LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the different stages of the mourning process

• recognise the important role of mourning in different mental illnesses

• psychologically formulate psychiatric presentations.

‘What it is to be human. It seems to me that the common agent that binds us all together is loss, and so the point in life must be measured in relation to that loss. Our individual losses can be small or large. They can be accumulations of losses barely registered on a singular level, or full-scale cataclysms. Loss is absorbed into our bodies from the moment we are cast from the womb until we end our days, subsumed by it to become the essence of loss itself.’

(Cave, Reference Cave2022)This article brings together the psychiatric and psychoanalytic views of mental illness to provide a model by which to understand the nature of psychiatrically diagnosed disorders. Why has this person developed this particular disorder, been diagnosed and classified in this particular way, at this point in their life? The psychiatric diagnostic system can be understood and enriched through the psychodynamic lens. Psychiatrists tend to view the mind from the outside and diagnose different disorders depending on the symptom constellations observed, using classification systems (e.g. ICD and DSM). Psychoanalysts look from the inside of the mind at the unifying human psychodynamics where mental illness is understood to arise from difficulties in the response to the human experience of loss and grief (as described by Nick Cave above).

In summary, this article will argue that psychiatric illness can be understood to result from ‘pathological mourning’ due to arrests, or retreats, in the passage through the mourning process. The characteristic symptoms of different psychiatric illnesses used to classify disorders can be conceptualised as resulting from the overuse of different constellations of psychic defences (Table 1) used at specific and different stages in the mourning process. Differently classified illnesses have different symptoms depending on the particular point in mourning where the arrest occurs. Key terms used in the article are defined in Box 1.

TABLE 1 Psychic defences

BOX 1 Definitions of terms

Mourning: The psychological processes that are set in motion by a loss.

Grief: The sequence of subjective states that follow loss and accompany mourning.

Ego: One of three parts of Freuds ‘structural model’ of the psyche that mediates between the ‘id’ and the ‘superego’. The ego engages with reality and it is where self-identity is located. The id is entirely unconscious and holds the basic instinctual urges, such as aggression and sexuality. The superego functions as a conscience, repressing what it considers to be morally unacceptable.

Imago: The unconscious mental image of another person. This image becomes more accurate through effective mourning.

Object: In object relations theory, early infantile experience is describe as relationally based. The attachment energy, or libido, is focused on people and things, which are defined as ‘objects’. There is an internalisation of representations of these ‘objects’ that populate the mind and increase in complexity and depth through mourning and separation.

Lost object: What has been lost. The focus of the grief. The loss of the object triggers the mourning process. This can be symbolic as well as concrete. For example it can be an actual person/relationship, a view of oneself (considered a narcissistic loss) or a loss that changes one's perception of the world.

Good object and bad object: Early primitive objects internalised that both represent aspects of the same primary care giver. The ‘good object’ is experienced by the infant when their needs are being met and they experience satisfaction, and the ‘bad object’ is experienced when they are not and they experience frustration. Through mourning it is recognise that both represent aspects of the same external other.

Mentalise: The ability to reflect on, and to understand one's own state of mind. To have insight into what one is feeling and why. To be able to conceptualise other people's mental states and to recognise that they may be different to one's own.

Symbolic capacity: A symbol is an indirect form of representation that allows an individual to think about people, objects and events that are not concretely available. These symbols are available for utilisation intrapsychically to represent ideas, conflicts or wishes. To generate these representations in psychic space is an abstract task and requires cognitive capacity. It moves the concrete to the abstract. Symbolic capacity is needed to be able to think and play with ideas in the mind:

‘The symbol proper, available for sublimation and furthering the development of the ego, is felt to represent the object; its own characteristics are recognized, respected, and used. It arises when depressive feelings predominate over the paranoid-schizoid ones, when separation from the object, ambivalence, guilt, and loss can be experienced and tolerated. The symbol is used not to deny but to overcome loss’ (Segal Reference Segal1957).

