Sleep is a behaviour found throughout the animal kingdom and it occupies approximately a third of our lives. The preservation of this vulnerable state attests to its importance, yet we still do not fully understand its functions and mechanisms. Yet anyone who has experienced a sleep disorder will confirm how important good sleep is to health and quality of life. This is particularly true in mental healthcare, where poor sleep is a significant concern for many patients. It is likely that many people with sleep disorders will present to psychiatric services rather than sleep clinics and so it is essential that mental health workers are aware of these disorders and able to recognise them.

In this article we look at the six major categories of sleep disorder as defined in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3; American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). The categories are:

• sleep-related breathing disorders

• central disorders of hypersomnolence

• parasomnias

• sleep-related movement disorders

• circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders

• insomnia.

This article is not intended to be a detailed examination of these disorders, but rather a broad overview of the field designed to raise awareness of this vital and fascinating area.

Sleep-related breathing disorders

What are they?

Although there are several sleep-related breathing disorders the one most likely to be encountered in psychiatric practice is obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). This is the repeated collapse of the pharyngeal portion of the airway during sleep, leading to partial or complete obstruction of the airway. This in turn leads to the restriction or cessation of airflow. Unlike central sleep apnoea, where respiration ceases because of a reduction in respiratory effort, the respiratory effort in OSA is maintained. The cessation of airflow can result in significant oxygen desaturation and is physiologically stressful. Ultimately, the apnoea will lead to an arousal when the patient will reopen their airway. As a result, sleep is disrupted by multiple stressful physiological events and multiple arousals. This usually (but not invariably) results in excessive daytime sleepiness and increased risk for numerous medical conditions, including hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes and stroke (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014).

Diagnosis and screening

Often the first clue that a patient may have OSA is excessive daytime sleepiness. This can be measured quantitatively using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which asks patients about their likelihood of falling asleep in eight scenarios. Although there is some debate about the exact cut-off between normal and pathological sleepiness, a score of 10–11 or above is considered indicative of excessive sleepiness. People with OSA are likely to be prolific snorers, although this is not always the case. They may report choking in their sleep or a bed partner may notice the apnoeas. OSA is more common in overweight individuals with thick necks or retrognathia and is more common with advancing age (Greenberg Reference Greenberg, Lakticova, Scharf, Kryger, Roth and Dement2017).

Screening for OSA has become much cheaper and easier in recent years. Oximetry performed in the home is now widely used as an initial screening tool and often this is sufficient to make the diagnosis. However, there are times when a more detailed respiratory study, which monitors respiratory effort and airflow in addition to oxygen saturation levels, or a full polysomnogram may be warranted. OSA is diagnosed if there are at least 15 obstructive respiratory events an hour. It is also diagnosed if there are more than five events an hour in the presence of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, observed or subjective apnoeas, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, insomnia, cognitive dysfunction or a mood disorder (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014).

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

The fact that insomnia, cognitive dysfunction and mood disorders are among the diagnostic criteria for OSA gives an indication of the possible causative role of OSA in these disorders in some people. Cognitive impairment is a common finding in OSA. Some of this impairment is due to the direct effects of sleep disruption, but some of it is due to the hypoxic damage to the hippocampus and other structures. Surprisingly, at least some of this damage may be reversible with effective treatment of the OSA (Canessa Reference Canessa, Castronovo and Cappa2011).

Cross-sectional studies have shown that depression is significantly more common in people with OSA. Although we do not know with certainty that OSA has a causative role in depression, given that 20–40% of people with OSA have depression (Harris Reference Harris, Glozier and Ratnavadivel2009), it is clearly vital to screen OSA patients for depression. It is not yet possible to say whether treating OSA improves depression (Harris Reference Harris, Glozier and Ratnavadivel2009).

Finally, given the propensity for many psychiatric drugs to cause weight gain, it is likely that many patients taking these medications will develop OSA as they put on weight. It is therefore important for psychiatrists to be vigilant for signs of OSA and to ask about these signs repeatedly over the years, particularly as increasing age is also risk factor for OSA.

Treatment

If weight is thought to be a factor, then weight loss may be curative. However, this is often very difficult, particularly for patients who are already tired and sleepy! In mild to moderate OSA a mandibular advancement splint, an intraoral device which advances the lower jaw, thus widening the airway, can be effective. However, for more severe cases the gold standard remains continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (Epstein Reference Epstein, Kristo and Strollo2009). CPAP involves sleeping with a mask that covers the nose or nose and mouth; a small air pump increases the air pressure within the mask so that the inspired air is at a higher pressure than the air in the room and this holds the airway open. Despite its efficacy, adherence is a problem with CPAP, often because of discomfort and claustrophobia. There is an increasing role for psychiatrists and psychologists in managing patient anxieties to improve adherence.

