Schizophrenia and stigma

Schizophrenia is the prototypical psychotic disorder and is characterised by the psychotic symptoms of hallucinations, delusions, disorganised speech, grossly disorganised or catatonic behaviour, and negative symptoms.1 Typically, people with schizophrenia suffer from social or occupational dysfunction, such that only a minority will be able to live independently and obtain paid employment.Reference Tandon, Gaebel, Barch, Bustillo, Gur and Heckers2 Nevertheless, around half of those with schizophrenia can be regarded as having a relatively good outcomeReference van Os and Kapur3 and most will derive some benefit from antipsychotic medication.Reference Leucht, Tardy, Komossa, Heres, Kissling and Salanti4

People with schizophrenia face a great deal of stigma, which is defined as a ‘negative attitude (based on prejudice and misinformation) that is triggered by a marker of illness’.Reference Sartorius5 This affects their social life, occupation, self-esteem, confidence and ability to seek help and succeed with treatmentReference Sartorius5. Stigma may even be ‘the main obstacle to the success of programmes to improve mental health’.Reference Sartorius5 For example, young people with schizophrenia are likely to delay seeking treatment because of perceived stigma and the concerns that it would harm their chances of getting jobs, they would not be taken seriously and would be seen as weak.Reference Dockery, Jeffery, Schauman, Williams, Farrelly and Bonnington6 Indeed, the way that members of healthcare teams treat patients with schizophrenia is affected by stigma; for example, in reducing the willingness and confidence of pharmacists to provide medication counselling to people with schizophrenia.Reference O'Reilly, Bell, Kelly and Chen7 Further, people with the diagnosis of schizophrenia often stigmatise themselves in that they regard themselves negatively, and such ‘self-stigma’ is associated with poor neurocognitive function.Reference Chan, Kao, Leung, Hui, Lee and Chang8

Changing the name of schizophrenia

There has been debate as to whether renaming schizophrenia would reduce the negative attitudes expressed about people with the condition. A narrative literature review concluded that the advantages of a name change would outweigh the disadvantages and suggested that an eponym be used,Reference Lasalvia, Penta, Sartorius and Henderson9 although this conclusion was based largely on expert opinion. A recent systematic review found that in countries that have adopted a name change, the results have been inconclusive.Reference Yamaguchi, Mizuno, Ojio, Sawada, Matsunaga and Ando10 The names changed from and to are likely to be important. For example, in Japan, what was called mind-split disease (a literal translation of the Greek origins of the word schizophrenia) was renamed integration disorder.Reference Yamaguchi, Mizuno, Ojio, Sawada, Matsunaga and Ando10 Koike et al Reference Koike, Yamaguchi, Ojio, Shimada, Watanabe and Ando11 found that this name change ‘had a limited effect’, whereas Aoki et al Reference Aoki, Aoki, Goulden, Kasai, Thornicroft and Henderson12 found some improvement in reducing the frequency of reporting an association with violence.

In the English-speaking world, many authorities are beginning to abandon the use of the term schizophrenia both in clinical practice and in the academic literature, and increasingly refer to the condition as psychosis (e.g. Sami et al Reference Sami, Shiers, Latif and Bhattacharyya13). For example, the former Schizophrenia Bulletin recently changed title to Schizophrenia Bulletin: The Journal of Psychoses and Related Disorders in a bid to acknowledge the changing ideas about the diagnosis of schizophrenia.Reference Carpenter14 In 2016, van Os suggested a name changed to psychosis susceptibility syndrome and that the ICD-11 should remove schizophrenia as a term.Reference van Os15 The authors of the British Psychological Society's report Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia debated whether even to use the word schizophrenia in the title of their report.Reference Cooke and Kinderman16, Reference Cooke17 They argued that symptoms of schizophrenia and psychosis are not necessarily mental illness, and labelling all patients who fulfil diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia as having a mental illness can be detrimental and cause more harm than good because of stereotypes and stigmatising views from patients themselves and society. They argue ‘schizophrenia is essentially an idea’ and does not explain the aetiology or likely outcome for a patient.Reference Cooke and Kinderman16 The move to psychosis appears to be based on the assumption that this term will carry less of the negative connotations with severity, chronicity, untreatability and violence associated with schizophrenia. For example, it has been shown that the chances of recovery for a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia (13.5%) may be less than for those who have experienced only first-episode psychosis (38%).Reference Jääskeläinen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha and Isohanni18, Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Stubbs, Cullinane, Murphy and Gaughran19 To our knowledge, this assumption of a reduction in stigma has not been tested. Therefore, we wished to examine if and how the word psychosis and the related term psychotic are used. If it was found that people talk less negatively about psychosis than schizophrenia, it would provide some support for the view that making such a change in official documents, scientific papers and clinical services would reduce stigma.

