In the 2010s, there was a marked rise in overtly populist electioneering and governing styles and approaches across otherwise differing democracies. From the United States (US) (Trump 1.0) and United Kingdom (UK) (the Brexit saga), to Central and Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, and others), India (Narendra Modi’s populist Hindu nationalism), Brazil, Turkey, and others, a distinctively direct form of politics now prevails in many places. This populist trend, further defined below, revolves around nostalgic appeals to a supposedly homogenous, authentic “true people” whose will has allegedly been frustrated by corrupt, out-of-touch elites. This new wave of populist leaders promised to give more direct expression to the “people’s will”, including bypassing constraints on that will in the form of constitutional or legal mechanisms. These liberal-democratic norms and institutions were framed as illegitimate because they (purportedly) inhibited the executive arm of government from protecting or advancing the people’s will. Elsewhere we have explored how this trend had a parallel at the supra-national level, with institutions and regimes of international law and global governance often framed as populist targets.Footnote 1 The rise of populism in democracies in the decade following the 2008–2009 global financial crisis amplified scepticism about the legitimacy and utility of international law, scapegoating its institutional architectures, and demonizing the idea of a globalization-enabling rules-based international order.Footnote 2 The pro-Brexit position in mid-2010s UK is perhaps the epitome of this: multilateral treaty-based bodies were portrayed at home as unaccountable foreign technocratic liberal and elitist entities, which were part of the pro-globalization establishment that was holding “the people” back from their “manifest destiny”.Footnote 3

When the list of 2010s populist democracies is recited, Rodrigo Duterte – President of the Philippines from 2016–2022 – is typically held up as an archetypal populist.Footnote 4 This article examines the Philippines under Duterte as a case study to deepen scholarly understanding of how populism at the national level shapes state engagement with (or disengagement from) supra-national institutions and regimes. The assumption in much of the “populism and international law” literature is that populist anti-institutional rhetoric and positions in domestic politics inevitably translate to corresponding changes in state policy towards supra-national institutions, thus driving disengagement from or de-legitimization of these entities.Footnote 5 While this remains a dominant framing, recent scholarship has called for a more nuanced approach. Rudolphy, for instance, has drawn on the Latin American experience to argue that populists’ relationships with international law are not necessarily uniformly antagonistic since they are often mediated by particular ideologies and shaped by contextual factors.Footnote 6 She argues, as we have also done elsewhere,Footnote 7 that the prevailing assumption of a negative relationship between populists and international law lacks robust empirical support, highlighting the need for a richer empirical grounding of these claims in particular political contexts.

In this article we draw on recent empirical fieldwork to interrogate the “populism = disengagement/de-legitimization” assumption as it relates to Duterte’s Philippines. This interrogation reveals a more complex and nuanced picture than is suggested by the binary of “pre-populist multilateral engagement” contrasted with “populist disengagement from international law and multilateralism”. We advance two interlinked arguments. First, we argue that the phenomenon of engagement by states with international law and institutions is more complex and varied than much of the international legal literature has hitherto acknowledged. Second, we argue that the translation of domestic democratic populist administrations’ priorities to international contexts is less straightforward and more variable than assumed. Here we highlight three themes that illustrate the complexity and variability of populist engagement with international law and institutions, namely: differentiating rhetoric from action; the instrumentality of populist engagement; and the filtering role of domestic institutions and bureaucracies in democratic societies.

This article proceeds in six parts. Part I offers a working definition of “populism” and, by reference to this, demonstrates how it is reasonable to characterize Duterte’s administration as falling within the disparate group of “populist” polities in the 2010s. Part II sets out our original conceptual framework of state engagement with international law and institutions.Footnote 8 Parts III, IV, and V then employ that framework to chart how the Philippines in fact conducted itself on the international stage during the Duterte presidency, in three areas governed in part at the multilateral level: human rights (and engagement with the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC)), international crimes (and engagement with the International Criminal Court (ICC)), and trade (and engagement with the World Trade Organization (WTO)).Footnote 9 Part VI then reflects on what the story of Filipino engagement in the Duterte era tells us about how varying levels of fortitude or resilience in domestic institutions can affect a populist executive’s often sceptical approach to international law and multilateral institutions, thus influencing the state’s multilateral engagement in fact.

I. Duterte as a “Populist” President

What do we mean by “populist” and in what ways might Duterte be so labelled? Much of the last decade’s literature conceives of “populism” as a divisive, non-inclusive or anti-pluralist, anti-establishment/anti-elite political style that seeks to restore a mythical golden age social ordering, in which “the people” (an often amorphous, virtuous, and neglected set of the voting public) are again sovereign and not subject to the self-interested national sabotage of local and/or transnational elites.Footnote 10 A combination of anti-elitism, on one hand, and a claimed popular sovereignty mandate from “the common people” abandoned by that elite, on the other, are central to the notion.Footnote 11 Similarly important is the presentation of policy options portrayed as hitherto marginalized by a self-interested or “too politically correct” elite.Footnote 12

The populist leader claims a popular mandate to address latent feelings of exclusion, disenfranchisement, and resentment among a group (the “forgotten and despised” majority) and is skilled in imbuing this group with a new sense of value, while articulating (in varying degrees of coherency) a platform of profound transformation.Footnote 13 A populist leader might promise to remove, as illegitimate and sometimes as foreign-imposed, various legal and institutional constraints, such as human rights, in order to fulfil this popular will.Footnote 14 On this basis, it is reasonable to frame Duterte’s presidency as “populist”. Indeed, a not insignificant volume of literature proceeds on that explicit basis.Footnote 15

Duterte’s presidency began on 30 June 2016 after a decisive national electoral victory. Duterte replaced President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III (2010–2016), who was from an influential political family and who had run on a platform of anti-corruption and good governance leveraging the legacy of his mother, President Corazon Aquino. Despite strides in improving the country’s economic standing and anti-corruption reputation, Noynoy’s presidency was widely criticized at home for its poor handling of disasters such as Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda (2013) and the failed Mamasapano counter-terrorism raid (2016).Footnote 16 Noynoy was seen as lacking empathy and being out of touch with the masses.Footnote 17 Duterte was elected in the context of this “ripe-for-change” political climate. Voters were also concerned about persistent crime, corruption, and economic inequality. Duterte’s election therefore reflected popular dissatisfaction not just with Noynoy’s governance but with the entire paradigm of post-1986 elite-dominated liberal democratic regimes.Footnote 18

