.91 | 8.87 | 2.66 | 1.64 | 2.56 | 2.33 |

| 95% CI | 4.38–4.98 | 1.41–1.81 | 18.31–19.51 | 8.62–9.12 | 2.43–2.89 | 1.44–1.84 | 2.34–2.78 | 2.20–2.46 | |

a The first hospital admission refers to the first admission between the first month of the year before pregnancy and to the end of the 12th month after birth.

b F53 refers to the diagnosis of mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium, not elsewhere classified. The disorders occur after birth. But in this study data, three women (0.02/1000 person-year) were mistakenly recorded with the diagnosis of F53 before birth.

In the three study periods, the maternal first hospital admission rate for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders was the highest after birth (rate 18.91 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 18.31–19.51) compared with the year before pregnancy (rate 4.68 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 4.38–4.98) and during pregnancy (rate 1.61 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 1.41–1.81). For the diagnoses of depressive disorders (F32–33), anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41 and F43), the pattern was similar; the hospital admission rate was the highest in the period after birth, and lowest in pregnancy (P<0.05). The first hospital admission rate for the diagnosis of mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium (F53) was 5.35 per 1000 person-year (95% CI 5.03–5.67), one year after birth. For the diagnosis of mental and behaviour disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances (F10–19), maternal hospital admission rate in the year before pregnancy was higher than the periods in pregnancy and after birth (P<0.05). For schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders (F20, F31), maternal hospital admission rate in pregnancy was lower than the year before pregnancy and the year after birth (Table 2 and Fig. 4) (P<0.05).

