“Devoting all efforts to become a city where people shine.”Footnote 1 This phrase, and similar iterations, are a recent and popular theme found in assertions by Tokyo’s governor, Koike Yuriko.Footnote 2 The claim, also framed as “a city where no one is left behind,” appears frequently in policy documents, official reports, YouTube videos, and other public-facing communications from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government,Footnote 3 all of which seem to be wonderful—on the surface. Who is not in favor of fostering a city and society where everyone can “shine” (kagayaku) and no one is left behind? Yet many of the governor’s actions and alliances while in office since 2016 suggest that her administration is committed to many proposals and actions that, in fact, bring about the opposite reality—they foment a Tokyo where a great many are left dimmed, leaden, and behind. Governor Koike’s methodical assault on public green spaces throughout the capital, coupled with grotesquely insufficient engagement with Tokyo’s unhoused and long-standing reticence to meaningfully address poverty, inequity, and gendered discrimination all betray a contemporary reality where many fall behind without the possibility to “shine” (Goto et al. Reference Goto, Culhane and Marr2022; Penney Reference Penney2024).Footnote 4

My position here, rooted in ethnographic work with Tokyo-based advocacy groups for the unhoused and marginalized (to be discussed later) is that the governor’s recently favored assertions are best read as a performative act of future-making. An act in line with decades of similar efforts that endeavor, through vapid proclamations, to obstruct and occlude consideration of meaningful alternatives to the prevailing social order. Framed this way, it becomes unequivocal that absurdity organizes Japan’s future-making practices, as it reveals the incompatibility between contemporary proclamations by governing institutions and daily lived realities—a situation that is best captured in the increasingly elaborate, yet hollow, future-making projects offered to the Japanese public as a solution to persistent societal concerns.

Future-making

As observers of Japan are no doubt well aware, the turn of the millennium initiated a now decades-long series of large-scale proposals oriented toward a future of shifting specificity that continues to be put forward as, at best, questionable solutions to seemingly intractable issues of broad concern. Health(y) Japan 21, launched in 2000, initiated a process that sought compliance with the then emergent neoliberal project’s demands of “self responsibility” (jiko sekinin) all the way down to the level of individual bodies and responsibility over their management (Alexy Reference Alexy2020: 52; Borovoy Reference Borovoy2017; Nomura et al. Reference Nomura, Sakamoto, Ghaznavi and Inoue2022). Suited salarymen were the default visual depiction, often shown in demeaning situations where belly circumference was publicly measured and recorded in offices as an indicator of overall health. The state’s retreat from healthcare provision was coupled with demands for individual responsibility around diet, smoking, alcohol, and exercise in an effort to lessen future burdens of care provision without addressing systemic concerns of overwork, stress, and expectations of alcohol-mediated socialization (Borovoy and Roberto Reference Borovoy and Roberto2015).Footnote 5 Through workplace exams, “Japanese workers are annually reminded (by the national government) that their bodies may be out of shape, out of compliance, and out of conformity” (SturtzSreetharan et al. Reference SturtzSreetharan, Trainer and Brewis2022).

Health(y) Japan 21 was followed by Innovation 25, Society 5.0, and most recently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Notably, each of these initiatives appeared with great fanfare before sliding increasingly into bureaucratic oblivion, often when target years arrived with little to no tangible, recognizable outcomes concerning the goals and possibilities put forward years earlier. Jennifer Robertson’s consideration of robotics neatly unveils this tendency in her analysis of Innovation 25 and its reliance on “retro-tech,” which she defines as “the application of advanced technology in the service of traditionalism” (Robertson Reference Robertson2018: 23). A techno-utopian solution to Japan’s falling birth and marriage rates is offered through infinitely capable robotic housekeepers who electronically embody all the traits and practices captured in the oppressive “good wife, wise mother” (ryosai kenbo) ideology of earlier generations (ibid.: 79; White Reference White2002: 43). As the target year has arrived and home care robots with even a fraction of the capabilities depicted in official promotional material exist only in science fiction fantasies, the remaining analytical question is to scrutinize the point and purpose of this future-making exercise (Wright Reference Wright2023: 11). Did future depictions of domestic tranquility and ample leisure time through the introduction of home care robot companions represent goals deemed ambitious yet achievable? Or was this an exercise in official distraction from systemic dimensions of root causes to social concerns with the additional bonus of manipulatively reviving restrictive gender norms while offering the appearance of forward thinking?

