The progressive loss of previously acquired developmental milestones and competencies is a concerning clinical picture in child psychiatry and neurology, posing diagnostic and intervention challenges. It may suggest an underlying neurological aetiology denoted by the term ‘progressive intellectual and neurological deterioration’.Reference Holland and Brown1 There is evidence for developmental regression, particularly early regression during the first 2 years of life in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), epileptic encephalopathies, genetic syndromes such as Rett's syndrome and Phelan McDermid syndrome, and late regression in Down syndrome.Reference Zhang, Bedogni, Boterberg, Camfield, Camfield and Charman2–Reference Furley, Mehra, Goin-Kochel, Fahey, Hunter and Williams4 Apparent developmental and behavioural regression is observed in childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS)Reference Slomiak, Matalon and Roth5–Reference Jha, Kunwar and Dhonju7 and post-traumatic stress disorder,Reference Holland and Brown1,Reference Feldman and Vengrober8 although there is a paucity of systematic literature on this phenomenon.Reference Aneja, Singhai and Paul6

The National Institute of Mental Health COS longitudinal study, the largest study of COS to date, reported a prevalence of 0.04%.Reference Fernandez, Drozd, Thümmler, Dor, Capovilla and Askenazy9–Reference Gordon, Frazier, McKenna, Giedd, Zametkin and Kaysen11 COS (onset <13 years) is rare in occurrence, and symptom dimensions include both positive and negative symptoms, with disorganisation being less common.Reference Craddock, Zhou, Liu, Gochman, Dickinson and Rapoport12 Developmental deviance, especially in the speech and language domains, and poor premorbid adjustment before illness onset have been reported in COS.Reference Vourdas, Pipe, Corrigall and Frangou13,Reference Driver, Gogtay and Rapoport14 The diagnosis of psychotic symptoms in children is often complex because of the symptomatic overlap with other emotional, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. When psychotic symptoms are associated with developmental regression, the diagnostic dilemma becomes far more pronounced. Depression in pre-pubertal children, especially among children with atypical neurodevelopment with severe psychomotor retardation, catatonic symptoms and hallucinatory behaviours is an important differential.Reference Rao and Chen15,Reference Weiss and Garber16

Regression in the socio-communication domain is commonly seen in ASD, termed ‘autistic regression’.Reference Matson and Kozlowski17 Meta-analytic reviews report prevalence rates of 30–32.2% of regression in ASD, with an average age at onset of 19.8 months.Reference Barger, Campbell and McDonough18,Reference Tan, Frewer, Cox, Williams and Ure19 Prospective designs may have better potential to capture more subtle skill loss, particularly early socio-communication behaviours, compared with retrospective studies.Reference Pearson, Charman, Happé, Bolton and McEwen20

The phenomenon of autistic regression does not explain the later age of onset at regression, which occurs in a subset of children. Theodore Heller first described this phenomenon ‘dementia infantalis’ in six previously normal children who presented with developmental regression.Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21 In the ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR, the disorder was termed childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD).Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21 Misdiagnosis of CDD as COS, potentially attributable to the severe social impairment and withdrawn behaviour accompanied by stereotypic movements resembling symptoms of psychosis, have been reported.Reference Sawant, Parker and Kulkarni22 Also, psychotic symptoms were observed in about 33% of children who received a diagnosis of CDD.Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21,Reference Malhotra and Gupta23,Reference Rosman and Bergia24

Diagnostic conundrums in late-onset developmental regression

With the advent of technology, causes for later-onset developmental regression, such as autoimmune encephalitis, neurometabolic and neurodegenerative disorders, were increasingly identified. CDD as a distinct diagnosis has been a subject of debate because of its shared characteristics with ASD, such as core socio-communication impairments, comorbid intellectual disability and epilepsy; thus, CDD was subsumed under ASD. Although the debate on the diagnostic validity continues, CDD does have features supporting it as distinct from ASD.Reference Malhotra and Gupta23–Reference Volkmar and Cohen25 Despite increasing scientific and clinical interest, developmental regression continues to pose multiple challenges. Atypical to what is currently understood about this phenomenon, a subset of children continue to present with later-onset regression in the background of neurotypical development, with no identifiable neurological causes.

