Introduction

Global research on population aggregation over the past few decades has documented an impressive diversity in organisation, structure, density and mechanisms of growth. Such work highlights numerous settlements that defy—or expand—traditional expectations about the characteristics of cities and other large settlements. Examples include research on low-density urbanism (Fletcher Reference Fletcher2019), implanted urbanism (in which urban forms are imposed on non-urban societies, see Bemmann et al. Reference Bemmann, Linzen, Reichert and Munkhbayar2021) and mega-sites without obvious hierarchical structure or social segmentation (e.g Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman, Gaydarska, Fernández-Götz and Krausse2016). Consequently, there has been a theoretical reconsideration of urban definitions, emphasising the effect of cities on their hinterlands and their amplifying effects on social interaction, driven by the density and frequency of human interactions that they promote (cf. ‘energized crowding’ in Smith Reference Smith2023). Crucially, the investigation of large non-urban settlements is an important component of wider investigation of urbanism as a phenomenon.

In the South Caucasus, when scholarship has engaged with this global urbanism discourse, perspectives have mostly coalesced around a model of non-urban social complexity involving fortress-settlements. These sites, which are characterised by defensive walls and/or ditches and often employ defensible natural features (e.g. hilltops and gorges), emerge c. 1500 BC and likely influence the form and structure of large first millennium BC Urartian and Hellenistic settlements in the region (Stone Reference Stone, Marcus and Sabloff2008; Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013; Fabian Reference Fabian and von Reden2023; Earley-Spadoni Reference Earley-Spadoniin press). Urartian texts reference “royal cities” in the area (Melikishvili Reference Melikishvili, Pigulevskaya, Kallistov, Katsnelson and Korostovtsev1962: 322), but these seem to be either intentional exaggerations or modern mis-readings of an ancient terminology that does not map well onto modern categorisations (Earley-Spadoni Reference Earley-Spadoniin press). Still, some have argued that—given the lack of systematic investigation of lower settlements and ‘near hinterlands’—there is still considerable latitude for exploring whether fortress-settlements may have had attributes and/or functions associated with cities elsewhere (Hammer Reference Hammer2014). Given recent trends exploring diversity in urban forms and in large non-urban settlements, it is worth investigating how large South Caucasus fortress-settlements fit into this broader spectrum. For example, the possible role of pastoralists and inter-communal conflict in driving population aggregation and social complexity in the South Caucasus (Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019) may be useful in contextualising potentially analogous processes elsewhere in Eurasia (Anthony Reference Anthony, Hanks and Lindruff2009; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Betts, Doumani Dupuy, Cong and Jia2018).

Archaeological survey (via remote-sensing, aerial and terrestrial methods) has identified a few large fortress complexes (tens to hundreds of hectares) that may date to the Late Bronze or Iron Age (c. 1500–500 BC) (Badaljan et al. Reference Badaljan, Edens, Kohl and Tonikjan1992; Hammer Reference Hammer2014), but further work is necessary to define this phenomenon. Consequently, South Caucasus mega-fortresses remain poorly understood as a settlement type, even with respect to basic questions of size, structure and layout.

Various factors have hindered efforts to understand South Caucasus fortresses and their settlements. While the origins of a fortress-based model of population aggregation can be traced back decades (Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019: 414), systematic surveys—deploying a range of aerial and ground-based techniques—have been employed to investigate these models only in the past 20 years (Lindsay et al. Reference Lindsay, Smith and Badalyan2010; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Cleary, Birkett-Rees, Krsmanovic and Tskvitinidze2018; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019; Herrmann & Hammer Reference Herrmann and Hammer2019). Many of the widely varying ecological and topographic environments of the Caucasus (unploughed, turf-covered pasturelands, subtropical marshlands, temperate forests) are challenging for archaeological survey. Site formation processes favouring lateral movement (horizontal stratigraphy) rather than vertical tell-building also pose interpretive difficulties.

