Introduction

Sports mega-events, such as the Olympics, are now viewed as universal cultural spectacles and multidimensional promotional platforms (Dubinsky Reference Dubinsky2023). Owing to their influence not just on sport but the wider sociocultural landscape, they are considered “living heritage” on a global scale (Gold and Gold Reference Gold, Gold and Boulting2012; Pinson Reference Pinson2017; Ramshaw Reference Ramshaw2010). The Olympics, specifically, are advertised as “the world’s only truly global and multi-sport” event (https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games) as they not only promote the globalization of sports rooted in specific regions and sociocultural contexts but also showcase the culture and arts of the host country to the world through ceremonies and exhibitions, among which the opening ceremony is of particular importance. However, while scholarly attention has predominantly focused on outstanding cases of Olympic events, a new research agenda is emerging. This agenda seeks to explore the opening and closing ceremonies not just as staged displays of national identity but also as platforms for experimenting with complex cultural issues, involving contradictory narratives and engaging creative technologies. We consider the two Olympic games under study here as cases of relational creativity; the Nagano opening ceremony staged a fusion of local religious traditions and Western influences, in contrast, the Rio closing ceremony experimented with meanings of urban cosmopolitanism and cultural and social inclusivity.

Despite the growing importance of the opening and closing ceremonies, Lee (Reference Lee2021) points out that the number of studies on this subject is limited compared with studies that pursue the strategies and mechanisms of Olympic and sport diplomacy. The majority of academic research in this field explores the more outstanding or exemplary cases of Olympic events (mostly Summer Olympics), examining primarily to what extent these ceremonial presentations express the host nation’s culture and identity or implied nationalism (Bryant Reference Bryant2015; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Colapinto and Luo2012; Li Reference Li2014; Oettler Reference Oettler2015; Thomas and Antony Reference Thomas and Antony2015).

There is an emerging research agenda that not only considers these events as platforms for broadcasting a coherent culture and identity but argues that these platforms also engage with contradictory and more complex cultural issues. For example, starting from the 2000 Sydney Olympics, opening ceremonies have incorporated “interpretive cultural performances,” exploring intricate issues surrounding national sovereignty and cultural identity (Ellis Reference Ellis2012; Hogan Reference Hogan2003). These performances have delved into historical narratives, addressing the dichotomies between settlers and invaders, local and national, and culturally specific and universal (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Colapinto and Luo2012; Lee and Yoon Reference Lee and Yoon2017). Moreover, advancements in technology have further elevated these ceremonies, incorporating elements of virtual and augmented reality, as evidenced by the innovative presentations in the Beijing and London Olympics (Spencer 2008).Footnote 1

This article is situated within this emerging agenda that points to the more contested and ambiguous role in the making of meaning at opening and closing ceremonies not just as platforms for presenting a well-choreographed national image but also as sites for transition and experimentation with new meanings (Arning Reference Arning2013; Lee and Yoon Reference Lee and Yoon2017; Morgner Reference Morgner2022). Specifically, we raise the following questions: (1) how can this more experimental approach to meaning-making be conceptualized as a form of relational creativity? (2) What is the role of creative technologies and artistic formats as other agents of relational creativity? (3) How does this relational making of meanings emerge within the context of opening and closing ceremonies?Footnote 2

Relational creativity as sense-making: Olympic opening and closing ceremonies

The prevailing academic perspective characterizes Olympic Games as meticulously orchestrated global media spectacles transmitted worldwide (Bryant Reference Bryant2015; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Colapinto and Luo2012; Li Reference Li2014; Oettler Reference Oettler2015; Thomas and Antony Reference Thomas and Antony2015). These interpretations often presume a unidirectional flow of meaning from sender to receiver, such as from the media to an anonymous audience, who are expected to decipher these encoded messages. However, in this article, we seek to explore the process of meaning-making during the Olympic opening and closing ceremonies through the lens of relational creativity. Our motivation for adopting this approach stems from two primary reasons.

“Sensemaking is never solitary because what a person does internally is contingent on others” Weick (Reference Weick1995: 40). Relational or working together with others does not simply mean sharing meanings but considers to what extent sense-making creates workable relations, to what extent is it linking up actions and ideas (see Morgner et al., Reference Morgner, Hu, Ikeda and Selg2022). Expanding on George Herbert Mead’s concept of social meaning, we assert that sense-making, or what Mead terms as meaning, emerges and evolves through successive behaviors or sequences of actions. He describes a multifaceted “relationship [that] constitutes the matrix within which meaning arises, or which develops into the field of meaning” (Mead Reference Mead2015: 76). We contend that the act of making meaning must be viewed as a form of relational creativity, as it involves adaptive and subsequent responses, transcending mere transmission to become a creative process.

The notion of making meaning as relational creativity implies an opening up of new meanings, allowing room for experimentation with novel ideas with a relational context (Morgner and Aldreabi Reference Morgner and Aldreabi2020; Morgner and Molina Reference Morgner and Molina2019). It is in this relational context, which offers a space for creative exploration, enabling a contemplation of “what-ifs.” As noted by Coates and Coates (this issue), relational creativity refers to a relational mode of expression that works within and transcends existing contexts in an environment of interpersonal relationships. Relational creativity needs to consider an inward orientation, e.g., the collaboration with other people but also needs to consider an outward orientation, sometimes called commercial creativity (MacRury Reference MacRury, Hardy, Powell and MacRury2018). In the realm of meaning-making, collaborative experimentation, especially in managing contradictions and misunderstandings, becomes a form of relational creativity in itself (see Cattani et al. Reference Cattani, Ferriani, Colucci, Jones, Lazersen and Sapsed2013; Leach and Stevens Reference Leach and Stevens2020). Relational creativity thus manifests in the collaborative production of meaning and is also inherent in the resulting products of this creative endeavor.

Relational creativity embodies a dual structure in the context of meaning-making; it involves the creation of meaning through collaboration with others, and the resulting meanings can adopt relational forms, incorporating contradictions, comparisons, or negotiated interpretations in regard to the commercial context in which they are embedded. Consequently, relational creativity is not only a process of production but also permeates the products born from this creative endeavor.

Adopting the framework of twofold relational creativity, this study aims to better understand Olympic ceremonies in general and in Japan by exploring how the opening and closing ceremonies employ innovative aesthetic formats to guide and facilitate meaning-making. In addition, we investigate how relational creativity serves as a framework for testing new ideas and meanings, providing a fertile ground for creative experimentation and expression, but also how it is embedded in consumer demands, for instance, aimed at enhancing the host nation’s image, attracting tourism, and encouraging foreign investment. On the basis of this framework, we are able to understand how the structural conditions of relational creativity—e.g., how creatives coordinate, project, and innovate, as well as limit and constrain their work—mediate and translate into outcomes that may further advance innovations or constrain them. This framework enables us to overcome existing limitations in the field, which typically considers structural conditions within a social science paradigm and outputs within a humanities context. We believe this framework, with its focus on meaning-making, has excellent potential for testing in the context of Japan, where many cultural values emphasize the importance of symbolism and meaning, and group activities such as circles (sākuru), clubs (kurabu), or associations (kai) play a key role (see Morris-Suzuki Reference Morris-Suzuki1995, Sugimoto Reference Sugimoto2020, Coates and Coates).

