Introduction

Mental imagery and its characteristics

Mental imagery refers to perceptual experiences of a sensory information in the absence of external sensory input, often described as ‘seeing with the mind’s eye’ (Kosslyn et al., Reference Kosslyn, Ganis and Thompson2001). Mental imagery involves all the senses, allows for remembering the past, anticipating the future and making decisions (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Kavanagh, Holmes, MacLeod and Di Simplicio2019). Clinically, mental imagery is characterized by different points: its contents, its vividness, its likelihood and its related emotional effects (type of emotion and valence). Specificities related to the clinical expression of mental images (MI) are prevalent across psychopathology and contribute to patient’s difficulties, especially in emotional, motivational and behavioural domains (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Kavanagh, Holmes, MacLeod and Di Simplicio2019). There is quite a lot of research on imagery in anxiety disorders such as social anxiety (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Clark and Leigh2022; Hackmann et al., Reference Hackmann, Clark and McManus2000) and in unipolar depression (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bonsall, Hales, Mitchell, Renner, Blackwell, Watson, Goodwin and Di Simplicio2016a; Marciniak et al., Reference Marciniak, Shanahan, Binder, Kalisch and Kleim2023). These studies have provided data on the clinical expression of mental imagery and its associations with psychiatric symptoms.

The contents of MI reveal current and specific concerns among healthy individuals and among individuals with psychiatric disorders (Ceschi and Pictet, Reference Ceschi and Pictet2018). In psychopathology, MI contents typically take the form of scenarios that induce behaviours that maintain and reinforce symptoms (Hirsch and Holmes, Reference Hirsch and Holmes2007). For example, individuals with a diagnosis of social anxiety can have MI of themselves experiencing adverse social events (Hackmann et al., Reference Hackmann, Clark and McManus2000). Some individuals with binge eating disorder can have MI of food which are related to more emotional distress than in controls (Dugué et al., Reference Dugué, Keller, Tuschen-Caffier and Jacob2016).

Vividness refers to the clarity with which an individual subjectively perceives a mental image (Sutin and Robins, Reference Sutin and Robins2007). Highly vivid MI are ubiquitous in psychopathology and contribute to the psychological suffering of individuals (Clark and Mackay, Reference Clark and Mackay2015; Connor et al., Reference Connor, Kavanagh, Andrade, May, Feeney, Gullo, White, Fry, Drennan, Previte and Tjondronegoro2014; Hirsch and Holmes, Reference Hirsch and Holmes2007; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Naselaris, Holmes and Kosslyn2015). This also applies to behaviours such as food cravings (Kemps and Tiggemann, Reference Kemps and Tiggemann2015) and suicidality (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Heyes, McManus, Kennerley and Holmes2016).

Another relevant characteristic is the subjective likelihood of events associated with MI (Holmes and Mathews, Reference Holmes and Mathews2005). Imagery is associated with future behaviours by increasing the likelihood of engaging in what is imagined, which is called ‘flashforwards’ (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Crane, Fennell and Williams2007).

Thinking in images is associated with strong emotions such as real-life experiences (Ceschi and Pictet, Reference Ceschi and Pictet2018). These emotional effects of MI are related to their vividness and likelihood (Ceschi and Pictet, Reference Ceschi and Pictet2018). Empirical evidence has shown that mental imagery elicits greater emotional responses than verbal representation of the same information (Holmes and Mathews, Reference Holmes and Mathews2005; Holmes and Mathews, Reference Holmes and Mathews2010; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Heyes, MacLeod and Holmes2016). Therefore, mental imagery is a way to understand emotional disorders and may be useful for psychotherapy (Holmes and Mathews, Reference Holmes and Mathews2010). For example, in anxiety disorders, when individuals with agoraphobia report recurrent MI about past agoraphobic situations, the use of imagery rescripting techniques may be indicated (Day et al., Reference Day, Holmes and Hackmann2004). In unipolar depression, vivid MI related to suicide is known to be a feature of the disorder and a target for treatment (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Shah, Barnhofer and Holmes2012). Mental imagery therefore appears to be a relevant research direction for treating mood instability in bipolar disorders (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Geddes, Colom and Goodwin2008; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Hales, Young and Di Simplicio2019; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Wright, Goodwin, Simon, Morant, Taylor, Brown, Jennings, Hales and Holmes2020; Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Hendrickson, Hales, Voncken and Keijsers2023a).

