Law enforcement officers routinely come into contact with members of the public who have mental health problems. In the UK, estimates of police incidents linked to mental health crises have increased over recent years.Reference Coleman and Cotton1 Within England and Wales, Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 2007 allows police officers to detain people who are experiencing a mental health crisis and who are considered to pose a risk to themselves or others.2 Although this measure may be unavoidable, it is often distressing, expensive and labour-intensive.Reference Riley, Freeman, Laidlaw and Pugh3 In addition, police officers often feel that they lack the training to appropriately support those in mental health crisis.Reference Wells and Schafer4

In response to the increasing use of Section 136, the Department of Health funded several regional pilots of street triage for mental healthcare in 2013.5 Triage models typically involve mental health professionals working in partnership with police officers, providing expertise through a telephone service or an in-person mobile unit.

More services have now been commissioned at a local and regional level by mental health trusts and police forces. The provision of triage services nationally, however, remains unknown and there is a lack of information regarding the operational models used. There is also no systematic information regarding police officer opinions of such services.

Recent changes to the Policing and Crime Act 2017 made it a legal requirement to consult, where practical, with a mental health professional before instigating a Section 136.6 Street triage schemes, whose primary function is to introduce mental health expertise during police incidents, may be ideally placed to do this. As mental health police partnerships become more vital at the point of crisis, information on service models will enable better planning of services to meet the requirements of the legal changes.

Our study aimed to determine the prevalence of mental health street triage services in England and to characterise their operational models. We asked whether services were predominantly mobile- or control room-based, how they were staffed, which vehicles and locations were used, the hours of operation and the reasons cited for use.

Our second aim was to systematically collect the views and experiences of police officers who have used services. We identified how regularly officers had contact with individuals experiencing mental health crises, whether they frequently used Section 136 and their confidence levels when dealing with mental health crises. We also asked whether police officers were aware of local street triage services, their preferences regarding their model and whether they found them beneficial.

Method

Survey design and samples

We conducted two surveys. Data were collected between June and October of 2017, using an online survey tool (www.surveymonkey.com). The first was a cross-sectional survey of all 55 National Health Service (NHS) mental health trusts in England.

The second was a survey of operational police officers in the Thames Valley police force. Thames Valley Police provide police services for 2.1 million people residing in Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. Street triage services have been available in the region since 2013 because of collaboration between Thames Valley Police and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. The street triage service provides telephone support and a co-response mobile unit (where a police officer and mental health worker respond to incidents in a police vehicle) between the hours of 18.00 h and 04.00 h.

Both surveys met Health Research Authority criteria for a service evaluation and were approved by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Procedure

For the NHS trust survey, letters were sent to every trust's Chief Executive. Non-responders were followed up twice when necessary, at 4 and 8 weeks. For the police survey, surveys were emailed to all response police constables and police sergeants employed by Thames Valley Police in September 2017, with responses collected until October 2017. A single reminder was sent out to all officers 2 weeks after the initial request.

Survey questionnaire

The surveys were constructed to address the primary and secondary aims of the project. The surveys took up to 30 min for participants to complete, and were conducted solely online. We collected demographic information and length of service for all respondents. The survey questionnaires are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Results

Identifying and characterising NHS street triage services

Prevalence of street triage services

A total of 40 out of 55 (73%) mental health trusts in England responded to our survey. Of the 40 respondents, 28 (70%) offered street triage services. Of those that had services, the mean length of provision was 2.9 years, with wide variability from 6 months to 5 years of operation. Most areas reported that services had been available for 2–4 years.

Of those that did not provide a service, two (17%) had definite plans for introduction. Seven trusts reported having more than one street triage service, crossing different jurisdictions (police and/or social services) in their geographical area, giving a total of 41 street triage services represented in the survey.

