Early tar production in Sweden: techniques and evolution

Tar is obtained from wood that is heated in a low-oxygen environment. While tar can be extracted from most types of wood, the most common source in Scandinavia is pine, with birch bark used occasionally for special purposes (Persson Reference Persson1994). Tar (and its derivative: pitch) has been used for many purposes, including in leatherworking, lubrication, corrosion protection, flavouring and medical treatments. By far the most common use, however, has been in the treatment, protection and sealing of wooden constructions (Persson Reference Persson1994: 1–2). Various resinous substances were employed far back into Scandinavian prehistory, with the earliest examples of birch resin mixed with beeswax being used as glue or sealants from the Mesolithic onwards (c. 8000–4000 BC) (Heron et al. Reference Heron, Evershed, Chapman and Pollard1991: 325, 329–30).

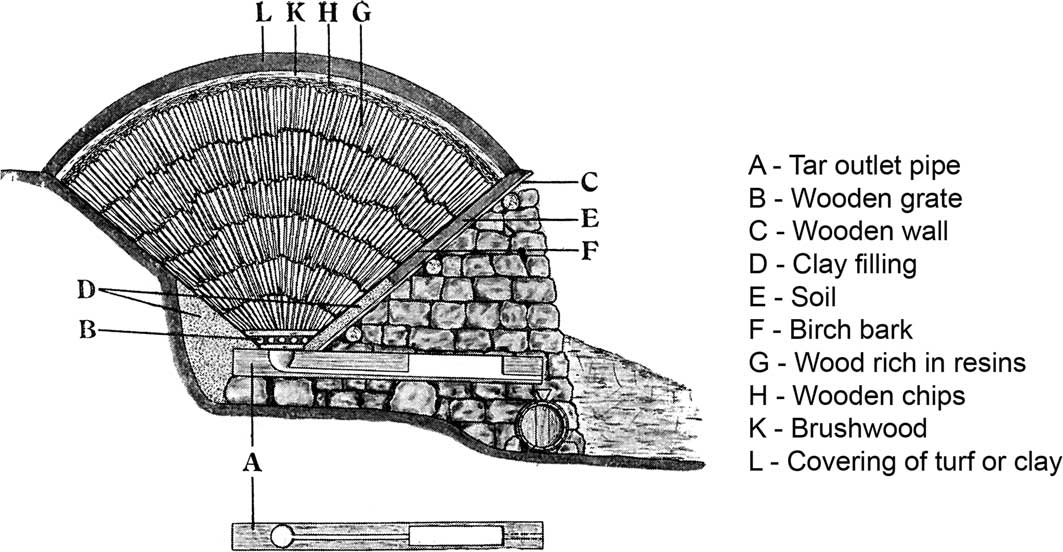

In the early modern period, tar was one of the most important export products from Sweden (which included Finland and was part of Sweden until 1809). It was produced in huge amounts using tar kilns or tar dales—cone-shaped pits dug into a natural hill slope (Figure 1). Wood was stacked in the upper part, set alight and covered with turf and charcoal to control the availability of oxygen; heat from the combustion caused the tar to condense out of the wood and drip down inside the kiln. An outlet pipe at the base enabled the separation of the various tar fractions during different phases of the production cycle, and their collection in barrels, while the wood was still burning. Finnish historical sources state that such outlet pipes were introduced in the late medieval period, thus improving safety and efficiency over previous methods and making it possible to produce higher-quality tar (Villstrand Reference Villstrand1996: 62).

Figure 1 Schematic section of a tar kiln with a tar outlet pipe in the bottom, used in Scandinavia in historical times (letters I and J are not used) (translation from Bergström Reference Bergström1941: part II, p. 57).