Duterte’s six-year term (until 30 June 2022) was characterized by significant and often controversial and/or erratic policy shifts and governance styles. Duterte made headlines globally with his distinctive policies on crime, drugs, and foreign (especially US-China) relations. His campaigning and presidency were notable for his aggressive approach to crime, particularly his infamous “war on drugs” which led to thousands of deaths (many extrajudicial killings by law enforcement), drawing criticism from human rights groups and international bodies.Footnote 19 Yet many Filipinos supported his tough-on-crime approach, framed as a necessary measure to restore order and safety.Footnote 20 In foreign policy terms, Duterte sought to pivot the Philippines away from its traditional ally and colonial “parent”, the US, and towards China and Russia.Footnote 21 This shift was a significant departure from previous administrations and had implications for the country’s strategic positioning in the region. Among other things, Duterte trivialized the arbitral ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that the Philippines was able to obtain in its favour, against China, in terms of Chinese claims in the West Philippine Sea.Footnote 22

Duterte’s presidency had a very distinctive impact on the country’s political landscape. His leadership style, characterized by direct and often provocative rhetoric, and his willingness to challenge established norms and institutions, has left a lasting imprint on Philippine political culture, perhaps even creating a “rupture” in the trajectory of Philippine politics.Footnote 23 His approach and policies continue to influence the discourse and direction of national politics.Footnote 24 Scholars point, as hallmarks of “populism”, to Duterte’s efforts to portray himself as a tough but benevolent patriarch who best understands the country’s problems and cares personally for the people’s well-being and for the fulfilment of democracy’s true promise, in contrast (for instance) to unpatriotic and “obstructionist” human rights defenders.Footnote 25 From this stand-point, things such as “due process” or “human rights” or even routine governance and gradual reform are framed as a cunning elitist strategy (together with “detached and callous technocrats”) to subjugate the masses, or at least as impediments to solving societal problems such as poverty or crime.Footnote 26

Duterte’s governance style can be described as a form of illiberal or authoritarian (elected) populism.Footnote 27 From the outset it was marked by a paradox that seemed acceptable to voters: a strong law-and-order approach that nevertheless explicitly sought to bypass or ignore legal constraints, notably in the high-profile “war on drugs” policy. The thousands of extrajudicial killings (primarily targeting suspected drug users and dealers) attracted significant international condemnation not only for the scale and brutality and arbitrariness of these killings, but for Duterte’s personal and crude exhortations to law enforcement officers to kill with impunity.Footnote 28 This endorsement of extrajudicial actions undermined the rule of law and eroded the accountability mechanisms typically associated with democratic governance. Beyond the “war on drugs”, Duterte displayed authoritarian tendencies in his dealings with political opponents, activists, human rights defenders, and the media. High-profile cases, such as the imprisonment of Senator Leila de Lima,Footnote 29 a vocal critic of Duterte’s drug war, and the revocation of the franchise of ABS-CBN,Footnote 30 the country’s largest television network, underscored his administration’s readiness to use state power to silence dissent. Duterte also sought to consolidate power within the executive branch. He made frequent threats to declare martial law and took steps to centralize and concentrate authority, sometimes bypassing legislative processes and other checks and balances.Footnote 31

Duterte enjoyed political support from across economic classes, gender, and age groups.Footnote 32 He initially engaged with both left-wing and right-wing groups, and while his support from the left later evaporated, he remained popular with the general public.Footnote 33 Populist economic measures (the pushes on infrastructure, free tertiary tuition, and social welfare) were popular with his “base” and helped cement his image as a pro-poor president.Footnote 34

Duterte’s erratic policy shifts and unpredictable governance style can be understood through Mudde and Kaltwasser’s characterization of populism as a thin-centred ideology or one that lacks a fully developed ideological programme and which must therefore attach itself to more comprehensive (thicker) ideologies such as nationalism, authoritarianism, or socialism.Footnote 35 This conceptualization sheds light on the volatility and situational pragmatism that marked Duterte’s presidency. Lacking a discernible fixed ideological core, Duterte was able to pivot across disparate policy domains, such as promoting infrastructure spending and social welfare in one moment,Footnote 36 while embracing militarized responses to crime and centralizing executive power in another.Footnote 37 This ideological flexibility enabled an eclectic governance style that could accommodate both populist economic appeals and authoritarian law-and-order narratives, depending on political expediency. It also underscores the importance of situating Duterte’s political choices in context, rather than viewing them as purely strategic. In what follows, we introduce an analytical framework for evaluating how such political orientations may translate into varying modes of engagement with international institutions.

II. Introducing a framework to map, measure, and understand engagement by states in international institutions

International law and international relations scholarship require both more fully theorized and empirically grounded approaches to understand how the populist backlash at the national level impacts supra-national institutions and governance.Footnote 38 While the “populism and international law” literature tends to assume a negative effect of the former on the latter, there is a need for more empirically grounded country- and institution-level studies to help us understand the “underlying tendencies” behind the “foreground noise”.Footnote 39

This article’s main goal is to chart whether and in what ways Duterte’s populist invective manifested, in fact, in shifts in Manila’s multilateral engagement patterns in the three areas (human rights, international crime, and trade). Based on interviewee data, we plot such shifts against our original conceptual framework, developed more fully elsewhere,Footnote 40 charting modes of state engagement with international law and institutions in the context of domestic-level populism. This framework enables us to challenge the assumption that populism in the bloodstream of the body politic automatically transmits in an unfiltered way to international-level talk and action, prompting state disengagement from international regimes and institutions. As noted, the typology allows us to move beyond the binary of “pre-populist engagement” versus “populist disengagement” by adding more nuance to postures taken by states under populist leadership.