The role of social media

One way of assessing how different conditions are referred to and discussed is to examine the usage of various terms on social media. Many people use social media as an outlet for opinions and as a resource for information about mental illness.Reference Ashrafi-Rizi and Afshar20 Social media brings people from different parts of the world together for debate and discussion and the dissemination of information, and influence attitudes and health behaviour.Reference Ashrafi-Rizi and Afshar20 Twitter is a micro-blogging platform allowing users to write tweets up to 140 characters in length. On Twitter, one can access a vast amount of data in a limited amount of time, compared with other social media outlets such as Facebook and YouTube, and people's tweets are easily accessible without a reader having an account. Previous studies have investigated how schizophrenia is discussed on Twitter, finding a significant association with negative attitudes and opinions compared with depression and diabetes.Reference Reavley and Pilkington21, Reference Joseph, Tandon, Yang, Duckworth, Torous and Seidman22 However, as far as we are aware, no study has compared how schizophrenia and psychosis are discussed.

Aims

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the use of schizophrenia and psychosis on Twitter and compare the relative proportions of negative use of the two terms. We tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the stigmatisation of psychosis compared with schizophrenia on Twitter.

Method

To identify tweets for the study, Twitter's advanced search tool was used on www.twitter.com to find tweets that contained the words ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘schizophrenic’, and ‘psychosis’ or ‘psychotic’ (we henceforth refer to these as schizophrenia/c and psychosis/tic) and were captured with NCapture (NCapture for Chrome, QSR International, Victoria Australia, available for download at https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/support-overview/downloads#Download-NCapture-and-other-NVivo-add-ons). On NVivo (NVivo 12 for Mac, QSR International, Victoria Australia, available for download at https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/support-overview/downloads#Download-NCapture-and-other-NVivo-add-ons), using an inductive coding method suggested by Reavley and Pilkington,Reference Reavley and Pilkington21 tweets were coded based on the degree and nature of stigma toward schizophrenia/c and psychosis/tic as well as coding for user type and tweet content. Exclusion criteria were as follows:

(a) Lack of context: where the tweet was unable to be understood by the reader or the tweet was a spam tweet with no meaning behind it.

(b) Non-English: where all or the majority of the tweet was not in English.

(c) Repetition: where the tweet was exactly the same as another tweet in the data-set.

(d) Retweet: a reposted or forwarded tweet that was originally posted by another user.

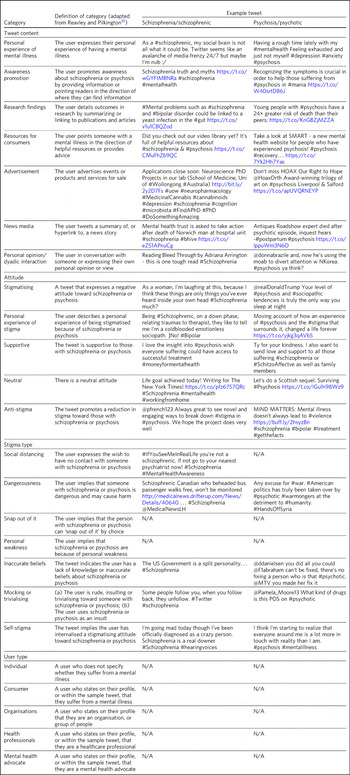

If included, each tweet was coded into three or four categories, as follows:

(a) User type: individual, consumer, health professional, organisation and advocate.

(b) Tweet content: personal experience of mental illness, awareness promotion, research findings, resources for consumers, advertisement, news media and personal opinion/dyadic interaction.

(c) Attitude: stigmatising, personal experience of stigma, supportive, neutral and anti-stigma.