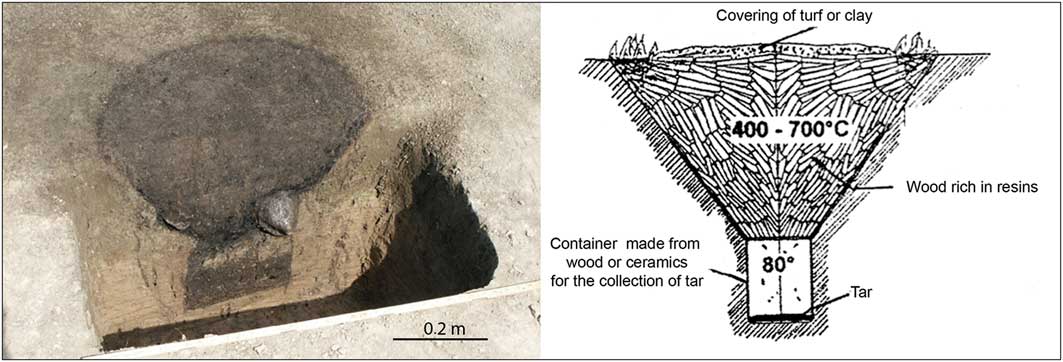

Until recently, little attention had been paid to prehistoric tar-production methods. In the early 2000s, in the Uppland province of eastern-central Sweden, however, archaeological excavations at settlements in the open fields around Uppsala, in advance of new motorway construction, revealed a series of funnel-shaped pit features (Figure 2). Through analogy with similar discoveries from Central Europe, along with wood-anatomy analysis and geochemical analysis using GC-MS, these features can be linked to the production of tar from pine. Their form suggests the use of a method of production similar to historical tar kilns, although these pits lacked the outlet pipe; the tar instead accumulated in a container at the base of the pit. After burning, the upper section had to be demolished so that the tar could be extracted from the underlying space. The surviving parts of these features are approximately one metre in diameter, and the estimated amount of tar produced per firing would rarely have exceeded 15 litres. Thirty-eight radiocarbon dates retrieved from the pit features indicate that they are contemporaneous with the prehistoric settlements in which they are found. Most date from the Roman Iron Age (AD 100–400), with some later examples (Berggren & Hennius Reference Berggren and Hennius2004; Hennius et al. Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005; Hjulström et al. Reference Hjulström, Isaksson and Hennius2006; Hennius Reference Hennius2007: 597; Svensson Reference Svensson2007: 615; Svensson-Hennius Reference Svensson-Hennius2017).

Figure 2 Funnel-shaped feature used for tar production in the Roman Iron Age (photograph courtesy of Upplandsmuseet) and a schematic reconstruction drawing (amended from Kurzweil & Todtenhaupt Reference Kurzweil and Todtenhaupt1998).