Symbolic processing: The process of thinking using symbols where certain ideas, pictures or other mental statement acts as intermediaries of thought (Segal Reference Segal1957).

Omnipotence: A defensive position where one has unlimited/great power and vulnerability is avoided.

Sadomasochistic engagement: This describes a method of relating and managing intimacy that keeps the object at a controlled distance. There is usually a movement from a sadistic state of mind where there is a feeling of power and control to a masochistic state of mind where there is a feeling of vulnerability and exposure. This is experienced as exciting. A degree of this relating is commonplace, but it can become disturbed or entrapping under certain circumstances (Glasser Reference Glasser and Rosen1979).

Phantasy: The ‘ph’ spelling is often used to differentiate this unconscious process from fantasy, which is conscious and deliberate.

Libido/psychic energy: The life force driving and sustaining mental activity. In much psychoanalytic theory the ‘id’ is considered to be the source of this energy. It can be considered as mediating desire, curiosity and passion.

Transitional space: The conceptual space that develops between the infant and caregiver through separation and individuation. This space allows for a move away from concrete thought and functioning to symbolisation, complex thought, mental creativity and play:

‘I have introduced the terms “transitional object” and “transitional phenomena” for designation of the intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear, between the oral erotism and true object-relationship, between primary creative activity and projection of what has already been introjected, between primary unawareness of indebtedness and the acknowledgement of indebtedness’ (Winnicott Reference Winnicott1953)

The obstruction, in pathological mourning, can result from combinations of different aetiological factors (A), which include:

• genetics (A1)

• organic brain injury/disease (A2)

• lack of developmental containment (A3)

• a loss of such magnitude that a retreat from reality is essential for psychic and/or physical survival (A4)

• collusion of the social system around the bereaved to perpetuate the disturbance (A5).

The normal mourning process

‘[The normal mourning process] carried out bit by bit, at great expense of time and cathectic energy [ … ] Each single one of the memories and expectations in which the libido is bound to the object is brought up and hyper-cathected, and detachment of the libido is accomplished in respect of it.’

(Freud, Reference Freud1917)Psychoanalysts have explored in detail the normal mourning process, describing it as excruciatingly painful and laborious ‘work’ which, when successful, is rewarded by ego growth through the installation of reality-based imagoes of lost ‘objects’ (representations of lost meaningful attachment figures) in the internal world. This results in an enrichment of psychic life and a deepened capacity for joy and love. This process is life's great challenge and is fundamental to individuation and separation (Freud Reference Freud1917; Fairbairn Reference Fairbairn1941; Balint Reference Balint1952; Fromm Reference Fromm1956; Bowlby Reference Bowlby1988; Kernberg Reference Kernberg2011):

‘Implicit in mature love is an honest acceptance of one's essential need of the other in order to achieve full enjoyment and security in life’ (Kernberg Reference Kernberg2011).

Many psychoanalysts believe that the template for lifelong mourning is developed in the early years of life (Balint Reference Balint1952; Fairbairn Reference Fairbairn1943; Fromm Reference Fromm1956; Klein Reference Klein1957; Kernberg Reference Kernberg2011). It is during this time that the infant faces their first great losses as they start the process of separation and individuation (Klein Reference Klein1957). The mourning process occurs for the first time in the first year but thereafter a multitude of times, after every loss that occurs throughout a lifetime at varying degrees of intensity on a daily, weekly, monthly and yearly basis (Klein Reference Klein1957). Every time a loss occurs the process is repeated and reworked and the internal world and the psychic capacities of the individual grow and deepen. With this development there is an increase in the capacity to form truly loving intimate relations. These analysts believed that how this process is negotiated in early life determines the individual's future capacity to deal with losses, and therefore their later predisposition to psychiatric illness.

Stages of mourning

‘The nature of sorrow is so complex, its effects in different characters so various, that it is rare, if not impossible, for any writer to show an insight into all of them.’