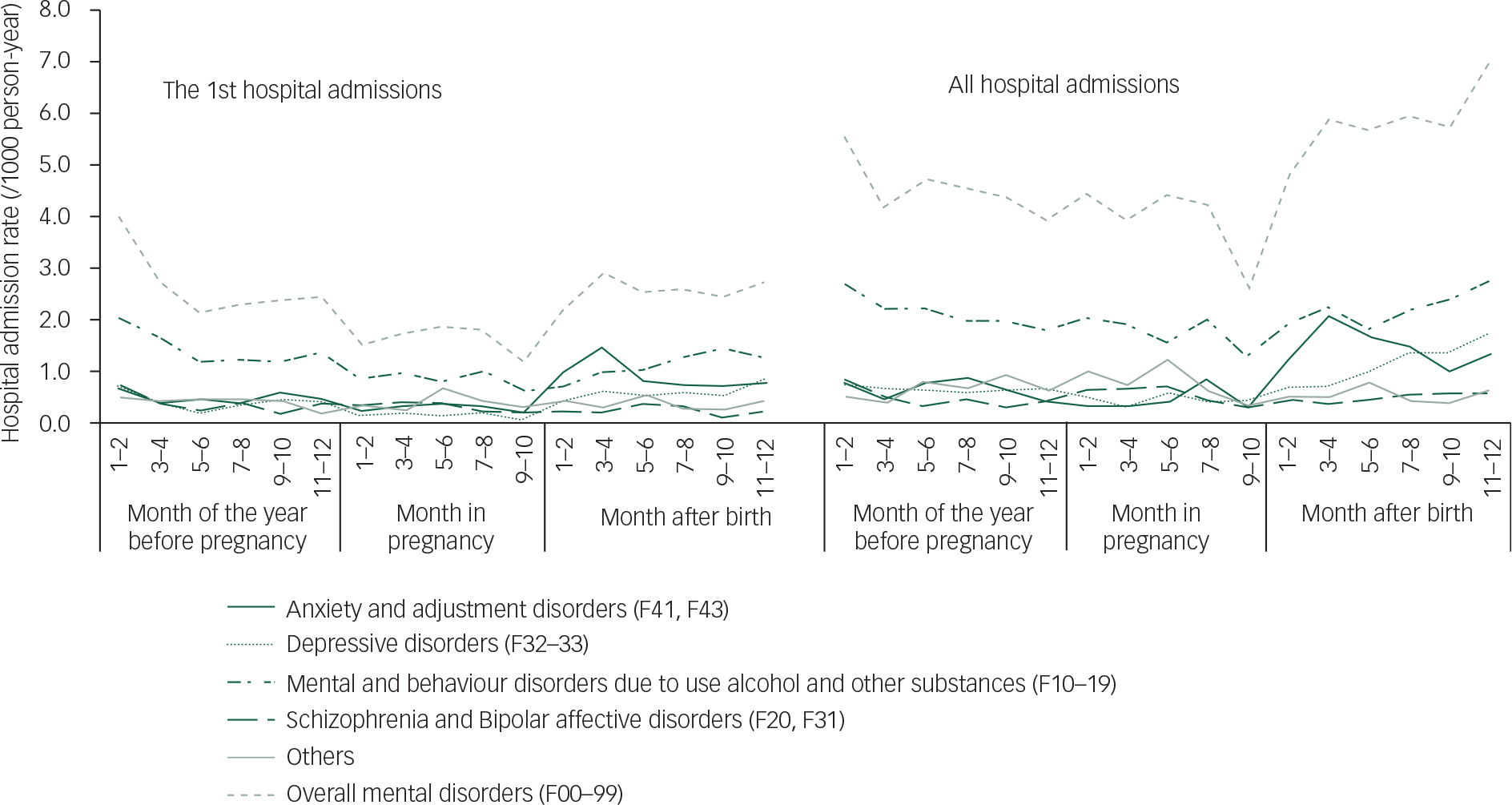

Fig. 3 Couple's hospital admissions for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders over the years before pregnancy, pregnancy and the first year after birth in NSW, Australia, 2001–2010.

The paternal first hospital admission rate for the principal diagnosis of mental disorders in pregnancy (rate 1.64 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 1.44–1.84) was lower than the year before pregnancy (rate 2.66 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 2.43–2.89) and the first year after pregnancy (rate 2.56 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 2.34–2.78). Similar to women, paternal hospital admissions for anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41, F43) after birth increased significantly compared with the time periods before birth (P<0.05). The rate change however was significantly less than for women (P<0.05). For the diagnosis of mental and behaviour disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances (F10–19) and depressive disorders (F32–33), paternal hospital admission in pregnancy was lower than the year before pregnancy and the first year after birth (P<0.05). For schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders (F20, F31), there was no significant difference in paternal hospital admission rates among the three time periods (the year before pregnancy, pregnancy and the first year after birth) (Table 2 and Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Mothers’ hospital admissions for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders before and after birth in NSW, Australia, 2001–2010. PY, person-year; NSW, New South Wales.

The maternal first hospital admission rates in the year before pregnancy and especially in the first year after birth were significantly higher than paternal first hospital admission rates (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between maternal and paternal first hospital admission rates during the period of pregnancy (Table 2).

The rate of all hospital admissions of the couples for mental disorders principal diagnoses between the year before pregnancy and the first year after birth were described in Table 3. The maternal hospital admission rate 14.14/1000 person-year (95% CI 13.83–14.45) which was significantly higher (rate ratio 2.93 times) than the paternal hospital admission rate (rate 4.83/1000 person-year, 95% CI 4.65–5.01). The change for all hospital admissions with mental disorders principal diagnoses over the periods before and after birth was similar to the first hospital admissions (Table 2). The maternal hospital admission rates in the year before pregnancy and especially in the first year after birth were significantly higher than paternal hospital admission rates (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between maternal and paternal hospital admission rates during the period of pregnancy (Table 3, Figs. 4 and 5).

Table 3 Parents’ all hospital admissions for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders before and after birth in NSW, Australia, 2001–2010

| Admission diagnosis | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The year before pregnancy | Pregnancy | The year after birth | Overall | The year before pregnancy | Pregnancy | The year after birth | Overall | ||

| Person-year | 196 669 | 158 903 | 196 669 | 552 241 | 196 669 | 158 903 | 196 669 | 552 241 | |

| Mental and behaviour disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances (F10–19) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 2.73 | 0.74 | 1.43 | 1.69 | 2.14 | 1.76 | 2.21 | 2.06 |

| 95% CI | 2.50–2.96 | 0.61–0.87 | 1.26–1.60 | 1.58–1.80 | 1.94–2.34 | 1.55–1.97 | 2.00–2.42 | 1.94–2.18 | |

| Depressive disorders (F32–33) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 1.50 | 0.80 | 4.36 | 2.32 | 0.66 | 0.46 | 1.14 | 0.77 |