The survey of Dmanisis Gora, a 60–80ha fortress-settlement of exceptional preservation and size, offers an unprecedented opportunity to investigate the spatial organisation of one of these large sites. In regional terms, these results bring wider discussions of mega-sites into focus for the South Caucasus. From a broader geographic perspective, they contribute to comparative analyses of diversity in the forms of large settlements and offer insights into the factors driving population aggregation, particularly in mountainous regions and in areas dominated by pastoralism.

Late Bronze and Iron Age landscapes in the Lesser Caucasus borderlands

The Late Bronze and Iron Age settlement landscape of the South Caucasus is characterised by an expansion in the number of settlements and fortresses, marking a return to more substantial built environments following the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2400–1500 BC), when settlements were rarer. The social organisation and spatial structure of these communities, their relationship with more mobile segments of society and the existence of ‘lower settlements’ below the main fortress have been discussed extensively (Hammer Reference Hammer2014; Lindsay et al. Reference Lindsay, Leon, Smith and Wiktorowicz2014; Chazin et al. Reference Chazin, Gordon and Knudson2019; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019). Tantalisingly, where research strategies and archaeological preservation have permitted, ‘halos’ of settlement (and cemeteries) have been documented around fortresses, as well as long segments of fortification walls that extend between or around fortresses.

Prior fieldwork in southern Georgia, carried out as part of the project Archaeological Research in Kvemo Kartli (Project ARKK), has documented a rich landscape of Late Bronze and Iron Age fortress settlements. These include sites with evidence of metal production (Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kakhiani and Newman2020) or occupation beyond the fortified hilltop (Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019).

The fortress of Dmanisis Gora (Figure 1) consists of a double-walled fortress core and a much larger outer enclosure with additional fortifications. Two steep-sided gorges, with a depth of 60m in places, supplement the defensive walls. Prior research noted that the site had an unusually large outer walled enclosure, but the site was not systematically mapped (Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili2019; Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022). Small-scale excavations in the inner fortress in 2018 identified stratified architectural remains in two main phases. Radiocarbon dates for the earlier phase gave results in the twelfth or eleventh centuries BC, while a charred seed from a ceramic vessel in a burial gave a date in the tenth century BC. Ceramic evidence points to an Iron Age date, probably in the first half of the first millennium BC, for the later phase (Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022). The large ceramic assemblage (more than 30 000 sherds in the 2023 season alone) overwhelmingly dates to the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, but with some evidence for both earlier (Early Bronze Age) and later activity (tentatively Classical to Late Antique/Early Medieval). Low levels of post-Iron Age pottery in the upper layers are not unexpected, as the large cyclopean defensive walls would have had continued appeal as a periodic refuge. The quantity of ceramics, depth of stratification and presence of pig remains suggest year-round occupation in the inner fortress.

Figure 1. Map of the Dmanisi plateau and surrounding areas. Former extent of field systems estimated from Corona satellite imagery (mission 1115-2, frames: 91–92, date: 20 September 1971). Elevation data: Shuttle Radar Tomography Mission (figure by R. Higham & N. Erb-Satullo).

Survey methods

Site formation processes and architectural preservation at Dmanisis Gora are ideally suited for aerial survey. Shallow sedimentation in the outer enclosure means that features are visible on the surface. Survey was undertaken in early autumn when grass cover was minimal.

A DJI Phantom 4 RTK unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was used to map the entire site and adjacent areas (total: 115ha). An RTK base station provided relative positioning accuracy of 20mm or better. Orthophotos, digital elevation models and hillshades were produced via photogrammetry from nearly 11 000 aerial photographs in Agisoft Metashape. Orthophoto resolution was approximately 1cm/px; digital elevation models were downsampled to 3.4cm/px to capture subtle variations in underlying topography more effectively. Ground control points shot with a total station were used to refine georeferencing.

Features observed in orthophotos and hillshades were investigated through ground-level observation, and geospatial datasets were adjusted accordingly. While time-intensive, the combination of aerial and systematic ground-based observation was necessary for distinguishing natural features, such as exposed bedrock, from anthropogenic ones. In a small minority of cases, there was ambiguity, even after ground-truthing, in whether a feature was anthropogenic or not. Uncertain or otherwise ambiguous features were noted in the geodatabase, but as these were relatively rare, it did not affect interpretations of overall site structure.

