Background

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a relatively common psychiatric disorder characterised by obsessions and compulsions.1 OCD often causes distress and impairment in academic, social and family functioning,Reference Piacentini, Bergman, Keller and McCracken2 and increases the risk of suicide.Reference Fernandez de la Cruz, Rydell, Runeson, D'Onofrio, Brander and Ruck3 About 70% of OCD patients had a childhood onset,Reference Taylor4 and the disorder often persists if left untreated.Reference Pinto, Mancebo, Eisen, Pagano and Rasmussen5

International guidelines recommend cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as the first-line intervention for paediatric OCD.6 CBT for paediatric OCD has been evaluated in more than 25 trials, consistently showing overall large effect sizes (within-group g = 2.43) and high response rates.Reference Öst, Riise, Wergeland, Hansen and Kvale7 For young children with OCD (ages ranging from three to eight years), three randomised trials have indicated that family-based CBT is superior to relaxation trainingReference Freeman, Sapyta, Garcia, Compton, Khanna and Flessner8, Reference Freeman, Garcia, Coyne, Ale, Przeworski and Himle9 and treatment as usual,Reference Lewin, Park, Jones, Crawford, De Nadai and Menzel10 with moderate to large within-group effect sizes (g = 0.53–1.80). One recent trial showed that family interventions also have a positive effect for older children and adolescents.Reference Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken and Piacentini11 One important feature in these adapted protocols is the strong focus on parent behaviours, such as increasing positive reinforcement contingencies and reducing family accommodation and criticism.

Unfortunately, the availability of CBT is limited and the majority of patients do not have access to this evidence-based treatment.Reference Schwartz, Schlegl, Kuelz and Voderholzer12 Barriers to accessing CBT include geographical and psychosocial factors,Reference Goodwin, Koenen, Hellman, Guardino and Struening13 as well as stigma.Reference Salloum, Johnco, Lewin, McBride and Storch14 One study found that the delay between symptom onset and receiving treatment was as long as 3.7 years for children and adolescents.Reference Micali, Heyman, Perez, Hilton, Nakatani and Turner15 This is especially problematic in light of the suspected positive relationship between symptom duration and treatment response, i.e. the longer the paediatric patient has OCD symptoms, the less chance of them responding to CBT.Reference Stewart, Geller, Jenike, Pauls, Shaw and Mullin16 Even when patients are offered some form of CBT in non-specialist settings, the vast majority receive suboptimal CBT, for example, with insufficient emphasis on exposure and response prevention techniques.Reference Krebs, Isomura, Lang, Jassi, Heyman and Diamond17

Internet-delivered CBT

One way to increase the availability of CBT for paediatric OCD is to use technology-based approaches, such as video-conferencing,Reference Comer, Furr, Kerns, Miguel, Coxe and Elkins18, Reference Storch, Caporino, Morgan, Lewin, Rojas and Brauer19 telephone CBT,Reference Turner, Mataix-Cols, Lovell, Krebs, Lang and Byford20 and Internet-delivered CBT (ICBT).Reference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21–Reference Rees, Anderson, Kane and Finlay-Jones23 Video-conferencing and telephone CBT provide an opportunity for non-office-based real-time sessions with a therapist, where the content and duration of the sessions are approximately the same as in traditional face-to-face CBT. ICBT has the same content as regular face-to-face CBT, but the material provided resembles an online self-help book. The treatment is usually supported by an online therapist, who asynchronously responds to messages and reviews homework assignments via an integrated email system within the ICBT online platform.Reference Andersson24 In ICBT, the amount of therapist support is only a fraction of that in traditional face-to-face CBT, resulting in considerable cost savings.Reference Hedman, Ljótsson and Lindefors25, Reference Lenhard, Ssegonja, Andersson, Feldman, Rück and Mataix-Cols26 Therapist-supported ICBT has shown promising results in children and adolescents with a range of psychiatric problems,Reference Vigerland, Lenhard, Bonnert, Lalouni, Hedman and Ahlen27 but there have been few studies compared with the adult field.Reference Hedman, Ljótsson and Lindefors25

