Introduction

One of the central problems of archaeology is determining what we know and what we do not. What we know seems to increase exponentially year on year, month on month; we are working in a moment of big data and burgeoning scientific discovery. Kristiansen (Reference Kristiansen2014) terms this a ‘third science revolution’ which he sees as pushing archaeologists past the realm of speculative inference towards deductive methods for finding absolute knowledge, truth-with-a-capital-T (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen2022a: 1–5). Some find in this newly constituted scientific archaeology the death knell of theory; others just want more data to narrow down the possibilities we navigate in studying the past (Johannsen et al. Reference Johannsen, Larson, Meltzer and Vander Linden2017; Racimo et al. Reference Racimo, Sikora, Linden, Schroeder and Lalueza-Fox2020; among critiques of this see e.g. Sørensen Reference Sørensen2016: 746).

Ribeiro (Reference Ribeiro2022) sees in this retreat to data an epistemological poverty yielding an unrepresentative, singular discourse about past lifeways. The Black Trowel Collective (2023) calls on us to resist the singular, grand narratives and totalising chronopolitics that deny the multiplicity of past people's creativity and meticulously separate unchanging past from inevitable future. Immutable pasts, they remind us, reinforce our own status quo, inhibiting activism and calls for radical change. Responding to this call to arms, I offer a different path through the forest of big data, one that wends with the possibility inherent in complex pasts and the capacity of archaeological narratives to enrich our imaginaries and embolden us to work towards a better future.

My point of departure is that archaeological data are unruly. We can survey the ground, survey the archives and survey the memories of descendent populations, but we cannot make the chthonic world conform. Whether we study subsurface features, standing buildings or collections of archaeological materials, we inevitably find ourselves braving the unexpected, outside of our comfort zones, teetering on the precipice between error and insight.

This unruliness makes every encounter with the past uncanny; not only is it a wildly, perhaps confrontingly, unfamiliar place, but our data themselves are unsettlingly strange, verging on transgressive (Buchli & Lucas Reference Buchli and Lucas2001; Graves-Brown Reference Graves-Brown2011). Faced with this disorder, a retreat to data and simple narratives might seem justified.

But mess has power. Following Murney's (Reference Murney2023) anarcho-feminist approach, joyful, riotous, unruly mess creates unplanned constellations and unexpected solidarity among marginalised people and things. Mess is inimical to control. Uncontrolled, disordered archaeological data create turbulence in historical narratives and disrupt expectations of both the past and the future (Olsen Reference Olsen2012: 25), opening messy spaces to reimagine the past worlds we construct (cf. Wylie Reference Wylie2002: 191) and the futures we might imagine (Black Trowel Collective 2023).

In this article, I build outwards from feminist scholarship within and beyond archaeology to think through the implications of embracing this messy unruliness for our discipline, our practice and our ability to tell new sorts of pasts to reshape the world. My narrative is intentionally curvilinear, both in response to Pluciennik's (Reference Pluciennik1999) call to find other ways of telling that make evident the complex textures of a messy past, and in homage to my feminist archaeologist foremothers who radically reframed archaeological sites and objects through the judicious application of experimental writing (e.g. Spector Reference Spector1993; Tringham Reference Tringham, Clarke, Frederick and Brown2015).

Feminist futures for uncertain pasts

Feminist scholarship works to expose submerged patterns of power and domination, to create friction around the smooth glide of the status quo and to articulate counter-narratives that challenge established authorities, scholarly canons and easy common wisdom. To do so, we must first interrogate the sources of domination within our various domains of research and stake out generative positions from which to narrate (Haraway Reference Haraway1988). Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2006) advocates a slantwise approach to our objects of study to disorient ourselves within an otherwise familiar world and make visible the queer, the disempowered and the hidden. Schuster (Reference Schuster2021) argues that, to observe the daily articulations and embodied experiences of power and capital, we must turn away from the well-tilled core to the wild, weedy margins (see also Tsing Reference Tsing2012; Haraway Reference Haraway2016). The new shoots of alternative social orders and subversive articulations of power, gender and community flourish among ruins as well as in unnoticed quarters of our central places (Tsing Reference Tsing2015). The point is not to manifest feminised margins, leaving masculine cores undisrupted (Freeman Reference Freeman2001) but to uncover the liminal, overgrown and overlooked interstices of daily life, wherever they are located. Here, a complex and generative ambiguity takes root and offers us a position of resistance against the certitude of the status quo.