(Shand Reference Shand1914: p. 361)Different physicians, including Parkes (Reference Parkes1988) and Kubler-Ross (Reference Kubler-Ross1969), and psychoanalysts, such as Freud (Reference Freud1917), Fairbairn (Reference Fairbairn1941), Klein (Reference Klein1957), Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1988) and Steiner (Reference Steiner1990), have observed different stages of the mourning process. Although making it clear that individuals negotiate loss in unique ways, overall they have described a process of breakdown and reconstruction, disorganisation and reorganisation. Colin Murray Parkes calls it a ‘psychosocial transition’ where the ‘assumptive world’ (all that we assumed was securely in place) is thrown into disarray and has to be rebuilt (Mallon Reference Mallon2008).

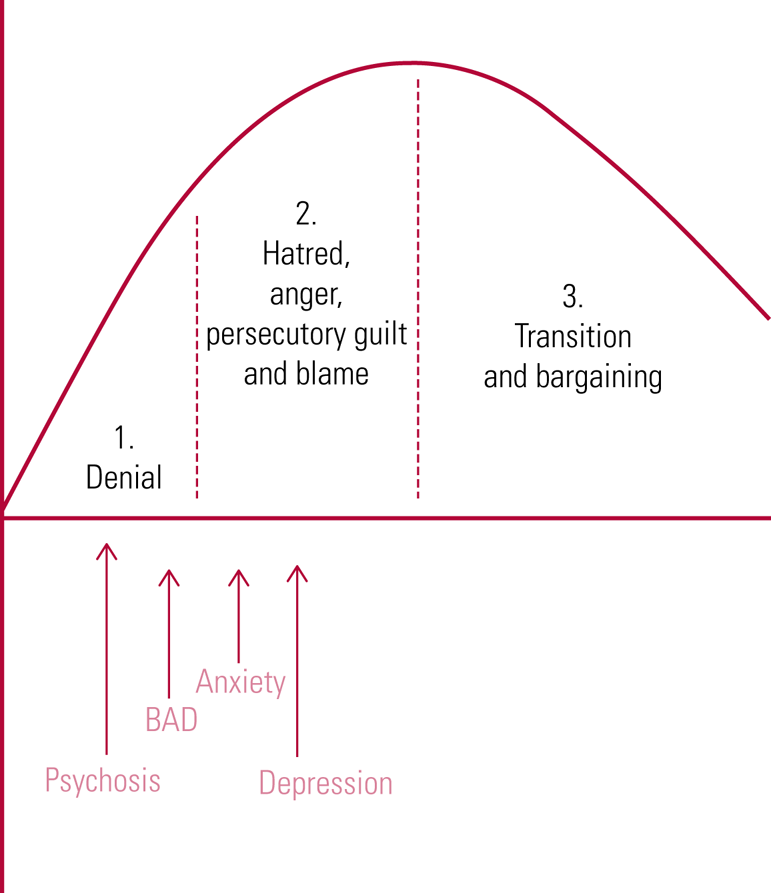

The mourning process can broadly be divided into five stages that clinicians have described in different ways (Fig 1). To assist further discussion, they will be identified here as:

(1) denial;

(2) hatred, anger, persecutory guilt, and blame;

(3) transition and bargaining;

(4) sadness and neurotic guilt;

(5) acceptance.

FIG 1 The stages of mourning.

Stage 1: Denial

‘[M]an's usual response is “No, it cannot be me.” Since in our unconscious mind we are all immortal, it is almost inconceivable for us to acknowledge that we too have to face death.’

(Kubler-Ross, Reference Kubler-Ross1969: p. 55)Stage 1 starts in the period directly after the loss. The ego is overwhelmed with anxiety and the capacity to mentalise and therefore symbolise is lost (Bateman Reference Bateman and Fonagy2013). Primitive psychotic defences, including denial, splitting and projection, that can be mobilised rapidly and require little psychic capacity, are utilised to buffer and titrate the awareness of reality. This results in a dissociation from the experience of loss and the initial characteristic picture of numbness and unreality. The loss itself and the hatred of reality generated by it are totally denied.