Mental imagery characteristics in individuals with bipolar disorders

Bipolar disorders (BD) are characterized by mood disturbances, with manic or hypomanic episodes and depressive episodes, separated by periods of euthymia (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). BD counts among the most invalidating psychiatric disorders (World Health Organisation, 2018). The risk of suicide is 15 times higher in individuals with BD than in the general population, with high rates of co–morbid disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Beyond mood instability, emotional dysfunction is a marker of BD, including emotional reactivity, emotion regulation, affect intensity and lability, even during euthymic phases (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Phillips, Leibenluft, M’Bailara, Houenou and Leboyer2012; M’Bailara et al., Reference M’Bailara, Atzeni, Colom, Swendsen, Gard, Desage and Henry2012; Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Kogan, Mennin and Murray2013; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cuellar and Gershon2016a; Wolkenstein et al., Reference Wolkenstein, Zwick, Hautzinger and Joormann2014). Further characterization of emotional disturbances in BD is needed to better understand mood instability (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Tharp, Peckham and McMaster2016b; Lemaire et al., Reference Lemaire, El-Hage and Frangou2015; Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg, Kjaerstad, Burdick, Martinez-Aran, Bonnin, Bowie, Carvalho, Gallagher, Hasler, Lafer, López-Jaramillo, Sumiyoshi, McIntyre, Schaffer, Porter, Purdon, Torres, Yatham and Vieta2019).

To date, little is known about processes involved in individuals with BD emotional disturbances. Mental imagery may be one such contributing factor (Goodwin and Holmes, Reference Goodwin and Holmes2009). In the theoretical model of mental imagery as an emotional amplifier, anxiety and mania would be amplified by the activation of negative and positive MI in individuals with BD (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Geddes, Colom and Goodwin2008). A better understanding of what contributes to anxiety amplification in individuals with BD is essential, as up to 90% of them have a co–morbid anxiety disorder (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, Akiskal, Angst, Greenberg, Hirschfeld, Petukhova and Kessler2007). To synthesize current knowledge about mental imagery in individuals with BD, we conducted a systematic review of literature (Petit et al., Reference Petit, Munuera, Husky and M’Bailara2021). Five cross-sectional studies were found (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010; Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Deeprose, Fairburn, Wallace-Hadrill, Bonsall, Geddes and Goodwin2011; Ivins et al., Reference Ivins, Di Simplicio, Close, Goodwin and Holmes2014). Mental imagery seems to be more vivid, more frequently used and more likely in individuals with BD compared with healthy controls (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Deeprose, Fairburn, Wallace-Hadrill, Bonsall, Geddes and Goodwin2011). Individuals with BD have reported more MI during acute thymic phases than in euthymia (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). MI would also be as frequent and vivid during the acute thymic phases (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). The content of mental imagery would be congruent to thymic phases, current pre-occupations and pushed more individuals with BD to take action than verbal cognition (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010; Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011; Ivins et al., Reference Ivins, Di Simplicio, Close, Goodwin and Holmes2014). A stronger emotional effect of MI in the daily lives of individuals with BD was reported compared with non-clinical controls (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016). The emotional valence related to MI is congruent to mood states in individuals with BD (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016). The types of emotions related to MI were also congruent to mood phases in individuals with BD (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). Taken together, this tends to support the hypothesis of the central role of mental imagery in BD through its emotional effects and its potential impact on mood instability (Goodwin and Holmes, Reference Goodwin and Holmes2009; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Deeprose, Fairburn, Wallace-Hadrill, Bonsall, Geddes and Goodwin2011; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Di Simplicio and Holmes2015). To date, the content of spontaneous MI during the different thymic phases of depression, mania and euthymia and the related clinical characteristics remain unexplored. Such an exploration would reveal whether there is any specificity regarding the content, vividness, likelihood or emotions associated with spontaneous MI. Such data could improve therapeutic targets, especially as existing studies about the use of imagery-based cognitive therapy in individuals with BD showed promising results (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bonsall, Hales, Mitchell, Renner, Blackwell, Watson, Goodwin and Di Simplicio2016a; Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Hendrickson, Hales, Voncken and Keijsers2023a).

The general issue of interpreting the content of emotional mental imagery is in principle complex as it depends highly on personally associated appraisals (Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Voncken, Hendrickson, Di Simplicio, Regeer, Rops and Keijsers2023b). A seemingly neutral image of a window might be associated with a depressed mood as it contains the appraisal that this person is no longer able to paint it himself. The self-rated quality of the image (i.e. vividness and compellingness) and associated appraisals (i.e. metacognitions or likelihood of images and encapsulated beliefs) mediate this effect on emotion and behaviour (Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Voncken, Hendrickson, Houterman and Keijsers2020). Nevertheless, although the interpretation of the content of emotional mental imagery depends highly on personally associated appraisals, the content of mental imagery may also be related to the thymic phases of BD (i.e. mania/hypomania, depression, euthymia). The current study sought to explore the self-reported MI that euthymic individuals with BD experienced during the thymic phases of depression, (hypo)mania and euthymia. The first aim was to extract contents of the self-reported MI that euthymic individuals with BD had experienced during the thymic phases of depression, (hypo)mania and euthymia. The second aim was to describe MI-related characteristics (vividness, likelihood, emotional effects) that euthymic individuals with BD have experienced during the thymic phases of depression, (hypo)mania and euthymia. The last aim was to compare the intensity levels of MI-related characteristics between depression, (hypo)mania and euthymia.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from psychiatric clinics and hospitals in order to improve the representativeness of the sample. The protocol period took place in two different locations (i.e. in a psychiatric hospital and in a psychiatric clinic).