Our research group has previously developed and evaluated an ICBT programme for adolescents (aged 12–17) called BIP (Barninternetprojektet in Swedish) OCD. BIP OCD includes 12 chapters for adolescents and five chapters for their parents, who support their children throughout the treatment. Results from one open pilot trial (N = 21) and a subsequent waitlist-controlled randomised trial (RCT; N = 67) showed that BIP OCD was efficacious in reducing OCD symptoms.Reference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21, Reference Lenhard, Vigerland, Andersson, Rück, Mataix-Cols and Thulin22 In the RCT, the therapist support time was on average 17.5 min per patient per week, suggesting that it could be a cost-effective intervention for adolescents with OCD.Reference Lenhard, Ssegonja, Andersson, Feldman, Rück and Mataix-Cols26

Aims

One important research gap in the literature is whether this form of ICBT may also be suitable for younger children with OCD. The aim of this study, therefore, was to adapt BIP OCD to suit the developmental needs of younger children aged 7–11 with OCD, and to evaluate its feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy in an open trial.

Method

Trial design

The present study used an open trial design. It was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr 2015/470-31) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02663167).

Participants

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had a primary DSM-5 diagnosis of OCD,1 had a total score ≥16 on the Children's Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS),Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman28 were between 7 and 11 years old, had the ability to understand Swedish, had daily access to the internet and had a parent that could co-participate in the treatment. Participants on psychotropic medication were allowed in the study as long as they had been on a stable dose during the 6 weeks prior to baseline assessment. Exclusion criteria were: (a) a diagnosis of a comorbid autism spectrum disorder, psychosis, bipolar disorder, severe eating disorder, organic brain disorder, or intellectual disability; (b) acute suicidal ideation; (c) CBT for OCD (including exposure with response prevention) within the past 12 months; or (d) ongoing psychological treatment for OCD or another anxiety disorder.

The study took place at a clinical research unit within the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) in Stockholm, Sweden.

Measures

Diagnosis of OCD was made according to DSM-5 criteria1 using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children (MINI-KID).Reference Sheehan, Sheehan, Shytle, Janavs, Bannon and Rogers29 As part of the pre-assessment, the parents also answered questions about autistic symptoms in their children using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ-10).Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen30

Clinician-rated measures were assessed pre-treatment, post-treatment and at 3-month follow-up by a clinical psychologist at the clinic. The participants also completed online child- and parent-rated questionnaires at these times.

The primary outcome was the CY-BOCS,Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman28 which is a semi-structured clinician-rated measurement that is used to assess symptom severity in paediatric OCD. The CY-BOCS has shown good to excellent interrater reliability and a high internal consistency.Reference Scahill, Riddle, McSwiggin-Hardin, Ort, King and Goodman28 The internal consistency in the current sample was good (α = 0.74). The clinicians in the study were trained in CY-BOCS. All the interviews were audiotaped and a third of them (N = 11) were re-rated by another clinician to assess the reliability. The intraclass coefficient was 0.99, P < 0.001, which is excellent according to statistical guidelines.Reference Shrout and Fleiss31

Secondary clinician-rated outcome measures of global functioning included the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS),Reference Shaffer, Gould, Brasic, Ambrosini, Fisher and Bird32 the Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI-S) and the Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I).Reference Guy33 OCD symptom severity was assessed weekly via the child-rated Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory – Child Version (OCI-CV)Reference Foa, Coles, Huppert, Pasupuleti, Franklin and March34 and the parent-rated Children's Obsessional Compulsive Inventory Revised – Parent Version (ChOCI-R-P).Reference Shafran, Frampton, Heyman, Reynolds, Teachman and Rachman35 Family accommodation was measured via the Family Accommodation Scale – Self Rated (FAS-SR)Reference Pinto, Van Noppen and Calvocoressi36 answered by the parents, and impairment of functioning due to OCD was assessed using the Education, Work, and Social Adjustment Scale – Child and Parent Version (EWSAS-C/P), an adaptation of the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist37 Depressive symptoms were measured with both the child-rated Child Depression Inventory – Short Version (CDI-S)Reference Kovacs38 and the parent-rated version of the Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (MFQ).Reference Angold, Costello, Messer, Pickles, Winder and Silver39 Internal consistency for secondary outcome measures in the present sample were as follows: OCI-CV, α = 0.82; ChOCI-R-P, α = 0.87; FAS-SR, α = 0.67; EWSAS-C, α = 0.61; EWSAS-P, α = 0.74; CDI-S, α = 0.77; and MFQ, α = 0.90. All child- and parent-rated measures were administered online.