As attention to Innovation 25 faded (it was initiated in 2007), a larger and more ambitiously pitched program was put forward in 2016 as Society 5.0. As with the two previous proposals, the scale and scope increased substantially. Society 5.0 was offered as the “next stage” in human evolution (The 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan: 12). Described as the creation of a “super smart” society of the future—a future where concerns tied to an aging and shrinking population have been resolved through as yet impossible technological advancements predicated on frightening surveillance expectations—Society 5.0 is less newly innovative and more a perpetuation of an established template. A template with the principle objective of obscuring—through a “technopolitical instrument of affect”—an idyllically rendered near future to sustain and expand an austerity-driven project unequivocally opposed to anything but a market-driven orthodoxy of growth, no matter how absurdly impossible and immediately harmful such an approach continues to be (Lindtner Reference Lindtner2020: 18). The abundance of promotional material, typically disseminated through government or corporate channels, is laden with technical jargon—artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things (IoT), science, technology, and innovation (STI)—alongside expertly produced videos depicting a blissful near future devoid of contemporary concerns.Footnote 6

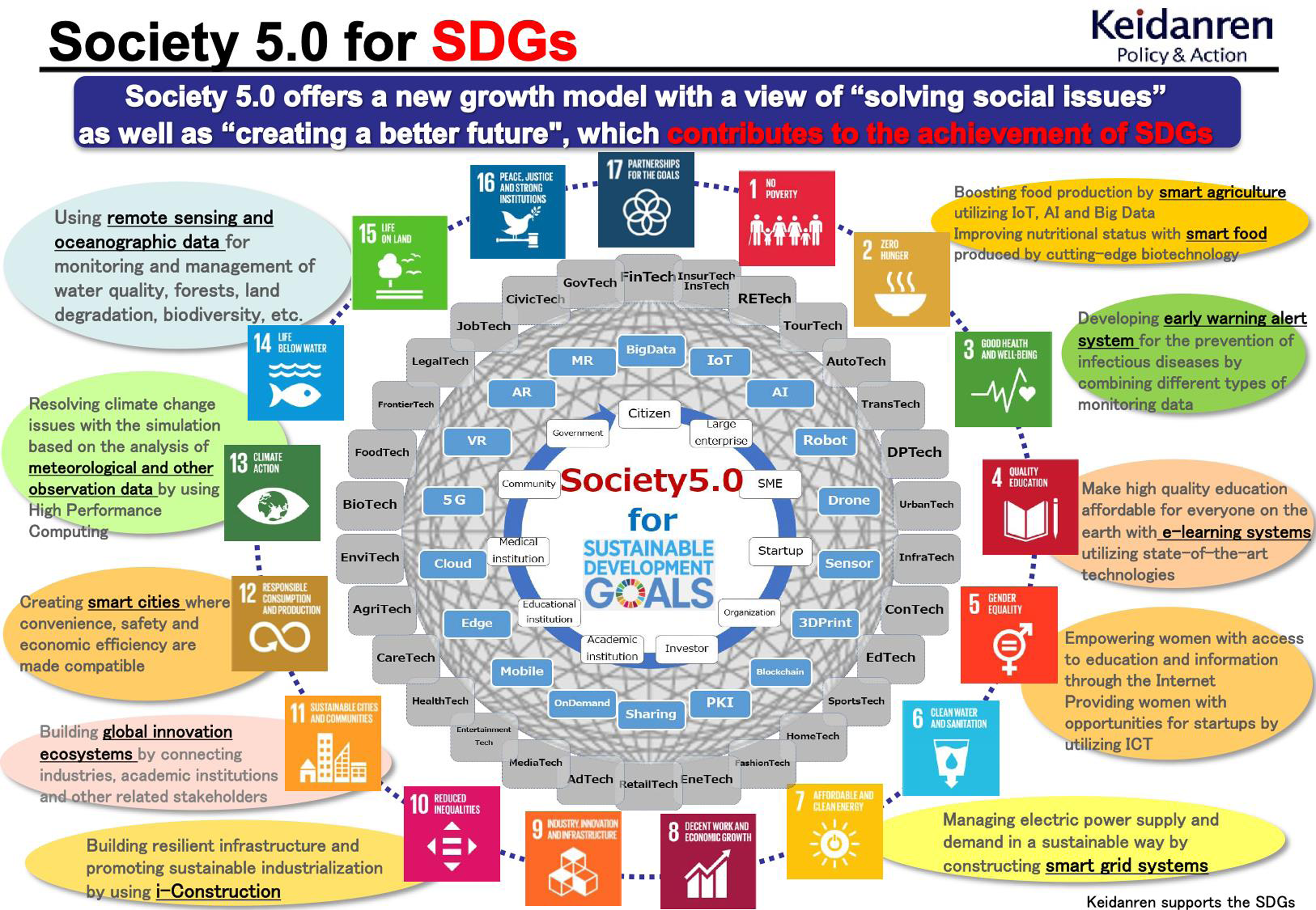

Finally, Society 5.0 has found a productively deceitful partner in the Japanese government, as well as aligned corporate and lobbyist groups, eager to disseminate the United Nations (UN)-initiated SDGs in a highly particular manner. The SDGs were adopted by UN Member States in 2015 as a “blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.”Footnote 7 Laudably, the SDGs forcefully assert the necessity of “ending poverty and other deprivations” as the principle means of achieving the goals. Of the 17 goals, the first is “No Poverty” and the second is “Zero Hunger,” reflective of the stated orientation to alleviating human suffering and marginalization worldwide—all of which makes Japan’s vocal embrace of the SDGs, itself unusual globally, suspect as scrutiny of how such efforts have unfolded reveals manipulation of the goals in the interest of varying industries, particularly construction, with negligible attention to poverty or inequality reduction throughout Japan (Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, SturtzSreetharan, Crabtree and McClean2025). A 2017 presentation slide from Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) captures the intricacy of the orchestrated absurdity put forward in efforts to merge Society 5.0 and the SDGs as a future-shaping project (Fig. 1).Footnote 8 No Poverty, the first and fundamentally orienting goal, is ignored entirely. Gender Equity, rendered into a relational category and conflated with women, is reduced to expanded internet access as the means of resolving issues of inequity without any mention of patriarchal or systemic considerations. Reduced Inequalities is also ignored entirely while frequent mention of empty jargon—“sustainable industrialization,” “smart cities, food, agriculture, and grid systems,” and “global innovation ecosystems” (whatever that means)—abounds. The bewildering complexity of the image seems to correlate with the degree of deception needed to obscure how much effort is necessary to justify the current order and thereby refuse consideration of anything meaningfully different now or projected forward into the future.