| 95% CI | 1.33–1.67 | 0.66–0.94 | 4.07–4.65 | 2.19–2.45 | 0.55–0.77 | 0.35–0.57 | 0.99–1.29 | 0.70–0.84 | |

| Mental and behavioural disorders associated with puerperium (F53) a | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 0.00 | 0.02 | 6.24 | 2.23 | ||||

| 95% CI | 0.00–0.00 | 0.00–0.04 | 5.89–6.59 | 2.11–2.35 | |||||

| Anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41, F43) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 1.76 | 0.84 | 11.86 | 5.10 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 1.45 | 0.86 |

| 95% CI | 1.57–1.95 | 0.70–0.98 | 11.38–12.34 | 4.91–5.29 | 0.53–0.75 | 0.32–0.52 | 1.28–1.62 | 0.78–0.94 | |

| Schizophrenia and Bipolar affective disorders (F20, F31) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 0.84 | 0.81 | 1.12 | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| 95% CI | 0.71–0.97 | 0.67–0.95 | 0.97–1.27 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.37–0.57 | 0.43–0.65 | 0.39–0.59 | 0.44–0.56 | |

| Others | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 2.43 | 1.32 | 1.77 | 1.87 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.64 |

| 95% CI | 2.21–2.65 | 1.14–1.50 | 1.58–1.96 | 1.76–1.98 | 0.53–0.75 | 0.64–0.92 | 0.44–0.64 | 0.57–0.71 | |

| Overall mental disorders (F00–99) | Admission rate (/1000 person-year) | 9.26 | 4.53 | 26.79 | 14.14 | 4.54 | 3.96 | 5.83 | 4.83 |

| 95% CI | 8.84–9.68 | 4.20–4.86 | 26.08–27.50 | 13.83–14.45 | 4.24–4.84 | 3.65–4.27 | 5.49–6.17 | 4.65–5.01 | |

a F53 refers to the diagnosis of mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium, not elsewhere classified. The disorders occur after birth. But in this study data, three women (0.02/1000 person-year) were mistakenly recorded with the diagnosis of F53 before birth.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the maternal and paternal hospital admissions for the principal diagnosis of mental disorders during the three time periods (the year before pregnancy, pregnancy and the first year after birth). Women's hospital admissions, including first and all principal diagnoses for mental disorders, increased significantly after giving birth and peaked in the 3rd and 4th month after birth (maternal first hospital admission rate 29.84 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 28.00–31.68; maternal all hospital admission rate 38.20 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 36.12–40.28 in month 3–4 after birth) (Fig. 3). Compared with women, men's hospital admission rates were lower except during the period of pregnancy (Tables 2 and 3) and did not have the same peak in the 3rd and 4th month after birth.

Fig. 5 Fathers’ hospital admissions for the principal diagnoses of mental disorders before and after birth in NSW, Australia, 2001–2010. PY, person-year; NSW, New South Wales.

Figure 4 shows that maternal hospital admissions for mental disorders were mainly attributed to anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41 and F43); mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium (F53) and depressive disorders (F32–33).

Figure 5 showed that paternal hospital admissions for mental disorders were mainly attributed to mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol and other substances (F10–19); anxiety and adjustment disorders (F41 and F43) and depressive disorders (F32–33).

Table 4 shows the co-occurrence of mother's first hospital admissions for principal diagnoses of mental disorders with fathers. If a man was admitted to a hospital with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder, his partner was more likely to be admitted to a hospital with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder (women's hospital admission rate 12.03, 95% CI 10.21–13.85), particularly in the period after birth, compared with the women whose partner did not have the hospital admission (women's hospital admission rate 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.94).