Qualitative questions about treatment credibility were administered at week 3, and qualitative questions about treatment satisfaction were administered post-treatment to both children and parents. Assessments of adverse events were made using the Safety Monitoring Uniform Report Form (SMURF)Reference Bostic40 mid-treatment (by telephone) and post-treatment (at the clinician visit).

Procedure

Information about the study was advertised on the clinic webpage (www.bup.se/bip) and in a newspaper in Stockholm, Sweden. Participants could either self-refer to the study using an online application or be referred by a CAMHS clinician.

An initial telephone interview was conducted with a parent to discuss eligibility. If considered suitable, the child and their parent(s) were given an appointment with a clinical psychologist at the clinic. The aim of the clinician visit was to (a) verify the OCD diagnosis; (b) assess OCD symptom severity; (c) assess comorbid psychiatric disorders; (d) provide information about the study; and (e) decide on inclusion or exclusion. Written informed consent was signed prior to inclusion. The treatment started within 1 week after inclusion.

After 12 weeks of treatment, post-treatment measures were administered, including clinician-rated measures at the clinic and self- and parent-rated online measures. The same procedure was repeated at 3-month follow-up. For practical reasons (inability to come to the clinic), one of the 11 follow-up assessments was done by telephone (which has been shown in previous studies to be a reliable assessment methodReference Hajebi, Motevalian, Amin-Esmaeili, Hefazi, Radgoodarzi and Rahimi-Movaghar41).

Intervention

BIP OCD Junior is delivered through a secure internet platform specifically developed for delivering ICBT treatments to children and adolescents with psychiatric and behavioural difficulties (www.barninternetprojektet.se). The platform was designed to have an age-appropriate appearance and consists of texts, films, illustrations and exercises that make the programme interactive.

In BIP OCD Junior, the child and the parent have 12 different chapters each, which are offered consecutively and delivered through separate login accounts. Following recommendations from established guidelines,6 the intervention consists of psychoeducation, exposure with response prevention and relapse prevention chapters. The main difference compared with the original adolescent version of BIP OCDReference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21, Reference Lenhard, Vigerland, Andersson, Rück, Mataix-Cols and Thulin22 is the greater emphasis on parental support, by increasing the number of parent-dedicated chapters and involving parents more throughout the treatment. The parents are encouraged to work ahead with the treatment in order to be prepared and to help the child with their corresponding chapter afterwards. The content of the chapters is specifically designed for the parents and the children. The parents receive detailed psychoeducation and information on strategies to help coach their child during exposure tasks, whereas the children receive a more general and ‘hands on’ explanation of OCD and how to treat it, with less text, more illustrations and age-appropriate language. An overview of the chapters and example screenshots from the intervention are presented in the Supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.10.

Throughout the treatment, the family has asynchronous contact with a licensed clinical psychologist with experience in treating OCD. The psychologist responds to email messages in the encrypted platform within 24 h (weekdays), contacts the participant if there has not been any activity in the internet platform for 3 or 4 days, and calls the family if needed (e.g. for further clarification of the treatment content or in case of adverse events).

Sample size

We used the lower margin of the confidence interval of the effect size in previous BIP OCD trials for adolescents as a conservative proxy of anticipated effects in this study. The power calculation to determine the sample size was originally based on the results from the pilot study.Reference Lenhard, Vigerland, Andersson, Rück, Mataix-Cols and Thulin22 Given 95% power and two-sided 5% alpha, the power calculation (based on paired t-tests and an effect size of d = 1.5) showed that eight participants would be required to find the estimated effect. This number was later increased to N = 16, owing to the lower effect size (d = 1.00) in the RCT,Reference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21 allowing for drop-out and covering possible data attrition.