Unlike at lowland sites previously investigated by Project ARKK (Erb-Satullo Reference Erb-Satullo, Anderson, Hopper and Robinson2018; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019), systematic surface collection of artefacts was not effective for mapping occupation in space and time. Sites in highland pasture have notoriously scant surface assemblages (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Badalyan and Avetisyan2009: 102). In the two weeks spent ground-truthing features, only a few small, undiagnostic pieces of ceramic and obsidian debitage were noted in the outer enclosure; systematic surface collection was therefore not attempted.

Lastly, to contextualise Dmanisis Gora within its wider settlement landscape, we undertook a wider survey of the surrounding areas, targeting fortresses and settlements (Figure 1). While these data are not presented in full here, we refer to some of these results where relevant (e.g. in reference to fortress-hinterland dynamics).

Results

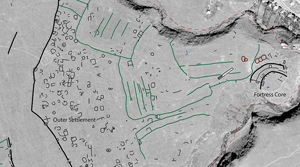

Aerial survey and ground-truthing mapped hundreds of anthropogenic features across the site, including fortification walls, rectilinear and curvilinear stone features, probable mortuary structures and field systems (Figure 2; for raw data see Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Higham, Weber-Boer, Symons and Portes2024). Nearly all the features beyond the inner fortress were previously unmapped (cf. Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022: fig. 8).

Figure 2. Map of Dmanisis Gora highlighting archaeological features. Red dotted line indicates extent of UAV photogrammetry. Background image is a Hexagon satellite image (mission: 1210-3, frame: 58, date: 31 August 1975) (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Fortress core

The inner fortress (approximately 1.5ha) consists of two substantial fortification walls, with a third wall running parallel between them (Figure 3). The latter has a more muted topographic expression than the larger fortification walls and is probably not a major defensive barrier. Within the innermost defensive wall, where excavations documented late second and first millennia BC occupation, it is difficult to distinguish walls from areas of collapse without excavation. Nevertheless, walls built perpendicular to the inner fortification wall attest to the presence of buildings along its interior aspect. In addition, a series of long low linear mounds are visible in the inner enclosure, oriented north-west to south-east. At least three are present: two running parallel to one another, and a third at a slight angle to the others. Excavations in trench 2—positioned on one of these mounds—in 2018 (see Figure 3) suggest these are a linear arrangement of buildings belonging to the upper second phase.

Figure 3. Hillshade (top left) and orthophoto (top right) of fortress core, with plan of trench 2 excavations. For full details of excavations, see Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani (Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022) (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

The space between the two major defensive walls of the inner fortress is filled with stones that are larger and more numerous than those in the innermost compound (see hillshade and orthophoto in Figure 3). Nevertheless, several linear stone features were noted, some of which appear to have been built against the outer side of the inner defensive wall. Excavations in trenches 1 and 3 tentatively support this observation (Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022: fig. 10). Some stone alignments, potentially terraced buildings, were also identified directly to the north of the inner fortress.

Mounded features were noted on both sides of a field boundary to the north-east of the inner fortress. These are possibly kurgans, but they differ morphologically from other, more definitive burials in the outer settlement (see below). Moreover, their proximity to the field boundary and a long rectangular barn foundation (Figure 2) raises the possibility that they are associated with recent agricultural activities.

Fortification walls

Comprehensive aerial survey of the outer enclosure documented a 1km-long fortification wall running from gorge edge to gorge edge (Figures 2 & 4). In its central and southern sections, it runs along a slight rise (approximately 2–6m elevation difference), with lower ground to the west, consistent with a defensive intent. This is one of the few places on the site where the general trend of increasing elevation from east to west is reversed. Fortification walls are easily distinguished from field boundary walls (Figure 5). The width of the fortification wall collapse is about 4–5m, and in one or two places preserved facing stones suggest an original width of about 2–2.5m. Field boundary walls are narrower, typically consist of a single line of stones less than 1m across and enclose rectilinear fields with evidence of ploughing.