Feminist archaeology recognises the construction of past worlds as a social practice with the power to transform the present as much as the past. Early feminist archaeologies opened the domestic up to critical analysis, creating new knowledge by tracing the economic, political and social power that flowed through feminised spheres, often through women's hands (e.g. papers in Conkey & Gero Reference Conkey and Gero1991; du Cros & Smith Reference du Cros and Smith1993). This work seeded a wildflower meadow of activist, gendered and queer archaeologies that continue to blossom well beyond traditionally feminised bodies and spaces (e.g. Ghisleni et al. Reference Ghisleni, Jordan and Fioccoprile2016; Moen Reference Moen2019).

Feminist epistemologies also recognise the multiplicity of expertise, the fragmentation of knowledge and the nature of situated understanding needed to navigate an unruly, fragmented and contradictory past (Gero Reference Gero2007; Wylie Reference Wylie2007). Moreover, thanks to feminism's imperative to act—to turn critical writing into radical action—feminist archaeology has staked out a unique middle ground between interpretation and empiricism: the narratives we write from the detritus of the past are contingent and constructed, but they must also speak directly to the material conditions of the world around us (Wylie Reference Wylie1997; Conkey Reference Conkey2003: 874).

A life in ruins

The material basis of our field lies in the fragmented remains of things, structures, creatures, landscapes and bodies. These data are not just incomplete but irreparably broken; we do not know what is not represented, in most cases we cannot and will never know. Indeed, social action is both polysemic and vague, comprising overlapping fuzzy constellations; so even if our data were, on some level, intact, they would remain porous and partial (Sørensen Reference Sørensen2016). We are Victor Frankenstein assembling parts in monstrous harmony and our work is haunted by “absent presences” (Lucas Reference Lucas2012: 14–16).

This has led to sustained concern that our field is underdetermined (Turner Reference Turner2005, Reference Turner2007; Chapman & Wylie Reference Chapman and Wylie2016: 15–31; Perreault Reference Perreault2019) and our data gappy (Currie Reference Currie2018), meaning we lack enough complete data to draw incontrovertible inferences about the worlds of past people, their societies and their value systems. This work sees the holes in the assemblage of archaeological materials as traps into which we fall as we try valiantly to perceive the truth of the past in our eccentric data (although, see Currie Reference Currie2021).

But archaeologists are rather adept at understanding holes. We are magpies (Frieman Reference Frieman2021: 3) or methodological omnivores (Currie Reference Currie2015) who persevere in taping together fragments (both newly collected and retained within legacy collections), cobbling together analytical methods drawn from this field and that field, and bundling the whole mess up into carefully braided narratives that give us a flicker of insight into how some people living at various times in the past might have understood the world they inhabited and the things with which they came into contact. Gero (Reference Gero2007) sees this sort of flexible narrative building as a powerful tool to navigate the underdetermination and indeterminacy of the archaeological past and one that is primed to do feminist work.

Put otherwise, we weave tapestries from the strings of the past but the patterns emerge from our imagination not the strings themselves, which, of course, we have spun ourselves as well, twining sturdy strands from otherwise disconnected fibres. These patterns then are not fixed or real, but chosen carefully and they sometimes flow around, sometimes cover up and sometimes incorporate all the things we do not know. We can choose to sew up the frayed edges or we might embroider around them, making them visible and part of the work.

Mobility as possibility

Here, I present an example of how I embrace the unknown in my own research. This centres on the mobility narratives emerging from isotopic and ancient DNA literature, their shaky material and interpretative foundations and the routes through the data I have found by looking for the gaps.

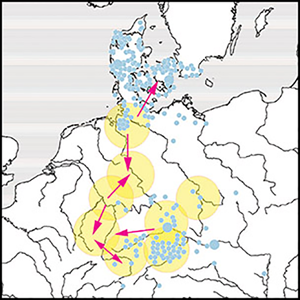

Until recently, our tools for assessing individual mobility have been relatively blunt. We were forced to make a set of nested assumptions: first that specific objects (sometimes found in or with burials, sometimes not) could be associated with a social category (i.e. gender and status); and, second, that identifying points of origin (either of raw material or of style) for these objects should give us insight into the mobility of people. Thus, archaeologists chart the find locations of different types of objects in order to model the human connectivity they represented and to divine insights into social structure. So, a map contrasting the find locations of a specific Bronze Age sword type and the origin of Bronze Age ornament sets recovered in Denmark (Figure 1) becomes gendered patterns of movement. Men (with swords) travelled and returned home with wives (who wore ornaments). And masculine dominance is extrapolated into chiefdoms (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Fernández-Götz, Nimura, Stockhammer and Cartwright2022b).