Our typological engagement framework comprises two spectrums of modes of behaviour, from proactive disengagement to proactive engagement, and from destructive to constructive action. We also separate rhetoric and action, since domestic-level populist rhetoric about an international organization may not necessarily be accompanied by any particular measures by that state towards the institution or treaty regime. The engagement typology offers greater precision and analytical utility in terms of the variety of forms or positions such behaviours might take, while enabling analysis of how these may shift over time even during a single administration in any state, or vary from one institution to another (same state) or one state to another (same institution). Four other interesting research areas are not reflected in this framework and explored elsewhere.Footnote 41 First, the study of what drives populism, including how supra-national governance arrangements feed into this. Second, through which mechanisms or vectors, and with what distortions, populism at the domestic level translates to a state’s multilateral level positions.Footnote 42 Third, there is a separate question – also not explored here – about the intended and actual effects, at different points in time, of shifts in a state’s engagement posture, on the legitimacy, efficacy (etc.) of an institution or regime. Fourth, such a framework can only plot observable postures adopted by a state: a much harder empirical question is whether different engagement modes or postures reflect coherent, considered, internalized principled positions or rather are merely game-playing expediencies as part of the tactics and strategies and to-and-fro’s of multilateralism; states may also simply lack the diplomatic or policy-making capacity or leverage to manifest any intended shift in position.

For the purposes of this article, we focus on engagement as observed in actions taken by the Philippines, and in Duterte’s rhetoric. We chart from proactive deliberate disengagement from the legal order, regime or institution(s) (withdrawal of all interaction) at one extreme, through passive disengagement to non-engagement, then to passive or formalistic engagement, and all the way across to proactive engagement. On the vertical (Y) axis, we plot a negative to positive spectrum from bottom (destructive or disruptive behaviours) up through obstructive ones, to supportive behaviours, to the top (constructive and facilitative behaviours). This vertical scale’s use of loaded terms “constructive” and “destructive” may suggest pre-commitment to certain values or assumptions, and/or a particular vision of the international regime (or legal order overall). It is important to acknowledge that engagement that is destructive of one institution may actually be creative of another, alongside or in its place, one that even on the same value-set of normative assumptions is more legitimate and effective. Yet for our present purposes, an engagement mode is “destructive” (at least in intent) if it aims to undermine the stated shared purpose of an institution or treaty arrangement.

When these two axes are combined, four quadrants emerge, on which the type and quality of a state’s engagement in any international institution can be plotted, at least provisionally for the purposes of debate and analysis. Figure 1 below sets out these quadrants, as well as some potential positions on the typology.Footnote 43 Here Committed Constructive Engagement (top right quadrant) is the ideal posture at least in terms of advancing the stated cooperation goals of the institution or regime. The least ideal is “destructive”, along the bottom half of the chart, whether by disengagement or by fulsome (but wrecking-ball) engagement.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Quadrants of Engagement.

The framework can be enhanced by plotting differential positions for the rhetoric of a state’s leaders and representatives (e.g. to a domestic audience) and its actual conduct at the multilateral level. Populist rhetorical attacks on an institution’s legitimacy or credibility may not necessarily be accompanied by any particular substantive measures to withdraw from, undermine, discredit or defund that institution. At the same time, it is possible that “mere” rhetoric unaccompanied by action is nevertheless intended to be, or is in fact, damaging to an institution or regime. This article’s goal is to tell the story of whether, and in what ways, one populist leader’s rhetoric (Duterte 2016–2022) resulted in shifting engagement by that leader’s state entity at the multilateral and foreign policy level, and which other actors and institutions had some agency in terms of whether “hot” rhetoric manifested at the supra-national level. The next three parts employ this engagement framework to analyze how Philippine engagement in international institutions differed across different issue areas. Part III examines engagement with the UNHRC, Part IV with the ICC, and Part V with the WTO.

III. Duterte and the UNHRC

Duterte displayed open contempt for human rights, perceiving them as incompatible with his war on drugs. In his first “State of the Nation” address, he declared that human rights must “work to uplift human dignity. But human rights cannot be used as a shield or an excuse to destroy the country”.Footnote 45 As Duterte framed it, human rights trivialized criminality and shielded criminals who, in his view, did not deserve protection. Throughout his presidency, he persistently criticized the international human rights system and its advocates. He directed expletives at United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur Agnes Callamard and warned her not to threaten him after she made known her observations about the drug war.Footnote 46 He used anti-rights rhetoric in public addresses to de-legitimize and scapegoat human rights advocates and church leaders, declaring of these critics that “Your concern is human rights, mine is human lives”.Footnote 47 He purported to direct that the funding of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), an independent government agency constitutionally created to perform check and balance functions on the use of government authority, be cut right back.

A. The Iceland resolution

Duterte’s disregard for (and active dismissal of) human rights attracted international attention. On 11 July 2019, the UNHRC adopted a resolution on the promotion and protection of human rights in the Philippines.Footnote 48 The resolution, sponsored by Iceland, expressed concern over allegations of human rights violations in the Philippines, particularly those involving extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and detention, as well as intimidation and persecution of human rights defenders and others. The resolution called for impartial investigations and asked the government to cooperate with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, such as on facilitating country visits. Eighteen UNHRC member countries voted in favour of the resolution, 14 were opposed, while 15 abstained.Footnote 49

Duterte criticized the resolution’s proponents in abusive terms and maintained that they did not understand the social, economic, political problems of the Philippines.Footnote 50 However, this overtly populist, anti-institutionalist approach did not result in the country’s withdrawal or disengagement from the UNHRC. In Geneva, the Philippines’ foreign service team was more circumspect and diplomatic, despite initial misgivings by foreign service officers about the resolution. In a “touch of diplomatic mastery”,Footnote 51 the Philippines successfully proposed a joint resolution with Iceland which created the UN Joint Programme. UNHRC Resolution 45/33 called for “Technical cooperation and capacity-building for the promotion and protection of human rights in the Philippines”.Footnote 52 The three-year programme called for capacity-building and technical cooperation in six key areas, namely, strengthening domestic investigation and accountability mechanisms; improved data gathering on alleged police violations; civic space and engagement with civil society and the CHR; strengthening the national mechanism for reporting and follow-up; counter-terrorism legislation; and human rights-based approaches to drug control and counter-terrorism.Footnote 53