Stage 2: Hatred, anger, persecutory guilt and blame

Hate [ … ] in a healthy man is only potential or incidental [ … ] it should be more like acute anger; in contrast to love, hate should easily and speedily dissipate.’

(Balint Reference Balint1952: p. 358)Once the immediate shock is buffered and some symbolic capacity recovered, there is some re-establishment of engagement with reality. The primitive immature defences start to lessen their hold on the psyche and those that utilise some symbolic functioning, and are therefore less radical, are activated. The emotional temperature changes from numbness and disconnection to hatred, anger and protest (Balint Reference Balint1952; Kubler-Ross Reference Kubler-Ross1969; Parkes Reference Parkes1988). In the early part of stage 2, murderous phantasies and impulses unconsciously directed towards the lost object are common:

‘Since none of us likes to admit anger at a deceased person, these emotions are often disguised or repressed and prolong the period of grief or show up in other ways’ (Kubler-Ross Reference Kubler-Ross1969: p. 18).

The hatred and later, the more nuanced anger, are not initially directed at who or what is lost, which is initially preserved through the use of defences characteristic of stage 2. These include: projection, displacement, anger turned inward and identification. As a result, a perceived less valuable external ‘bad object’ is labelled as the source of the problem. As time progresses, and as long as the ‘bad object’ survives the attacks, the rage at the real subject of the loss can be acknowledged and mourning can progress:

‘If you had stood in front of me when I was so full of hatred after my daughter's death, I could have killed you and not thought twice about it’ (Grieving mother).

This is a highly emotionally charged and challenging stage. The reality of the loss and the powerlessness of the individual are still resisted. The psychic pull of omnipotence and sadomasochistic engagement with the ‘bad object’ is exciting and hard to relinquish (Steiner Reference Steiner1990). It is during stage 2 that the ability to grieve and the nature of the relationship to the lost object are of utmost importance. As described above, if there has been successful mourning in childhood true loving feelings generally prevail (Abraham Reference Abraham1911; Balint Reference Balint1952; Steiner Reference Steiner1990), because the individual has developed confidence they can survive the pain of loss: through effective mourning they have internalised ‘good objects’ that they can utilise to support them in their grief. The ‘bad object’ is not successfully destroyed and the difference between it and the real external object can start to be seen (Bion Reference Bion1962).

Psychiatrists and psychiatric services can play an important role as the ‘bad object’ through stage 2: it is important that those involved do not identify too strongly with this projection for the well-being of those grieving and to prevent a collusion that arrests mourning (A5).

Stage 2 is potentially a very dangerous stage of mourning. Arguably, many of the destructive acts of humanity, including wars, murder and violence, have resulted from a lack of containment and arrests during stage 2 of the mourning process. The war on Afghanistan, starting just 15 days after the September 11 attacks in the USA, is likely to have been sanctioned, in part, by the fear, anger and unconscious desire for retribution resulting from the grief following this profound loss event (Witte Reference Witte2010).

Stage 3: Transition and bargaining

‘I do not normally pray but I have been since my diagnosis – I think “If I pray to you now Lord, I will do anything you ask [ … ] will you tell the cancer to go away?”.’

Patient‘You were giving him, my father, another chance, even with your nose still crooked from his countless backhands.’

(Ocean Vuong, Reference Vuong2014: p. 28)During the transitional stage there is a gradual growing awareness of the reality of the loss, although it continues to have an unreal quality and there is some hope, through the defence of ‘magical thinking’, of reversal (Fairbairn Reference Fairbairn1941; Steiner Reference Steiner1990). It is a time of ‘hope and hopelessness’. With the recovering of symbolic functioning there is the development of a ‘transitional’ space (Winnicott Reference Winnicott1971), where the loss can be played with in phantasy. This transitional phase continues until there is finally a taking in, or submission to, the full reality of loss.