This paper describes a large case series of ten children who presented with late-onset developmental regression (>6 years of age) in the background of neurotypical development, their phenomenology, clinical course and outcome at 1-year follow-up. Similar presentations have been reported earlier; however, the age at onset of regression was much earlier (mean age 36 months), with gaps in information on complete aetiological evaluation and longitudinal course and outcome.Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21,Reference Rosman and Bergia24 The paper discusses key considerations for CDD as a ‘transitory’ and ‘non-aetiological’ diagnosis, and the need for longitudinal evaluation for a more reliable diagnostic ascertainment in this subset of children.

Method

The study was conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, a tertiary care teaching hospital at Bangalore, India. Children presenting with late-onset developmental regression (>6 years) with neurotypical development before regression were studied. Ten children fulfilling the eligibility criteria were identified over a period of 5 years (January 2019 to December 2023). Nine out of ten children were evaluated and treated as in-patients, and were prospectively followed up at 1, 3 and 6 months and 1 year since initial presentation. We reviewed the medical records to collect clinical details, evaluation, prospective clinical follow-up of developmental trajectory, course and outcome. This is a case series, based on hospital record review.

Ethics statement and approval

The study was approved by the Institute Review Board (IRB) of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (approval number NIMHANS/IEC (BEH. SC.DIV.) 2024) (IRB proposal and approval: see Supplementary Files 1 and 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.840) for preparing this case series using information available exclusively from clinical records stored at the hospital. Informed consent was obtained from parents of all children who were part of this study. Written informed consent was obtained from four participants and verbal consent was obtained from the remaining six participants, which was witnessed and formally recorded (informed consent form: Supplementary File 3). Given the nature of illness, the children were not in a position to provide informed assent (IRB approval: Supplementary File 2)

Our sample included six males and four females, with a mean age of 8.3 (s.d. 1.7) years. Mean age at regression was 7.65 (s.d. 1.5) years (range: 6–9.5) and mean illness duration was 10.1 (s.d. 8.5) months (range: 1–24). All children were comprehensively evaluated by paediatric neurologists, and possible organic causes were ruled out through extensive investigations (Table 2). None of the children had motor regression, seizures, abnormal neurological signs or sensory impairment, as per clinical evaluation.

Ascertainment of developmental regression was done through the following methods (a) parent report of pre-regression developmental competencies and corroborative information from extended family members and school teachers; (b) serial observation of developmental competencies; (c) a comparative assessment of socio-adaptive functioning pre-regression, after the onset of regression and at follow-up time points; and (d) pre-regression videos of play and dyadic interaction of the child for supportive information regarding the pre-regression developmental competencies.Reference Furley, Mehra, Goin-Kochel, Fahey, Hunter and Williams4