Methodology: case selection and analysis

In the preceding sections, a myriad of research has explored the representation of the “nation” and “country” in the narratives of Olympic opening and closing ceremonies (Bryant Reference Bryant2015; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Colapinto and Luo2012; Li Reference Li2014; Oettler Reference Oettler2015; Thomas and Antony Reference Thomas and Antony2015). However, the crucial interplay of relational creativity in amalgamating with fresh aesthetic forms and media technologies to construct new meanings has been overlooked. To analyze these facets of relational creativity within Olympic ceremonies, our study focuses on Japan, a nation that has hosted four Olympic Games. Despite Japan’s significant role, with only the USA and France having hosted more Games, scant attention has been paid to Japan’s contribution to Olympic Games organization, particularly regarding Japan-led opening and closing ceremonies. Previous research predominantly fixated on the 1964 and 2021 Olympic Games in Japan, emphasizing a strong national identity, harmony, and hierarchical structures (see Tamaki Reference Tamaki2019). For instance, the mega-events of the Olympic Games in 1964 focused on a “public display of national achievements and virtues” in the aftermath of World War II (Horne and Manzenreiter Reference Horne and Manzenreiter2004: 193). Similarly, the 2021 Games primarily served nation-branding purposes, projecting an image of Japan characterized by “clarity, consistency, and simplicity” (Rookwood and Adeosun Reference Rookwood and Adeosun2021: 11–12).

Our focus pivots toward the periphery of these games, where relational creativity has greater potential to experiment with novel social concepts. A prime example is the handover (closing) ceremony of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, representing relational creativity in the process of meaning-making. This heightened potential for embracing relational creativity is rooted in Japan’s social uncertainty during this period. The theme of the Tokyo Games evolved from recovery and reconstruction post the March 2011 tsunami and nuclear disaster originating at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant to symbolize humanity’s triumph over the pandemic (Dubinsky Reference Dubinsky2023). Amid this backdrop, Japan faced various challenges, including scandals related to stadium construction, event logo design, and official documentary filming. Political and major advertising company pressure compelled a sudden alteration of the planned opening ceremony in October 2019, causing significant deviations from the original plans for the 2020 and 2021 ceremonies. This “lost idea” of the 2020/2021 Olympics finds expression in the flagship handover of the 2016 Rio Olympics closing ceremony. This was conceptualized and implemented by the production team involved in the original proposal and was an attempt by the younger generation of Japanese creators to experiment with the legacy of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which was the concept behind the country’s bid to become the host. In sum, the handover (closing) ceremony as part of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games operated within a context of social uncertainty that required a much more collaborative approach in the making of meaning, which is why we shift the focus from a more orchestrated notion to that of relational creativity.

The flag handover in Rio can be viewed not only as the inauguration of the “new Olympic era,” experimenting with fresh social ideas (Dubinsky Reference Dubinsky2019) but also as a precursor to the hybrid human–digital artistic expression that gained momentum in the 2000s. To explore the role of media technologies in contributing to relational creativity and transitioning to innovative artistic expressions (Tzanelli Reference Tzanelli2014), we briefly examine the opening ceremony of the 1998 Olympic Winter Games in Nagano. The turn of the millennium marked a significant period for Japan in hosting the Olympics, not only owing to the country’s evolving global economic role but also because of the introduction of diverse media technologies (Tajima Reference Tajima2004). For instance, during the opening ceremony, satellite communication was utilized for the first time to bring together five choruses from Beijing, Berlin, Cape Town, New York City, and Sydney to perform Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (“Ode to Joy”). Thus, the instances of relational creativity explored in this study concerning the creation and execution of Olympic ceremonies encompass aesthetic, physical, and digital relationalities.

Data analysis

The preceding studies on Olympic opening ceremonies have predominantly utilized textual analyses (Arning Reference Arning2013; Hogan Reference Hogan2003; Lee and Yoon Reference Lee and Yoon2017; Tzanelli Reference Tzanelli2014; Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2005), visual analysis (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Colapinto and Luo2012; Collins Reference Collins2012; de Moragas et al. Reference de Moragas, Rivenburgh, Garcia, de Moragas and Botella1995; Tiganou Reference Tiganou2009), and multilingual media analysis (Lee Reference Lee2021). While each study has employed its unique method, textual and visual analyses share the commonality of focusing on meanings presented either textually or visually (Arning Reference Arning2013). In this article, we expand on this focus on meanings by introducing a framework inspired by the observable creative sense-making (OCSM) method (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Hsiao, Singh, Lin and Magerko2017; Deshpande et al. Reference Deshpande, Trajkova, Knowlton and Magerko2023). This approach gauges the levels of joint sense-making and codes meanings in terms of interaction levels, novelty, and appropriateness (in response to or disregard of a task). We have integrated elements of this method into the abovementioned semiotic methods. Our objective is to identify how relational creativity translates into a repertoire of themes and discern recurring and contrasting themes within the ceremonies. In addition, we aim to explore how relational creativity has influenced the construction of meanings in audiovisual media concerning time, dance, and music.

The focus on relational creativity is pivotal, as previous studies have often considered the construction of meanings in isolation or applied pre-existing frameworks. For example, in-depth analyses of cultural programs have tended to dissect individual ritual components, extrapolating interpretations to the entire narrative (Arning Reference Arning2013). Adopting a relational creativity perspective, we refrain from isolating these elements but instead, examine how individual components relate to the overall structure, and vice versa. Similarly, some research has approached the construction of meaning from a strictly linear rather than a relational viewpoint. Ellis (Reference Ellis2012), for instance, questioned the practice of interpreting Olympic ceremonies in a rigid chronological order. This linear perspective oversimplifies the meaning-making process, especially when considering events in Japan, reducing the rich nuances of national and urban images displayed at the opening ceremonies to a global city endpoint.

The opening ceremony, a complex interplay of meanings, defies easy encapsulation within a singular narrative or framework (Arning Reference Arning2013; Larson and Rivenburgh Reference Larson and Rivenburgh1991). While narrators from various countries offer approximated frameworks for these events, the 2016 flag handover ceremony deliberately subverted this norm by presenting Tokyo wordlessly. This deliberate choice broadened the horizon of meanings, enabling viewers to creatively construct their interpretations. This approach embodies relational creativity, inviting the audience into the meaning-making process (Smith Reference Smith2007). This invitation implies that consumerism as well as cultural consumption of such events is not simply an outcome of relational creativity but is integrated into this process. This suggests that the collaborative nature of relational creativity does not only mean that consumer demands may constrain it but also be utilized for more flexible and adaptive creative processes. This can be particularly advantageous in commercial contexts, where market trends and consumer preferences are still evolving.