Central disorders of hypersomnolence

What are they?

Hypersomnolence is characterised by recurrent episodes of excessive daytime sleepiness or prolonged night-time sleep that is not restorative. The typical age at onset is between 17 and 24 years, it is present in 1% of the population and is equally common in males and females (Anderson Reference Anderson, Pilsworth and Sharples2007).

Diagnosis and screening

Individuals report a long nocturnal sleep (often more than 9 h a night) and feel unrefreshed on wakening. They frequently have difficulty in waking from sleep and may exhibit profound sleep inertia or ‘sleep drunkenness’, i.e. confusion, motor coordination difficulties and reduced alertness, which may linger for many hours. During the day, they are compelled to nap repeatedly, often at inappropriate times, such as at work or during a social event. The sleepiness is usually experienced as a gradual phenomenon, as opposed to a ‘sleep attack’ (narcolepsy). Daytime napping does not provide relief. Some individuals have a profound loss of functional ability across family, occupational and social settings (Moller Reference Allen, Picchietti and Garcia-Borreguero2008).

The excessive sleepiness is present despite a main sleep period lasting at least 7 h. The symptoms must be present at least three times a week to receive a diagnosis of hypersomnolence disorder, which is further subclassified into acute (symptoms for less than 1 month), subacute (symptoms for between 1 and 3 months) and persistent (symptoms for more than 3 months) (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Other contributing sleep disorders must be excluded, and to this end it is worth undertaking thorough sleep investigations, including actigraphy (for at least 2 weeks), followed by a nocturnal polysomnogram and the Multiple Sleep Latency Test.