Statistical methods

Mixed-effects models with a fixed effect of time and random effects of individuals were used to test changes in continuous outcome measures. Alpha (two-tailed) was set at P < 0.05 for all analyses. Within-group effect sizes were estimated with Cohen's d. Reference Cohen42 We used the recent expert consensus criteria to define treatment response (≥35% decrease on the CY-BOCS plus a CGI-I rating of 1 or 2) and remission (a score of ≤12 on the CY-BOCS plus a CGI-S rating of 1 or 2).Reference Mataix-Cols, Fernandez de la Cruz, Nordsletten, Lenhard, Isomura and Simpson43

All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Sample characteristics and study flow

Participants were 11 children recruited from all over Sweden between February 2016 and April 2016. Since no participants dropped out, the recruitment stopped before reaching N = 16, based on the original power analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (N = 11)

OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; AQ-10, Autism Spectrum Quotient; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

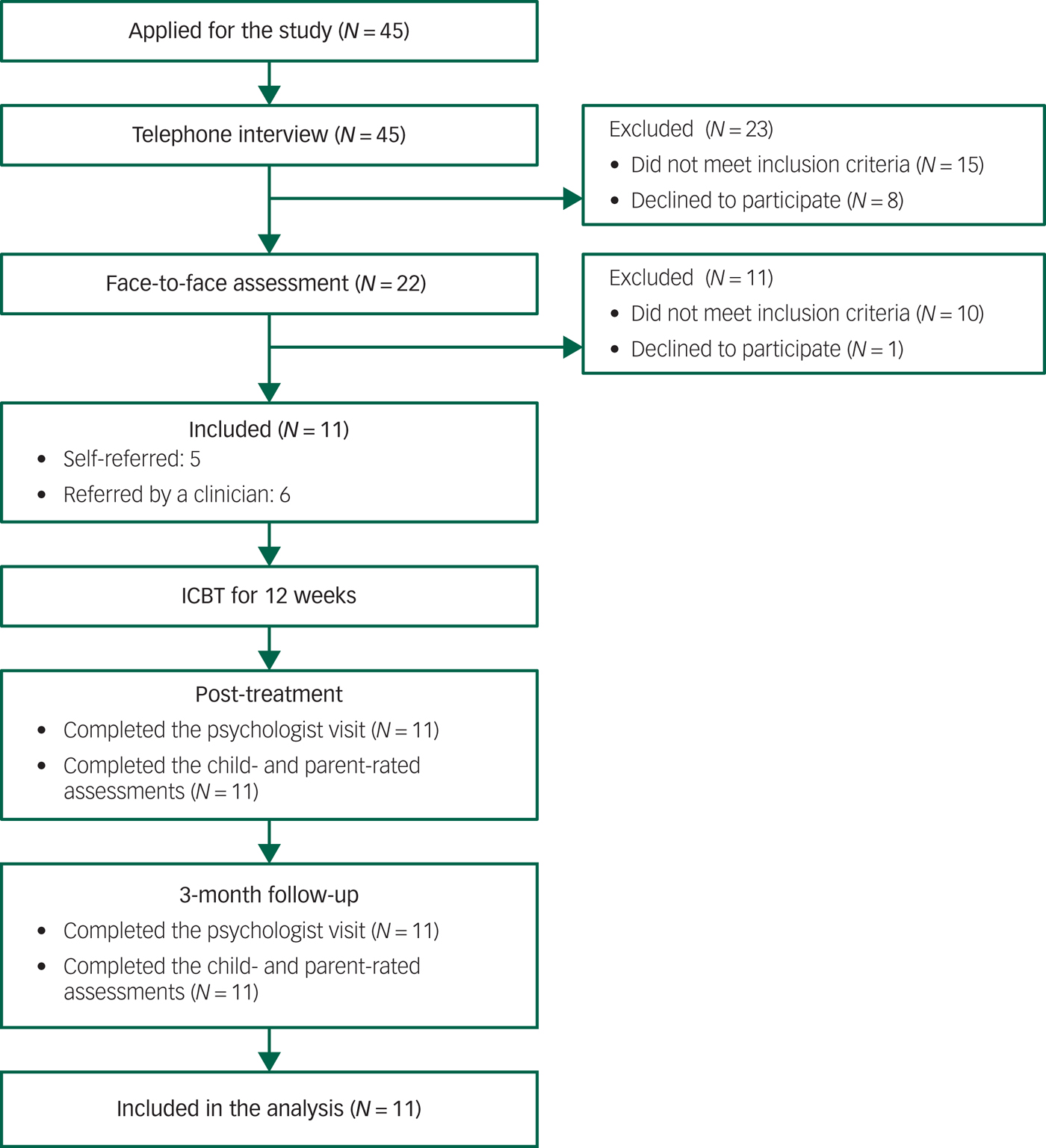

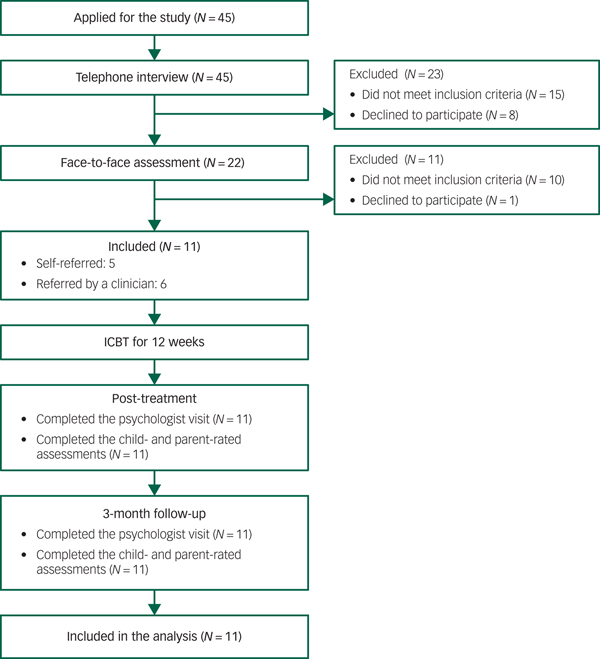

Figure 1 shows the study flow. There was no data loss post-treatment or at 3-month follow-up on any of the outcome measures. One participant adjusted medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) during the course of the trial.

Fig. 1 Study flow.