Our primary focus rests on the 8-minute performance during the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony, with secondary attention given to the opening ceremony of the 1998 Nagano Winter OlympicsFootnote 3 (the most recent event in Japan prior to the 2020/2021 Olympics). We have selected these two case studies to further explore the notion of relational creativity. As Coates and Coates (this issue) note in their introduction to this special issue, while some consider all human creativity to be collaborative, we examine how relational dynamics not only coordinate and provoke action but also how relational activities can instill and impart established group norms, which may stifle relational creativity. We will use the example of the Nagano Winter Olympics as a case based on relational activities. However, in this case, the relational opportunities sought solutions that aligned with the existing cultural context, thereby not fostering a strong sense of relational creativity. Furthermore, we will examine the 8-minute performance during the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony to demonstrate how practitioners chose to work together through the concept of relational creativity. Therefore, our analysis of Nagano will address the limitations of relational creativity, whereas the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony will present a detailed example of relational creativity in action.

Through semiotic analysis, we examine how these ceremonies served as a canvas for the transformation of Japanese cultural identity and artistic expression through the lens of relational creativity.Footnote 4 Our approach combines OCSM and textual as well as visual analyses of the performances in these ceremonies, exploring their contrasting narrative formats, such as the usage of tradition versus modernity and regional versus metropolitan themes. For some descriptive analyses, insights from stakeholder interviews conducted in 2014 and relevant media articles were referenced. In addition, we consulted the official guidebook of the flagship ceremony and media articles containing interviews with officials and actors related to the opening ceremony.

In essence, our methodological strategy refrains from viewing these events through the narrow lens of pre-existing single or linear narratives. Instead, we emphasize that the meanings of these events must be approached from the perspective of relational creativity, considering the interplay of aesthetic formats and technologies. This approach avoids the simplistic imposition of singular narratives and encourages reflection on strategies that engage the audience within the meaning-making process.

Findings: Olympic ceremonies in Japan

1998 Nagano Winter Olympics: mixing “Japanese tradition” with Western classics

In examining Olympic opening ceremonies in Japan, it is useful to analyze the memorable event held in Nagano Prefecture on February 7, 1998, at the Minaminagano Sports Park. This ceremony, etched in the memory of the present generation, lasted for 2 hours, 4 minutes, and 42 seconds, commencing around 11:00 to align with the United States’ time zone (22:00 Eastern Standard Time (EST)), a significant Olympic sponsor. Unusually, the contents of the ceremony were disclosed in advance, allowing public participation in the initial preparations, featuring traditional events and a live chorus performing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

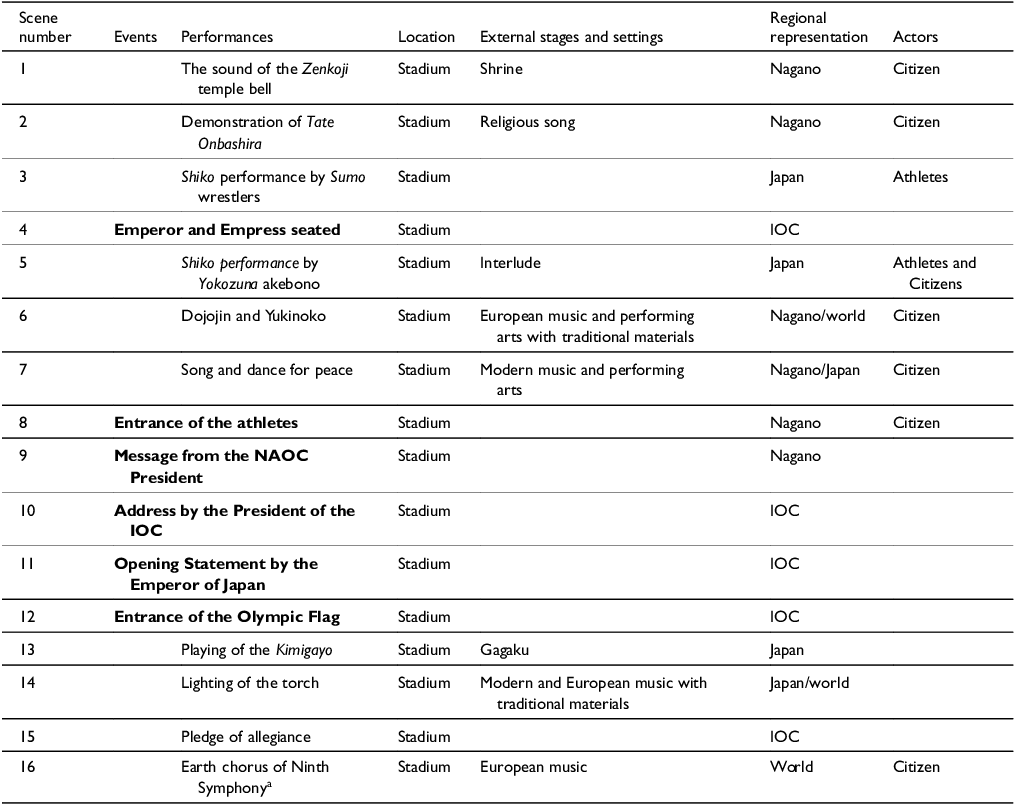

Central to the ceremony was the theme of “Japanese tradition,” a concept that, following Vlastos (Reference Vlastos1998, invented such traditions through intertwining disparate meanings in innovative ways. For instance, the ceremony juxtaposed the meaning of “tranquility” associated with Japanese tea ceremonies with Shiko, presented by 31 sumo wrestlers, in which a wrestler lifts one foot up high before stomping it powerfully on the ground. While Kokugi (national sport, e.g., sumo wrestling), typically representing what is considered to be Japan’s traditional national sport, was briefly showcased, the majority of scenes derived from Nagano’s local culture, transitioning from a top-down nationalist approach to a bottom-up, localized approach. Instead of forcing an existing meaning upon others, this shift embraced the creativity of relational arrangements, combining meanings in novel and diverse ways.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the ceremony; it included four stage themes that constructed traditions and heritage on the basis of Nagano Prefecture’s temples, shrines, and religious events. Specifically, the bell of Zenkoji temple, one of the oldest Buddhist temples in Japan and a symbol of Nagano Prefecture, built in the mid-7th century, was used to signal the start of the ceremony, followed by Tate Onbashira, as the staging of a local Shinto ritual. This performance involves eight colossal logs (two at each of the four corners of the arena) brought all the way to the shrine grounds, being pulled by ropes, with young men climbing them in a sitting position and finally erecting the logs into a standing position. In addition, Dōsojin, the guardian gods of roads and boundaries, and Yukinoko, the snow child, were featured in the scene.