Forty-two individuals diagnosed with BD type I or II according to DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) were recruited from the patients of the clinics and hospitals. Potential participants were approached by their current psychiatrist. Participants were currently in euthymia in order to limit effects of acute mood states. Participants were fluent in French and had current psychiatric care. Participants currently in depression or in (hypo)mania were non-included to the study.

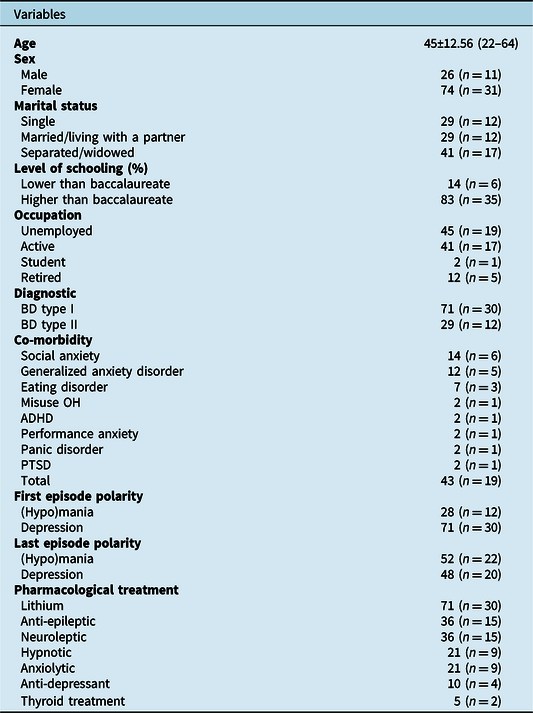

The final sample was 74% female (n=31). The mean age of the sample was 45±12.56 years old (range 22–64). The main psychiatric diagnosis was bipolar disorder type l with 71% of the sample (n=30). A total of 43% of participants (n=19) had co–morbid psychiatric disorders (i.e. social anxiety, GAD, eating disorder, misuse of substances). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

Values represent percentages (frequencies) for categorical attributes and means (SD) (min–max) for continuous attributes.