Figure 1. A model of binary gendered mobility during the Middle Bronze Age (redrawn after Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005: fig. 117).

These narratives become phorophytes for new scientific data and root themselves deeper by the association. Add DNA to swords and this is how the Bronze Age world definitively looked:

Kinship structure … was based on a dominant male line that married in women from other groups and married out their own daughters in this way building up a network of alliances, which could become part of a competitive mobilization in periods of unrest, and perhaps also to secure access to resources like metal (Sjögren et al. Reference Sjögren2020: 23).

It is my position that this reductive gender binary reproduces outdated ethnography, embedding into our archaeological narratives sexist assumptions, including female passivity, cisheteronormativity and an unquestioned and untextured patriarchal domination (Frieman et al. Reference Frieman, Teather and Morgan2019). It also assumes anachronistic paradigms of mobility, its experience by individuals of different gender, status and identity, and its association with power and freedom when experienced without friction (Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Frieman, Furholt, Burmeister and Johannsenin press).

Archaeological data, as idiosyncratic and fragmented as I described them above, can be mobilised to challenge these bland Boys’ Own Adventures, but that depends entirely on how these data are deployed. To demonstrate this, I want to look at a specific example where what we know, what we do not know and what we choose to assume have enormous consequences for interpretation.

Around the middle of the fourteenth century BC, a funeral took place in what is now Egtved, Jutland. A young person had died and was elaborately laid to rest (Thomsen Reference Thomsen1929; Holst et al. Reference Holst, Breuning-Madsen and Rasmussen2001; Randsborg & Christensen Reference Randsborg and Christensen2006). They were dressed in a special outfit made from wool ornamented with bronze, jewellery, and a net for their short, blond hair (Figure 2). Various special objects were interred with them, including the cremated bones of a child. They were wrapped in an oxhide, placed in an oak coffin and a mound was erected over them. Because of the process of mound building, the interior was anaerobically preserved, meaning many of the organic materials remain, including hair, fingernails and tooth enamel. Frei and colleagues’ (Reference Frei2015) isotopic analysis reveals that the decedent was travelling regularly and repeatedly in the last few months of life. They identified this young person as a woman, likely a foreign bride.

Figure 2. ‘Egtvedpigen’ (Egtved Girl) sketch by Gustav Rosenberg, 1924 (reproduced with permission of the National Museum of Denmark Archives).

But here is where the possibility lies: the corded skirt in which they were interred may have been worn by female ritual specialists (at least in the later Bronze Age) (Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant2014); so, one reading of the Egtved adolescent's highly mobile lifestyle could be that they were engaged in a sort of cosmologically driven, long-distance mobility that current models restrict to Bronze Age men (e.g. Kristiansen & Larsson Reference Kristiansen and Larsson2005). Alternatively, or perhaps concomitantly, this individual may have been travelling alongside textiles, yarn or fleeces, a hypothesis that is particularly relevant as their own clothing was woven from the wool of sheep that were foreign to Denmark (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Berghe and Kristiansen2017). Wool as much as bronze drove the connectivity of the Bronze Age world, and sheep were important community members (Armstrong Oma Reference Armstrong Oma2018; Sabatini & Bergerbrant Reference Sabatini and Bergerbrant2020). Was the decedent a shepherd? A weaver? A wool broker? A translator? Did they have kin connections that eased the back-and-forth flow of wool? Were the sheep their kin?

Their sex is unknown: no diagnostic bones are preserved, and DNA analysis failed. Were they female? Were they a woman? Although previously undisputed, here uncertainty creates space to think about more expansive gender systems and the role of gendering in funerary rites. Was the burial in a very local outfit and the association with a small child an attempt to control, domesticate or feminise a body that did not conform to local gender practices, perhaps due to their way of moving in the world (Frieman et al. Reference Frieman, Teather and Morgan2019)?