Table 1 Characteristics of the opening ceremony of the Nagano 1998 winter Olympics

a Satellite live broadcasting from Berlin, Sydney, New York, Beijing, and Cape Point.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on Abe (Reference Abe2001) and the Nagano 1998 Opening Ceremony video recordings.

Even though the theme of the festival was a staging of Nagano’s local culture (shown, for example, through the use of straw in the dancers’ costumes, similar to that of Dōsojin), the opening ceremony avoided such homogenous meanings, but creatively rearranged them by including what was presented as Western-derived artistic expressions such as ballet and classical music (scene 6 in Table 1). For example, the stage resembled a sumo ring, which is considered sacred. Akebono Tarō, a sumo wrestler, a native of Hawaii who was promoted to the highest rank of yokozuna in the Sumo Association and became a Japanese citizen, appeared as a symbol of Japan’s “cosmopolitan” nature (Mastumoto Reference Masumoto1998). The staging of such a fusion was also confirmed in scene 14, the torch-lighting ceremony, in which female athletes dressed in modern costumes, resembling Shinto priestesses, lit the torch to the music of Puccini’s opera “Madame Butterfly,” which can be understood as the staging of a mythological scene depicting the image of Ama-no-Iwato (literally, “heaven’s rock cave”). This mythological story involves dance and music to bring light back to the world. It also references the Greek mythology of the lightning ceremony, where priestesses light the torch at the Temple of Hera, associated with the sun god Apollo. The 20-minute-long performance of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” performed under the direction of Seiji Ozawa, a world-famous conductor then working with the Berlin Philharmonic, was the biggest showcase of the festival; using the most up-to-date technology, a live broadcast chorus connected Nagano with Sydney (Opera House), Berlin (Brandenburg Gate), Beijing (Palace Museum), New York (United Nations Headquarters Building), and South Africa (Cape of Good Hope). In addition, the opening ceremony did not only relate meaning in new ways in terms of content and presentation but also employed technology as a form of relational creativity. Musicians who would usually geographically be disconnected from each other were enabled to perform together, using new media technologies and presentation formats. This included exploring a more diverse cultural outlook through implementing localized meanings as well as building connections with other cultural regions through the usage of new artistic formats. Such combinations of technology, art, marketing, and design also imply a commercial creativity, which creates unique value propositions and differentiates these musical outputs from others in the marketplace.

It is perhaps not completely unsurprising that such a relational presentation aimed at configuring new meanings beyond established formats and narratives of national self-presentation caused controversy among the Japanese public. According to Abe (Reference Abe2001), criticism of the ceremony can be divided into three categories: first, the collective embarrassment of presenting a local Nagano event as a “Japanese tradition”; second, the contradiction of having Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, music of Western origin, sung in German while emphasizing tradition; and finally, the extreme exclusion of contemporary Japan. For example, a Japanese TV commentator, Terry Ito, made the following point, “Why couldn’t they have used Honda, Sony, or high-tech robots?” Thus, the project was criticized for being old-fashioned. Responding to a reporter’s question about the divergence between the Japan represented at the ceremony and contemporary Japan, Keita Asari, one of the founders of the Shiki Theatre Company, who was commissioned to provide overall direction for the ceremony said, “High-tech and jeans are not the only things in Japan” (Abe Reference Abe2001).

In conclusion, the Nagano Winter Olympics opening ceremony, while displaying glimpses of relational creativity, struggled to establish a relational meaning-making that bridged the construction of traditional forms of national representation with an alternative version. The commercial strategies employed, including the controversial fusion of cultural elements, led to mixed reactions from the public and media commentators.

Aspirations for the 2016 Rio de Janeiro flag handover ceremony and the “lost” vision for the 2020 Tokyo opening ceremony

This analysis and subsequent criticism of the Nagano opening ceremony is relevant to the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony. In Nagano, the fusion of local, national, and international elements was criticized for being stereotypical and lacking creativity (Tajima Reference Tajima2004). The event further faltered owing to its conservative approach, particularly in its inclusion of new winter sports such as snowboarding, which was viewed as unadventurous (Popovic Reference Popovic2009). The composition of the organizing committee, comprising exclusively elderly men (whose average age was nearly 70 at the time of the event) from politics and corporate sectors, also raised concerns about homogeneity and a lack of diverse perspectives (Hanazawa Reference Hanazawa1999).

In contrast, the 2016 ceremony was led by creatives in their 30s and 40s, well established in the advertising and music industries. Creative luminaries such as Sheena Ringo, MIKIKO, and Kaoru Sugano from Japan’s prominent advertising agency, Dentsu, were entrusted with shaping the event. The ceremony’s theme, “modern Tokyo and invisible traditions,” aimed to encapsulate the essence of contemporary Tokyo, veering away from conventional narratives. MIKIKO said about the ceremony, “I felt that [it is] a real Tokyo of today, [which is a result] of the old-fashioned Edomae. So, I let the musicians do their job as usual, with their wry street sense!” (Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, flag handover segment media guide). Instead of enforcing a single narrative on the performers, the ceremony embraced that meanings would emerge out of their relational creativity (Grant Reference Grant2003). Therefore, the emphasis on music, including globally acclaimed jazz and techno, as well as performance, especially choreography, was unique, as was the choice of Tokyo; the plans contrasted strongly with the staging of antiquated traditions and borrowed classics showcased in Nagano in 1998.

This departure from established norms also distanced itself from the government’s “cool Japan” strategy, which often spotlighted anime and pop idols. Instead, the event spotlighted genuine Tokyoites, such as the underground jazz band Soil and Pimp Session, pioneers in introducing musical instruments to Roppongi’s club scene; they exemplify real Tokyoites (people of Tokyo, the equivalent of Parisians or Berliners) who delved into the culture of jazz and club music to create a new metropolitan culture. Sheena Ringo stated,

I want to use the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympics as an opportunity to “offset and bring to ground zero” the gap between what foreign countries think of Japanese culture, such as samurai, ninja and anime, and what Japanese pop culture currently is. (Interview on the television program “Song”; Japan Broadcasting Corporation [NHK])

While the Rio 2016 ceremony reflected the aspirations of these young creatives, the vision for the 2020 Tokyo opening ceremony encountered unforeseen challenges. The pandemic-induced postponement of the Games prompted structural changes in the organizing committee, including the appointment of Hiroshi Sasaki from Dentsu as the general director. This shift led to the exclusion of the young supervisors involved in the Rio 2016 ceremony’s design. The alterations revealed a conservative and change-resistant facet of Japanese society (see Lemus-Delgado Reference Lemus-Delgado2023), for instance, newspapers such as the Japan Times (March 18, 2021) reported that Mr. Sasaki proposed a plan in which female celebrities would play “the roles of pigs” in the show, which led to his resignation and the disbanding of the young creative team. Despite these setbacks, the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony remained a testament to the innovative aspirations of these young creatives, painting a picture of a Japan evolving beyond the confines of traditional identities portrayed in previous Olympic Games.