Instead of resisting the directives in the resolution, the Philippine contingent at the UNHRC was able to change the messaging surrounding the resolution by cooperating and finding a way forward that did not involve disengagement from UN processes yet was tolerable to the President in his domestic political context. The then-Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Teodoro Locsin, Jr., stated that the UN Joint Programme “embodies the partnership, trust-building, and constructive engagement between the Philippines and the UN on human rights promotion and protection”.Footnote 54 For then-Secretary of Justice Menardo Guevarra, it was a manifestation of the “sincere efforts of the Philippine Government to infuse its law enforcement and investigative operations with a human rights dimension”.Footnote 55

B. Universal periodic review

The Philippines also continued to participate in the UNHRC’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR)Footnote 56 peer-evaluation process notwithstanding doubts expressed, early on, by the Duterte administration and initial moves by it to delay the scheduled UPR. Instead of disengaging from the UPR, participation by the Philippines during the Duterte administration was merely not as fulsome as in previous years. Certain sectors were excluded from the consultation process, such as the CHR. The CHR had historically participated in the state consultation process and in the preparation of the national report. As Duterte openly criticized the CHR for its position on the “war on drugs”, it was not included in government activities and functions, was ostensibly uninvited as well from consultations and in the preparation of the state report, and was, at one point, at the risk of being defunded.Footnote 57

Nevertheless, the Philippines was still able to participate in the UPR even if certain sectors lacked representation. Members of the diplomatic corps have asserted that this demonstrated a commitment to human rights.Footnote 58 In their view, statements of the President can be attributed to domestic politics, but the state’s commitment to human rights endures.Footnote 59 While there is a belief in some quarters that the political rise of Duterte reflected the country’s latent authoritarian culture or proclivity,Footnote 60 Presto and Curato found that even at the height of Duterte’s presidency, a majority of Philippine citizens maintained a belief in human rights and due process.Footnote 61 Public support of the drug war did not necessarily equate to acquiescence with the human rights violations conducted in its implementation.Footnote 62

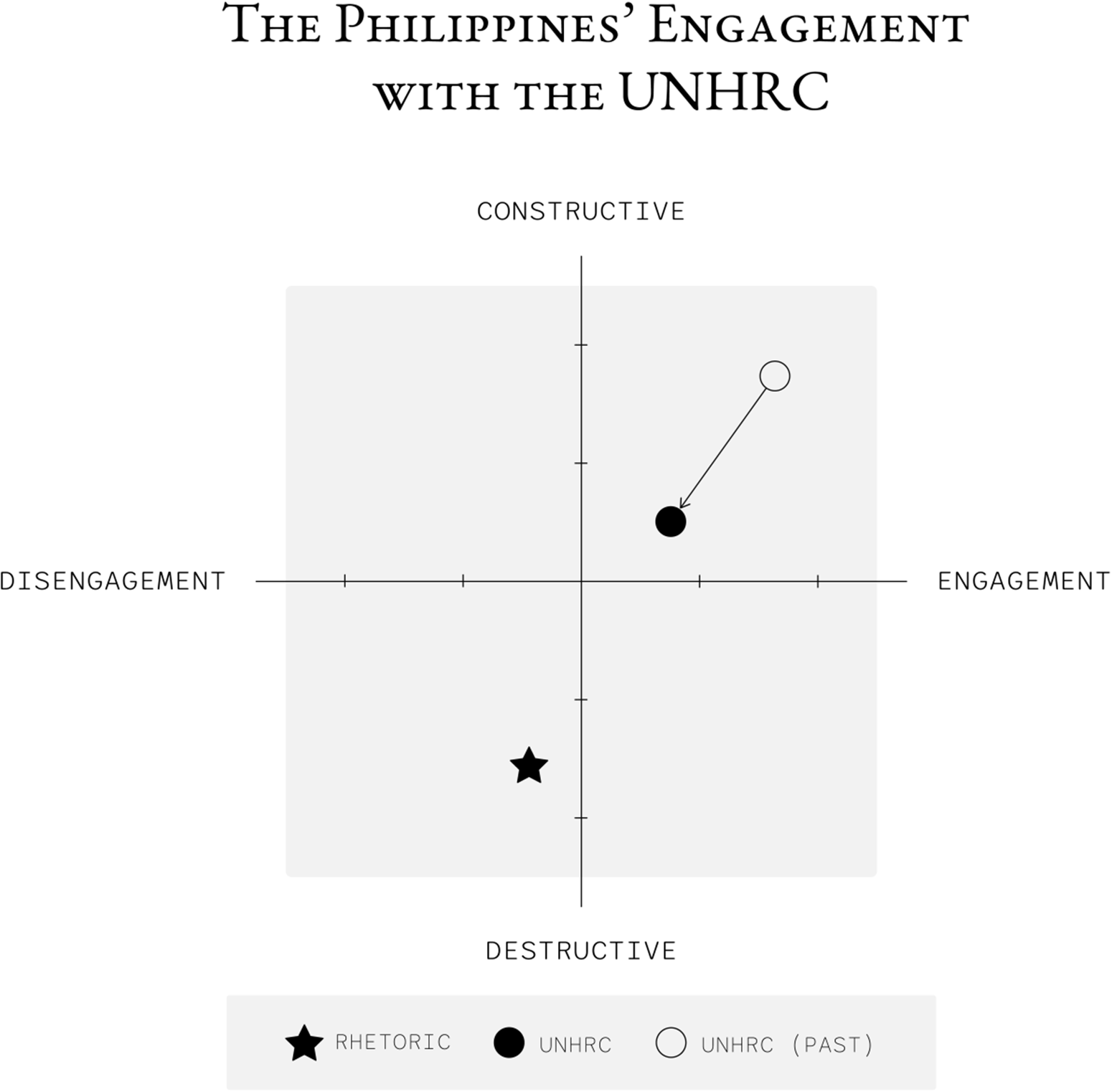

Using our typological framework, we can position the shifts in engagement of the Philippines with the UNHRC over time, as well as distinguishing between actual engagement and more inflammatory rhetoric (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Philippines’ Engagement with the UNHRC.