Models of street triage

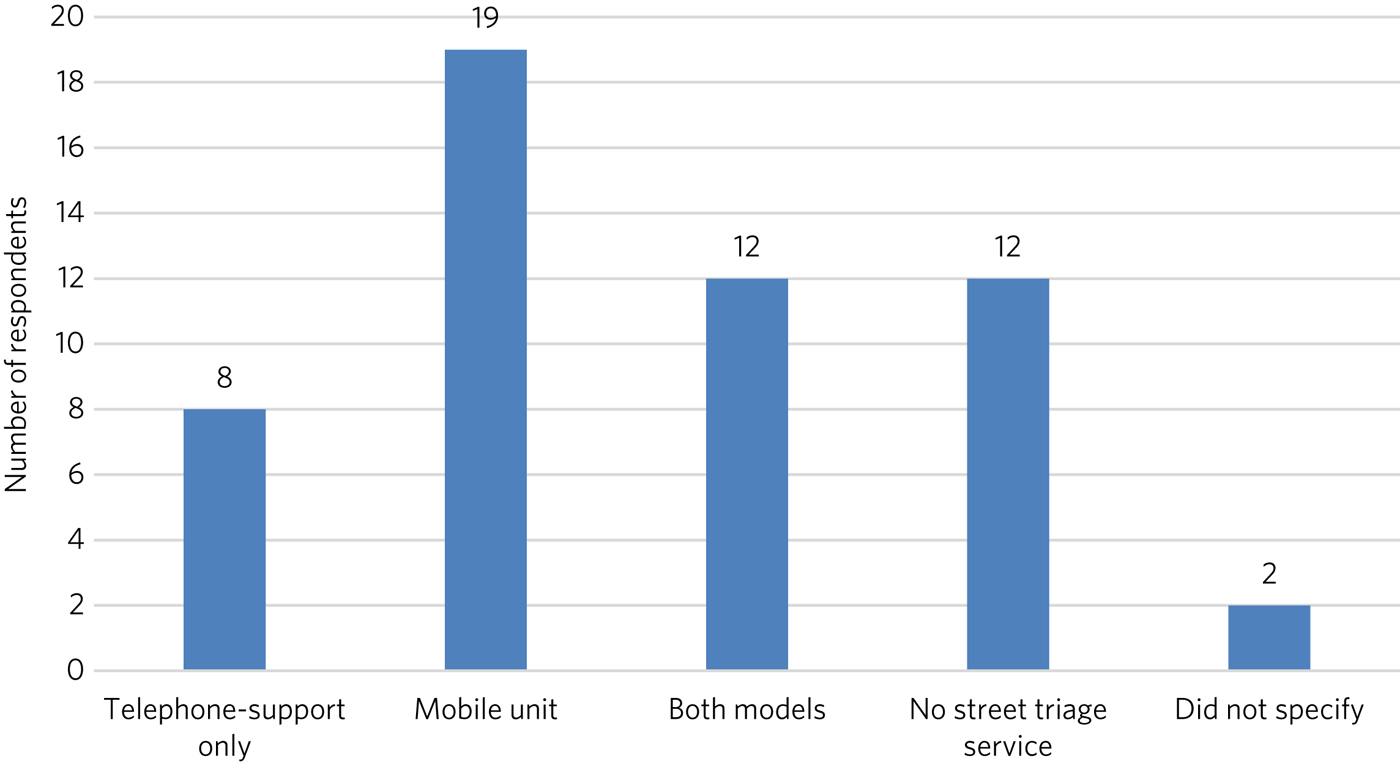

Eight out of 41 (20%) of the services described a telephone support only street triage service, 19 (46%) reported a mobile unit and 12 (29%) reported they had both means of response (Fig. 1). Two respondents (5%) did not specify.

Fig. 1 Reported frequencies of models of triage.

Staffing

A total of 28 out of 36 respondents (78%) reported their service was staffed by police officers and mental health staff, and eight out of 36 (22%) reported it was staffed by mental health staff only (a model in which mental health staff provide telephone support or attend police incidents after a referral from the police at the incident).