Were they travelling to nurse a cousin, a parent, an aunt? To bring a beloved child home for burial? What were the nature of their ties to the community who buried them—evidently their death and funeral were significant rites, was it through care that they became kin?

Were they local or foreign? Kin or stranger? Would a stranger merit such a burial? Can kin be foreign?

As soon as we map out our unknowns, a thousand new stories emerge, each ready for critical analysis and each with a different resonance in our present.

Unproof and ambiguity

In Ursula K. Le Guin's famous science fiction novel The Left Hand of Darkness (Reference Le Guin1969), the outside observer, Genry, witnesses a religious event in which the future is accurately foretold. The religious leader, Faxe, scoffs at Genry's wonder:

The unknown, … the unforetold, the unproven, that is what life is based on. Ignorance is the ground of thought. Unproof is the ground of action. If it were proven that there is no God there would be no religion … But also if it were proven that there is a God, there would be no religion … The only thing that makes life possible is permanent, intolerable uncertainty: not knowing what comes next (Le Guin Reference Le Guin1969: 65–66).

Here, I advocate for an archaeology of unproof. The unproof of archaeology encompasses the holes in our data, the ambiguity of our results, those things that are unknown and overlooked or unknown and deemed unknowable. These are the grounds of our action. Unproof is ever-present in our assemblages, our methods, the unravelling skeins of our narratives; but we pay only intermittent attention to it. Gero (Reference Gero2007) has already explained that creating unwarranted certitude also creates worse archaeological outcomes; but I would build on her work to suggest that, in choosing to smooth over the uncertainty as intolerable and despair at its permanence, we lose the most powerful part of our material.

This is my feminist intervention into archaeological methods: we must accentuate how the unproof entangles with the data.

The most exciting archaeological finds are those we do not know to expect—the village preserved in mud, the body in the glacier, the seven-generation genetic pedigree. The wonder in these finds emerges from the juxtaposition of new methods and data with common wisdom and accepted fact. They backlight unproof, which, in turn, contextualises the new find and expands the scope of its possible significance.

Unproof also reveals new interpretative spaces in our data. We are ontologically distant to the past people we study—our wildest imagining will not and cannot accurately reproduce their perceptions of reality. We can, however, find extraordinary power in the unknown, the unforetold and the unproven.

First, because it makes us question our own status quo, the things we think are commonsense, normal, expected. It helps us trace the flows of power and what those flows conceal.

Second, because it forces us to acknowledge the variety of lived experiences in the past; the people who never wrote or were rarely written about but who raised children, sang songs, invented technologies, sewed clothes and cared for animals. Archaeology's interest in these historically invisible peoples and practices militates against elite-focused models of singular geniuses, sequences of kings and entrepreneurial movers and shakers (Frieman Reference Frieman2021). Unproof creates space for resistance against regimes of domination.

Third, because it gives us material to prefigure alternate social conformations and a better future (Borck Reference Borck2019). If we can model a (past) world otherwise, with different constellations of identity, value structures and forms of relation, we can use that to critique contemporary inequalities. Moreover, we can project those radically distant and different conformations into the future to imagine paths to a better, more equitable and freer world (Politopoulos et al. Reference Politopoulos, Frieman, Flexner and Borck2024).

Attending to unproof requires us to navigate the holes in our data and embrace the unknown. This in turn gives us scope for possibility, for creativity and for action. We must become mediators between the multiplicity of fluid pasts and the potentiality of better futures. But this radical reorientation entails, fundamentally, only a slight shift in practice to make explicit the method of implicit disciplinary knowledge, because, as any archaeologist who has ever held a spade will tell you, faced with a new project, site or data set, not knowing is inevitably what comes next.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Caroline Schuster, Matt Walsh, Simon Coxe and the Black Trowel Collective.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Debate responses

Antiquity invited four authors to respond to this Debate article; with a final response from the original authors.

Encounters with otherness and uncertainty: a response to Frieman by Tim Flohr Sørensen https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.126

Historical leftovers, racialised Others and the coloniality of archaeology: a response to Frieman by Beatriz Marín-Aguilera https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.152

From proof and unproof to critical fabulation: a response to Frieman by Rachel J. Crellin https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.150

Describing the ineffable: a response to Frieman by James G. Gibb https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.125

Unproofing expectations: confronting partial pasts and futures by Catherine J. Frieman https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.172