Thus, we see Duterte’s rhetoric, which was openly hostile to and critical of the institution and its processes, did not necessarily translate into disengagement. Arguably the rhetorical posture is best plotted as Defiant Non-Engagement: a state questioning the legitimacy of an international legal regime and not engaging with it, yet not going so far as to wholly undermine its legitimacy or block its operation. However, Manila’s position is better plotted, in action terms as opposed to rhetorical terms, as Ritualistic Engagement. Footnote 63 This is because, while within the administration there were criticisms of the UPR process and a lobby to disengage from it,Footnote 64 within the bureaucracy there was also a countervailing effort to continue engagement with the UNHRC. This continued level of engagement would be aptly described as ritualistic because it is relatively restrained as compared to previous engagements of the Philippines with the UNHRC.

This shift from Committed Engagement with the UNHRC under previous political leadership to Ritualistic Engagement during the Duterte administration was not consistent with the rhetoric of Duterte (which was far more suggestive of disengagement).Footnote 65 The marginalization of the CHR and non-governmental organizations from the UPR process exemplifies this decline in state engagement as well as the hesitancy of the government to cooperate with the investigation into the drug war.Footnote 66 With the completion of Duterte’s term of office, the Philippines began to move back towards Committed Engagement with the UNHRC both in rhetoric and action. President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., who succeeded Duterte in 2022, declared that he would continue to support all efforts of the country on the human rights agenda and has provided assurances to the UN resident coordinator in the Philippines.Footnote 67 The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, after a visit to the Philippines in early 2024, observed a “greater willingness” of the Philippines to cooperate on human rights procedures.Footnote 68 This complements the Philippines’ bid to become a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for the term 2027–2028.Footnote 69

IV. Disengagement from the ICC

While the Philippines maintained engagement with UNHRC processes despite its President’s hostility, the country’s stance toward the ICC was different. The Philippines became a signatory party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal CourtFootnote 70 in 2000, and the Senate ratified this in 2011. On 15 September 2021, the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber granted the ICC Prosecutor’s May 2021 application to commence an investigation of crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Duterte and top officials in the Philippines between 2011 and 2019 in the “war on drugs” campaign.Footnote 71 Duterte criticized the ICC, claiming that the court was infringing on Philippine sovereignty and that the examination was politically motivated.Footnote 72 On 17 March 2018, the Philippines filed a notification of its withdrawal from the treaty (which took effect one year later, on 17 March 2019).Footnote 73

On 16 May 2018, a group of Filipino senators questioned the withdrawal in the Supreme Court. Similar cases were filed by civil society actors and members of the legal profession.Footnote 74 The petitioners requested the court to instruct the executive to revoke its withdrawal. The case was decided by the Supreme Court almost three years later (March 2021). The Supreme Court dismissed the petitions on the basis that they were moot as the withdrawal had already been implemented.Footnote 75 The Court also declared that the withdrawal from the Rome Statute did not deprive Filipino citizens of an effective remedy for human rights violations and killings. According to the Court, a domestic law (the International Humanitarian Law Act) was available in the Philippines, which meant that mechanisms still existed within the national legal framework to prosecute and hold accountable those responsible for grave human rights abuses, including, potentially, Duterte and members of his administration.Footnote 76

Applying our conceptual framework, in respect of the ICC, presidential rhetoric and state action aligned. Manila’s position towards the ICC under Duterte can be characterized as Obstructive Disengagement (see Figure 3 below). Alternatively, it might be plotted as “destructive” in intent if not in effect: a state actively undermining the legitimacy and operations of the institution before withdrawing altogether. The Philippines’ withdrawal from the ICC was of course not destructive of the institution itself, but it was (so to speak) destructive of that state’s membership of it.Footnote 77 We can compare this position – rhetoric and action aligning but positioning changing over time – with our next example: the Philippines’ engagement with the WTO.

Figure 3. Philippines’ Engagement with the ICC and the WTO.

V. Duterte and the world trade system

In contrast to the Duterte administration’s turbulent relationship with human rights mechanisms and institutions, the approach of the administration to trade and international trade law and institutions is characterized as “stable”,Footnote 78 although the actual volume and direction of trade flows were affected by the regime’s pivot to China.Footnote 79

A. WTO

The Philippines is an original (1995) member of the WTO. Much of the Philippines’ early participation in the WTO centred around the necessary transition from a closed economy to a more open, liberalized trading nation.Footnote 80 The overarching interest for the Philippines in the trade space is in services, as this regulates the almost two million Filipinos who are overseas workers.Footnote 81 In addition to this, the Philippines has significant interests in agriculture and trade – particularly rice. The Philippines has initiated five cases in the WTO dispute system,Footnote 82 and been respondent to six more.Footnote 83 All five cases were initiated well before the Duterte administration (the most recent request for consultations were two 2002 cases against Australia, neither of which resulted in a panel).Footnote 84 There was however action in one case during the time of Duterte – an Article 21.5 Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) compliance application in the dispute with Thailand, which was brought five days before Duterte’s election on 4 May 2016. The case proceeded notwithstanding the change in Government, with the Philippines requesting a panel be formed in June 2016. Ultimately, the Philippines were successful in their claim, with a panel report handed down in 2018.Footnote 85

To use our framework of engagement, the Philippines’ activity at the WTO lies on the Committed Engagement side. Although not using the DSU at the rate or volume of larger economy states, the Philippines was nonetheless active and proactive in both using the DSU and seeking legal solutions for its trade issues. This is further reflected in the final stage of the case against Thailand. Thailand indicated its intention to appeal the panel report in 2019 in the context of a diminished but not yet fully dysfunctional Appellate Body (AB). Nonetheless, the three member AB indicated they would not be able to hear the appeal within the time limits given their severely constrained capacity, and in effect the case would have been appealed into the void. The Philippines kept pursuing its rights in light of Thailand’s non-compliance, taking a second recourse to Article 21.5 in 2018,Footnote 86 and requesting authorization to suspend trade concessions pursuant to Article 22.2 of the DSU in 2020.Footnote 87 The case then proceeded by facilitated negotiation, with both States signing an Understanding on Agreed Procedures Towards a Comprehensive Settlement of the Dispute in Thailand-Customs and Fiscal Measures on Cigarettes from the Philippines’ in 2022 which provides for the creation of a bilateral consultative mechanism to reach final settlement.Footnote 88

The Philippines’ approach has been consistent on this matter at least across three administrations. The Philippines more generally positions itself as a “friend of the [WTO] system”.Footnote 89 The Duterte administration overlapped with the period where the US started blocking reappointment of AB members, leading to its eventual disfunction.Footnote 90 During this period, the Philippines urged (unfruitfully) the US to fill the vacancies.Footnote 91 The Philippines maintained a strong diplomatic presence at the WTO throughout the Duterte’s presidency. The Duterte regime’s populist tendencies did not seem to impact engagement with the WTO in any meaningful way: the Philippines remained constructively engaged with the system throughout the period.