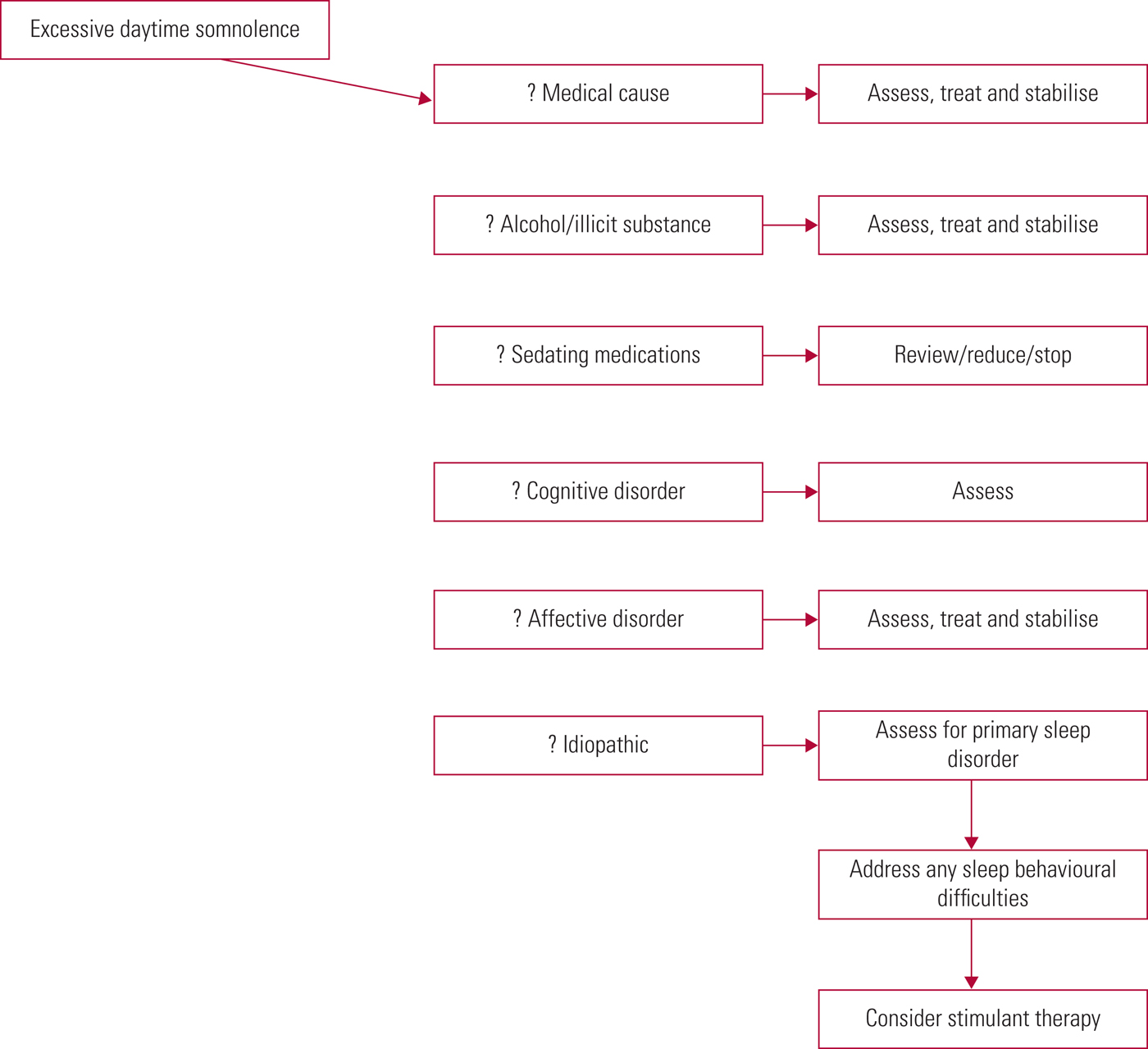

In addition, other medical (e.g. obesity, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, sedating medications), psychiatric (e.g. affective disorders, Alzheimer's disease, sedating medications) and behavioural (e.g. alcohol, illicit substances) causes must be excluded; see Fig. 1 for a suggested approach.

FIG 1 Approach to hypersomnolence.

Caution is advised against automatically ascribing excessive sleepiness only to sedative psychotropics, and it is worth excluding other possible contributors (e.g. a comorbid sleep disorder). More often in clinical practice, the underlying causes of excessive daytime somnolence tend to be multifactorial.

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

Individuals with hypersomnolence disorder may exhibit other psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, irritability, anergia, bradyphrenia, slowed speech, loss of appetite and cognitive difficulties (Bassetti Reference Bassetti and Aldrich1997).

As noted above, hypersomnolence may be associated with affective disorders, substance-related disorders and dementias and can be a side-effect of psychotropic medications.

Treatment

Stimulants (e.g. modafinil, methylphenidate and dexamfetamine) are the mainstay of treatment (Ali Reference Ali, Auger and Slocumb2009). Alerting antidepressants may also be used. Behavioural strategies such as avoiding activities that delay bedtime may provide some relief. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale can be used to monitor response to treatment.

Parasomnias

What are they?

Parasomnias are undesirable physical, experiential or behavioural phenomena that occur at sleep onset and during sleep – things that go bump in the night. They are mainly classified into non-rapid eye movement (non-REM), rapid eye movement (REM) and other parasomnias. Box 1 lists some common parasomnias.

Box 1 Common parasomnias

Non-REM

• Confusional arousals

• Sleepwalking

• Sleep terrors

REM

• REM-sleep behavioural disorder

• Nightmare disorder

• Isolated sleep paralysis

Other

• Sleep enuresis

• Sleep-related groaning

• Sleep disassociation

Diagnosis and screening

Non-REM parasomnias typically occur within the first third of the night. They tend to commence in childhood and diminish with age. There may be up to three episodes per night, and their frequency may vary. Stress, alcohol and sleep deprivation tend to trigger increases in frequency in adults. Typically, a person will have their eyes open during an episode, may leave the bed and will be amnesic for the event the next morning. There is often a positive family history.

REM parasomnias occur in the second half of the night. There may be one or two episodes per night, the person will typically have their eyes closed and they rarely leave the bed.

Diagnosis is usually clinical, but may be challenging, as there is often poor patient recall, no collateral/witness account and routine investigations may be normal.

Table 1 offers guidance on distinguishing between sleep (night) terrors and nightmares. In distinguishing nocturnal panic, there is often a history of daytime anxiety, panic or agoraphobia, and in the night there is physiological warning (e.g. racing heart, shortness of breath, dry mouth), accompanied by an intense feeling of anxiety.

TABLE 1 Main differences between sleep (night) terrors (a non-REM parasomnia) and nightmares (a REM parasomnia)

REM, rapid eye movement.

REM-sleep behavioural disorder (RBD) is more common in men over 50 years of age. In the disorder, REM atonia is lost, so the individual may act out their dreams. The person usually has little, if any, knowledge of their actions, but may recall dream mentation, which often involves fighting others, for example to protect their home or loved ones from intruders.

Video polysomnography may be useful, particularly in excluding any other sleep disorder that may be triggering the parasomnia. For example, OSA may underlie a presentation of RBD (i.e. pseudo-RBD), so in a patient with risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing, home pulse oximetry may be a useful screen. Patients withdrawing from alcohol and benzodiazepines may also present with a pseudo-RBD. Parasomnia behaviour may be difficult to differentiate from nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, and again video polysomnography may be helpful. In patients presenting with adult-onset non-REM parasomnias, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain is useful in excluding structural precipitants.