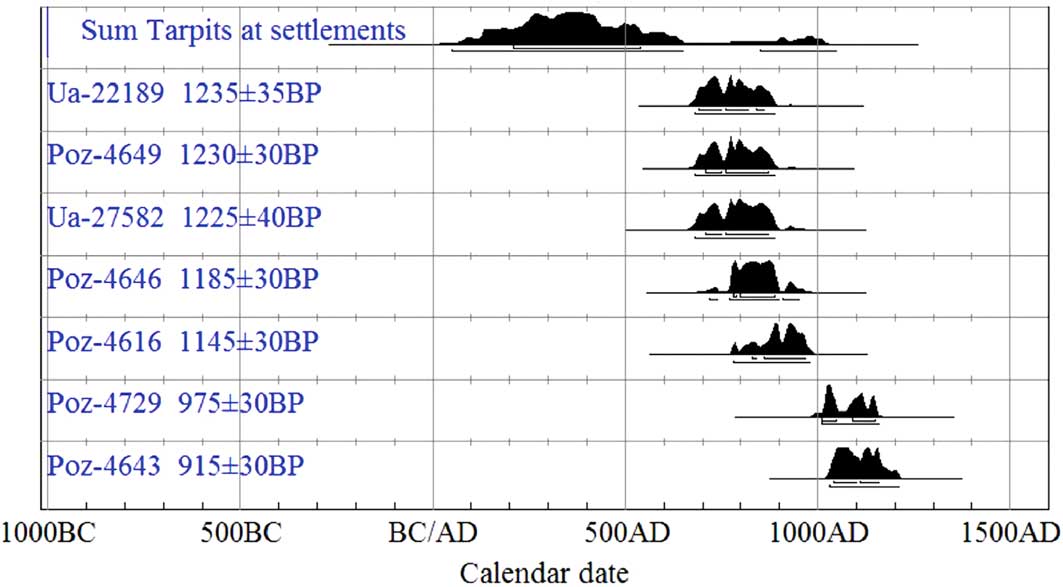

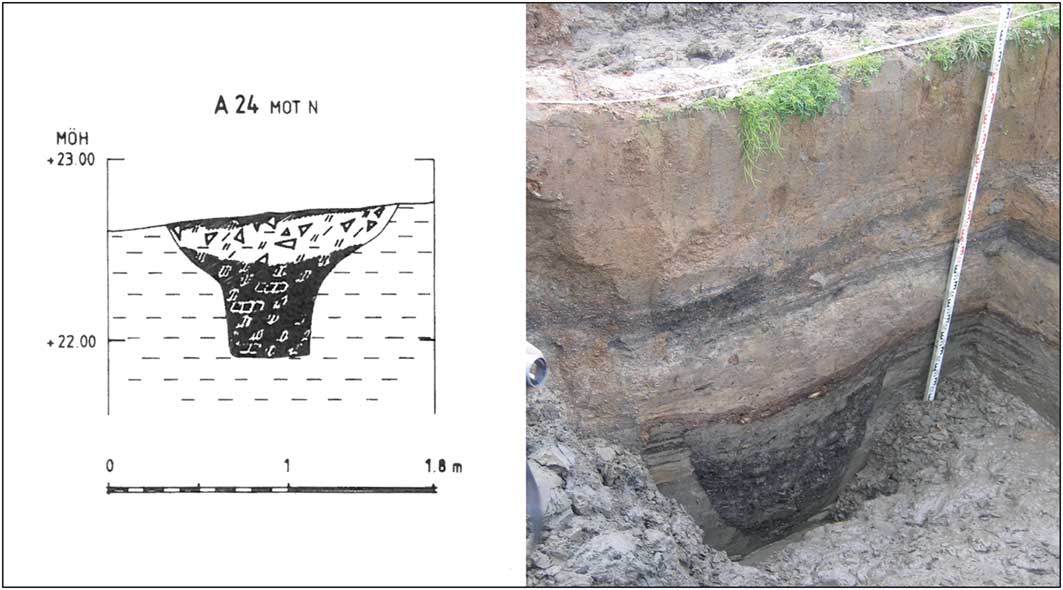

More tar-production pits were excavated in the forested northern parts of the province, during the same road-construction project. These pits are similar to those found at the settlement sites to the south, with enclosed compartments in the bottom and lacking channels for the continuous drawing of tar. They are, however, up to 10 times larger, and it is estimated that at least 200–300 litres of tar could have been produced per burning episode (Figure 3; Hennius et al. Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005; Hjulström et al. Reference Hjulström, Isaksson and Hennius2006: 292). So far, the seven radiocarbon dates obtained for this second group of pit features suggest that the large-scale production of tar was perhaps already underway in the eighth century AD. Calibrated dates from the three oldest features give a date range of AD 680–900 (at 95.4% confidence; Figure 4). Several factors must be considered when relying on radiocarbon analysis for dating tar-production features. For large pits that were used repeatedly and that yield an abundance of charcoal, sample context is crucial. To date the features accurately, samples were preferably collected from accumulations of charcoal in the lower part of the feature. The use of old wood is well attested into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Microstructural analysis of wood from the tar pits, however, shows the use of 30–40-year-old trunks, with no evidence of insect activity, as would be expected in dead or rotten wood. Both factors indicate the use of fresh wood, which was probably prepared for several years before felling by making cut marks in the bark. This would have promoted an increase in resin production, and thus a greater tar yield upon burning. One of the features was also dated using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), giving a result consistent with the radiocarbon analysis (Andersson Reference Andersson2005: 26; Hennius et al. Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005: 39; Björck Reference Björck2008: 107).