Primary outcomes

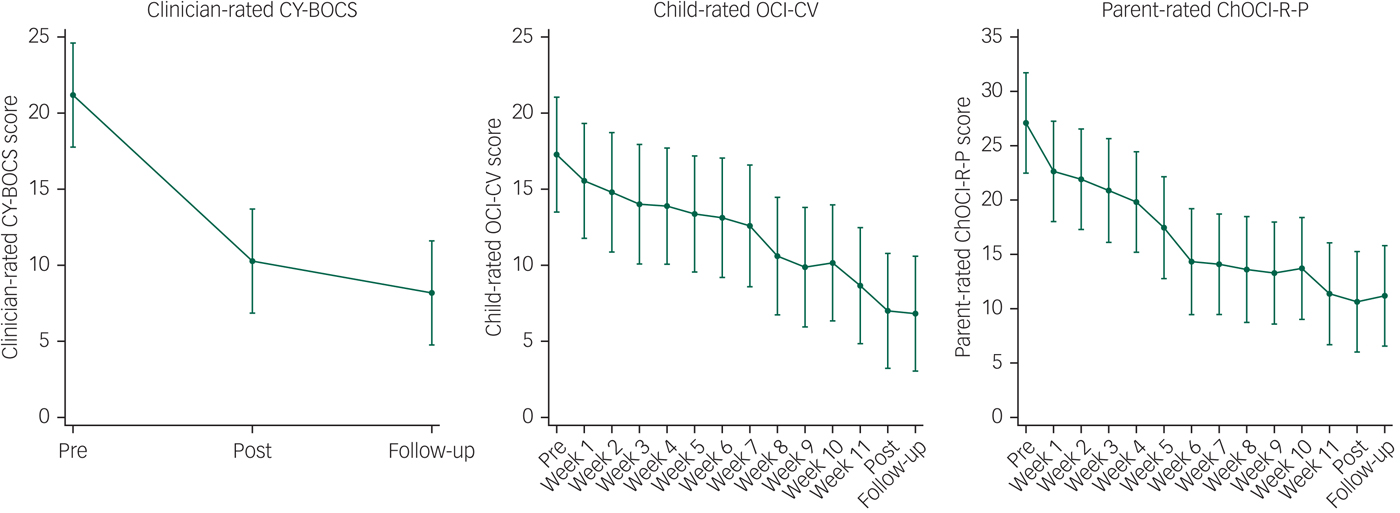

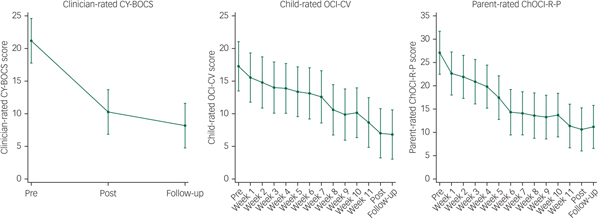

Treatment outcomes and effect sizes for all outcome measures are presented in Table 2. There was a significant decrease in clinician-rated OCD symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment (B = −10.91, Z = −5.92, P < 0.001, 95% CI −14.52 to −7.30), corresponding to a within-group effect size of d = 1.86, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.86. Symptom improvement was maintained during follow-up, with a non-significant trend towards further improvement between post-treatment and 3-month follow-up (B = −2.09, Z = −1.14, P = 0.256, 95% CI −5.70 to 1.52; see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Clinician-, child- and parent-rated measures of OCD symptom severity. Follow-up was at 3 months.

Table 2 Primary and secondary outcome measures

CY-BOCS, Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression – Improvement; OCI-CV, Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory – Child Version; CDI-S, Child Depression Inventory – Short Version; EWSAS-C, Education, Work, and Social Adjustment Scale – Child Version; ChOCI-R-P, Children's Obsessional Compulsive Inventory Revised – Parent Version; FAS-SR, Family Accommodation Scale – Self Rated; MFQ, Mood and Feeling Questionnaire; EWSAS-P, Education, Work, and Social Adjustment Scale – Parent Version.

* P < 0.01.

** P < 0.001.

Secondary outcomes

There were significant effects on the weekly measures of child-rated (B = −0.75, Z = −11.05, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.88 to −0.61) and parent-rated (B = −1.24, Z = −12.88, P < 0.001, 95% CI −1.43 to −1.05) OCD symptom severity (Fig. 2). There were significant improvements on the other secondary outcome measures, except for child-rated depressive symptoms. The largest effect was observed on family accommodation (d = 2.67). All results were maintained at 3-month follow-up.

Treatment response and remission

At post-treatment, eight participants (72.7%, 95% CI 35.4 to 92.8) were classed as responders and five participants (45.5%, 95% CI 16.8 to 77.4) were classed as being in remission. The proportion of responders was the same at 3-month follow-up, whereas the number of participants being in remission had increased to seven (63.6%, 95% CI 28.8 to 88.3) during the follow-up period.

Treatment completion and clinician support

Both the parents and the children completed on average 11 chapters out of 12 (s.d. = 1.8–2.0). The average clinician time per participant was 264.3 min (s.d. = 63.4) in total, which is on average 22.0 min per week per participant. This included online correspondence with the children and parents as well as telephone calls. A post hoc analysis showed that the therapists spent more time communicating with the parents (M = 172.3, s.d. = 39.1) than with the children (M = 92, s.d. = 35.0), t(10) = 6.91, P < 0.001.