Results

Case descriptions

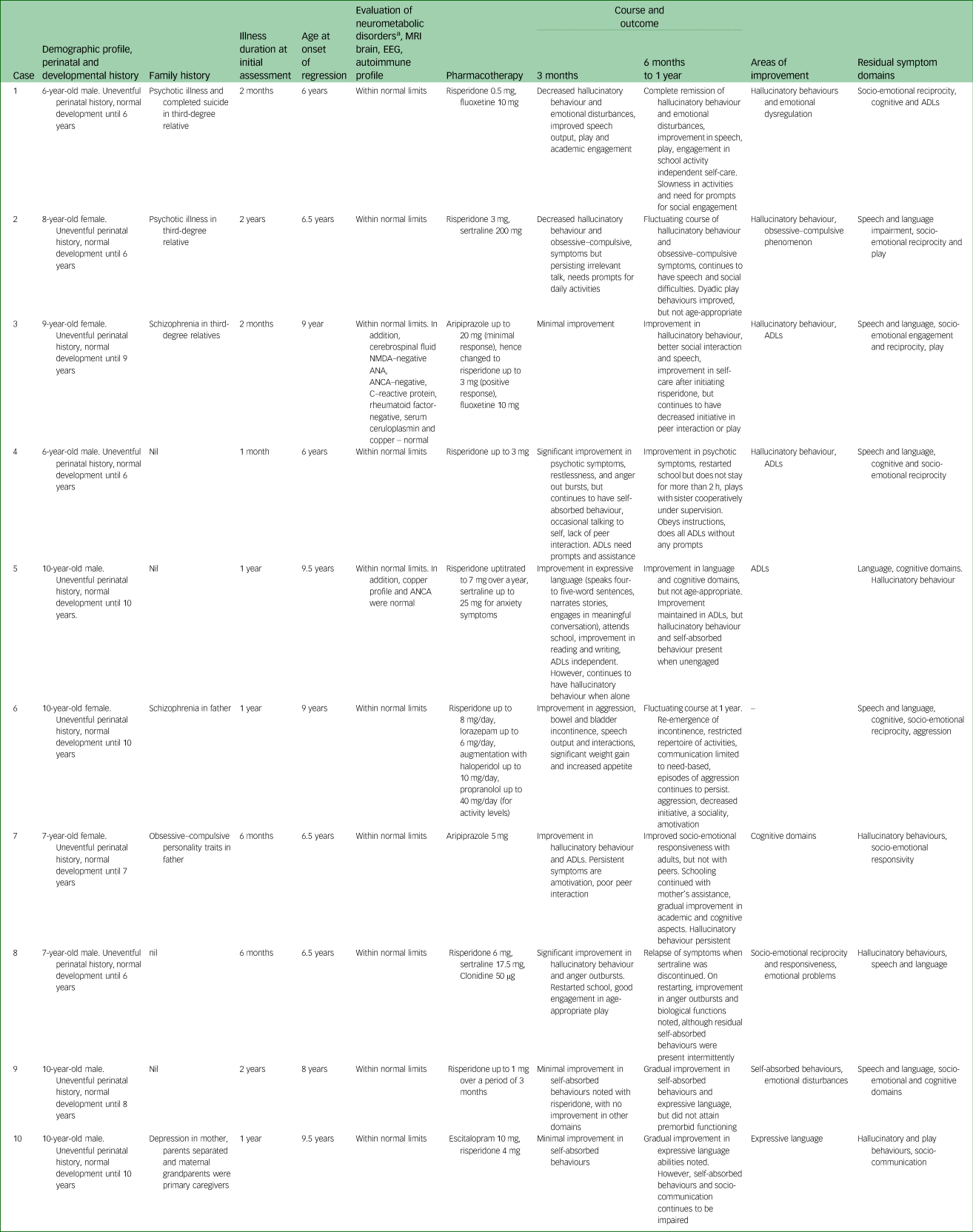

Details of clinical histories and initial presentations are described below. Phenomenological indicators (Table 1) (Fig. 1), treatment details, course and outcome, laboratory and neuroimaging investigations (Table 2) are tabulated. All children had uneventful perinatal history, typical neurodevelopment and had attained age-appropriate milestones before illness onset.

Table 1 Comparison of phenomenology and symptom dimensions of the ten cases

+, present; −, absent; +/−, cannot be commented on.

a. No incontinence but needed prompts and assistance for all activities of daily living, from being independent in activities of daily living before illness onset.

b. Obsessive–compulsive disorder was diagnosed with reasonable certainty only in one case.

Fig. 1 Diagnostic conundrum of developmental regression in children. CDD, childhood disintegrative disorder.

Table 2 Clinical profile, biochemical and neuroimaging investigations, course and outcome

Autoimmune encephalitis panel: anti-NMDA, anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor; anti-AMPA1s 1 and 2, anti-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors 1 and 2; CASPR C, contact associated protein 2-CASPR; VGKC, voltage-gated potassium channel associated, Leucine rich glioma – inactivated protein 1/VGKC associated; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid B1, B2 antibodies. Anti-nuclear antibodies profile (ANA profile): p-ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies – perinuclear; c-ANCA, cytoplasmic; nRNP-sm, small ribonucleoprotein antibodies, Sm, SS-A, SS-B, Scl-70, PM-Scl 100, Jo-1; CENP B, centromere protein; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; dsDNA, nucleosomes, histones, ribosomal P – protein; AMA M2, antimitochondrial antibodies. No epileptiform abnormalities were noted on the EEG. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; EEG, electroencephalogram; ADL, activities of daily living.