Figure 3 One of the large tar-production pits from a forested area to the north of Uppsala, and the section drawing from the excavation (photograph courtesy of Upplandsmuseet; drawing by Hennius et al. (Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005: 21))

Figure 4 Summarised calibration diagram from 38 tar-production pits excavated at settlement sites (above), and the seven dated tar-production pits from the forests below (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Baillie, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Bertrand, Blackwell, Buck, Burr, Cutler, Damon, Edwards, Fairbanks, Friedrich, Guilderson, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, McCormac, Manning, Bronk Ramsey, Reimer, Remmele, Southon, Stuiver, Talamo, Taylor, van der Plicht and Weyhenmeyer2004; Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; unpublished compilation by Svensson-Hennius Reference Svensson-Hennius2017).

The excavation of the large tar-production pits in the forested region identified no nearby associated archaeological features, such as settlements or graves. These large-scale production sites seem, instead, to have been located up to 8km from the nearest contemporaneous settlements, identified through burials or structural remains (Hennius et al. Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005: 39, 43; Hennius Reference Hennius2007: 598, 607–609; Hennius Reference Hennius2016). So far, geographic distribution of these tar-production pits is limited, with a large concentration of at least 125 features to the north of Uppsala, along with a few examples from Norway and Åland (Fredman Reference Fredman2009: 16; Svensson-Hennius Reference Svensson-Hennius2017). There are almost certainly further, as yet undiscovered, tar-production sites in other parts of Scandinavia; many features visible on the ground’s surface, and previously interpreted and registered as animal trapping pits or charcoal pits, are similar in form to tar-production sites and may have been misidentified.

The change in the location and construction of the larger pits seems to signify a shift towards large-scale tar production in the eighth century AD. While it was possible to produce large amounts of tar by repeated firings in the small pits located in the settlements, the eighth-century change in production location implies an important shift in the mode of production and the organisation of labour associated with the larger pits. These were now strategically located nearer the forested areas, and hence closer to the source of the raw materials. The size of the pits would have also required the planning of wood supply on a larger scale than that needed to fire a small tar pit in a settlement. Building, operating and maintaining the larger pits in the forest would have required considerable and time-consuming work: forest management, cutting trees, chipping and stacking wood, and monitoring the firing. Furthermore, a supply of barrels would have been required for transporting several hundred litres of tar after each production cycle.

Small-scale tar production at settlement sites persisted into the Late Iron Age (c. AD 550–1050, divided into the Vendel Period 550–750 and the Viking Age 750–1050). The tar was probably used during the construction of houses, or for other household activities. Reorganisation to support large-scale outland production external to the settlements therefore suggests an increased demand for tar in other sectors of society. Here, I propose that this increase was synchronous with developments in Viking Age shipbuilding and maritime expansion, and dependent on a reorganisation of land-use, resulting in intensive use of the outlands.

The need for tar in shipping

The change from small- to large-scale production of tar coincides with an intensified maritime focus, including new shipbuilding techniques, the introduction of the sail and the beginning of far-reaching expeditions across the Baltic (Larsson Reference Larsson2007: 83, 85, 92–95, 114; Bender Jörgensen Reference Bender Jörgensen2012: 173; Peets et al. Reference Peets, Allmäe, Maldre, Saage, Tomek and Lõugas2012: 15; Konsa Reference Konsa2013: 152; Price et al. Reference Price, Peets, Allmäe, Maldre and Oras2016: 1022; Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 31, 100). As in historical times, the need for tar to support Viking Age maritime activities was probably extensive. Based on experiments, Ravn (Reference Ravn2016) has estimated the amount of tar required for the construction of a large ‘personnel carrier’ at approximately 500 litres. This quantity of tar would require approximately 18m3 of wood, and some 1600 working hours to produce. The Viking fleets mentioned in written sources sometimes included hundreds of ships (Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 31, 70, 100).

