1. Introduction

Customary practices that operate independently of state law have been a central focus of research in the sociology of law (Ehrlich, Reference Ehrlich1913; Ellickson, Reference Ellickson1991; Qiao, Reference Qiao2017). Land use customs, in particular, have garnered significant attention because they are often perceived as obstacles to economic development and are in conflict with state laws (van Meijl and von Benda-Beckham, Reference van Meijl and von Benda-Beckham1999). The practice of customary farmland reallocation (CFR) in China, which this paper examines, is similarly viewed as a barrier to economic development and is prohibited by Chinese state law.

This practice is not an ancient custom but rather a remnant of land ownership collectivization from the era of the People’s Commune (Renmin Gongshe). Although it was officially prohibited in 2002, it has persisted for a long time. Recent legal reforms aim to eliminate such practices and reinforce the protection of farmland property rights. However, a significant gap remains between the objectives of state laws and the actual practices, or living law, in rural areas. Why does a relatively recent customary practice continue to persist despite being prohibited? This paper explores this question, with a particular focus on the role of legal knowledge.

The acceptance of laws in rural areas is a crucial prerequisite for studying their effectiveness. Whether the expectations and objectives of legislators can be effectively implemented in rural society depends on the grassroots understanding of these external statutes. Therefore, this study focuses on the acceptance of the Rural Land Contract Law (RLCL) in rural China and analyses the impact of legal knowledge on farmland customs.

The RLCL is one of the most important laws governing agricultural land in China. It systematically establishes the Household Responsibility System (HRS), which grants households the right to use farmland and protects this right for a long period. The HRS comes from China’s experience after two decades of institutional exploration on farmland. Originating from grassroots practices in Xiaogang Village, Anhui Province, the HRS is an innovative model of collective land ownership between state-owned and privately owned systems, which was part of the agricultural reform during the Reform and Opening-up period. HRS satisfies farmers’ desire for private possession of agricultural output and significantly incentivizes farmers’ productivity.

However, in rural China, alongside the establishment of the HRS, the CFR has gradually emerged. CFR refers to the customary practice where the village periodically reclaims farmland and reallocates it to households in proportion to their population. CFR is an egalitarian practice where farmland is periodically reallocated due to changes in household populations (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2022, p. 336). CFR addresses the issue of newly added populations lacking farmland in the village. Additionally, CFR is intricately connected to the egalitarian ideals of the people’s commune era. However, this practice contradicts the protection of property rights in farmland that the RLCL aims to promote.

Promulgated in 2002, the RLCL clarifies land property rights and delineates the responsibilities and rights of the contracting parties. The RLCL aims to promote a system where farmers who no longer use their farmland themselves are encouraged to rent it out, for a fee, to other farmers seeking to expand their agricultural operations. By protecting the property rights to lease out and lease in farmland, this law seeks to rationalize farmland use in rural areas. Therefore, this law prohibited CFR and helps mitigate the risks associated with the agricultural land transfer, ensures fair agreements, protects farmers’ rights, and promotes rural development and stability (Deininger, Reference Deininger2003, p.1220; Zhao, Reference Zhao2020). After two decades of policy changes, both supporting and opposing CFR, the RLCL became the first state law to explicitly prohibit CFR. This prohibition has been upheld in subsequent amendments to this law and remains in effect today.

This prohibition means that the practice of regularly reclaiming and reallocating contracted farmland within villages is no longer legal, enhancing the security of land tenure (Deininger and Jin, Reference Deininger and Jin2009, p. 36). In areas where the law achieved its intended outcomes, farmers with insufficient farmland to sustain themselves were able to retain their rural household registration (Hukou) while leasing out their land and taking on temporary urban employment, thus increasing their net income. Meanwhile, farmers wishing to expand their agricultural operations were able to lease this available farmland (Zhao, Reference Zhao2020).

Despite the promulgation of the RLCL, the CFR has not disappeared. The CFR, which emerged alongside the HRS, involves villages periodically reclaiming and reallocating farmland (Che, Reference Che2014, p. 20; Yan, Bauer and Huo, Reference Yan, Bauer and Huo2014, p. 312). This practice is seen as an extension of collective ownership, aiming to maintain equity by evenly distributing farmland per capita within the village (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Huang, Li and Rozelle2002, p. 88; Kong and Unger, Reference Kong and Unger2013, p. 18). However, it undermines the security of land tenure and creates a grey area of power, causing concern for the central government, which ultimately prohibited it in the 2002 RLCL. The spread of the law is influenced by farmers’ awareness, willingness, and psychological identity, making its effectiveness difficult to gauge. Investigations conducted by researchers Feng, Bao and Jiang (Reference Feng, Tan, Zhang, Zhang, Pan, Qu, Smith, Li and Zhang2011) indicate that although some villages have stopped the CFR, many rural regions still maintain this practice.

This paper explores the relationship between legal knowledge of the RLCL and CFR. Unlike studies that consider the law as a whole, this paper analyses villagers’ understanding of different aspects of the law and how this legal knowledge relates to their attitudes towards CFR. Specifically, this study aims to answer the following questions: Do villagers know about RLCL? Is there variation in villagers’ legal knowledge of different aspects of the RLCL? Is there a significant relationship between RLCL and attitudes towards CFR?

By addressing these questions, this paper aims to shed light on why the RLCL may not be as widely known among villagers as lawmakers anticipated and to explore why legislation has not fully eliminated CFR. The gap between the enactment of laws and their practical understanding—where individuals interpret the same law differently—has been well documented in previous research (Chen and Hanson, Reference Chen and Hanson2004, p. 1207). Further, there is limited understanding of how a single individual may interpret various aspects (or dimensions) of the same law differently. Therefore, this paper aims to clarify whether there are differences in villagers’ legal knowledge of different aspects or dimensions of the RLCL and to explore the relationship between these differences and their attitudes towards CFR. Through the case study, this paper aims to address the issue of CFR from a legal perspective by demonstrating that the RLCL may not be well understood and by highlighting the importance of effectively popularizing the RLCL. In the context of China’s ongoing promotion of the HRS, understanding the impact of legal knowledge and villagers’ responses is crucial for successful policy implementation.

The structure of this paper is as follows: First, a literature review will be conducted to examine previous research on legal knowledge and the CFR. Second, the research methodology will be presented, detailing the study site, data collection, and analysis methods. Third, the results will be presented, analysing the relationship between legal knowledge and the CFR. Finally, the discussion will explore the significance and limitations of the findings and propose directions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Legal knowledge, attitude, and consciousness

In the sociology of law, research has primarily focused on legal consciousness rather than legal knowledge (Hertogh, Reference Hertogh2018). Legal consciousness refers to the combination of an individual’s law-related knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs, and values (Horák, Lacko and Klocek, Reference Horák, Lacko and Klocek2021). In Japan, which imported Western modern law, studies have concentrated on whether citizens possess a modern legal consciousness that aligns with modern law, rather than on their detailed knowledge of laws (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima1974; Miyazawa, Reference Miyazawa1987). In the United States, criticisms of legal consciousness research that measures the effectiveness of state law have led to a shift towards studying legal consciousness based on people’s everyday sense of justice rather than strictly adhering to state law (Silbey, Reference Silbey2005). In contrast, the context of China offers unique challenges. The transition from a planned economy to a market economy has resulted in a relatively short history of legal system development, leading to a limited understanding of legal practices. While this paper primarily investigates the role of legal knowledge—particularly in rural areas where access to legal resources is constrained—it also adopts a broader perspective on legal consciousness. This includes examining people’s attitudes towards the interaction between national laws, local social norms, and trust in alternative social rules. By integrating available data, this paper analyses the interplay among legal knowledge, values, and social pressures to provide insights into the development of legal consciousness. Specifically, it seeks to understand how legal knowledge shapes people’s negotiation between customary practices and national laws. This approach allows for a more nuanced exploration of legal consciousness in rural China, addressing not only the dissemination of legal knowledge but also its integration with broader social and cultural dynamics.