a. Neurometabolic blood work up includes the following list of biochemical investigations: urine screen for abnormal metabolites (ferric chloride test, DNPH test, cyanide nitroprusside test, Benedict's test, spot test for mucopolysaccharidoses), tandem mass spectrometry for blood amino acids, free carnitine, short-, medium- and long-chain acylcarnitine (glycine, alanine, valine, leucine/isoleucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, methionine, citrulline, ornithine, arginine, proline, glutamine/lysine, glutamic acid, carnitine panel, free carnitine, C0, Acetylcarnitine, C2, Propionylcarnitine, C3, Malonylcarnitine/3-OH-butyrylcarnitine, C3DC/C4-OH, Butyrylcarnitine, C4, Methylmalonylcarnitine/ 3-OH-isovalerylcarnitine, C4DC/C5-OH, Isovaleryl/2-methylbutyrylcarnitine, C5, Tiglylcarnitine, C5:1,Glutarylcarnitine/3-OH-hexanoylcarnitine, C5-DC/C6OH, Hexanoylcarnitine, C6, Adipylcarnitine, C6DC, Octanoylcarnitine, C8, Octenoylcarnitine, C8:1, Decanoylcarnitine, C10, Decenoylcarnitine, C10:1, Decadienoylcarnitine, C10:2, Dodecanoylcarnitine, C12, Dodecenoylcarnitine, C12:1, Tetradecanoylcarnitine, C14, Tetradecenoylcarnitine, C14:1, Tetradecadienoylcarnitine, C14:2, 3-OH-tetradecanoylcarnitine, C14-OH), plasma lactate, ammonia, homocysteine, vitamin B12, aryl sulfatase and hemogram.

Case 1

A 6-year-old boy presented with a 3-month history of subacute onset characterised by decreased speech and interaction, decreased normative play and apparent loss of pre-existing ability to read or write. Brief periods of talking to self, irritability, crying spells and fearfulness without any apparent triggers, along with intermittent repetitive behaviours like touching ears, licking lips and insisting things be placed in a particular manner, were noted. He required assistance for previously independent activities such as toileting, bathing and feeding. There was a family history of psychotic illness and suicide in a third-degree relative.

Case 2

An 8-year-old girl presented with a 2-year history of subacute onset, progressive course characterised by decreased interaction and self-absorbed behaviour, followed by disorganised behaviours like disrobing herself, urinating and defecating at inappropriate places and chewing non-edible items. There was decreased meaningful interactions and cognitive abilities noted. Repeated hand washing, arranging her possessions in specific patterns, not allowing anyone to touch her belongings, and anger outbursts and aggression on non-adherence was noted in the later course. Bowel and bladder incontinence persisted for a predominant period of the illness course.

Case 3

A 9-year-old girl with well-adjusted pre-regression adaptive functioning except for minor difficulties in academics, presented with subacute onset, continuous course of fearfulness, crying spells and clinging to mother, followed by self-absorbed behaviour. There was loss of contextual and meaningful speech. Occasionally, she would utter the word ‘snake’ and point at her stomach, and was guarded about anyone touching her abdomen. There was further decline in her academic abilities and she needed assistance for all of her self-care activities, including toileting. She also engaged in certain repetitive behaviours like tugging on her skirt repeatedly, or repeated pacing about. There was a family history of schizophrenia in a third-degree relative.

Case 4

A 7-year-old boy presented with subacute onset of talking and smiling to self and decreased interaction with family members, and fearfulness resulting in unprovoked aggression toward the family members for the past month. He also had certain repetitive behaviour like pouring water on his head multiple times intermittently. It was associated with loss of functional speech and play, decline in academics abilities and need for complete assistance for toileting, dressing and bathing activities.