There is archaeological evidence for the use of tar in the Late Iron Age, even if conservation processes complicate analyses. The Vendel Period boat from Sutton Hoo in south-east England, for example, featured not only tarred caulking, but also a bucket of tar mixed with sawdust placed in the central grave chamber (Bruce-Mitford Reference Bruce-Mitford1975: 341, 456, 486). There are several Scandinavian examples of planks, wooden nails and caulking treated with tar—sometimes mixed with yellow ochre and fatty substances—that might represent the ‘seal tar’ mentioned in the Saga of Erik the Red (Brøgger & Shetelig Reference Brøgger and Shetelig1951: 116; Arbman Reference Arbman1993: 31; Egenberg Reference Egenberg2003: 63, Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 32). Although tar may also have been used for treating ropes in ship rigging, there seems to have been a preference for making ropes from lime or linden bast fibres for Danish Viking Age boats at least, with no archaeological traces of tar treatment in evidence. Tar was probably not required here, as lime bast ropes become stronger when wet (Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 50). The situation is different for Norway, however, where several examples of tar-treated hemp ropes have been found (Hiorth Reference Hiorth1908: 18–23).

Large quantities of tar were probably used for treating sails. Experiments show that woollen sails perform better than other materials, as they provide more elasticity in strong winds. Woollen sails, however, are highly permeable and require a sealing coat, or smörring, to be applied to their front side (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Christiansen and Hammarlund2002: 207; Larsson Reference Larsson2007: 93). Archaeological sail fragments and historical and ethnological sources show that different mixtures of fat, grease, tar or other resinous substances, as well as ochre, were used (Andersson Reference Andersson1995: 255; Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Christiansen and Hammarlund2002: 205; Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 47). In experiments, tar comprises only a few per cent of the coating mixture, but for the large Viking Age ships, the size of the sails was around 100m2. The total area of the sails of the Danish-Norwegian Late Viking Age fleet is estimated at approximately one million square metres (Bender Jørgensen 2012: 179; Hvid & Ravn Reference Hvid and Ravn2016: 182). This substantial area (also including Swedish ships) suggests that a considerable amount of tar was needed for sail coating.

The coating on boats and sails also required continuous maintenance, which will have driven a constant demand for tar. Tar-production features in contexts that indicate such continuous use have been found at sites associated with boat maintenance. One example, excavated in the late 1980s, is Herrebro in Sweden. At the time of excavation, the link between tar production and funnel-shaped pits had not yet been established. Such a reinterpretation of the Hererbo features, however, seems highly plausible, based on stratigraphic profile drawings. One of the two pits was radiocarbon dated to the ninth or tenth century AD (Figure 5; Lindeblad et al. Reference Lindeblad, Hedvall and Nielsen1994: 48–49, 57). Other examples are found among Viking remains beside Russian rivers. So far, the oldest tar-production feature discovered here is at the port site of Gnezdovo by the Dnieper River, which yielded two tenth-century funnel-shaped tar pits associated with evidence for the loading, unloading and maintenance of Viking ships (Figure 5; Fetisov & Muraševa Reference Fetisov and Muraševa2008). Another example comes from Vyplozov on the Desna River in the Ukraine, where excavations have revealed ceramic fragments with traces of tar from ditches interpreted as landing spots for Viking Age ships (A.A. Fetisov pers. comm.).

Figure 5 Tar pit excavated in Herrebro (reinterpreted) from Lindeblad et al. (Reference Lindeblad, Hedvall and Nielsen1994) and tenth-century tar pit from the Gnezdovo site, Smolensk region. (Excavations by V.V. Murasheva, State Historical Museum, 2006–2007; photograph by A.A. Fetisov, State Museum of Oriental Art.)

As stated above, several different sources provide evidence for the use of tar within shipping, and the size of the Late Viking Age fleets suggests an extensive and continuous need for the product. The increasing need for tar entails changes in the transportation and organisation of labour, and makes it more probable that a commodities trade in tar was initiated, connecting the forested outlands with inter-regional trade networks.