Table 4 Co-occurrence of mothers’ hospital admissions for the first principal diagnoses of mental disorders with fathers

| Time of admission | Fathers with mental disorders (person-year) | Co-occurrence of mothers with mental disorders | Fathers without mental disorders (person-year) | Co-occurrence of mothers with mental disorders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | % | 95% CI | Mothers | % | 95% CI | |||

| Before pregnancy | 524 | 60 | 11.45 | 8.72–14.18 | 196 145 | 861 | 0.44 | 0.35–0.53 |

| In pregnancy | 195 a | 22 | 11.28 | 6.84–15.72 | 158 708 | 234 | 0.15 | 0.09–0.21 |

| After pregnancy | 503 | 65 | 12.92 | 9.99–15.85 | 196 166 | 3654 | 1.86 | 1.67–2.05 |

| Overall | 1222 a | 147 | 12.03 | 10.21–13.85 | 551 019 | 4749 | 0.86 | 0.78–0.94 |

a The number has been adjusted to person-year.

Table 5 shows the co-occurrence of father's first hospital admissions for principal mental disorder diagnoses with mothers. If a woman was admitted to a hospital with a principal diagnosis of mental disorder, her partner was also more likely to be admitted to a hospital with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder (men's hospital admission rate 3.04, 95% CI 2.56–3.52), particularly in the period before pregnancy, compared with men whose partner did not have a hospital admission for a mental disorder (men's hospital admission rate 0.21, 95% CI 0.17–0.25).

Table 5 Co-occurrence of fathers’ hospital admissions for the first principal diagnoses of mental disorders with mothers

| Time of admission | Mothers with mental disorders (person-year) | Co-occurrence of fathers with mental disorders | Mothers without mental disorders (person-year) | Co-occurrence of fathers with mental disorders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | % | 95% CI | Fathers | % | 95% CI | |||

| Before pregnancy | 921 | 68 | 7.38 | 5.69–9.07 | 195 748 | 456 | 0.23 | 0.16–0.30 |

| In pregnancy | 189 a | 9 | 4.75 | 1.72–7.78 | 158 714 | 251 | 0.16 | 0.10–0.22 |

| After pregnancy | 3719 | 70 | 1.88 | 1.44–2.32 | 192 950 | 433 | 0.22 | 0.15–0.29 |

| Overall | 4829 a | 147 | 3.04 | 2.56–3.52 | 547 412 | 1140 | 0.21 | 0.17–0.25 |

a The number has been adjusted to person-year.

Women were more likely to be impacted by their partner's mental health problems compared with men (Tables 4 and 5) (P<0.05). In other words, a man's mental disorders impacted his partner's hospital admissions for mental disorders more significantly than woman's mental disorders on her partner's (Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

This study provides a complete picture of couple's first hospital admissions for principal diagnoses of mental disorders during the year before pregnancy (non-parents), pregnancy (expectant parents) and the first year after birth (parents). Compared with non-mothers, mothers had significantly more hospital admissions for mental disorder diagnoses (mother's first hospital admission rate 18.91 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 18.31–19.51; non-mother's first hospital admission rate 4.68 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 4.38–4.98). Compared with non-fathers, fathers did not have the increased risk for hospital admissions for mental disorders (father's first hospital admission rate 2.56 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 2.34–2.78; non-father's first hospital admission rate 2.66 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 2.43–2.89). Both expectant parents were less likely to be admitted to hospitals for mental disorder diagnoses compared with non-parents (expectant mother's first hospital admission rate 1.61 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 1.41–1.81; expectant father's first hospital admission rate 1.64 per 1000 person-year, 95% CI 1.44–1.84). The non-mother's first hospital admission rate for mental disorders was 1.76 times higher than non-fathers. The mother's first hospital admission rate for mental disorders was 7.39 times higher than that for fathers. There was no significant difference in the first hospital admission rates for mental disorders between expectant parents.