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

Given their often bizarre motor and/or emotional behaviours, parasomnias may be easily confused with psychiatric disorders. For some, there may be associations with psychiatric disorders and their treatments. In adults with sleep terrors, for example, 30% will have a comorbid psychiatric disorder and 50% will have experienced a stressful life event in the preceding year (Ohayon Reference Ohayon, Guilleminault and Priest1999). Antidepressants can unmask a subclinical RBD or make it worse (bupropion is perhaps the exception) (Postuma Reference Postuma, Gagnon and Tuineaig2013).

RBD is the most robust non-motor predictor of developing Parkinson's disease and it predicts early cognitive impairment and visual hallucinations. Around 50% of patients with RBD have mild cognitive impairment at diagnosis; and by 13 years post-diagnosis, 65% will have developed Parkinson's disease and/or dementia (Fulda Reference Fulda2011).

Treatment

Most non-REM parasomnias are clinically mild and self-limiting. Patient education, reassurance, safety advice and avoidance of triggers will often suffice. Any contributing comorbid sleep disorder should be addressed. Cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I, discussed below) may be useful in stabilising sleep–wake patterns and in teaching relaxation/anxiety-reduction techniques. Patients at risk of injury or harm may require low-dose clonazepam at night (e.g. Markov Reference Markov, Jaffe and Doghramji2006). The Paris Arousal Disorders Severity Scale may be useful in monitoring response to treatment.

In RBD, patient education and safety measures are important. In violent RBD, it is worth advising that bed partners sleep apart (if possible) until the condition is controlled. Any contributing medications (e.g. antidepressants) should be reduced, stopped or switched. Patients with additional excessive daytime somnolence should be investigated further (see ‘Diagnosis and screening’ above). If treatment is necessary, there is randomised control evidence for clonazepam, but it causes daytime sedation in 66% of patients, will worsen OSA and symptoms return on stopping it (Anderson Reference Anderson and Shneerson2009). Melatonin (e.g. modified release tablets 2–8 mg) is a safer option; it works by restoring REM atonia (McGrane Reference McGrane, Leung and St Louis2015). Finally, cholinesterase inhibitors may be useful in patients with Parkinson's disease and RBD (Di Giacopo Reference Di Giacopo, Fasano and Quaranta2012).

In nightmare disorder, offending medications (e.g. beta-blockers, L-dopa) should be reviewed. Imagery rehearsal therapy and CBT may be helpful. Medically, trazodone and prazosin may be considered (Aurora Reference Aurora, Zak and Auerbach2010).

Sleep-related movement disorders: restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep

What are they?

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common neurological disorder, which is clinically diagnosed on history (see below). Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) is a related sleep movement disorder, defined by criteria set out by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014), and requires a nocturnal polysomnogram for diagnosis. Up to 80% of people with RLS exhibit PLMS (Montplaisir Reference Montplaisir, Boucher and Nicolas1998), though the reciprocal relationship is not as robust.

Diagnosis and screening

Patients with sleep movement disorders may present with insomnia, as limb movements prevent sleep onset or disturb sleep maintenance. People with PLMS (and their bed partners) are often unaware of these repetitive leg movements, which disturb sleep maintenance and stage 3 sleep (the most refreshing part of sleep). As a result, they frequently present with excessive daytime somnolence, although to their knowledge they have no apparent difficulties with sleep maintenance.

The essential criteria for a diagnosis of RLS can be summarised as unpleasant sensations in the legs (e.g. pain, tingling, feelings of electricity or whirring), which are associated with the urge to move, which cannot be ignored, and which are partially or wholly relieved by movement (Allen Reference Allen, Picchietti and Garcia-Borreguero2014). The symptoms show diurnal variation, and most commonly come on in the evening when the person is at rest. They may also be episodic in nature. Although the legs are most commonly affected, symptoms may arise from any muscle group, for example restless arms or back. To make the diagnosis, other medical and behavioural factors must be excluded, such as renal failure, diabetes and low ferritin levels.

Although PLMS is diagnosed by polysomnography, it can vary significantly from night to night. Therefore, a negative polysomnogram in the context of a convincing history should be investigated further, for example via domiciliary lower limb actigraphy.

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

Sleep movement disorders and psychiatric disorders are frequently comorbid (Haba-Rubio Reference Haba-Rubio2005). Moreover, many psychotropics can unmask or exacerbate these conditions.