Case 5

A 10-year-old boy with mild language delay with catch up at age 5 years, presented with a 1-year history of insidious onset of decreased speech and language use associated with decreased cognitive abilities. He was found to be mostly self-absorbed, with significant reduction in both expressive and receptive language abilities almost amounting to being non-verbal. He also had decreased socio-emotional reciprocity, with increased engagement in stereotypical and self-absorbed play. There were occasional episodes of crying spells, and clinging to mother. He was completely dependent for his dressing and feeding needs, and toileting indicative of bowel and bladder incontinence. There was a history of cerebral palsy in a sibling.

Case 6

A 10-year-old girl presented with a 1-year history of insidious onset, progressive course characterised by initial obsessive–compulsive symptoms and fearfulness, followed by progressive social withdrawal, and decline in speech to only a few words and need-based communication. Bowel and bladder incontinence, and decreased self-care, evolved during the illness course. She had fleeting eye contact and often engaged in odd non-purposeful behaviours, stereotypic movements and utilisation behaviours. Unprovoked aggression and increased activity levels were noted since illness onset. There was a family history of schizophrenia in the father.

Case 7

A 7-year-old girl presented with insidious onset of loss of previously attained social and speech milestones over 6 months, along with poor eye contact, poor response to name call and not verbalising/indicating for her basic needs. She was noted to have decline in peer interactions and predominantly displayed restricted and non-functional play, with no meaningful engagement in other activities. She also had bowel and bladder incontinence over the illness course.

Case 8

A 6-year-old boy presented with insidious onset of loss of attained milestones in speech, social and cognitive domains. He was noted to be self-muttering with brief utterances about dinosaurs, cartoon characters or ghosts, with no further elaboration. He was also noted to have multiple stereotypical behaviours with no engagement in meaningful play, reading or writing activities. There was associated increased activity levels, sleep disturbances and contextual anger outbursts. Bowel and bladder incontinence evolved during the later course of illness.

Case 9

A 10-year-old boy presented with a 2-year history of insidious onset, characterised by regression of attained milestones in the language and social domains, fearfulness and crying spells. He would make brief utterances and incomprehensible sounds. Play engagement was inconsistent and rarely functional. Non-targeted motoric hyperactivity was noted. There is history of exposure to conflicts and physical abuse between parents from formative years.

Case 10

A 10-year-old boy presented with a 1-year duration of subacute onset of reduction in socio-communication and language amounting to almost mutism. He was noted to have atypical use of non-verbal gestures and play behaviours that were stereotypical and non-functional. Cognitive decline was evident as he could not engage in foundational academics, whereas he was above-average in grade 5 before illness onset. There was a history of parental separation and depression in his mother. There was no bowel or bladder incontinence noted.

Discussion

All ten children presented with similar profiles of developmental regression in speech, social and cognitive milestones, and loss of adaptive skills.

Is this autistic regression?

The onset of developmental regression was after 6 years of age, which was unlike that observed in autism.Reference Matson and Kozlowski17,Reference Barger, Campbell and McDonough18 Two regression patterns have been described in ASD, one initially exhibiting typical socio-communicative development followed by gradual regression over the first 2 years of life, and a second pattern involving socio-communication deficits before the regression.Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21 Some longitudinal studies have reported ASD being acquired at a later age; however, it must be noted that this cohort was referred for developmental concerns at an earlier age, but only at a later date were they formally diagnosed with ASD, representing late diagnosis rather than late onset.Reference Elias and Lord26 The cases in the current study had typical development before the onset, later age at onset of regression and involved broader domains than typically seen in ASD, such as loss of adaptive skills and socio-emotional, language and cognitive regression, thus ruling out the possibility of ASD.Reference Volkmar and Cohen25,Reference Creten, van der Zwaan, Blankespoor, Maatkamp, Klinkenberg and van Kranen-Mastenbroek27,Reference Honjo28

Do the symptom dimensions point toward a diagnosis of COS or severe depression?

All children presented with subacute/insidious onset of developmental regression and had symptoms suggestive of hallucinatory experiences at some point during the disease course. The interpretation of hallucinatory experiences was made based on serial behavioural observations. Eight children were noted to have repetitive utterances (incomprehensible phrases, names of cartoon characters), gesturing or engaging in stereotypical or non-purposeful play. Since hallucinations are symptoms elicited based on internal experiences, it becomes difficult to reliably diagnose this in young children, especially when they also have regression in socio-communication.Reference Adhikari, Ghane, Ascencio, Abrego and Aedma29 Similarly, thought phenomena (including delusions and depressive cognitions) could not be elicited with certainty in any of our cases.