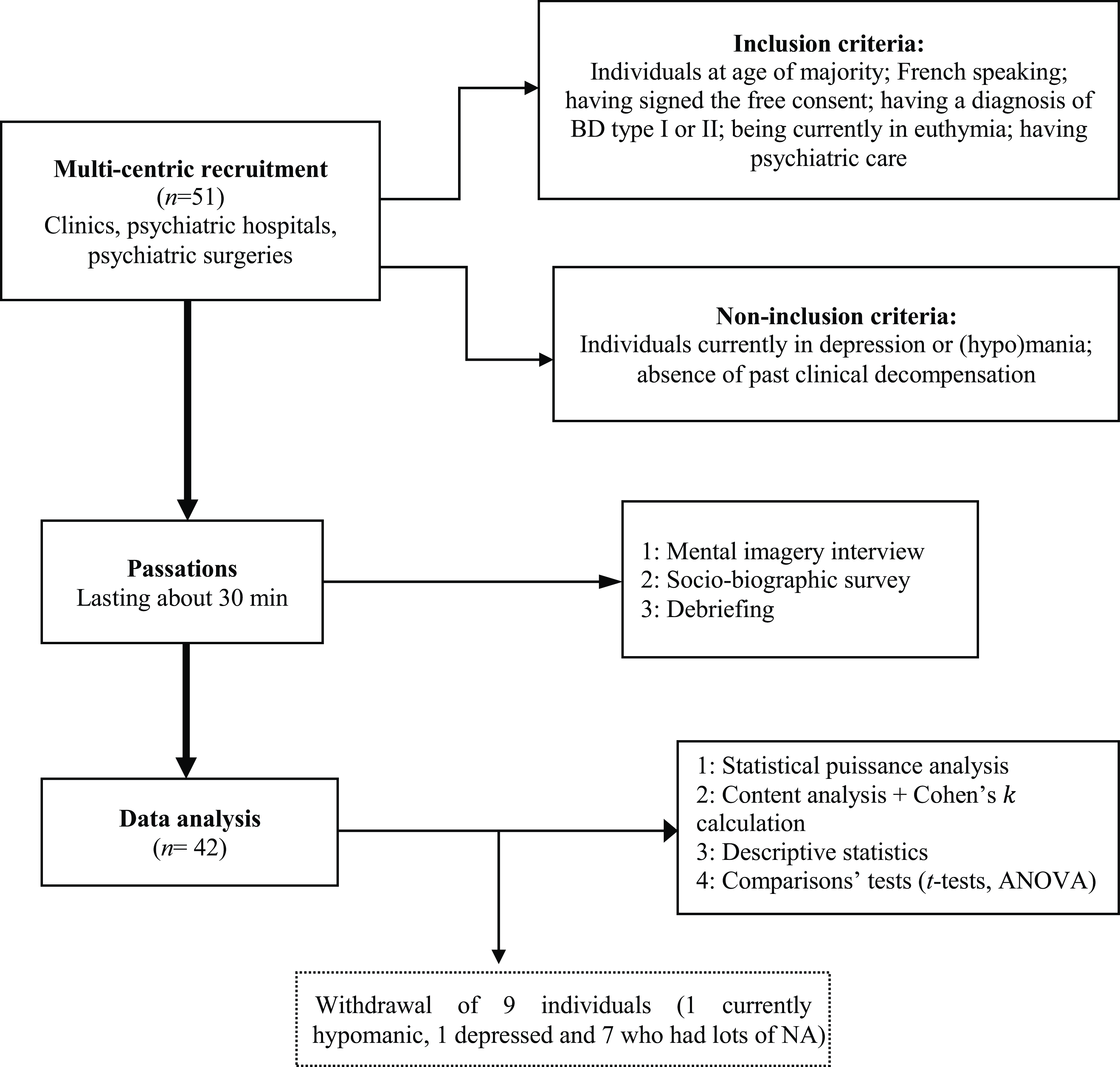

The person with hypomania and the person with depression entered an acute phase between the first contact and the appointment, so their participations were cancelled. The seven individuals with missing data were people who did not have content to report for all the thymic phases of the disorder. Two participants were not included as they were no longer euthymic between the first contact and the study appointment, and seven participants were removed from the analyses due to missing data (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the research procedure. Statistical puissance = Statistical power; Passations = Assessment; ‘NA’ denotes missing data.

Procedure

This study has a cross-sectional and retrospective design. Self-reported MI were assessed using an adaptation of the mental imagery interview (Day et al., Reference Day, Holmes and Hackmann2004). The mental imagery interview explores the content and characteristics of mental images in clinical and non-clinical populations (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Deeprose, Wallace-Hadrill, Heyes and Holmes2013). In the present study, a trained clinician first asked participants to provide examples of MI at times when their mood was most depressed, (hypo)manic and euthymic. The clinician therefore asked each participant to recall a thymic phase (i.e. manic, depressed, euthymic), and then to conjure up a mental image representative of the MI they usually experience during that thymic phase. The participant was asked to describe this image as accurately as possible. Each interview was fully transcribed live. After each evocation of the mental image, the participant was asked to rate the vividness and likelihood of the image. Next, participants were asked to rate the associated and perceived emotional activation: the intensity of pleasure, displeasure and the type of emotions associated with each mental image. Finally, the participants were asked to complete the socio-demographic and clinical questionnaires. A debriefing time was offered to the participants. In case of high emotional activation, the trained clinician was able to use emotional stabilization techniques. The whole procedure took about one hour (see Fig. 1).

Materials

The operationalization of a mental imagery clinical characteristic in one item is extracted from adaptations of the mental imagery interview (e.g. Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011). The assessment of mental imagery clinical characteristics (i.e. vividness, likelihood, emotion) was self-reported.

The degree of vividness of each reported mental image was rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely); the higher the score, the more vivid the image.

The level of likelihood associated with each mental image was assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 9 (extremely); the higher the score, the more likely the mental image is considered to occur in real life.

Previous studies have focused on either emotional valence or type of emotions (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). The intensity of pleasure and the intensity of displeasure related to each mental image were assessed on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 8 (extremely). For the intensity of pleasure related to the image, the higher the score, the more the participant reports feeling a very pleasant emotion when this mental image is activated. Conversely, for the intensity of the displeasure related to the image, the higher the score, the more the participant reports feeling a very unpleasant emotion when this mental image is activated. In addition to valence and arousal, we also assessed each primary emotion associated with the mental image. Participants were asked to indicate the emotion(s) associated with the self-reported mental image. Participants could choose one or more emotions (i.e. joy, sadness, anger, disgust, surprise, no emotion, other emotions). Participants were asked to rate the intensity of each emotion using a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 8 (extremely).

Data analysis

The sample size was defined a priori using statistical puissance analysis with G*Power software. Thirty-nine participants were required to achieve a statistical power of 95% with an effect size of 0.30 in an analysis of variance (ANOVA). One hundred and eight participants were required to achieve a statistical power of 95% with an effect size of 0.30 in t-tests. Next, a content analysis was performed to extract the themes associated with each thymic phase. An independent assessment of the content of the images was then carried out. Two researchers independently coded the data for reliability. Two clinicians were involved to confirm or reject the validity of these assessments. The overall level of agreement between the first two raters was calculated using Cohen’s kappa which is useful for reliability. Coding discrepancies between raters were discussed and the final categories were validated. Descriptive statistical analysis of the sample’s clinical and socio-biographic variables were carried out for a better characterization of participants; t-tests were performed to compare MI-related characteristics within each thymic phase. The same process was used for MI-related intensity levels of pleasure and displeasure with additional comparative analyses between thymic phases using ANOVA. All quantitative analyses were performed using RStudio software.