Services were overwhelmingly led by health staff (27 out of 41; 82.5%), although several services had police officers as lead (five out of 41; 12.5%) or a combined leadership model (six out of 41; 12.5%). One of the services (5%) did not have a designated lead. Two respondents (5%) did not specify. On average, there were 2.05 whole-time equivalent staff on duty per shift.

Vehicle and location

Of the 31 reported mobile services, ten (32%) used marked and 11 (36%) used unmarked police vehicles. Four (13%) used personal vehicles or ambulances and six (19%) respondents reported that they used a combination.

A total of 38 services reported on their main location for street triage services, with 28 (74%) services located at police stations and ten (26%) located at mental health sites.

Hours and days of operation

There was a wide range of reported hours and days of operation. Only three of the 28 trusts (11%) offered 24/7 availability, with the majority (79%) typically only providing night shifts (usually between late afternoon or early evening and a few hours past midnight).

Methods of contact

Street triage teams were contacted in a variety of ways, including 999 emergency operators (10%) and from the police control room (18%). The most common method, however, was a combination of means (72%), including 999 calls, control room, individual police officers and other emergency services.

Reasons cited for service use

Service providers gave a number of reasons for street triage call-outs: 98% (39 out of 41) reported that call-outs had been made for cases of self-harm and there were also high figures for other reasons, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Reasons cited for use of street triage

a. Percentages do not add up to 100% because of multiple responses per question.

The views and experiences of police officers regarding street triage services

Demographic information

The police survey was sent out to 579 officers, of whom 264 responded, for a response rate of 45.6%. Table 2 presents service and demographic results of respondents.

Table 2 Demographic and service characteristics of police survey respondents (n = 264)

Mental health training

A total of 207 out of 256 (81%) of respondents reported they had received formal mental health training in the past 3 years, often in more than one form. Eight respondents did not respond. This training was generally mandated (181 out of 221 respondents; 82%).