Figure 1: Keidanren presentation slide of “Society 5.0 for SDGs.”

Now considered as a several-decades-long trajectory, these projects are undeniably intended to shape perceptions of the coming future in particular ways. Most relevantly, by shifting collective notions of responsibility onto individuals, no matter their circumstances. Harnessing a retro-futurism seems forward-looking and progressive, yet it eagerly reasserts particular and restraining values of gender and work while perpetuating reliance on unrealized technical solutions to areas of social concern to delegitimize consideration of more human-oriented alternatives (Robertson Reference Robertson, Bruun, Wahlberg, Douglas-Jones, Hasse, Hoeyer, Kristensen and Winthereik2022). These projects look less like the ambitious assertions of a technically sophisticated nation eager to transcend the limits imposed by existing technological capabilities and more like desperate performances of legitimacy by aligned organizations slavishly committed to a failing orthodoxy, despite awareness of growing popular recognition around the deceitfulness of perpetuating such an approach.

Alternative-making

Turning official proposals intent on dictating visions of Japan’s future into recognition of the unceasingly fanciful absurdity determined to thwart consideration of alternatives requires shifting focus to groups working to bring about a more dignity-oriented collective existence. In notably different ways, Sanyukai in San’ya and Tenohasi in Ikebukuro work in a modest yet determined manner to ensure that it remains possible to conceptualize a future that differs in meaningful ways from those typically put forward in official capacities.Footnote 9 Both groups do weekly, conventional outreach activities, including takidashi (food distribution), yomawari (wellness checks in areas where Tokyo’s unhoused are known to concentrate), and seikatsu sōdan and iryō sōdan (livelihood and medical consultation).

The practical necessity of these outreach activities is undeniable and seemingly growing. Sanyukai, which operates from a base in Tokyo’s San’ya area, a part of the city long associated with poverty and despair, recently has experienced increases in the number of people seeking food each week. Sanyukai posts regular video updates of recent activities to its YouTube channel, and the 6-minute clip from November 30, 2024 discusses the rise in the number of new people requesting food.Footnote 10 Tenohasi also reports a recent increase in the number of those seeking food, with more than 600 coming to a takidashi in Higashi Ikebukuro Central Park on November 23, 2024 (an increase of almost 100 people from the same outreach event held 2 weeks earlier). What is unequivocally clear is that, despite the governor’s assurances, many throughout Tokyo are being left behind, and those directly working to stanch the hunger and need report that the number of those in need is expanding.