Figure 5. Comparison of fortification walls (A–C) with field boundary walls (D–F) using hillshade (A & D) and orthophotos (B & C, E & F) (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Outside the complete 1km fortification wall are three partial sections of additional walls (Figure 2). Two of these align and may once have formed a perimeter wall that was either partially destroyed or never completed. The third section is less well preserved but has features more characteristic of a fortification wall than a field boundary. The total area of plateau defended by these outer walls is about 80ha, though the settlement is mostly contained with the smaller area defined by the complete 1km fortification wall.

Stone structures are directly associated with the outer fortification walls, particularly the 1km complete wall and the southernmost partial wall section. These include both rectilinear and curvilinear features, some of which appear to be built against the wall. Interpretation of these structures and their relationships to the fortification was challenging from surface observation alone. Circular or semicircular features, especially those filled with stones, might be interpreted as buttresses or watchtowers, particularly where adjacent gaps in the wall might indicate the presence of gates. Others, however, are similar to cromlechs (stone tombs) seen elsewhere in the outer enclosure (see below for discussion of mortuary features).

Field systems

Field systems, probably post-dating the outer settlement, were mapped between the inner fortress and the outer fortification wall, and outside the southern fortification wall fragment (Figure 2). Unsurprisingly, these seem to be situated where local topography minimises erosion and wind exposure and favours water retention and soil development. In a few cases, stone structures appear to abut field boundaries, and may have served as animal pens or small buildings. Furrows are clearly visible in the hillshades, though no evidence for the recent ploughing of these fields was apparent during the ground survey. Field systems are notoriously hard to date, but there are some indications of phasing. The outer settlement may once have extended into areas later covered by these field systems; partially preserved features are noted within the boundaries of several fields (Figure 6). One example shows a circular feature, cut by both an interior, subdividing field boundary and by plough furrows (with a different orientation from the subdivision), suggesting at least three phases of use. The last of these was probably in the Soviet era, based on examination of satellite imagery (KH-9 mission: 1204-4, frame: 39, date: 1 December 1972).

Figure 6. Hillshades of field systems showing plough-damaged features (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Outer settlement

While ground-based observation (Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili2019; Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022) had previously indicated the presence of structures, the extent of the settlement and the number of structures revealed in the aerial survey is unexpected, and has few parallels (Figures 4, 7 & 8). The best-preserved, most visible section of this outer settlement covers an area of 20–25ha between the field systems and the complete outer wall (Figure 4), but the evidence for ploughed-out structures in the field systems hints at an even greater extent. The settlement is bounded by the fortification wall to the west, which encloses a total area of about 56ha, suggesting an upper bound for the settlement area. A 56ha walled settlement (up to 80ha if one includes areas defined by the partial fortification walls), is unusually large for the South Caucasus. Indeed, it approaches or exceeds the areas enclosed by the walls of major medieval towns and cities of the South Caucasus, such as Dmanisi (14ha, just 13km east of Dmanisis Gora) (Kopaliani Reference Kopaliani2017: 235), Tbilisi (65–70ha) (Kvirkvelia Reference Kvirkvelia1985: 17, 33) and even Ani (70–80ha) (Watenpaugh Reference Watenpaugh2014), one of the largest medieval cities of the region.

Figure 7. Comparison of the outer settlement at Dmanisis Gora (left) and a medieval or post-medieval settlement at Kariani, 6km north-east of Dmanisis Gora (right). Scale and hillshade parameters are identical; note differences in topographic prominence and spatial structure of compounds (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Figure 8. Oblique aerial view of outer enclosure from the north-west (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

The structures mapped within the settlement vary considerably but may largely be classed as discrete rectangular or curvilinear stone structures or compounds 15–40m in diameter (Figure 9). Surface exposure and preservation is variable, but the clearest examples are well-built drystone walls two courses wide. Some stone structures may be animal pens or unroofed courtyards. There does not appear to be any systematic variation in building morphology across the outer settlement; more rounded and more rectangular features are observed throughout. Individual compounds do not usually abut one another directly, and there is often open space between them. This low- to medium-density patterning differs from the compact agglomerated room blocks of later settlements in the region (Figure 6) and Iron Age cities elsewhere in the Near East (e.g. Casana & Herrmann Reference Casana and Herrmann2010).