Stage 4: Sadness and neurotic guilt

‘His numbness or stoicism, his anger and rage will soon be replaced with a sense of great loss.’

(Kubler-Ross, Reference Kubler-Ross1969: p. 97)During this stage the loss is actively mourned, and painful sadness predominates. This grief takes a considerable amount of psychic energy, libido (Freud Reference Freud1917), which is directed into the internal world and therefore cannot be externally discerned. Instead, the individual suffering tends to appear listless, withdrawn and lacking in motivation. Gradually, through the ‘work’ of stage 4, a genuine compassionate resilient mental representation of the ‘lost object’ is internalised. This is the time of realistic neurotic guilt, and gradual reparative feelings and behaviours.

Stage 5: Acceptance

‘I hold it true, whate'er befall; / I feel it when I sorrow most; / ’Tis better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all.’

(Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), In Memoriam A. H. H.)In this final stage the pain eases and there is the possibility of learning to live with the loss. Gradually the memories bring pain, joy and gratitude for having loved and for life itself. These stages are negotiated repeatedly, often with some degree of cyclicity.

Pathological mourning and psychiatric illness

‘[ … ] disease proceeded from an attitude of hate [ … ] paralysing the patient's capacity to love.’

(Abraham, Reference Abraham1911: p. 19)Freud (Reference Freud1917), Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1988), Abraham (Reference Abraham1911) and Steiner (Reference Steiner1990) all describe psychiatric illness resulting from defensive processes ‘interfering with’ or ‘fixating’ the progress of mourning in stages 1 and 2 (Fig 2). The illness provides a ‘refuge’, a defence against reality. This is described by Steiner as a ‘psychic retreat’. Although some time spent in this refuge can be healthy, providing some protection and defence against reality, when entrenched the retreat leads to developmental arrest and psychiatric illness. The longer reality is avoided, the greater the losses to be mourned. As well as the original loss there is now the loss of the time spent in withdrawal:

‘The patient who has hidden himself in the retreat often dreads emerging from it because it exposes him to anxieties and suffering – which is often precisely what had led him to deploy the defences in the first place’ (Steiner Reference Steiner1990).

FIG 2 The place of arrest in the mourning process for various diagnosable illnesses. BAD, bipolar affective disorder.

For some, remaining in the retreat may be a matter of psychic and physical survival. It is frequently reported that a patient has the greatest risk of death by suicide when starting to recover from a psychiatric illness (Chung et al Reference Chung, Ryan and Hadzi-Pavlovic2017; Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership 2022).

This article puts emphasis on the view held by Freud (Reference Freud1917), Abraham (Reference Abraham1911), Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1988) and Steiner (Reference Steiner1990) that the symptoms that define every DSM/ICD diagnosis of mental illness are determined by the point in the mourning process where the arrest occurs. This in turn is determined by the individual's vulnerabilities and the constellations of defences they constitutionally call on. If only psychotic defences can be used, as in dementia and some forms of schizophrenia, the arrest will occur very early in the mourning process, in denial, and a psychotic illness will be the result. If, during childhood, anger was not an acceptable emotion and was not contained, it is likely that the arrest will be in stage 2 of the mourning process, where anger is mobilised, and the presentation of illness will be that of depression:

‘When I was a child, our parents would become absolutely furious if my brother or sister or I cried. [If] one of us did cry they both became almost insane in their anger toward us’ (Strout Reference Strout2022: p. 48).

Some symptoms similar to those of mental illness, such as hallucinations, guilt, anger, withdrawal and behavioural disturbance, are normal in mourning. It is when these become stuck and intractable that a classifiable disorder develops.