Predictably, all typical antipsychotics with dopamine receptor blocking properties will exacerbate sleep movement disorders. Within the atypical class, case reports of olanzapine and risperidone worsening RLS have been published (e.g. Basu Reference Basu, Kundu and Khurana2014). There are insufficient data available about the effects of other antipsychotics, but as a partial dopamine agonist, theoretically aripiprazole may have a favourable effect on RLS.

Various tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) exacerbate RLS or PLMS; mirtazapine in particular has been strongly implicated (Rottach Reference Rottach, Schaner and Kirch2008). In contrast, bupropion, a dopamine agonist, may help alleviate RLS symptoms.

Centrally acting emetics such as promethazine and over-the-counter antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have also been implicated.

Given the effects of these medications on RLS symptoms, it is important to screen for RLS before starting psychotropic therapy. Up to 66% of patients with moderate to severe RLS will also experience depression and panic disorder (Becker Reference Becker2006). In a patient with severe RLS and mild depressive symptoms, it may be reasonable to treat the RLS first to see whether improvements in sleep and daytime functioning lead to a resolution of depressive symptoms.

In general, anticonvulsants that are associated with pain relief ameliorate RLS symptoms. Gabapentin and carbamazepine are second-line agents in the treatment of RLS, and valproic acid might also be helpful in reducing symptoms.

Treatment

First, all secondary causes must be excluded. In particular, for patients with a ferritin level less than 50 µg/L, iron supplementation should be commenced. If possible, any associated psychotropic should be stopped or switched to one that is not known to exacerbate sleep movement disorders.

Consideration could then be given to a small evening dose of a dopamine agonist (e.g. ropinirole). Compulsive gambling, overeating and hypersexuality have been associated with dopamine agonist treatment of Parkinson's disease and, to a lesser degree, RLS (Moore Reference Moore, Glenmullen and Mattison2014). Therefore, in patients with impulse-control disorder or affective disorders (e.g. bipolar affective disorder) clinicians should be aware of the potential for initiating or exacerbating impulsive behaviour or mood symptoms. Similarly, dopamine agonist treatment may unmask an underlying psychotic illness. Dopamine agonists should never be given to patients with an active psychosis, and caution should be exercised in those with a history of psychosis.

Treatment with alpha-2-delta agonists such as pregabalin may be especially useful, as these will also help protect stage 3 sleep and reduce night-time anxiety, which can be a problem for many patients.

The International RLS Study Group's Restless Legs Syndrome Rating Scale may be useful is monitoring response to treatment.

Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders

What are they?

Our internal biological master clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain. The SCN has direct neural connections with other brain areas and also communicates with the rest of the body by controlling the release of the endocrine hormone melatonin from the pineal gland. The SCN is active in the day and in the presence of light. When the SCN is active it inhibits melatonin secretion. In the evening the SCN becomes less active and the pineal gland starts to secrete melatonin. Melatonin further inhibits the SCN and therefore promotes its own secretion in a positive feedback loop. Melatonin receptors are widely expressed throughout our body and melatonin acts as a signal that ‘tells our body it is night’. In the morning the SCN becomes active again and melatonin levels drop. Circadian rhythm disorders (CRDs) occur when this internal biological clock is disrupted or when it becomes misaligned with the outside world. Table 2 describes the various disorders that fall into this category.

Diagnosis and screening

Generally, patients present with a stable or recurrent pattern of sleep–wake disturbance that leads to sleepiness when the person wants to be awake and alertness when the person wants to sleep. This is often mistaken for insomnia. However, patients with insomnia often report being ‘tired but wired’ when awake, whereas those with a CRD are more likely to be sleepy.