Relational creativity and the making of meaning in the 2016 Rio de Janeiro flag handover ceremony

This analysis delves into the intricacies of the 2016 Rio de Janeiro flag handover ceremony, an 8-minute spectacle.Footnote 5 We aim to dissect the ceremony’s core themes and regional representations through the lens of relational creativity, employing a blend of observable creative sense-making (OCSM) and semiotics. To commence our exploration, we offer a descriptive overview of the ceremony captured on video. The official media guide outlined the artistic program in eight segments: “The National Anthem” (01’01’’16); “ARIGATO from JAPAN” (00’36’’25); “TOKYO Is Warming Up” (01’00’’02); “Countdown MARIO” (00’47’’02); “Sports Technology” (03’02’’26); “The City of Waterways” (00’25’’15); “The City of Festivals” (01’25’’00); and “Grand Finale” (00’59’’25).Footnote 6 On the basis of our analysis, we have delineated the performance into three distinct sections: an initial real-time display, a sequence featuring pre-edited video clips, and a final real-time exhibition.

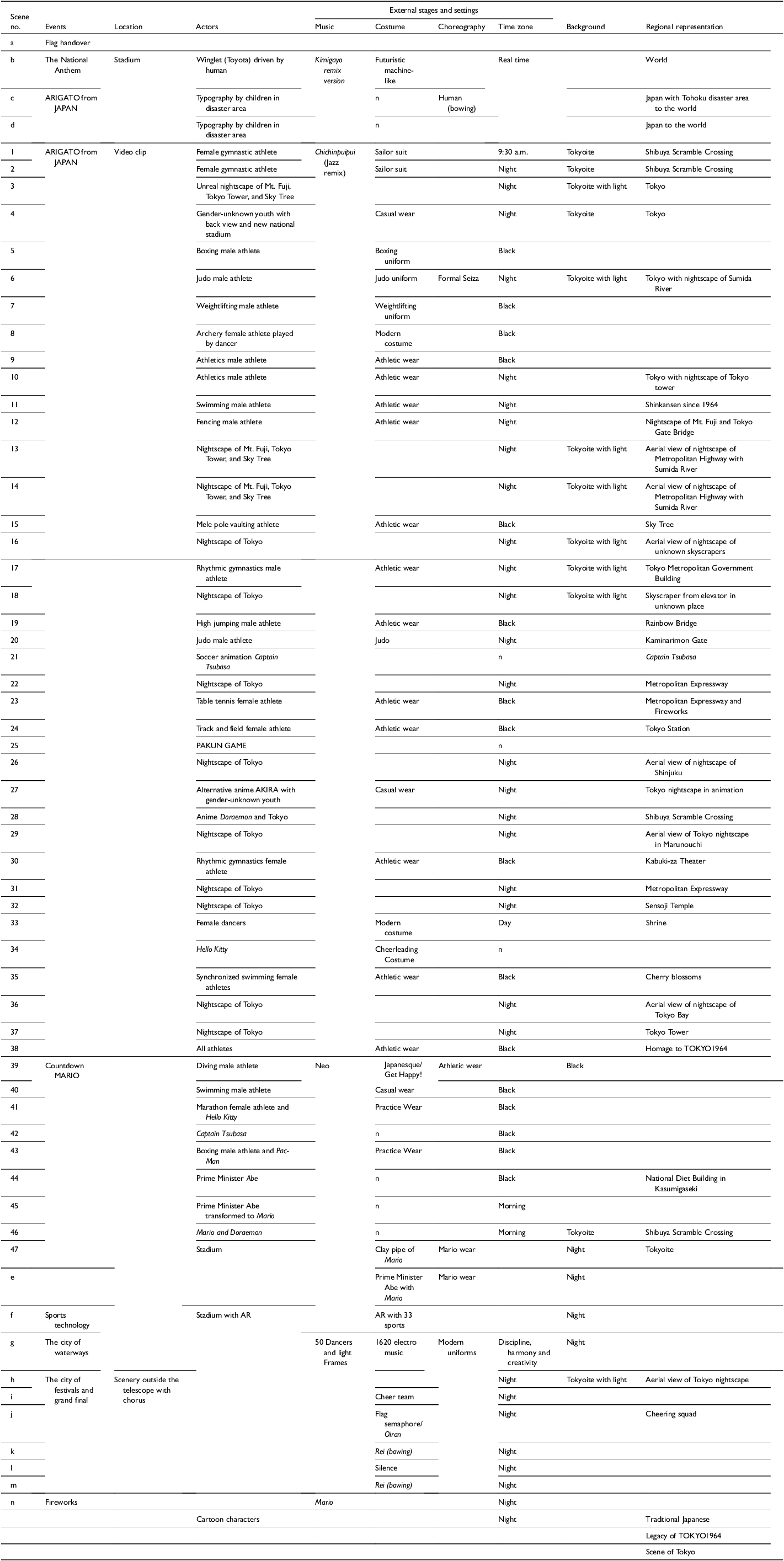

The first real-time performance unfolded across four scenes, followed by a segment of 47 pre-edited video snippets, and culminated in a second real-time display incorporating 10 scenes. In total, there were 61 scenes, each meticulously categorized for our analysis. Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of these scenes, categorized into seven distinct aspects: regional and time representation; actors; and music, costumes, choreography, and media technologies. It is pertinent to note that certain choreographic nuances in the live performance might not have been fully discernible owing to camera angles in some videos. Nevertheless, our analysis remained comprehensive by cross-referencing multiple video sources, including the official NHK video, ensuring a thorough understanding of the intricacies involved. The ensuing section offers an in-depth examination of each scene, emphasizing the seven primary categories delineated earlier.

Table 2 Characteristics of the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony

Source: Authors’ analysis based on NHK’s Rio 2016 Olympics Closing Ceremony video recordings.

“n” means “no data”.

Regional representation: Tokyo and relational creative meaning-making

In this ceremony, the primary focus rests on the Tokyo metropolitan area. The inaugural scene, titled “ARIGATO from JAPAN,” featured children hailing from Tokyo and the three Tohoku Prefectures (Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima), expressing gratitude for the global support following the 2011 earthquake. This fusion of the local and the global seemed to maintain continuity with the Nagano Winter Olympics but also had a distinctiveness of its own. Notably, two scenes showcased the majestic Mount Fuji, while the remainder vividly depicted the multifaceted image of Tokyo. Instead of adhering to a singular narrative, the ceremony embraced a multi-sited approach, celebrating the city’s diverse history and evolution.