Figure 9. Stone structures in the outer settlement, with transparent grey interpretive overlays, showing structures with walls two stones thick (A & B) examples of both curvilinear and rectilinear structures (B–D) and a structure abutting a fortification wall (E) (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Mortuary activity is attested within the outer settlement, and—as mentioned above—possibly in association with the fortification walls (Figure 10). Several clear cromlechs or low kurgans were identified, with a larger number of possible examples. Suspected cist graves were also noted in the outer settlement, but these smaller burials are more difficult to confirm without excavation. Mortuary features are scattered throughout the outer settlement, without a segregated mortuary zone. The possible association of cromlechs and the 1km fortification wall is intriguing as it potentially mirrors a cist grave found at the gate of the inner fortress (Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022: 316–17).

Figure 10. Surface detail and possible interpretations of mortuary structures in the outer settlement (figure by N. Erb-Satullo).

Outcrops of bedrock within the outer enclosure indicate a shallower depth of sediment than in the inner fortress. Together with the near total absence of surface ceramics, the shallow sedimentation is unusual considering the substantial investment in the built environment shown by the stone architecture and defensive walls (though admittedly, unploughed highland pasture is unfavourable to surface visibility of ceramics). The combination of abundant stone-built architecture and apparent low intensity and/or duration of occupation in this area requires explanation.

Discussion

Chronology

The absence of surface ceramics precludes dating of features identified in the outer enclosure through ceramic typologies. Nonetheless, careful examination of the remains enables some general observations about site chronology. These reconstructions must necessarily be provisional, but useful inferences can be made.

As noted above, there are indications that the field systems, terraces and plough furrows post-date the settlement in the outer enclosure. The presence of partially preserved plough-damaged structures within the field system supports this conclusion. The ruined barn in the field nearest the inner fortress cuts across one of these field boundaries suggesting that the barn is one of the latest structures built on the site, most likely in the nineteenth to mid-twentieth century.

A key question is whether the fortification walls, compounds, graves and smaller structures in the outer settlement were contemporary with the late-second and first-millennia BC occupation in the inner fortress. The settlement is clearly bounded by the outer fortification wall, suggesting that either (a) the wall was built to surround a still-occupied settlement or (b) the settlement was built when the wall could still serve as a protective barrier. Still, even in the latter scenario, a prolonged chronological gap between wall and settlement construction is unlikely, as the structure and topographic expression of large first and second millennium AD settlements are markedly different (Figure 7).

The chronology of the sustained occupation in the inner fortress has bearing on the chronological interpretation of the outer settlement. As noted above, radiocarbon dates and most of the ceramic assemblage reliably dates the occupation in the inner fortress to the late second and first millennia BC. Small quantities of possibly post-Iron Age sherds were occasionally identified in the uppermost layers during the excavation of the inner fortress, but this activity is at present difficult to characterise and there is little indication of a later settlement of any size. Glazed ceramics are a common feature in medieval settlements in the region, but only one definitively non-modern glazed sherd, of unclear date (10mm × 15mm) has been recorded among the >50 000 sherds processed from the 2018, 2023 and 2024 excavations. Furthermore, the proportion of high-fired red and buff sherds (i.e. fabrics that are definitely post-Iron Age) recorded is less than one per cent of the assemblage.

Several lines of reasoning suggest that the outer fortification and settlement were roughly contemporary with the occupation of the inner fortress, forming a single coherent complex. First, the structure and architectural style of the outer fortification walls are comparable to the inner fortification walls; both were constructed of minimally or un-worked boulders with a similar range of sizes assembled without mortar into walls more than 2m thick. Second, the inner fortress and the outer settlement/fortification walls are mutually dependent with respect to defence, so it is implausible that the outer settlement would be occupied when the inner fortress was not. Topography restricts surveillance of approaches to the inner fortress from the west, while the walls of the outer enclosure have excellent westward visibility. Conversely, most of the outer settlement lacks views of the key point of access to the plateau next to the inner fortress, and there are no corresponding eastern defences other than the inner fortress to protect from attacks in that direction. It is probable that a settlement of dozens of hectares would take advantage of the defensive affordances of the inner fortress, and thus leave clear traces of occupation there. The absence of substantial later occupation in the fortress therefore supports a first millennium BC or earlier date for the outer settlement.