It may be challenging to delineate the psychotic phenomenon (disorganisation/hallucinations) from ritualistic or repetitive behaviours noted in ASD or CDD. ‘Disorganisation’ of thought and behaviour is one of the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia as per the DSM-5.30 Disorganised thinking refers to fragmented or incoherent speech, jumping from one idea to another without logical connections and neologisms, and disorganised behaviour refers to bizarre and unexplained behaviour, including disorganisation in carrying out routine activities.Reference Liddle31 Rather than disorganisation of thought and speech and psychomotor retardation seen in depression and catatonia, actual loss of functional speech associated with atypicality in socio-emotional reciprocity, and not a mere decrease, was noted in all cases. All ten children, exhibited self-absorbed behaviours associated with decreased ability to speak and comprehend, and all of them had gross loss of independence in carrying out their daily activities. These behaviours may be conceptually considered ‘disorganised behaviours’ or ‘psychomotor retardation’ under the diagnostic criteria, but phenomenologically also represent regression or loss of skills and milestones the child had previously attained.

Loss of previously acquired bowel and bladder control has been reported in about 75% of cases of CDD across multiple cohorts,Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21,Reference Rosman and Bergia24 and was present in eight out of ten of our cases. Whether this behaviour is a result of loss of previously attained milestones or the result of a new-onset psychotic phenomenon is only a matter of speculation. Some literature hints at a potential link between urinary incontinence in the initial episode of psychosis and the negative symptom dimension of schizophrenia, indicating a possible connection to underlying prefrontal cortical dysfunction. However, there is currently no definitive evidence establishing this association.Reference Hollis32

Several researchers in the past have reported the diagnostic dilemma in differentiating late-onset autism, CDD and COS.Reference Creten, van der Zwaan, Blankespoor, Maatkamp, Klinkenberg and van Kranen-Mastenbroek27,Reference Honjo28 These diagnostic entities often follow a somewhat similar course, i.e. initial neurotypical development, followed by a sudden deterioration of socio-communication skills, which may be combined with a decline in cognition, intelligence and abilities to independently carry out developmental tasks.Reference Creten, van der Zwaan, Blankespoor, Maatkamp, Klinkenberg and van Kranen-Mastenbroek27 Similar neuropsychiatric presentations may be seen in disorders such as anti-NMDA encephalitis, and neurometabolic and certain neurodegenerative disorders. Social withdrawal, hallucinatory behaviours, emotional and behavioural symptoms like anger outbursts, screaming, fearfulness associated with speech and/or movement disturbance might be one of the initial presentations in anti-NMDA encephalitis.Reference Basheer, Nagappa, Mahadevan, Bindu, Taly and Girimaji33 In the current study, all ten children were evaluated by paediatric neurologists, and neurological causes such as inborn errors of metabolism, storage disorders, epilepsy, structural pathology of the central nervous system and autoimmune encephalitis were ruled out (Table 2). None of the children had seizures, focal/abnormal neurological signs or sensory impairment, as per comprehensive clinical evaluation.

Children were empirically initiated on atypical antipsychotics, as possible psychotic phenomenon were present in all cases. There was improvement in self-muttering and social engagement. Few children responded with an antipsychotic dose of <0.5–3 mg of risperidone (cases 1, 2 and 4), one child needed to switch antipsychotics (case 3) and one needed a combination of psychotropics owing to minimal response with one antipsychotic (case 6). The rationale for pharmacotherapy was largely symptom-targeted, addressing fearfulness, aggression and possible hallucinations. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were considered in six patients, with the target symptom domains being anxiety and repetitive behaviours. For one child (case 3), a diagnosis of obsessive–compulsive disorder could be considered with certainty, because of repetitive behaviours predominantly in the context of repeated hand washing and preoccupations with cleanliness. The dose titration was done gradually, with careful monitoring for response and emerging side-effects. Most children tolerated the antipsychotic dose well. Flat affect, lethargy and incontinence were noted at presentation, before initiation of medications, and some of these symptoms in fact improved with antipsychotic treatment. Extrapyramidal symptoms when present were treated with anticholinergic or dose reduction of antipsychotics as required.