The penetration of legal knowledge in rural China is less than ideal. Previous studies indicate that legal knowledge plays a critical role in compliance and behaviour shaping (Tobia, Reference Tobia2024). Effective laws require individuals to understand and interpret the legal system (Peczenik and Hage, Reference Peczenik and Hage2000, pp. 343–4), but ignorance and misunderstanding of legal rules are widespread. At the individual level, legal knowledge in rural China is often influenced by relationships with extended family, community members, and political elites (Li, Reference Li2016, p. 948). Additionally, there are challenges in building legal education institutions and human resources (Cao, Reference Cao2022, p. 115). Structural limitations imposed by the Household Registration System (Hukou) make private legal services in rural areas temporary, expensive, and unsustainable. Fu (Reference Fu2013, p. 129) and Pia (Reference Pia2016, pp. 227–8) argue that rural China is in a state of “vacuum,” where shared morals have not yet been restored, and laws are rarely seen. The above research makes the question of whether RLCL is able to reach the rural areas and work as expected by the lawmakers a question that needs to be revisited.

On the other hand, the positive impact of legal knowledge in rural China is also expected. Despite traditional rural communities’ resistance to legal intervention, studies have found that public legal education positively influences local legal order by enabling the public to identify with the content of the legal provisions (Zhang, Messner and Lu, Reference Zhang, Messner and Lu1999, p. 446). The spread of legal knowledge encourages residents to use formal legal institutions to handle economic disputes (Shen and Wang, Reference Shen and Wang2009, p. 118). Moreover, the spread of legal knowledge within families can ultimately promote agricultural production as increased security of tenure stimulates farmers to invest in farmland (Che and Zhang, Reference Che and Zhang2017, p. 159).

In addition to knowledge, attitudes and consciousness are also focal points in legal research. While knowledge pertains to individuals’ understanding of legal texts, procedures, and systems, attitudes and broader legal consciousness involve people’s comprehension, attitudes, acceptance, and perceptions of justice regarding the law (Silbey, Reference Silbey2005, p. 360; Chua and Engel, Reference Chua and Engel2019, p. 349). In this paper, we distinguish between legal knowledge and legal consciousness as follows: legal knowledge refers to whether one knows the content of specific laws, while legal consciousness means perceiving the legal order that laws aim to protect as legitimate, even without knowing the specific content of those laws. They are not mutually exclusive. As shown in the 1999 study by Zhang, Messner, and Lu, public legal education entails not only the spread of legal knowledge but also fostering public legal consciousness (Reference Zhang, Messner and Lu1999, p. 446).

Although attitudes may not fully reflect the actual effectiveness of law implementation—since they can be influenced by culture, customs, personal experiences, and other factors that may not directly impact law enforcement—legal knowledge can ensure that villagers understand their rights and obligations, thereby enhancing legal compliance. Even if there are divergent attitudes towards the law among villagers, possessing sufficient legal knowledge allows them to correctly implement legal provisions in practice. Therefore, this study prioritizes legal knowledge as a primary consideration.

2.2. Household responsibility system and customary farmland reallocation

Decollectivization is a pivotal characteristic in transforming China’s farmland system. Before 1978, agricultural land was controlled by collectivized farms, where households lacked autonomy in production decisions and output allocations. Despite its egalitarian principles, collectivization led to a decline in agricultural productivity.

In 1979, as part of the broader Reform and Opening-up policy, the HRS was introduced and fully implemented by 1983. This reform transferred ownership of agricultural land from the People’s Commune (Renmin Gongshe) to the villages while retaining collective ownership. The village leased farmland to the farmers for 15 years (Chengbao Jingying Quan), allowing them to make independent production decisions and manage the proceeds.

The 1998 Land Management Law extended the tenure to 30 years, encouraging long-term farmland investments. As mentioned earlier, the 2002 Rural Land Contracting Law prohibited the practice of land reallocation, protected each household’s land use rights for extended periods, and allowed for land leasing, aiming to promote land mobility. The 2007 Property Law further clarified these points.

In 2014, the Three Rights Separation Policy (Sanquan Fenzhi Zhengce) separated and protected three rights related to farmland: ownership rights, contracted rights, and management rights. While villages retain land ownership, households’ contracted rights to farmland were further strengthened. Households that are not actively farming can lease out their land by separating management rights from their contracted rights, enabling them to earn rent without forfeiting their contracted rights. With management rights also legally protected, farmers or enterprises leasing land can confidently expand their operations. In 2019, the Chinese State Council extended the validity of contracted rights tenure by an additional 30 years, providing automatic renewal without renegotiation. This policy, often referred to as the propertization of farmland, aims to foster stability and longevity in farmland property rights, acknowledging farmers as the backbone of agricultural production and safeguarding their rights.

Therefore, given the implementation of laws oriented towards propertization, there should no longer be room for CFR to persist. However, despite this, the practice of periodically returning household’s contracted rights to the village and reallocating farmland according to each household’s population continues.

Brown argued that in early modern Japan, farmland reallocation was driven by the need to equalize cultivation conditions in response to frequent natural disasters (Brown, Reference Brown2011). However, in rural China, where flatlands are less susceptible to disasters, reallocation was carried out based on the principle that farmland should be reallocated equally according to household size.

The village’s collective ownership has a theoretical flaw: how to manage changes in population. If everyone holds equal rights, fairly reallocating resources becomes challenging when the population increases or decreases. New members may demand the same resources as existing members, while a population decrease could necessitate reallocating resources. Despite this challenge, an informal practice known as CFR has emerged. Villages often terminate existing contracted rights prematurely and initiate new tenures when there are changes in membership. According to Feng et al., 79.9% of respondents surveyed in 1999 reported experiencing CFR (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Tan, Zhang, Zhang, Pan, Qu, Smith, Li and Zhang2011, p. 563).

Policies and laws have been enacted to address CFR. Initially, CFR was tolerated to maintain stability, but it was prohibited in 1997, only to be tolerated again under stable conditions in 1998. The 2002 RLCL officially prohibited CFR, allowing it only under specific circumstances, such as with the majority consent of villagers and government approval, particularly in the aftermath of severe natural disasters. Despite these measures, CFR persists. In a survey from Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Liaoning provinces, 24.4% of respondents reported encountering CFR, with the highest incidence in Jiangxi at 45.2% (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Antonides, Heerink, Zhu and Ma2022, p. 12).