Treatment credibility and satisfaction

Overall, the children and parents rated the treatment as being highly credible. To the question ‘How much do you expect you/your child will improve with this treatment?’ (from 1 = not at all improved to 5 = very much improved), the children answered on average 4.4 (s. d. = 0.5) and the parents 4.4 (s.d. = 0.7). At post-treatment, children rated the item ‘In general, what did you think of the Internet treatment?’ (from 1 = ‘very bad’ to 5 = ‘very good’) on average 4.4 (s.d. = 0.7) and the parents 4.8 (s.d. = 0.4). To the question ‘Would you recommend this treatment to a friend who also has OCD/a friend who has a child that also has OCD?’ (from 1 = ‘no, not at all’ to 5 = ‘yes, absolutely’), both the children and the parents rated on average 4.8 (s.d. = 0.4).

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported at mid- or post-treatment. Three parents reported mild adverse events. One reported increased family conflicts during the first weeks of exposure, and another reported increased OCD-related symptoms owing to increased awareness from the parent. The third reported increased sensitivity to smells, headache, irritability and sleep problems, as well as reduced appetite, which occurred at the same time as changes in ADHD medication during the treatment.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to adapt an existing ICBT programme for adolescents with OCD to suit the developmental needs of younger patients aged 7–11, and to evaluate its feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy in a pilot study.

Both children and parents felt that the intervention was credible and reported high levels of satisfaction post-treatment. Together with the low attrition, these results indicated that BIP OCD Junior is an acceptable and feasible intervention for the targeted age group. In addition, the results showed large reductions in clinician-rated OCD symptoms post-treatment. Similar improvements were observed on child- and parent-rated measurements of OCD symptoms, general functioning and family accommodation. On measurements of depressive symptoms, there was a significant improvement on the parent-rated but not the child-rated questionnaire, probably owing to the low baseline scores. The results were maintained at 3-month follow-up. The effect sizes are comparable to those of the BIP OCD RCTReference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21 and to what would be expected in both face-to-face treatment for paediatric OCDReference Öst, Riise, Wergeland, Hansen and Kvale7 and treatments specifically tailored to very young children.Reference Freeman, Sapyta, Garcia, Compton, Khanna and Flessner8–Reference Lewin, Park, Jones, Crawford, De Nadai and Menzel10

The results from this open trial are promising, as ICBT has considerable potential to increase the availability of evidence-based treatment for the young OCD population, especially for those who do not have access to treatment owing to geographical distance and those who experience shame and resistance to seeking treatment because of other psychosocial factors.Reference Goodwin, Koenen, Hellman, Guardino and Struening13, Reference Salloum, Johnco, Lewin, McBride and Storch14 Thus, this internet-delivered intervention has promise as a low-threshold alternative and provides an opportunity for children to receive early intervention before the OCD symptoms become more persistent and difficult to treat.Reference Stewart, Geller, Jenike, Pauls, Shaw and Mullin16 From the larger societal perspective, this could potentially reduce the long-term need for child- and adolescent psychiatric services, thereby freeing resources for the more difficult cases.

One important observation in this study is that the remission rates increased between post-treatment (45.5%) and the 3-month follow-up (63.6%), a phenomenon which is not usually seen in face-to-face trials.Reference Öst, Riise, Wergeland, Hansen and Kvale7 This delayed treatment response has been consistently shown in previous ICBT trials for adolescent OCDReference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21, Reference Lenhard, Vigerland, Andersson, Rück, Mataix-Cols and Thulin22 and childhood anxiety disorders,Reference Vigerland, Ljotsson, Thulin, Ost, Andersson and Serlachius44 and could be an indication that the primary endpoint for ICBT in paediatric populations should to be delayed to 3 months after the end of the treatment in order to provide a more reliable estimate of the treatment effect.

The therapist time in the trial was about one-third of what is expected in face-to-face treatment, and similar to other ICBT trials for adolescent OCD.Reference Lenhard, Andersson, Mataix-Cols, Rück, Vigerland and Högström21, Reference Lenhard, Vigerland, Andersson, Rück, Mataix-Cols and Thulin22 An interesting aspect of ICBT is that, although it is often called a ‘low-intensity’ intervention, the treatment is often quite intensive in the sense that patients get a response from the therapist within 24 h. Thus, owing to its internet format, the programme has a unique potential to provide families with fast feedback, coaching and problem-solving on a daily basis, despite the low overall use of therapist resources.