Out of the total 47 scenes, a staggering 43 (91%) portrayed urban Tokyo, revealing the intricate layers of the city’s past and present (Table 2). The presentation skillfully weaved Tokyo’s journey, from its rich Edo period heritage to its transformative modernization during the Meiji era and the rapid development spurred by the 1964 Olympics. Iconic landmarks such as the Asakusa Kaminarimon, Sensōji Temple, Sumida River, and Ginza Kabuki-za Theater (featured in seven scenes) are architectural relics inherited from Edo period Tokyo. In addition, Tokyo underwent a significant European influence during the Meiji era, evident in structures such as Tokyo Station and the surrounding Marunouchi area, characterized by brick buildings emblematic of the modern era (featured in two scenes). The preparations for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, envisioned as a means of post-World War II recovery, spurred the construction of vital infrastructures such as the Metropolitan Expressway, Tokaido Shinkansen, Tokyo Tower, and Yoyogi National Stadium (featured in 10 scenes), marking Tokyo’s transformation into a global city during a period of rapid economic growth—a legacy intricately tied to the 1964 Olympics. The western side of Tokyo—embodied by landmarks such as the Shibuya Scramble Crossing, Shinjuku, SkyTree, and the bay area bridges—emerged as the city’s cultural nucleus post the 1964 Tokyo Olympics (a recurrent theme also in the 2020 Olympics), depicted in seven scenes. The representation of Tokyo extended beyond mere physicality. In virtual reality cutscenes inspired by the Shōwa-era cyberpunk anime AKIRA, a futuristic Tokyo came to life, portraying the city’s vibrancy and ambiguity through neon lights and enigmatic landscapes. The vivid depiction of Tokyo’s landmarks and urban landscapes in the ceremony can be interpreted as a showcase of the city as a hub of consumerism and modern lifestyle. Places such as Ginza and Shibuya are not only cultural icons but also symbols of Tokyo’s status as a global shopping destination. This dual representation appeals to both cultural tourists and global consumers, aligning with the city’s objective to attract visitors and boost economic activity through tourism and consumption. This nuanced imagery rejected a monolithic perspective, embracing Tokyo’s polycontextural nature. This approach recognizes that the observation of a phenomenon, particularly a city as dynamic as Tokyo, is not confined to a singular viewpoint but is rooted in a more expansive relational creative meaning-making process (Löw Reference Löw, Smagacz-Poziemska, Gómez, Pereira, Guarino, Kurtenbach and Villalón2020).

Time representation: nighttime and relational creative meaning-making

In terms of time representation, a predominant theme across live performances and pre-edited videos was the depiction of nighttime scenes, constituting nearly half of the content (Table 2). The pre-edited video commences with a glimpse of the renowned Shibuya Scramble Crossing at 09:30 a.m., highlighting the 12-hour time difference with Rio de Janeiro. Subsequently, the screen is flooded with a flurry of nighttime images, with 7 out of the 23 nighttime scenes featuring skyscrapers. This intentional emphasis on the nighttime setting can be attributed to the unique creative opportunities it presents. Tokyo, bathed in artificial illumination from various sources such as apartment window lights and car headlights on highways, creates a captivating visual spectacle during the night. In this nocturnal ambiance, the rigid boundaries and well-defined structures of the day blur into abstract forms, providing an ideal backdrop for innovative and daring ideas to surface. This portrayal taps into the desire for immersive experiences that characterize contemporary consumer society, where cities are not only places to live but also to consume visually and culturally. The night, shrouded in shadows, becomes a canvas where nascent and audacious concepts can be freely shared and explored in a more relaxed atmosphere (Morgner and Ikeda Reference Morgner, Ikeda and Garcia-Ruiz2020). As Tokyo enhances its nighttime economy, attention must be paid to inclusivity and access. The benefits of a thriving nocturnal culture should be available to all segments of society, including workers, residents, and visitors. In anticipation of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the Japanese government implemented policies to boost its nighttime economy, easing regulations related to clubs and music venues, particularly to enhance the experience for inbound tourists (Ikeda and Morgner Reference Ikeda and Morgner2020). This deliberate focus on the nighttime scenes not only accentuates the city’s vibrant energy but also underscores the significance of the night as a symbol of creative freedom and exploration (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Night-time scenes during the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony.

Actors and relational creative meaning-making

In stark contrast to the Nagano Olympics, the flag handover ceremony for the Tokyo Games featured a diverse ensemble of actors. This group comprised a wide array of athletes, both active and retired gold medalists, taking center stage in the video clips. In addition, the performances included 50 dancers distinct from the realm of Olympic athletics. In select pre-edited video scenes, the backdrop was adorned with the presence of ordinary city residents and cars, subtly enhancing the authenticity of Tokyo’s portrayal.

The selection of actors was meticulous, aiming to offer a balanced and inclusive representation of genders. Approximately 15 scenes featured male athletes, eight spotlighted their female counterparts, and an additional eight showcased beloved Japanese cartoon characters, including two enigmatic youths with their backs turned to the camera. The pre-edited video commenced with a vibrant rhythmic gymnast embodying a high school student performing gymnastics in a sailor suit at the iconic Shibuya Scramble Crossing. The second scene featured a young individual of undisclosed gender, their back to the audience, adding an intriguing layer of mystery. Noteworthy inclusions were two openly gay actors, freely expressing their relationship in one of the video scenes.

Furthermore, the ensemble featured iconic characters from renowned Japanese animations and games, including Captain Tsubasa, Pac-Man, Doraemon, Mario, and Hello Kitty, emphasizing the global recognition of these distinctly Japanese creations. This thoughtful gender representation within the ensemble did more than present a diversified approach; it deliberately avoided narrating Tokyo’s story through a single voice. Instead, the actors collectively wove a narrative, akin to a harmonious chorus, where each voice responded to the others—a creative endeavor reminiscent of improvised dance forms (Loji Reference Loji2021). While leveraging popular culture icons and diverse representation effectively engages global audiences, it also presents the challenge of balancing authentic cultural representation with commercial appeal. Ensuring that the use of cultural symbols and narratives does not veer into cultural commodification or stereotyping is crucial for maintaining cultural integrity and respect. This intentional choice amplified the richness and complexity of Tokyo’s representation, showcasing the city’s multifaceted identity through a diverse and vibrant cast.