The increased trend in maternal hospital admissions for mental disorders after birth is well documented in the literature.Reference Kendell, Chalmers and Platz 4 , Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Xu, Austin, Reilly, Hilder and Sullivan 7 , Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 The hospital admission rates varied over a wide range.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 The results of this study are consistent with our previous study which reported that mother's first hospital admission rate for the principal diagnoses of psychiatric disorders (excluding substance use disorders, F10–19) in the first year after birth was 1.67% (95% CI 1.63–1.71).Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 This study showed that mother's first hospital admission rate for mental disorders (including substance use disorders, F10–19) was 1.89% (95% CI 1.83–1.95) in the first year after birth (Table 2). A Danish population-based cohort study (1973–2005) also showed that the rate of mother's first-time hospital admission for mental disorders was significantly higher than during pregnancy but the rate levels (the first hospital admission rate 0.70/1000 person-year in pregnancy and 1.96/1000 person-year after birth) were significantly lower than the current study.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 The increased hospital admissions after birth were mainly attributed to an increase in mother's anxiety and adjustment disorders, mental and behaviour disorders associated with puerperium, and depression (Fig. 4).Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 , Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 Alternatively, a survey in the United States showed that there were no significant differences in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders between pregnant (25.3%), post-partum (27.5%) and non-pregnant women of child-bearing age (30.1%).Reference Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant and Hasin 5 A retrospective cohort study based on Western Australia health service data between 1990 and 2005 showed that the maternal hospital admission rate for mental disorders in the 12 months before birth was between 14 per 1000 birth (1990) and 17 per 1000 birth (2005),Reference O'Donnell, Anderson, Morgan, Nassar, Leonard and Stanley 24 which was about 9–11 times higher than the expectant mothers’ hospital admission rates for mental disorders in this study. The variation of the hospital admission rates for mental disorders may attribute to the difference in study population and time. For example, the study in Denmark was based on the data between 1973 and 2005.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 The study in Western Australia was based on the data between 1990 and 2005.Reference O'Donnell, Anderson, Morgan, Nassar, Leonard and Stanley 24 Our study was based on the data from 2003 to 2009. The study from Australia showed that the hospital admission rates for mental disorders increased significantly over the past decade.Reference Xu, Sullivan, Li, Burns, Austin and Slade 9 , Reference O'Donnell, Anderson, Morgan, Nassar, Leonard and Stanley 24 Other factors, such as the accessibility to health service, 25 physical health,Reference Woolhouse, Gartland, Perlen, Donath and Brown 8 location of residence,Reference Buist, Austin, Hayes, Speelman, Bilszta and Gemmill 26 country of birthReference Xu, Austin, Reilly, Hilder and Sullivan 7 and maternal age,Reference Xu, Austin, Reilly, Hilder and Sullivan 7 , Reference O'Donnell, Anderson, Morgan, Nassar, Leonard and Stanley 24 also impact the hospital admission rate for mental disorders.

The change of paternal hospital admissions for mental disorders before and after birth was not as significant as the rate for mothers. The paternal first hospital admissions for mental disorders did not increase significantly after birth compared with the year before pregnancy. The rate of men's all hospital admissions for mental disorders after birth increased slightly above that of non-fathers during the period of pregnancy and the year before pregnancy. This was attributed to the increase of father's anxiety and adjustment disorders, and depression after birth (Fig. 5). The result of this study was different to the report from Denmark which showed that new father's hospital admission rate for mental disorders in the first year after birth (rate 1.27 per 1000 person-year) was lower than non-fathers (rate 2.08 per 1000 person-year).Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 The difference between the study in Denmark and our study may be because of different definitions of non-fathers. In the study of Denmark, non-fathers and fathers were different individuals. In our study, non-fathers and fathers were the same individuals in different periods.

A meta-analysis which was based on survey data showed that the depression rate of men in the 2nd quarter of the year after birth (rate 26%, 95% CI 17–36%) was significantly higher than the period of pregnancy and remaining 9 months of the year after birth (rate 11%, 95% CI 6–18%, in the 1st and 2nd trimester of gestation; rate 12%, 95% CI 9–15%, in the 3rd trimester of gestation; rate 8%, 95% CI 5–11%, on the 1st quarter of the year after birth; and rate 9%, 95% CI 5–15%, between the 3rd and 4th quarter).Reference Paulson and Bazemore 27 A longitudinal population-based study of American fathers found that father's depressive symptom scores increased significantly (68%) in early fatherhood (0–5 years after having the child).Reference Garfield, Duncan, Rutsohn, McDade, Adam and Coley 14 A cohort study of 622 expectant fathers in Hong Kong showed that fathers were more likely to experience depression (EPDSA 13) at 6 weeks post-partum (5.2%) than early pregnancy (3.3%) and late pregnancy (4.1%).Reference Koh, Chui, Tang and Lee 28 A study in Portugal reported that more fathers experienced mental disorders in the first year after birth than pregnancy.Reference Areias, Kumar, Barros and Figueiredo 29 A cohort study in 5969 adults aged 18–44 in the United States showed that the rate of depression was lower in men than women.Reference Anthony and Petronis 30