Tar as a trade commodity

The identification of archaeological organic substances as trading commodities is challenging. When tar is discussed from this perspective, one must also consider the natural landscape and the availability of sufficient coniferous wood for tar production. The long-distance transportation of timber is generally considered to have begun in the thirteenth century AD (Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 91), although evidence from several Scandinavian Viking Age trading centres suggests a much earlier trade in refined wood tar. Ceramics from the Swedish emporia of Birka, for example, show traces of tar, which Frostne (Reference Frostne2002: 22) interprets as evidence for tar collection, storage or processing. Underwater excavations in the harbour basin have yielded a tar brush and a birch-bark vessel containing tar (Stahre Reference Stahre2012; Lindström Reference Lindström2014).

Ribe in Denmark provides evidence for long-distance tar trading earlier than the Viking Age. A well excavated on the site incorporated a reinforced lining in the form of a barrel, the interior of which preserved thick layers of tar made from either pine, spruce or larch. Dendrochronological analysis shows that this barrel came from Nieder Sachsen (modern Lower Saxony in north-west Germany), and dates to the early eighth century AD. The tar was probably produced around the Harz area (northern Germany), and was transported to Ribe via the River Elbe (Bencard et al. Reference Bencard, Bender Jörgensen and Brinch Madsen1990: 59–60, 145). Further evidence for tar use has been found in the harbour basin of the Viking Age town of Hedeby/Haithabu, which yielded over 90 brushes used for the application of tar (Ravn Reference Ravn2016: 31). Kalmring (Reference Kalmring2010: 370–71) reports on finds from Schleswig, where several wooden troughs, made from split logs of pine and used for the transportation of tar, have been discovered. As local coniferous wood was scarce, it is suggested that the tar was brought from the Duchy of Lauenburg, the southern Baltic coast areas, Sweden or Finland.

Discussion

Based on the evidence presented above, I suggest that tar production in eastern Sweden developed from a small-scale household activity in the Roman Iron Age to large-scale production that relocated to the forested outlands during the Vendel/Viking Period. This change, I propose, resulted from the increasing demand for tar driven by an evolving maritime culture. This shift in production was also paralleled by similar changes in the refinement of other commodities. The beginning of the Late Iron Age, for example, saw an expansion of activities external to settlements, and colonisation of marginally used areas, such as forests, coastal areas and mountains. There was also a concurrent increase in the exploitation of non-agrarian resources, evidenced by hunting, fishing and iron production (Magnusson Reference Magnusson1986: 221–22; Landin & Rönnby Reference Landin and Rönnby2002; Lindholm & Ljungkvist Reference Lindholm and Ljungkvist2015: 18–19). In relation to this wider picture, the following discussion considers the social organisation of tar production and the local and regional circulation of tar products.

Prehistoric tar production could have been organised in many different ways, in a multitude of combinations, possibly under the control of political or economic elites. Tar production could have been conducted by individual, free farmers, or cooperatively by organised groups of farmers. It could also have been a strategy used by other groups of people who found new income from exploiting non-agrarian forest products. Scandinavian Late Iron Age society was also a slave-based economy (Brink Reference Brink2012: 259, 262). In the Old Norse poem Rígsþula, for example, the thralls (serfs or slaves) are said to have performed heavy work, such as building stone fences and digging for peat (Brink Reference Brink2012: 169–71). According to Swedish medieval laws, male slaves shepherded grazing animals, in addition to undertaking woodland labour and fishing (Nevéus Reference Nevéus1974: 68, 87, 113, 139).