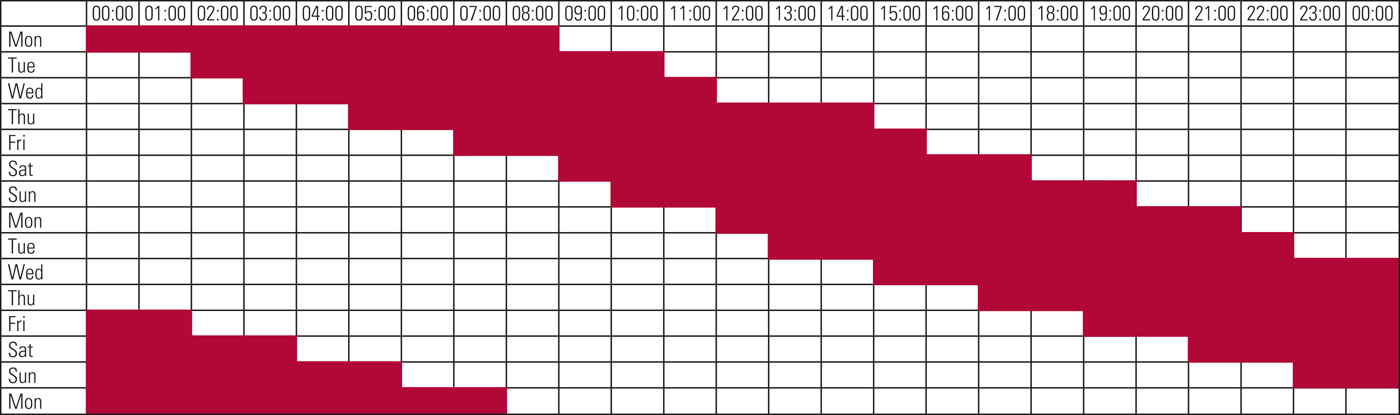

The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of history. Clinicians should ask about typical times of sleep onset and waking when there are no external time constraints and whether these times change when there are external constraints, such as having to rise at a particular time for work. They should determine what time of day the patient feels most alert and most sleepy. A sleep diary for at least 7 days (but ideally longer) that captures work/school and non-work/non-school days is immensely helpful. A visual diary in which the patient colours in the times they are asleep and awake can be more useful than a written diary, as it makes it easier to discern patterns in the sleep (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 An example of a sleep diary in which the patient coloured in the hours she was asleep in red and left the hours she was awake blank. This makes it easy to see the progressive delay in her sleep time, indicating a non-24-hour sleep–wake rhythm disorder.

Actigraphy, which involves wearing an accelerometer on the wrist, can be used to obtain objective, longitudinal data on the patient's sleep cycle (Littner Reference Littner, Kushida and Anderson2003). Actigraphy generates a visual representation of the sleep pattern similar to the diary in Fig. 2 and can be particularly useful if the patient is unable to keep a diary.

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

The circadian rhythm controls not only physiological variables and alertness but also mood. Our mood is lowest around the time of the circadian nadir (when alertness is lowest) in the early hours of the morning (Wirz-Justice Reference Wirz-Justice2008). Most of us sleep through this mood nadir and are therefore rarely exposed to it. However, in delayed sleep–wake phase disorder (DSWPD) the delayed circadian rhythm means that the mood nadir occurs later in the day, when patients are often awake. It is therefore postulated that the high rates of depression in DSWPD (Kripke Reference Kripke, Rex and Ancoli-Israel2008) may be due to the repeated exposure to this mood nadir. Treating the DSWPD may not only treat the sleep disorder but also reduce depressive symptoms (Borodkin Reference Borodkin, Dagan, Winkelman and Plante2010). In patients with non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder there is also a high rate of depression and in some the severity of that depression will vary with the sleep phase, being greater when sleep occurs in the day and lesser when sleep occurs at night (Borodkin Reference Borodkin, Dagan, Winkelman and Plante2010).

It is often assumed that the sleep–wake cycle disruption commonly seen in schizophrenia is due to lack of structure, social isolation or other lifestyle factors. However, circadian rhythm disorders are present in a significant proportion of people with schizophrenia and it may be this underlying biological disorder that leads to the sleep disruption and lifestyle changes (Wulff Reference Wulff, Gatti and Wettstein2010).

DSWPD is also common in children and adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and treatment of the DSWPD can lead to improvements in the ADHD symptoms and daytime functioning (Borodkin Reference Borodkin, Dagan, Winkelman and Plante2010).

Treatment

The treatment of circadian rhythm disorders is complex but relatively free of significant side-effects. The mechanism of the circadian rhythm indicates that there are two ways of intervening in the patient's circadian rhythm. The first is to give the patient melatonin and the second is to use light (preferably sunlight or a seasonal affective disorder lamp). Melatonin will pull the sleep period towards it, i.e. if it is taken before the habitual sleep time the patient will fall asleep earlier; if it is taken after the habitual waking time it will delay their subsequent sleep period. Light has the opposite effect: light before sleep will delay sleep, whereas light on waking will advance the sleep (Morgenthaler Reference Morgenthaler, Lee-Chiong and Alessi2007). In practice the treatment is more subtle than this and the timing of the melatonin or light is absolutely critical, particularly as the specific timings may change from day to day. For example, in our clinic we advise patients with DSWPD to take their melatonin 6 h earlier than the time that they fell asleep the night before. As the therapy takes effect they will start to fall asleep earlier and therefore they will take their melatonin progressively earlier as well.

Insomnia

What is it?