Third, cromlech graves are best documented from the second and first millennia BC, so the examples of cromlechs in the outer settlement are also suggestive of a general date in this period. Fourth, medieval and later second millennium AD settlements of this size tend to have churches, many of which are still standing. Finally, it is also improbable that a fortified medieval settlement exceeding the size of the nearby medieval site of Dmanisi (Kopaliani Reference Kopaliani2017) and located in its immediate hinterland would escape mention in historical records. This precludes the possibility of a much later date for the outer settlement.

In the absence of absolute dating of the outer settlement, we cannot categorically rule out other chronological schemes besides our proposed Late Bronze or Iron Age date for the outer fortification and settlement, roughly contemporary with the inner fortress. Our phasing retains significant uncertainty, in the sense that ‘roughly contemporary’ encompasses a range of different possible models of site chronology. However, hypothetical chronologies that differ radically (e.g. that the outer settlement and fortification system is medieval or later) are implausible given the current evidence.

Site structure and fortress-hinterland dynamics

The comparatively thin stratification in the outer settlement suggests a lower intensity or duration of occupation relative to the inner fortress, despite the investment that construction of the outer defensive walls and settlement would have entailed. One possibility is that occupation in the outer settlement was regular enough to warrant these efforts, but short enough to preclude significant archaeological stratification.

Prior research on fortresses and pastoralism in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age offers a potential mechanism and explanation for these observations. It is possible that a segment of the population maintained loose ties with fortified strongpoints that emerged in the Late Bronze Age landscape (Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013; Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Jachvliani, Kalayci, Puturidze and Simon2019). The large outer settlement at Dmanisis Gora may be a manifestation of this phenomenon—a settlement population that expanded and contracted as the mobile segment gathered to, and dispersed from, the fortress.

Dmanisis Gora sits in a transitional zone, where the plateau widens as it leaves the narrow, forested foothill gorges, and where modern arable land transitions into pastureland (Figure 1). Dozens of modern and recent historic seasonal pastoral campsites dot the Javakheti Range to the east, and Dmanisis Gora lies directly on the route to the lowlands. Bearing in mind all the caveats of projecting an environmental and ethnographic present into the past (see Arbuckle & Hammer Reference Arbuckle and Hammer2019), one possibility is that Dmanisis Gora served as a staging ground for pastoral groups during transitional periods in the spring and autumn. Isotopic evidence for seasonal transhumance in the Bronze and Iron Age is somewhat equivocal (Chazin et al. Reference Chazin, Gordon and Knudson2019; Nugent Reference Nugent2020). However, other lines of evidence suggest the persistence of mobile pastoralist lifeways among segments of the population in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age (Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013) and recent obsidian sourcing research implies the existence of structured networks of lowland-highland interaction in areas around Dmanisis Gora (Erb-Satullo et al. Reference Erb-Satullo, Rutter, Frahm, Jachvliani, Albert and Smith2023).

On the other hand, the outer settlement might reflect an unsuccessful, short-lived attempt to settle a large population. This scenario does not necessarily exclude a settlement growth model defined by the entrainment of mobile pastoralists and seasonal fluctuations related to the movement of people between summer and winter pasture. The large defensive walls and stone-built compounds may have aimed to entice populations into more regular or permanent cohabitation with those residing permanently in the inner fortress. The character of interactions between these permanent residents in the inner fortress and (potentially seasonal) residents of the outer settlement remains unclear. There are indications that fortresses were spaces of ritual activity and economic production (Erb-Satullo & Jachvliani Reference Erb-Satullo and Jachvliani2022), which are sometimes linked with a trend of emerging sovereignty and political authority (Smith & Leon Reference Smith and Leon2014). However, evidence for a political or administrative apparatus within these fortresses capable of exercising coercive authority is limited in comparison with Late Bronze Age Hittite and Iron Age Urartian fortresses. Indeed, the protection afforded by gathering around well-defended strongholds, especially ones large enough to encompass both people and animals, may have been more attractive than coercive, especially if such arrangements were more temporary.