(d) (If category (c) indicated stigma) Stigma type: social distancing, dangerousness, snap out of it, personal weakness, inaccurate beliefs, mocking or trivialising and self-stigma.

G.L.P. and J.E.H. initially coded 100 tweets, using the categories and definitions from Reavley and Pilkington.Reference Reavley and Pilkington21 Any tweets that were hard to categorise were discussed and resolved before J.E.H. and G.L.P. both coded 10% of the identified tweets to confirm the interrater agreement. The overall agreement was 87.6%, illustrating that the coding method had high reliability. G.L.P. then coded all tweets from two 7-day periods: 16–22 April 2017 and 21–28 September 2017.

Fig. 1 Proportion of all tweets coming from each type of Twitter user.

To analyse the data, χ²-tests were manually calculated to compare the proportions of the different types of tweets about schizophrenia/c versus psychosis/tic. These were compared with a χ² table to determine the P-value, with a value of P < 0.05 deemed significant.

We did not seek ethical approval for this study as it concerns the use of previously published material in the public domain.

Fig. 2 The proportion of all tweets in each ‘tweet content’ category.

Fig. 3 The proportion of all tweets in each ‘attitude’ category.

Results

Examples of tweets in each category are shown in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion

The total number of schizophrenia/c tweets over the two 7-day periods was 1120 and the total number of psychosis/tic tweets was 1080 over the two 7-day periods. We excluded 696 (62.1%) schizophrenia tweets and 664 (61.5%) psychosis tweets from the data-set based on the criteria above, leaving 424 (37.9%) schizophrenia tweets and 416 (38.5%) psychosis tweets in the analysis.

For schizophrenia/c, 490 (70.4%) of the excluded tweets were retweets, 157 (22.6%) were repetitions, 27 (3.9%) were excluded because of lack of context and 22 (3.2%) were not in English. For psychosis/tic, 560 (84.3%) were retweets, 78 (11.7%) were repetitions, 15 (2.3%) were excluded because of lack of context and 11 (1.7%) were not in English.

Fig. 4 The percentage of tweets that were stigmatising wtihin each ‘tweet content’ category.

User type

For schizophrenia/c, individuals (n=188, 44.3%) and organisations (n=186, 43.9%) tweeted the most. This was followed by consumers (n=22, 5.2%), health professionals (n=18, 4.2%) and mental health advocates (n=10, 2.4%).

For psychosis/tic, individuals tweeted the most (n=275, 65.9%), followed by organisations (n=108, 25.9%), health professionals (n=28, 6.7%), mental health advocates (n=5, 1.2%) and consumers (n=1, 0.2%).

Tweet content

For schizophrenia/c, the tweets were most commonly personal opinions/dyadic interactions (n=134, 31.5%). This was followed by research findings (n=105, 24.6%), experience of mental illness (n=76, 17.8%), awareness promotion (n=37, 8.7%), advertisement (n=35, 8.2%), news media (n=29, 6.8%) and resources for consumers (n=10, 2.3%).

For psychosis/tic, the majority of tweets were also personal opinion/dyadic interaction (n=234, 56.1%). This was followed by experience of mental illness (n=59, 14.1%), research findings (n=49, 11.8%), advertisement (n=38, 9.1%), awareness promotion (n=20, 4.8%), resources for consumers (n=10, 2.4%) and news media (n=7, 1.7%).

Attitude

For both schizophrenia/c and psychosis/tic most of the tweets were neutral (n=334, 78.6% and n=266, 63.9%, respectively). However, there was a significant difference in the number of stigmatising tweets: 41 (9.6%) of the schizophrenia/c tweets were stigmatising, whereas 131 (31.5%) of psychosis/tic tweets were. χ²-testing revealed a significant difference with a χ² value of 237.03 (1 d.f., P < 0.0001).

For schizophrenia/c, 35 (8.2%) were anti-stigma, 10 (2.4%) were supportive and 5 (1.2%) were recounting a personal experience of stigma. For psychosis/tic, 15 (3.6%) were anti-stigma, 2 (0.5%) were supportive and 2 (0.5%) recounted a personal experience of stigma.