Insomnia is difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep (either because of waking during the night or early morning waking) that leads to dissatisfaction or concern about sleep or to daytime consequences such as mood disturbances, irritability, fatigue, sleepiness, impaired social and occupational functioning, or impairments in memory, concentration or attention (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). The critical point is that there must be some adverse consequence to the sleep pattern. Someone who habitually sleeps for a short period or has fragmented sleep without daytime consequences is likely to be someone who simply needs less than the average amount of sleep (a short sleeper) and would not be considered to have a sleep disorder. It is also important to point out that insomnia is only diagnosed if the sleep complaint is not entirely due to inadequate sleep opportunity (insufficient sleep syndrome) or adverse environmental conditions such as excessive noise and light or an unsafe environment.

For chronic insomnia to be diagnosed the sleep disturbance and daytime symptoms must occur at least three times a week for at least 3 months (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014).

Diagnosis and screening

Insomnia is generally obvious to both patients and clinicians. Where clinicians often err is in either failing to exclude the differential diagnoses or in assuming that the insomnia is a symptom of another condition rather than a disorder in its own right.

Insomnia is a clinical diagnosis and a good history is usually all that is required to make the diagnosis. Objective sleep studies are rarely needed in insomnia assessments unless the clinician suspects that there are other sleep disorders present, such as PLMS or OSA. A sleep diary for at least 7 days can be very helpful, particularly as patients often tend to describe the worst-case scenario rather than their typical symptoms when asked to describe their sleep. The clinician should enquire about work patterns, environmental factors, daytime naps, caffeine and alcohol consumption, medication use and what activities aside from sleep occur in the bedroom.

Differential diagnoses that must be discounted include CRDs, RLS and PLMS, OSA and insufficient sleep (behaviourally induced). If these diagnoses are missed, then treating the disorder as an insomnia is likely to lead to suboptimal results or may even make the disorder worse. For example, antihistamines or sedative antidepressants are often prescribed for insomnia, but they can exacerbate RLS. For the same reason, if the patient does not respond to standard insomnia treatments the clinician should consider the possibility that they might have a different sleep disorder that was missed at the initial assessment.

A common mistake is to assume that the insomnia is simply a symptom of depression and that treating the depression will resolve the insomnia as well. As a result, many insomnia patients are treated with antidepressants such as SSRIs, which may actually make the insomnia worse. It is also enormously irritating for euthymic patients with insomnia to be told that they are depressed; they feel very misunderstood and frustrated that their primary complaint is not being directly addressed. Where insomnia and depression coexist, the insomnia should not be thought of as being secondary to the depression: rather, they should be seen as comorbid conditions. This approach is reflected in DSM-5, which has deliberately omitted the terms ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ from the insomnia diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Relationship to psychiatric disorders

Of all the sleep disorders, insomnia is the one that can most clearly lay claim to being a psychiatric disorder in its own right. It is often driven by psychological factors and can have a similar impact on quality of life as major depressive disorder (Katz Reference Katz and McHorney2002). There is also a high rate of insomnia in psychiatric patients: for example, one study found that 60% of new referrals to a psychiatric clinic complained of insomnia (Okuji Reference Okuji, Matsuura and Kawasaki2002) and another reported that 40% of patients with insomnia had a comorbid psychiatric disorder (Roth Reference Roth2007). All psychiatric patients should therefore be screened for insomnia.

There is mounting evidence that insomnia is a risk factor for the subsequent development of other psychiatric disorders, particularly depression. Where insomnia and depression coexist, the insomnia occurs first in 69% of patients (Johnson Reference Johnson, Roth and Breslau2006) and insomnia may predict subsequent depression decades after the insomnia develops (Chang Reference Chang, Ford and Mead1997), making it unlikely that it is just a prodromal symptom of depression. Patients with insomnia have a two-fold risk of developing depression (Baglioni Reference Baglioni, Battagliese and Feige2011) and so they should be monitored closely. However, if the insomnia resolves, the risk of subsequent depression is reduced (Franzen Reference Franzen and Buysse2008). Similarly, the presence of insomnia predicts a poorer response to psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression, and if insomnia remains as a residual symptom when depression remits it predicts a higher rate of relapse. And although there is some debate about whether insomnia is an independent risk factor for suicide, it is undoubtedly a marker for increased suicide risk (Franzen Reference Franzen and Buysse2008). Fortunately, there is also evidence that treating the insomnia can lead to improved outcomes in the comorbid psychiatric condition (Manber Reference Manber and Chambers2009) and we discuss this in the next section.

Finally, it is important to remember that many psychiatric drugs have insomnia as a side-effect and clinicians should be cognisant of this when prescribing. As a rule of thumb any drug that increases serotonergic, noradrenergic, dopaminergic or cholinergic tone has the potential to promote wakefulness and cause insomnia. However, in some drugs with antihistaminergic, anti-adrenergic or anticholinergic properties the sedative effects may counterbalance or outweigh the stimulant effects.