Relational musical meaning-making

The musical composition for the ceremony comprised six pieces intricately remixed from diverse global sounds, including a modern rendition of the national anthem, Kimigayo, and the universally recognized theme of Super Mario Brothers. The opening piece, Kimigayo, was meticulously arranged by Jun Miyake, a renowned composer and jazz trumpeter with studios in Paris, New York, and Tokyo. Notably, this arrangement of Kimigayo, rarely heard in Japan, featured a Bulgarian voice, a choice attributed to its somewhat “taboo” nature, as shared in an interview with Jun Miyake (ARBAN, May 1, 2019). Miyake stated,

What I had in mind was to bring out the original beauty of the melody first. While keeping Eastern European harmonies as the base, we wanted to hybridize elements of gagaku, modern classical music, and other Western influences, as well as jazz influences. Also, a stadium environment inevitably has a lot of reverberation, so when complex harmonies are layered on top of each other, they become muddy. As a countermeasure, we put in pauses so that the sounds would at the very least not clash. Also, the Bulgarian voice has riffs and runs, which is similar to that of Japanese folk songs, so I tried to use it as much as possible. This time, the arrangement is in four voices, but in the beginning, instead of everyone doing riffs and runs, we tried various ways, with the top voice’s runs or the lower voices’ runs, but this did not remain in the final form. (Interview with Jun Miyake, ARBAN, May 1, 2019)

In the subsequent scene, “ARIGATO from JAPAN,” Miyake’s musical prowess continued through his composition, “Anthem Outro.” Moreover, the ceremony featured arrangements by Yoichi Murata, under the musical direction of Sheena Ringo. Collaborating with the Japanese underground trio H ZETTRIO on the piano Torio band, Murata crafted adaptations of “Neo Japanesque” and “Get Happy!” In addition, the renowned techno-pop composer Yasutaka Nakata contributed his expertise with “1620.” The repertoire concluded with a jazz interpretation of Sheena Ringo’s creations, “The City of Festivals” and “The Telescope Outside View.” Remarkably, these compositions, excluding the national anthem, not only celebrated Tokyo’s diverse essence but also exemplified a profound understanding of music creation as a collaborative endeavor.

Within these collaborations, the boundaries of individual contributions dissolved, giving rise to a phenomenon deeply rooted in collective efforts. Examining these creative avenues through a relational lens revealed a symbiotic relationship, where collaborative endeavors continually nurtured and inspired the very collaborations that birthed them (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Smith, Vistic and Glăveanu2022). This musical symphony, a testament to relational creativity, resonated with the ceremony’s ethos of relational meaning-making. While the ceremony’s music promotes cultural exchange and appreciation, it also reflects a broader trend of cultural commodification in consumer society.

Costumes and relational creative meaning-making

In the visual tapestry of the ceremony, costumes emerged as significant vessels of creative expression. Competition and practice uniforms are used in 19 of the 47 scenes in the video, consistent with the athletes-first concept. The only staging of traditional costumes used are judo uniforms; in the stadium scenes, tradition is represented indirectly. First, the first four scenes in the stadium include costumes inspired by Japanese origami to create a futuristic costume made of Japanese paper, incorporating valley and mountain fold pleats angled to fit the form. Headpieces and corsets inspired by a bride’s cotton hat are also used here. In the latter three scenes in the stadium, the costumes are all in gray, and in the transition to the latter seven scenes, a quick change inspired by the “Hikikiri” of Kabuki theatre is made. In the climactic scene, the “Cheering Squad,” “Omotenashi,” (“to wholeheartedly look after guests”) “Hand Flag,” and “Aomori University” groups use costumes that “mixed the casual and street feel of Tokyo while incorporating graffiti and harness elements in the tops” (Fashionsnap, 13 September 2016). Costumes and hairstyles (men’s hairstyles and wigs for the female dancers) are designed with the contemporary era and near future in mind on the basis of Japanese school uniform culture. While this may seem at first glance to lack individuality, it expresses cultural changes in Japanese fashion; by wearing neither the kimono nor Western business wear, each person is slightly different from the others. As the ceremony’s costumes become a focal point for representing cultural heritage and contemporary design, considerations around the ethical production of these garments come to the forefront. Ensuring that costumes are produced in ways that are fair, ethical, and sustainable can further enhance the ceremony’s appeal to a consumer society increasingly concerned with the ethics of their consumption choices. In addition, cheering is considered a part of sports, which can be understood by the incorporation of elements of cheering cultures in the costume designs and choreographies. It is interesting to note that the seifuku-like costumes (modeled after Japanese schoolgirl uniforms, which are based on European-style naval uniforms), which at first appear to conform to gender norms, are in fact designed to be genderless. Note that three colors—deep vermilion and white used in the Japanese flag, and gray, representing the metropolis of Tokyo—are incorporated in the costumes. These colors are also used uniformly in the video. In essence, clothing ceased to be a mere shield against the elements; it transformed into a canvas of expression, telling stories of cultural evolution, diversity, and societal dialogue. In this sense the meaning of fashion is not just an individual matter, because it is also a signal to others, and has a relational quality, e.g., the uniform of a police officer signaling authority.

Relational creative meaning-making through choreography

Finally, choreography is used to stage the intangible traditions and history of Japan, such as bowing, thanking, the culture of sitting, and hand signals, which, along with the music and costumes, constitute the most important artistic elements of this cultural event. Choreography can be understood as a form of both sport and art. Similarly, the postwar Japanese culture of cheering, known as ōendan, is implied in the choreography of this performance. For instance, the initial scene explores the concept of human-operated mobilities. Individuals converge at the stadium’s center, collectively forming the outer edge of a circle symbolizing the national flag. Performances by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and children from disaster-affected areas accompany this formation. In addition, the Japanese tradition of “bowing” is showcased as a gesture expressing gratitude for the global support extended after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. In the stadium, the images of the 33 competitions directing the acrobatics and scenes from each sport are represented. What is expressed as choreography is the discipline of the Tokyoites. For example, outside the frame, the dancers perform mechanical movements, while inside the frame, they dance lightly and freely. Crucially, the choreography refrains from imposing hierarchy upon the diverse elements at play. Instead, it embraces a creative interplay where no single element prevails over the other. The deliberate inclusion of diverse elements and the absence of a hierarchical structure in the choreography mirror contemporary consumer values of inclusivity and equality (Fisk et al. Reference Fisk, Dean, Alkire (née Nasr), Joubert, Previte, Robertson and Rosenbaum2018). This intentional absence of hierarchy fosters a relational creativity that is both open-ended and nonprescriptive. The choreography becomes a canvas for exploration, where multiple meanings intersect and diverge, encouraging viewers to interpret the performance in their unique ways. In this open-ended approach, the choreography sparks a multitude of emotional responses, emphasizing a relational creativity that thrives on its ability to evoke diverse and nuanced reactions from the audience.