Our study showed that both expectant parents were less likely to be admitted to hospital for the principal mental disorder diagnoses compared with non-parents. The result was consistent with the report which was based on Danish health service data.Reference Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors and Mortensen 6 The main reason for the decrease was the decline of maternal and paternal hospital admissions for mental and behaviour disorders due to alcohol and substance use disorders during pregnancy (Figs. 4 and 5). A study from the United States reported that pregnant women had significantly lower rates of alcohol and substance use disorders than non-pregnant women.Reference Vesga-Lopez, Blanco, Keyes, Olfson, Grant and Hasin 5 Our previous study showed that women's hospital admission rate for alcohol use disorders was 1.76 per 1000 person-year (95% CI 1.45–2.07) before pregnancy and the rate decreased to 0.49 per 1000 person-year (95% CI 0.36–0.63) during pregnancy and to 0.82 per 1000 person-year (95% CI 0.67–0.97) in the first year after birth.Reference Xu, Bonello, Burns, Austin, Li and Sullivan 31 However, studies based on community surveys, using self-report screening tools as the measure of mental disorders rather than reported diagnosis, did not show the decrease of mental disorders during pregnancy.Reference Milgrom, Gemmill, Bilszta, Hayes, Barnett and Brooks 12 , Reference O'Hara and Wisner 32

The results of this study found that parents’ mental disorders influenced each other, and women were more likely to be impacted by their partner's mental health problems compared with men. A study based on community data from England showed that men's depressive symptoms were correlated with their partners’ depressive symptoms before (r=0.24) and after (r=0.26) the birth.Reference Deater-Deckard, Pickering, Dunn and Golding 16 A cross-sectional study from Italy found that maternal distress was significantly associated with paternal distress (r=0.486).Reference Epifanio, Genna, De Luca, Roccella and La Grutta 33 A study in Japan reported that father's depression was impacted by partner's depression (adjusted odds ratio 1.91, 95% CI 1.05–3.47).Reference Nishimura, Fujita, Katsuta, Ishihara and Ohashi 34 An integrative review showed that maternal depression was a strong predictor of paternal depression during the post-partum period.Reference Goodman 13

The strength of this study is that the study data are relatively complete (all new parents in NSW were consecutively followed up for 3 years, from non-parents, expectant parents to parents) and accurate (women and men were paired by birth). As a result, both maternal and paternal hospital admission rates can be described consecutively through the stages of non-parents, expectant parents to parents. This allows a comparison of rates between men and women, and between non-parents, expectant parents and parents in hospital admissions with mental disorders. The data also allowed us to examine the impact of maternal and paternal mental disorders on each other.

There are some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results of this population study. The study neither includes epigenetic data nor data on community and out-patient mental health services, which may be differentially accessed by both populations and impact rates of hospital admission. Second, some researchers have suggested that hospital admissions for mental disorders may be over-enumerated because admissions could occur for medical reasons associated with the perinatal period.Reference Jones, Heron, Blackmore and Craddock 35 , Reference Matthey and Ross-Hamid 36 To minimise the potential overestimation of incidence rates, we included only those admissions with a ‘principal’ diagnosis of mental disorder. Birth registration data describe the family structure at the time the birth was registered, which is not necessarily the family structure at the time of the birth. The baby's father on the RBDM birth registration file was not necessarily the biological father. The data did not allow us to examine the impact of biological and non-biological fathers’ mental disorders on mothers respectively.

The incidence rate of mothers’ mental disorders after birth increased more significantly than the fathers’ rate. There was an association between mother's mental disorders and father's mental disorders suggesting that development and testing of parents-based intervention would be important to explore to address family well-being.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank data custodians of the Ministry of Health and staff of the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CheReL) for providing the data, undertaking data linkage and providing advice. We acknowledge the families who have contributed their data and professional staff who were involved in the data collection and management for this research.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.