2.3. The relationship between legal knowledge and customary farmland reallocation

Many studies hold confidence that RLCL reduces the probability of CFR occurrence. On one hand, legal knowledge can enhance Chinese farmers’ ability to cope with the instability of land tenure and increase food production (Che and Zhang, Reference Che and Zhang2017, p. 159). In villages practising CFR, unstable tenure inhibits the outflow of agricultural labour, while the land certificate (Jiti Tudi Suoyou Zheng) helps secure land tenure and encourages farmers to seek non-agricultural employment opportunities (Deininger et al., Reference Deininger, Jin, Xia and Huang2014, p. 515; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2019, p. 1412). The RLCL’s protection of legal land transfers increases land-leasing activities, leasing the land to more productive farmers and improving agricultural efficiency through formal land transfers (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Liu, Wang and Wang2021, p. 1860). Additionally, a report shows that holding the land certificate positively impacts land subleasing to non-relatives (Wang, Riedinger and Jin, Reference Wang, Riedinger and Jin2012). Nevertheless, concerns have been raised about the potential negative impacts of reducing CFR. Wang et al. reported that over 60% of farmers opposed the central government’s farmland policies (Reference Wang, Tong, Su, Wei and Tao2011, p. 813). While land reallocation might contribute to greater equity among rural households, it also risks dampening incentives for long-term agricultural investment. Similarly, Zhao found that abolishing CFR resulted in a 7% increase in non-agricultural employment and a 6.5% rise in per capita household income (Reference Zhao2020, p. 17). However, these benefits were accompanied by a 6% decline in total agricultural output and a significant increase in income inequality within villages, indicating that reducing CFR is not a universally optimal solution. Ma et al. further suggested that in regions lacking alternative sources of social security, reallocating farmland based on population dynamics serves as an essential mechanism to ensure that all households have sufficient land to sustain their livelihoods (Reference Ma, Heerink, Feng and Shi2015, p. 304). These cautious perspectives reflect a shared prudence, emphasizing that while rural land titling may be a future inevitability, hasty implementation of such reforms may not yield the intended outcomes. In contrast, the optimistic perspectives discussed earlier currently dominate policy discourse in China.

Villagers’ legal knowledge of the RLCL is expected to be associated with lower levels of CFR. Deininger and Jin noted that village leaders knowledgeable about RLCL were associated with a lower likelihood of CFR (Reference Deininger and Jin2009, p. 36). Conversely, areas highly dependent on agriculture were more likely to experience reallocation.

Contrary to Deininger and Jin, Ren et al. argued that having legal knowledge actually leads to the continuation of CFR through a survey of four provinces in China (Deininger and Jin, Reference Deininger and Jin2009, p. 36; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2022, p. 1412). Ren et al. (Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2022) attribute the plausible reason to the fact that the more familiar the households are with the RLCL, the more likely they are to also be aware of the exception provisions therein and use them as a basis for CFR. However, some studies highlight the limitations of legal knowledge’s influence. For instance, Hong et al. argue that the effectiveness of the law depends on farmers’ trust in its enforceability (Hong, Luo and Hu, Reference Hong, Luo and Hu2020, p. 7). Overall, these findings suggest that legal knowledge influences CFR to some extent, but this impact is conditioned by the village’s economic structure, farmers’ past experiences, and their trust in the RLCL. A critical point in previous research lies in its focus on surveying the legal knowledge of village leaders while not sufficiently investigating the legal knowledge of ordinary farmers. Village leaders cannot continue practices that are not supported by ordinary farmers. Therefore, this paper decided to focus on the relationship between ordinary farmers’ legal knowledge and their support for customary practices.

2.4. Research objectives

It is important not only to focus on ordinary farmers’ legal knowledge but also to pay attention to various dimensions of the law. There is limited understanding of the multi-dimensional nature of legal knowledge. The RLCL has multi-faceted characteristics. At the macro level, it defines land ownership, influencing land transfer, labour allocation, and rural-to-urban migration patterns (Zheng, Gu and Zhu, Reference Zheng, Gu and Zhu2020, p. 339). At the micro level, it details the rights and obligations associated with household contracting, land transfer, leasing, and subleasing. However, existing studies often evaluate villagers’ familiarity with this law as a whole, overlooking its multi-dimensionality.

This paper dissects the RLCL into five dimensions for examination, including provisions related to rural community elites, village committees, protection of the HRS’s tenure, prohibition of CFR, and legislative intent. In our survey, we measured whether respondents possessed legal knowledge about these five dimensions. It investigates whether there are differences in villagers’ familiarity with them. Then, this paper explores how these differences in legal knowledge influence attitudes towards customary practice. It will contribute to understanding CFR from a multi-dimensional perspective. This research aims to explain why some rural areas continue to practice CFR despite the enactment of the RCRL. By examining the multi-faceted nature of the RCRL, it will further investigate the discrepancies that arise during the conversion of legal provisions into practical legal knowledge.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Why X village was chosen as the case study site

Customary farmland reallocation is a grey area, making it difficult to observe directly. Although it was formally prohibited by the RLCL in 2002, some rural areas continue to practice it. Existing studies often rely on large-scale national or cross-regional surveys, which, despite their wide coverage, lack depth in assessing legal knowledge. Therefore, this paper focuses on a detailed analysis of a village in the North China Plain to explore the multi-dimensionality of legal knowledge.

A quantitative research method was adopted, selecting Village X in the central North China Plain for the survey. Village X is a typical agricultural area with a per capita farmland area of 0.16 ha, close to the per capita farmland area of Shandong Province, which is 0.08 ha (considering that about 60% of the population in Shandong Province does not own farmland due to their urban residency (Chengshi Hukou) but counting as the base).

Village X is a moderately sized village that retains the typical legacy of agricultural collectivization. According to the village committee, as of 2023, the village comprises 570 households with a total population of 2,242 individuals, averaging four people per household. These households are organized into ten production teams (Shengchan Dui), which serve as the basic units of the People’s Commune (Renmin Gongshe)—a structural remnant from the era of agricultural collectivization. These teams can be considered as sub-villages. The population size of each production team varies, with the largest comprising 380 individuals and the smallest just 98, averaging approximately 244 people per team.

The agricultural production in Village X primarily relies on two staple crops: wheat and corn. The village employs a rotational cropping system that achieves a “three harvests in two years” production model, meaning that three harvests are achieved over the course of two years. Winter wheat is sown in the fall of the previous year, harvested in the summer of the following year, followed by the planting of corn. After the autumn harvest of corn, winter wheat is planted again. Additionally, intercropping is a common agricultural practice. When winter wheat is harvested in the spring and the land is prepared for corn, farmers typically reserve a small portion of the land for vegetables, such as bell peppers, intercropped with corn. Although fruits like watermelon are rarely cultivated, they are not widespread due to their high maintenance costs. Through these diversified farming methods, Village X maximizes land resource utilization under the CFR.