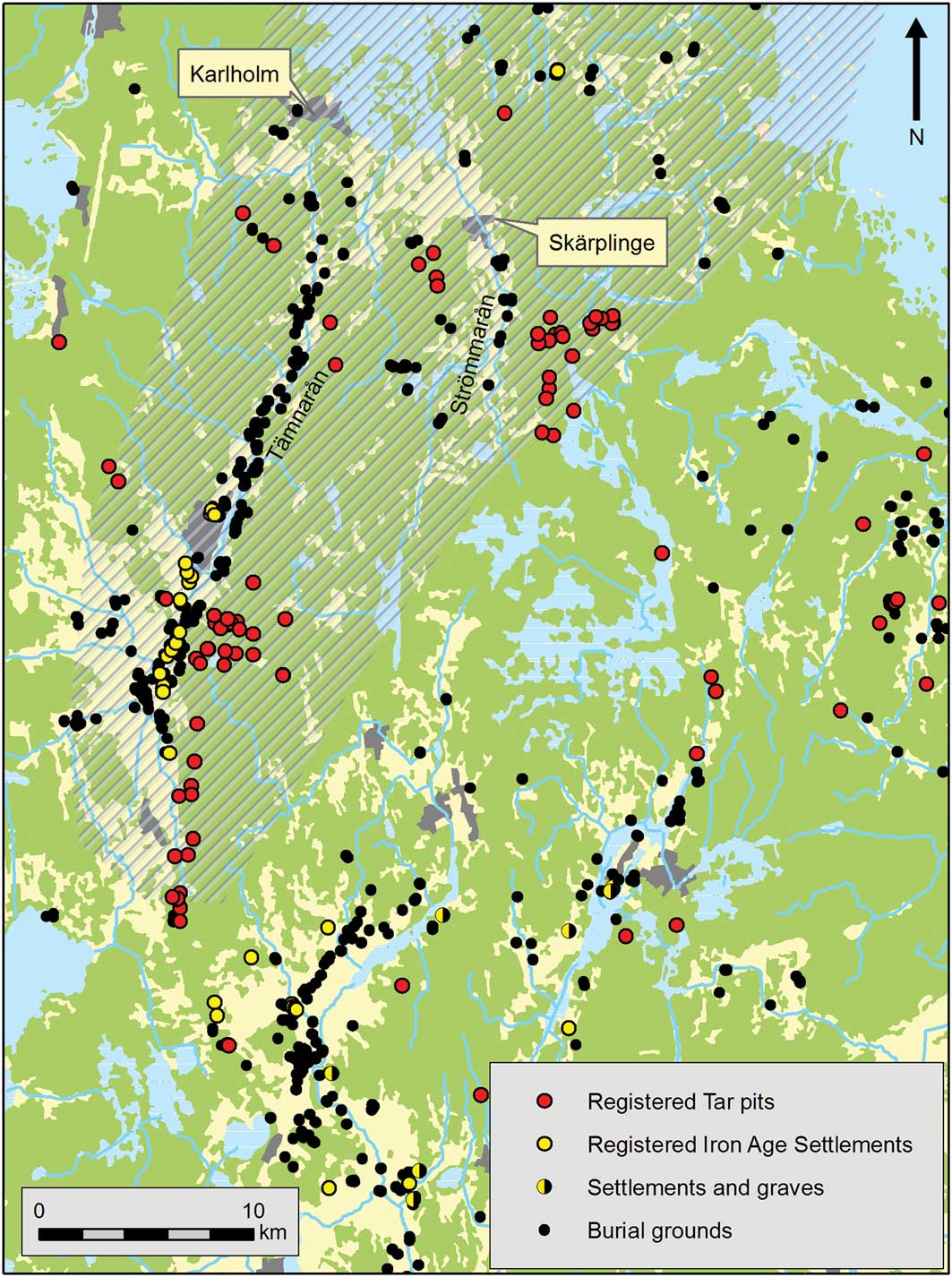

The lack of graves or settlement evidence close to the forest tar pits, however, may suggest that tar production was managed from the agrarian-based settlements located in the river valleys (Figure 6). Historical accounts and maps of the forest areas containing tar pits show a correlation between the tar-production sites and historically known shielings (in Swedish, Fäbod or Säter—seasonally used occupation areas away from the home farm, and often associated with transhumance and grazing animals, but also other types of activities) (Hennius et al. Reference Hennius, Svensson, Ölund and Göthberg2005: 43). We know from both Norway and Iceland that the shielings were part of the Viking Age agricultural system, and were typically situated about 2km from the home farm, with some examples up to 15km away (Skrede Reference Skrede2005: 40; Kupiec & Milek Reference Kupiec and Milek2015: 108). Sindbæk (Reference Sindbæk2011: 103, 108) proposed that outland shielings were important for surplus production and wealth in Viking Age Denmark. The economic focus was on animal grazing, but it was also combined with a wide range of other resources. The tar-production sites were often placed close to low-lying areas suitable for haymaking and grazing, and could be viewed as integrated within a shieling system, where seasonal tar production was combined with other activities on task-specific sites away from the ordinary settlements. This represents a transition from the Early Iron Age widespread grazing system (Petersson Reference Petersson2006: 262–63) to one of seasonally based camps, which later evolved into the historically documented shielings. The pattern of outland use, based on a field-and-meadow system, seems to have been established in several places during the Late Iron Age (Karlsson & Emanuelsson Reference Karlsson and Emanuelsson2002: 124–27; Emanuelsson et al. Reference Emanuelsson, Johansson, Nilsson, Pettersson and Svensson2003: 130). This spatial organisation would imply that people were released from agrarian work to spend time in the forest on the production of tar, and perhaps other activities. Such specialisation could also make use of spare farm labour during quieter periods within the agricultural cycle. In historical times, tar production was conducted by farmers, and could easily be integrated with the agricultural calendar (Villstrand Reference Villstrand1996: 69–72).

Figure 6 Map showing the northern part of the province of Uppland, where the great majority of tar-production pits are registered. A concentration along waterways is clearly evident. Hatched area corresponds to archaeological region 40a, according to Hyenstrand (Reference Hyenstrand1984).

A by-product of tar production is charcoal. The process of manufacturing charcoal is similar to that for tar—burning wood in a low-oxygen environment. The quantity of charcoal found in association with the tar pits, however, is surprisingly low, given the volumes of wood used in tar production. It is possible that the charcoal was used in iron-production, an activity that needed large volumes of fuel, and thus further increased the profit from tar production. Few iron-production sites contemporaneous with the tar-production features, however, have been identified in the area.