Examples of psychiatric illness

Primary psychotic illness

The symptoms used to diagnose psychotic illness according to ICD and DSM broadly include:

• delusions

• hallucinations

• perceptual disturbances

• severe disruption of ordinary behaviour

• abnormality of thought experience that can be identified in speech structure

• cognitive effects, including negative symptoms, where the level of functioning is below the level achieved prior to the onset.

These symptoms may be understood to result from the overuse of primitive, immature, psychotic defences such as denial, projection, splitting and rationalisation. These defences do not require higher-level cognitive and symbolic functioning (Lucus Reference Lucus2009; Gabbard Reference Gabbard2014). Around 30–40% of illnesses that present to mental health services with psychotic symptoms recover and full symbolic functioning is regained (Li Reference Li, Rami and Lee2022). It is worth noting that a transient psychotic state can occur when the brain is strained or tired and with some drugs, such as cannabis and alcohol. If an individual is deprived of sleep over a significant period, they are prone to develop fleeting psychotic experience. However, in some the psychotic state is persistent and the illness is progressive. Recent developments in research in schizophrenia shows that in a number of patients there is a reduction in cerebral grey matter before any positive symptoms of the illness become apparent (Nenadic Reference Nenadic, Yotter and Sauer2015). This cognitive impact explains the intractable course for some: the illness in itself is a huge loss of identity, future and capacities, and then in turn it robs the individual of the means of working through this loss.

Case vignette 1: Schizophrenia (ICD-11 6A20, DSM-5 F20.9)Footnote a

Mr R was a university student who had achieved well in all his exams. He had family history of mental illness. One maternal uncle had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and the other a bipolar disorder. His first year at university seemed to be going as expected; however, soon his parents found it difficult to contact him. When he came home at the first Christmas break, he did not seem himself. He was withdrawn and stayed in his room smoking cannabis and playing computer games. Soon after his return to university his parents began hearing concerning reports. He had started to behave oddly. He had lost a lot of weight and was not caring for himself. He told his housemates that he believed that a secret organisation was following him and had been tracing his work on the internet because, he said, they found out that he understood the networks of all governments.

Mr R was admitted to hospital voluntarily. He willingly agreed to a brain scan so he could show his family that a chip had been implanted in his brain by this secret organisation. This scan showed enlarged brain ventricles and a loss of brain volume. He was subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia. He left hospital 6 months later. He was stable on antipsychotic medication, but he did not recover his symbolic capacities and cognitively he was severely disabled. He moved from the ward to accommodation with 24 h support.

In this case Mr R had a significant genetic component to his illness (A1). Neurodegeneration had robbed him of significant symbolic functioning (A2). His mental capacities decreased, and the only defences available to him were primarily primitive in nature. At no time did Mr R express anger or sadness. He remained in denial about his illness.

Case vignette 2: Delusional disorder (ICD-11 6A24, DSM-5 F22)

Miss L was a 60-year-old woman presenting for the first time to psychiatric services. She had developed a psychotic illness following her mother's death. She came from a wealthy background and had never left home, continuing to live with her mother and never finding a partner, studying or working. She believed that her mother had not died but was being experimented on at the local hospital. She lived the rest of her life with a high level of support from psychiatric services and maintained this delusion.

In this example Miss L had difficulties in developmental containment and had never managed to develop a mature capacity for mourning. Separation from her mother had not been possible (A3). The death of her mother was therefore too large a loss for her to cope with (A4). She remained stuck in stage 1 of mourning, with a persistent delusion.

Case vignette 3: Psychotic disorder unspecified (ICD-11 6A25, DSM-5 F298.9)

Mr P was detained in prison. He was a man in his 30s who had no history of psychiatric illness and no previous criminal record. He had been working successfully in retail before his arrest. He was charged with the murder of his pregnant girlfriend. He made no attempt to cover up the crime. When seen by the prison psychiatric team, his behaviour was bizarre. He was clearly perplexed and disordered in thought and speech. He believed his girlfriend was still alive and he denied all knowledge of the crime. He was diagnosed with a psychotic illness. He remained unwell and was transferred to a forensic hospital, where he remained for the next 10 years.