The third characteristic of Village X is the prevalence of migrant labour, which reflects the unique phenomenon of migrant workers in China. Under China’s household registration system, many individuals registered as farmers seek manual labour in urban areas, and Village X is not an exception. According to the village committee, the population fully engaged in agriculture currently stands at 771 individuals. If we estimate roughly, about 60% of the 2,242 villagers constitute the workforce, excluding the elderly, children, and students. This suggests that approximately 50% to 60% of the labour force is in a mixed state, engaged partly in agriculture and partly in migrant work and referred to as the part-time farmer in this study. This phenomenon illustrates the fluidity of Village X residents between urban and rural settings and highlights that CFR is happening at the same time as urbanization.

3.2. The method of questionnaire survey

The survey was conducted in 2023, with 154 questionnaires collected. To ensure villagers spoke freely, we collaborated with coordinators who explained the survey’s purpose and clarified the questionnaire content. Survey respondents were collected using a combination of the following methods. The first was snowball sampling, whereby the first person to respond was asked to refer an acquaintance, who in turn referred the next person, and so on. The second method was to ask people who happened to meet while walking around the village to answer the questionnaire in order to correct the personal network bias caused by the first method. Because of these methods, it is not possible to calculate the effective response rate, but many villagers were willing to cooperate with the survey.

Depth and sensitivity are the primary considerations of this study. We conducted an in-depth measurement of villagers’ legal knowledge by breaking down the RLCL into five dimensions and assessing villagers’ knowledge of each. Additionally, CFR is a sensitive topic for villagers, who may be reluctant to answer or express their true thoughts. This study narrowed the survey scope and increased interaction with villagers. The survey was conducted with the assistance of coordinators to facilitate more accurate responses.

In addition to the questionnaire, we also conducted interviews. Therefore, in the following sections, we will incorporate analysis based on those results as well.

3.3. The characteristics of respondents

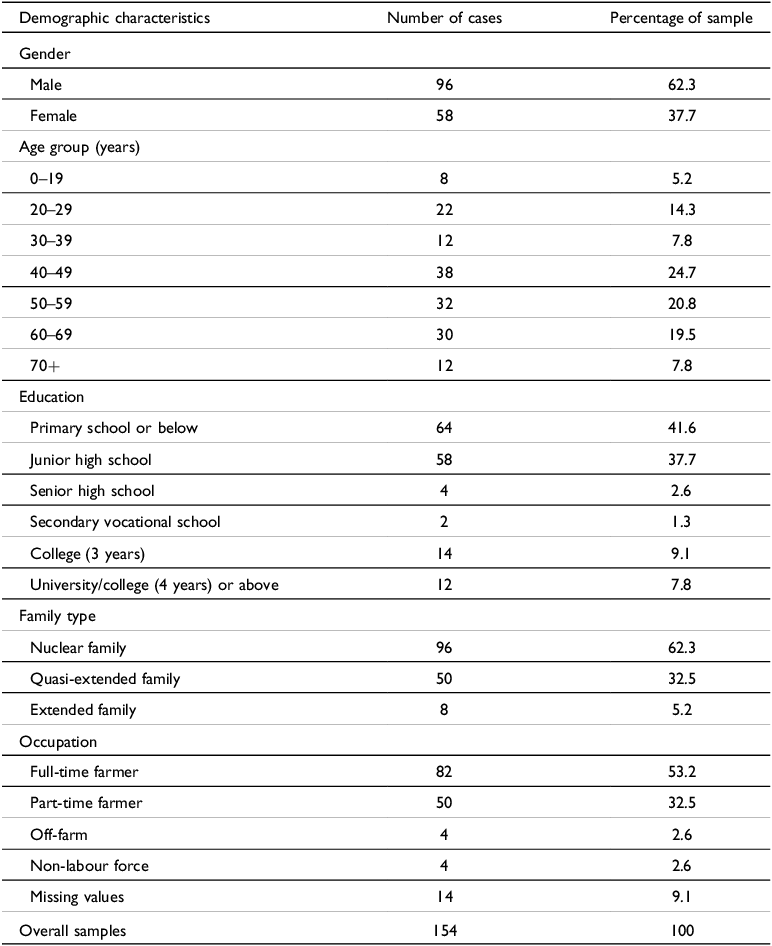

By analysing the basic characteristics of the respondents, trends in gender, age, educational background, and family type can be observed in Table 1. First, a total of 96 males and 58 females participated in the survey, with males constituting approximately 60% of the respondents. Although this proportion is slightly higher, it is reasonable considering that males in Village X are typically the main labour force among migrant workers. Second, 65% of the respondents are aged between 40 and 69, which is the primary age group involved in agricultural activities. Regarding educational background, over 75% of respondents have only received education up to junior high school or below, while about 15% have attained higher education.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents in Village X

A cross-analysis of age and education shows that those with education up to junior high school or below are mainly concentrated in the 40 to 69 age group, whereas higher education is more common among the 0 to 29 age group. This result aligns with the overall characteristics of China: the 40 to 69 age group attended school during the 1960s to 1970s when educational resources in China were scarce, so most did not receive adequate education. In contrast, the 0 to 29 age group attended school during the 1990s to 2000s, benefitting from the higher education expansion policy (Daxue Kuozhao Zhengce) in China, which allowed many young people to pursue higher education opportunities.

Regarding family type, over 95% of respondents come from nuclear or extended families. Cross-analysing family type with age reveals no significant distribution differences between nuclear and extended families, consistent with the definition of nuclear families that include only parents or parents with unmarried children living together. For instance, respondents might be unmarried and living alone, living with parents, living with a spouse, or living with a spouse and children, all of which are classified as nuclear families. This finding also aligns with research indicating that family units in northern China tend to be smaller, whereas those in southern China are larger (Peng, Reference Peng and He2022, pp. 81–111).

In terms of occupational distribution, about 50% of respondents are engaged in full-time farming, and 30% are involved in part-time farming. The high percentage of full-time farmers in the results is likely because those who leave for seasonal work are often absent from the village, making it difficult for them to be included as survey respondents.

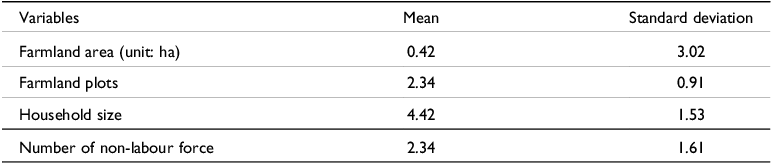

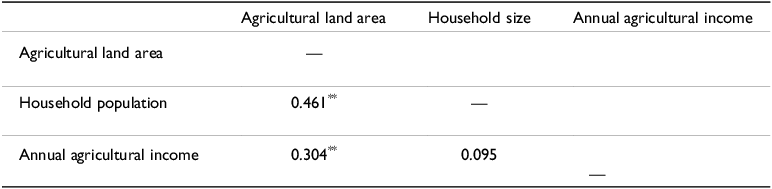

From the perspective of agriculture and income, the characteristics of the respondents reveal certain patterns. As shown in Table 2, firstly, the respondents, on average, own 0.42 ha of farmland. Given the average household size of four members, the average farmland per person is 0.105 ha. This figure is reasonable compared to the overall average per capita farmland area in Village X of 0.16 ha and the average per capita arable land area in Shandong Province of 0.08 ha. Additionally, each family has an average of two non-labour force, including young children, elderly members, or students, who do not participate in agricultural production.