While like with the ICC, rhetoric and action aligned in respect of engagement with the WTO, unlike the ICC there was no movement in engagement. We can thus compare and contrast engagement with the ICC shifting over time (as in Part IV above), with the consistent engagement with the WTO throughout the Duterte administration.

B. Interaction between trade and human rights

While engagement with the WTO remained consistent, the Duterte administration’s rhetoric and action on human rights did impact its ability to negotiate free trade agreements. In particular, negotiations on a free trade agreement with the European Union (EU) were suspended in 2017 as a direct consequence of Duterte’s war on drugs and the regime’s human rights record.Footnote 92 The negotiations were only resumed in March 2024.Footnote 93 The ability of the Duterte regime to engage with the negotiations was directly impeded by its human rights activities.

The above Figure 3 illustrates the shifts in engagement of the Philippines with the WTO and the ICC over time.

Trade concessions also influenced domestic policy on human rights. Duterte campaigned on a platform to re-introduce the death penalty to the Philippines (it had been abolished in 2006).Footnote 94 He maintained this policy once elected, including using his 2020 State of the Nation address to call for the re-introduction of the death penalty.Footnote 95 However, this never occurred. Human rights advocates in the Philippines, including the CHR, opposed the re-introduction.Footnote 96 As the Philippines had ratified Optional Protocol 2 to the International Covenant of Civil and Political RightsFootnote 97 (ICCPR) in 2007, any re-introduction of the death penalty would violate those treaty obligations. The CHR publicly argued that adherence to Optional Protocol 2, once ratified, was permanent:

The Second Optional Protocol prohibits, absolutely and permanently, the imposition of the death penalty in the Philippines … Once ratified by a State, the obligations of the Second Optional Protocol are incapable of being retracted or altered by the State at any time in the future.Footnote 98

However, given the Duterte administration’s stated rejections of international law,Footnote 99 the utility of such an argument could be questioned. Indeed, it was actually the potential impact on the Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP +) tariff concessions provided to the Philippines by the EU that proved more persuasive.Footnote 100 Eight countries currently receive GSP + concessions. To be eligible, developing countries must ratify and abide by 27 international conventions,Footnote 101 including the ICCPR.Footnote 102 Adherence to the prescribed conventions is monitored by the European Commission (EC), with each GSP + country receiving a “scorecard” on compliance.Footnote 103 Human rights bodies were able to persuade the Duterte administration that reintroducing the death penalty – in violation of Optional Protocol II – would risk the Philippines receiving too low a score from the EC, and being assessed as ineligible to continue receiving GSP + tariff concessions. In particular, the impact on the Filipino tuna fishing industry was stressed:Footnote 104 the very “people” that Duterte purported to protect would be directly negatively impacted. Thus, a possible Destructive Non-engagement with the international human rights regime was prevented not because of human rights law per se, but because of the trade incentives associated with it.

VI. Variability in the translation of domestic populist priorities to international contexts

One picture that emerges from the Duterte period is the variability in the translation of domestic populist priorities to international contexts. While domestically, Duterte’s rhetoric and policies often centred on a strongman approach, emphasizing nationalism and a focus on “law and order”, his administration’s foreign policy reflected a more fluid, less straightforward, stance.Footnote 105 Our case study of the Duterte administration reveals three emerging themes: differentiating rhetoric from action; the instrumentality of populist engagement; and the filtering role of domestic institutions.

A. Rhetoric and action

The Philippine experience with the UNHRC highlights the difference between rhetoric and action. Duterte’s fiery speeches and harsh denunciations of the UN were often calibrated for domestic audiences. However, these rhetorical outbursts were not always matched by any substantive shifts in policy. The Philippines continued to engage with the UNHRC by voting, as it always has, in support of the international legal order and international cooperation. It maintained its long-standing membership in the UNHRC and even at the height of the reactions to the Iceland Resolution, it was quick to reassure that there would be no withdrawal from the UNHRC or the UPR process. Duterte’s anti-rights rhetoric, therefore, appears to be less a reflection of a deeply ingrained ideological opposition to human rights and more a calculated stratagem designed to deflect criticism and fortify his hold on domestic political power. In contrast, where international institutions enjoyed domestic approval (or put another way, there was no domestic political gain in disparaging international institutions), engagement and rhetoric remained in lockstep: as seen in our WTO example above. This further goes to our second observation: that of the instrumentality of engagement.

B. Instrumentality

The Duterte administration exemplifies an instrumental engagement with international institutions, guided predominantly by self-interest rather than any discernible or consistent ideology. Contrary to the assumption of disengagement within the “populism and international law” literature, Duterte’s overtly populist approach did not result in a uniformly hostile or sceptical approach across all areas of multilateralism. On one hand, the government actively participated in trade-related institutions such as the WTO, recognizing the critical role of international trade in sustaining key industries and protecting the livelihoods of millions of overseas Filipino workers. On the other hand, institutions perceived as challenging the administration’s domestic policies, such as the ICC and the UNHRC, faced either disengagement or antagonistic rhetoric. This pattern reveals a calculated instrumentalist approach: engagement with global institutions was pursued when it directly benefited national objectives, while institutions that threatened to constrain the administration’s agenda were dismissed or undermined.