When analysing the stigmatising tweets, it was found that for schizophrenia/c, 35 (85.4%) came from individuals, 5 (12.2%) came from organisations and 1 (2.4%) came from a consumer. The vast majority of the stigmatising schizophrenia/c tweets were personal opinions/dyadic interactions (n=33, 80.5%). Six (14.6%) were from news media and two (4.9%) were about experience of mental illness.

In the stigmatised psychosis/tic tweets, 123 (94.6%) came from individuals and 5 (3.8%) came from organisations. Mental health advocates and consumers made up the other users, each tweeting one (0.8%) of the stigmatising psychosis/tic tweets. Finally, 125 (95.4%) of the stigmatised psychosis/tic tweets were personal opinion/dyadic interaction, 3 (2.3%) were about experience of mental illness, 2 (1.5%) were advertisements and 1 (0.8%) was news media.

For schizophrenia/c, 33 (24.6%) of personal opinions/dyadic interactions were stigmatising and 6 (20.7%) of the news media tweets were stigmatising. Two (2.6%) of the schizophrenia/c tweets about experience of mental illness were stigmatising. For the other categories of tweet content, none of the tweets were stigmatising.

For psychosis/tic, 125 (53.4%) of personal opinions/dyadic interactions were stigmatising. One (14.3%) of news media tweets was stigmatising, two (5.3%) of the advertisement tweets were stigmatising and three (5.1%) of tweets about experience of mental illness were stigmatising. The other categories did not contain any stigmatising tweets. Comparing the percentage of personal opinions/dyadic interactions that were stigmatising demonstrates a statistically significant difference, with a χ² value of 44.65 (1 d.f., P < 0.0001).

Stigma type

Of the stigmatising schizophrenia/c tweets, 22 (53.7%) were mocking or trivialising schizophrenia/c, 10 (24.4%) were categorised as dangerousness, 4 (9.8%) as social distancing, 3 (7.3%) as inaccurate beliefs and 2 (4.9%) as self-stigma.

For psychosis/tic, 93 (69.4%) were categorised as mocking or trivialising, 36 (26.9%) as dangerousness, 3 (2.2%) as inaccurate beliefs and 2 (1.5%) as self-stigma.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess any difference in views expressed about schizophrenia compared with psychosis on Twitter to assess the potential effect of a name change of schizophrenia. We found that the terms psychosis/tic were more commonly included in tweets expressing negative attitudes to these conditions than tweets referring to schizophrenia/c. Most of the stigmatising tweets were tweeted by individuals in the format of personal opinion/dyadic interactions. The most common forms of such stigmatisation were mocking, trivialisation or making associations with dangerousness. For both schizophrenia/c and psychosis/tic, however, the majority of tweets were non-stigmatising and provided potentially useful information, often about new research, normally broadcast by organisations.

Fig. 5 Proportion of ‘stigma type’ in all stigmatising tweets.

Comparisons with previous studies

As far as we are aware, this is the first study to assess attitudes to schizophrenia compared with psychosis on Twitter or any other social medium. However, there are some previous studies that have compared attitudes to schizophrenia and other conditions on Twitter and on other social media. Reavley and PilkingtonReference Reavley and Pilkington21 compared schizophrenia with depression on Twitter and found that there was a significantly greater stigmatisation toward schizophrenia: 5% of the schizophrenia tweets they identified (n = 451) were stigmatising. Joseph et al Reference Joseph, Tandon, Yang, Duckworth, Torous and Seidman22 examined the use and misuse of schizophrenia on Twitter compared with diabetes and found a significantly greater proportion of schizophrenia tweets contained negative attitudes. Approximately one-third of their schizophrenia tweets had negative connotations (n = 685). Our figure of 9.35% (n = 424) falls in between what these two studies found. The difference in the percentage of schizophrenia tweets rated as stigmatising at different times could reflect coding differences but may be because of the effect of short-term changes in discussions about schizophrenia on Twitter.

There is some literature on the stigmatisation of schizophrenia and psychosis in entertainment media. A content analysis of Finnish and Greek videos on YouTube found that 83% of 52 videos portrayed schizophrenia in a negative way.Reference Athanasopoulou, Suni, Hätönen, Apostolakis, Lionis and Välimäki23 Similarly, Nour et al Reference Nour, Nour, Tsatalou and Barrera24 found that most videos presenting schizophrenia on YouTube inaccurately portray the condition. GoodwinReference Goodwin25 examined the stereotyping of characters experiencing psychosis in 33 psychosis-related horror films released before the study was conducted. He concluded that 78.8% portrayed a homicidal maniac and 72.7% portrayed a pathetic or sad character. This is in keeping with our finding that psychosis is heavily stigmatised.