Table 2. Agricultural characteristics of the respondents in Village X

It is noteworthy that the number of farmland plots is closely related to the characteristics of the CFR in Village X. The village’s farmland is divided into two regions, south and north, located on either side of the central road. The southern farmland has a reallocation cycle of ten years, while the northern has a cycle of five years. As a result, farmers typically have one plot of land in each of these regions. Survey data show an average of 2.34 farmland plots per household, reflecting this situation. The reason the average exceeds two is that there are many small agricultural roads within the southern and northern farmlands, causing some households to have their farmland divided into multiple plots in either region.

3.4. Theoretical hypotheses and methods of testing

This paper hypothesizes that farmers may continue to support the practice of farmland reallocation due to the limited knowledge of the law prohibiting it. In other words, farmers with accurate legal knowledge tend to exhibit lower levels of support for reallocation activities. Factors considered to be effective in influencing attitudes towards CFR include the benefits derived from CFR, the type of agriculture farmers wish to pursue, and land use practices. Therefore, after identifying the impact of these variables, it is necessary to examine whether legal knowledge independently affects attitudes towards reallocation when these variables are controlled. If it can be proven that legal knowledge influences attitudes towards CFR, it can be said that spreading legal knowledge in rural areas is a necessary policy for the future.

To test this hypothesis, this paper will first present how CFR is conducted based on survey results. Subsequently, we will describe the current state of farmers’ attitudes towards CFR and their legal knowledge. Finally, a regression analysis will be conducted to validate the hypothesis.

4. Results

4.1. How does the village reallocate farmlands?

To better understand the CFR in Village X, it is necessary to briefly outline its mechanism. As previously mentioned, the farmland in Village X is divided into two areas, south and north, along the central road of the village. These two areas have different reallocation cycles: the southern area has a ten-year cycle, while the northern area has a five-year cycle. Consequently, the reallocation in the northern area is referred to as “small reallocation,” while the reallocation involving both the southern and northern areas is called “large reallocation.”

Despite the differing reallocation cycles of the southern and northern areas, the eligibility and methods for participation in reallocation are consistent. All members registered in household registration systems as villagers of Village X, regardless of their labour capacity, are eligible to participate in reallocation. This means that working-age individuals, young children, and the elderly are all counted equally, and that farmland is reallocated in proportion to the number in each household. The CFR typically takes place after the Mid-Autumn Festival on the Chinese calendar (Zhongqiu Jie), following the corn harvest and before the winter wheat sowing. The process is completed by the village committee and respected villagers through confirming the village’s population and farmland, calculating the per capita farmland area, and dividing the farmland into several plots. Subsequently, a drawing ceremony is held to determine the location and allocation order of each household’s farmland. After the reallocation is completed, farmers plant winter wheat on their newly allocated land and maintain this layout for five or ten years.

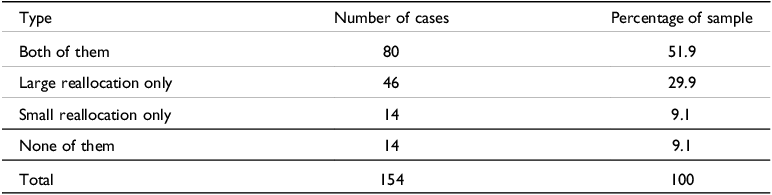

Village X adopts a principle of completely ignoring farmland quality. No matter whether the land is fertile or barren, near a river or on high ground, or close to or far from agricultural roads, it is all considered as the same type of farmland. Even if the farmland area is reduced due to graves, which is a local custom to set up graves on farmland, no compensations are made. In Table 3, our survey data indicate that 51.9% of respondents have experienced both large and small reallocation, 29.9% have only experienced large reallocation, 9.1% have only experienced small reallocation, and 9.1% have not experienced any reallocation.

Table 3. Respondents’ experiences with CFR

Looking specifically at age groups. CFR emerged with the establishment of the HRS. Although there are no specific CFR records for Village X, it can be inferred that it originated around 1995, as 95% of China’s villages had universal access to HRS in that year, which means at least two large round reallocations occurred. For the 40 to 69 age group, they have experienced both large and small reallocations. Newly established households may have participated in small reallocation, acquiring the use rights of the northern farmland, or may not yet have participated and relied on the farmland of the male partner’s parents.

Cross-analysis shows that those who have not participated in CFR or have only participated in small reallocation are primarily concentrated in the 0 to 29 age group, while those who have participated in both are mainly in the 40 to 69 age group. Some individuals in the 0 to 29 age group also reported participating in both, likely because they live with their parents and consider their parents’ experiences as their own. As long as the current situation persists, these new households will gradually evolve into households participating in both large and small reallocations.

In practice, farmland reallocation is conducted at the production team (Shengchan Dui) level rather than at the village level. However, due to the snowball sampling method employed in this study, the survey respondents were biased towards certain production teams. As a result, we were unable to investigate potential differences in customary practices or perceptions among the ten teams.

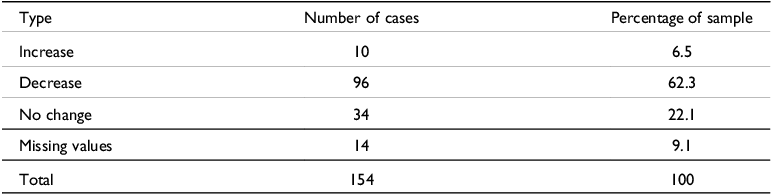

Next is the farmland area. Although maintaining the status quo allows new households to acquire farmland, the situation differs from a quantitative perspective. Data on farmland area changes following the most recent CFR in Table 4 indicate that 62.3% of respondents experienced a decrease in their farmland area, which is the highest proportion. Additionally, 22.1% of respondents reported no change in their farmland area, while only 6.5% experienced an increase.

Table 4. Changes in the land area of respondents since the last CFR

There are two primary reasons for the decline in household farmland area. First, a decrease in family members results in a reduction of farmland area. This decrease is typically due to natural changes such as deaths, marriages, and departures. Second, the population of Village X continues to increase, leading to a higher total population, which serves as the denominator in land reallocation calculations. As a result, the per capita farmland area for most households decreases.

To evaluate the actual effectiveness of farmland reallocation, we analysed the relationship between farmland area, household size, and agricultural income. The correlation analysis results in Table 5 indicate a significant positive correlation between household population and farmland area at the 1% confidence level, with a correlation coefficient of 0.46. In a partial correlation analysis that controlled for age group, income, and family type, the positive correlation between household population and farmland area remained significant at the 1% confidence level, with the correlation coefficient increasing to 0.55. This finding suggests that households with more members tend to possess more farmland.

Table 5. Correlation analysis among land area, household size, and annual agricultural income

NOTE: 1. N = 126. 2. Method: Spearman’s rho. 3.