In this case Mr P developed a psychotic illness because the loss itself and the role he had played in it was too great for him to acknowledge (A4). He had to remain in a state of total denial to retain his unawareness. This therefore was an arrest in stage 1 of mourning and the symptoms were of psychosis.

Bipolar affective disorder (ICD-11 6A60, DSM-5 F31).

According to ICD and DSM, bipolar affective disorder is characterised by two or more episodes in which mood and activity levels are significantly disturbed, this disturbance consisting on some occasions of an elevation of mood and increased energy and activity (hypomania or mania) and on others of a lowering of mood and decreased energy and activity (depression).

The classic symptoms of mania when it predominates are:

• elevated mood

• increased energy

• increased mental and physical activity, including pressure of speech and distractibility

• decreased sleep

• loss of social inhibitions, such as increased spending and sexual disinhibition

• inflated self-esteem and grandiosity, which can become delusional.

Bipolar affective disorder has strong biological and developmental factors (A1, A3) and can be challenging to diagnose because in practice, the symptoms vary. In many cases there are significant psychotic symptoms which are exacerbated by the lack of sleep and overactivity inherent in the illness. Cognitive dysfunction also increases as the illness progresses (A2).

In this disorder ‘manic defences’ predominate. These are a ubiquitous group of mental manoeuvres used in stage 1 of mourning to deny the psychic reality of loss. The defences of denigration, denial, projection and omnipotence are used to control, maintain contempt for and triumph over the lost object. Self-aggrandisement, omnipotent self-sufficiency and wish fulfilment are used to maintain this superior position. If what has been lost has little meaning or value, then there is little to grieve for (Klein Reference Klein1935; Rivierre Reference Rivierre1936). When manic defences are excessively strong, vicious circles are set in motion. The individual feels unconsciously guilty for their attacks, the anxieties underlying the disorder increase and fixation occurs. Symptoms of mania and psychosis develop, and grandiose delusions are common.

Case vignette 4: bipolar affective disorder, current episode manic (ICD-11 6A60.1, DSM F31.2)

Mr M was a 31-year-old high-functioning lawyer who was admitted to a psychiatric ward with florid manic symptoms. He had a family history of significant mental illness. He had a difficult early life. His parents divorced when he was 9 and his father had no subsequent contact with the children or their mother. Mr M said that this had little effect on him and that it was only his mother who was important. His father died around 18 months before his admission. It was after this loss that he gradually became ill with symptoms of a manic episode.

In this case Mr M had genetic vulnerability (A1) and a lack of containment in early childhood with the loss of his father from the family (A2). This loss was not acknowledged and mourned. Later, the death of his father was the primary factor in Mr M's illness. There was a build-up of denied grief and Mr M arrested in stage 1 of mourning, developing symptoms of a manic episode. He subsequently recovered with mood-stabilising medication and psychotherapy. He suffered a subsequent episode 10 years later when he stopped taking his medication.

Anxiety disorder (ICD-11 6B, DSM F40–F41)

According to ICD and DSM the manifestation of anxiety is the primary symptom in these disorders. The arrest in mourning is between stages 1 and 2 and there is still a denial of the source of the loss. The defences utilised are primarily immature, although some more neurotic defences from stage 2, such as regression, isolation of affect and reaction formation, are also employed.

Case study 4: hypochondriasis (ICD-11 6B23, DSM F45.21)

Dr J was born in the UK just after both his parents fled from Germany in 1933. When he was 3 years old his mother became terminally ill. Throughout the years of her illness, the young boy was told that he could not see her because she was ‘poorly’. After her death, Dr J became an anxious child and during much of the rest of his childhood was preoccupied with anxieties about his health. He would repeatedly ask his father ‘Am I poorly, will I die like my mother?’ This drove his father to distraction because no matter what he said and how much he reassured his son, the boy repeatedly asked him the same question. His father lost his temper and told Dr J when he was 10 that if he continued like this he would be sent to boarding school.