Post hoc findings showed that the therapists spent significantly more time communicating with the parents than with the children. Our clinical impression was that parental involvement is an important factor for successful treatment with BIP OCD Junior. Even though the literature on childhood anxiety suggests that there is no clear additional effect of parental involvement in CBT,Reference Thulin, Svirsky, Serlachius, Andersson and Öst45 there are at least four treatment studies showing positive results on interventions that specifically target parental behaviours in paediatric OCD.Reference Freeman, Sapyta, Garcia, Compton, Khanna and Flessner8–Reference Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken and Piacentini11 In addition, there are treatment protocols that only involve parents, with the main aim to reduce family accommodation.Reference Lebowitz46 Thus, this study replicates and extends the previous literature on family interventions in the treatment of young children with OCD. Our clinical impression is that parents play an important part in ICBT for paediatric OCD and that their role should receive special attention. The use of parental strategies such as positive reinforcement, reducing criticism and focusing on family processes such as accommodating behaviours, as well as problem-solving techniques, might have contributed to the efficacy of and adherence to the treatment. To our knowledge, no study has specifically investigated the role of parental involvement in ICBT, indicating that more research on this particular topic is warranted. One idea for future research would be to use a time-lagged design and closely assess the change in parental behaviours during ICBT for paediatric OCD, and correlate this with outcome. Another important step would be to conduct a dismantling study and randomise patients to BIP OCD with or without parental strategies components, as has been done previously in traditional CBT for OCD.Reference Peris, Rozenman, Sugar, McCracken and Piacentini11

The main limitations in this study were the absence of a control condition and the use of unblinded assessors. However, self- and parent-reported measures showed similar results to the clinician ratings. Moreover, given the persistent nature of OCD, it is unlikely that the large effect sizes obtained in this study could be entirely explained by spontaneous fluctuations.Reference Stewart, Geller, Jenike, Pauls, Shaw and Mullin16 Two of the secondary outcome measures, FAS-SRReference Pinto, Van Noppen and Calvocoressi36 and EWSAS-C/P,Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist37 have only been validated in adult populations and should therefore be interpreted cautiously, although their internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable to good. Another limitation is the limited sample size and the characteristics of participants, which affect the generalisability of the findings. More specifically, the sample in this study had a slightly lower baseline CY-BOCS score than has been found in face-to-face trials for very young children.Reference Freeman, Sapyta, Garcia, Compton, Khanna and Flessner8, Reference Lewin, Park, Jones, Crawford, De Nadai and Menzel10 Future research should therefore investigate for which patients ICBT works optimally, and focus on investigating whether ICBT is a viable option only for individuals with moderate symptom severity or whether it also could be an effective intervention for OCD patients at the more complex end of the symptom severity spectrum. One interesting aspect would be to implement ICBT in a stepped care model.Reference Mataix-Cols and Marks47 However, research on stepped care, in both OCD and other mental health conditions, has been lagging significantly behind. Thus, this remains to be investigated in large-scale randomised trials.

In summary, this is to our knowledge the first study investigating the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a developmentally tailored parent- and therapist-guided ICBT intervention for young children with OCD. The results replicate and extend previous findings on ICBT for adolescents with OCD, and suggest that this may also be a feasible and effective treatment for young children. The therapist time to treat each participant was about a third of what would be expected in a face-to-face treatment, indicating that this could be a potentially cost-effective treatment. A next step would be to establish the relative efficacy and cost-effectiveness of this treatment compared with face-to-face CBT.

Funding

The project was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (Forte 2014-4052).

Acknowledgements

We thank psychologists Sarah Vigerland and Maral Jolstedt for assistance with assessments, and Lotta Wiberg-Spangenberg, Johanna Crafoord and Maria Silverberg-Mörse at the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service in Stockholm for support during the study.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.10.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.