Contact with mental health crises

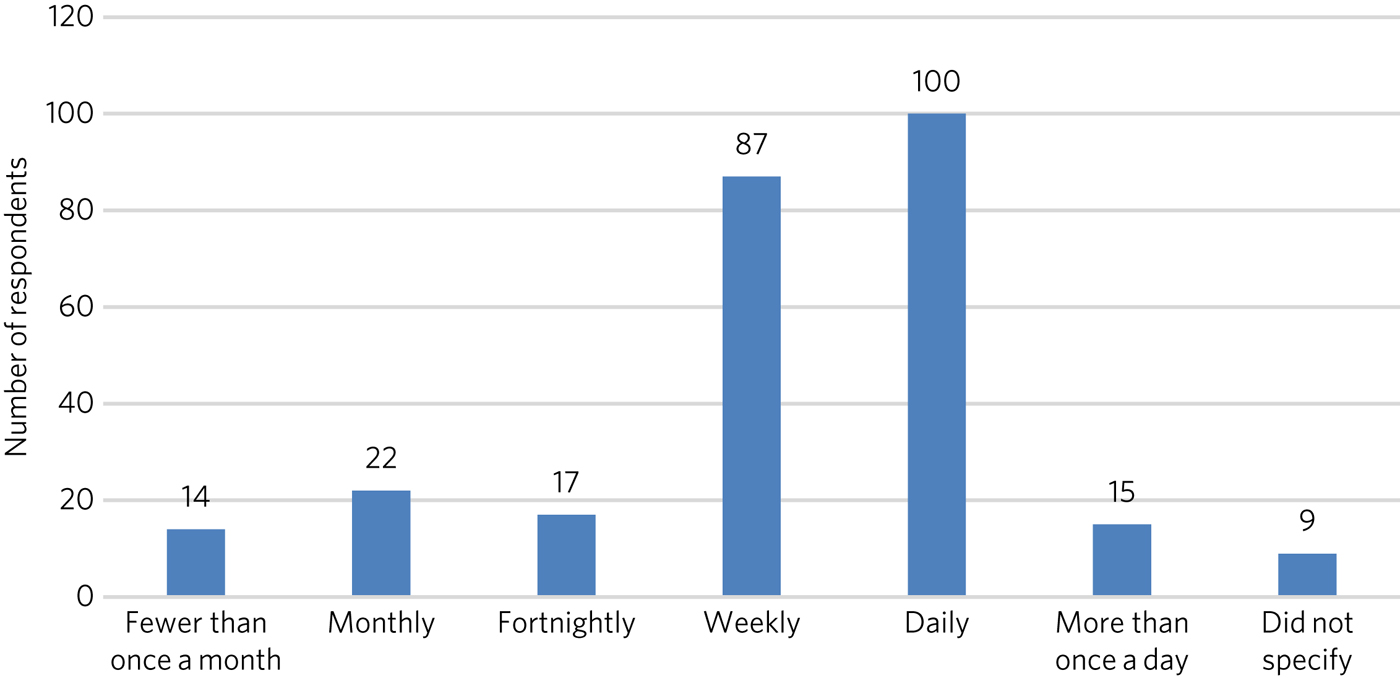

A total of 87% (222 out of 255) of respondents reported regular (approximately every shift) face-to-face contact with the public, with 79% (202 out of 255) reporting weekly or more frequent contact with people in mental health crises; within this subset, 115 (45%) reported daily or more frequent contact (Fig. 2). Respondents reported that on average, four out of their past ten incidents involved mental health crises.

Fig. 2 Frequency of contact with members of the public with mental health problems.

Officers' confidence regarding mental health incidence varied: 71% (178 out of 252) reported they were at least fairly confident, whereas 10% (25 out of 252) described themselves as unconfident.

Awareness and use of street triage

Levels of awareness of the service were high at 97% (249 out of 256): 92% of respondents who answered this question had used street triage (234 out of 257) and 92% of these respondents described the triage service as helpful. Sixty per cent (145 out of 245) had used both mobile units and telephone support.

Respondents were further asked for their experiences of and preferences for the two systems. There was a clear preference for response in person, with 47% (68 out of 145) reporting this as being more helpful and only one respondent feeding back that telephone support was better. The remainder (52%; 76 out of 145) reported that both were equally helpful. A total of 98% of respondents (240 out of 245) overall felt that the service has been beneficial in the Thames Valley area and 71% (173 out of 245 respondents) felt that it should be available 24 hours a day.

Use of Section 136 and interactions with street triage

More than half of respondents had used Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 2007 (58%; 146 out of 251) and only 52% of those using the powers (76 out of 146) had involved the street triage service in the process. The most common reason cited was the unavailability of the street triage service because of hours of operation or other demands on it (83%; 58 out of 70).

Officers' free-text responses and feedback

Sixty respondents made comments in the free-text section, with 58 (98%) commenting that the service was highly beneficial. Officers noted that the service was ‘long overdue’ and ‘one of the best decisions made by Thames Valley Police and NHS in recent years’. One officer directly commented on its necessity: ‘[Mental health] is a specialist area and police officers are not mental health specialists’. Additional reported benefits included saving police time and reducing stigma.

Many stated that they wished that the service was available 24/7 or at least extended hours. One officer wrote ‘the only downside is that it is not already a 24-h service’. Additional comments referenced the lack of availability of child mental health workers and social workers, as ‘[police officers] seem to come across a lot of younger people with mental health issues too’.

Discussion

These surveys are the first attempt to characterise street triage services nationally since the launch of the pilot projects in 2013, and to get a detailed snapshot of police attitudes toward them. It is clear that street triage services, although still a relatively new model of care, are now widespread across England. They have continued to expand in spread and scope since their introduction, understandably given the increasing contact between police officers and those with mental illness. This is also reflected in the changes to the Policing and Crime Act, which will necessitate better police–mental health interagency collaboration;6 street triage is best prepared to fill this gap in service.