The presence of barrels, buckets, brushes and troughs in Viking Age emporia indicates the importation and use of tar. The connection between the tar-production areas in the forests of northern Uppland and the market, however, is unknown. The production area is dominated by the Rivers Tämnarån and Strömmarån, which run northwards to the Baltic Sea (Figure 6). Based on the specific characteristics of its ancient remains, the area has been characterised as its own region (region 40a, Hyenstrand Reference Hyenstrand1984: 189), separate from the southern parts of Sweden. Few archaeological excavations have been conducted in Karlholm and Skärplinge, where the two rivers discharge. The Swedish Archaeological Sites and Monuments database as well as artefacts deposited at the Swedish History Museum (FMIS Västland 102/SHM 23115 resp. FMIS Österlövsta 206:1/SHM 26335; www.fmis.raa.se), however, record evidence of Viking Age wealth and trade at both places, including swords, balance scales and jewellery. In late fourteenth-century historical accounts, Skärplinge is documented as one of many smaller marketplaces along the Baltic coast, trading in grain, fish, meat and butter, and probably also down feather and seal blubber (Broberg Reference Broberg1990: 116–17). Trade was very probably already initiated at these coastal sites in the Viking Age, where tar could be loaded for onward transport within inter-regional trade networks.

Conclusions

Recent archaeological excavations have cemented the link between previously poorly understood funnel-shaped features and the production of tar. It has also been possible to trace the development from small-scale, settlement-based household tar production to large-scale production in the forested outlands, immediately prior to the Viking Age. This development coincides with Scandinavian society’s intensified marine focus and the introduction of the sail. This most probably drove the increase in tar production, which was used for protecting wood, impregnating and sealing sails, and as a trade product. Tar production may have been combined with other seasonal activities in a shieling-like system controlled from the settlements in the agrarian river valleys. The tar was transported by river to smaller marketplaces on the Baltic coast and, from here, onwards to emporia. The forested outlands, therefore, played an integral part in the larger inter-regional networks.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Berit Wallenberg Foundation (grant BWS2014.0117) for funding this work, together with the ‘Viking Phenomenon’ project from the Swedish Research Council (grant 2015-00466). I also thank Jonas Svensson-Hennius for sharing the compilation of 14C-datings, Calum McDonald for language revision and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.