This pragmatic approach to multilateralism is further illustrated by the administration’s continued engagement with institutions like the WTO and the World Health Organization (WHO), which aligned with national priorities and was seen to provide tangible benefit. As discussed earlier, the Philippines maintained active participation in the WTO to safeguard and promote its domestic industries. Similarly, the Philippines demonstrated consistent collaboration with the WHO throughout the Duterte administration, underscoring the instrumental value placed on international partnerships in addressing national priorities. This was particularly evident in its response to pressing public health challenges. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the government relied heavily on WHO guidance to craft its public health strategies, including vaccination rollout plans and public information campaigns.Footnote 106 The WHO’s technical expertise and access to the global vaccine distribution network, the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) Facility, were instrumental in securing vaccines for the Philippine population, particularly during the initial supply shortages.Footnote 107

Beyond the pandemic, the Duterte administration continued to work with the WHO to address endemic health issues, such as cancer and heart disease, by adopting international best practices for disease surveillance, treatment, and prevention. Key priorities of the Philippine Department of Health were policies implementing the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC),Footnote 108 the WHO International Health Regulations,Footnote 109 and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Palermo Protocol).Footnote 110

Given the Philippines’ prominent role as a global provider of healthcare workers, particularly nurses, the country has a vested interest in prioritizing and ensuring the protection and well-being of its healthcare workforce. The Philippines collaborated with the WHO to safeguard its healthcare workers through several key initiatives. In 2018, the Philippine government enacted the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Act,Footnote 111 mandating employers to adhere to occupational safety and health standards. This legislation requires employers to inform workers about workplace hazards, provide necessary facilities and personal protective equipment, and uphold workers’ rights to refuse unsafe work. The WHO commended this move, highlighting its alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 8.8, which aims to protect labour rights and promote safe working environments.Footnote 112

The WHO has consistently emphasized the importance of supporting healthcare workers in the Philippines, especially during health crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO provided detailed guidelines on the appropriate use of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) to protect healthcare workers from infection.Footnote 113 These guidelines informed protocols in Philippine hospitals which implemented tiered levels of PPE protection based on exposure risk.Footnote 114 In 2021, the WHO urged the Philippine government to ensure adequate support for health workers, including sufficient staffing and mental health resources, to maintain a resilient healthcare system amid the pandemic.Footnote 115

The Philippines’ sustained collaboration with the WHO demonstrates a pragmatic approach to leveraging international partnerships for both immediate and long-term health goals. This relationship highlights the strategic alignment of national priorities with global standards, enabling the country to address public health emergencies like COVID-19 while also tackling chronic health challenges and safeguarding healthcare workers. By integrating international best practices and frameworks into domestic policies, the Philippines not only strengthened its healthcare system but also reinforced its commitment to the broader goals of global health governance. These efforts underscore a broader narrative: even amid political shifts and domestic challenges, the Philippines maintained a clear recognition of the critical role international institutions play in advancing domestic public health. Duterte did not turn his populist rhetorical attacks on the infrastructures of global public health, one illustration of the need to bring more nuanced institution- and issue-specific empirical analysis to bear on assumptions that populism at home necessarily results in disengagement with global governance bodies abroad.

Another illustrative (though inferential) example of instrumentality can be drawn from the Philippines’ overseas labour economy. As a country with over 10 million citizens working abroad and sending remittances home,Footnote 116 the Philippines maintains numerous Bilateral Labor Agreements (BLAs) with destination countries, often developed in consultation with the International Labour Organization and through engagement in multilateral labour forums. While this study did not include direct fieldwork on BLAs, publicly available government statements and policy actions during the Duterte administration indicate no observable attempt to scale back these arrangements or to withdraw from relevant international labour commitments.Footnote 117 On the contrary, the administration consistently invoked the protection of overseas Filipino workers as a policy priority. This pattern further supports our observation that populist leadership in the Philippines did not (contrary to the assumption that “populism = disengagement”) in fact entail wholesale disengagement from international regimes, particularly when those regimes were seen to reinforce economic welfare or national interest objectives.

C. Institutional resilience

Another key observation arising from a study of Duterte’s presidency within the frame of the “populism and international law” literature – and of relevance to enriching that wider work – is the pivotal role of domestic institutions and their relative resilience or fortitude in the face of populist pressures, for example to disengage from multilateral processes and forums.Footnote 118 Carothers and Hartnett have explored how public institutions and departments have a role to play in curbing the political ambitions of elected leaders and constraining a backslide into illiberalism.Footnote 119 Bauer and Becker have likewise argued that contemporary state bureaucracies have “autonomous tendencies” and could be a counterpoint to populist ideologies.Footnote 120 The multilateral engagement story during the Duterte administration highlights the varying levels and cultures of autonomy within different parts of the bureaucracy, as well as the importance of institutional transmission vectors in translating domestic drivers (such as a populist de-legitimization of supra-national mechanisms) into shifts in the mode or tone of multilateral engagement. Domestic institutions have a filtering role in the way that they shape and channel the state’s domestic policy preferences, priorities, and constraints into its participation and behaviour in multilateral forums. This involves framing how domestic issues are articulated and pursued on the international stage, influencing the form of a country’s engagement in multilateralism. In the case of human rights, the Philippines diplomatic corps was crucial in maintaining engagement in the face of domestic events that seemed to portend withdrawal from the multilateral human rights system and that involved explicit presidential condemnation of aspects of the UN system. In this sense, the Duterte case may also be interpreted not simply as one of populist moderation, but as a reflection of the limits of presidential power. Despite Duterte’s rhetorical bravado, the entrenched culture and professional ethos within the foreign service served as a brake on more radical shifts in international posture.

Even under a populist presidency, specifically one that openly disparaged human rights, the Philippine foreign service was ostensibly able to carry out its mandate of preserving international relations and remaining committed to the international legal order. This can be attributed to institutional fortitude and resilience within relevant parts of the bureaucracy responsible for this policy area, and the wider human rights ecosystem in the country. Interviews with retired and current foreign service personnel reveal a palpable sense of a proud tradition of adhering to a rules-based legal order. The same personnel who made an effort to mitigate Duterte’s inclinations expressed disagreement, under interview, with Trump’s acts of disengagement with international institutions. That disagreement appeared to be based on the principle of commitment to multilateral cooperation and engagement as important in itself.