Treatment

There are two approaches to the treatment of insomnia: medication and cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). The majority of hypnotics licensed for use in insomnia (benzodiazepines, zopiclone and zolpidem) act by enhancing the inhibitory effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) via the benzodiazepine receptor. A slow-release version of melatonin and some antihistamines are also licensed for insomnia treatment. These medications can be safe and effective if used in the right way, at the right dose and with the right patient, but studies of long-term efficacy (more than a year) are lacking.

Probably the most important factor to consider when prescribing is the half-life of the drug. Most hypnotics have a quick onset of action but there are large differences in their half-lives and duration of action. Shorter-acting drugs (e.g. melatonin and zolpidem) are good for sleep-onset insomnia, but may be less effective in sleep-maintenance insomnia. Longer-acting drugs (e.g. zopiclone and temazepam) are likely to be good for sleep onset and maintenance, but carry the risk of morning hangover and should be used with caution in people who drive.

In patients with insomnia and comorbid psychiatric conditions there is good evidence that hypnotics are effective at treating the insomnia. Hypnotics may also accelerate or improve the response to standard treatments for generalised anxiety disorder, depression or schizophrenia (Pollack Reference Pollack, Kinrys and Krystal2008; Fava Reference Fava, Schaefer and Huang2011; Tek Reference Tek, Palmese and Krystal2014).

Hypnotics are only licensed for short-term use in the UK. The problem with this is that the drugs only work for as long as they are being taken (Riemann Reference Riemann and Perlis2009) and insomnia is often a chronic condition. We therefore find ourselves in a situation where there are only short-term licensed medications for a long-term problem. Fortunately, there is an alternative approach to the long-term treatment of insomnia in the form of CBT-I.

CBT-I is an effective, evidence-based treatment for insomnia that can be delivered one-to-one, in groups or online. Indeed, in chronic insomnia CBT-I should be the first-line treatment. It has also been shown to be an effective intervention in patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions (Taylor Reference Taylor and Pruiksma2014) and there is mounting evidence that CBT-I can have a treatment effect on those comorbid psychiatric disorders. For example, a study comparing online CBT for depression with online CBT for insomnia in people with comorbid depression and insomnia found that the CBT for insomnia was more effective than the CBT for depression at improving sleep and that the two interventions were equally effective at treating the depression (Blom Reference Blom, Jernelöv and Kraepelien2015). Similarly, CBT-I has been shown to reduce sleep complaints and persecutory delusions in people with psychosis (Myers Reference Myers, Startup and Freeman2011).

Conclusions

There is a wide variety of sleep disorders and they all have the potential to affect mental health. Sleep can also be disrupted by psychiatric disorders and the treatments for those disorders. It may seem counter-intuitive that what happens in a person's airways or legs could have an impact on their mental health, but sleep medicine demonstrates how closely integrated our physiological and psychological systems can be. This is a rapidly growing area and we anticipate that sleep medicine will play an increasing role in managing psychiatric conditions in the future.

Sleep is important to patients and having a psychiatrist take a genuine interest in their sleep makes them feel understood and cared for. By the time patients have their sleep disorder properly investigated and treated they will often have endured many years of suffering and frustration. Psychiatrists may be the first, or perhaps the only, professionals to ask a patient about their sleep and so it essential that they are able to recognise sleep disorders. By identifying and treating their patients’ sleep disorders, psychiatrists have the opportunity to dramatically improve their patients' quality of life, their physical well-being and their mental health.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 In comorbid depression and insomnia:

a treating the insomnia is not necessary if the depression is adequately treated

b treating the insomnia will not have any impact on the depression

c CBT-I may lead to improvements in depressive symptoms

d the insomnia should be seen as a symptom of the depression

e SSRIs do not exacerbate insomnia.

2 In circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders:

a the disordered sleep pattern is the result of lifestyle choices

b melatonin and light treatment can be effective interventions

c going to bed at the same time every night is the most important intervention

d delayed sleep–wake phase disorder is more common in the elderly

e these disorders are rarely misdiagnosed as insomnia.

3 Of the following psychotropics, the one not known to precipitate or worsen sleep movement disorders is:

a mirtazapine

b olanzapine

c clozapine

d bupropion

e risperidone.

4 Of the following conditions, the one not classified as a non-REM parasomnia is:

a confusional arousal

b sleepwalking

c sleep eating

d sleep terrors

e nightmare disorder.

5 Symptoms characteristic of hypersomnolence disorder include:

a hypnogogic hallucinations

b sleep inertia/drunkenness

c sleep paralysis

d hypnopompic hallucinations

e cataplexy.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 b 3 d 4 e 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.