Results

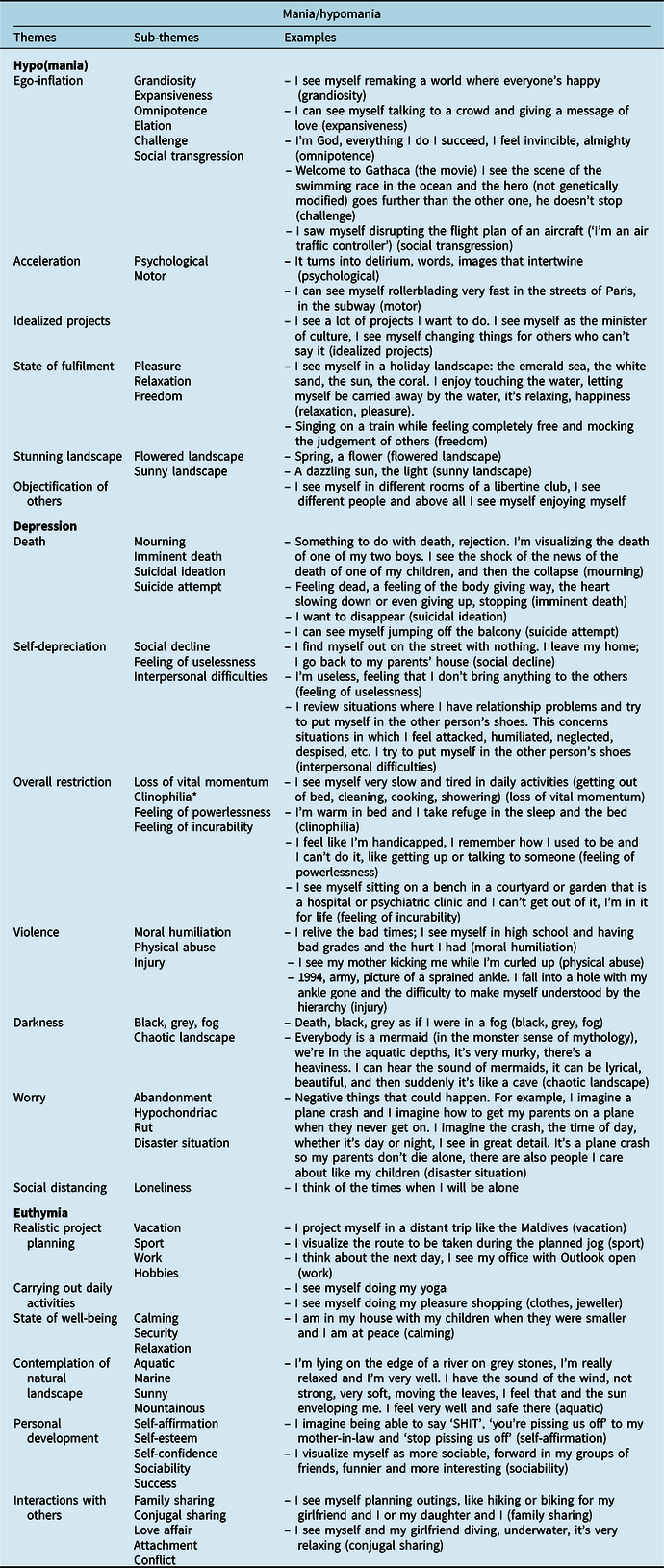

The final sample consisted of 122 scenarios (i.e. 40 scenarios associated with mania or hypomania, 40 with depression and 42 with euthymia). Two scenarios were missing in mania/hypomania. A high level of overall agreement was obtained between raters (Cohen’s k=0.68, range: 0.22–1.00). The details of the contents are presented in Table 2. The characteristics of the MI are reported in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2. Contents related to the mental images in (hypo)mania, depression and euthymia

* Clinophilia is the tendency to remain in bed in a reclined position without sleeping for prolonged periods of time.

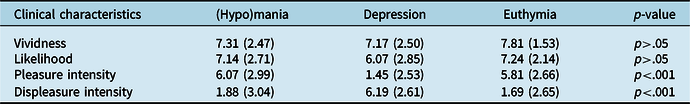

Table 3. Mental images characteristics across mood states

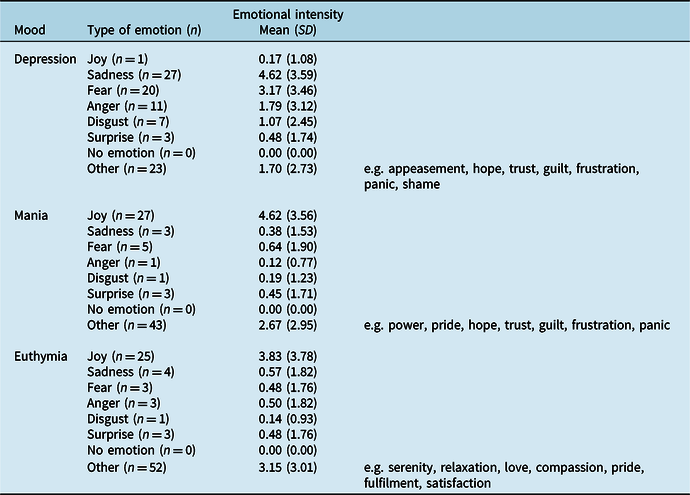

Table 4. Type of emotions associated with mental images inside each thymic phase and their levels of intensity

Mental imagery content and characteristics in (hypo)mania

The content analysis extracted six themes associated with (hypo)mania (see Table 2). The MI related to (hypo)mania were about ego-inflation, with an elevation of self-confidence and grandiosity (i.e. grandiosity, expansiveness, omnipotence, elation, challenge, social transgression), acceleration (i.e. psychological, motor), idealized projects, state of fulfilment (i.e. pleasure, relaxation, freedom), stunning landscapes (i.e. flowered landscape, sunny landscape) and objectification of others.