** =p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Consistent with this result, farmland area and annual agricultural income also showed a positive correlation at the 1% confidence level, with a correlation coefficient of 0.34. This positive relationship persisted even when controlling for age group, household size, and family type, with the correlation coefficient rising to 0.37. The underlying logic is clear: as previously mentioned, the CFR in Village X applies to all residents registered as villagers under the household registration system. Therefore, larger households are reallocated more farmland during CFR, and larger farmland areas are generally associated with higher agricultural income.

It is important to note that since CFR is cyclical, changes in household size and farmland area are not adjusted in real time but instead exhibit a temporal lag, which may explain the correlation coefficient being around 0.5. Agricultural income is influenced not only by farmland area but also by factors such as land quality, weather conditions, and market prices, resulting in a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.4. These data support the hypothesis that the CFR in Village X effectively accommodates population changes for equitable land reallocation.

4.2. Attitudes towards customary farmland reallocation

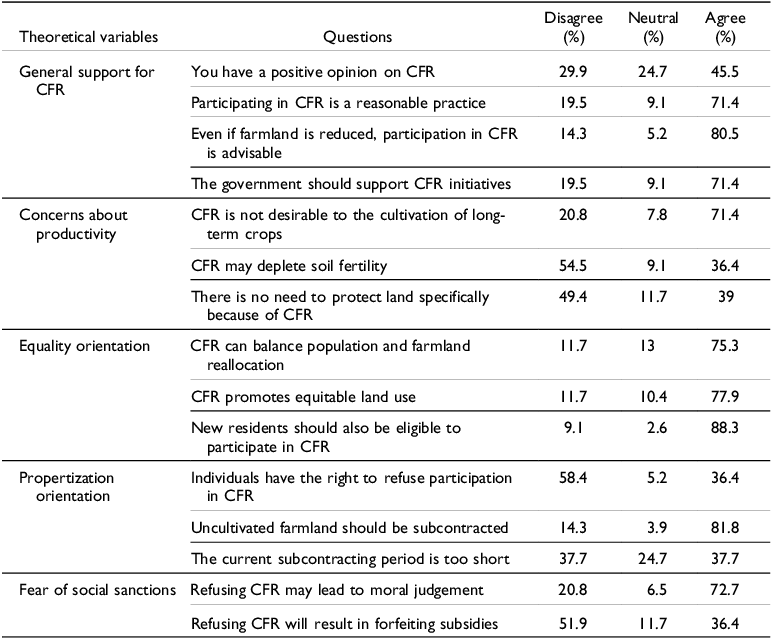

The following section presents respondents’ attitudes towards farmland reallocation practices based on the survey results. As summarized in Table 6, the survey collected respondents’ opinions in five main categories: (1) general support for CFR, (2) concerns about the productivity associated with CFR, (3) positive evaluation of the equality brought about by CFR, (4) the propertization orientation, which means farmland rights promoted by the RLCL, and (5) fear of social sanctions for not participating in CFR. Multiple questions were designed for each category to capture opinions from various perspectives.

Table 6. List of theoretical variables

NOTE: 1. N = 154.

Responses to the questions were measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). To provide a clearer understanding of the response trends, the results are simplified in Table 7 into three categories: “Agree,” “Neutral,” and “Disagree.”

Table 7. List of questions on legal knowledge

Regarding general support for CFR, there was more support than opposition for reallocation practices. Specifically, 71.4% of respondents agreed that CFR is a rational practice, and 80.5% believed that participation in these practices is necessary even if farmland is reduced after reallocation. As we will discuss later, the equity resulting from reallocation practices is highly valued among farmers. Additionally, 71.4% of respondents felt that the government should also support CFR. The response trends across these four questions showed a high degree of consistency, and reliability analysis confirmed that it was appropriate to combine them into a composite variable. Consequently, using principal component analysis, we developed a new theoretical variable called “General Support for CFR” based on these four questions. This new variable will be used in the regression analysis in later sections.

Regular farmland reallocation prevents farmers from continually using the same land, potentially hindering long-term farming practices and efforts to improve soil fertility. This situation may encourage opportunistic farming practices that deplete soil fertility for short-term gain. To assess concerns about agricultural productivity, three questions were designed. A majority (71.4%) of respondents agreed that reallocation is disadvantageous for long-term crops, such as fruit trees, suggesting that farmland reallocation is perceived as a barrier to long-term investment in farming. However, 54.5% opposed the idea that soil fertility could be depleted just before reallocation, indicating that most respondents do not believe this to be a significant issue. Similarly, there was near-majority opposition to the notion that soil fertility need not be a concern since the land would eventually be reallocated to others, implying that selfish and opportunistic behaviour may not be as prevalent as expected. In fact, in Village X, long-term fruit cultivation is rare, with single-year wheat crops being predominant. Interviews revealed no concerns regarding soil fertility in wheat. The distribution of opinions on the three questions about productivity concerns varied significantly. Reliability analysis showed that it was inappropriate to combine them into a single composite variable. Therefore, in subsequent regression analyses, we will use only the responses to the question regarding the disadvantages of long-term crop cultivation as a variable measuring productivity concern.

Regarding equality, this survey included three questions to assess respondents’ orientation towards equality in farmland reallocation. Respondents highly evaluated the benefits of reallocation for addressing population–land imbalances and promoting equal land use. Additionally, 88.3% agreed that newly independent households should be allocated farmland, indicating continued support in Village X for the idea that the village should periodically reclaim and reallocate farmland equitably according to the household size. The response patterns for these three questions were consistent, and the reliability analysis confirmed that it was appropriate to combine them into a composite variable. Therefore, a new variable, i.e. “equality orientation,” was created based on these responses.

The RLCL reduces the village’s collective ownership of farmland while enhancing the long-term protection of each household’s land use rights. It permits households to lease out the farmland that they are not utilizing and safeguards the lease rights of lessees as real property, a process referred to as propertization. Although the survey did not explicitly address the RLCL, it included three questions designed to gauge attitudes towards the propertization that the RLCL aims to promote. Legal knowledge of the RLCL was explored through a separate set of questions, which will be examined in the section 4.3.

Up to 81.8% of respondents agreed with the opinion that farmland should be leased out if children are not involved in farming. Responses were evenly split on whether the leasing period was too short, and opinions were also divided on the right to refuse farmland reallocation, with slightly more respondents opposing the idea. Despite these variations in response trends, reliability analysis indicated that it was reasonable to combine these three questions into a composite variable. As a result, a new composite variable called “propertization orientation” was created.

The next factor considered is the fear of social sanction. Two questions assessed the extent to which respondents feared social sanctions for refusing to participate in farmland reallocation. A significant 72.7% agreed that refusing participation could negatively affect interpersonal relationships, while concerns about negative impacts on subsidies were minimal. Therefore, it is inappropriate to combine these questions into a single measure. Thus, the question regarding the negative impact on interpersonal relationships will be used as the sole variable to measure fear of social sanctions.

The analysis above indicates that support for CFR practices remains strong, particularly due to the equity they promote. Simultaneously, many farmers expressed concerns about productivity, as long-term farming practices might be hindered, and fears of social sanctions for non-participation were evident. Next, we will analyse the extent of farmers’ legal knowledge regarding the RLCL.