Interventions and outcomes

Irrespective of the diagnostic conundrum, the interventions were formulated from a developmental lens, using principles of naturalistic developmental behavioural interventions, with active parental involvement as ‘co-therapists’ in skill building and retraining.Reference Schreibman, Dawson, Stahmer, Landa, Rogers and McGee34 The impact of regression on parental stress and coping was intense. A multidisciplinary team provided supportive interventions to address parental stress and to encourage continued engagement in therapeutic interventions.Reference Furley, Mehra, Goin-Kochel, Fahey, Hunter and Williams4 Initiating developmentally appropriate activities was extremely important.Reference Furley, Mehra, Goin-Kochel, Fahey, Hunter and Williams4,Reference Mehra, Sil, Hedderly, Kyriakopoulos, Lim and Turnbull21 Developmentally appropriate tasks were reintroduced through play and structured activities, and graded re-entry to school was planned based on developmental readiness.

All children appeared to follow a static course after the period of regression. The response to treatment was gradual over 6 months to 1 year, in the domains of repetitive and hallucinatory behaviours, aggression, irritability and lesser dependence for activities of daily living. Although eight out of ten children presented with loss of bowel/bladder control during peak of the illness course, it resolved as they showed improvement in other domains. Some improvement was noted in speech and language in seven children. Residual symptoms were noted in all children at 1-year follow-up, in the domains of not attaining age-appropriate speech and language, socio-emotional reciprocity and cognitive abilities, and nine out of ten children did not attain pre-regression functioning (Table 2). Similar outcomes were reported in previous studies.Reference Rosman and Bergia24,Reference Volkmar and Cohen25

Developmental regression in the absence of identifiable neurological causes is one of the enigmatic presentations in child psychiatry. Based on longitudinal evaluation of phenomenology, course and outcome at 1 year, COS may be a possible diagnosis for cases 1, 3, 4, 6 and 8; however, the bowel and bladder incontinence preclude the same. Cases 2, 5, 7, 9 and 10 could not be placed under the diagnostic category of schizophrenia, depression or late-onset autism.

Diagnostic conundrums when seen cross-sectionally may be a challenge. In such cases, the child and adolescent mental health clinician's responsibility and immediate aim is to get corroborative evidence for premorbid functioning and extensive aetiological evaluation. For severe manifestations such as developmental regression, where the illness is still evolving, considering CDD as a non-etiological and transitory/tentative diagnosis would aid against premature diagnostic categorisation and provide scope for ongoing aetiological search. Developmental regression cuts across multiple psychiatric and neurological disorders among children. Persistence of deficits in language and socio-emotional development over the course of illness, despite treatment, may raise the possibility of CDD. Over time, children may move out of CDD toward other diagnoses, or may continue to be categorised as CDD if disorganisation and/or loss of acquired skills persist.

To the authors knowledge, this is one of the few large case series with longitudinal follow-up of course and outcome of late-onset developmental regression. Although aetiological work-up was exhaustive, molecular genetics studies and serial neuroimaging could have provided critical information. The team aims to attempt the same at future follow-ups. Irrespective of the diagnostic challenges, transdiagnostic and dimensional framework to interventions is a recommendation for best clinical practice. Long-term longitudinal evaluation is required for these subset of children to understand the transitions in phenomenology, course and outcome, and will provide critical insights on biological underpinnings of developmental regression.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.840

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, H.M., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Shoba Srinath, Former Head and Senior Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; and Dr Satish C. Girimaji, Former Head and Senior Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), for reviewing the manuscript and mentoring support.

Author contributions

S.E.A. contributed to data curation, writing the original draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. S.K.A., P.K. and N.M. were responsible for data curation. R.K.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.M. conceptualised the paper, supervised the drafting of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.