The contents of MI in (hypo)mania were equally very vivid and very likely (W(41)=113; p>.05). The intensity of pleasure was significantly higher than the intensity of displeasure (W(41)=602.5; p<.001; d=0.78). (Hypo)manic MI mainly induced other emotions (n=43) with a low level of intensity (mean 2.67±2.95) and joy (n=27) with a moderate level of intensity (mean 4.62±3.56).

Content and characteristics of mental imagery in depression

The content analysis extracted seven themes associated with depression (see Table 2). The MI related to depression were about death (i.e. mourning, imminent death, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt), self-depreciation (i.e. social decline, feeling of uselessness, interpersonal difficulties), overall restriction (loss of vital momentum, clinophilia, feeling of powerlessness, feeling of incurability), violence (i.e. moral humiliation, physical abuse, injury), darkness (i.e. black, grey, fog, chaotic landscapes), worry (i.e. anxiety of abandonment, hypochondria, rut, disaster situation) and social distancing (i.e. loneliness).

The contents of MI in depression were extremely vivid and moderately likely with a significant difference of intensity level between the two characteristics (W(41)=325; p<.05; d=0.24). Depression-related MI were associated with a low pleasure intensity and a high level of intensity of displeasure. The level of intensity of displeasure was significantly higher than the intensity of pleasure (W(41)=48; p<.001; d=–1.05). Depressive MI were related to sadness (n=27) with a moderate level of intensity (mean 4.62±3.59), to other emotions (n=23) with a low level of intensity (mean 1.70±2.73), to fear (n=20) with a moderate level of intensity (mean 3.17±3.46) and to anger (n=1) with a low level of intensity (mean 1.79±3.12).

Mental imagery content and characteristics in euthymia

The content analysis extracted six themes associated with euthymia (see Table 2). MI related to euthymia were about realistic project planning (i.e. vacation, sport, work, hobbies), carrying out daily activities, state of well-being (i.e. calm, security, relaxation), contemplation of natural landscapes (i.e. aquatic, marine, sunny, mountainous), personal development (i.e. self-affirmation, self-esteem, self-confidence, sociability, success) and interactions with others (i.e. family sharing, conjugal sharing, love affair, attachment, conflict).

The contents of MI in euthymia were equally very vivid and very likely (W(41)=97; p>.05). The intensity of pleasure was significantly higher than displeasure intensity (W(41)=727.5; p<.001; d=0.82). Pleasure intensity was extremely high and displeasure intensity was low in euthymia. Euthymic MI aroused mostly other emotions (n=52) with a moderate level of intensity (mean 3.15±3.01) and joy (n=25) with a moderate level of intensity (mean 3.83±3.78).

Mental imagery characteristics in (hypo)mania vs depression vs euthymia

One-way ANOVA indicated that there was a significant effect of the thymic phase on the intensity of pleasure associated with MI (χ2(2,41)=43.304; p<.001; η2G=0.38). There was a significant difference between depression and (hypo)mania (p<.001) and between depression and euthymia (p<.001). One-factor analysis of variance indicated that there was a significant effect of the thymic phase on the intensity of displeasure associated with MI (χ2(2,N=9)=35.496; p<.001; d=0.37). A significant difference was found between depression and (hypo)mania (p<.001) and between depression and euthymia (p<.001).

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the content of MI that euthymic individuals with BD experienced during (hypo)mania, depression and euthymia as well as related clinical characteristics (i.e. vividness, likelihood, emotional effects).

