Article contents

Migrations or local interactions? Spheres of interaction in third-millennium BC Central Europe

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 September 2020

Abstract

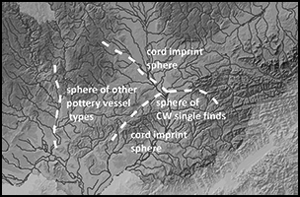

Increasing scholarly interest in past human mobility has provoked intense debate between archaeologists and archaeogeneticists. Explanations advanced by the latter have been criticised for framing explanations in terms of large-scale migrations, lacking underpinning social theory or interest in human behaviour; conversely, archaeologists have been criticised for supplying samples but no intellectual input. This article uses examples of ceramics and chipped stone tools to illustrate local interactions within regional Eneolithic Corded Ware culture in Moravia, demonstrating that what may appear as a homogeneous archaeological culture spread by mass migration can be understood as a more complex series of overlapping, local cultural changes.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2020

References

A correction has been issued for this article:

- 4

- Cited by

Linked content

Please note a has been issued for this article.