Media technologies and relational creative meaning-making

In addition to the large-scale projection mapping and linked performances from the opening ceremony, the flag handover ceremony featured augmented reality, human mobility, light technology on costumes, and LED frames that emit a unique light as they move. The LED frames were realized with technology developed by Daito Manabe from software for the competition (Fashionsnap, September 13, 2016). These technologies linked to the performances were developed by MIKIKO and Manabe, who were the general directors, through concerts of the Japanese techno-dance unit Perfume and other events before the Olympics. Manabe said, “The projection, AR, VR, MR (mixed reality), and other visual images and sounds, hardware and software such as drones, and flesh-and-blood humans. How to relate all these elements together in a creative way? The ‘live’ performance staging at the Rio Olympics was, so to speak, the culmination of what we had cultivated through that experience” (Nippon.com, March 15, 2018). In contemplating the essence of creativity, it is essential to broaden our perspective beyond the human realm. Actor–network theory, a framework adept at understanding complex interactions, reminds us that non-human agents, such as advanced technologies, play an active and indispensable role in shaping meaning (Bartles and Bencherki 2020). These technologies cease to be mere tools; instead, they become dynamic participants in the creative process. As active translators and facilitators, they forge connections between diverse elements, seamlessly blending visual imagery, sounds, and the palpable presence of human performers. The integration of media technologies in the ceremony highlights the shift in how cultural products are consumed in the digital age. Consumers increasingly seek out digital and technologically enhanced experiences, blurring the lines between physical and virtual spaces (Dulsrud and Bygstad Reference Dulsrud and Bygstad2022). The ceremony, therefore, not only contributes to the cultural tapestry of the Olympics but also reflects changing consumption patterns where digital experiences are highly valued.

Discussion: new Olympic representations and polycontexturality—Tokyo, Tokyoite, and relational creativity

In analyzing Olympic opening and closing ceremonies, our exploration was grounded in the paradigm of relational creativity—an innovative lens for experimenting with fresh meanings and artistic expressions. Notably, we focused on the often overlooked narratives from Japan’s peripheral Olympic ceremonies, unearthing depths hitherto unexamined. Through a meticulous content analysis juxtaposing the 1998 Nagano Olympics and the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony, we assessed myriad examples of creative relational meaning-making inherent in Japan’s self-image within the context of Olympic ceremonies.

We used a focus on relational creativity within these ceremonies to unravel the intricacies of relational experimentation, exploring the nuances of self-presentation, the propensity to forge new meanings through relational ideas, and to dissect the ingenious utilization of media technologies in profoundly creative ways. This strategy not only promotes Japan’s image internationally but also taps into the lucrative market of cultural tourism and related consumer products. Within this analytical framework, our exploration illuminated shared traits between the ceremonies at Nagano and Rio—a distinctive absence of a linear national narrative, a facet traditionally emphasized in preceding studies on Olympic ceremonies. However, a closer examination highlighted the stark differences in their approaches concerning traditions, nuances that profoundly influenced the portrayed meanings.

First, the Nagano Olympics adopted Western-derived classical music and performing arts, as well as themes related to local folklore and mythology. This resulted in a single narrative based on a fusion of constructing Japanese traditions and Western culture; the former was expressed in the stage theme and the latter in the music, costumes, and performing arts. There was also an awareness of intensity in the music. The ceremony began with a relay from Zenkōji Temple, where the silence created by the sound of the bells consumed the space, and developed into the Ninth Symphony, where the citizens of Nagano were connected to cities around the world via simultaneous relay, interspersed with the ritual of the Onbashira and pop songs. If we understand that every performance, as well as the order of performances, has a meaning, we can read a linear relational development from Japan to the rest of the world.

In contrast, the Rio flag handover ceremony combined and juxtaposed the cultural legacies of the Edo, Meiji, Showa, and Heisei eras, which continue to resonate in everyday life, with artistic compositions in buildings, animation, and design composition (Fig. 2) and performances ranging from music to choreography. There was no emphasis on a particular meaning taking precedence over another. In particular, in describing “invisible traditions,” the depiction or use of specific cultural heritage as film location was avoided. What was adopted instead as a representation of Japan was not a single narrative but a multitude of creative relational expressions through music, costumes, and choreography. Likewise, the costumes, while inspired by traditional motifs such as the bridal cotton hat and school uniform, experimented with a range of different expressions, at times in quite subversive ways. Furthermore, the choreography also experimented with different culture expressions, such as bowing, the culture of sitting, and modern Japanese communication through “uchi” (inside) and “soto” (outside).” In addition to the culture of cheering groups and hand flags, the advancement of media technology added different layers of creativity on the basis of the integration of these technologies. If Japan in the 1990s, represented by Nagano, intended to transmit messages to foreign countries, the delayed Olympics of 2020 aimed at a more polycontextural presentation (Knudsen Reference Knudsen2017), where multiple frames of reference that adhere to distinct codes coexist and interact. Relational creativity emerges as these diverse viewpoints interact and blend, fostering the generation of novel ideas and interpretations. The arrangements of creative observations in a polycontextural context are heterarchical, meaning there are no fixed hierarchical relations between different creative expressions. Unlike traditional hierarchies where certain forms of creativity might be deemed superior to others, polycontextuality implies that creative contributions are valued within their specific contexts. Such a polycontextural presentation of the Olympics in 2020 could have been possible based on the evidence from the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony but remained a “lost idea.”

Figure 2: Scenes of Olympic legacies in posters (left: 1964; right: 2016).

In line with Edensor’s (Reference Edensor2006) point, we demonstrate that when understood through the lens of relational creativity, the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony experimented with new ways of making meanings. Rather than dominant linear depictions of national chronology that overemphasize “official” history, tradition, and heroic narratives, a sense of identity and belonging is maintained through polycontextural representations. In turn, these new polycontextural representations can perhaps also be a reproduction of a new kind of “national” identity. By analyzing the new Olympic representations through the lens of relational creativity, we could also deepen our understanding of how these ceremonies navigate the complex terrain of global consumer culture. By reflecting on the ceremonies’ roles in shaping and responding to contemporary consumption patterns and societal norms, we can appreciate the multifaceted ways in which global events such as the Olympics contribute to the ongoing dialogue between cultural expression and consumer society dynamics. We can, therefore, conclude that the Rio 2016 flag handover ceremony, with its relational creativity approach, opened up a more polycontexual representation, which even included a challenge to, or contesting visions of, a harmonious society, presenting a stimulating moment with regard to international events in Japan.

Financial support

We are grateful for the support of the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 19KK0020 and JST SAKIGAKE JPMJPR21R1.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Biography

Dr. Mariko Ikeda is associate professor at the institute of Art and Design, University of Tsukuba. She is a cultural geographer specialising in cultural research in Germany and Japan.

Dr. Christian Morgner is a Senior Lecturer at the Management School, University of Sheffield. He has been a visiting fellow at institutions including Yale University, Keio University, the University of Leuven, and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris). Using Grounded Theory, his research on the global formation of media events led to the monograph Global Media Events and numerous papers, exploring how media meanings are created globally. His work also integrates video analysis, bridging sociolinguistics, healthcare studies, and conversation analysis.

Dr. Mohamed Nour El-Barbary is a lecturer at the Center for Tourism Research, Wakayama University. His research interests include cultural heritage, human geography, tourism studies, and linguistic landscapes, focusing on Egypt, Japan, and Germany.