The overall size of Dmanisis Gora considerably exceeds that of nearby fortresses mapped in the wider survey, and the inner fortress is defended by a double rather than a single wall, features that might suggest a level of primacy or influence over the immediate hinterland (Figure 1). On the other hand, the area of the inner fortress (1.5ha) is not orders of magnitude larger than other fortresses with a 10km radius (0.5–0.75ha). Moreover, in the wider regional context of fortresses in southern Georgia (cf. Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili2019), Dmanisis Gora's inner fortress is largely comparable in size to cyclopean fortresses elsewhere, including those where large outer enclosures have not been documented. While sparse data on lower settlements do not permit a robust region-wide quantitative assessment, in this instance, size of the fortress core does not seem to scale proportionally with the size of the outer settlement. If the size of the inner fortress can be viewed as a rough proxy for its administrative capabilities, storage facilities and/or capacity for coercive authority, the pattern might suggest that the apparatus of authority did not grow in proportion to the size of the settlement. This might be consistent with a scenario of fluctuating lower-intensity occupation in the outer settlement and might support models of population aggregation that were more communal than coercive.

To be clear, the various models discussed here posit relationships between people residing in the outer settlement and those in the fortress core that are dependent on plausible but unconfirmed assumptions of rough contemporaneity of occupation. Whatever the precise chronology of occupation, Dmanisis Gora provides further definition to a type of site whose characteristics—due to preservation and/or patterns of research—have proven difficult to assess. For example, Oğlanqala-Qızqala (Naxçıvan, Azerbaijan) has what may be a large 300–400ha enclosure, but the wall is only partly preserved and, as at Dmanisis Gora, it is dated indirectly by its articulation with a pair of Early/Middle Iron Age fortresses (Herrmann & Hammer Reference Herrmann and Hammer2019). Despite excavation, geophysical survey and systematic surface survey, the spatial extent of settlement within the enclosure remains unclear, primarily due to sedimentation and damage from intensive modern agriculture. Other potential large sites lack systematic survey (UAV mapping, surface collection or geophysics) which would enable detailed assessment. These examples suggest that the Dmanisis Gora mega-fortress, while exceptional in size and preservation, is not entirely without parallel.

Conclusion

High-resolution UAV-based aerial survey of Dmanisis Gora reveals the extent of the large outer fortification system and settlement, which has few documented parallels in the region. If the occupation of the inner fortress and outer settlement were roughly contemporary, as we suggest, this settlement would be one of the largest known in the South Caucasus Late Bronze and Iron Age. Yet the mismatch between the substantial investment in stone architecture on the one hand, and the thinness of archaeological deposition and the rarity of surface finds on the other, suggests a form of settlement where both the density and intensity of occupation was low. The data from Dmanisis Gora may therefore support theories about the continuing importance of pastoral mobility in Late Bronze and Early Iron Age societies (Lindsay & Greene Reference Lindsay and Greene2013) through a model of low-intensity or intermittent occupation, though more robust evidence regarding site chronology and occupation intensity is needed.

Lastly, while it remains unclear to what extent the twelfth-century BC ‘Bronze Age Collapse’ impacted the South Caucasus, material culture and settlement patterns in this region show remarkable continuity across the Bronze Age–Iron Age transition, suggesting a possible link between settlement dynamics and societal resilience. This trajectory appears to be in sharp contrast to the rest of the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean. A complete assessment, however, requires both more systematic survey of other potentially similar sites and more intensive investigation of Dmanisis Gora itself.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lara Fabian and Tiffany Earley-Spadoni, who provided in-press manuscripts of their upcoming work, as well as Kakha Kakhiani and Zurab Makharadze, who provided support and encouragement for field research at Dmanisis Gora.

Funding statement

Support for the project came from the Gerald Averay Wainwright Fund, the British Institute at Ankara (BIAA) and a Gerda Henkel Foundation Project Grant (AZ 33/F/22).