The MI related to (hypo)mania are consistent with DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria for mania (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organisation, 2000; World Health Organisation, 2018). The results are also consistent with a recent factor analysis on the structure of mania (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Valerio and Parker2020). The people depicted in the (hypo)manic images appear reified, as they are only present in the scenario to serve the participant’s interest and have no particular identity. To the best of our knowledge, the present results are the first to describe the phenomenological aspects of (hypo)mania through MI, as has been done for anxiety disorders as an example (Hirsch and Holmes, Reference Hirsch and Holmes2007). The MI related to depression are consistent with Beck’s cognitive triad (Beck and Rush, 1979) with a negative vision of the self, others and the world. The set of themes extracted is in line with the mental imagery of unipolar depression, characterized by negative MI and impoverished positive MI (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Blackwell, Burnett Heyes, Renner and Raes2016b; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Holmes, MacLeod and Murphy2018). The content on death indicates that mental imagery of suicide is a critical feature of suicidality in individuals with BD (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011) as it is in unipolar depression (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Shah, Barnhofer and Holmes2012). The themes of ‘death’, ‘self-depreciation’ and the sub-themes of ‘general restriction’ are consistent with DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria for depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organisation, 2018). The theme of worry can be explained by an increased prevalence of anxiety disorders in BD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Themes about violence may reveal that depression-related MI in individuals with BD reactivates past traumatic experiences. These findings support a growing literature showing the importance of trauma in individuals with BD (Aas et al., Reference Aas, Henry, Andreassen, Bellivier, Melle and Etain2016; Dualibe and Osório, Reference Dualibe and Osório2017; Etain et al., Reference Etain, Aas, Andreassen, Lorentzen, Dieset, Gard, Kahn, Bellivier, Leboyer, Melle and Henry2013; Farias et al., Reference Farias, Cardoso, Mondin, Souza, da Silva, Kapczinski, Magalhães and Jansen2019) and specifically in bipolar depression (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cuellar and Gershon2016a). Depression-related MI appears to be more diverse in individuals with BD compared with previous results stating that they were focused on death and suicide (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). The MI related to euthymia were generally about mood stabilization and well-being. The mental landscape of individuals with BD focuses on the planning and realization of non-idealized projects. Psychological availability to others and to the environment seems to be more accessible than in the acute thymic phases. Overall, a more balanced relationship between the self and the outside world than in depression and (hypo)mania seems to be depicted.

Exploring clinical characteristics related to the contents of MI reveals what the person is experiencing at the time these images are activated. The high levels of vividness of MI are consistent with previous studies that showed higher vividness levels in individuals with BD compared with control individuals (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Deeprose, Fairburn, Wallace-Hadrill, Bonsall, Geddes and Goodwin2011) and to individuals with unipolar depression (Ivins et al., Reference Ivins, Di Simplicio, Close, Goodwin and Holmes2014). The self-reported likelihood of the MI occurring in real life is also high, except in depression where it is moderate. MI might be perceived as more achievable in (hypo)mania and euthymia than in depression. Nevertheless, a previous study showed that MI related to suicide were more compelling in individuals with BD than in individuals with unipolar depression (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011). It was also found that individuals with BD were more than twice as likely to report that MI prompted them to act to complete suicide (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Deeprose, Goodwin and Holmes2011). Another study showed that mental imagery of depression was more distressing and had a stronger impact in individuals with BD in their daily lives than MI related to hypomania (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010).

The activation of MI in individuals with BD is also related to an emotional experience. When comparing the MI of the different thymic phases with each other, the level of pleasure was higher in (hypo)mania than in depression and was also higher in euthymia compared with depression. There was no difference between (hypo)mania and euthymia with regard to the level of pleasure. The intensity of displeasure was higher in depression than in euthymia and in (hypo)mania. The type of emotions related to the self-reported MI shows that some of them are common across the thymic phases and others are specifically related to each of them, as was found in another study (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). As in previous studies, there is a congruence between MI-related emotional valence and mood (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016) but also between the type of MI-related emotion and mood in individuals with BD (Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Brewin, Mansell and Donaldson2010). This supports the hypothesis that MI-related emotions are related to the polarity of mood switch in individuals with BD (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Di Simplicio and Holmes2015). These results are consistent with the theoretical model of mental imagery in individuals with BD, which assumes that imagery is an emotional amplifier and contributes to mood and emotional disturbance (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Geddes, Colom and Goodwin2008; Goodwin and Holmes, Reference Goodwin and Holmes2009).

Activation of mental imagery during euthymia could be a therapeutic tool to prevent thymic relapse. The results showed that the activation of spontaneous MI that individuals with BD experienced in the past has specific effects in the present moment, depending on whether the images are related to (hypo)mania, depression, or to euthymia. The identification of these contents of MI and their related clinical characteristics supports the relevance of using imagery-focused cognitive therapy (ImCT) techniques to work on affective regulation in euthymic individuals with BD. To date, ImCT has been used in cognitive behavioural therapy settings (Hackmann et al., Reference Hackmann, Bennett-Levy and Holmes2011). ImCT aims to reduce negative imagery and promote positive imagery by acting directly or indirectly on the images (Ceschi and Pictet, Reference Ceschi and Pictet2018). ImCT techniques includes imagery rescripting techniques (to transform distressing imagery into more functional imagery), positive imagery strategies (learning to promote pleasant imagery), completing tasks (using activities to alleviate distressing imagery) or metacognitive strategies (learning to step back from problematic imagery) (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018). ImCT protocols exist for various psychiatric disorders such as unipolar depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (Blackwell et al., Reference Blackwell, Browning, Mathews, Pictet, Welch, Davies and Holmes2015; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000). The relevance of ImCT for individuals with BD is supported by a growing literature targeting mood instability and anxiety through work on the characteristics of MI (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bonsall, Hales, Mitchell, Renner, Blackwell, Watson, Goodwin and Di Simplicio2016a; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Hales, Young and Di Simplicio2019; Iyadurai et al., Reference Iyadurai, Hales, Blackwell, Young and Holmes2020; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Wright, Goodwin, Simon, Morant, Taylor, Brown, Jennings, Hales and Holmes2020; Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Hendrickson, Hales, Voncken and Keijsers2023a). Existing data support the feasibility of this practice among individuals with BD (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Wright, Goodwin, Simon, Morant, Taylor, Brown, Jennings, Hales and Holmes2020). Recent findings have shown that ImCT can help to improve depression, mania, anxiety, functioning and hope in individuals with BD (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Di Simplicio, Iyadurai, Blackwell, Young, Fairburn, Geddes, Goodwin and Holmes2018; Van Den Berg et al., Reference Van Den Berg, Hendrickson, Hales, Voncken and Keijsers2023a).