Our National NHS survey highlights significant variations in street triage models. Hours of operation vary, although usually with an emphasis on evenings, night-times and weekends, with little or no cover during the daytime. Levels of investment vary substantially and are reflected in staffing numbers and types of model; a mobile in-person response is inevitably initially costlier than telephone support. However, the former service is more valued by officers and may be more effective at freeing up police time and allowing for appropriate interventions, and as a result may be more cost-effective. We simply do not know. Future research must concentrate on what the effective elements of street triage are that improve patient experience, reduce ‘wasted’ police time and improve outcome in terms of health use, functioning and criminal justice interactions.

Most services are located on police premises, but are led by NHS staff. This may be appropriate in the short-term, but there needs to be consideration of whether a merger of personnel would be more effective. There is similar lack of clarity in many funding models, with the key question being ‘who should pay for these services?’. We did not specifically explore this in our study, but opinions seem to differ between the three main agencies concerned (the police, health and social care). A hybrid funding model involving the interested parties would likely be most appropriate but this requires negotiation and thought; in these austere times this will not be easy. Future work to determine how to best navigate such financial and institutional barriers to interagency cooperation between the police and health sector is needed.

Police officers from our survey are overwhelmingly supportive of street triage. There was a clear preference for services to exist and to be provided in-person. There was strong support for 24/7 services. There was a high frequency of responding to mental health incidents described by participants, supporting the view that mental health work is now ‘core police business’.Reference Adebowale7 This underpins the need for triage services, heightened by recent changes to legislation that require officers to seek qualified mental health advice before using Section 136, rather than seeking guidance retrospectively.6 As mental health crises occur at any time of the day, it was not surprising that the majority of officers in our survey believed that street triage should be available 24/7. Longer hours of operation, more integration and a higher profile may help to improve the training and confidence of officers.Reference Reveruzzi and Pilling8 We do not know whether face-to-face triage is more effective than telephone triage. Only one previous study has compared these models.Reference Jenkins9 Their analysis suggested that a face-to-face model can reduce the overall use of Section 136 and increase the proportion resulting in hospital admission, while the telephone-only service did not.

Limitations

Both surveys may include some selection bias, in common with any survey of this type. However, the respondents in our police survey were fairly large in number, there was a reasonable response rate and they appear representative. Our national NHS survey achieved an excellent response rate of 73%, unusually high for such a survey and likely to be protective against selection bias.

Implications

In conclusion, street triage services are widespread across England and increasingly seen as a permanent part of our response to mental health crises. Despite this, models vary significantly and there is little or no evidence on which to base good practice or commissioning decisions. Outcome data is almost non-existent. Our surveys show a clear appetite for services to exist and to be strengthened. Recent changes to the Police and Crime Act will almost certainly stimulate this, with officers being required to seek advice in real time. Public concerns regarding civil liberties and the unacceptable cases of people being stranded in police cells while arrangements are made also make the case that mental health expertise during these crises is vital.

However, the increase in use of street triage will require greater resources and further investment. Questions should be asked as to how services can be organised most effectively and efficiently and how they can most benefit those experiencing mental health crises. Evidence is urgently needed regarding the effects of street triage services and, crucially, what elements of the service are effective in reducing risk and improving outcome. Future studies could also investigate mental health staff or patients' perceptions regarding the quality of triage care.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (grant number BZR00180). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

About the authors

Abirami Kirubarajan is a Medical Student at the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine, Canada. Stephen Puntis is a National Institute for Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellow at University of Oxford, Warneford Hospital, UK. Devon Perfect is an Assistant Psychologist at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Warneford Hospital, UK. Marc Tarbit is Chief Inspector of Thames Valley Police at St Aldates Police Station, UK. Mary Buckman is Head of Social Care for Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Warneford Hospital, UK. Andrew Molodynski is a Consultant Psychiatrist with Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Warneford Hospital, UK.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.