News media are also a focal point for the stigmatisation of mental health conditions. VilhauerReference Vilhauer26 analysed 181 USA newspaper articles mentioning the auditory verbal hallucinations that are diagnostic features of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. They found that about 50% of the articles associated auditory verbal hallucinations with criminal behaviour and violence. These findings are broadly in keeping with a more recent study that concluded that over half of all UK newspaper articles about mental health (n = 200) are negative and 18.5% indicate an association with violence.Reference Chen and Lawrie27

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is its ability to assess peoples’ uncensored views about schizophrenia and psychosis without the need of a survey, the results from which could be affected by social desirability bias. The nature of Twitter means that, once published, a tweet is accessible to anyone without further permission from the tweet's author. Relevant tweets were easy to access on www.twitter.com with the advanced search tool and the process of coding was relatively time-efficient and simple using NVivo.

There are, however, a few limitations of this study. First, capturing data for two arbitrarily chosen 7-day periods means that external events and news cycles may have affected the way people discuss schizophrenia and psychosis, perhaps reducing the generalisability of the data. Of note, there were news stories about USA's response to North Korean nuclear missile testing in the April 2017 observation period,28 and September 2017's period was soon after a bomb injured 30 people in London, England.29 A further study could look in detail about how news media and current affairs influence people's expression of mental illness on social media. A longer period of study could examine detail how current affairs influence people's discussion of mental illness on social media, and potentially highlight trends in how people discuss schizophrenia and psychosis.

Another limitation is that spelling mistakes, abbreviations and colloquial terms for the searched terms may be used in tweets. By searching for only ‘schizophrenia, ‘schizophrenic’, ‘psychosis’ and ‘psychotic’, tweets containing mistakes, abbreviations and colloquial terms will not have been captured in the search. We decided not to include abbreviations and colloquial terms in the search because it may not be clear whether tweets would actually have been about schizophrenia and psychosis. An example would be the abbreviation ‘psycho’, which could refer to psychopath, rather than psychosis. However, if anything, it is more likely that spelling mistakes, abbreviations and colloquial terms may have higher rates of stigmatisation. In a similar vein, future studies could map the different definitions of schizophrenia/c and psychosis/tic used by lay individuals and professionals as this may influence the degree of stigmatising attitudes.

Both the 7-day window convenience sampling and the ability of users to privatise their Twitter accounts could have contributed to selection bias within the study. Content from private accounts would not be visible to our searches, and it would be an interesting but technically challenging study to assess whether private and public accounts have different levels of stigma. Selection bias is an often-encountered issue when conducting research on internet-based communications, and although an attempt to mitigate this was made by analysing all tweets from within the time frame, this may reduce the external validity of the conclusions.Reference Li and Walejko30

Finally, this study only looked on www.twitter.com and there are other social media platforms that could be assessed. Facebook data may be hard to access as the average person is likely to have their profile on a private setting, but it would be interesting to see if psychosis content on YouTube is as negative and inaccurate as it is for schizophrenia. Future work could also compare the stigmatisation of different psychoses on Twitter and other social media.

In conclusion, on Twitter, psychosis is more stigmatised than schizophrenia. This suggests that the term psychosis should not be used if schizophrenia is to be renamed with the aim of reducing stigma. Further, given that different psychotic disorders have particular treatments and varying prognoses,Reference Lawrie, O'Donovan, Saks, Burns and Lieberman31, Reference Lawrie, O'Donovan, Saks, Burns and Lieberman32 such a move to a more generic term may do more harm than good.

About the authors

Giorgianna L. Passerello is a medical student at Edinburgh Medical School, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK. James E. Hazelwood (BMedSci) is a medical student at Edinburgh Medical School, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK. Stephen Lawrie (MD Hons) is Head of Psychiatry at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, University of Edinburgh, UK.

Appendix 1 Table of category definitions and example tweets

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.