Limitations

The small sample size and the resulting low statistical power limit the generalization of the results. The representativeness of individuals with BD is limited by the characteristics of the sample and a selection bias might be present in our recruitment. The final sample was unbalanced with regard to gender and co–morbidities, with more women than men and significant levels of co–morbid anxiety disorders. The cross-sectional design of the study has risks of bias according to the pyramid of hierarchy of evidence (Yetley et al., Reference Yetley, MacFarlane, Greene-Finestone, Garza, Ard, Atkinson, Bier, Carriquiry, Harlan, Hattis, King, Krewski, O’Connor, Prentice, Rodricks and Wells2017). The use of a retrospective design may have induced recall bias when participants had to describe their MI in acute thymic states. In addition, there was no assessment of a participant’s current mood states. Order-related bias could also be present due to an absence of counterbalancing. In the absence of psychometric validation of the tools used to assess MI, the choice of thresholds was arbitrary. As there is no consensus throughout literature on the characteristics of MI that should be assessed, not all of them were considered in this research.

Perspectives and implications

The present study should be replicated with a larger total sample in order to strengthen the validity of the results and reduce methodological bias. As current mood states may influence remembered mental images, additional assessments of depressive, (hypo)manic and anxious symptoms would be useful. Comparisons with other clinical populations would help to see whether these findings are disorder-specific or not. Psychometric validation of the tools used to assess MI-related emotional activation is also needed. In addition, a consensus on the characteristics of mental imagery that are essential to measure in psychopathology is required. Future studies should add physiological measures of emotion to strengthen the validity of measures of emotional activation related to mental imagery.

This research has provided data on the characteristics associated with MI contents in individuals with BD. We now have a preliminary insight into the mental landscape of individuals with BD. This is important because individuals with BD are reported to think more images than in words (Di Simplicio et al., Reference Di Simplicio, Renner, Blackwell, Mitchell, Stratford, Watson, Myers, Nobre, Lau-Zhu and Holmes2016; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Deeprose, Fairburn, Wallace-Hadrill, Bonsall, Geddes and Goodwin2011; Ivins et al., Reference Ivins, Di Simplicio, Close, Goodwin and Holmes2014). Our study also shows that mental imagery is a relevant psychological process to work on emotional disturbances in this clinical population during euthymia. The content of mental imagery may be involved in the affective dysfunction of individuals with BD through its vividness, likelihood and subsequent emotional activation. These emotional effects of mental imagery appear to offer a therapeutic opportunity to target mood instability and thymic relapse during euthymia. Thus, the present findings add new clinical information for the use of imagery-based cognitive therapy with people with BD.

Conclusions

The present findings provide further support for considering mental imagery as a contributing process to the affective disturbances of individuals with BD. These data about the spontaneous contents of MI reported across the thymic phases of (hypo)mania, depression and euthymia reveal phenomenological aspects of BD. The present study should be replicated to strengthen the validity of results, taking into account the methodological limitations cited above. Exploring the contents of MI and their related characteristics could be relevant in imagery-based cognitive therapy to prevent thymic relapse in individuals with BD.

Data availability statement

The information needed to reproduce all of the reported results is available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/U9ZSX

Acknowledgements

We thank Doctor Marion Lenoir (Clinique Béthanie, France), Doctor François Chevrier and the team of the Centre Ressource Bipolaire Sud Aquitaine (Clinique Psychiatrique Château Caradoc, Bayonne, France) and Doctor Sébastien Gard and the team of Centre expert Bipolaire (Pôle PGU, Hôpital Charles Perrens, Bordeaux, France) for their help in the recruitment of participants. We sincerely thank Isabelle Minois and Léa Zanouy for their help in conducting the content analysis.

Author contributions

Katia M’Bailara: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Supervision (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Fanny Echegaray: Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Resources (equal), Software (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Martina Di Simplicio: Conceptualization (lead), Methodology (lead), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The paper complied with APA ethical standards in the treatment of participants, and with the relevant Institutional Review Board. Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors have seen the submission in full and agreed to it going forward for publication. This study was approved by a French Ethical Committee. This study respects the right to privacy of the participants. All patients read the information letter. Informed consent was obtained.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.