The ability of Manila’s diplomats in Geneva to find a constructive approach to the domestic human rights critique reflected this long-standing commitment. According to Albert Del Rosario, a former Secretary of Foreign Affairs, the Philippines’ foreign policy is “firmly anchored on the principles of democracy, human rights, good governance and the rule of law”.Footnote 121 The Philippines has always been active in foreign diplomacy. Along with India and China, the Philippines was one of the first three Asian members of the UN. At times, the Philippines embraced a role of representative for less-developed nations. For instance, it fought for the inclusion of the words “self-government” and “independence” to be included in Article 76 of the UN Charter, on the objectives of the trusteeship system, a controversial move at a time when many countries were still under colonial rule.Footnote 122

The Philippines likewise adopted a leadership role in international human rights diplomacy. Since 1946, it had been a nearly continuous member of the Commission on Human Rights and the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, consistently reaffirming its commitment to promoting respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.Footnote 123 It was one of the 18 members of the Economic and Social Council that worked on the International Bill of Rights, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,Footnote 124 the ICCPR, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.Footnote 125 Following the establishment of the UNHRC, the Philippines was elected as one of its founding members.Footnote 126 The Philippines had consistently held a seat in the 47-member body, with the last term ending in 2021.Footnote 127 In the Philippines, the determination of the diplomatic corps to engage with international human rights processes and preserve its relations with the UNHRC constituted a source of institutional resilience that worked to constrain Duterte’s anti-human rights directives.

Reflection on bilateral security relations during the Duterte era also illustrates the role of national institutional fortitude in shaping foreign policy under populist leadership. Duterte’s presidency marked a significant shift in the Philippines’ approach to peace and security, particularly in the South China Sea. The maritime dispute dates back to 1995 when Chinese-built structures were discovered on Mischief Reef within the Philippines exclusive economic zone.Footnote 128 President Fidel Ramos, and his successors Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, aligned national policy with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the SeaFootnote 129 (UNCLOS), with Macapagal-Arroyo adjusting the Philippines’ baselines to conform to UNCLOS.Footnote 130

Duterte’s predecessor Noynoy Aquino elevated the dispute to the PCA under UNCLOS. This move sought to invalidate China’s “nine-dash line” claim and assert the Philippines’ sovereign rights over key maritime areas.Footnote 131 In 2016, the tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines, striking down China’s claims in the South China Sea. However, Duterte downplayed the significance of the arbitral decision, at one point dismissing it as nothing more than a “piece of paper”Footnote 132 and favouring bilateral negotiations with China. This shift reflected a more pragmatic approach to foreign policy, prioritizing immediate political and economic considerations over the long-term value of international legal mechanisms.Footnote 133 Duterte’s pivot to China also involved sharp criticism of the Philippines’ traditional ally, the US, citing grievances over historical injustices and US criticism of his human rights record.

Despite Duterte’s rhetoric, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) had sufficient institutional autonomy and fortitude that has largely resisted these shifts. The AFP, through the Philippine Navy, actively enforced maritime law in contested areas, conducting naval patrols within its exclusive economic zone and asserting freedom of navigation under international law.Footnote 134 These actions underscored the Philippines’ role in promoting freedom of navigation in a region increasingly militarized by China’s presence. Notwithstanding Duterte’s diplomatic overtures to Beijing, the Navy maintained close defence cooperation with the US and regional allies, conducting joint military exercises that reaffirmed the Philippines’ commitment to international security frameworks.Footnote 135

In domestic matters, the AFP also showed relative autonomy and corresponding restraint. While the Philippine National Police (PNP) took centre stage in carrying out Duterte’s anti-narcotics campaign, the AFP largely refrained from active participation, maintaining its focus on national security and defence.Footnote 136 This was a deliberate choice grounded in the military’s commitment to the rule of law, its constitutional role, and the preservation of democratic institutions. The military’s reluctance to be involved in Duterte’s drug war was not just indicative of its members’ belief that the campaign did not fall within its primary mandate; it was also a function of the military’s relative independence and autonomy regardless of populist pressure. Combined with the AFP’s international activities as outlined above, the AFP played a key role in counter-balancing Duterte’s overt bilateralist foreign policy and preventing the Philippines from veering too far from its traditional security partners or commitments to regional security frameworks.

VII. Conclusion

The varying patterns revealed by analysis of the Duterte administration’s engagement with international law and institutions illustrate the need for empirical work to move in a nuanced, fact-based way beyond the binary, in the literature, of pre-populist engagement versus. populist disengagement. Instead of a full-scale and across-the-board withdrawal from the international system, the Philippines under Duterte exhibited a range of behaviours, from Constructive Engagement with the WTO and WHO to Destructive Disengagement from the ICC. Domestic populist rhetoric and policies did not necessarily dictate state action on the international stage in any uniform or predictable manner. Instead, the translation of populist priorities into foreign policy and international legal positions was mediated by instrumentality and filtered by the interventions of bureaucratic actors.

What emerges is the role of relative institutional fortitude in mitigating the disruptive or isolationist impulses of populist leadership. Whether in the form of the diplomatic corps’ efforts to maintain engagement with the UNHRC or the AFP’s adherence to established relationships, these institutions acted as stabilizing forces in terms of the long-term policy trajectories of the modern Philippine state. Such resilience underscores the importance of autonomous structures in safeguarding multilateral commitments, even in the face of political rhetoric that challenges their legitimacy. In other settings, the anti-elite/anti-establishment refrain associated with definitions of populism might have meant that officials playing this moderating or filtering role could become targets of populist attack. However, this was not the case for the Philippine diplomatic service even in the most contested issue-area (human rights).

The Philippine experience offers broader lessons for international law scholars and practitioners grappling with the rise of populism within democracies. It highlights the importance of distinguishing rhetoric from action, understanding the often instrumental value of multilateral engagement for populist regimes, and appreciating the capacity of domestic institutions to act as buffers against the more illiberal tendencies of such governments. As populism continues to shape the global political landscape, these insights provide a critical lens for examining how those representing states in multilateral settings navigate the tension between political imperatives at the national level and their commitment to engaging with multilateral norms, regimes, and institutions at the international level.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive comments.

Funding statement

This research was supported by funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project grant DP220101584. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Research Council.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Nina ARANETA-ALANA is an Australian Research Council Postdoctoral Fellow at the College of Law, Governance and Policy, Australian National University.

Jeremy FARRALL is Professor at the College of Law, Governance and Policy, Australian National University, and Adjunct Professor at the University of Tasmania Faculty of Law.

Jolyon FORD is Professor at the College of Law, Governance and Policy, Australian National University.

Imogen SAUNDERS is Associate Professor at the College of Law, Governance and Policy, Australian National University.