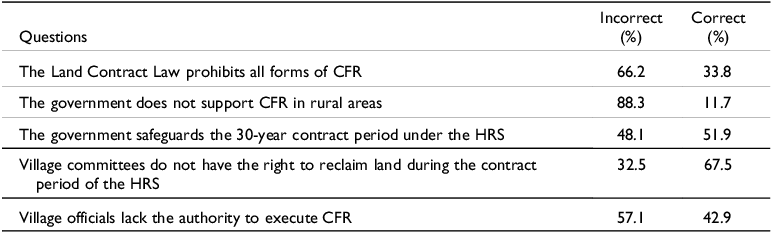

4.3. How to measure legal knowledge

The survey inquired whether farmers possessed accurate knowledge of various aspects of the RLCL. Based on the number of correct answers, a variable representing each respondent’s level of legal knowledge was created. This section explains how these measures were obtained and the extent to which farmers possess legal knowledge.

For knowledge of the RLCL, five questions, as shown in Table 7, were used to ask whether each statement was correct. The percentage of correct answers reflects the proportion of respondents who answered correctly, while the “Incorrect” rate includes both incorrect answers and responses of “Don’t know.”

As noted above, only 33.8% of farmers correctly identified that the RLCL prohibits reallocation practices. Considering the possibility of guessing correctly by chance, it is reasonable to conclude that most farmers in Village X are unaware of the prohibition of reallocation practices under the RLCL.

From Table 7, it is evident that the highest error rate concerns the notion that the state does not support CFR, with 88.3% of respondents disagreeing with this idea. This is naturally related to their level of legal knowledge. However, another possible explanation pertains to legal consciousness; the villagers do not believe their actions are wrong. They perceive their practices as just and thus think that the state and the law will ultimately endorse their perspective. Second, the error rate regarding the prohibition of CFR by the RLCL aligns with our expectations. Approximately 60–70% of respondents support CFR, which can be attributed to their lack of legal knowledge. The responses concerning the state’s support for HRS are split evenly, showing a fifty-fifty distribution.

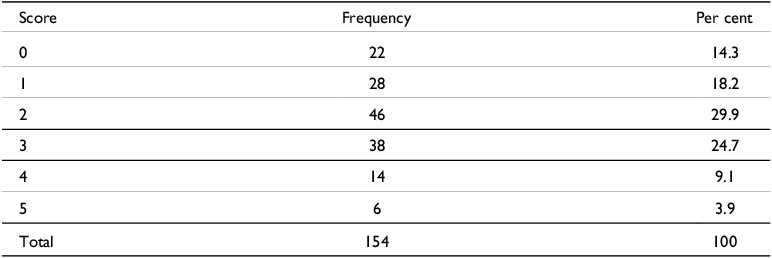

Next, the number of correct answers from the five questions in the previous table was calculated for each respondent, creating a variable representing the richness of legal knowledge based on the number of correct answers. In the following analysis, we will use this variable as an explanatory variable in hypothesis testing. The frequency distribution of the number of correct answers is shown in Table 8. The proportion of respondents who answered all questions correctly or four out of five correctly is low, indicating a generally limited level of legal knowledge among the respondents.

Table 8. Legal knowledge score (total)

NOTE: 1. N = 154.

Overall, about half of the villagers’ legal knowledge was accurate, with an average correct response rate of 41.6% across the five dimensions. By assigning 1 point for correct answers and 0 points for incorrect or uncertain answers, it was observed that 54.6% of respondents scored between 2 and 3 points, with an average score of 2.08 points.

4.4. The relationship between legal knowledge and customary farmland reallocation

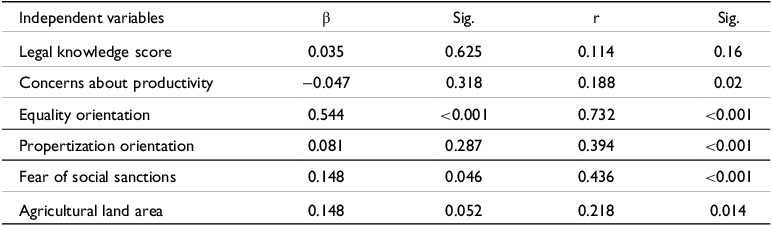

We will now proceed to test the hypothesis of this paper. The hypothesis to be tested is that farmers support the continuation of reallocation practices due to their limited legal knowledge and that those with greater legal knowledge are less supportive. To test this hypothesis, we will conduct a regression analysis to examine the impact of legal knowledge, as developed in section 4.3, along with other variables, to determine whether legal knowledge independently influences the tendency to support farmland reallocation practices, which are no longer legally recognized.

Moving to the hypothesis testing, Table 9 shows the variables influencing general support for farmland reallocation as determined by linear regression analysis. The variable “farmland area” is included as an explanatory variable, representing the extent of benefits received from reallocation practices, as more land area is gained through population-based reallocation. Contrary to the hypothesis, the analysis revealed that legal knowledge does not significantly influence support for reallocation practices. Additionally, variables such as productivity concerns and propertization orientation also showed no significant effect. However, there is a tendency for those with larger farmland areas, who benefit under the current system, to support reallocation practices, albeit at a significance level below 10%. The most influential factor is equality orientation; as we expected, stronger equality orientation correlates with greater support for reallocation practices. Fear of social sanctions also has an impact, with individuals who harbour stronger fears being more likely to express support for reallocation practices.

Table 9. MLR analysis with general support for CFR as the dependent variable

NOTE: 1. The Adjusted R 2: 0.382. 2. N = 154.

The results indicate that legal knowledge does not influence attitudes towards reallocation practices. The ongoing support for these practices is primarily driven by the strong endorsement of achieving equality through the regular reallocation of farmland according to household size.

One plausible reason legal knowledge did not affect attitudes towards these practices is that many farmers were unaware that the RLCL prohibits farmland reallocation practices, and there are too few farmers with accurate legal knowledge for this variable to have a significant impact.

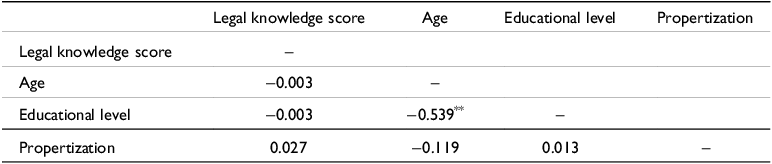

To investigate further, a correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between legal knowledge and variables likely related to it, as shown in Table 10. Typically, higher education, income, or age would correlate with more extensive legal knowledge. However, these variables were found to be uncorrelated with legal knowledge. This suggests that, despite the government banning farmland reallocation practices through legislation, this information has not been effectively communicated to Village X.

Table 10. Correlation analysis of legal knowledge, age, educational level, and propertization

NOTE: 1. N = 154. 2. Method: Spearman’s rho. 3.

** =p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Even if farmers lack accurate legal knowledge, those who inherently support the direction promoted by the law may still view the law favourably. Therefore, the correlation analysis shown in Table 10 also includes a variable representing support for the propertization of farmland, as advocated by the RLCL, to examine its relationship with legal knowledge. However, no correlation was found between the tendency to support propertization and legal knowledge.