However, I want to turn away from a straightforward ethnographic consideration of the practical aspects of support work directed toward Tokyo’s unhoused and hungry, although such an accounting is important and worthy of dissemination. Instead I want to shift toward how these groups represent a crucially important challenge to thinking about and depictions of the future. Pervasive future rendering through a Society 5.0- or SDG-shaped lens takes to a digitally rendered world the “tokubetsu seisō” (special cleaning) that periodically displaces the homeless from, famously, Ueno or other major parks throughout Tokyo prior to a visit by a member of the Imperial family, prominent political figure, or anyone who would benefit from claiming that homelessness and poverty are issues irrelevant to Japan (Margolis Reference Margolis2002).Footnote 11 A Keidanren video from 2020 titled, “Our Future” (watashitachi no mirai), references both Society 5.0 and the SDGs. It puts forward a future where a Japanese surgeon performs robotic-enabled surgery on a boy at his home in what appears to be a vaguely Middle Eastern/South Asian setting. Afterwards, she meets French-, Chinese-, and Hindi-speaking friends at a stylish (and surprisingly diverse) Tokyo café where the need to learn each other’s language has been eliminated through in-ear simultaneous translation devices.Footnote 12 These translation capabilities are so sophisticated that even the barks of the Hindi speaker’s pet dog (that we learn is bored at the café and wants to go play in the park) can now be rendered into clear, declarative Japanese.

What is absent from this marvelous, inter-species communicating future is despair or poverty. Yet how is that possible if nothing being proposed even acknowledges that such realities exist, let alone meaningfully includes substantive steps to eradicate poverty and despair in the shaping of what is to come? No matter how enticing and fanciful the video depiction may be, it and others are still governed by the same logic as the crude cudgel driving park sweeps, hostile architecture, and other practices intended to eliminate from view instead of meaningfully address with empathetic concern the plight of those who suffer under the austerity of Japan’s enduring commitment to market irrationalities (Andrews Reference Andrews2020; Kitagawa Reference Kitagawa2021).

Such elaborate depictions are what make the work of outreach groups essential in ways that transcend their daily practicality and provision of life-sustaining nourishment. Their work represents the preservation of the potential of an alternative—that creating groups, networks, and even societies oriented toward dignity, endeavoring to ensure that all are fed and housed, and operating on principles other than monetary allocation are not just possible but necessary. Meanwhile, the effort undertaken to obscure this basic recognition is staggering. The outreach event that attracted more than 600 people in late November 2024 has also been displaced from its original site at Minami Ikebukuro Park after an SDG-referencing “redevelopment” project made the presence of the unhoused or any attempt to provide them with services impossible. In doing so, the SDGs, organized around poverty eradication through meaningful aid, was fully perverted into a gentrifying force that displaced and sought to delegitimize—but crucially could not erase—in the name of a program that claims to seek the opposite.

Conclusion

In the spring of 2022, I was one of the many volunteers at Higashi Ikebukuro Central Park, helping with the event that now experiences greater demand for its services than ever before. Typically, I was given the task of assisting with iryō sōdan (medical consultations), largely because my lack of tangible skills was easily overcome by the eminently capable volunteer nurses and other medical professionals with whom I was paired. Often my role was little more than being a person with an additional set of sympathetic ears who could hold tired legs while expert hands attended to injuries and bandaged festering infections. The most immediately ethnographic conclusion from my sessions as a volunteer was that many in Tokyo are being left behind, and the reasons driving this sad and avoidable reality are modest in scope but impossible to address in the prevailing ideological setting predicated on concealing instead of confronting cruelty. A reality where ingrown toenails are an unremarkable yet insidious affliction that can render a high degree of incapacitation because frail and elderly individuals live alone and lose the strength, dexterity, and flexibility to attend to them. Poverty compounds the troubles that arise, and periodic painful shuffles to outreach activities become one of the only means of finding some relief. Those who gather in this park or in San’ya have sores that do not heal, anguish that debilitates, and hunger that saps all forms of function and vitality.

Critiques of the position I take here will likely coalesce around the absence of a clear articulation of the practicalities required to achieve the alternative I call for. Such critiques, however, miss a crucial point: We are at a place where defense of an alternative is the necessary dimension, as it is what stands between the collective and a reality where any who defy or diverge from the increasingly impossible normative expectations are erased. It has become fashionable in intellectual circles to speak of Japan as a “harbinger” of what is to come across the Global North (Lipscy Reference Lipscy2022). If we accept this framing, alongside Governor Koike’s public assertions, then what awaits is a fraudulent rendering of a future that will not come to pass, used instead as a weapon to eliminate those deemed incompatible with the absurdity of continued orientation around market- and growth-driven expectations in a nation where a shrinking, aging population has been the reality for decades. My position is that broad recognition of alternatives is inherently necessary. What form those alternatives take, and how fundamentally they orient toward empathetic dignity as a defining characteristic, are what we await. Japan offers an illustrative point of beginning for such an endeavor.

Financial support

This research was supported by a Fulbright Scholars Program research award for Japan.

Competing interests

The author reports no competing interests or conflicts.

Author biography

Paul Christensen is Associate Professor of anthropology at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana. He is the author of many works on Japan’s approach and framing of alcoholism and addiction recovery, including Japan, Alcoholism and Masculinity: Suffering Sobriety in Tokyo (Lexington 2014). He can be reached at christen@rose-hulman.edu.