Throughout his adult life, Dr J worked as a doctor and hid his hypochondriasis. He often quietly thought that he was dying of various diseases. When Dr J's father died, he said he felt ‘nothing’. With retirement, his anxiety became worse and he had various agitated depressive breakdowns which became delusional at times, when he thought he was dead or dying.

In this case, there was an early lack of containment for Dr J following the loss of his mother (A3). In adulthood, Dr J found a way to manage his illness by working hard and projecting the ill part of himself into his patients. He had two losses in later life, with the loss of his father and his retirement, and he developed a more overt mental illness. He denied the feelings about the loss of his father and projected more profoundly into his body the anxieties about death that his patients had previously held for him. With age he also had some cognitive decline and developed additional psychotic symptoms (A2).

Depressive disorder (ICD-11 6A7, DSM-5 F32)

In depression the arrest is in stage 2 of mourning, when a greater symbolic capacity is achievable and neurotic defences are mobilised. There is some degree of acknowledgement of loss. The anger and hatred meant for the lost object generated in this stage of mourning are turned on the self through the defence of anger turned inwards. This results in the recognised symptoms used for diagnosis, including low mood, anhedonia, guilt and worthlessness.

Case vignette 5: Major depressive disorder, current episode moderate (ICD-11 6A70.1, DSM-V F32.1)

Mr H was sent to boarding school when he was 7. He was initially very distressed but learned to survive by joining in with the sadomasochistic games and bullying of his classmates. He achieved well academically and worked in the financial markets. He married a woman whom he met at university, and they had children. When the children left home, his wife told him that she wanted a divorce. This brought about a depressive breakdown for Mr H. He attacked himself, blaming himself for the marital breakdown and disappointing his wife. He expressed suicidality and hopelessness. His wife felt she could not leave because he might harm himself.

In this case Mr H had a lack of developmental containment as a result of premature separation (A3). He lacked the capacity to mourn the breakdown in his marriage and he retreated from reality (A4). The anger directed at his wife, which resonated with the anger he had felt earlier towards his mother for being sent to boarding school, was turned against himself. His suicidality served to control his wife, stopping her from leaving, and maintained his illness (A5).

Conclusions

An understanding of the importance of the role of mourning in psychiatric illness allows for clarity of formulation and renders diagnosis understandable at a deeper level. The symptoms of illness can be understood as resulting from the overuse of different constellations of psychic defences activated in different stages of the mourning process. Looking for the loss event that underpins the disorder helps determine therapeutic treatment options. It increases the chance of authentic therapeutic engagement and recovery. This article is intended to make some sense of clinical pictures that can at times seem incomprehensible and to bring to the fore the importance of loss and mourning in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

I thank John Steiner for his wise council during the years of developing this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 According to psychoanalysts, the template for lifelong mourning is developed:

a throughout childhood

b in the womb

c during adolescence

d in the first few years of life

e after losses in childhood.

2 The suggested five stages of mourning are:

a anger, denial, sadness, bargaining, acceptance

b denial, anger, sadness, bargaining, acceptance

c guilt, sadness, denial, loss, acceptance

d numbness, guilt, sadness, loss, acceptance

e denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, acceptance.

3 The most dangerous stage of mourning is:

a denial

b hatred, anger, persecutory guilt and blame

c transition and bargaining

d sadness and neurotic guilt

e acceptance.

4 If only psychotic defences can be used, as in dementia and some forms of schizophrenia, the stage in which arrest in mourning usually occurs is:

a denial

b hatred, anger, persecutory guilt and blame

c transition and bargaining

d sadness and neurotic guilt

e acceptance.

5 The primary psychic defence used in depressive illness is:

a anger turned inwards

b projection

c sublimation

d rationalisation

e humour.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 e 3 b 4 a 5 a

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.