5. Discussions

5.1. Key findings

First, let us summarize the key findings from the results. The hypothesis that the richness of legal knowledge influences attitudes towards CFR was not verified. In other words, we did not find a tendency for farmers with legal knowledge to oppose customs, or conversely, for farmers without legal knowledge to support customs due to ignorance. As outlined in the Results section, approximately 30% of respondents reported being aware of the legal prohibition against CFR. This paper proposes two potential explanations for this finding. First, based on the respondents’ age and educational backgrounds, it appears that legal knowledge has not been effectively disseminated, resulting in limited awareness of the prohibition. Second, there may be a deeper issue of disagreement with the law itself. The generally favourable attitude of villagers towards CFR suggests that, beyond a lack of legal knowledge, there may be a fundamental disconnect at the level of legal consciousness, with respondents not recognizing the legitimacy of the prohibition against CFR.

More than 20 years after the enactment of the RLCL, which prohibits farmland reallocation practices, this law holds little significance in Village X. Consequently, reallocation practices have continued as they were before the law was enacted. This suggests that in rural China, the state law is perceived as a distant entity, with customary practices being executed independently of it.

Despite the fact that many households experience a reduction in their farmland area due to reallocation, these practices are still supported by many farmers because of their high evaluation of the equality the CFR brings. It is intriguing to observe that, even today, the value of equality shaped during the People’s Commune (Renmin Gongshe) era is rated more highly than the value of productivity, despite the recognized negative impact on productivity due to the inability to engage in long-term cultivation investments.

However, some farmers participate in reallocation practices out of fear of social sanctions. If the government intensifies the enforcement of the RLCL and strengthens the prohibition of reallocation practices, farmers’ attitudes towards these customs may change in the future.

The observed lack of effective dissemination of the current RLCL provides a critical insight into the state of rural legal knowledge. On a deeper level, the analysis of trust and social sanctions offers a valuable perspective for examining farmers’ legal consciousness. These findings provide a window for future research into how rural residents reconcile formal legal frameworks with informal social norms.

5.2. Comparison with previous studies

The differences in villagers’ legal knowledge of the RLCL may stem from low educational levels, a lack of legal spread channels, and the absence of legal services in rural areas. This finding highlights widespread ignorance or misunderstanding of the law. Additionally, it suggests that the RLCL has not been effectively implemented in some rural areas, supporting Pia’s assertion that rural China is in a legal “vacuum” (Pia, Reference Pia2016, p. 287).

The fact that the legal knowledge does not significantly impact attitudes towards CFR may be due to the ineffective implementation of the RLCL in villages where CFR is prevalent. Although villagers may have encountered various sources of legal knowledge, both accurate and inaccurate, this knowledge has not effectively encouraged lawful behaviour. This result complements the studies by Deininger and Jin and Ren et al., which assumed that villagers correctly acknowledged legal knowledge and examined the relationship between the correct knowledge and CFR (Deininger and Jin, Reference Deininger and Jin2009, p. 36; Ren et al., Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2022, p. 338). This study, however, investigates whether villagers have correctly received legal knowledge and examines the relationship between this partial understanding and CFR. As a result, we found that the current situation is characterized by a lack of widespread legal knowledge among farmers, to the extent that we could accurately measure their legal knowledge. This was discovered because this paper surveyed ordinary farmers rather than village leaders, and this will likely serve as a new counterargument to Ren et al. (Reference Ren, Zhu, Heerink, Feng and van Ierland2022, p. 36) and Deininger and Jin (Reference Deininger and Jin2009, p. 338).

Regarding the emphasis on equality, we concur with Wang et al. (2011, p. 813) and Kong and Unger (2013, p. 18) that support for CFR is closely linked to its emphasis on egalitarian characteristics ). Policies prohibiting CFR may lead to an increase in income inequality within villages, a change that villagers may naturally dislike in the absence of external support. Therefore, external support such as welfare and employment opportunities are necessary to ensure that the gap between rich and poor does not widen significantly after the cessation of CFR, especially for those who are more dependent on farmland.

However, the study by Zhang and Kant (2002, p. 9) reminds us that an emphasis on equality is not always paramount. In their research on the reallocation of forest and arable land in southeastern China, they found that preferences for equality have limitations, particularly in cross-regional and cross-agricultural contexts. This study is limited to the North China Plain, an agricultural area where wheat is the primary crop, which may explain why farmers do not express significant concerns about production efficiency. This indicates that the priority given to equality may vary across different regions and agricultural types.

5.3. Limitations

This study’s limitations are also discussed here. First, while the analysis used legal knowledge as an explanatory variable, it was not effectively measured. It became apparent that many farmers lacked accurate legal knowledge, indicating the need for future analysis on how attitudes towards reallocation practices change once accurate legal knowledge is provided. This would involve examining which types of farmers may shift to opposing reallocation practices.

Second, this study was limited to a case study of Village X. Therefore, it was not able to identify the factors contributing to why reallocation practices have disappeared in some areas while persisting in Village X and other villages. This remains a topic for future research.

Third, the method of identifying respondents through snowball sampling may have introduced bias into the sample. For instance, it is necessary to analyse whether there are differences in support for reallocation practices or legal knowledge between village officials and non-officials. Given that village officials are likely aware of the RLCL, it raises questions as to why they do not communicate this law to other farmers, which should be addressed in future studies.

6. Conclusion

This paper empirically explores the relationship between villagers’ legal knowledge of the RLCL and their attitudes towards customary farmland reallocation. The results reveal that farmers’ legal knowledge is unreliable and that these partially correct understandings do not significantly influence their attitudes towards CFR. Additionally, we found Village X’s preference for equality. At the same time, we note that a portion of the villagers are concerned about the social sanctions when they try to reject the CFR.

Our conclusions prompt profound reflections. There is no doubt that China has made significant strides in the process of establishing the rule of law, as evidenced by economic development and the construction of the judicial system. However, the spread of legal knowledge in rural areas still warrants re-evaluation. As discussed in the literature review, many researchers have demonstrated the connection between legal accessibility and socio-economic development. This study does not intend to challenge these conclusions; rather, our findings indicate that in certain rural communities in China, the RLCL has not been comprehended by villagers as legal knowledge to the extent anticipated.

We propose two possible explanations for this observation: the inadequate dissemination of legal knowledge and a deeper issue rooted in the villagers’ legal consciousness. Due to the insufficient spread of legal knowledge, farmers continue to adhere to traditional practices, such as CFR. On the other hand, we found that villages highly value the principle of equality. Although, legally, the principle of equality inherent in CFR is considered illegal, from the villagers’ perspective, it is seen as a normal and just practice. At the level of legal consciousness, the principle of equality in CFR is perceived as legitimate.

Addressing the conflict between legal knowledge and consciousness may be crucial for resolving the CFR issue. As a policy recommendation, it is necessary to enhance public legal education and provide policy support to ensure that villagers not only understand legal provisions but also perceive them as just, thereby enabling the genuine spread of law in rural areas. Furthermore, legislators should reevaluate the justice of laws, integrate the legal consciousness of villagers, and embed this consciousness into national legislation. This fusion of legal knowledge and consciousness is necessary to effectively tackle the CFR issue.